Abstract

Purpose

111In (typically as [111In]oxinate3) is a gold standard radiolabel for cell tracking in humans by scintigraphy. A long half-life positron-emitting radiolabel to serve the same purpose using positron emission tomography (PET) has long been sought. We aimed to develop an 89Zr PET tracer for cell labelling and compare it with [111In]oxinate3 single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).

Methods

[89Zr]Oxinate4 was synthesised and its uptake and efflux were measured in vitro in three cell lines and in human leukocytes. The in vivo biodistribution of eGFP-5T33 murine myeloma cells labelled using [89Zr]oxinate4 or [111In]oxinate3 was monitored for up to 14 days. 89Zr retention by living radiolabelled eGFP-positive cells in vivo was monitored by FACS sorting of liver, spleen and bone marrow cells followed by gamma counting.

Results

Zr labelling was effective in all cell types with yields comparable with 111In labelling. Retention of 89Zr in cells in vitro after 24 h was significantly better (range 71 to >90 %) than 111In (43–52 %). eGFP-5T33 cells in vivo showed the same early biodistribution whether labelled with 111In or 89Zr (initial pulmonary accumulation followed by migration to liver, spleen and bone marrow), but later translocation of radioactivity to kidneys was much greater for 111In. In liver, spleen and bone marrow at least 92 % of 89Zr remained associated with eGFP-positive cells after 7 days in vivo.

Conclusion

[89Zr]Oxinate4 offers a potential solution to the emerging need for a long half-life PET tracer for cell tracking in vivo and deserves further evaluation of its effects on survival and behaviour of different cell types.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00259-014-2945-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: PET, Cell labelling, Cell tracking, 89Zr, Leukocyte labelling

Introduction

Cell tracking by scintigraphy with radionuclides has been routine in nuclear medicine for 30 years [1] for tracking autologous leukocytes to detect sites of infection/inflammation [2, 3]. The standard radiolabelling methodology has been non-specific assimilation of lipophilic, metastable complexes of 111In (with oxine [4], tropolone [5] and occasionally other bidentate chelators [6]), and later 99mTc [7].

New insight in immunology is creating interest in imaging the migration of individual immune cell types (e.g. eosinophils [8, 9], neutrophils [8, 9], T-lymphocytes [10–12], and dendritic cells [13]) in cancer, atherosclerosis, stroke, transplant and asthma. Regenerative medicine and cell-based therapies are creating new roles for tracking stem cells and chimeric antigen receptor-expressing T-lymphocytes [14, 15]. Conventional labelling methods have been applied in some of these areas, but for clinical use some of these new applications will require detection of small lesions and small numbers of cells beyond the sensitivity of gamma camera imaging with 111In (e.g. coronary artery disease, diabetes, neurovascular inflammation and thrombus), creating a need for positron-emitting radiolabels to exploit the better sensitivity, quantification and resolution of clinical positron emission tomography (PET).

So far the search for positron-emitting radiolabels for cells has met with limited success. The near-ubiquitous presence of glucose transporters allows labelling with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), but labelling efficiencies are highly variable, the radiolabel is prone to rapid efflux and the short half-life (110 min) of 18F allows only brief tracking [16–18]. 68Ga can be used to label cells [19] but it too has a short half-life (68 min). 64Cu offers a longer (12 h) half-life and efficient cell labelling using lipophilic tracers (complexes of PTSM [11, 20–22], GTSM [23], diethyldithiocarbamate [24] and tropolonate [25]), but rapid efflux of label from cells is a persistent problem and a still longer half-life would be preferred. A “PET analogue” of [111In]oxinate3, capable of cell tracking over 7 days or more, would be highly desirable but is not yet available.

89Zr is a long half-life positron emitter that could meet this need [26, 27]. The favoured oxidation state of zirconium is 4+ (compared to 3+ for indium), but the parallels between the two metals in reactivity and preferred ligand types suggest that the mechanism exploited to label cells with 111In (i.e. lipophilic metastable chelates entering cells and subsequently dissociating) might be exploited in the case of 89Zr. Tetravalent zirconium forms ZrL4 complexes with monobasic bidentate ligands such as oxinate [28], tropolonate [29] and hydroxamates [30], analogous to InL3 [31, 32]. Here we describe the first synthesis of [89Zr]oxinate4 and comparison with [111In]oxinate3 for labelling several cell lines and tracking eGFP-5T33 cells in mice. eGFP-5T33 is a syngeneic murine multiple myeloma model originating from the C57Bl/KaLwRij strain [33], engineered to express enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP). It was chosen for this work because the fate of the cells after i.v. inoculation is known from the literature [34–36] and prior work in our laboratory. Like human multiple myeloma, 5T33 develops elevated serum immunoglobulin levels and osteolytic disease [33, 37]. Intravenously injected cells migrate exclusively to the liver, spleen and bone marrow [37].

Materials and methods

Radiochemistry

89Zr was supplied as Zr4+ in a 0.1 M oxalic acid (PerkinElmer, Seer Green, UK), brought to pH 7 with 1 M Na2CO3 and diluted to 500 μl with water. This “neutralised [89Zr]oxalate” was used as a control in cell labelling experiments in vitro. To prepare [89Zr]oxinate4 the above neutralised [89Zr]oxalate solution (typically 20–90 MBq) was added to a glass reaction vessel containing 500 μl of a 1 mg/ml 8-hydroxyquinoline solution in chloroform. The vessel was shaken for 15 min and the product [89Zr]oxinate4 was recovered from the chloroform phase by evaporation, redissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 10–20 μl) and diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 1–3 ml) or cell culture medium. Full details are provided in the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM).

Cell labelling initial evaluation

[89Zr]Oxinate4 was evaluated in vitro in three cell lines: cultured J774 mouse macrophages [38], MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells [39] and eGFP-5T33 murine myeloma cells [40]; and in leukocytes from healthy volunteers. Studies were approved by an independent UK National Research Ethics Committee and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. Culture methods and leukocyte preparation and labelling are described in the ESM. Labelling of cell lines was initially evaluated as follows: To triplicate suspensions of 106 cells in 450 μl of serum-depleted [i.e. not supplemented with foetal bovine serum (FBS)] culture medium in glass tubes were added 0.05 MBq of [89Zr]oxinate4 (or neutralised [89Zr]oxalate) in 50 μl of serum-depleted medium. After incubation for up to 60 min at room temperature the tubes were centrifuged (5 min, 490 g), 450 μl of supernatant was removed and both supernatant and pellet were counted in a Wallac 1282 Compugamma Universal Gamma Counter. Pellet activity was corrected for the residual 50 μl of supernatant. Similar methods were used with higher activities (up to 40 MBq) and cell numbers (up to 5 x 107) and with [111In]oxinate3 for comparison. After these initial evaluations a standard labelling incubation period of 30 min was adopted for all subsequent biological evaluation.

