Abstract

This article describes the life circumstances and risk behaviors of 552 adolescent males returning home from jail. Most young men reported several sources of support in their lives and many had more tolerant views toward women and intimate relationships than portrayed in mainstream media. They also reported high levels of marijuana and alcohol use, risky sexual behavior, and prior arrests. Investigators designed the Returning Educated African American and Latino Men to Enriched Neighborhoods (REAL MEN) program, a jail and community program to reduce drug use, HIV risk, and rearrest. By helping participants examine alternative paths to manhood and consider racial/ethnic pride as a source of strength, REAL MEN addressed the assets of these young men as well as their challenges. Our findings suggest that interventions that emphasize the assets of these young men may be better able to engage them than programs that seek to impose adult values.

Keywords: jail, adolescent, masculinity, racial/ethnic pride, reentry, HIV, African American, Latino

In 2004, an estimated 800,000 young people under the age of 20 spent time in correctional or juvenile justice facilities in the United States, a number that has increased dramatically in recent decades, which gives this country the highest rate of youth incarceration in the developed world (Harrison & Beck, 2006). For some youth, incarceration is a single experience with limited consequences but for most it is the starting point for ongoing criminal justice system contact. As incarceration is associated with a disproportionate burden of infectious and chronic diseases, substance abuse, mental health problems, violence, unemployment, school dropout, and discrimination (Freudenberg, 2001; National Commission on Correctional Health Care [NCCHC], 2002; Reentry Policy Council, 2005), finding ways to help incarcerated youth improve their lives and avoid reincarceration is an important health goal. In this article, we describe the health and social characteristics of a sample of 552 adolescent males incarcerated in New York City (NYC) jails and an intervention designed to reduce their risk of HIV infection, substance use, and rearrest. Our broader goal is to inform the development of programs and policies that can reduce the health and social consequences of adolescent incarceration.

Adolescents are incarcerated in juvenile justice facilities, jails, or prisons. In the 1980s and the 1990s, the number of inmates under 18 years of age held in state prisons and jails in the United States doubled (Strom, 2000). More recently, these rates of growth have slowed somewhat (Harrison & Beck, 2006). In 2004, an estimated 125,000 youth under the age of 18 were admitted to U.S. jails (Beck, 2006; Harrison & Beck, 2006). Accounting for multiple admissions, this represents 89,000 unique individuals. In addition, at least 600,000 18- and 19-year-olds were admitted to U.S. jails. Another 100,000 teens were admitted to juvenile justice facilities that year (Sickmund, Sladky, & Kang, 2005). These youth were overwhelmingly African American or Latino, and almost all are male and economically impoverished, ensuring that the impact of incarceration would have disproportionate effects by race, gender, and class.

The vast majority of incarcerated adolescents return to their communities within days, weeks, or months. Studies show that between half and three quarters of adolescent offenders are rearrested in the year after release (Fagan, 1996; Freudenberg, Daniels, Crum, Perkins, & Richie, 2005). This “churning” (Taxman, Byrne, & Pattavina, 2005) between detention and neighborhoods disrupts individuals, families, and communities. For the individual, it leads to school failure or dropout and reduced employment prospects (Holzer, Offner, & Sorenson, 2005). For families, it contributes to increased family conflict, economic dependence, or housing eviction (Travis, Soloman, & Waul, 2005). For communities, it increases crime (Clear, Rose, Waring, & Scully, 2003) and reduces community cohesion, associated with increases in violence and infectious diseases (Cohen et al., 2000; Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997). For municipalities, high rates of recidivism contribute to spiraling criminal justice costs (annual incarceration costs for adolescents can reach US$100,000 per year, per adolescent) and reduced resources for education and health care (Reentry Policy Council, 2005). Finally, youth reentry is complicated by pervasive negative attitudes toward young Black and Latino men, attitudes often shaped by mass media, politicians, and researchers (Bennett, DiIulio, & Walters, 1996; Hutchinson, 1997).

Researchers have consistently shown that adolescents who have been incarcerated are more likely to experience injuries because of violence and to engage in substance use and sexual behaviors that place them at increased risk for HIV/AIDS (Castrucci & Martin, 2002; Crosby, DiClemente, Wingood, Rose, & Levine, 2003; Morris et al., 1995; Teplin, Mericle, McClelland, & Abram, 2003), compared to nonincarcerated counterparts. Some researchers have found that adolescents involved in criminal justice are more likely to report ever having had sex, have more partners, ever had a sexually transmitted infection, use drugs or alcohol during sex (Crosby et al., 2003; DiClemente, Lanier, Horan, & Lodico, 1991), and are more likely to have experienced physical injuries, including gunshot wounds (Forrest, Tambor, Riley, Ensminger, & Starfield, 2000). Given the disproportionate impact of incarceration on the health of young men of color from economically disadvantaged urban neighborhoods, we sought to develop an intervention that addressed the context of this disparity. We identified gender and race as significant factors that shape the experiences of young urban men.

