Abstract

Objective. To describe the design, development, and the first 4 implementations of a Global Health elective course intended to prepare pharmacy students pursue global health careers and to evaluate student perceptions of the instructional techniques used and of skills developed during the course.

Design. Following the blended curriculum model used at Touro College of Pharmacy, the Global Health course combined team-based learning (TBL) sessions in class, out-of-class team projects, and online self-directed learning with classroom teaching and discussion sessions.

Assessment. Student performance was assessed with TBL sessions, team projects, and class presentations, online quizzes, and final examinations. A precourse and postcourse survey showed improvement in global health knowledge and attitudes, and in the perception of pharmacists’ role and career opportunities in global health. Significant improvement in skills applicable to global health work was reported and students rated highly the instructional techniques, value, and relevance of the course.

Conclusion. The Global Health elective course is on track to achieve its intended goal of equipping pharmacy students with the requisite knowledge and applicable skills to pursue global health careers and opportunities. After taking this course, students have gone on to pursue global field experiences.

Keywords: Global health, global health course, global health education, team-based learning, pharmacy education, elective course

INTRODUCTION

Globalization—the interrelation and interdependence of countries around the globe—has made the concept of global health a topical issue.1 Globalization has greatly facilitated the movement of populations, cultures, and diseases across national borders.1 Furthermore, globalization is altering the demographics of developed countries, and permanent residents or naturalized citizens of these countries, after visiting friends and family in their home countries, may return with diseases unfamiliar to health care practitioners in their countries of residence.2,3

Recognizing the need for competencies to address emerging health care challenges of globalization, students of medicine in many countries, including the United States, are advocating for the inclusion of global health courses in curricula.3 These didactic courses in global health often precede global field experiences. Medical schools that offer global health courses, with or without global field experiences, report short-term and long-term positive impacts on students.4-11 Graduates from such programs become more culturally competent, more likely to work with underserved populations or in primary care, and more knowledgeable and competent in tropical medicine.6,7,10,11 Furthermore, they become more aware of and sensitive to cost issues in health care. Sensitization and awareness of the importance of public health and preventive medicine result in increased enrollment in master’s in public health (MPH) programs after graduating from medical school.2-5 Such global health exposure seems to provide opportunity for developing “transnational competence,” a trait needed by the contemporary health care practitioner.12

Global health courses developed in medical or public health programs tend to have a medical or disease focus, although course content and context of course delivery varies.5,13 As a step toward content standardization, Houpt et al described 3 domains of competencies to be developed by medical students taking global health courses: burden of global diseases, traveler’s medicine, and immigrant health.14

Literature on didactic global health courses in pharmacy education is limited. Schellhase et al described a 2-credit hour elective pharmaceutical care course offered by Purdue University College of Pharmacy that prepared students for an advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) in Kenya.15 The course, which was jointly taught by Purdue faculty members and Kenyan pharmacists (via webinars), focused on disease state management and patient care in the context of the Kenyan health care system, pharmacy practice, and culture and made efforts to contrast this context with that of the United States.15 Travel preparation and language emersion in Kiswahili, the national language of Kenya and other countries of East Africa, were also important components of the course.15 Fincham discussed the need for global health education within the pharmacy curriculum in 2006.16 He called for the expansion of global health education and experiential practice experiences to prepare pharmacy graduates “wishing to take on more global responsibilities.”16 Fincham also called attention to the need for incorporating education about malaria and other such infectious diseases, which are responsible for global morbidity and mortality, into the PharmD curriculum.16

Pharmacists can contribute to the promotion of health globally, not only in clinical practice settings but also at the national policy or health system/program management level as advisors for pharmaceutical affairs. They can also serve as senior technical officers, directors, or consultants to multilateral agencies within and outside the United Nations (UN) system. In these roles, pharmacists would be functioning more as public health officials, using their expertise to help address medication-related global health challenges. These challenges include lack of access to essential medicines,17,18 irrational use of medicines,19-21 problems associated with drug donations during national and global disasters,22-26 and multi-drug resistant diseases including tuberculosis.27-30 Access to quality, efficacious, and affordable medicines, which are rationally used and well managed, we believe, is a global health challenge requiring the pharmacist’s leadership and expertise. Thus, while didactic global health courses in pharmacy education need to incorporate the management of diseases of global health importance in resource-limited settings, attention also needs to be given to imparting the knowledge and skills to address the medication-related global health challenges outlined above to expand the global health career opportunities of the pharmacist.

The objectives of this paper are to describe a global health elective course within a PharmD curriculum designed to provide pharmacy students with the requisite skills and knowledge to help them pursue global health careers in the public health arena and to examine students’ perceptions of the instructional techniques used and the skills set developed during the course. Specifically, this paper describes the course design and development and the first 4 years (2010-2013) of its implementation.

DESIGN

Global Health at Touro College of Pharmacy in New York, was a 15-week, spring semester elective course from the spring semester of 2010 until mid-2012 when a College-wide curricular rearrangement turned it into a fall semester course. Hence in 2012, the course was offered twice; as a spring semester course during the 2011-2012 academic year and also as a fall semester one in the 2012-2013 academic year. Second-year students in the college’s 4-year professional PharmD program (2 year didactic plus 2 year experiential) were eligible to enroll in the course. Students who enrolled in the spring semester course would have already taken the college’s 3 core public health courses. However, as a fall semester course for P2 students, enrolled students would complete this course before taking the third core public health course (Foundations of Public Health III-Epidemiology & Biostatistics) in the following spring semester. The Global Health course was not capped with respect to student enrollment.