Efflux of radioactivity from cells

Cells were labelled with [89Zr]oxinate4 or [111In]oxinate3 in glass tubes (106 cells and 0.05 MBq 89Zr or 0.1 MBq 111In per tube), washed three times with PBS, resuspended in culture medium (500 μl) and incubated at 37 °C. Samples taken at intervals up to 24 h were centrifuged and pellets and supernatants counted.

Cell viability

To assess the effect of [89Zr]oxinate4 on viability of eGFP-5T33 cells, samples of 1.2–1.4 × 106 cells (initially 93 % viable based on trypan blue exclusion) were radiolabelled as described above, washed and incubated in 20 ml of RPMI-1640 (supplemented with 10 % FBS, 200 U/l penicillin, 0.1 g/l streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamate) in T75 tissue culture flasks at 37 °C (5 % CO2). After 24 h, viability of these cells and of controls (treated similarly except for omission of [89Zr]oxinate4) was determined by trypan blue exclusion.

Labelling eGFP-5T33 cells for in vivo cell tracking

Cells were labelled with [111In]oxinate3 or [89Zr]oxinate4 as described above [4 × 106 and 5 × 107 eGFP-5T33 cells/tube; ca. 0.5 MBq per tube for ex vivo organ counting and up to 40 MBq per tube for PET/single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging], washed three times with PBS and resuspended in 0.2–1 ml of sterile PBS ready for inoculation. Cell viabilities were determined by trypan blue exclusion. To obtain radiolabelled cell lysates, labelled eGFP-5T33 cells were subjected to three cycles of flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen and rapid heating to 90 °C before resuspending in 200–500 μl PBS and repeatedly passing through 27- and 29-gauge needles until visibly homogeneous.

Ex vivo cell tracking of eGFP-5T33 murine multiple myeloma

Animal experiments complied with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act (UK 1986) and Home Office (UK) guidelines. Male C57Bl/KaLwRij mice, 6–7 weeks old (Harlan, UK) were acclimatised for >7 days with ad libitum access to water and diet. To assess early tissue distribution ten mice were inoculated via the tail vein with 2 × 106 cells labelled with 0.6–0.8 MBq [89Zr]oxinate4 in 100 μl sterile PBS and culled by cervical dislocation at 9 (n = 3), 24 (n = 4) and 48 h (n = 3) post-injection for ex vivo tissue counting. The longer-term biodistribution of [89Zr]oxinate4- and [111In]oxinate3-labelled cells was compared in three mice injected with 0.9 MBq [89Zr]oxinate4 in 6 × 106 cells and three with 1.7 MBq [111In]oxinate3 in 5 × 106 cells), culled by cervical dislocation after 7 days. Major thoraco-abdominal organs, the left femur and thigh muscle were excised, weighed and gamma-counted.

Ex vivo fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

Mice were culled by CO2 asphyxiation 2 (n = 3) and 7 days (n = 3) after inoculation with 107 eGFP-5T33 cells labelled with 1.5 MBq [89Zr]oxinate4. Livers, spleens and femora were harvested. Livers and spleens were homogenised. Homogenates were filtered through a 40-μm cell strainer (BD, USA), diluted to 107 cells/ml in ice-cold FACS buffer [1 v/v% FBS, 2 μM ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA) in PBS] and kept on ice. Marrow was flushed from the femora with 5–6 ml of ice-cold FACS buffer, filtered through a 40-μm cell strainer and kept on ice. Samples were analysed on a BD FACSAria III cell sorter (BD, USA) collecting 10,000 each of eGFP-positive and eGFP-negative cells (day 2) and 20,000 each of eGFP-positive and eGFP-negative cells (day 7) for gamma counting.

PET imaging

Preclinical PET/CT images were acquired in a nanoScan® PET/CT (Mediso, Budapest, Hungary) scanner with mice under isoflurane (2 % in oxygen) anaesthesia, starting 60 s before inoculation with 107 eGFP-5T33 cells labelled with 5 MBq [89Zr]oxinate4 in a 200-μl bolus via the right lateral tail vein. Scanning was continued for 2 h and repeated 1, 2, 5, 7 and 14 days after inoculation, acquiring a CT scan after each PET scan. Control mice were inoculated with [89Zr]oxinate4 (4 MBq in 100 μl saline) but no cells, and lysate from 1.1 × 106 cells labelled with 0.9 MBq [89Zr]oxinate4, and scanned between 5 and 50 min post-injection and at 24 h post-injection.

SPECT imaging

SPECT scans were acquired for 4 h immediately after inoculation of 107 eGFP-5T33 cells labelled with 10 MBq [111In]oxinate3 in a 200-μl bolus, using a nanoSPECT/CT (silver upgrade, Mediso, Budapest, Hungary) with four high-resolution multi-pinhole collimators. Further SPECT scans were acquired 1, 2, 3, 5 and 7 days post-injection, each followed by a CT scan. As a control, cell lysate from ca. 1.1 × 106 cells labelled with 1.1 MBq [111In]oxinate3 was injected intravenously followed by SPECT/CT scanning at 60 and 105 min post-injection.

Statistics

Statistical significance was tested using a two-tailed Student’s t test with significance defined as a confidence level of 95 % or above.

Results

Synthesis and quality control of [89Zr]oxinate4

A biphasic system, with the radiolabel in aqueous solution and oxine in chloroform, was used to synthesise [89Zr]oxinate4. Yields of radioactivity in the chloroform phase were ca. 60 %. Repeated extraction with further aliquots of oxine solution in chloroform led to increased yields (see ESM). Both chloroform extraction and instant thin-layer chromatography (ITLC, Rf =0.9, cf. zero for [89Zr]oxalate) before and after dilution of the DMSO solution in saline/serum-depleted RPMI-1640 reproducibly showed radiochemical purity above 99 %.