Gender, specifically masculinity, is strongly linked to criminal justice involvement. Evidence shows that young men are overwhelmingly more likely to be arrested and rearrested than are young women of the same age, racial/ethnic group, or neighborhood suggesting that gender is an important contributing factor leading to incarceration (Messerschmidt, 1997, 2000; Miller, 1996). Some young people from urban neighborhoods with concentrated poverty may come to regard as normative expressions of masculinity that include having multiple sex partners, exercising control over women either through intimidation or force, and involvement in the drug trade, along with the attendant use of violence and weapons in the street in defense of respect (Anderson, 2000; Bourgois, 1995; Mullings, 2001; Whitehead, Peterson, & Kaljee, 1994). These practices associated with masculinity emerge in neighborhoods that are among the most economically impoverished and that are increasingly intertwined with the criminal justice system, leading to what one scholar has called a “deadly symbiosis” between neighborhoods and jails (Wacquant, 2001). Some scholars have labeled this normative context and set of practices as “hypermasculine” behavior that contributes to HIV risk (Wolfe, 2003), yet other scholars have challenged this notion and assert that there are multiple dimensions to masculinity for young, street-life oriented men of color (Payne, 2006). Our previous research (Freudenberg et al., 2005), pilot data collected through focus groups with young men leaving jail, and the existing literature (Wingood & DiClemente, 1992) suggest that engaging people leaving jail in considering the gender and normative (yet destructive) expectations about masculinity can provide an effective opportunity for intervention. At the time we developed the intervention, there was only very limited research that addressed gender and that with young African American girls. Since that time, additional literature has emerged that points to interventions with young men of color that challenge practices associated with masculinity in ways that diminish some harmful outcomes (Aronson, Whitehead, & Baber, 2003; Russell, Alexander, & Corbo, 2000). In addition to gender, we identified race as an important factor that not only shapes the experience of incarcerated young men of color but also offers opportunities for intervention.

Evidence from a number of disciplines suggests that the lives of African Americans and Hispanics in the United States are negatively affected by both structural and individual racism (Feagin & Sykes, 1993; Krieger, Smith, Naishadham, Hartman, & Barbeau, 2005; Salvatore & Shelton, 2007; Zamudio & Rios, 2006) manifested in the environment (Liam, 2006), and through key institutions such as housing (Massey & Denton, 1993; Squires & Kubrin, 2006), education (Ferguson, 2000; Mateu-Gelabert & Lune, 2007), and employment (Holzer et al., 2005), discrimination that is compounded by the mark of a criminal record (Pager, 2003). In addition, many researchers have demonstrated the damage that racial and economic inequality can have on health (Williams & Collins, 1995). Yet, in the face of such pervasive and harmful hostility, a small but growing body of literature suggests that racial and ethnic pride (Phinney, 1992; Smith, Walker, Fields, Brookins, & Seay, 1999) may be a source of resilience that may protect mental health (Mossakowski, 2003), reduce school dropout (Oyserman, Bybee, & Terry, 2003), substance use (Kulis, Napoli, & Marsiglia, 2002; Marsiglia & Waller, 2002), and HIV-risk behaviors (Russell et al., 2000; Wingood & DiClemente, 1992).

Our previous research, as well as pilot studies for this research, suggests that reentry is a time of heightened vulnerability to risks to health as well as an especially powerful time to offer an intervention because people leaving jail express a strong desire toward positive changes as they transition into the community (Freudenberg et al., 2005). The success of this transition may depend, however, on support for education, work, and avoiding reincarceration. Thus, finding ways to help adolescents returning from jail make a successful transition to their communities and simultaneously reducing risk behaviors in the context of what it means to be a young man of color in a poor urban environment is an urgent social and health priority. To be effective, such interventions must address the youth’s life circumstances and take into account findings from prior evaluation studies. In this study, we focus our attention on understanding (a) the role of masculinity in shaping risk and protective health behaviors, (b) the changing perceptions of young men as they move between jail and community, (c) the assets and barriers within these young men’s lives that influence their reentry outcomes, and (d) the influence of negative media images of incarcerated young men on the public and on those returning from incarceration.

BACKGROUND

REAL MEN, an acronym for Returning Educated African American and Latino Men to Enriched Neighborhoods, was designed to reduce HIV risk, substance use, and recidivism for incarcerated young men in NYC. Participants were recruited from two facilities located at the NYC Department of Correction’s Rikers Island Detention Center that house all male adolescent inmates. In New York state, youth aged 16 and above are sent to adult jails, whereas those under 16 enter the juvenile justice system. During the time participants were recruited for this study, on any given day, more than 1,700 adolescent males aged 16–18 were incarcerated in NYC jails.

Participants were recruited in the jail and completed an informed consent process approved by the Hunter College and NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Institutional Review Boards. Males between the ages of 16 and 18; individuals determined to be eligible for release within 12 months of intake; and those planning to return to the Bronx, Brooklyn, or Manhattan, the boroughs with the highest incarceration rates, were eligible for enrollment. Individuals with psychiatric conditions that would preclude participation in a group intervention were excluded. All participants were volunteers who received no special legal considerations for enrollment. In general, the sample resembled the overall adolescent population leaving NYC jails on racial/ethnic and criminal justice characteristics.

Intake interviews were conducted in the jail by project staff and included questions on demographic, education and employment histories, criminal justice involvement, health, substance use, HIV knowledge, sexual behavior, and attitudes about racial/ethnic identity and gender norms. After the interview, participants were randomly assigned to receive a single jail-based discharge planning session or a 30-hr intervention that began in jail and continued in the community after release.

Demographic Characteristics and Life Circumstances

The mean age of the 552 young men who completed the intake interview between 2002 and 2005, when enrollment ended, was 18 years. More than half (54%) described themselves as Black/non-Hispanics and 37% as Hispanic/Latinos. About 12% were born outside the mainland United States. At arrest, three quarters of participants were residing with their parents or legal guardians and 36% had not yet completed 10th grade. Most young men had substantial prior involvement with the justice system. The mean age at first arrest was 14.8 years. Charges for the most recent arrest were violence related for 37%, drug related for 29%, parole or probation violations for 17%, and property related for 9%. On average, these young men had 5.2 prior arrests; only 9% had no prior arrests.

