Abstract

Introduction

Policy decisions related to orphan and ultra-orphan drugs challenge traditional decision-making processes and often frustrate those affected by them. In general, these drugs are associated with significant uncertainties around clinical benefit, ‘value for money’, affordability, and ‘adoption/diffusion’, all of which arise from a lack of available high-quality evidence. Increasingly, patients with rare diseases and their families are looking for opportunities to contribute to initiatives aimed at reducing these uncertainties. Therefore, a policy framework for guiding their involvement is needed to optimize the impact of any evidence generated.

Objectives

The aims of this study were (1) to explore opportunities for patient involvement in reducing decision uncertainties throughout the lifecycle of orphan and ultra-orphan drugs from the perspectives of patients within the Canadian rare disease community; and (2) to develop a policy framework for patient input that maximizes the impact of their involvement on decision uncertainties around orphan and ultra-orphan drugs.

Methods

Two one-day conferences and four workshops involving patients and/or families from rare disease communities in Canada were held to discuss issues around orphan and ultra-orphan drug development, access, and coverage, and identify opportunities for patient input to reduce related decision uncertainties. Their feedback and the findings from a recent literature review on patient involvement in rare diseases were combined into a draft policy framework based upon Kingdon’s multiple streams model of decision making. The framework was presented to a group of patients and other stakeholders, including providers, pharmaceutical drug plan managers, and industry representatives, and then revised accordingly.

Results

Patients and family members/caregivers identified tangible ways of contributing to the generation of information at all stages of the drug lifecycle. However, the proximity of that information to the reduction of a specific decision uncertainty varied. While the scope of possible ways mentioned was less broad when compared with the findings of the literature review, the focus was similar—capturing the clinical benefit of an orphan or ultra-orphan drug. A policy framework comprising three stages, each with a key question and corresponding set of sub-questions to be asked by patients, was developed. The three main sequential questions were as follows. (1) What uncertainties need to be addressed? (2) What roles should patients play? (3) Is each role feasible?

Conclusions

Reducing decision uncertainties around orphan and ultra-orphan drugs requires a policy framework that explicates when and what type of information needs to be generated, and recognizes the role of patients as important sources of such information throughout the lifecycle of these drugs.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| The challenges involved in making decisions that affect access to orphan and ultra-orphan drugs largely stem from considerable uncertainties around clinical benefit, ‘value for money’, affordability, and adoption/diffusion. |

| Based on findings from workshops, Canadian patients and families within rare disease communities are keen to contribute to initiatives aimed at reducing these uncertainties, particularly those related to clinical benefit. |

| The Kingdon multiple streams model of decision making may offer a foundation for constructing a policy framework that aims to ensure the usefulness of patient input throughout the lifecycle of orphan and ultra-orphan drugs. |

Introduction

Compared with common diseases, rare diseases tend to be more heterogeneous and involve multiple organs/systems within the body [1]. Often, their natural history and progression are not well understood, and knowledge and expertise in their management among the general medical community is limited. These factors, coupled with their low prevalence, challenge traditionally accepted methods of assessing the efficacy/effectiveness of therapies for rare diseases (e.g., orphan and ultra-orphan drugs) and, in turn, the evidence expectations of decision makers involved in determining access to them.

Compared with common diseases, the annual per-patient costs of most orphan and ultra-orphan drugs are significantly greater [2]. They are also life-long. Although the number of patients requiring access to any single drug may be few and the budget impact small, there are thousands of rare diseases and, collectively, many promising new therapies in development. Increasingly, these therapies represent disease-modifying treatments for rare diseases in which current management comprises only supportive care. Therefore, unmet needs are high, as are uncertainties in (1) clinical benefit, (2) ‘value for money’, (3) affordability, and (4) adoption/diffusion of treatments.

Given growing concerns over healthcare system sustainability, there is heightened interest in approaches to minimizing the ‘risk’ of making wrong decisions on new health services (including orphan and ultra-orphan drugs), which lead to wasted healthcare resources and poorer patient outcomes. Uncertainty drives risk, and arises from a lack of information to address questions related to factors such as clinical benefit. Thus, approaches to ensuring that the right information is collected and available in time to support decisions are needed.

Patients and families within rare disease communities have become recognized as key contributors to the development of policies throughout the lifecycle of orphan and ultra-orphan drugs. Highly motivated and experts in their disease, they represent an important identifiable source of information about a disease, its impact, and what it might take to lessen its burden on patients, families, and communities. A recent international review of patient involvement in rare diseases demonstrates the broad range of activities in which patients, families, and patient organizations are already engaged [3].

To optimize the role of those activities within the context of reducing decision uncertainties, a policy framework for guiding their conceptualization is needed. A comprehensive search for such a framework revealed none within the academic or grey literature.

Objectives

This project aimed to:

Explore opportunities for patient involvement in reducing decision uncertainties throughout the lifecycle of orphan and ultra-orphan drugs from the perspectives of patients within the Canadian rare disease community

Develop a policy framework for patient input that maximizes the impact of their involvement on decision uncertainties around orphan and ultra-orphan drugs

Methods

This paper builds upon work presented in a companion paper, describing an inventory of proposed and existing opportunities for patient input into issues specific to rare diseases and their management [3]. To explore how those opportunities could provide information to support decisions affecting access to orphan and ultra-orphan drugs, they were mapped onto a technology lifecycle–decision uncertainty matrix. The lifecycle of any technology, including drugs, comprises six main stages: (1) pre-clinical, (2) clinical trials, (3) regulatory approval, (4) post-marketing studies, (5) reimbursement, and (6) use in clinical practice. In each stage, evidence that may directly or indirectly address uncertainties in coverage decision making is generated. There are four main types of uncertainties: (1) clinical benefit, (2) ‘value for money’, (3) affordability, and (4) adoption/diffusion. Thus, the matrix offers a structured approach to linking evidence emerging from each stage, of which one type is patient input, to a particular decision uncertainty.