Cell labelling

Initial labelling experiments in all cell lines and leukocytes showed rapid accumulation of [89Zr]oxinate4, approaching plateau levels by 30 min (Fig. S1). In all subsequent labelling experiments a standard labelling incubation time of 30 min was adopted, leading to labelling efficiencies in the range of 40–61 % for up to 9 × 107 cells, as shown in Table 1. By contrast, uptake of neutralised [89Zr]oxalate, although increasing with time, was much lower and never exceeded 5 % (Fig. S1).

Table 1.

Cell labelling efficiencies with [89Zr]oxinate4 and [111In]oxinate3 in different cell types

| Cell number (concentration) | Labelling efficiency 89Zr | Labelling efficiency 111In | Medium | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| J774 mouse macrophages | 106 (2 × 106/ml) | 23.1 ± 1.8 (n = 3) (not optimised) | – | Cell culture medium (DMEM) |

| MDA-MB-231 breast cancer | 106 (2 × 106/ml) | 20.2 ± 3.7 (n = 3) (not optimised) | – | Cell culture medium (DMEM) |

| eGFP-5T33 mouse myeloma | <5 × 107 (<1.3 × 107/ml) | 43.2 ± 6.4 (n = 3) | 96, 82 (n = 2) | Cell culture medium (RPMI 1640) |

| Human leukocytes | 9 × 107 (4.5 × 107/ml) | 54.3 ± 11.9 (n = 3) | 46.8 ± 12.3 (n = 3) | Saline |

| 2 × 107 (107/ml) | 47.0 ± 10.5 (n = 3) | – | Saline |

Efflux from cells

Efflux of 89Zr from all three labelled cell lines in vitro was significantly slower than efflux of 111In; at 24 h, >90 % of 89Zr was retained by J774 macrophages (cf. 51.9 % for 111In), >83 % by MDA-MB-231 cells (cf. 43.7 % for 111In) and >71 % by eGFP-5T33 cells (Fig. S2). Retention of 89Zr in leukocytes after 24 h was 85.1 and 86.9 % (n = 2).

Cell viability

[89Zr]Oxinate4 labelling reduced viability of eGFP-5T33 cells from 93 % before labelling to 76.3 ± 3.2 % immediately post-labelling [cf. 89.7 ± 1.2 % (p = 0.01) for 89Zr-free controls], but there was no further significant loss in viability 24 h after labelling (87.3 ± 4.0 %, cf. 89.3 ± 3.0 % for 89Zr-free controls, n = 3).

In vivo cell tracking

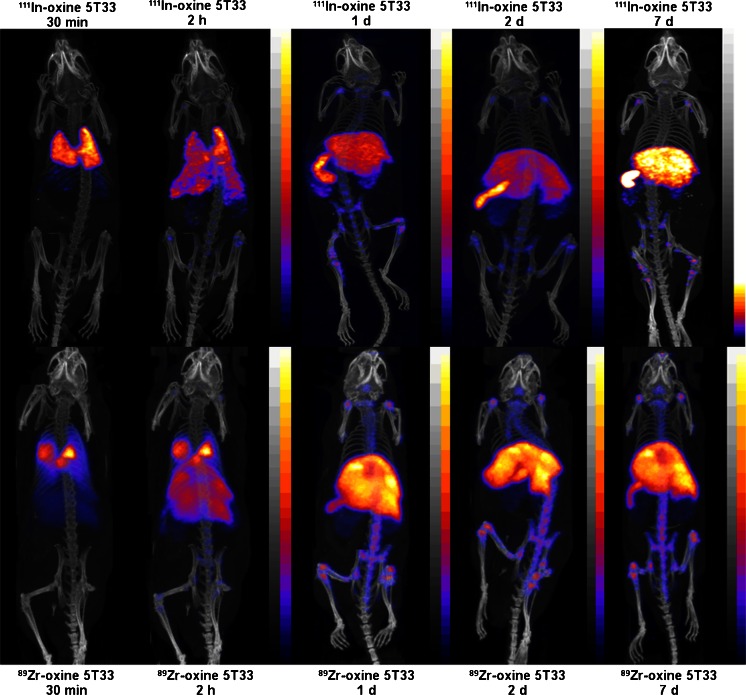

PET imaging after inoculation of [89Zr]oxinate4-labelled eGFP-5T33 myeloma cells demonstrated accumulation of cells in lungs at 30 min followed by migration to liver, spleen and bone marrow by 24 h. Ex vivo tissue sampling (Table 2 and Fig. S3) confirmed location of radioactivity predominantly in liver, spleen and bone marrow between 9 and 48 h.

Table 2.

Tissue distribution of 89Zr after i.v. inoculation of [89Zr]oxinate4-labelled eGFP-5T33 cells in C57Bl/KaLwRij mice

| Organ | 89Zr-oxine | 89Zr-oxine | 89Zr-oxine | 89Zr-oxine | 89Zr-oxine | 89Zr-oxine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 h (n = 3) | 9 h (n = 3) | 24 h (n = 4) | 24 h (n = 4) | 48 h (n = 3) | 48 h (n = 3) | |

| %ID/g | %ID | %ID/g | %ID | %ID/g | %ID | |

| Heart | 0.85 ± 0.09 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.50 ± 0.13 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.32 ± 0.07 | 0.08 ± 0.02 |

| Lungs | 2.28 ± 0.41 | 0.60 ± 0.11 | 1.35 ± 0.07 | 0.41 ± 0.04 | 0.68 ± 0.06 | 0.21 ± 0.04 |

| Liver | 44.6 ± 10.6 | 73.9 ± 6.3 | 42.2 ± 9.1 | 69.2 ± 7.5 | 30.9 ± 4.2 | 57.6 ± 5.3 |

| Spleen | 75.0 ± 13.1 | 5.8 ± 0.80 | 99.5 ± 11.0 | 6.6 ± 0.38 | 54.9 ± 1.2 | 4.7 ± 0.52 |

| Stomach | 0.29 ± 0.08 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.45 ± 0.17 | 0.16 ± 0.08 | 0.28 ± 0.07 | 0.12 ± 0.01 |

| Small int. | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.07 | 0.32 ± 0.04 |

