Abstract

The most frequently cited policy solution for improving access to hospice care for patients and families is to expand hospice eligibility criteria under the Medicare Hospice Benefit. However, the substantial implications of such a policy change have not been fully articulated or evaluated. This paper seeks to identify and describe the implications of expanding Medicare Hospice Benefit eligibility on the nature of hospice care, the cost of hospice care to the Medicare program, and the very structure of hospice and palliative care delivery in the United States. The growth in hospice has been dramatic and the central issue facing policymakers and the hospice industry is defining the appropriate target population for hospice care. As policymakers and the hospice industry discuss the future of hospice and potential changes to the Medicare Hospice Benefit, it is critical to clearly delineate the options—and the implications and challenges of each option—for improving access to hospice care for patients and families.

INTRODUCTION

As the Medicare Hospice Benefit (MHB) marks its twenty-fifth anniversary, there is much to celebrate in terms of the growth in the number of hospice agencies and patient and family beneficiaries of hospice care, the increase in diversity of patient diagnoses being served by hospice, and recent indications of increasing lengths of stay with hospice.1 However, there remains substantial concern regarding access to high-quality end-of-life care, including hospice. Many patients and families continue to experience unmet pain and symptom management, overall dissatisfaction with care, inappropriate prolongation of the dying process, lack of control, and death in a hospital rather than at home.

Currently, only approximately one-third of Medicare beneficiaries enroll with hospice prior to death.1 Many in the field of palliative care view the structure of the MHB as a major barrier to the use of hospice2–5 and an increasing number of experts recommend expanding MHB eligibility criteria to improve access to hospice care. However, there has been no comprehensive discussion of the implications of expanding MHB eligibility on the nature of hospice care, the cost and comprehensiveness of the benefit, and, more generally, on the structure of the growing palliative care industry. The purpose of this paper is to delineate the implications of expanding MHB eligibility and thus to promote a more informed debate regarding improving access to high-quality care in the end of life.

THE ORIGINS OF HOSPICE

Hospice care in the United States began in the 1970s as a social movement that focused on providing a higher quality death than that typically experienced in the hospital setting, where dying patients often suffered from significant pain and discomfort, did not receive the emotional and spiritual support necessary to cope with their death, and faced uncertainty as to whether the life-prolonging medical interventions that they were subjected to were consistent with their goals of care at the end of life.6 Hospice was originally provided by “charitable”6 and “charismatic”7 leaders working individually or through nonprofit community-based agencies, caring for patients in their own homes and relying on charitable donations as the sole revenue source. Despite growing support in the early 1970s for the general principles embraced by hospice, the concept (comfort rather than curative care), setting (home rather than hospital care), and focus (patient and family rather than patient) of hospice care were still considered experimental in nature.

