Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study is to assess the feasibility and acceptability of an intervention to reduce mental health problems and bolster resilience among children living in households affected by caregiver HIV in Rwanda.

Design

Pre-post design, including 6-month follow-up.

Methods

The Family Strengthening Intervention (FSI) aims to reduce mental health problems among HIV-affected children through improved child–caregiver relationships, family communication and parenting skills, HIV psychoeducation and connections to resources. Twenty families (N=39 children) with at least one HIV-positive caregiver and one child 7–17 years old were enrolled in the FSI. Children and caregivers were administered locally adapted and validated measures of child mental health problems, as well as measures of protective processes and parenting. Assessments were administered at pre and postintervention, and 6-month follow-up. Multilevel models accounting for clustering by family tested changes in outcomes of interest. Qualitative interviews were completed to understand acceptability, feasibility and satisfaction with the FSI.

Results

Families reported high satisfaction with the FSI. Caregiver-reported improvements in family connectedness, good parenting, social support and children's pro-social behaviour (P<0.05) were sustained and strengthened from postintervention to 6-month follow-up. Additional improvements in caregiver-reported child perseverance/self-esteem, depression, anxiety and irritability were seen at follow-up (P<.05). Significant decreases in child-reported harsh punishment were observed at postintervention and follow-up, and decreases in caregiver reported harsh punishment were also recorded on follow-up (P<0.05).

Conclusion

The FSI is a feasible and acceptable intervention that shows promise for improving mental health symptoms and strengthening protective factors among children and families affected by HIV in low-resource settings.

Keywords: adolescent, Africa, child, mental disorders, mental health, paediatrics, psychotherapy

Introduction

Globally, over 16 million children have lost one or both caregivers to HIVand an estimated 5 million children are living with HIV-positive caregivers, the vast majority in sub-Saharan Africa [1–3]. These children, broadly affected by HIV, are at a high risk for mental health problems and poor developmental outcomes [4–7]. Research in a number of international settings indicates that HIV-affected children (i.e. those with HIV-positive caregivers) are at risk for a range of mental health problems, including depression, anxiety and social problems due to disrupted parent–child relationships, fear and misinformation [8]. Within these households, there is also an increased risk of family conflict, stigma, economic insecurity, poor educational outcomes in children, caregiver depression and physical impairment [4,9,10]. HIV-affected families may experience dramatic shifts of responsibilities from caregivers to children, increasing pressures on children and disempowering caregivers [11,12]. Such dynamics are exacerbated in settings such as Rwanda where the dual vectors of HIV and AIDS and the legacy of the 1994 Genocide have disrupted many traditional mechanisms of child-rearing with devastating consequences for children and families [13–15]. Despite these challenges, few evidence-based programmes have been developed to promote healthy family functioning and to prevent mental health problems in HIV-affected children in sub-Saharan Africa [16,17].

Eighty-three percent of Rwanda's children are categorized as vulnerable, with one in six made vulnerable due to HIVand AIDS [18]. Although the overall HIV prevalence rate in Rwanda has been declining and is currently estimated to be 3% [19], this trend masks the high rates of HIV among adults of caregiving age (7.9% of women between 35 and 39 years of age) [20]. Nonetheless, Rwanda has made significant strides in improving health outcomes through innovative health policies and programmes [20–22]. The country's track record in HIV care in recent years is strong: 91% of eligible HIV-positive patients receive antiretroviral therapy (ART) [20], and 92% of ART patients are retained in care [22]. With increasing access to ART, HIV is becoming a chronic illness. However, the broader consequences of HIV within families remain unaddressed.

Family-based preventive interventions (FBPIs) have important public health potential for promoting family functioning and mental health in HIV-affected children, including addressing behavioural problems that increase risk of HIV infection [23–25]. As access to HIVand AIDS testing and treatment becomes increasingly available, such interventions may be integrated into routine services for HIV-affected families, especially in situations in which HIV-positive individuals have children in the household [26,27]. To address these risks in families affected by HIV, the Family Strengthening Intervention (FSI) was developed as a locally adapted, home-based intervention. The FSI aims to improve family functioning and caregiver–child relationships, connect vulnerable families to available formal and informal services, and promote emotional and behavioural health among HIV-affected children. Its flexible format and use of a family narrative also allows families to integrate past experiences of trauma and loss at their own pace along with other family issues. This study describes an open trial to assess the feasibility, acceptability and potential of the FSI for reducing mental health problems and promoting resilience in children.