| Large int. | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.04 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 0.29 ± 0.14 | 0.21 ± 0.04 | 0.26 ± 0.10 |

| Kidneys | 3.9 ± 0.45 | 1.8 ± 0.15 | 4.0 ± 0.44 | 1.65 ± 0.26 | 3.0 ± 0.43 | 1.42 ± 0.21 |

| Muscle | 0.19 ± 0.03 | – | 0.21 ± 0.05 | – | 0.13 ± 0.03 | – |

| Femur | 7.1 ± 1.4 | 0.63 ± 0.08 | 8.4 ± 0.47 | 0.76 ± 0.02 | 5.3 ± 0.85 | 0.52 ± 0.04 |

| Salivary gl. | 0.54 ± 0.06 | 0.12 ± 0.004 | 0.52 ± 0.14 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 0.10 ± 0.03 |

| Blood | 1.8 ± 0.18 | – | 1.0 ± 0.18 | – | 0.53 ± 0.18 | – |

| Liver:spleen | 0.60 ± 0.18 | 12.7 ± 2.1 | 0.42 ± 0.10 | 10.5 ± 1.3 | 0.56 ± 0.08 | 12.1 ± 1.7 |

| Liver:femur | 6.28 ± 1.94 | 116.8 ± 17.2 | 5.02 ± 1.12 | 91.1 ± 10.2 | 5.83 ± 1.23 | 110.8 ± 13.5 |

| Spleen:femur | 10.6 ± 2.78 | 9.2 ± 1.7 | 11.9 ± 1.47 | 8.7 ± 0.56 | 10.4 ± 1.68 | 9.1 ± 1.22 |

| Liver:kidneys | 11.4 ± 3.0 | 40.9 ± 4.8 | 10.6 ± 2.6 | 42.0 ± 8.1 | 10.3 ± 2.0 | 40.5 ± 7.1 |

| Spleen:kidneys | 19.2 ± 4.0 | 3.2 ± 0.52 | 24.9 ± 3.9 | 4.0 ± 0.67 | 18.3 ± 2.7 | 3.3 ± 0.61 |

| Femur:kidneys | 1.8 ± 0.42 | 0.35 ± 0.05 | 2.1 ± 0.26 | 0.46 ± 0.07 | 1.8 ± 0.38 | 0.37 ± 0.06 |

%ID and %ID/g were calculated after ex vivo tissue counting; mean ± SD

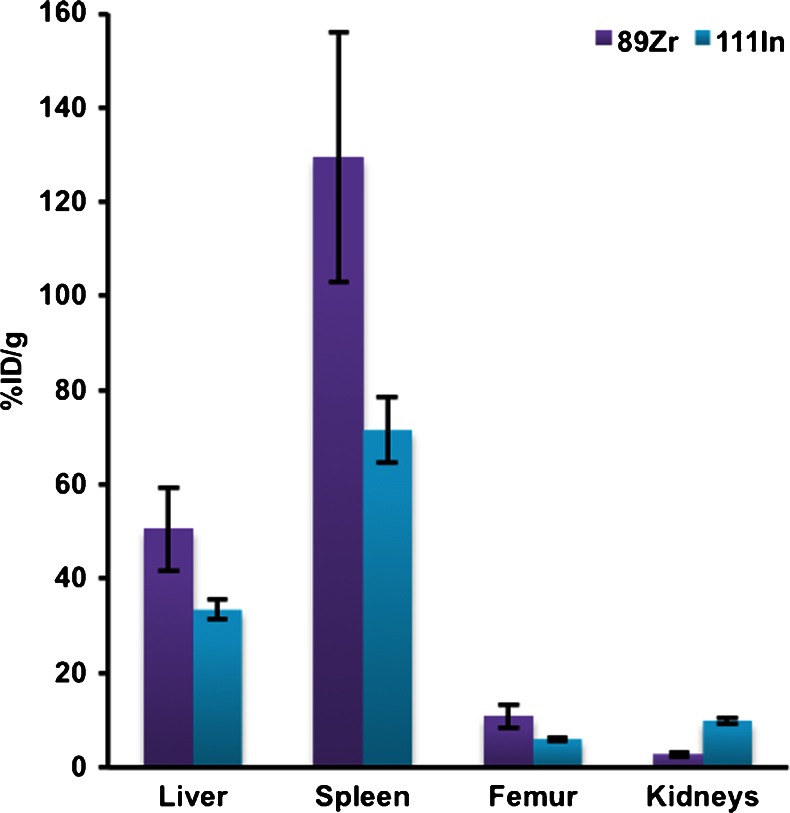

The in vivo biodistribution of 89Zr-labelled eGFP-5T33 myeloma cells was compared alongside that of cells from the same culture labelled with 111In longitudinally over 7 days using PET and SPECT imaging and ex vivo tissue sampling up to 7 days (Fig. 1, Table 3). Cell viabilities were 85–95 % with both radiolabels before inoculation. PET and SPECT images between 30 min and 7 days are shown in Fig. 2. A PET image acquired on day 14 is shown in Fig. S4 and ex vivo tissue uptake data for both radionuclides at 7 days are listed in Table 3. 111In SPECT and 89Zr PET showed qualitatively similar migration patterns in the first few hours after inoculation. However, there was significantly higher %ID/g of 89Zr than 111In in the main target organs (liver, spleen, bone) at 7 days (by factors of 1.5, 1.8 and 1.8, p = 0.03, p = 0.02 and p = 0.03, respectively) (Table 3). The %ID/g of 111In in kidneys increased with time, reaching 3.75-fold higher (p < 0.0001) than that of 89Zr by 7 days.

Fig. 1.

Radioactivity distribution 7 days after inoculation of mice with [89Zr]oxinate4- and [111In]oxinate3-labelled eGFP-5T33 cells. %ID and %ID/g were calculated after ex vivo tissue counting and are given as mean ± SD (n = 3 per group). Data are selected from Table 3 to show accumulation of 89Zr and 111In in haemopoietic tissues and kidneys (the main locations of radioactivity)

Table 3.