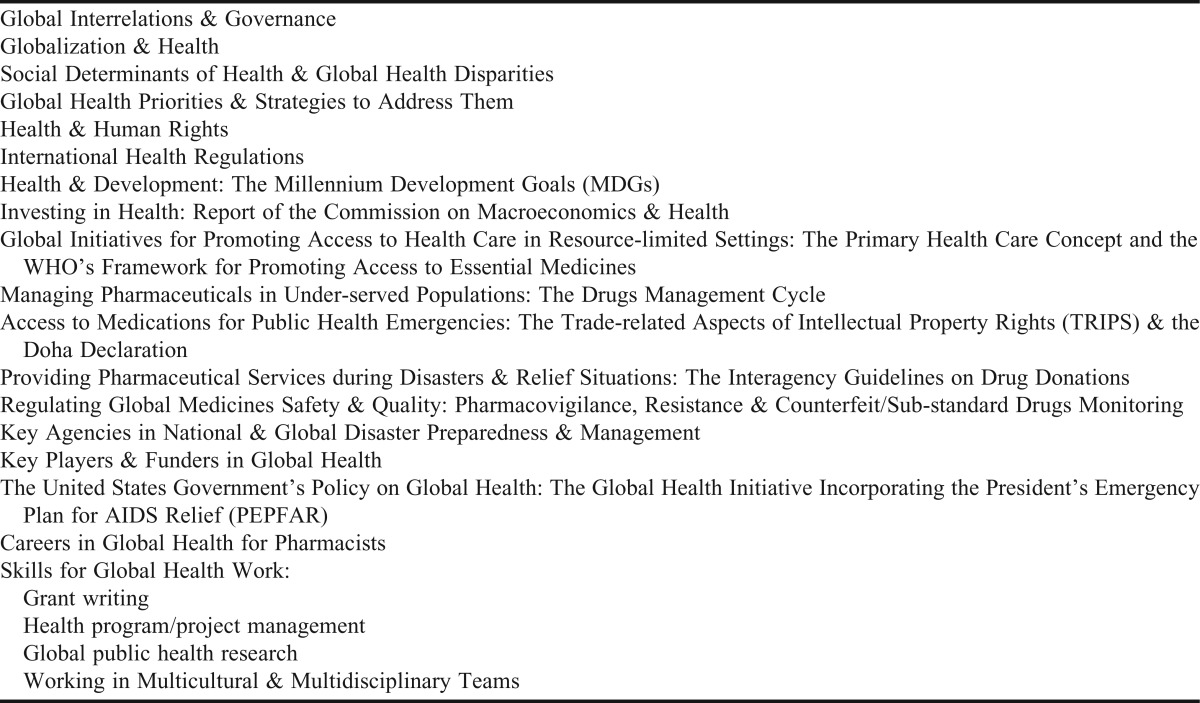

Table 1 presents the topical outline of the course; topics were systematically arranged to build on each other. The course began with an introduction to the concept of globalization and how it impacts global health. This was followed by issues/diseases of global health importance, then medication-related global health challenges, and the pharmacist’s role in addressing them. The course concluded with the development of applicable skills for global health work.

Table 1.

Topical Outline of Touro College of Pharmacy’s Global Health Course

At the beginning of the semester, students enrolled in the Global Health course were assigned to 5-6 teams that reflected the gender and racial/ethnic diversity of the class. Each team was assigned to one of the 6 regions of the world (European, Western Pacific, Eastern Mediterranean, African, the World Health Organization (WHO) regions of the Americas, and South East Asia) into which member states of the WHO have been grouped.31 For each WHO region, selected countries were identified and focused on in the course. Countries of focus in each region reflected the range of socioeconomic levels of development, disease burdens, population sizes, and similar distinguishing characteristics of countries in that region.31 When larger class sizes necessitated the creation of more than 6 student teams for the course, 2 or more teams were assigned the same WHO regions but given different countries within the said region to focus on. Student teams were required to change countries within their assigned WHO region for each project and TBL session in the course.

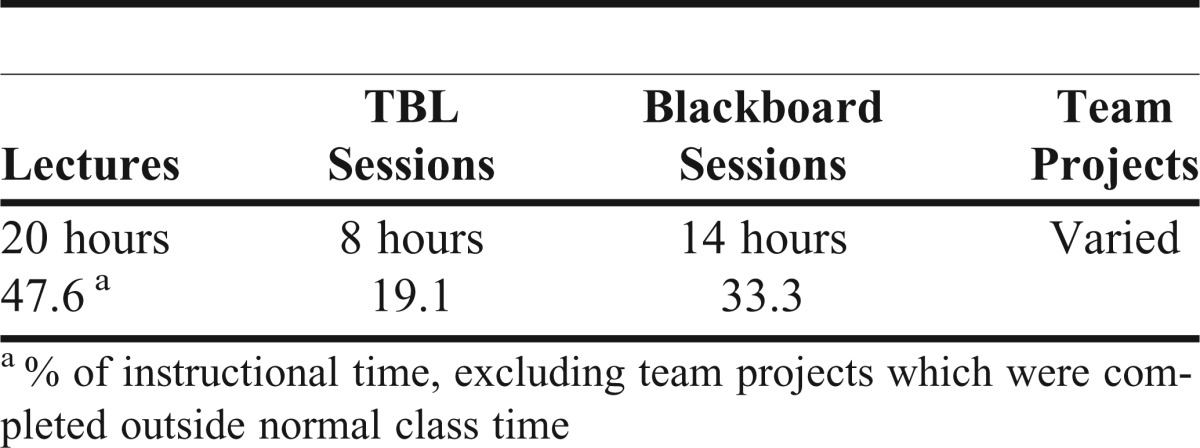

The Global Health elective course was a 3-credit hour course, which, following the school’s blended curriculum model, provided a 2-hour classroom session and a 1-hour online self-study session weekly on the school’s Blackboard Learning Management System (Blackboard Inc., Washington DC). To promote student accountability for online learning, quizzes were frequently attached, particularly to those topics pertaining directly to the pharmacist’s work in global health. Students were required to complete these quizzes and submit their responses on Blackboard before a programmed deadline. Instructional strategies in the course included classroom lectures and discussions and active-learning activities, particularly team-based learning (TBL) and team projects (Table 2). The team projects were undertaken outside of class. The face-to-face class sessions were devoted to teaching difficult concepts, introducing broad topics to be completed later on Blackboard, conducting TBL sessions, and presenting team projects.

Table 2.

Time Distribution of the Instructional Strategies Used in the Global Health Course