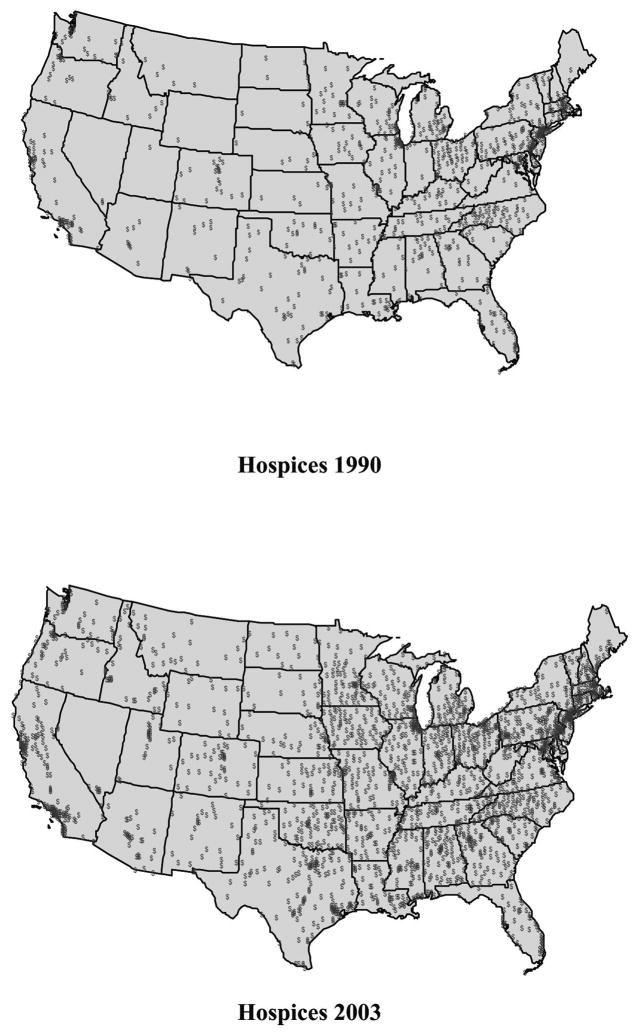

The passing of the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act (TEFRA) in 1982 marked a critical turning point for the hospice movement. The TEFRA authorized Medicare to reimburse for hospice services and thus hospice became publicly funded under the MHB. The number of Medicare-certified hospices began to increase from 45 in 1983 to 814 in 1989. With a 20% increase in reimbursement rates in 1989,8 there was even further growth in the number of hospice agencies. More than 2000 new Medicare certified hospice agencies emerged during the 1990s throughout the country (Fig. 1),9 including for-profit hospice agencies, which increased from only 5% of all hospices in 199010,11 to 46% of agencies by 2006.1 During this time, Medicare spending for hospice under the Medicare Hospice Benefit increased from $445 million (in 1991) to $6.6 billion (in 2006)12 and the number of Medicare beneficiaries using hospice increased more than sixfold.

FIG. 1.

The number of hospice agencies in the United States: 1990 and 2003. Source: Medicare Provider of Service files.

POLICY ISSUE: IMPROVING ACCESS TO HOSPICE CARE

Despite growth in the number of hospice agencies and beneficiaries of hospice, the MHB remains one of Medicare’s smallest programs and is used by only one-third of Medicare beneficiaries prior to death.1 The extent to which this percentage reflects underuse of hospice is unknown as it likely reflects a combination of barriers to hospice care and patient preferences to not receive hospice care prior to death. Potential barriers to hospice care include lack of knowledge regarding hospice care, lack of hospice availability, and ineligibility for hospice care under the MHB.

Some studies13–16 suggest that patient and family lack of knowledge regarding hospice services is a barrier to receipt and timeliness of hospice care and may contribute to physicians not referring patients to hospice until late in the course of the patient’s disease. Recent studies17,18 indicate that lack of hospice availability may also be a barrier to hospice use. Significant geographic variation in use of hospice has been reported19,20 with rural areas having significantly lower hospice availability 21 and use22,23 compared to urban areas.

Studies have also evaluated how the MHB eligibility criteria pose a barrier to the use of hospice. Patients are eligible to receive hospice care under the MHB if their physician certifies that they have a life expectancy of 6 months or less if their disease follows its expected course. A number of studies suggest that prognostic difficulty in adhering to this 6-month criterion plays a substantial role in limiting use of hospice.2,5,15–17,24–31 Furthermore, MHB enrollment requires that an individual forgo Medicare reimbursement for ongoing therapy or curative medical treatment related to the terminal diagnosis. This restriction has also been suggested as a contributing factor in limiting use of hospice.2,5,16,32,33 As a result, revising MHB eligibility criteria has been at the center of ongoing policy debate regarding options for increasing access to hospice care.

POLICY CHALLENGE: WHO IS THE TARGET POPULATION FOR HOSPICE CARE?

The central issue facing policy makers and the hospice industry is defining the appropriate target population for hospice care as the industry continues to grow and evolve. Specifically, should hospice: (1) serve a defined population of patients with limited life expectancy (e.g., 6 months if the disease follows its expected course) who desire palliative and supportive services as distinct from acute and curative treatments (current eligibility under the MHB) or (2) expand to include patients with serious chronic diseases who desire palliative and supportive services in concert with life-prolonging curative medical treatments regardless of life expectancy. Current eligibility under the MHB is consistent with hospice’s origins and the goals of the hospice founders: interdisciplinary care for patients with a limited life expectancy and for whom curative treatments are no longer effective or desired. The limited life expectancy34 and waiver of Medicare reimbursement for the curative treatment of the terminal condition for which hospice care is elected35 are necessary and appropriate criteria for defining this target hospice population. The advantage of maintaining the MHB eligibility criteria is that it retains a comprehensive benefit, including interdisciplinary care provided primarily in the home, for a targeted population of patients with limited life expectancy that is consistent with the core mission of hospice’s founders. The disadvantage of retaining the current eligibility criteria is that it may be increasingly difficult for individuals with uncertain diagnoses and more complex treatment options to access hospice in a timely manner. For example, although there has been significant growth in the range of diagnoses of individuals receiving hospice care,1 prognostic difficulty (i.e., difficulty in certifying that a patient has 6 months or less to live as required by the Medicare Hospice Benefit) remains a barrier to hospice referral, 26,29–31 particularly for individuals with noncancer diagnoses. Similarly, the line between curative and palliative treatments has become increasingly less distinct as a number of curative treatments simultaneously provide symptom relief.