In this paper, the technology lifecycle–decision uncertainty matrix served as the basis for discussions with patients and families from rare disease communities around opportunities to contribute to the generation of evidence that reduces ‘risk’ in coverage decisions on orphan and ultra-orphan drugs.

Exploration of the Preferences of the Canadian Rare Disease Patient Communities Around These Opportunities

The preferences of patients and families around their involvement in activities that could generate information to reduce decision uncertainties were elicited through a multi-phased approach. Two national one-day conferences and four workshops (two national and two regional) hosted by the Canadian Organization for Rare Disorders (CORD) were held. All of these events brought together patients and families living with rare disorders in Canada (informally defined in Canada as a prevalence of <1 in 2,000) and patient organizations representing them. Participants were those who responded to an open invitation by CORD. To increase accessibility to events by all interested patients and families, travel and accommodations were provided, where needed.

One-Day Conference #1

The first one-day conference was intended to provide an overview of the environment within which rare diseases are currently managed, comparing Canadian experiences with those in the United States and Europe. International and local experts representing industry, healthcare providers, regulators, and payers offered their perspectives on challenges related to orphan and ultra-orphan drugs. The presentations were followed by small group sessions with participants from patient communities (N = 60), who were asked to discuss the goals of an ‘ideal’ process for managing the development and introduction of new therapies. Within each group, participants appointed rapporteurs, who recorded ideas on flip charts. Groups then reconvened to share their findings and obtain feedback from presenters and other non-patient stakeholders attending the conference. An overarching theme of “sustainable access to effective therapies” emerged. The conference ended with a discussion around what it might take to achieve such a goal. It centred on evidence and the need for ongoing collection of different types of data throughout the lifecycle of a drug to support the value proposition.

One-Day Conference #2

The second conference, held 4 months later, used the findings from the first conference to focus on evidence expectations of regulators and payers. Participants included patients and families, clinical specialists in rare diseases, and representatives from industry, Health Canada (federal regulatory body), and the provincial governments (payers). Of the patient participants (N = 69), most had attended the first conference. Those who hadn’t comprised ‘seasoned’ patients and family members who were already familiar with the issues around orphan and ultra-orphan drugs. Therefore, all patient participants were considered ‘informed’ members of the rare-disease patient community. The conference began with presentations on approaches to addressing existing knowledge gaps related to the screening, diagnosis, natural history, and progression of rare diseases; the meaningfulness of outcome measures (including patient-reported outcomes [PROs]); the appropriateness of clinical trial designs for assessing the efficacy of new therapies; and the use of patient registries for monitoring clinical benefit in routine clinical practice. The technology lifecycle–decision uncertainty matrix was then introduced as a way of systematically considering the outcomes of different knowledge-producing initiatives, such as those described in the presentations, within the context of different decision uncertainties. Participants were subsequently assigned to small groups comprising representatives from different stakeholder communities. Groups were ‘mixed’ to ensure participants heard multiple perspectives before arriving at shared responses. Each group completed a common exercise, which involved mapping the information discussed in the presentations during the first half of the day onto the technology lifecycle–decision uncertainty matrix. They identified how those initiatives were already or could be used to address specific uncertainties and during which stages in the technology lifecycle they applied. Groups also identified remaining gaps once all of the initiatives had been taken into account. Similar to the first conference, each small group appointed a rapporteur to report back during a plenary session. In general, groups placed initiatives in the same ‘cells’ of the matrix. ‘Disease-based patient registries’ spanned multiple ‘cells’ and became the focus of end-of-day discussions.

Therefore, the two one-day conferences, collectively, provided an opportunity for patients and families to broaden their understanding of issues around orphan and ultra-orphan drugs and engage in follow-up discussions as ‘informed’ representatives of rare-disease communities.

First Two Workshops

Two half-day workshops followed the second one-day conference, and involved only patients and families. Those who attended the conference were invited to participate. The purpose of both workshops, each of which included 15 participants, was to explore roles specifically for patients, families, and patient organizations in reducing decision uncertainties throughout the technology lifecycle. Both workshops were facilitated by the same two experienced researchers. They began with a review of the technology lifecycle–decision uncertainty matrix. Then, participants were asked about potential ways in which patients and families could contribute to the generation of evidence corresponding to each ‘cell’ of the matrix. ‘Cells’ were considered by type of decision uncertainty. For example, participants proposed opportunities for their involvement in reducing uncertainties in ‘clinical benefit’ of a new orphan or ultra-orphan drug during each chronological stage of the technology lifecycle before exploring patient input into ‘value for money’. To aid discussions, questions related to each type of uncertainty were presented (Appendix 1). They came from a recent review of decision factors/criteria used by centralized drug reimbursement review processes in the top 22 OECD countries by GDP [4]. Both workshops were audiotaped and transcribed.

Each workshop resulted in a single patient input-populated matrix. The two matrices were merged and compared with that in the companion paper, which originated from an international review of patient input around rare diseases [3]. A final matrix that combined opportunities/activities identified in the companion paper with those emerging from the workshops was then prepared.

Second Two Workshops

Opportunities/activities appearing in the final matrix were prioritized by patients and families during two regional workshops, one in Eastern Canada (Toronto) and one in Western Canada (Vancouver). Since both took place alongside CORD regional fora, all patients and families attending the fora were invited to participate in the workshops (Toronto: n = 23; Vancouver: n = 18). None had been involved in the previous sessions. Therefore, each workshop began with a summary of the purpose of the matrix and the steps that led to its development. Facilitators explained that the range of opportunities/activities comprising the matrix is broad, and it would be unreasonable to expect any single rare-disease patient community to be engaged in all of them. Thus, there is a need for patient communities to set priorities. They then asked participants to examine the opportunities/activities contained in each cell and identify their top priorities (i.e., ways of being involved that they felt were most important, as well as feasible). Participants could identify any number of opportunities/activities as priorities. They were also asked to consider the extent to which a single opportunity/activity could produce information that addressed multiple decision uncertainties, either directly or indirectly. To facilitate these discussions, the same set of questions as that used in the first two workshops were presented (Appendix 1). Once again, both workshops were audiotaped and transcribed.