Materials and methods

The family-strengthening intervention

Development and adaptation

Development of the FSI has been described in detail in prior publications [28]. The FSI was developed using a robust iterative mixed methods process that identified culturally relevant mental health problems [29] and protective processes [30] relevant to Rwandan children and families affected by HIV and AIDS. Following reviews of the literature on prevention programmes, the FBPI [31], which is strengths-based and has demonstrated efficacy across a range of low-resource and culturally diverse settings, was selected [32–37]. The FBPI was originally designed for the prevention of depression among the offspring of depressed caregivers [38,39]. It was selected for adaptation to the context of HIV in Rwanda given its focus on resilience in the face of chronic illness and improving parenting skills, communication and overall parent–child relationships [30,32,38,40]. Standardized FBPI manuals and training materials were used as the basis for the FSI and were adapted to the Rwandan context and culture via input from local clinicians, HIV-affected caregivers, children and Community Advisory Boards (CABs).

Core components of the family-strengthening intervention

The FSI is a structured intervention with four core components: building parenting skills and improving family communication (see Table 1); developing a family narrative to increase family connectedness and hope, and highlight family resilience in the face of adversity; providing psychoeducation on HIV transmission, prevention and normative responses that family members may have when learning of their own diagnosis or that of loved ones; and strengthening problem-solving skills and social support through improved navigation of nonformal and formal resources. Supplementary psychoeducation on Genocide-related trauma and attention to integration of past experiences and present resilience is also provided as relevant. The FSI delivers these core components via six main modules (see Table 2). The number of sessions required to complete these modules may vary according to a family's needs and family size (separate sessions may be held with younger and older children in small groups as needed). In initial sessions, caregivers and children meet separately with the counsellor leading up to a family meeting led by caregivers with support from counsellors. Intervention content is presented through picture books developed for the FSI, vignettes, interactive activities and Rwandan proverbs. HIV and AIDS and trauma psychoeducation content were developed with input from a CAB and also by drawing from counselling materials used by our collaborating organization, Partners In Health/Inshuti Mu Buzima (PIH/IMB) and by the Rwandan Ministry of Health (MOH).

Table 1.

Qualitatively-derived indicators of good parenting and family connectedness in Rwanda.

| Good parenting | Family connectedness |

|---|---|

| Provide trainings | Interact with/socialize with the family |

| Provide teachings | Converse with/talk to reach agreements |

| Give advice | Understand each other |

| Help with problems | Unified/united |

| Teach good discipline | Living together in peace |

| Converse with children | Being honest with each other |

| Interact with children | Not suspicious of each other/do not hide things |

| Provide resources (food, water, clean clothes and school fees) | Work together with joined hands/cooperate with each other |

| Draw close to children | Do not have conflicts with each other |

| Express love | Happy and joyful together |

| Speak with love to children | Respect each other |

| Respect children | Love each other |

| Treat all children in the family equally | Share secrets with each other |

| Being happy with children | Keep each other's secrets |

| Parent well for the country | Parents don't cheat on each other |

| Being calm with children | Do not stigmatize each other |

| Being humble with children | Comfort each other/reassure each other |

| Socialize with children |

Table 2.

Family-strengthening intervention: Rwanda modules.

| Pre-meeting – Caregivers, children and interventionist (1–1.5 h) |

| • Introduction of the intervention and main goals |

| • Identify who in the family will participate in the intervention and what the family hopes to get out of it |

| Module 1 – Caregivers and interventionist (1.5–2 h) |

| • Develop the family narrative, or family history, with a focus on family strengths and challenges |

| • Introduce strategies for positive parenting |

| Module 2 – Caregivers and interventionist (1.5–2 h) |

| • HIV/AIDS psychoeducation for caregivers |

| • Continuation of the family narrative with a focus on how illness has affected the family |

| Module 3 – Children and interventionist (1.5–2 h) |

| • Develop the family narrative from the children's perspective |

| • Children identify the strengths and challenges of the family |

| • HIV and AIDS psychoeducation for children and discussion of illness in the family |