Alternatively, eligibility for enrollment in the Medicare Hospice Benefit could shift from a prognosis-based to a needs-based criterion with no restriction on the ability to receive reimbursement for curative treatments while receiving hospice care. That is, hospice care could be integrated earlier in the course of the treatment of individuals with serious disease and hospice services could be provided in conjunction with curative and life-prolonging treatments. The obvious advantage of this option is that with a needs-based eligibility criterion, more individuals would be covered by the Medicare Hospice Benefit, regardless of their prognosis and simultaneous receipt of curative and palliative care. Life-prolonging treatments and palliative care could be better integrated, and the shift from predominantly curative to predominantly palliative care could be more gradually managed to reflect the natural course of disease. Hospice care would no longer be focused on the care of individuals in the last phases of incurable illness but would be more broadly focused on the care of individuals with serious illnesses needing multidisciplinary services. As such, the stigma that hospice is synonymous with death might be diminished causing individuals to enroll with hospice earlier and mitigate the phenomenon of inappropriately short lengths of stay with hospice.

IMPLICATIONS OF EXPANDING MEDICARE HOSPICE BENEFIT ELIGIBILITY

Nevertheless, expanding MHB eligibility poses substantial challenges to the hospice industry. First, in terms of implementation, how would a “needs-based” criterion be defined? Would it be defined as need for a single element of hospice care such as skilled nursing care or spiritual care or caregiver support? Or would it be defined as need for the full range of interdisciplinary care? When in the course of one’s disease would “need” be assessed? Precisely defining the target population under an expanded vision of hospice care is a non-trivial, critical first step in estimating the size, cost, and practicality of this alternative. Second, expanding MHB eligibility has cost implications for the overall Medicare program. The number of individuals who would enroll in the MHB would likely substantially increase, increasing overall program costs. However, the implementation of hospital palliative care programs has demonstrated that providing palliative care to individuals earlier in the course of their disease results in cost savings due to better care coordination, clarified treatment goals, and the avoidance of expensive, nonbeneficial treatments covered by Medicare Part A.36–38 The extent to which hospice programs would achieve similar cost savings is unknown. For this reason, proposals to expand MHB eligibility may result in policies to reduce the comprehensiveness of the benefit in order to maintain “budget neutrality.” Therefore, by substantially altering the existing MHB, there is a risk of having one of the most generous benefits in the Medicare program markedly reduced in comprehensiveness of services covered. Third, hospices would face significant challenges in training personnel to care for patients earlier in the course of their disease, as such patients have different medical, nursing, social, and spiritual needs that require different expertise, skills, and scope of services. Legislative issues related to state licensure requirements, which for some states restrict the types of services that hospices may provide, would need to be adjusted. Hospice programs would need to rapidly integrate themselves into all areas of mainstream medicine to better coordinate palliative and curative care and would need to enlarge and expand their scope of services to serve a broader population of patients. This integration of hospices with traditional acute and chronic care services may be viewed negatively by some hospices in that it represents a vision of hospice that is counter to hospice’s origins as an alternative to traditional medicine.

Finally, expanding the MHB eligibility has profound implications for the evolving structure of palliative care delivery in the United States. There has been dramatic recent growth in the number of non-hospice palliative care programs, the dominant model being hospital-based palliative care programs.39 These programs primarily serve patients on an inpatient or consult basis during their stay in the hospital and focus on defining the patient’s goals of care and managing pain and symptoms. Currently, there is no Medicare reimbursement for interdisciplinary hospital-based palliative care teams (although physician and advanced practice nurses may bill for services, there is no reimbursement for the palliative care team, which includes social workers, counselors, and other professionals). Hospital-based palliative care programs have grown rapidly primarily due to the increasing number of individuals who need palliative care services but are not yet eligible (because their life expectancy is longer than 6 months) and/or willing (because they are simultaneously pursuing curative care or equate hospice care with dying) to enroll in the Medicare Hospice Benefit. In many cases, hospital-based palliative care programs and hospice programs have developed in a complementary fashion with hospital-based palliative care programs referring patients to hospice either on an inpatient basis or upon patient discharge from the hospital. Expanding MHB eligibility may serve to strengthen these partnerships between hospital-based palliative care and hospice programs as both programs may increase in size and patients could be more efficiently allocated between hospital palliative care and hospice care.