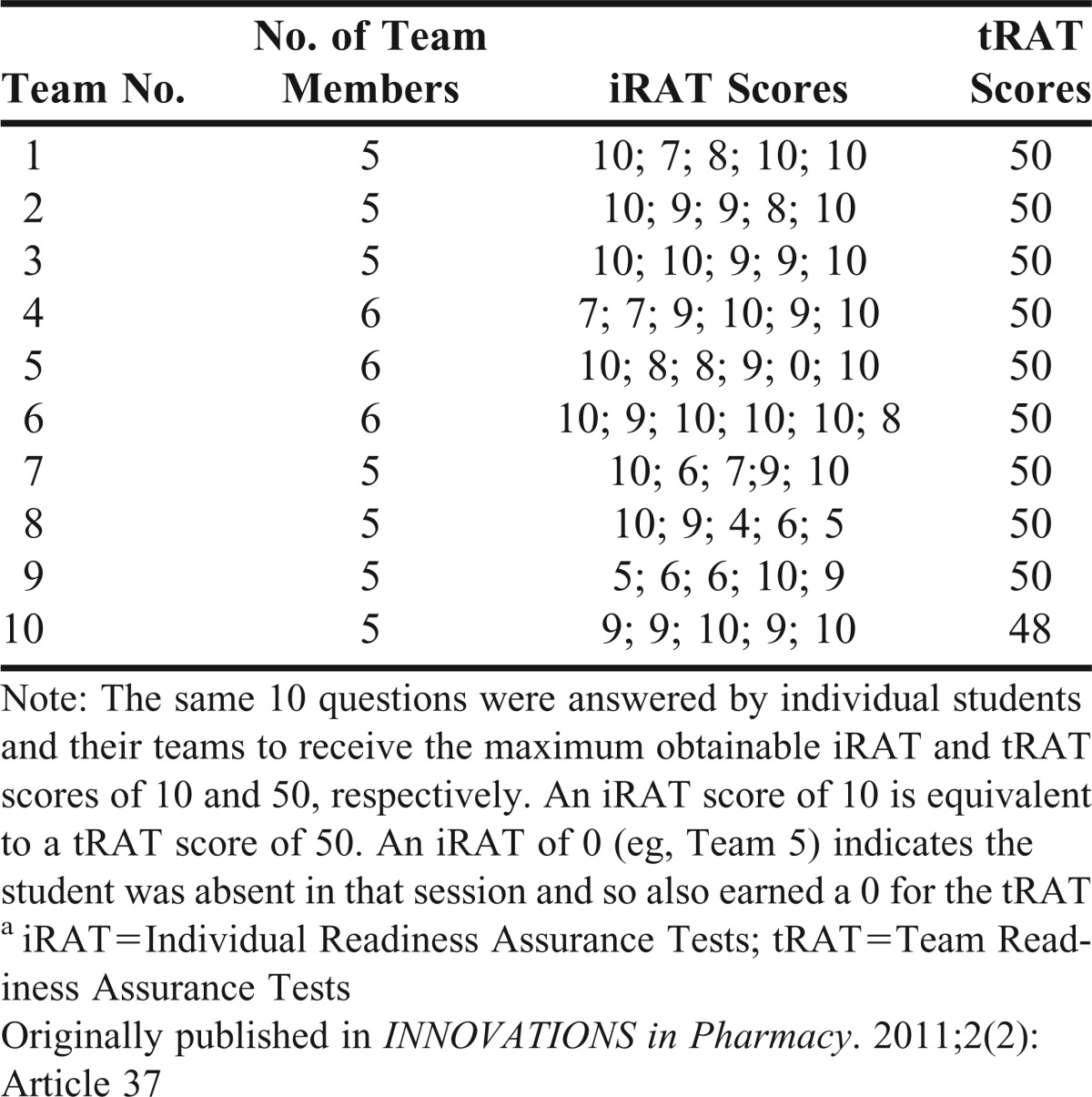

Although the same student teams worked in both the TBL sessions32 and team projects in the course, studies show that different dynamics are at play in these 2 instructional techniques.33,34 Michaelsen et al reported the transformational benefits of TBL on student learning. The benefits of TBL were found to include enhanced peer-to-peer interaction and the development of critical thinking and analytical skills.33,34 Four classroom periods in this course were TBL sessions (Table 2), which consisted of: (1) a preparatory phase where students were held accountable for topic-related materials posted on Blackboard 3-5 days before the TBL session; students were duly informed by e-mail about the posted materials; (2) the individual accountability phase in class where students completed the individual readiness assurance test (iRAT) consisting of a10-question, multiple-choice quiz on the topic for the day; (3) the team accountability phase, during which student teams completed the same quiz that individual students completed in the iRAT (team readiness assurance test, or tRAT); the rationale was to determine whether team interaction improved individual learning by comparing tRAT scores to iRAT scores of the individual team members; (4) the team application exercise, where student teams used course materials augmented by official web-based resources to address the same topic-related questions in different countries within their assigned WHO region; (5) the feedback session, facilitated by the professor, during which student teams learned about the concept(s) being studied as they related to countries or world regions other than those in which they had been working themselves. This cross fertilization of ideas enhanced the total learning experience of students.32

Two longitudinal team projects, designed for skills development, were important components of the course. A detailed description of the projects, student responsibilities, deadlines and formats for presentations, and grading rubrics were given in the course syllabus posted on Blackboard. This information was also reinforced during the course overview on the first day of class. Student teams were required to make 15-minute PowerPoint presentations of the first team project (the Country Profile project) in class.

The Country Profile project (Appendix 1) was designed to assist students in developing the ability to relate the health status and other health outcomes of a country’s population to their social determinants of health and available health-related resources. To make this project even more relevant to pharmacy, the teams were required to recommend 2 pharmaceutical interventions to assist in improving the health status of the most vulnerable population group(s) in their selected countries as part of their Country Profile Report and presentations. The second team project (Appendix 2) combined developing grant writing skills and undertaking a drug-related research program in resource-limited settings. Student teams searched for relevant grant makers and followed their guidelines to write a grant proposal to seek funding for a drug-related research program in a selected country within their assigned WHO region. Teams were required to select 1 of 3 developmental diseases, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis (TB), or malaria as their focus area for their research program, depending on which 1 of these 3 was the major public health concern in the selected country. Student teams were required to submit their grant proposal projects as Word documents and poster presentations for grading purposes. The poster presentation session, which was open to the student body and faculty members of the college, was eliminated in the spring 2012 course due to scheduling challenges.

Development of applicable skills for global health careers was an important goal in the course. Skills included team-building skills, specifically the ability to work in multi-disciplinary, multi-cultural, and multi-national teams, which was integrated in the course design and implementation and emphasized throughout the course. Students were taught that this was important because it reflected the usual work environment for professionals, including pharmacists, pursuing global health careers. Class participation was evaluated with unannounced class attendances taken throughout the semester and participation in class discussions.

Other skills to be developed in the course included health program management where student teams were charged to plan and implement a health educational intervention program intended to increase client uptake of various preventive health services. The theoretical basis for this component was the Health Belief Model. Other skills were grant writing,35 the ability to relate the health status of a country’s population to their social determinants of health and available health-related resources, management of pharmaceuticals in under-served populations (including selection, procurement, storage, distribution, and rational use as outlined in the Drug Management Cycle),36 provision of pharmaceutical services during disaster and relief situations, including planning and managing drug donations, and development of communication skills such as report writing, literature search, and information synthesis. Poster design and presentation were other skills developed in the course.