The outputs of these two workshops were two populated matrices of patient-prioritized opportunities for input along the lifecycle of an orphan or ultra-orphan drug.

To develop an in-depth understanding of how participants in the four workshops arrived at their decisions, transcripts from all four workshops were analysed qualitatively using a general inductive approach [5, 6]. This approach is often employed in research that aims to develop models of the underlying structure of perspectives or experiences. Two researchers first read through all of the transcripts and developed initial coding categories, which represented potential themes. Chunks of text were then assigned to one or more of these categories. Sub-categories were created when sub-themes emerged. Examples of sub-themes included patients’ views towards certain forms of patient input (e.g., comfort level, feasibility, alignment with perceptions of facilitators, and barriers to access to therapies) and their place within existing activities, such as clinical trial design or the development of natural history registries. The results of the qualitative analysis were used to create a version of the matrix that not only contained priorities of participants in the last two workshops, but also reflected the views of participants in the first two workshops. In addition, they were used to assess the level of potential impact of each opportunity/activity on a specific decision uncertainty as either direct or indirect. For example, participation in clinical trials provides information that can directly address uncertainties in clinical benefit. However, it may only indirectly address uncertainties around adoption/diffusion, since clinical trials are often restricted to specific patients, who may not reflect the patient population within a certain jurisdiction. Feedback on this matrix was sought through a focus group of patients and families invited to participate in a national summit on access to orphan and ultra-orphan drugs. Their comments were incorporated into a final matrix of patient priorities for involvement.

Development of a Policy Framework for Involving Patients in Reducing Decision Uncertainties Around Orphan and Ultra-Orphan Drugs

Using the Kingdon Multiple Streams Model as the theoretical foundation and the elements of a matrix, a policy framework for patient input was developed [7]. This is the underlying basis for the ‘multiple streams’ model of policy making first put forth by John Kingdon in 1995 [8]. This model suggests that in order for a policy to be developed and accepted, there must be a convergence of three ‘streams’. These are the ‘problem stream’ (which asks the question, “is the current condition considered a problem?” and, therefore, consists of issues that individuals feel need to be addressed); the ‘policy stream’ (which asks the question, “are there policy alternatives that could be implemented?” and, therefore, consists of ideas and potential solutions that have yet to gain acceptance by policy communities); and the ‘politics stream’ (which asks the question, “are policy-makers willing and able to make a policy change?” and, therefore, consists of acceptability by policy communities, campaigns by advocacy groups and potential legislative considerations). When these three streams converge at a point in time, a ‘policy window’ could open and allow for a policy solution to a problem to be accepted and implemented.

When applied to rare diseases, the problem stream comprises the different types of decision uncertainties. The policy stream represents options for reducing these uncertainties through the engagement of patients at various stages of the technology life cycle. Finally, the political stream describes policy communities who need to accept particular forms of patient involvement if they are to be implemented. The implementation of certain roles for patients along the life-cycle will only be possible when there is a convergence of the three streams.

As part of initial efforts to validate the framework, views on its structure and content were sought from Canadian regulators and payers who are part of a multidisciplinary research team funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) called ‘Promoting Rare Disease Innovations through Sustainable Mechanisms (PRISM)’. Feedback received was incorporated into a revised version of the framework.

The project was approved by the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics Board.

Results

Preferences of the Canadian Rare Disease Patient Communities Around Opportunities Identified

In addition to the final matrix of patient-prioritized activities described below, the following seven main themes were identified through the qualitative analyses of workshop transcripts (Table 1). Each theme is supported by illustrative quotations from workshop participants.

Table 1.

Themes and sub-themes related to patient input identified through patient workshops

| Patient registries |

| Providing data |

|

Providing information on disease and its impact on patients and families through natural history registries Reporting on outcomes when receiving treatment Participating in ongoing monitoring and data collection from the moment regulatory approval is obtained Providing ‘subjective’ data, such as patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient satisfaction |

| Reimbursement process |

| Providing information on the patient experience |

|

Presenting individual cases, as well as data that is difficult to quantify, through testimonials and presentation to decision makers Participate in the decision-making process Providing input in the creation of decision parameters Funding studies on cost of not funding a drug Participating on decision-making panels, providing input and clarifying the input from patient submissions Accepting when evidence of efficacy is insufficient Right to appeal Presenting individual case when a negative funding decision has been made Adding to submissions where information provided by the manufacturer was insufficient |

| Value definition |

|

Defining value Defining the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures Designing endpoints Providing input in the creation of endpoints that are relevant, meaningful, and functional |

| Clinical trials |

|

Designing trials Setting clinically meaningful endpoints Setting patient inclusion/exclusion criteria for trial participation Providing data Participating in clinical trials |

| Benefit–harm assessment |

|

Input into benefit–harm trade-off acceptability decisions Providing information on tolerance Making final benefit–harm trade-off decision |

| Early studies and drug discovery |

|

Input into research decisions Guiding decisions regarding which rare diseases to focus on in research |

| Managed access |

|

Providing information on the patient experience Providing input into the design of a structured approach to collecting information on patient experiences Patient registries Participating in registries as part of data collection for managed access plans Stopping criteria Deciding on stopping criteria with input from a specialist with relevant expertise |

Patient Registries

Patient registries were raised on numerous occasions as being an important tool to monitor rare diseases and their treatments.

“But imagine if there was an international registry that harmonized parameters. You could probably drive the p values down and maybe get some HTA that works.”

It was felt that registries would be an efficient way of getting large enough numbers of patients so as to be able to do meaningful statistics, the lack of which is often an obstacle to getting an orphan drug funded.