| Module 4 – Caregivers and interventionist (1.5–2 h) |

| • Discuss with caregivers sources of resilience in the family and the children's concerns |

| • Build parenting and communication skills |

| • Prepare caregivers for the family meeting, including role plays and setting the agenda of topics |

| Module 5 – Children and interventionist (1.5–2 h) |

| • Discuss with children sources of resilience in the family |

| • Build coping and communication skills |

| • Prepare children for the family meeting with caregiver(s), utilizing new communication skills through role plays |

| Module 6 – Family meeting with caregivers, children, and interventionist (1.5–2 h) |

| • Conduct a family meeting to establish shared goals and expand the family narrative |

| • Discuss challenges and strengths of family communication |

| Family meeting review – caregivers, children, and interventionist (1.5–2 h) |

| • Review the family meeting, discuss family goals, and inquire about family functioning |

| • Review key psychoeducation on HIV/AIDS and resilience |

| • Discuss previous and new family concerns |

| Follow-up session – caregivers, children, and interventionist (1.5–2 h) |

| • Discuss family goals and progress towards achieving them |

| • Inquire about family functioning |

| • Discuss previous and new family concerns |

Counsellor selection, training and supervision

Counsellors were six (four women) Rwandan bachelor-level psychologists, fluent in English and the local language, Kinyarwanda. Counsellors underwent extensive training in the delivery of the FSI by the intervention developers, study investigators and local and international clinicians. A 2-week training period involved role play based learning of the central theory and practices of the intervention using a comprehensive intervention manual, as well as discussion of techniques for ensuring parent engagement, and strategies for facilitating family conversations via group practice and discussion. Counsellors worked in pairs when they met with their first families, and once they were comfortable with the intervention, they worked individually.

After initial training, investigators and Boston-based supervisors provided weekly phone supervision that included case presentation, group discussion, problem solving and support. Counsellors met with the Rwanda-based programme manager at least weekly to review successes and challenges in intervention delivery. An experienced clinical psychologist from the University of Rwanda provided additional local supervision.

Open trial

Participants

The inclusion criteria for families were residing in the Nyamirama Health Center's catchment area, having an adult HIV-positive caregiver of at least one school-aged child (aged 7–17 years) and caregivers' willingness to discuss HIV and AIDS during the course of the intervention (they were not required to have disclosed prior to enrolment). The exclusion criterion was severe crisis in the family including active suicidal ideation/attempts by any family members. All caregivers gave written consent for themselves and their children. All participating eligible children provided informed written assent. Twenty HIV-affected families (N = 28 caregivers) were enrolled in the open trial, of whom nine were dual-caregivers (two caregivers living in the home). Caregivers ranged from 30 to 70 years of age and were most frequently biological mothers and fathers followed by step-parents; three of the dual-caregiver families were serodiscordant couples. Eleven were single-caregiver families headed by women. Within the 20 families, 39 children (17 females) were eligible to participate. Children younger than 7 were not enrolled due to their decreased likelihood of being able to accurately self-report on assessments [41]. Children aged 5–6 and over 17 years who lived in the home were invited to participate in the intervention but were not assessed given the focus on school-aged children. Children could elect not to participate and their family was still eligible as long as at least one eligible child in the home agreed to participate. Participants received a modest gift after the final assessments consisting of local foods and basic home/school items.

Procedures

Recruitment

Families were recommended by the health centre's social worker from the current social work caseload in southern Kayonza District. Social workers identified families who met the inclusion criteria, described the study to caregivers, and asked whether the family might be interested in participating. Families were enrolled between October 2011 and August 2012. If caregivers agreed to be recruited, study staff met with the family in their home, explained the study and confirmed eligibility. Caregivers were first invited to give informed consent for their own participation and then for their children's participation. All eligible children (age 7–17 years) were invited to give informed assent independent of their caregiver (conducted separately). Once enrolled, families were randomly assigned to counsellors. All study procedures were approved by the Rwandan National Ethics Committee and the Harvard School of Public Health's Institutional Review Board.