A guided tour of the United Nations (UN) headquarters in New York City was initially an optional component of the course. Students, accompanied by 1 or 2 professors, went on a guided tour to introduce students to the environment they would be working in if they chose to pursue global health careers. The tour also provided the students with a first-hand experience of how some of the course topics, such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) have been implemented to improve the health and wellbeing of populations around the world.

Global Health was taught by a 3-member Touro faculty team with global health career experience and/or interest. It was not possible to identify any 1 textbook as the required text for the course because the breadth of topics covered was not captured in a single textbook. Several reference sources, including Introduction to Global Health and Global Health 101 were included in the course syllabus and copies of these were available at the college’s medical library.37,38 Official websites of global agencies and electronic global documents, policies, guidelines, and agreements were made available to students as external course links through Blackboard. Sources used in the preparation of course lectures were also listed at the end of each PowerPoint lecture material. Key content sources for the Global Health course are listed in Appendix 3.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

Total course enrollment at the time of this writing was 240 students, which included 80.3% of the class of 2012 (n=66), 80.3% of the class of 2013 (n=76), 44.3% of the class of 2014 (n=88), 59.8% of the class of 2015 (n=102), and 25.5% of the class of 2016 (n=102). More elective course offerings in the program led to a decrease in course enrollment over the years.

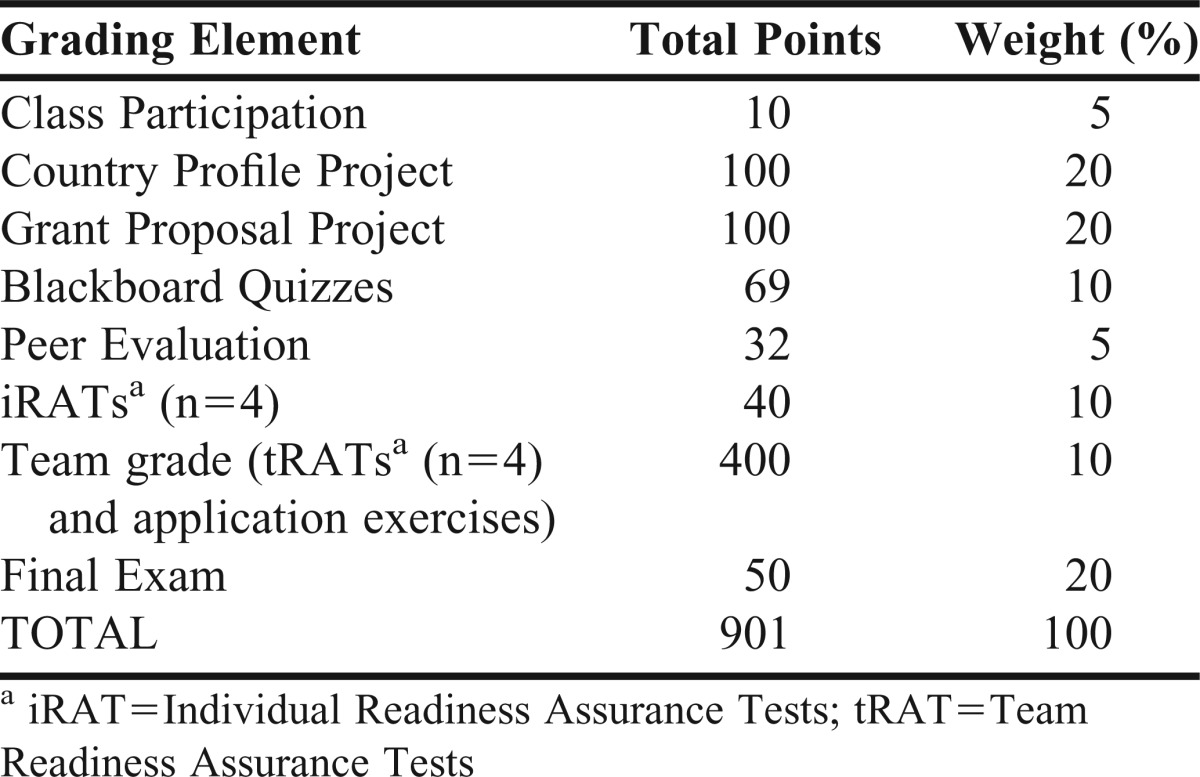

A variety of instructional and assessment techniques were used in the course to promote active student engagement and learning throughout the course. Student assessments (Table 3) included iRATs, tRATs, and team application exercises that made up each TBL session, Blackboard quizzes, team projects, class participation, peer evaluation of contribution to team effort, and a final examination. Table 4 provides evidence that individual learning was enhanced by the team interaction during the tRAT.32 Such enhancement was also reported by earlier studies.33-34

Table 3.

Grading for the Global Health Course

Table 4.

iRATa and tRATa Scores in a Team-based Learning (TBL) Session on Macroeconomics and Health