Reimbursement Process

Another theme that emerged in the discussions was the reimbursement process. In Canada, coverage for orphan and ultra-orphan drugs is viewed by patients and families as one of the main issues affecting the rare disease community.

“One of the difficulties, and this comes back to my own experience, I was denied and I asked if I could address the committee and the committee of course said no because they don’t want to see me. They would much rather just see the paper work because if they actually saw me, I might be convincing and they would hate to run against their own initial assessment. And I think patients have certain rights in this regard and that is that we should be able to address.”

Other common complaints from the patients included a lack of an individual patient’s voice during reimbursement review meetings, the absence of a truly fair appeal process and opacity in the decision parameters that seem to be used by committees.

Value Definition

The value definition, which relates to factors considered when assessing the impact of a therapy on patients, families, and the broader community/society, emerged as an important theme.

“I think you still need the patient… I think the patient is critical, and the caregiver, to put a framing around what that means to them versus just the hard core data.”

As experts in their own disease, patients and families felt that they were best able to judge improvements in or worsening health. They expressed concern that the choice of outcome measures in trials often reflects what is easy to measure, rather than what is of value to patients and families. As a result, the trials fail to capture the true value of a therapy.

Clinical Trials

A prominent theme throughout the four workshops comprised the design and conduct of clinical trials.

“Because we’re talking about all the problems that happen after clinical trials are designed by people who know the science and the industry, but don’t know the disease and that’s the problem. We’re dealing with the problems because we’re not included before the trial begins.”

Patients and families were frustrated over the lack of opportunities for patient input into the design of trials, given that they are increasingly being asked to help identify potential patients or participate in the trials themselves. They felt that those involved in the design and conduct of trials need to recognise the importance of involving patients in protocol development to not only ensure that trials incorporate meaningful endpoints, but also optimize trial participation.

Benefit–Harm Assessment

The fifth theme centred on assessment of benefits and harms.

“What makes more sense than asking the person who’s going to bear the risk to help with the risk–benefit trade-off?”

Patients and families felt that throughout the technology lifecycle, decisions around what constitutes acceptable harm in order to achieve a certain magnitude of benefit are often made with little input from them. They felt that the existing paternalistic approach needs to be replaced with one that recognizes patients and families as empowered equal partners in such decisions.

Early Studies and Drug Discovery (R&D)

For many patients and families living with rare diseases, there are no treatments beyond supportive care. Therefore, the need for research that could lead to the development of new therapies was a dominant theme shared by all four workshops. Given that resources available for research are limited, patients and families felt that they should have a role in setting research funding priorities to ensure that decisions reflect a comprehensive understanding of the potential implications of different proposals.

“…well, a lot of foundations that I work with, so they don’t fund basic research they only fund tools to advance drugs.”

Managed Access

The final theme related to managed access as a decision option for payers. Briefly, managed access comprises a conditional funding option, which makes therapies available to eligible patients on the basis of an agreement. The terms of the agreement may include collection of certain types of data or specific clinical or financial outcomes that must be achieved in order to receive continued funding.

“Could there be a time, like let’s say this is a new drug, there’s not enough information, could there be in the framework that why not do a study those who want to try the new drug? Not everyone wants to try a new drug. Everybody’s just assuming that everybody wants this. Some want it, some stay on the other. Do a comparative study and then decide.”

Two other themes were noted: ‘public and patient awareness’, and ‘patient experts’. Neither was included in the list of themes, since workshop participants placed them outside the technology lifecycle–decision uncertainty matrix. It was clear that more awareness of rare diseases and their implications is needed across patient communities and the general public. While it may be possible that increased awareness could impact decision uncertainties, its role in reducing a particular uncertainty at a particular step of the life cycle was not clear to participants. With respect to ‘patient experts’, participants felt that it was important they be recognized as experts in their disease by other stakeholder communities.

The final matrix of patient-identified priorities for their involvement is presented in Table 2. The organization of the elements in each cell uses the themes presented in Table 1. Patient registries were identified by the patients as a necessary way in which they could contribute to the reduction of all four existing uncertainties throughout the life cycle. They also felt strongly that the value of a drug should be defined by patients, and that this would likely reduce the uncertainties at the clinical trials step, the regulatory approval step, the post-marketing step, and the reimbursement decision-making step. They also felt that they ought to be able to provide their views on benefit–harm trade-offs, and to establish tolerance levels for a specific drug. Finally, they felt that there should be means of providing new orphan drugs under ‘managed access’ programs; that is, by providing data during the period when the drug is made available to them, and agreeing on stopping criteria (when the patient will stop the drug) with input from a relevant specialist physician.

Table 2.

Patient priorities for input mapped onto the decision uncertainty matrix

| Step in technology lifecycle | Type of uncertainty | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical benefit | Value for money | Affordability | Adoption/diffusion | |

| Pre-clinical phase |

Patient registries Providing data Develop or initiate registries [C (indirect); D (direct)] Provide information on the disease and its impact on patients and families through natural history registries [C (indirect); D (direct)] |

|||

|

Value definition Designing endpoints Provide input in the creation of endpoints that are relevant, meaningful, and functional [C (direct); D (direct)] |

||||

|

Early studies and drug discovery Input into research decisions Guide decisions regarding research priorities [C (indirect); D (indirect)] |

||||

| Clinical trials |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (indirect); C (indirect); D (direct); E (indirect); F (indirect)] B (indirect)? Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (indirect); B (direct); E (direct)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient satisfaction [A (indirect); B (direct); E (direct); F (indirect)] |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (indirect); E (indirect); F (indirect); G (indirect); J (direct)] Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); G (indirect); J (direct)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); F (indirect); G (indirect); J (direct)] |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (indirect); J (direct)] Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (indirect); J (direct)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (indirect); J (direct)] |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (indirect); J (direct)] Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (indirect); L (indirect); M (indirect); N (direct)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (indirect); L (indirect); M (indirect); N (direct)] |

|

Value definition Defining value Define the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures [C (direct); E (indirect); F (direct)] Designing endpoints Provide input in the creation of endpoints that are relevant, meaningful, and functional [C (indirect); E (indirect); F (direct)] |