Qualitative data collection

After completing the quantitative postassessments, all eligible children and caregivers completed an individual semi-structured interview to better understand their experiences with the FSI. Participant responses were recorded in research assistant notes and audiorecordings that were transcribed and translated into English. Qualitative analyses assessed participant satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the intervention and challenges or barriers to participation and were conducted following a multipart thematic analysis procedure. First, all transcripts were read thoroughly and initial themes related to the central research questions of feasibility, acceptability and barriers/facilitators to intervention were identified. Next, the team developed a codebook that was applied by two coders using the Dedoose software program [42].

Quantitative data collection

Comprehensive quantitative batteries assessing main study outcomes were administered immediately before (preassessment), immediately after (postassessment) and 6 months after (6-month follow-up) the FSI intervention. The caregiver who stated that he or she knew the child best, provided reports on the child's mental health and protective processes, the quality of the caregiver–child relationship, self-reports on his or her own social support and mental health, household reports on wealth and family demographics and whether children were on ART. Children self-reported on their own mental health and protective processes. The quantitative batteries were administered orally by bilingual (English/Kinyarwanda) Rwandan research assistants in Kinyarwanda using smartphones. In addition, after each FSI module, counsellors completed notes about participant reactions to the sessions and their own experience with delivering the material. All interviews and sessions were conducted in the families' homes.

Measures

Fidelity to the intervention

To assess fidelity to the intervention, counsellors kept detailed checklists on the content delivered (topic, role play, vignette or activity) for each module, and how well the family responded to the content. FSI Content Fidelity was scored as the percentage of expected FSI content that was delivered to families. The Quality of Content Delivery was scored as the mean rating of how well activities went (0, badly; 1, moderately; 2, well) for all completed activities.

Participant satisfaction

Participant satisfaction

The English qualitative transcripts were coded for statements describing participant satisfaction. Responses comprised three categories: 0, not satisfied; 1, satisfied; 2, very satisfied that was summed. Interrater reliability was good (Cohen's kappa [k] = 0.82).

Participant concerns

Participant concerns with, and barriers to, participation in the FSI were coded from the English qualitative transcripts following the same procedure as participant satisfaction. Participant concerns were expressions of negative experiences with, or feelings towards, the intervention. If during any statement, participants expressed concern, Participant Concern was scored as a `1', otherwise it was scored as `0'. Interrater reliability was good (k = 0.88).

Counsellor rating of participant satisfaction and comfort

After each module, counsellors responded on a 4-point scale (0, strongly disagree to 3, strongly agree) assessing participant satisfaction and comfort with the module. Mean scores for counsellor-rated participant comfort and satisfaction were calculated from the scores for each module.

Outcome measures

Measures of family protective factors and children's mental health were developed, adapted and validated in the local context in previous research [43]. Measures followed a rigorous translation protocol from English to Kinyarwanda [24,44].

Youth and family protective and risk factors

Family-level protective and risk processes included caregiver and youth reports of

-

(1)

Family connectedness: a 15-item scale derived from local qualitative data. Scoring was 0 (never) to 3 (every day). Internal consistency was excellent (α = 0.93).

-

(2)

Good parenting: a 16-item scale from local qualitative data. Scoring was 0 (never) to 3 (every day) (α = 0.92). Youth and caregivers reported on the youth's internal protective processes including

-

(3)

Perseverance/self-esteem: a 34-item scale of which 25 were from the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [45] and nine were from local qualitative data (α = 0.92)

-

(4)

Pro-social behaviour: A 20-item scale from local qualitative data (α = 0.90)

-

(5)

Harsh punishment: A 12-item (child version) and 13-item (caregiver version) version of the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey-Round 4 (MICS4) Child Discipline Household Survey [46]. Items were scored 0, no and 1, yes (α = 0.63 for child report, 0.61 for caregiver report).

-

(6)

Youth and caregivers also reported on their own social support: A 33-item scale of which 25 items were from the Inventory of Socially Supportive Behaviors (ISSB) [47] and eight were from local qualitative data (α = 0.92 for child report, 0.76 for caregiver report).

Youth mental health and functioning

Youth and their caregivers reported on the following measures of youth mental health:

-

(1)

Depression: An adapted 30-item scale [48] of which 20 comprised core items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CESDC) [49] with 10 additional items added from local qualitative data. Scoring was 0 (never) to 3 (often) (α = 0.95). To determine levels of diagnosable depression at baseline, a clinical cut-off of at least 30 (determined from a validity study in this population) [50] was applied to the 20 original CES-DC items.