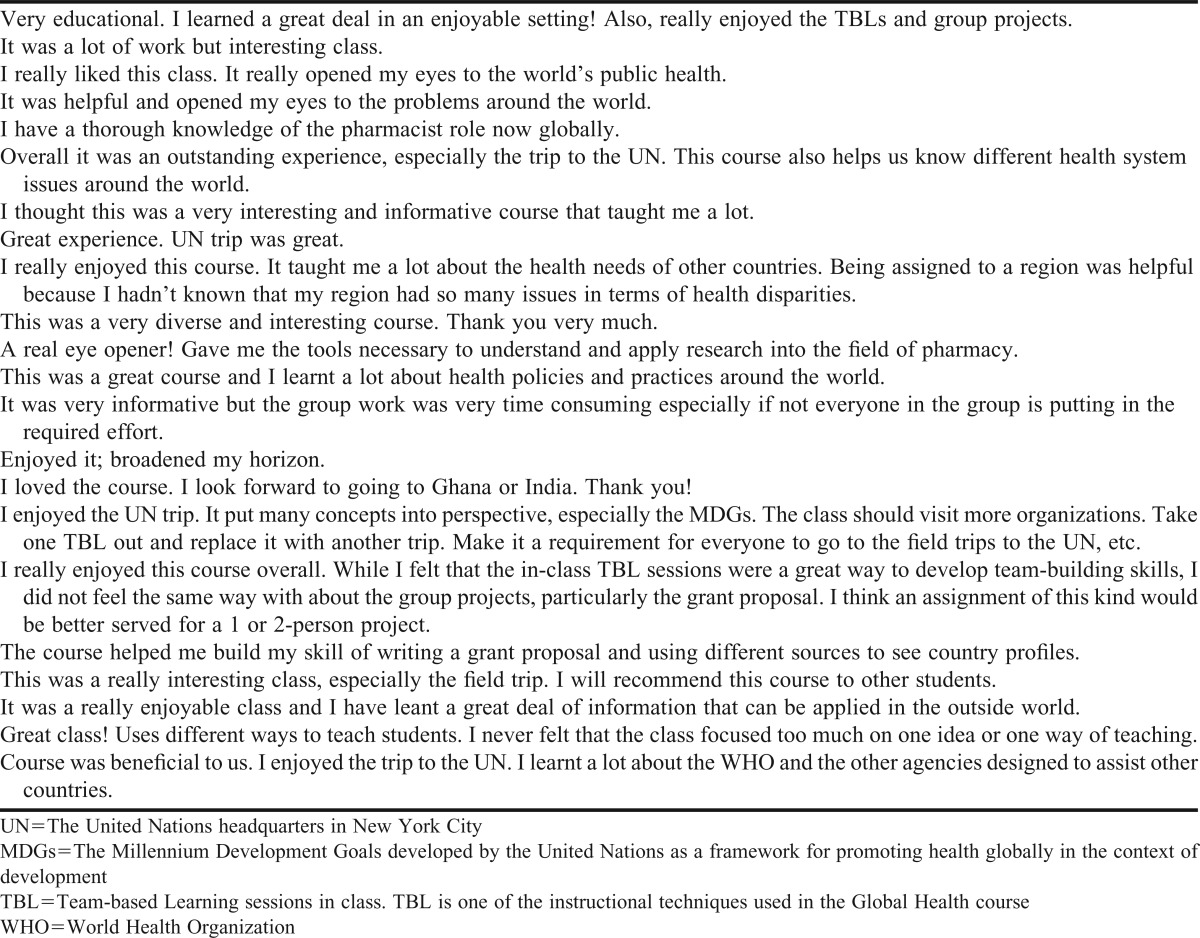

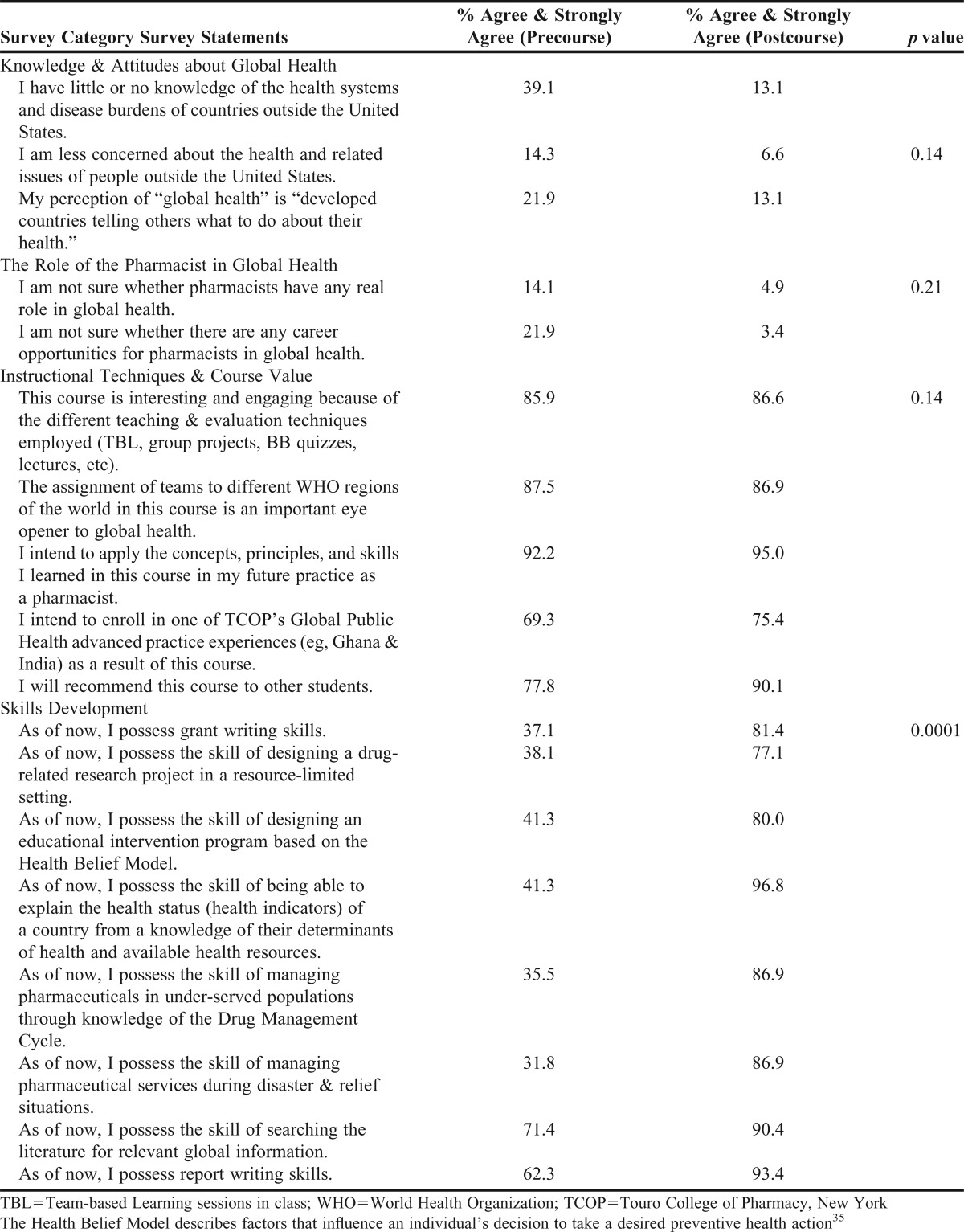

Students enrolled in the spring and fall 2012 courses (n=100) completed anonymous, voluntary, precourse and postcourse surveys, which were used to examine students’ knowledge of and attitudes about global health, their perceptions of the role and career opportunities for the pharmacist in global health, the instructional techniques used in the course, and the skill sets developed in the course. The survey consisted of a 5-item Likert Scale (strongly agree; agree; neutral/undecided; disagree; strongly disagree) to examine their level of agreement with the survey statements and open-ended questions to note their overall impressions of and experiences with the course and recommendations for course improvement (Table 5). The project was approved by Touro College Health Sciences Institutional Review Board as an exempt study.

Table 5.