Value definition Defining value Define the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures [G (indirect)] Designing endpoints Provide input in the creation of endpoints that are relevant, meaningful and functional [C (indirect); G (indirect)] |

Value definition Defining value Define the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures [J (indirect)] |

Value definition Defining value Define the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures [L (indirect); M (direct); N (indirect)] Designing endpoints Provide input in the creation of endpoints that are relevant, meaningful and functional [C (indirect); L (indirect); M (direct); N (indirect)] |

|

|

Clinical trials Designing trials Set clinically meaningful endpoints [B (direct); C (direct); D (indirect); E (direct); F (direct)] Set patient inclusion/exclusion criteria for trial participation [A (direct); B (direct); C (direct); E (direct)] Providing data Participate in clinical trials [A (direct); B (direct); C (direct); E (direct)] |

Clinical trials Designing trials Set clinically meaningful endpoints [B (direct); C (direct); D (indirect); E (direct); F (direct)] Set patient inclusion/exclusion criteria for trial participation [A (direct); B (direct); C (direct); E (direct)] Providing data Participate in clinical trials [A (direct); B (direct); C (direct); E (direct)] |

|||

| Regulatory approval |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (indirect); B (indirect); C (indirect); D (direct); E (indirect); F (indirect)] Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (indirect); B (direct); E (direct)] Participate in ongoing monitoring and data collection [A (indirect); B (direct); E (direct)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (indirect); B (direct); E (direct); F (indirect)] |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (indirect); E (indirect); G (indirect); J (direct)] Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (indirect); B (direct); E (direct); G (indirect); J (direct)] Participate in ongoing monitoring and data collection [A (indirect); B (direct); E (direct); G (indirect); J (direct)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (indirect); B (direct); E (direct); F (indirect) G (indirect); J (direct)] |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (indirect); J (direct)] Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (indirect); J (direct] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (indirect); J (direct)] |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (indirect); J (direct)] Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (indirect); L (indirect); M (indirect); N (direct)] Participate in ongoing monitoring and data collection [A (indirect); L (indirect); M (indirect); N (direct)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (indirect); L (indirect); M (indirect); N (direct)] |

|

Value definition Defining value Define the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures [C (direct); E (indirect); F (direct) |

Value definition Defining value Define the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures [G (indirect)] |

Value definition Defining value Define the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures [J (indirect)] |

Value definition Defining value Define the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures [L (indirect); M (indirect); N (indirect)] |

|

|

Benefit–harm assessment Input into benefit–harm trade-off acceptability decisions Provide information on tolerance [A (indirect); B (direct); C (indirect); E (direct); F (indirect)] Make final benefit–harm trade-off decision [F (direct)] |

Benefit–harm assessment Input into benefit–harm trade-off acceptability decisions Provide information on tolerance [A (indirect); B (direct); C (indirect); E (direct); F (indirect)] Make final benefit–harm trade-off decision [F (direct)] |

Benefit–harm assessment Input into benefit–harm trade-off acceptability decisions Provide information on tolerance [A (indirect); B (indirect); J (indirect); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] Make final benefit–harm trade-off decision [F (direct); L (direct)] |

||

| Post-marketing/real world studies |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (direct), C (indirect); D (direct); E (indirect); F (indirect)] Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct)] Participate in ongoing monitoring and data collection [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); F (indirect)] |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (indirect); E (indirect); G (indirect), J (direct)] Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); G (indirect), J (direct)] Participate in ongoing monitoring and data collection [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); G (indirect), J (direct)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); F (indirect); G (indirect), J (direct)] |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (indirect); J (direct)] Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (indirect); J (direct]; K (indirect)] Participate in ongoing monitoring and data collection [A (indirect); J (direct); K (indirect)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (indirect); J (direct); K (indirect)] |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (indirect); J (direct)] Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (indirect); L (indirect); M (indirect); N (indirect)] Participate in ongoing monitoring and data collection [A (indirect); L (indirect); M (indirect); N (indirect)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (indirect); L (indirect); M (indirect); N (indirect)] |

|

Value definition Defining value Define the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures [A (direct); C (direct); E (indirect); F (direct)] Designing endpoints Provide input in the creation of endpoints that are relevant, meaningful and functional [A (direct); C (indirect); E (indirect); F (direct)] |

Value definition Defining value Define the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures [G (indirect)] Designing endpoints Provide input in the creation of endpoints that are relevant, meaningful and functional [C (indirect); G (indirect)] |

Value definition Defining value Define the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures [J (indirect)] |

Value definition Defining value Define the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures [L (indirect); M (indirect); N (indirect)] Designing endpoints Provide input in the creation of endpoints that are relevant, meaningful and functional [A (direct); C (indirect); L (indirect); M (direct); N (indirect)] |

|

|

Benefit–harm assessment Input into benefit–harm trade-off acceptability decisions Provide information on tolerance [A (direct); B (direct); C (indirect); E (direct); F (indirect)] |

Benefit–harm assessment Input into benefit–harm trade-off acceptability decisions Provide information on tolerance [A (indirect); B (direct); C (indirect); E (direct); F (indirect)] Make final benefit–harm trade-off decision [F (direct)] |

Benefit–harm assessment Input into benefit–harm trade-off acceptability decisions Provide information on tolerance [F (direct); L (direct); K (indirect)] |