Radioactivity distribution 7 days after i.v. inoculation of C57Bl/KaLwRij mice with [89Zr]oxinate4- and [111In]oxinate3-labelled eGFP-5T33 cells

| Organ | 89Zr-oxine | 89Zr-oxine | 111In-oxine | 111In-oxine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 days (n = 3) | 7 days (n = 3) | 7 days (n = 3) | 7 days (n = 3) | |

| %ID/g | %ID | %ID/g | %ID | |

| Heart | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 0.03 ± 0.005 | 0.71 ± 0.12 | 0.12 ± 0.02 |

| Lungs | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 0.09 ± 0.009 | 0.66 ± 0.05 | 0.20 ± 0.009 |

| Liver | 50.6 ± 8.9 | 58.2 ± 5.5 | 33.4 ± 2.1 | 43.8 ± 3.1 |

| Spleen | 129.5 ± 26.5 | 7.9 ± 0.76 | 71.6 ± 6.9 | 4.59 ± 0.34 |

| Stomach | 0.43 ± 0.12 | 0.12 ± 0.06 | 0.66 ± 0.14 | 0.19 ± 0.03 |

| Small int. | 0.17 ± 0.07 | 0.16 ± 0.06 | 0.43 ± 0.11 | 0.44 ± 0.12 |

| Large int. | 0.17 ± 0.08 | 0.18 ± 0.09 | 0.45 ± 0.07 | 0.58 ± 0.16 |

| Kidneys | 2.64 ± 0.39 | 0.96 ± 0.06 | 9.9 ± 0.64 | 4.2 ± 0.39 |

| Muscle | 0.16 ± 0.02 | – | 0.43 ± 0.05 | – |

| Femur | 10.8 ± 2.5 | 0.88 ± 0.12 | 6.0 ± 0.5 | 0.56 ± 0.04 |

| Salivary gl. | 0.40 ± 0.03 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 1.96 ± 0.24 | 0.35 ± 0.08 |

| Blood | 0.23 ± 0.1 | – | 0.22 ± 0.06 | – |

| Liver:spleen | 0.39 ± 0.11 | 7.3 ± 1.0 | 0.47 ± 0.05 | 9.5 ± 1.0 |

| Liver:femur | 4.69 ± 1.36 | 66.0 ± 11.2 | 5.57 ± 0.58 | 78.7 ± 8.4 |

| Spleen:femur | 12.0 ± 3.71 | 9.0 ± 1.5 | 11.9 ± 1.52 | 8.3 ± 0.9 |

| Liver:kidneys | 19.2 ± 4.4 | 60.6 ± 6.7 | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 10.5 ± 1.25 |

| Spleen:kidneys | 49.1 ± 12.4 | 8.3 ± 0.92 | 7.23 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.13 |

| Femur:kidneys | 4.1 ± 1.1 | 0.92 ± 0.14 | 0.61 ± 0.06 | 0.13 ± 0.02 |

%ID and %ID/g were calculated after ex vivo tissue counting and are given as mean ± SD (n = 3 per group)

Fig. 2.

PET/CT and SPECT/CT images of C57Bl/KaLwRij mice inoculated with [89Zr]oxinate4- or [111In]oxinate3-labelled eGFP-5T33 cells. Scans of 111In (top) and 89Zr (bottom) are reported from 30 min to 7 days after i.v. inoculation of C57Bl/KaLwRij mice with 107 eGFP-5T33 cells labelled with 5 MBq [89Zr]oxinate4 or 10 MBq [111In]oxinate3. Image scales were adjusted to the maximum activity concentration within each image except for the 2-h images where the activity scale was adjusted to the maximum activity per voxel used in the 30-min image in order to quantitatively visualise the rapid change in the early homing pattern of eGFP-5T33 cells after i.v. inoculation

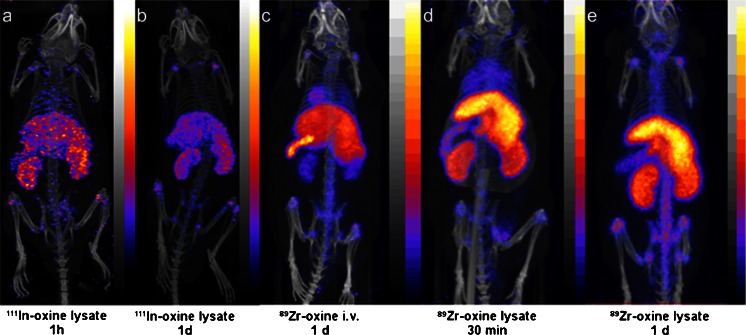

When radiolabelled cell lysates were injected i.v., uptake in the liver, spleen and skeleton was observed but there was also a much more marked accumulation in the kidneys, both for 111In and 89Zr (Fig. 3). Intravenously injected [89Zr]oxinate4 gave a qualitatively similar biodistribution to labelled cell lysates but there was also significant uptake in the heart and lungs after 24 h.

Fig. 3.

SPECT/CT and PET/CT images of mice injected with radiolabelled eGFP-5T33 cell lysates or [89Zr]oxinate4. a, b SPECT/CT images of mice injected with lysates of 1.1 × 106 eGFP-5T33 cells labelled with 1.1 MBq [111In]oxinate3 at 1 and 24 h post-injection, respectively. c PET/CT image of mouse 24 h after injection with 4 MBq [89Zr]oxinate4. d, e PET/CT images of mice injected with lysates of 1.1 × 106 eGFP-5T33 cells labelled with 0.9 MBq [89Zr]oxinate4 at 1 and 24 h post-injection, respectively

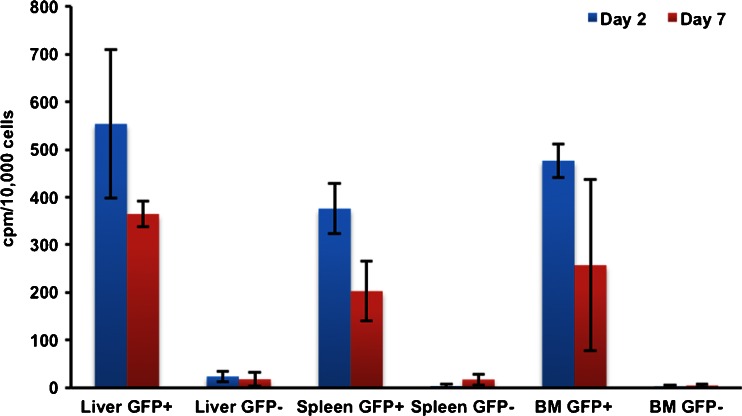

FACS sorting (based on eGFP fluorescence) of organ homogenates from animals culled 2 and 7 days after inoculation with cells labelled with [89Zr]oxinate4 showed that the eGFP-positive cells contained more activity per cell (by a factor of >23 at 2 days and a factor of >12 at 7 days) than eGFP-negative cells (p < 0.02) (Fig. 4). Example FACS data are reported in Fig. S5.