-

(2)

Anxiety/depression: A 23-item scale, 16 of which were from the Youth Self-Report (YSR) internalizing subscale [51] and seven from local qualitative data (α = 0.93).

-

(3)

Irritability: A 27-item scale of which 21 were from the Irritability Questionnaire (IRQ) [52] and seven were from local qualitative data (α = 0.90).

-

(4)

Conduct problems: Youth Conduct Problems Scale-Rwanda Short Form (YCPS-RS), an 11-item scale from local qualitative data (α = 0.89).

-

(5)

Functional impairment was assessed with the 25-item WHO Disability Assessment Schedule for Children (WHODAS-Child) validated with Rwandan children [43] (α = 0.79).

Covariates

Covariates were youth sex and age, single-caregiver status and family wealth (as reported by the caregivers), which was derived from items from the Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey [53].

Quantitative data analysis

Analyses to assess child change over time in study outcomes were conducted using hierarchical linear modelling (HLM) [54,55]. The multilevel approach was selected because observations were clustered within individuals and families, and because the technique models all available data regardless of whether some individuals (individuals within a household or entire households) were missed at one time point. Family-level covariates included single or dual-caregiver status and wealth of the family; individual covariates included child age and sex. For all analyses, an alpha of 0.05 was used to identify statistically significant differences. Analyses were conducted in R [56].

Results

Participants

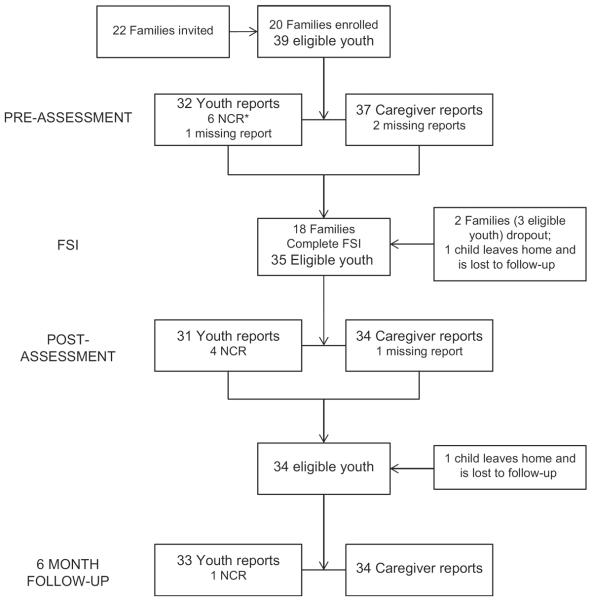

Thirty-nine youth between the ages of 7 and 17 years in 20 different families were enrolled in the study. Twenty-two families were invited to participate and two declined participation. In one enrolled family, one eligible child declined to participate. Over half of the families (N=11) were single, female-headed and nine families had both a male and female caregiver; the family structures were diverse with 10% intergenerational families (i.e. grand-children in the home) and 35% of families having either step-children or foster children living in the home. On average, children were 12.69 (SD=3.43) years old, and 21 (53.85%) were male. Four children were HIV-positive and were reported to be on antiretroviral therapy (ART) at the time of study. At preassessment, six children (ages 7–10 years) were deemed not cognitively ready to complete the self-report assessment. Eighteen of 20 families (90%) completed the intervention and all assessments (see Fig. 1). Overall attendance was excellent, with 97% of eligible caregivers and children attending all sessions. The main themes that arose during intervention sessions are reported in Table 3. The two families who dropped out of the intervention had difficulty with the time commitment.

Fig. 1. Participant flow chart.

NCR, not cognitively ready to complete assessments.

Table 3.