Selected Students’ Overall Impressions/Experiences with the Global Health Course and Recommendations for Course Improvement (Spring & Fall 2012)

The students were 65% female; 58% reported being born outside the United States, and all but 12% had travelled outside the country before. Results of the students’ precourse and postcourse perception survey (Table 6) revealed a notable improvement in their knowledge of and attitudes about global health, although the difference was not significant. Similarly, although 14.1% of students were not sure whether pharmacists had any role in global health and 21.9% were skeptical of career opportunities for pharmacists in global health at the beginning of the course, both figures had fallen below 5% (4.9% and 3.4%, respectively) by the end of the course. Students reported high engagement and interest in the course as a result of the variety of instructional techniques used and other course activities, especially the UN tour. Students also perceived the course as being valuable (Tables 5 and 6).

Table 6.

Students’ Knowledge, Attitudes, Perceptions and Skills in Global Health: Precourse and Postcourse Survey Results

Survey findings showed significant (p=0.0001) improvement in the applicable skills for global health careers that the course sought to develop in students, including grant writing, global health research in a resource-limited setting, and management of pharmaceutical services during national and global disasters.

DISCUSSION

This paper presents the development, implementation, evaluation, and assessment of a pharmacy-relevant Global Health elective course, within a blended PharmD curriculum, designed to prepare students for global health careers. The course content and delivery were innovative in pharmacy education, and the goal was to maximize student interest and engagement in the course and to increase its relevance and applicability to the practicing pharmacist. Attention was given to the course structure and content to reflect conditions under which health professionals, including pharmacists, work in a global health work environment. Thus, the ability to function productively and professionally in multidisciplinary and multinational teams was emphasized as being critical for the successful career of the pharmacist in global health. This explains why peer evaluation of contribution to team effort and class participation were important contributors to the grading scheme in the course (Table 3).

Course improvement was ongoing in direct response to students’ feedback and recommendations. The guided tour of the United Nations (UN) was a particularly well-liked component of the course. It was interesting, for example, to see the students’ excitement at seeing the hall-length display of the MDGs in action by different UN agencies globally. Students also learned about the work of the UN and its agencies, enabling them to see career potential in global health and how they could make a difference with their skills and knowledge set. Students’ evaluation, feedback, and recommendation for course improvement turned the UN guided tour into a mandatory component of the course in the fall 2012 course (Table 5).

In July 2011, the college made this elective course a prerequisite for all Global Public Health advanced practice experience (APE) offerings. An expanded version of the Country Profile Project in this course was also approved by the College’s Global Education Committee for use as additional pretravel preparation for students going on global APEs, because a 2-semester time lapse exists between the completion of this course and the summer global APEs that take place in the students’ third year in the PharmD program. Students from the course have since enrolled in and completed APPE courses in Ghana, Haiti, and India, and 1 student completed a 3-month summer internship with the Essential Medicines and Policy Department of WHO headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, assisting in the review process for the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines. The WHO Essential Medicines Program assists low and middle income countries around the world in developing National Essential Medicines Lists in an effort to maximize their limited resources and improve the overall health care of their population; it’s one of the topics studied in the Global Health course. This student was also invited to participate in a second 3-month summer internship, this time to work in the Department of Patient Safety. A second student has also completed a WHO Geneva internship with the Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases Department. Other students are pursuing similar pharmacy-related global health opportunities.

SUMMARY

The Global Health elective course offered by the Touro College of Pharmacy in New York is on track to achieve its intended goal of equipping pharmacy students with the requisite knowledge and applicable skills to pursue global health careers and opportunities. After taking this course, students have gone on to pursue global field experiences for which the Global Health course has become a prerequisite at the school. Students have consistently rated the course high for its value, relevance, and engaging instructional techniques. It would be interesting to monitor the proportion of students who actually end up with global health careers after taking this course.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank Christine Greaves, administrative assistant of the Department of Social/Behavioral/Administrative Sciences at Touro College of Pharmacy in New York for her assistance with data entry.

Appendix 1. Country Profiles & Class Presentations (First Team Project)

The objective of this project is to assist students to understand and appreciate the interrelations between a country’s social determinants of health, its available health-related resources, and its health status and outcomes. Each group will select 1 country in their assigned WHO region for this project. The group will write a 6-page country profile that seeks to relate the social determinants of health, available health-related resources, and the health of the population (distribution of disease burden, health indicators, and outcomes). The country profile paper should follow the following outline:

1) Geography: including map indicating country location in the world map, capital city, national flag, etc.

2) Governance & Current Political Situation: regional/provincial/district divisions; democratically-elected government; history of/current military regimes; civil strife/political stability; degree of freedom (eg of the press and population)

3) Population: size; urban/rural distribution

4) People: gender and age structure, major ethnic groupings etc; percentage with available of water and sanitation, education/literacy rate

5) Economy: Gross domestic product (GDP), GDP per capita, major industries (eg, mining, agriculture); % contribution to GDP by sector of economy or industry; natural resources, major export commodities; % of population below the poverty line, etc.

6) Structure of the Health Care System/Healthcare Administration: relative importance of the public and private health sectors, health infrastructure: distribution of health facilities (eg, central/regional/district set up for service delivery, both curative and preventive services)

7) Financing of Health Care: Taxes? Out-of -pocket payment? Insurance-public/private? Single or multiple payer system?

8) Health-related Resources: health expenditure as a % of the GDP; health expenditure per capita; health manpower (doctor: population ratio; same for nurses and pharmacists); health manpower distribution in the country, (ie, rural vs urban).

9) Health-related, Pharmacy-specific Resources: Availability of Essential Medicines List (EML) for the country, region, or hospital facilities? How frequently are these updated? Describe the requirements for registration to practice pharmacy in the country (type of degree, years of training, experiential training before or after graduation, etc).

10) Major Health Problems and Their Epidemiology in the Country: infectious/non-infectious health problems; top 10 causes of morbidity/mortality; health indicators (eg, life expectancy at birth, mortality rate, infant mortality, under five mortality)

11) How the Social Determinants of Health in 1-9 above explain and/or contribute to the health problem(s) in 10.

12) Evidence of Health Disparities in the Country and Assessment of at Least 2 Factors Contributing to These Disparities.

13) Two Current Initiatives by the Country’s authorities to improve health by addressing selected social determinants of health (eg water and sanitation, nutrition, education)

14) Recommend 2 pharmaceutical interventions that may help to improve the health of the most vulnerable population group in the country.

The team will be responsible for researching the topic and providing a 15-minute (including 3-minutes discussion period) PowerPoint class presentation. Each team will also submit a written paper delineating the main points of the presentation. All students must sign the research paper that will be given to the professor.