Benefit–harm assessment Input into benefit–harm trade-off acceptability decisions Provide information on tolerance [A (direct); B (indirect); J (indirect); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] |

|

| Reimbursement decision-making |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (direct), C (indirect); D (direct); E (indirect); F (indirect)] Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct)] Participate in ongoing monitoring and data collection [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); F (indirect)] |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (direct); E (direct); G (indirect), J (direct)] Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); G (indirect), J (direct)] Participate in ongoing monitoring and data collection [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); G (indirect), J (direct)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); F (indirect); G (indirect), J (direct)] |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (indirect); J (direct)] Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (indirect); J (direct]; K (indirect)] Participate in ongoing monitoring and data collection [A (indirect); J (direct); K (indirect)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (indirect); J (direct); K (indirect)] |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (indirect); J (direct)] Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (indirect); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] Participate in ongoing monitoring and data collection [A (indirect); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (indirect); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] |

|

Value definition Defining value Define the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures [A (direct); C (direct); E (indirect); F (direct)] |

Value definition Defining value Define the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures [G (indirect)] |

Value definition Defining value Define the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures [J (indirect)] |

Value definition Defining value Define the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures [L (indirect); M (indirect); N (indirect)] |

|

|

Benefit–harm assessment Input into benefit–harm trade-off acceptability decisions Provide information on tolerance [A (direct); B (direct); C (indirect); E (direct); F (indirect)] Make final benefit–harm trade-off decision [F (direct)] |

Benefit–harm assessment Input into benefit–harm trade-off acceptability decisions Provide information on tolerance [A (indirect); B (direct); C (indirect); E (direct); F (indirect)] Make final benefit–harm trade-off decision [F (direct)] |

Benefit–harm assessment Input into benefit–harm trade-off acceptability decisions Provide information on tolerance [F (direct); L (direct); K (indirect)] |

Benefit–harm assessment Input into benefit–harm trade-off acceptability decisions Provide information on tolerance [A (indirect); B (indirect); J (indirect); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] Make final benefit–harm trade-off decision [F (direct); L (direct)] |

|

|

Reimbursement process Provide information on the patient experience Present individual cases, as well as data that is difficult to quantify, through testimonials and presentation to decision makers [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct)] Participate in the decision-making process Provide input in the creation of decision parameters [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct)] Participate on decision-making panels, providing input and clarifying the input from patient submissions [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct)] Accept when evidence of efficacy is insufficient [F (indirect)] Right to appeal Present individual case when a negative funding decision has been made [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct)] Add to submissions where information provided by the manufacturer was insufficient [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct)] |

Reimbursement process Provide information on the patient experience Present individual cases, as well as data that is difficult to quantify, through testimonials and presentation to decision makers [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct); G (direct); M (indirect)] Participate in the decision-making process Provide input in the creation of decision parameters [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct); G (direct); H (indirect); I (indirect)] Participate on decision-making panels, providing input and clarifying the input from patient submissions[A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct); G (direct); H (indirect); I (indirect)] Accept when evidence of efficacy is insufficient [F (indirect); H (indirect); I (indirect)] Right to appeal Present individual case when a negative funding decision has been made[A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct); G (direct)] Add to submissions where information provided by the manufacturer was insufficient [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct); G (direct)] |

Reimbursement process Provide information on the patient experience Present individual cases, as well as data that is difficult to quantify, through testimonials and presentation to decision makers [G (direct); H (indirect); J (direct); K (direct)] Participate in the decision-making process Provide input in the creation of decision parameters [G (direct); H (indirect); J (direct); K (direct); M (direct); N (direct); O (direct)] Participate on decision-making panels, providing input and clarifying the input from patient submissions [G (direct); H (indirect); J (direct); K (direct); M (direct); N (direct); O (indirect)] Accept when evidence of efficacy is insufficient [G (direct); H (indirect); J (direct); K (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] |

Reimbursement process Provide information on the patient experience Present individual cases, as well as data that is difficult to quantify, through testimonials and presentation to decision makers [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); F (direct); G (direct); H (indirect); J (direct); K (direct); L (direct); M (indirect); N (direct); O (direct)] Participate in the decision-making process Provide input in the creation of decision parameters [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); F (direct); G (direct); H (indirect); J (direct); K (direct); L (direct); M (indirect); N (direct); O (direct)] Participate on decision-making panels, providing input and clarifying the input from patient submissions [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); F (direct); G (direct); H (indirect); J (direct); K (direct); L (direct); M (indirect); N (direct); O (direct)] Accept when evidence of efficacy is insufficient [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); F (direct); G (direct); H (indirect); J (direct); K (direct); L (direct); M (indirect); N (direct); O (direct)] Right to appeal Present individual case when a negative funding decision has been made [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); F (direct); G (direct); L (indirect); M (direct); N (direct)] Add to submissions where information provided by the manufacturer was insufficient [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); F (direct); G (direct); L (indirect); M (direct); N (direct)] |

|

|

Managed access Providing information on the patient experience Providing input into the design of a structured approach to collecting information on patient experiences [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] Patient registries Participate in registries as part of data collection for managed access plans (MAPs) [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct); J (direct)] Stopping criteria Decide on stopping criteria with input from a specialist with relevant expertise [A (indirect); B (indirect); E (indirect); F (indirect); K (indirect); M (direct); N (direct)] |

Managed access Providing information on the patient experience Providing input into the design of a structured approach to collecting information on patient experiences [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct); G (direct); K (indirect); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] Patient registries Participate in registries as part of data collection for MAPs [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct); G (direct); H (indirect); J (direct); K (indirect)] Stopping criteria Decide on stopping criteria with input from a specialist with relevant expertise [A (indirect); B (indirect); E (indirect); F (indirect); G (direct); H (indirect); K (indirect); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] |

Managed access Providing information on the patient experience Providing input into the design of a structured approach to collecting information on patient experiences [A (indirect); B (indirect); E (indirect), F (indirect); K (direct); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] Patient registries Participate in registries as part of data collection for MAPs [A (indirect); B (indirect); E (indirect), F (indirect); H (indirect); J (direct); K (direct); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] Stopping criteria Decide on stopping criteria with input from a specialist with relevant expertise [A (indirect); B (indirect); E (indirect); F (indirect); H (indirect); K (indirect); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] |