Many of these young men had encountered difficult life circumstances. Almost half (47%) had been left back in school at least once, 37% had been robbed or mugged, 30% had spent at least 6 months in jail, 13% had been physically or sexually abused, and 8% had been admitted to a mental hospital. More than three quarters had experienced at least one of these difficulties, and 41% reported two or more.

Many participants also had people and institutions to turn to for help. Almost all (96%) had a family member or friend to talk to in times of need, and 70% had someone who encouraged them to reduce drug use. Although the majority of these young men were disconnected from school and work, at the time of arrest, a third were attending school most of the time and 22% were working. A quarter reported a strong sense of racial and ethnic pride, as measured using the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM) scale (Phinney, 1992). Most (88%) reported two or more such sources of support.

Health and Mental Health

For adolescents, these young men showed high rates of medical problems. In the year prior to arrest, 40% had visited a hospital emergency room, 23% had been admitted to a hospital, 16% reported a violence-related injury that required medical care, and 10% reported a current chronic health problem that interfered with daily life. Prevalent health problems in the past year were asthma (reported by 18%), dental problems (24%), and sexually transmitted infections (4%). Young men also reported high rates of psychological and behavioral problems. Nearly a quarter (22%) reported a prior diagnosis of a learning problem. In the year prior to arrest, 13% reported depression and 8% reported serious suicide thoughts or attempts, but only 20% reported any contact with a mental health provider.

Substance Use

These young men reported heavy use of marijuana and alcohol and relatively low rates of use of drugs such as heroin and cocaine, as shown in Table 1. Half reported daily use of marijuana, and almost a third (31%) reported having been drunk on 12 or more days during the past month. Almost half (48%) were daily smokers, a rate much higher than among nonincarcerated adolescents. Using items based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., DSM-IV) diagnostic criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), 20% of participants were identified as drug dependent and 8% as alcohol dependent. Only 19% of young men had participated in drug treatment programs and only 3% had received drug treatment while incarcerated. Among recent drug and alcohol users, 56% had sold drugs to get money for their own use and 10% had engaged in other illegal activities for this purpose.

TABLE 1.

Substance Use Prior to Incarceration

| Percentage | N | |

|---|---|---|

| Marijuana use | ||

| Report ever using marijuana | 82 | 452/552a |

| Recent marijuana use (30 days prior to incarceration) | ||

| None (0 days) | 26 | 146/552 |

| Infrequent use (<10 days) | 11 | 62/552 |

| Frequent use (10–29 days) | 8 | 42/552 |

| Daily users | 55 | 302/552 |

| Alcohol use | ||

| Report ever using alcohol | 65 | 359/552 |

| Recent alcohol use (per week, 30 days prior to incarceration) | ||

| None (0 times per week) | 52 | 283/550 |

| Occasional (1–3 times per week) | 35 | 193/550 |

| Frequent (4–6 times per week) | 6 | 31/550 |

| Daily (7 or more times per week) | 8 | 43/55 |

| Among recent drinkers, times drunk in the past 90 days | 267 | |

| None | 14 | 38/263 |

| 1–11 drunk occasions | 46 | 120/263 |

| 12 or more drunk occasions | 31 | 81/263 |

| Cannot recall number of drunk occasions | 9 | 24/263 |

| Other drug use | ||

| Used hard drugsb (30 days prior to incarceration) | 7 | 36/550 |

| Ever injected drugs with needle | <1 | 1/552 |

| Report ever smoking cigarettes | 62 | 344/552 |

| Daily smoker | 48 | 263/551 |

| One pack or more a day | 17 | 91/541 |

| Daily substance use (30 days prior to incarceration) | ||

| Used marijuana, alcohol, or cigarettes on a daily basis | 70 | 387/550 |

| Drug and alcohol dependencec | ||

| Drug dependent | 20 | 108/552 |

| Alcohol dependent | 8 | 44/552 |

| Ever overdosed on drugs | 3 | 17/552 |

| Substance abuse treatment | ||

| Have received treatment for alcohol or drug abuse (ever) | 19 | 104/552 |

| Among treated, has ever received treatment in a correctional facility | 14 | 15/104 |

| Sources of money for drug and alcohol use/30 days prior to incarceration among recent users | 450 | |

| Sold drugs to get money for drugs or alcohol | 56 | 243/434 |

| Engaged in other illegal activity to get money for drugs/alcohol | 10 | 41/433 |

Base sizes vary slightly due to nonresponse, which has been ignored unless it exceeds 4%.

Includes cocaine/crack, heroin, inhalants, acid, ecstasy, speed, phencyclidine (PCP), steroids, and others.

Dependence defined as saying “yes” to at least 3 of 6 diagnostic criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV).

Sexual Behavior and Gender Attitudes

Young men reported sexual behavior associated with higher risk of unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections including HIV, as shown in Table 2. Average age for onset of sexual intercourse was 13, and the majority (54%) reported both long-term partners, defined as lasting more than 3 months, and short-term partners in the prior year. Forty-three percent reported three or more sexual partners in the 3 months prior to incarceration. Condom use varied considerably between long- and short-term partners. Although 60% reported always using condoms recently with short-term partners, only 31% reported this use with long-term partners.

TABLE 2.