This team project will carry a total of 100 points distributed as follows:

a) Completed research paper: 60 points

b) Class presentation: 30 points

c) Time management during presentation: 10 points

d) Total: 100 points

Research Paper Format: typed, double-spaced, Times New Roman, 12 point size fonts, not to exceed six (6) pages in length, using the AMA reference style for both the in-text and reference list.

Appendix 2. Written Grant Proposal to Finance a Research Project in a Resource-Limited Setting (Second Team Project)

This project is to assist students in developing grant writing skills and skills for undertaking a medication-related research program in a resource-limited global setting. Each team will develop a drug-related research proposal addressing one developmental disease (HIV/AIDS, Malaria, or Tuberculosis) of highest public health concern in a developing country within the team’s assigned WHO region.

Teams will use the interactive WHO Statistical Information System (WHOSIS) available at http://apps.who.int/whosis/data/Search.jsp?indicators=%5bIndicator%5d.%5HSC%5d. Members will collect the appropriate background information (health indicators) on their selected country to be able to identify which of the 3 developmental diseases and which segment of the population to target for their research proposal. Students can also access their selected country’s basic health indicators and health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) through their WHO regional sites at: http://www.who.int/about/regions/en/index.html.

Each team will search for a grant-funding source whose focus includes their chosen area of research. The team will write their grant proposal following the guidelines provided by the grant-making organization. If unsuccessful in the search, teams should write their grant proposal following the outline below:

a) Summary or abstract (250 words)

b) Background and significance of the research topic or focus

c) Specific aims or objectives of the research project

d) Methodology, including research design, target population, sampling issues, IRB, data collection methods and analysis, etc

e) Research team description, including a description of the health care team in the chosen country to work with to achieve research objectives

f) Resources, including specific locations for the study, personnel, and facilities available or required to complete research project

g) References: literature cited in the write-up (use the AMA reference style for both the in-text and reference list citations)

h) Dissemination of research results (how and where research findings will be disseminatedr)

i) Biographical sketches of the principal investigators (student team members)

- j) Budget, including following sections:

- • Direct costs, include student tuition, consultant fees, research-related travel, equipment, materials and supplies, support for research participants etc.

- • Indirect costs (also known as facilities and administrative (F&A Costs); 20% of direct costs)

Appendix 3. Key Sources Used for the Development of the Global Health Course Content

• United Nations. Charter of the United Nations. http://www.un.org/en/documents/charter Accessed May 22, 2014.

• World Health Organization. Globalization, TRIPS, and Access to Pharmaceuticals: WHO Policy Perspectives on Medicines. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js2240e Accessed May 22, 2014.

• Nair, MD. TRIPS and Access to Affordable Medicines. Journal of Intellectual Property Rights. 2012;17:305-314.

• United Nations. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr Accessed May 22, 2014.

• World Health Organization. The Right to Health. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs323/en/index.html Accessed May 22, 2014.

• World Health Organization. International Health Regulations, 2005, 2nd Edition. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241580410_eng.pdf?ua=1 Accessed May 22, 2014.

• World Health Organization. Investing in Health: A Summary of the Findings of the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. http://www.who.int/macrohealth/infocentre/advocacy/en/investinginhealth02052003.pdf Accessed May 22, 2014.

• World Health Organization. Tough Choices: Investing in Health for Development. Experiences from National Follow-up to the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. http://www.who.int/macrohealth/documents/report_and_cover.pdf?ua=1 Accessed May 22, 2014.

• United Nations. The Millennium Development Goals Report, 2013. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/report-2013/mdg-report-2013-english.pdf Accessed May 22, 2014.

• Kaiser Family Foundation. The U.S. Government’s Global Health Policy Architecture: Structure, Programs, and Funding April 2009. http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/7881_es.pdf Accessed May 22, 2014.

• World Health Organization. Guidelines for Medicines Donations. Revised 2010. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241501989_eng.pdf Accessed May 21, 2014.

• Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Strategic National Stockpile. http://www.bt.cdc.gov/Stockpile Accessed May 21, 2014.

• Central Intelligence Agency. The World FactBook. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/ Accessed May 22, 2014.

• Harrington TV. Pharmaceuticals in Disasters. In Hogan and Burstein’s Disaster Medicine 2nd Ed., Chapter 6. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. 2007; PP 56-63.

• Stewart K, and Sewankambo N. Okukkera Ng’omuzungu (lost in translation): Understanding the social value of global health research for HIV/AIDS research participants in Uganda. Global Public Health. 2010;5(2):164-180.

• US Department of Health & Human Services. Applying for Grant Opportunities on Grants.Gov. http://www.grants.gov/applicants/apply_for_grants.jsp Accessed May 22, 2014.

• Foundation Center. Identifying Funding Sources: Foundation Grants to Individuals Online. http://foundationcenter.org/findfunders/fundingsources/gtio.html Accessed May 22, 2014.

• Hodges BC; Videto DM. Assessment and Planning in Health Programs. Sudbury, MA. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Inc, 2005.

• WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2008/WHO_IER_CSDH_08.1_eng.pdf Accessed May 21, 2014.

• Pharmacists Without Borders-Canada. http://www.psfcanada.org/index.php?lang=en Accessed May 22, 2014.

• United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Global Health Programs. Progress Report to Congress, FY 2012. http://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1864/CSH-finalwebready.pdf Accessed May 22, 2014.

• United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). http://ochaonline.un.org Accessed January 28, 2014.

• United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Global Humanitarian Policy Forum. http://www.unocha.org/what-we-do/policy/events/global-humanitarian-policy-forum Accessed May 22, 2014.

• Doctors without Borders. http://www.doctorswithoutborders.org Accessed May 22, 2014.

• The International Red Cross & Red Crescent Movement. The Magazine of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. http://www.redcross.int/EN/mag/magazine2009_2/index.html Accessed May 22, 2014.

• World Health Organization. Operational Principles for Good Pharmaceutical Procurement. http://www.who.int/3by5/en/who-edm-par-99-5.pdf Accessed May 21, 2014.

• World Health Organization. Essential Drugs in Brief. http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/brief/en/index.html Accessed May 21, 2014.

• World Health Organization. Declaration of Alma-Ata. International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6-12 September, 1978. http://www.who.int/publications/almaata_declaration_en.pdf Accessed May 22, 2014.

• UNICEF. Primary Health Care: 30 Years Since Alma-Ata. http://www.unicef.org/sowc09/docs/SOWC09-Panel-2.2-EN.pdf Accessed May 21, 2014.