Fig. 4.

89Zr activities in eGFP-positive and eGFP-negative cell populations sorted from organ samples. Liver, spleen and femoral marrow (BM) organ homogenates were harvested from mice 2 and 7 days after i.v. inoculation with [89Zr]oxinate4-labelled eGFP-5T33 cells (n = 3/group, decay corrected)

Discussion

A general-purpose radiolabel that allows the advantages of PET to be implemented for tracking cells in vivo over several days should satisfy several criteria: the radioisotope must have a suitably long half-life and appropriate positron energy and abundance, convenient and economic availability, a simple and efficient labelling procedure, no major selectivity for different cell types, minimal effects on cell survival and function in vivo and minimal efflux from cells. These criteria should be met at least as well as [111In]oxinate3 meets them and better than positron-emitting alternatives reported to date. We have synthesised a lipophilic, metastable complex, [89Zr]oxinate4, evaluated it biologically in a range of cell lines in vitro and selected one cell line (eGFP-5T33 myeloma cells) for evaluation in vivo. The results indicate that [89Zr]oxinate4 meets these criteria. The half-life of 89Zr is 3.3 days (longer than that of 111In and potential positron-emitting competitors 64Cu, 18F and 68Ga); only 124I (4.2 days) is comparable in this respect but cell labelling with 124I has not been reported. The positron abundance and energies and gamma emissions of 89Zr, although not ideal compared to 18F, 64Cu and 68Ga, proved adequate to give better-resolved images than SPECT with 99mTc in a direct comparison (human sentinel node imaging) [41]. 89Zr is now commercially and economically available as a GMP product. The cell labelling procedure described here is simple, indeed identical to that used with [111In]oxinate3; good labelling efficiencies are achieved within a few minutes. The labelling method is effective for several different cell lines and human leukocytes. The survival of labelled eGFP-5T33 cells in vitro is comparable to or better than that of [111In]oxinate3-labelled cells and not significantly different to that of control cells treated identically except for omission of radioactivity. While leukocytes are efficiently labelled and show good retention of radioactivity at 24 h, the effects of labelling on survival and function have not been determined, and further investigation of these aspects in the different leukocyte types are required. The in vivo biodistribution and FACS sorting data suggest that labelled eGFP-5T33 cells remain viable for at least 7 days, since the 89Zr-labelled cells continue to express eGFP after this period in vivo. Retention of 89Zr by cells studied here in vitro over 24 h compares well with published cell radiolabels; it is significantly better than that of 111In and markedly superior to that of cells labelled with 64Cu complexes of PTSM [11, 20–22] and GTSM [23] or with 18F-FDG. The superior retention of 89Zr compared to 111In by eGFP-5T33 cells in vivo is inferred from the much slower transfer of 89Zr than 111In from liver, spleen and bone marrow to kidneys and suggests that replacing 111In SPECT with 89Zr PET can extend the period over which cells can be reliably tracked in vivo; indeed, we have been able to acquire good PET images up to 2 weeks post-inoculation. The 14-day image showed a similar biodistribution of radioactivity to that seen at 7 days in the same mouse suggesting that the radiolabel continued to be retained by 5T33 cells in vivo (Fig. S4).

The overall biodistribution observed with both 111In- and 89Zr-labelled cells (initial uptake in lung followed by migration to liver, spleen and bone marrow) is consistent with earlier studies of the migration of related murine myeloma cells, by histology and by radiolabelling with 51Cr [35]. Organ to organ uptake ratios among the main target organs (liver, spleen, bone marrow) did not vary significantly throughout the study, either for 89Zr or 111In, suggesting that labelled cells, or radioactivity, did not migrate from one haematopoietic tissue to another and that the radiolabel used did not change the tissue preference of eGFP-5T33 cells. To test the implicit assumption that migration of radioactivity from liver, spleen and bone marrow to kidney and bladder is an indicator of gradual efflux of radioactivity from living or dead labelled cells, we examined the distribution of activity after injection of [89Zr]oxinate4 and that of cells that had been killed/lysed after radiolabelling with 89Zr and 111In. The resulting biodistribution qualitatively resembled that seen with labelled healthy cells, but both 89Zr- and 111In-labelled cell lysate showed greatly increased uptake in kidney and also liver and reduced uptake in spleen, even at early time points (30 min, 24 h, Fig. 3), compared to labelled healthy cells. This contrast in behaviour of 89Zr injected in the form of living labelled cells and dead/lysed labelled cells is consistent with the hypothesis that migration of radioactivity from initially targeted organs to kidney and bladder is a non-invasive marker for efflux of radioactivity from living or dying labelled cells in vivo.

89Zr injected in the form of neutralised [89Zr]-oxalate also shows marked differences from the behaviour of labelled cells, consistent with the assumption that the images obtained after injection of 89Zr-labelled cells reflect the location of the cells. With [89Zr]oxinate4 significant uptake in heart was observed that was not seen with labelled cells, while [89Zr]oxalate shows gradual skeletal accumulation: radioactivity can be imaged in the joints as early as 15 min post-injection [42, 43].

The novel experimental approach of ex vivo FACS sorting of eGFP-positive and eGFP-negative populations from organ homogenates, followed by radiation counting of these fractions, showed that the radioactivity in the target tissues remains associated with the originally labelled eGFP-expressing cells (Fig. 4), and hence that these labelled cells remain alive during the 7 days in vivo; 96 % of liver radioactivity, 99 % of spleen radioactivity and >99 % of bone marrow radioactivity remains associated with eGFP-positive cells at 2 days, falling to 95, 92 and 98 %, respectively, by 7 days. Although we observed excellent in vivo survival of labelled eGFP-5T33 cells in this study, a more thorough understanding of the possible cytotoxic effects of the wider use of both 89Zr and 111In labelling of cells is required for a proper interpretation of cell tracking data generally. This ex vivo FACS-based method provides a potential experimental approach to this challenging problem.