Sexual Behavior and Relationships

| Lifetime Sexual History | Percentage | N = 552 |

|---|---|---|

| Sexually active | ~100 | 550/552 |

| Median age in years of sexual initiation (vaginal sex) | 13 | 550 |

| Type of sexual relationships in the year prior to incarceration | ||

| Had long-term partner(s) only | 24 | 130/550 |

| Had short-term partners only | 21 | 115/550 |

| Had both long- and short-term partners | 54 | 294/550 |

| Had no sexual partners in the year prior to incarceration | 2 | 11/550 |

| Number of sexual partners in 3 months prior to incarceration | ||

| Had 3 or more vaginal sex partners | 43 | 236/548 |

| Condom use in 3 months prior to incarceration among sexually active | 517 | |

| Consistently used condoms when having sex | 32 | 167/517 |

| Of those with long-term partners, always used condoms with long-term partner | 31 | 121/391 |

| Of those with casual partners, always used condoms with casual partners | 60 | 214/356 |

| Attitudes toward violence and sex in relationships (percentage agree or strongly agree) | 552 | |

| Boy who hits girlfriend loves her | 13 | 74/551 |

| Violence between dating partners improves relationship | 8 | 46/551 |

| Girls sometimes deserve to be hit | 24 | 132/552 |

| Okay for a man to hit his wife | 10 | 55/551 |

| Most men want to go out with women just for sex | 84 | 465/552 |

| Boys sometimes deserve to be hit by the girls they date | 46 | 254/552 |

| Girls sometimes deserve to be hit by the boys they date | 24 | 132/552 |

For the most part, these young men did not ascribe to the attitudes about gender norms that have been attributed to “gangsta” culture or “hypermasculinity” in the popular and academic literature (Hine & Jenkins, 1999; Marriott, 2000; Mirande, 1997). For example, less than a quarter of the young men agreed with statements justifying violence within an intimate relationship. However, other responses suggest a more traditional approach to masculine norms. For example, 84% of participants agreed that “most men want to go out with women just for sex,” and 45% agreed that “boys sometimes deserve to be hit by the girls they date,” whereas only 24% agreed with “girls sometimes deserve to be hit by the boys they date,” suggesting more stereotypical attitudes about gender.

Finally, we asked young men about their top three priorities after they were released from jail. The two most frequent responses were unemployment (69%) and education (49%). Few young men identified health-related issues such as substance abuse (13%), psychological problems (5%), medical problems (2%), or HIV (1%) as priority problems.

Prior Intervention Studies

Our goal was to create an intervention that was tailored to the characteristics and life experiences of the young men who volunteered to participate in REAL MEN and based on the successes and limitations of prior intervention studies with incarcerated youth.

These studies fell into several categories. Most common were categorical programs designed to reduce HIV risk or substance abuse. These generally included information on HIV risk, skills development on condom use, and discussion of sexual relationships (Johnson, Carey, Marsh, Levin, & Scott-Scheldon, 2003; Schlapman & Cass, 2000; Shelton, 2001). A second program model, most often implemented in juvenile justice settings, provided comprehensive psychosocial services and often included family and school representatives (Blechman & Vryan, 2000; Curtis, Ronan, & Borduin, 2004; Dembo, Wothke, Livingston, & Schmeidler, 2002). A third more recent model is the reentry programs designed to facilitate transition from correctional facility to community (Freudenberg et al., 2005; Lowenkamp & Latessa, 2005; Reentry Policy Council, 2005; Travis et al., 2005).

Each model offered important lessons for the REAL MEN intervention but had shortcomings as well. For example, the categorical HIV programs addressed the need for culturally appropriate and explicit discussion of sexual behavior and for the development of practical condom skills. However, these programs often failed to address deeper gender issues that structured sexual behavior or to adequately acknowledge the range of social, economic, and discriminatory challenges that faced low income youth involved in the criminal justice system and thus made reducing HIV risk more difficult.

The more comprehensive systemic models addressed complex life situations more fully but often failed to capitalize on the strengths of youth and their families and communities. Although these programs take on school and family issues, they locate the problem within young people themselves and seek to change individuals, even though they enlist others in helping to support these changes.

Finally, the reentry programs appropriately focus on work, housing, and substance abuse, the priorities of adults returning from jail, and take on the challenge of involving multiple sectors and systems in reentry, often by seeking to change policies as well as individuals. To date, however, few of these programs have addressed the cultural and psychosocial issues that influence successful reentry (e.g., gendered norms, racism) and few have addressed the unique reentry experiences of youth.