However, to the extent that the Medicare Hospice Benefit is expanded to cover patients enrolling with hospice earlier in the course of their disease, hospital-based palliative care and hospice programs may instead compete for patients leaving the future role of nonhospice palliative care programs uncertain. For example, the economic justification for hospitals to establish hospital-based palliative care programs is that by working with patients and families to assess preferences for life-sustaining treatments and by developing plans of care that facilitate timely and informed decisions, hospitals can reduce length of stay and reduce costs by eliminating unnecessary or ineffective tests and procedures.40 However, if hospice agencies begin to enroll and provide palliative care services to patients who would have otherwise been served by hospital-based palliative care programs, demand for hospital-based palliative care programs may decline as the package of palliative care services provided by a hospice would be covered by Medicare whereas the package of palliative services provided by the hospital would not be covered. Thus, the business model for hospital-based palliative care programs may be weakened. Another implication of expanding MHB eligibility criteria on the structure of the palliative care industry is whether expanding eligibility for patients would occur simultaneously with expanding the types of organizations allowed to become certified hospice providers under the benefit. Nonhospice palliative care programs, such as hospital-based palliative care programs, could potentially be allowed to become certified hospice providers and receive reimbursement under the MHB. However, the challenge would become whether or not nonhospice palliative care providers would need to adhere to the Conditions of Participation (COP)41 in the MHB. For example, hospices certified to participate in the MHB must provide 80% of their patient care days to patients in their home, as opposed to in an inpatient setting. Whether or not non-hospice palliative care providers, such as hospital-based palliative care providers, would be expected to meet this standard if they were to participate in the MHB is yet another area to be considered under an expanded vision of hospice eligibility.

In conclusion, although there is fairly universal support for improving access to hospice care, there exists considerable uncertainty regarding if and how to change the Medicare Hospice Benefit to achieve this important goal. MHB eligibility is only one of potentially many barriers to receiving timely hospice care including lack of knowledge of hospice and hospice availability. The decision to move hospice in a new direction and substantially alter eligibility for the MHB, although a popular policy solution, is a decision to restructure our entire system for palliative care delivery. The advantages and challenges of such a decision, and its effect on patients and families, must be carefully considered and compared with the consequences of retaining the existing benefit. Given the substantial variation across hospice agencies in clinical sophistication and service scope,42 demonstration projects may be required to generate relevant outcomes data to evaluate policy options. Additional research is necessary regarding the elasticity of demand for hospice services (i.e., the increase in demand for hospice services if coverage for hospice care were expanded), the potential cost savings of initiating hospice earlier in the course of disease, the structure of various models of integrated hospice and non-hospice palliative care programs, and the implications of an expanded Medicare Hospice Benefit on patient and family experiences and outcomes in the end of life.

References

- 1.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. [Last accessed February 2008];NHPCO’s Facts and Figures—November 2007 edition. 〈 www.nhpco.org/files/public/2005-facts-and-figures.pdf〉.

- 2.Jennings B, Ryndes T, D’Onofrio C, Baily MA. Access to hospice care. Expanding boundaries, overcoming barriers. Hastings Cent Rep. 2003;(Suppl):S3–7. S9–13, S5–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Institute of Medicine Report: Improving Palliative Care for Cancer. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynn J, Forlini JH. “Serious and complex illness” in quality improvement and policy reform for end-of-life care. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:315–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.90901.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Last Acts: Means to a Better End: A Report on Dying in America Today. Washington, D.C: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paradis LF, Cummings SB. The evolution of hospice in America toward organizational homogeneity. J Health Soc Behav. 1986;27:370–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.James N, Field D. The routinization of hospice: Charisma and bureaucratization. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34(12):1363–1375. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90145-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Omnibus Reconciliation Act. PL101-239, Section 6005. 1989.