These highly promising results warrant further development including refinement of the radiosynthesis and labelling process to improve radiochemical and cell labelling yields, select the most suitable medium for cell labelling and eliminate undesirable use of chloroform, and determine the functional and survival effects of labelling in a variety of cell types, prior to evaluation of the method for cell tracking in humans. While estimates of likely dosimetry in humans have not yet been performed, it will also be important to assess the potential advantages of cell tracking by PET with 89Zr against the likely increased radiation burden per megabecquerel associated with 89Zr, balancing the increased dose per decay, the low positron yield of 89Zr and the increased detection efficiency of PET compared to SPECT.

Conclusion

The new lipophilic, metastable complex of 89Zr can radiolabel a range of cells, independently of specific phenotypes, providing a long-sought solution to the unmet need for a long half-life positron-emitting radiolabel to replace 111In for cell migration imaging. In addition to the expected advantages (enhanced sensitivity, resolution and quantification) of cell tracking with PET rather than scintigraphy or SPECT, 89Zr shows less efflux from eGFP-5T33 cells in vitro and in vivo than 111In during at least 7 days after labelling. The excellent in vivo survival and retention of radioactivity by the cells at 7 days, coupled with the demonstrated ability to acquire useful PET images up to 14 days, significantly extend the typical period over which cells can be tracked by radionuclide imaging with directly labelled cells. This method offers a potential solution to the emerging need for a long half-life PET tracer for cell tracking in vivo and deserves further evaluation of its effects on survival and behaviour of different cell types, and the dosimetric and radiobiological implications of application in humans.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PDF 649 kb)

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Leukaemia and Lymphoma Research, the Centre of Excellence in Medical Engineering Centre funded by the Wellcome Trust and EPSRC (WT088641/Z/09/Z), the King’s College London and UCL Comprehensive Cancer Imaging Centre funded by the CRUK and EPSRC in association with the MRC and DoH (England), and by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. PC was supported by a scholarship from Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the DoH. PET and SPECT scanning equipment was funded by an equipment grant from the Wellcome Trust.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Footnotes

Putthiporn Charoenphun and Levente K. Meszaros contributed equally to this work and are joint first authors.

References

- 1.Segal AW, Arnot RN, Thakur ML, Lavender JP. Indium-111-labelled leucocytes for localisation of abscesses. Lancet. 1976;2:1056–1058. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(76)90969-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters AM. A brief history of cell labelling. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;49:304–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basu S, Zhuang HM, Torigian DA, Rosenbaum J, Chen WG, Alavi A. Functional imaging of inflammatory diseases using nuclear medicine techniques. Semin Nucl Med. 2009;39:124–145. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Intenzo CM, Desai AG, Thakur ML, Park CH. Comparison of leukocytes labeled with indium-111-2-mercaptopyridine-N-oxide and indium-111 oxine for abscess detection. J Nucl Med. 1987;28:438–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotzé HF, Heyns AD, Lötter MG, Pieters H, Roodt JP, Sweetlove MA, et al. Comparison of oxine and tropolone methods for labeling human platelets with indium-111. J Nucl Med. 1991;32:62–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellis BL, Sampson CB, Abeysinghe RD, Porter JB, Hider RC. 6-Alkoxymethyl-3-hydroxy-4H-pyranones: potential ligands for cell-labelling with indium. Eur J Nucl Med. 1999;26:1400–1406. doi: 10.1007/s002590050471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters AM. The utility of [99mTc]HMPAO-leukocytes for imaging infection. Semin Nucl Med 1994;24:110–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Puncher MRB, Blower PJ. Autoradiography and density gradient separation of technetium-99m-exametazime (HMPAO) labelled leucocytes reveals selectivity for eosinophils. Eur J Nucl Med. 1994;21:1175–1182. doi: 10.1007/BF00182350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lukawska JJ, Livieratos L, Sawyer BM, Lee T, O’Doherty M, Blower PJ, et al. Real-time differential tracking of human neutrophil and eosinophil migration in vivo. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharif-Paghaleh E, Sunassee K, Tavaré R, Ratnasothy K, Koers A, Ali N, et al. In vivo SPECT reporter gene imaging of regulatory T cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griessinger CM, Kehlbach R, Bukala D, Wiehr S, Bantleon R, Cay F, et al. In vivo tracking of Th1 cells by PET reveals quantitative and temporal distribution and specific homing in lymphatic tissue. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:301–307. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.126318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruparelia P, Szczepura KR, Summers C, Solanki CK, Balan K, Newbold P, et al. Quantification of neutrophil migration into the lungs of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:911–919. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1715-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tavaré R, Sagoo P, Varama G, Tanriver Y, Warely A, Diebold SS, et al. Monitoring of in vivo function of superparamagnetic iron oxide labelled murine dendritic cells during anti-tumour vaccination. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leech JM, Sharif-Paghaleh E, Maher J, Livieratos L, Lechler RI, Mullen GE, et al. Whole-body imaging of adoptively transferred T cells using magnetic resonance imaging, single photon emission computed tomography and positron emission tomography techniques, with a focus on regulatory T cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2013;172:169–177. doi: 10.1111/cei.12087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zanzonico P, Koehne G, Gallardo HF, Doubrovin M, Doubrovina E, Finn R, et al. [131I]FIAU labeling of genetically transduced, tumor-reactive lymphocytes: cell-level dosimetry and dose-dependent toxicity. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2006;33:988–97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Elhami E, Goertzen AL, Xiang B, Deng JX, Stillwell C, Mzengeza S, et al. Viability and proliferation potential of adipose-derived stem cells following labeling with a positron-emitting radiotracer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:1323–1334. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1753-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forstrom LA, Mullan BP, Hung JC, Lowe VJ, Thorson LM. 18F-FDG labelling of human leukocytes. Nucl Med Commun 2000;21:691–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Stojanov K, de Vries EFJ, Hoekstra D, van Waarde A, Dierckx R, Zuhorn IS. [18F]FDG labeling of neural stem cells for in vivo cell tracking with positron emission tomography: inhibition of tracer release by phloretin. Mol Imaging 2012;11:1–12. [PubMed]