THE INTERVENTION: REAL MEN

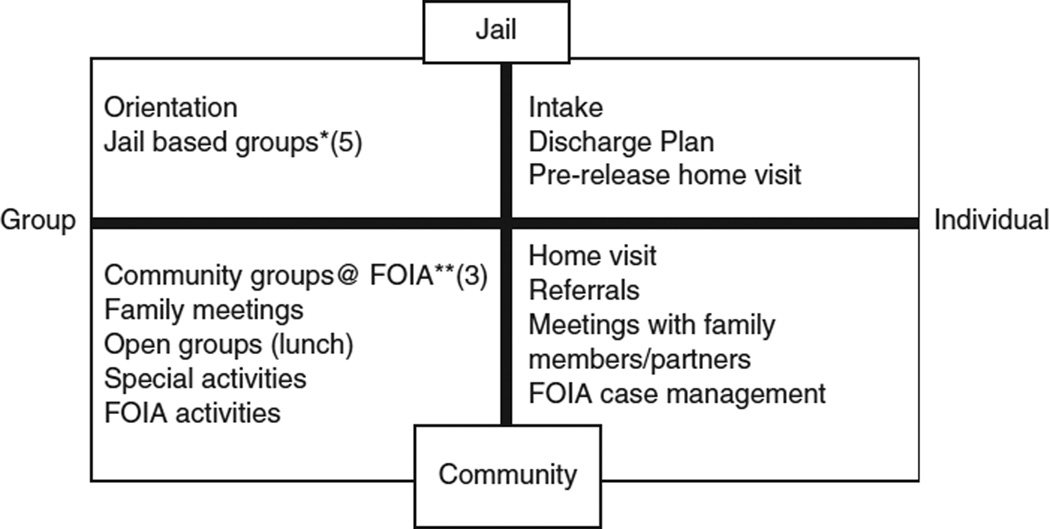

REAL MEN was designed to “fit” within the lives of young men leaving jail by addressing the ways that life circumstances and social constructions of masculinity, race, and class not only conspired to push young men into the path of HIV infection, violence, substance abuse, and incarceration, but also created opportunities for transformation (Schulz, Freudenberg, & Daniels, 2006; Schulz & Mullings, 2006). The intervention was based on pilot data and our previous interventions with adolescents (Freudenberg et al., 2005) and an adaptation of successful elements from other intervention models. Figure 1 provides an overview of intervention components.

FIGURE 1. Overview of REAL MEN Intervention.

NOTE: FOIA, Friends of Island Academy, REAL MEN’s community partner.

*Jail groups include (a) Getting Ready for Going Home, (b) Staying Healthy to Stay Free (and what about HIV?), (c) Being a REAL MAN in Today’s World, (d) Sex in the Risk Zone, and (e) My People, My Pride/Mi Gente, Mi Orgulla.

**Community groups include (a) Drugs in Your Life, (b) Getting the Information You Need to Stay Free and Healthy, and (c) Staying Free, Staying Healthy for life.

First, we decided to develop a short-term, transitional program. Prior work had shown that youth drop out of reentry programs earlier than adults (Needels, Stapulonis, Kovac, Burghardt, & James-Burdumy, 2004) although other evidence suggests that people leaving jail make critical decisions about sexual and drug behavior in the first hours and days after release (Mahon, 1996; Seal, Margolis, Sosman, Kacanek, & Binson, 2003). To change the lives of young men leaving jail requires engaging them at the time of release—a time of vulnerability and perhaps openness to change. Thus, REAL MEN was designed as a 30-hr intervention, most of which took place in jail where it was easy to engage young men and develop relationships. The remainder took place in the community in the month after release when risky behavior was likely.

Second, effective interventions need to address the basic issues that young men identify as priorities, school and work, and the psychosocial issues that influence sexual and drug behavior. Interventions that address only the first of these risk improving life circumstances without protecting health, leaving participants vulnerable to future harm. Interventions that address only single health problems may fail to engage young people, who seldom see health or substance abuse as a priority need. REAL MEN developed a partnership with a community-based organization, which offered General Educational Development (GED) and high school programs, job training, and a variety of other postrelease services to all participants. Thus, REAL MEN addresses risk behavior directly through health education and referrals for health care and indirectly by connecting participants to job training, education, and other services that offer pathways to healthy adulthood.

Third, effective interventions need to move beyond HIV information to focused consideration of traditional norms of masculinity. Using groups, discussion of contrasting views of masculinity in the media and popular culture and role plays, REAL MEN enlists young men in considering pathways to manhood that lower risk of HIV, violence, drug use, and reincarceration. Such alternatives are available within African American and Latino communities (Aronson et al., 2003) as evidenced by the diversity of attitudes about gender within our sample.

Fourth, young men’s identities as African Americans or Latinos can contribute to positive self-esteem and foster personal and community responsibility (Aronson et al., 2003; Canada, 1998; Marsiglia & Waller, 2002; Oyserman et al., 2003). In addition, interventions must acknowledge the reality of racism in young people’s lives and provide tools to address this. In group sessions, participants were asked to identify Black and Latino leaders and activists they recognized; then, program staff discussed the life experiences of these leaders (e.g., Malcolm X, Nelson Mandela, Che Guevara), emphasizing their success in overcoming incarceration and their civic engagement on behalf of their communities. Such exercises in the REAL MEN curriculum are designed to build on young men’s emerging racial/ethnic pride.

Fifth, to engage young men, programs should offer nonjudgmental guidance to participants to help them make choices that maintain health and avoid reincarceration. Calls for abstinence from drug use and sexual behavior may reflect adult values but can serve to alienate youth. Harm reduction approaches may be more effective in initiating behavioral changes that protect health (DesJarlais, 1995). REAL MEN staff encouraged participants to identify the specific patterns of drug use and sexual behavior that caused problems for them or the people they cared about and assisted them to identify acceptable ways of changing these behaviors.

REAL MEN also used ecological approaches to health promotion (Stokols, 1996). It provided services both inside the jail and after release as both settings are important in reentry. Similarly, REAL MEN worked at the individual and group levels. At the individual level, the program helped young men identify their own strengths, learn skills, and find resources to protect their health and stay free. It used groups to provide support for healthy behavior and to critically examine the social and political context in which young men of color live.