• World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2008-Primary Health Care-Now More than Ever. http://www.who.int/whr/2008/08_overview_en.pdf?ua=1 Accessed May 22, 2014.

• World Health Organization. Equitable Access to Essential Medicines: A Framework for Collective Action-WHO Policy Perspectives on Medicines, No. 008, March 2004. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2004/WHO_EDM_2004.4.pdf Accessed May 22, 2014.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, et al. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet. 2009;373(9679):1993–1995. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bacaner N, Stauffer B, Boulware DR, Walker PF, Keystone JS. Travel medicine considerations for North American immigrants visiting friends and relatives. JAMA. 2004;291(23):2856–2864. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tissingh EK. Medical education, global health and travel medicine: a modern student’s experience. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2009;7(1):15–18. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Medical Student Association. The International Federation of Medical Student Association (IFMSA) http://www.amsa.org Accessed 5/21/2014.

- 5.Izadnegahdar R, Correia S, Ohata B, et al. Global health in Canadian medical education: current practices and opportunities. Acad Med. 2008;83(2):192–198. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816095cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bissonette R, Route C. The educational effect of clinical rotations in nonindustrialized countries. Fam Med. 1994;26(4):226–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godkin MA, Savageau JA. The effect of a global multiculturalism track on cultural competence of preclinical medical students. Fam Med. 2001;33(3):178–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imperato PJ. A third world international health elective for U.S. medical students: the 25-year experience of the State University of New York, Downstate Medical Center. J Community Health. 2004;29(5):337–373. doi: 10.1023/b:johe.0000038652.65641.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pust RE, Moher SP. A core curriculum for international health: evaluating ten years’ experience at the University of Arizona. Acad Med. 1992;67(2):90–94. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramsey AH, Haq C, Gjerde CL, Rothenberg D. Career influence of an international health experience during medical school. Fam Med. 2004;36(6):412–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson MJ, Huntington MK, Hunt DD, Pinsky LE, Brodie JJ. Educational effects of international health electives on U.S. and Canadian medical students and residents: a literature review. Acad Med. 2003;78(3):342–347. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200303000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koehn PH, Swick HM. Medical education for a changing world: moving beyond cultural competence into transnational competence. Acad Med. 2006;81(6):548–556. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000225217.15207.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California. Global Health Scholars Program. http://keck.usc.edu/About/Administrative_Offices/Global_Health_Scholars_Program.aspx. Accessed May 22, 2014.

- 14.Houpt ER, Pearson RD, Hall TL. Three domains of competency in global health education: recommendations for all medical students. Acad Med. 2007;82(3):222–225. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180305c10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schellhase EM, Miller ML, Ogallo W, Pastakia SD. An elective pharmaceutical care course to prepare students for an advanced pharmacy practice experience in Kenya. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(3) doi: 10.5688/ajpe77360. Article 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fincham JE. Global public health and the academy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(1) doi: 10.5688/aj700114. Article 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Day RO, Birkett DJ, Miners J, Shenfield GM, Henry DA, Seale JP. Access to medicines and high-quality therapeutics: global responsibilities for clinical pharmacology. Med J Aust. 2005;182(7):322–323. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hale VG, Woo K, Lipton HL. Oxymoron no more: the potential of nonprofit drug companies to deliver on the promise of medicines for the developing world. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(4):1057–1063. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.4.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Awad AI, Ball DE, Eltayeb IB. Improving rational drug use in Africa: the example of Sudan. East Mediterr Health J. 2007;13(5):1202–1211. doi: 10.26719/2007.13.5.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manyemba J, Dzuda C, Nyazema NZ. Rational drug use. Part I: the role of national drug policies. Cent Afr J Med. 2000;46(8):229–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Massele AY, Nsimba SE, Rimoy G. Prescribing habits in church-owned primary health care facilities in Dar Es Salaam and other Tanzanian coast regions. East Afr Med J. 2001;78(10):510–514. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v78i10.8958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aloy B, Siranyan V, Dussart C. [Stopping the use of unused drugs for humanitarian purposes: stakes and perspectives. Ann Pharm Fr. 2009;67(6):414–418. doi: 10.1016/j.pharma.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker BK, Ombaka E. The danger of in-kind drug donations to the Global Fund. Lancet. 2009;373(9670):1218–1221. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61487-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bussieres JF, St Arnaud C, Schunck C, Lamarre D, Jouberton F. The role of the pharmacist in humanitarian aid in Bosnia-Herzegovina: the experience of Pharmaciens Sans Frontieres. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34(1):112–118. doi: 10.1345/aph.19157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinheiro CP. Drug donations: what lies beneath. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(8):580–58A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.048546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stehmann I. The Medicines Crossing Borders Project–improving the quality of donations. Trop Doct. 2004;34(2):65–66. doi: 10.1177/004947550403400202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Espinal MA, Laserson K, Camacho M, et al. Determinants of drug-resistant tuberculosis: analysis of 11 countries. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5(10):887–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loddenkemper R, Hauer B. Drug-resistant tuberculosis: a worldwide epidemic poses a new challenge. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107(1-2):10–19. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Telzak EE, Chirgwin KD, Nelson ET, et al. Predictors for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among HIV-infected patients and response to specific drug regimens. Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS (CPCRA) and the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG), National Institutes for Health. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999;3(4):337–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wells CD, Cegielski JP, Nelson LJ, et al. HIV infection and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: the perfect storm. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(Suppl 1):S86–107. doi: 10.1086/518665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. WHO Regional Offices. http://www.who.int/about/regions/en/Accessed 5/22/2014.

- 32.Addo-Atuah J. Performance and perceptions of pharmacy students using team-based learning (TBL) within a global health Course. INNOVATIONS in pharmacy. 2011;2(2) Article 37. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michaelsen LK, Knight AB, Fink LD. Team-based Learning: A Transformative Use of Small Groups. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michaelsen L. Team-based learning in large classes. In: Michaelsen L, Knight A, Fink L, editors. Team-based Learning: A Transformative Use of Small Groups. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. pp. 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boston University School of Public Health. Behavioral Change Models-The Health Belief Model. http://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/MPH-Modules/SB/SB721-Models/SB721-Models2.html. Accessed May 22, 2014.

- 36.Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The Drug Management Cycle. http://ocw.jhsph.edu/courses/pharmaceuticalsmanagementforunder-servedpopulations/PDFs/Session4.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2014.

- 37.Jacobsen KH. Introduction to Global Health. Jones & Bartlett Publishers; Sudbury, MA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skolnik R. Global Health 101. Second Ed. Jones & Bartlett Learning; Burlington, MA: 2012. [Google Scholar]