- 19.Welch MJ, Thakur ML, Coleman RE, Patel M, Siegel BA, Terpogossian MM. Gallium-68 labeled red cells and platelets: new agents for positron tomography. J Nucl Med. 1977;18:558–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang J, Lee CCI, Sutcliffe JL, Cherry SR, Tarantal AF. Radiolabeling rhesus monkey CD34(+) hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells with 64Cu-pyruvaldehyde-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) for microPET imaging. Mol Imaging 2008;7:1–11. [PubMed]

- 21.Park JJ, Lee TS, Son JJ, Chun KS, Song IH, Park YS, et al. Comparison of cell-labeling methods with 124I-FIAU and 64Cu-PTSM for cell tracking using chronic myelogenous leukemia cells expressing HSV1-tk and firefly luciferase. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2012;27:719–728. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2012.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adonai N, Nguyen KN, Walsh J, Iyer M, Toyokuni T, Phelps ME, et al. Ex vivo cell labeling with 64Cu-pyruvaldehyde-bis(N-4-methylthiosemicarbazone) for imaging cell trafficking in mice with positron-emission tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3030–3035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052709599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charoenphun P, Paul R, Weeks A, Berry D, Shaw K, Mullen G, et al. PET tracers for cell labelling with the complexes of copper 64 with lipophilic ligands. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:S294. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li ZB, Chen K, Wu ZH, Wang H, Niu G, Chen XY. 64Cu-labeled PEGylated polyethylenimine for cell trafficking and tumor imaging. Mol Imaging Biol. 2009;11:415–423. doi: 10.1007/s11307-009-0228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhargava KK, Gupta RK, Nichols KJ, Palestro CJ. In vitro human leukocyte labeling with 64Cu: an intraindividual comparison with 111In-oxine and 18F-FDG. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36:545–549. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meszaros LK, Charoenphun P, Chuamsaamarkkee K, Ballinger JR, Mullen G, Ferris TJ, et al. 89Zr-Oxine complex: a long-lived radiolabel for cell tracking using PET. 2013 World Molecular Imaging Congress. http://www.wmis.org/abstracts/2013/data/index.htm. Accessed 15 June 2014.

- 27.Ferris T, Charoenphun P, Went M, Blower P. Medical imaging utilising zirconium complexes (abstract) Nucl Med Commun. 2013;34:362–411. doi: 10.1097/01.mnm.0000427745.93442.b4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kathirgamanathan P, Surendrakumar S, Antipan-Lara J, Ravichandran S, Reddy VR, Ganeshamurugan S, et al. Discovery of two new phases of zirconium tetrakis(8-hydroxyquinolinolate): synthesis, crystal structure and their electron transporting characteristics in organic light emitting diodes (OLEDs) J Mater Chem. 2011;21:1762–1771. doi: 10.1039/c0jm02644a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muetterties EL, Algeranti CW. Chelate chemistry. VI. Solution behavior of tropolonates. J Am Chem Soc. 1969;91:4420–4425. doi: 10.1021/ja01044a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guérard F, Lee YS, Tripier R, Szajek LP, Deschamps JR, Brechbiel MW. Investigation of Zr(IV) and 89Zr(IV) complexation with hydroxamates: progress towards designing a better chelator than desferrioxamine B for immuno-PET imaging. Chem Commun 2013;49:1002–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Nepveu F, Jasanada F, Walz L. Structural characterization of two lipophilic tris(tropolonato) gallium(III) and indium(III) complexes of radiopharmaceutical interest. Inorg Chim Acta 1993;211:141–7.

- 32.Abrahams I, Choi N, Henrick K, Joyce H, Matthews RW, McPartlin M, et al. The crystal and molecular-structures of the blood-cell labeling agents tris(2-hydroxy-2,4,6-cycloheptatrien-1-onato-O,O′)indium(III) and trans-(tris(4-iso-propyl-2-hydroxy-2,4,6-cycloheptatrien-1-onato-O,O′) indium(III)) Polyhedron. 1994;13:513–516. doi: 10.1016/S0277-5387(00)81668-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radl J, Croese JW, Zurcher C, Van den Enden-Vieveen MHM, de Leeuw AM. Animal model of human disease. Multiple myeloma. Am J Pathol. 1988;132:593–597. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanderkerken K, Asosingh K, Croucher P, Van Camp B. Multiple myeloma biology: lessons from the 5TMM models. Immunol Rev. 2003;194:196–206. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065X.2003.00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vanderkerken K, De Greef C, Asosingh K, Arteta B, De Veerman M, Vande Broek I, et al. Selective initial in vivo homing pattern of 5T2 multiple myeloma cells in the C57BL/KalwRij mouse. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:953–959. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vanderkerken K, De Raeve H, Goes E, Van Meirvenne S, Radl J, Van Riet I, et al. Organ involvement and phenotypic adhesion profile of 5T2 and 5T33 myeloma cells in the C57BL/KaLwRij mouse. Br J Cancer. 1997;76:451–460. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garrett IR, Dallas S, Radl J, Mundy GR. A murine model of human myeloma bone disease. Bone. 1997;20:515–520. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(97)00056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Snyderman R, Pike MC, Fischer DG, Koren HS. Biologic and biochemical activities of continuous macrophage cell lines P388D1 and J774.1. J Immunol. 1977;119:2060–2066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cailleau R, Olivé M, Cruciger QV. Long-term human breast carcinoma cell lines of metastatic origin: preliminary characterization. In Vitro. 1978;14:911–915. doi: 10.1007/BF02616120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alici E, Konstantinidis KV, Aints A, Dilber MS, Abedi-Valugerdi M. Visualization of 5T33 myeloma cells in the C57BL/KaLwRij mouse: establishment of a new syngeneic murine model of multiple myeloma. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:1064–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heuveling DA, van Schie A, Vugts DJ, Hendrikse NH, Yaqub M, Hoekstra OS, et al. Pilot study on the feasibility of PET/CT lymphoscintigraphy with 89Zr-nanocolloidal albumin for sentinel node identification in oral cancer patients. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:585–589. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.115188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abou DS, Ku T, Smith-Jones PM. In vivo biodistribution and accumulation of 89Zr in mice. Nucl Med Biol. 2011;38:675–681. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma MT, Meszaros L, Berry DJ, Cooper M, Clark SJ, Ballinger JR, et al. A tripodal tris(hydroxypyridinone) ligand for immunoconjugate PET imaging with zirconium-89. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2014;19:S649. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 649 kb)