Finally, by combining elements from categorical, systemic, and reentry program models, REAL MEN operates in the cognitive, emotional, and sociopolitical realms. The program offers knowledge and skills that participants can use to protect their health and avoid reincarceration. It seeks to tap into young men’s desire for self-worth, intimacy, and feeling connected to others as well as their fears about isolation, failure, and threats to masculinity. Finally, the program helps participants to analyze their social circumstances and make choices that protect themselves and their communities.

In summary, REAL MEN seeks to increase young men’s chances of economic and social stability, and thus better health, by linking them to employment and educational opportunities after release from jail. The program also seeks to engage participants in a critical examination of how dominant social constructions of masculinity and race influence the contexts that they encounter and their own actions and health risks. In providing opportunities for young men to analyze and articulate these social processes, REAL MEN helps them identify within their life circumstances and communities opportunities that enhance their chances of staying out of jail and protecting the health and wellbeing of people they care about.

DISCUSSION

An assessment of the impact of participation in the REAL MEN program awaits analysis of the follow-up interviews with participants. However, preliminary results based on program data and qualitative interviews with program participants following the intervention and a review of case records by program staff suggest some findings reported here can guide future research and inform other interventions for this vulnerable population. First, our experience shows that it is possible to engage young men in jail in voluntary programs to address drug use and sexual behavior. Some have characterized these youth as “hard to reach,” but our experience is that incarcerated young men were eager to talk about their life circumstances with nonjudgmental staff willing to listen. After release from jail, this support plays an important role in successful reentry. As one participant explained in a postintervention interview, “I knew I had somebody supportin’ me. That alone, helped me to get where I wanted to be, right now. And stay out of jail.” Our experience suggests that many incarcerated youth are enthusiastic about joining programs, providing health professionals with a rationale for offering voluntary services. What young men reported valuing was a nonjudgmental ear and an opportunity to help them acquire the skills to navigate legitimate opportunity structures.

Program records on levels of participation provide additional insights into young men’s willingness to participate in voluntary programs. Of the 277 participants randomly assigned to the full intervention (jail and community-based services), 177 (64%) participated in at least 4 educational sessions; 112 (40%), made at least one visit to the community-based organization; 88 (32%) participated in 4 or more educational sessions and also visited the community-based organization, and 201 (73%) completed the follow-up interview 1 year after release from jail. Of the 275 assigned to jail services only (the comparison group), 47 (17%) made at least one visit to the community reentry program and 195 (71%) completed the follow-up interview 1 year after release from jail. These findings show that more than 70% of the young men who agreed to enroll in the study participated actively (i.e., completed both intake and follow-up interviews), and about one third participated at a more intensive level (i.e., engaged in both education sessions and community services). Thus, the more intensive services and more active outreach associated with assignment to the jail and community services group more than doubled community-based organization participation rates (40% vs. 17%).

Second, we found that different dynamics motivate participation in jail and after release. In jail, the harsh environment, boredom, and for some a newly discovered motivation to change their lives compel young men to seek programs such as REAL MEN. After release, many young men initially want to celebrate their return to the free world, often by using drugs or engaging in risky sexual behavior, and lose touch with some of the motivation for change. Later, however, the reality of negotiating the legitimate opportunity structures required to find a job, complete a GED, enter college, and avoiding reincarceration again assume salience providing renewed opportunities for intervention. The capacity of REAL MEN staff to help young men build the skills to succeed within legitimate opportunity structures was a significant benefit. As one participant noted, “Some people just don’t know, even a simple thing like filling a job application. And, help them with schools, help with a way to get in. Yo, when I went to [school] I didn’t know I had to do all that financial aid.” Navigating these structures often requires learning the skills that Elijah Anderson identifies as “code switching,” between skills that are effective in street life and those that are required in mainstream White society (Anderson, 2000). By recognizing the specific challenges and barriers that Black and Latino young men face when they try to navigate an opportunity structure that is predominantly White, programs can help young men to overcome the multiple forms of discriminations they encounter.

Third, most young men in this study reported that support from family and especially peers was important in sustaining their efforts at successful reentry. In fact, positive peer support in many instances countered the view of these young men as “hypermasculine” thugs who only want to dominate women. For example, one participant observed, “When I came home … I got with this girl and I promised her I wouldn’t get locked up, wouldn’t get in trouble. And to this day I’m still with her and not in jail, so she’s the one who really put that in my head.” However, fewer reported engagement with the jobs, schools, or civic, or political activities that focused on racial/ethnic identity that could also provide support. During reentry, these young men face overwhelming obstacles—multiple legal cases, school failure, unemployment, stigma, chronic illness, and prior experiences with crime and violence. Developing interventions that can acknowledge and build on these sources of support, yet also address the many deep-rooted problems at both individual and policy levels, is an important priority. REAL MEN focused on individuals, not policies; but in our other work with incarcerated populations, we have sought to integrate individual and policy interventions (Freudenberg et al., 2005). Whether an empowerment approach that prepares young men to advocate for policy changes could better integrate these two levels warrants consideration. This approach has helped incarcerated women cope with HIV and advocate for the services they needed (Boudin et al., 1999).

Fourth, White-dominated mainstream media images of young Black and Latino men often portray them as sexual predators fueled by misogyny (Hutchinson, 1997). Our findings contradict this stereotype and suggest a more complex reality in which young men often hold multifaceted views about gender and struggle with notions of masculinity that put their health at risk. Using different media images and teaching critical media literacy to explore these contradictions and engaging young men in articulating alternative pathways holds the promise of illuminating new and healthier roads to manhood (Bergsma, 2004).