- 9.General Accounting Office. Medicare: More Beneficiaries Use Hospice, but for Fewer Days of Care. 2000:HEHS-00-182. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones AL. Hospices and home health agencies: Data from the 1991 National Health Provider Inventory. Adv Data. 1994;257:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strahan GW. An overview of home health and hospice care patients: Preliminary data from the 1993 National Home and Hospice Care Survey. Adv Data. 1994;256:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gazelle G. Understanding hospice—An underutilized option for life’s final chapter. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:321–324. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhodes RL, Teno JM, Welch LC. Access to hospice for African Americans: Are they informed about the option of hospice? J Palliat Med. 2006;9:268–272. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherlin E, Fried T, Prigerson HG, Schulman-Green D, Johnson-Hurzeler R, Bradley EH. Communication between physicians and family caregivers about care at the end of life: When do discussions occur and what is said? J Palliat Med. 2005;8:1176–1185. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.General Accounting Office. Medicare Hospice Care: Modifications to Payment Methodology May Be Warranted. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman BT, Harwood MK, Shields M. Barriers and enablers to hospice referrals: An expert overview. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:73–84. doi: 10.1089/10966210252785033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fowler K, Poehling K, Billheimer D, Hamilton R, Wu H, Mulder J, Frangoul H. Hospice referral practices for children with cancer: A survey of pediatric oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1099–1104. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.6591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gozalo PL, Miller SC. Hospice enrollment and evaluation of its causal effect on hospitalization of dying nursing home patients. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:587–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00623.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wennberg JE, Fisher ES, Stukel TA, Skinner JS, Sharp SM, Bronner KK. Use of hospitals, physician visits, and hospice care during last six months of life among cohorts loyal to highly respected hospitals in the United States. BMJ. 2004;328:607. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7440.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wennberg JE, Fisher ES, Skinner JS. Geography and the debate over Medicare reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002:W96–114. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w2.96. Suppl Web Exclusives. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Virnig BA, Ma H, Hartman LK, Moscovice I, Carlin B. Access to home-based hospice care for rural populations: Identification of areas lacking service. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1292–1299. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Virnig BA, Kind S, McBean M, Fisher E. Geographic variation in hospice use prior to death. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1117–1125. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Virnig BA, Moscovice IS, Durham SB, Casey MM. Do rural elders have limited access to Medicare hospice services? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:731–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson CB, Slaninka SC. Barriers to accessing hospice services before a late terminal stage. Death Stud. 1999;23:225–238. doi: 10.1080/074811899201055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huskamp HA, Buntin MB, Wang V, Newhouse JP. Providing care at the end of life: do Medicare rules impede good care? Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:204–211. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brickner L, Scannell K, Marquet S, Ackerson L. Barriers to hospice care and referrals: Survey of physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions in a health maintenance organization. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:411–418. doi: 10.1089/1096621041349518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christakis NA. Predicting patient survival before and after hospice enrollment. Hosp J. 1998;13:71–87. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.1998.11882889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zerzan J, Stearns S, Hanson L. Access to palliative care and hospice in nursing homes. JAMA. 2000;284:2489–2494. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christakis N. Death Foretold: Prophecy and Prognosis in Medical Care. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fox E, Landrum-McNiff K, Zhong Z, Dawson NV, Wu AW, Lynn J. Evaluation of prognostic criteria for determining hospice eligibility in patients with advanced lung, heart, or liver disease. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. JAMA. 1999;282:1638–1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.17.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simpson DA. Prognostic criteria for hospice eligibility. JAMA. 2000;283:2527. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.19.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lorenz KA, Asch SM, Rosenfeld KE, Liu H, Ettner SL. Hospice admission practices: Where does hospice fit in the continuum of care? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:725–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Casarett D, Van Ness PH, O’Leary JR, Fried TR. Are patient preferences for life-sustaining treatment really a barrier to hospice enrollment for older adults with serious illness? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:472–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.U.S. Government Printing Office. Code of Federal Regulations 42CFR418.22. Certification of Terminal Illness. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 35.U.S. Government Printing Office. Code of Federal Regulations 42CFR418.24, Election of Hospice Care. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Penrod JD, Deb P, Luhrs C, Dellenbaugh C, Zhu CW, Hochman T, Maciejewski ML, Granieri E, Morrison RS. Cost and utilization outcomes of patients receiving hospital-based palliative care consultation. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:855–860. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bruera E, Neumann CM, Gagnon B, Brenneis C, Quan H, Hanson J. The impact of a regional palliative care program on the cost of palliative care delivery. J Palliat Med. 2000;3:181–186. doi: 10.1089/10966210050085241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fromme EK, Bascom PB, Smith MD, Tolle SW, Hanson L, Hickam DH, Osborne ML. Survival, mortality, and location of death for patients seen by a hospital-based palliative care team. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:903–911. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morrison RS, Maroney-Galin C, Kralovec PD, Meier DE. The growth of palliative care programs in United States hospitals. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:1127–1134. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Center to Advance Palliative Care. [Last accessed September 2006];Building a Hospital Based Palliative Care Program: Benefits to Hospitals. 〈 www.capc.org/building-a-hospital-based-palliative-care-program/case/hospitalbenefits〉.

- 41.U.S. Government Printing Office. Code of Federal Regulations 42CFR418.50–100, Conditions of Participation. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carlson MD, Morrison RS, Holford TR, Bradley EH. Hospice care: What services do patients and their families receive? Health Serv Res. 2007;42:1672–1690. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00685.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]