Managed access Providing information on the patient experience Providing input into the design of a structured approach to collecting information on patient experiences [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct); G (direct); K (indirect); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] Patient registries Participate in registries as part of data collection for managed access plans (MAPs) [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct); G (direct); H (indirect) K (indirect); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] Stopping criteria Decide on stopping criteria with input from a specialist with relevant expertise [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct); G (direct); H (indirect) K (indirect); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] |

|

| Introduced as insured service/ use in routine clinical practice |

Patient registries Providing data Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); G (direct); L (indirect); M (indirect); N (indirect)] Participate in ongoing monitoring and data collection [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); G (direct); L (indirect); M (indirect); N (indirect)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); F (indirect); G (direct); L (indirect); M (indirect); N (indirect)] |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (direct); E (direct); G (indirect), J (direct)] Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); G (indirect), J (direct)] Participate in ongoing monitoring and data collection [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); G (indirect), J (direct)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); F (indirect); G (indirect), J (direct)] |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (indirect); J (direct)] Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (indirect); J (direct]; K (direct)] Participate in ongoing monitoring and data collection [A (indirect); J (direct); K (direct)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (indirect); J (direct); K (direct)] |

Patient registries Providing data Provide information through natural history registries [A (indirect); J (direct)] Report on outcomes when receiving treatment [A (indirect); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] Participate in ongoing monitoring and data collection [A (indirect); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] Provide ‘subjective’ data, such as PROs and patient satisfaction [A (indirect); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] |

|

Value definition Defining value Define the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures [J (direct)] |

Value definition Defining value Define the meaningfulness of clinical outcome measures [J (indirect)] |

|||

|

Managed access Providing information on the patient experience Providing input into the design of a structured approach to collecting information on patient experiences [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct); G (direct); J (direct); K (indirect); M (direct); N (direct)] Patient registries Participate in registries as part of data collection for managed access plans (MAPs) [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct); G (direct); J (direct); K (indirect); M (direct); N (direct)] Stopping criteria Decide on stopping criteria with input from a specialist with relevant expertise [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct); G (direct); J (direct); K (indirect); M (direct); N (direct)] |

Managed access Providing information on the patient experience Providing input into the design of a structured approach to collecting information on patient experiences [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct); G (direct); K (indirect); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] Patient registries Participate in registries as part of data collection for MAPs [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct), F (direct); G (direct); H (indirect); J (direct); K (indirect)] Stopping criteria Decide on stopping criteria with input from a specialist with relevant expertise [A (direct); B (direct); E (direct); F (direct); G (direct); H (indirect); K (indirect); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] |

Managed access Providing information on the patient experience Providing input into the design of a structured approach to collecting information on patient experiences [A (indirect); B (indirect); E (indirect), F (indirect);G (direct); K (direct); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] Patient registries Participate in registries as part of data collection for MAPs [A (indirect); B (indirect); E (indirect), F (indirect); G (direct); H (indirect); J (direct); K (direct); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] Stopping criteria Decide on stopping criteria with input from a specialist with relevant expertise [A (indirect); B (indirect); E (indirect); F (indirect); G (direct); H (indirect); K (indirect); L (direct); M (direct); N (direct)] |

||

Policy Framework for Involving Patients in Reducing Decision Uncertainties Around Orphan and Ultra-Orphan Drugs

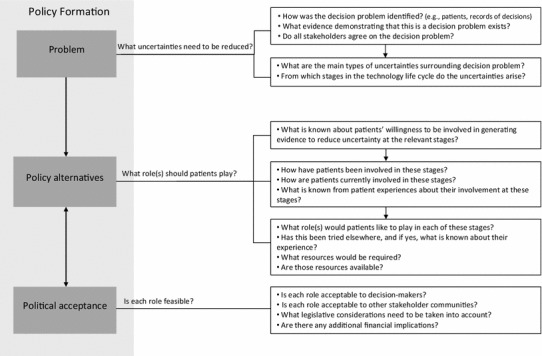

A framework for determining when and how to involve patients in generating information to reduce uncertainties in decision making on orphan and ultra-orphan drugs using Kingdon’s multiple streams model is presented in Fig. 1. It begins with recognition of a decision problem (‘problem stream’) by one stakeholder group. Evidence confirming the problem is then gathered and presented to all stakeholder groups. Once consensus on the problem is achieved, the underlying uncertainty (e.g., clinical benefit, value for money, etc.) and the stages in the lifecycle from which it arises are identified. Subsequently, policy alternatives are considered (‘policy stream’). These refer to role(s) for patients in reducing the uncertainties that they deem acceptable. Using the matrix presented in Table 2, an initial list of potential roles corresponding to the relevant type(s) of uncertainty and stage(s) in the lifecycle is first generated. For each role, a series of questions intended to provide insights into its acceptability by patients are then asked. These questions relate to patients’ willingness to be involved in this way, their previous experiences in similar roles, and the availability of any required resources. Based upon patients’ responses to the questions, a short list of ‘acceptable’ roles is created. Once patient consensus around the list is obtained, it moves onto the final phase, political acceptance (political stream’). During this phase, decision makers, along with other stakeholder communities, assess the acceptability of each role on the short list from their perspective. Legislative considerations and financial implications are also taken into account during deliberations in order to arrive at acceptable and feasible roles for patients.

Fig. 1.

Proposed policy framework for patient input into reducing decision uncertainties

Discussion

The workshops reiterated the fact that rare disease patients in Canada are more than willing to engage in various activities throughout the life cycle of an orphan or ultra-orphan drug. They actively identified potential opportunities whereby they could contribute information on any stage of the life cycle that might help reduce uncertainties that physicians and regulatory and reimbursement decision makers are often challenged by. The most pressing concern, in their view, was uncertainty in the knowledge on the clinical benefit of a treatment for a rare disease. This uncertainty which arises often from small-scale clinical trials, often ties the hands of regulators and payers. However, the patients and caregivers at the workshops offered a number of suggestions as to how they could help reduce this particular uncertainty. One direct way to achieve this is by increasing participation in clinical trials, which patients proposed they do. One other suggestion was that patients have an active early role in specifying the relevant outcome measures for clinical trials.