Fifth, although some adults view substance use, violence, and sexual behavior as the issues to address with youth, these young men rarely identified these as priorities. Instead, they were concerned about work, school, and money. Finding better ways to develop interventions that start with the concerns of young people may better engage them in preventive interventions.

CONCLUSION

In summary, these findings challenge dominant views of youth involved in the criminal justice system in a number of ways. Most young men reported several sources of support in their daily lives, most identified school and work as their highest priorities after release, and many had more tolerant views toward women and intimate relationships than portrayed in mainstream media. At the same time, these young men reported high levels of marijuana and alcohol use, risky sexual behavior, many prior encounters with the criminal justice system and multiple life challenges. Few identified health as a priority. Our findings suggest that interventions that capitalize on the goals and assets these young men identify may be more successful than those that seek to impose adult values.

Contributor Information

Jessie Daniels, Urban Public Health at Hunter College in New York.

Martha Crum, Sociology Doctoral Program at the City University of New York-Graduate Center, New York.

Megha Ramaswamy, Sociology Doctoral Program at the City University of New York-Graduate Center, New York.

Nicholas Freudenberg, Urban Public Health at Hunter College in New York.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Arlington, VA: Author; 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Code of the street: Decency, violence and the moral life of the inner city. New York: Norton; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson RE, Whitehead TL, Baber WL. Challenges to masculine transformation among urban low-income African American males. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(5):732–741. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A. The importance of successful reentry to jail population growth. Paper presented at the Jail Reentry Roundtable; Washington, DC. 2006. Jun 27, [Google Scholar]

- Bergsma LJ. Empowerment education: The link between media literacy and health promotion. American Behavioral Scientist. 2004;48(2):152–164. [Google Scholar]

- Blechman E, Vryan K. Prosocial family therapy: A manualized preventive intervention for juvenile offenders. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2000;5(4):343–378. [Google Scholar]

- Boudin K, Carrero I, Clark J, Flournoy V, Loftin K, Martindale S, et al. ACE: A peer education and counseling program meets the needs of incarcerated women with HIV/AIDS issues. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 1999;10(6):90–98. doi: 10.1016/s1055-3290(06)60324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P. In search of respect: Selling crack in El Barrio. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Canada G. Reaching up for manhood: Transforming the lives of boys in America. Boston: Beacon; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Castrucci BC, Martin SL. The association between substance use and risky sexual behaviors among incarcerated adolescents. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2002;6(1):43–47. doi: 10.1023/a:1014316200584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clear TR, Rose DR, Waring E, Scully K. Coercive mobility and crime: A preliminary examination of concentrated incarceration and social disorganization. Justice Quarterly. 2003;20(1):33–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, Spear S, Scribner R, Kissinger P, Mason K, Wildgen J. Broken windows and the risk of gonorrhea. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(2):230–236. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Rose E, Levine D. Adjudication history and African American adolescents’ risk for acquiring sexually transmitted diseases: An exploratory analysis. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2003;30(8):634–638. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000085183.54900.B6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis NM, Ronan KR, Borduin CM. Multisystemic treatment: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(3):411–419. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Wothke W, Livingston S, Schmeidler J. The impact of a family empowerment intervention on juvenile offender heavy drinking: A latent growth model analysis. Substance Use and Misuse. 2002;37(11):1359–1390. doi: 10.1081/ja-120014082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DesJarlais DC. Harm reduction: A framework for incorporating science into drug policy. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:10–12. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Lanier MM, Horan PF, Lodico M. Comparison of AIDS knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among incarcerated adolescents and a public school sample in San Francisco. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81(5):628–630. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.5.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett WJ, DiIulio JJ, Walters JP. Body count: Moral poverty-- and how to win America’s war against crime and drugs. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J. The comparative advantage of juvenile versus criminal court sanctions on recidivism among adolescent felony offenders. Law and Policy. 1996;18(1–2):77–114. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin JR, Sykes MP. Living with racism: Middleclass Blacks experiences with racism. Boston: Beacon; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson AA. Bad boys: Public schools in the making of black masculinity. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest CB, Tambor E, Riley AW, Ensminger ME, Starfield B. The health profile of incarcerated male youths. Pediatrics. 2000;105(1 Pt 3):286–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N. Jails, prisons, and the health of urban populations: A review of the impact of the correctional system on community health. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78(2):214–235. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N, Daniels J, Crum M, Perkins T, Richie BE. Coming home from jail: The social and health consequences of community reentry for women, male adolescents, and their families and communities. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(10):1725–1736. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.056325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PM, Beck AJ. Prison and jail inmates at midyear 2005 (NCJ 213133) Washington, DC: Department of Justice; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hine DC, Jenkins E, editors. A question of manhood: A reader in U.S. black men’s history and masculinity. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Holzer HJ, Offner P, Sorenson E. Declining employment prospects among young Black less-educated men: The role of incarceration and child support. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2005;24(2):329–350. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson EO. The assassination of the Black male image. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Carey MP, Marsh KL, Levin KD, Scott-Scheldon LA. Interventions to reduce sexual risk for the human immunodeficiency virus in adolescents, 1985–2000. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157(4):381–388. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61(7):1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Napoli M, Marsiglia FF. Ethnic pride, biculturalism, and drugs use norms of urban American Indian adolescents. Social Work Research. 2002;26(2):101–112. doi: 10.1093/swr/26.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liam D. Environmental racial inequality in Detroit. Social Forces. 2006;85(2):771–796. doi: 10.1353/sof.2007.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenkamp CT, Latessa EJ. Developing successful reentry programs: Lessons from the What Works Research. Corrections Today. 2005;67:71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Mahon N. New York inmates’ HIV risk behaviors: The implications for prevention policy and programs. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(9):1211–1215. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.9.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marriott D. On Black men. New York: Columbia University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Waller M. Language preference and drug use among Southwestern Mexican American middle school students. Children and Schools. 2002;24(3):145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Massey D, Denton NA. American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the American underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mateu-Gelabert P, Lune H. School violence: The bidirectional conflict flow between neighborhood and school. City and Community. 2007;2(4):353–369. [Google Scholar]

- Messerschmidt JW. Masculinities and crime: Critique and reconceptualization of theory. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Messerschmidt JW. Nine lives: Adolescent masculinities, the body, and violence. Boulder, CO: Westview; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Miller JG. Search and destroy: African American males in the criminal justice system. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mirande A. Hombres y machos: Masculinity and Latino culture. Boulder, CO: Westview; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Morris RE, Harrison EA, Knox GW, Tromanhauser E, Marquis DK, Watts LL. Health risk behavioral survey from 39 juvenile correctional facilities in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1995;17:334–344. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00098-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski KN. Coping with perceived discrimination: Does ethnic identity protect mental health? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44(3):318–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullings L. Losing ground: Harlem, the war on drugs, and the prison industrial complex. Souls. 2001;5(2):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- National Commission on Correctional Health Care. The health status of soon-to-be-released inmates (a report to Congress) Chicago: Author; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Needels K, Stapulonis RA, Kovac MD, Burghardt J, James-Burdumy S. The evaluation of health link: The community reintegration model to reduce substance abuse among jail inmates: Technical report. Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Bybee D, Terry K. Gendered racial identity and involvement with school. Self and Identity. 2003;2:307–324. [Google Scholar]

- Pager D. The mark of a criminal record. American Journal of Sociology. 2003;108(5):937–975. [Google Scholar]

- Payne YA. “A gangster and a gentleman”: How street life-oriented, U.S.-born African men negotiate issues of survival in relation to their masculinity. Men and Masculinities. 2006;8(3):288–297. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7(2):156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Reentry Policy Council. Report of the reentry policy council: Charting the safe and successful return of prisoners to the community. New York: Council of State Governments; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Russell LD, Alexander MK, Corbo KF. Developing culture-specific interventions for Latinas to reduce HIV high-risk behaviors. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2000;11(3):70–76. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60277-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore J, Shelton JN. Cognitive costs of exposure to racial prejudice. Psychological Science. 2007;18(9):810–815. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277(5328):918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlapman N, Cass PS. Project: HIV prevention for incarcerated youth in Indiana. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 2000;17(3):151–158. doi: 10.1207/S15327655JCHN1703_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Freudenberg N, Daniels J. Intersections of race, class, and gender in public health interventions. In: Schulz AJ, Mullings L, editors. Gender, race, class and health: Intersectional approaches. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2006. pp. 371–393. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Mullings L, editors. Gender, race, class and health: Intersectional approaches. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Seal DW, Margolis AD, Sosman J, Kacanek D, Binson D. Project START study group. HIV and STD risk behavior among 18- to 25-year-old men released from U.S. prisons: Provider perspectives. AIDS Behavior. 2003;7(2):131–141. doi: 10.1023/a:1023942223913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton D. AIDS and drug use prevention intervention for confined youthful offenders. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2001;22(2):159–172. doi: 10.1080/01612840120509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sickmund M, Sladky TJ, Kang W. Census of juveniles in residential placement databook. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2005. Available at http://www.ncjrs.org/pdffiles1/ojjdp/fs200008.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Smith EP, Walker K, Fields L, Brookins CC, Seay RC. Ethnic identity and its relationship to self-esteem, perceived efficacy and prosocial attitudes in early adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 1999;22(6):867–880. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires GD, Kubrin CE. Privileged places: Race, residence and the structure of opportunity. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1996;10(4):282–298. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom KJ. Profile of state prisoners under age 18, 1985-97, special report (NCJ 176989) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Taxman FS, Byrne JM, Pattavina A. Racial disparity and the legitimacy of the criminal justice system: Exploring consequences for deterrence. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2005;16(4 Suppl B):57–77. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplin LA, Mericle AA, McClelland GM, Abram KM. HIV and AIDS risk behaviors in juvenile detainees: Implications for public health policy. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(6):906–912. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis J, Soloman AL, Waul M. From prison to home: The dimensions and consequences of prisoner reentry. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. Deadly symbiosis: When ghetto and prison meet and mesh. Punishment and Society. 2001;3(1):95–134. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead TL, Peterson J, Kaljee L. The “hustle”: Socioeconomic deprivation, urban drug trafficking, and low-income, African-American male gender identity. Pediatrics. 1994;93(6 Pt 2):1050–1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Collins C. U.S. socioeconomic and racial differences in health: Patterns and explanations. Annual Review of Sociology. 1995;21:349–386. [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Cultural, gender and psychosocial influences on HIV-related behavior of African-American female adolescents: Implications for the development of tailored prevention programs. Ethnicity and Disease. 1992;2(4):381–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe WA. Overlooked role of African-American males’ hypermasculinity in the epidemic of unintended pregnancies and HIV/AIDS cases with young African-American women. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2003;95(9):846–852. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamudio MM, Rios F. From traditional to Liberal racism: Living racism in the everyday. Sociological Perspectives. 2006;49(4):483–501. [Google Scholar]