As far as the uncertainty in value for money was concerned, the patients felt that their contributions would be limited to reducing the uncertainty in clinical benefit, which is most often the ‘value’ component of value for money. By and large, patients felt that they had little control over the ‘money’ component, and so did not think they could have any influence on it.

The patients also felt that they could play a role in reducing the uncertainty in the affordability of a treatment. They proposed doing this by continuing to provide clinical data during the reimbursement stage. One way of doing this would be with managed access schemes, in which there is continuous monitoring of individual patients which could reduce the inappropriate use of a treatment which proves ineffective for some patients.

What has been referred to as ‘opportunities’ for patients and patient organizations are really the contents of the policy stream within a multiple streams model of policy making. Whether any of these potential solutions to reduce uncertainty actually gets accepted by policy makers depends on the politics stream and the problem stream, whose contents are the uncertainties. All of this will be highly context-dependent. In some jurisdictions, rare-disease patient engagement of the types described here are much more advanced than in some other jurisdictions. This is due at least in part to the fact that policy windows have opened from time to time, and policy makers have listened to the stakeholders and found the political environment to be receptive to changes.

In Canada, research of the type reported in this (and the earlier [3]) paper has, in recent years, shown that the problem stream (uncertainties about rare disease and its management) and the policy stream, at least from the patients’ perspective (activities that they are willing to participate in) have been clearly elucidated. At the same time, there is heightened awareness by Canadian governments and society more generally, about the challenges of managing rare diseases. The federal government is currently developing an orphan drug regulatory framework and the provincial and territorial governments have established a working group to develop a pan-Canadian approach to funding orphan and ultra-orphan drugs. From the perspective of the Kingdon model of policy development, it would appear that there will be opportunities for policy windows to open, and new policies regarding orphan and ultra-orphan drugs implemented.

Conclusions

While the importance of patient input into policy decisions has become widely recognized, the objective of that input is not always clear. In this paper, we defined the roles of patients as key producers of evidence and, in turn, knowledge needed to reduce different types of decision uncertainties that arise during the life cycles of orphan and ultra-orphan drugs. These uncertainties, some of which stem from the often limited understanding of the natural history and epidemiology of most rare diseases, and some from the treatments themselves, are considerable.

Where traditional forms of evidence and expertise are lacking, patients, as experts in their disease and its individual and social impact, may play critical roles. We proposed a framework that aims to enhance the effectiveness of patient involvement by connecting roles to explicit decision needs and assessing their acceptability and feasibility from the perspectives of multiple stakeholders.

Acknowledgments

The work reported in this paper was made possible by an Emerging Team Grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research on “Developing Effective Policies for Managing Technologies for Rare Diseases”.

Author contributions

T Stafinski made substantial contribution to the conception and planning of the work that led to this manuscript, to the analysis and interpretation of the data, to drafting, critical revision and final approval of the manuscript.

D. Menon made substantial contribution to the conception and planning of the work that led to this manuscript, to the interpretation of the data, to critical revision and final approval of the manuscript, and is the overall guarantor of the work.

A. Dunn made substantial contribution to the conception and planning of the work that led to this manuscript, to the analysis and interpretation of the data, to drafting, critical revision and final approval of the manuscript.

D. Wong-Rieger made substantial contribution to the conception and planning of the work that led to this manuscript, to the analysis and interpretation of the data, and to final approval of the manuscript.

None of the authors has any financial or non-financial conflicts of interest to declare.

Appendix 1: Questions related to each type of uncertainty

Clinical benefit

Are the benefits observed in the trial generalizable to the patient population within the relevant jurisdiction?

Does the level of health gain observed vary across patient subtypes?

Which outcomes should be measured?

What is the natural progression of the disease?

What is known about the effect of the drug compared to that of current best practice?

What is the meaningfulness to patients of the health gain attributable to the drug?

Value for money

-

(g)

What are the broader implications associated with the drug, beyond clinical benefit?

-

(h)

What opportunity costs are associated with funding the drug?

-

(i)

What is known about society’s willingness to pay for the expected gain?

Affordability

-

(j)

How many patients are expected to benefit from the drug?

-

(k)

What is the expected cost per patient per year?

Adoption/diffusion

-

(l)

How will access to the drug be managed?

-

(m)

Who has the expertise to decide on starting and stopping criteria?

-

(n)

Are mechanisms compelling patients and physicians to ensure appropriate use required?

-

(o)

Are there other drugs in the pipeline that may affect utilization of this drug in the near future?

References

- 1.RARE facts and statistics. Aliso Viejo (CA): The Global Genes Project; 2012. https://globalgenes.org/rarefacts/. Accessed 31 May 2014.

- 2.Fronstin P. Findings from the 2013 EBRI/Greenwald & Associates Consumer Engagement in Health Care Survey. EBRI Issue Brief. 2013;393:4–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menon D, Stafinski T, Dunn A, Short H. Involving patients in reducing decision uncertainties around orphan and ultra-orphan drugs: a rare opportunity?. Patient. 2015 (submitted for publication). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Short H, Stafinski T, Menon D. A national approach to reimbursement decision-making on drugs for rare diseases in Canada? Insights from across the ponds. Healthcare Policy 2015 (submitted for publication). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Analyzing qualitative data. New York (NY): Routledge; 1994. Accessed.

- 6.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess RG, editors. Analyzing qualitative data. New York (NY): Routledge; 1994. pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zakariadis N. The multiple streams framework, structures, limitations. In: Sabatier P, editor. Theories of the policy process. Boulder: Westview Press; 2007. pp. 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kingdon JW. Agendas, alternatives and public policies. 2nd ed. New York: Harper Collins; 1995. Accessed.