Common themes encountered in families during the intervention.

| Theme | N | Percentage of completed familiesa | Percentage of dual-caregiver families (N = 8) | Percentage of single-caregiver families (N=10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| References to the Genocide | 9 | 50 | 25 | 70 |

| Family conflicts or violence | 4 | 22 | 25 | 18 |

| Alcohol abuse | 3 | 17 | 25 | 9 |

| Death of a spouse or caregiverb | 12 | 67 | 75 | 55 |

| Caregivers having difficulties adapting HIV in the family | 6 | 33 | 63 | 9 |

| Children having difficulties adapting to caregiver's HIV | 10 | 56 | 50 | 55 |

| Family experiencing HIV stigma | 3 | 17 | 13 | 18 |

| Counselor supported disclosure | 5 | 28 | 13 | 40 |

| Difficulties schooling children (i.e. school dropout/failing, lacking money for materials or school fees) | 15 | 83 | 75 | 82 |

| Difficulties meeting basic needs (i.e. housing, food, clothes) | 8 | 44 | 25 | 55 |

Percentage is based on the number of families that completed the FSI (N=18).

Family reported the death of a prior spouse and/or caregiver to the children

Fidelity to the intervention

Counsellor self-reported fidelity to the intervention was high with a mean of 98.47% (SD=0.02, range 93–100) of the FSI content delivered to families. Counsellors rated the quality of the content delivery as very good, with almost all content delivery rated as going `Well' (mean=1.95, SD=0.06).

Participants' experiences and satisfaction

Postintervention qualitative interviews were conducted with all 26 caregivers and 32 of 35 youth in the 18 families who completed the intervention. Of the 58 participants, 57 (98.28%) indicated that they were satisfied or very satisfied with the FSI. Almost two-thirds of participants (65.52%) reported that they did not have any concerns with the FSI. Of those reporting concerns, reasons most frequently pertained to the time the intervention and assessments took and a desire for material support. One mother shared:

`It's really good to talk but …we need something to lift up my life, our life conditions. It is good to be unified and cooperate in the family even communicate in good ways but also we need another help. [referring to needs for material support]'

`Yes there were a few problems associated with getting the family together because some of the children were at school and it was hard for us to pick them from school sometimes, but most of the time his father picked them from school and it was ok'.

Some participants also mentioned that community members perceived the home-visiting team as bringing them material support that led to jealously `Yes community members always thought you had brought us things and money every time you came for the intervention … They are not happy thinking that you bring money for us'.

Above all, the FSI proved to be both acceptable and successful in working with families on the four core components. As one father shared, the FSI empowered him: `I got stronger. After the [FSI] sessions, I felt like no matter how hard life gets, one can always overcome the problems they face'. Another single-mother shared how the FSI allowed her to open up to her children about HIV and AIDS:

`I asked them [my children] what the most interesting thing was for them ever since [the counselor] came … My son says, “Mama the conversations about HIV and AIDS were very good”. So I also join them and we talk about it [HIV]'.

Promoting two-way communication between children and caregivers is a core FSI component and one child shared how the FSI helped him and his parents communicate more effectively:

`My family was unable to talk to me but when the counsellor came to talk to us, we were able to talk to our parents and we have been close to them and communicate without problems [now]'.

Children and their caregivers both expressed appreciation for the FSI and provided examples of how it helped bring family members closer and taught them how to communicate with one another.

Change in protective factors and youth mental health

According to caregivers, youth protective factors of family connectedness, good parenting, child pro-social behaviour and caregiver social support improved significantly from preintervention to postintervention, and changes were sustained and showed continued improvement at the 6-month follow-up. In addition, caregiver-reported youth perseverance/self-esteem was higher at 6-month follow-up than at preintervention. Youth-reported social support and parental use of harsh punishment also improved significantly from pre to postintervention and improvements were sustained at 6 months of follow-up. Caregiver-reported harsh punishment was also lower at 6-month follow-up than at preintervention (see Table 4 for complete results). The number of children who scored in the clinical range for depression decreased from five of 32 (15.63%) at baseline to four of 31 (12.90%) at postassessment, to three of 33 (9.09%) at follow-up. The number of children whom caregivers rated in the clinical range for depression decreased from five of 37 (13.51%) at baseline, to three of 34 (8.82%) at postassessment, to zero of 34 at follow-up. According to caregivers, youth-internalizing symptoms (depression, anxiety/depression and irritability) also improved from preintervention to 6-month follow-up. There were no reported improvements in youth conduct problems or functional impairment. Although youth self-reports of symptoms showed trajectories of improvement over time, they did not reach the P less than 0.05 level of significance. Such outcomes may be more fully captured in future trials with larger samples.

Table 4.

Estimated regression coefficients from mixed effects models.

| Posttreatment |

Six-month follow-up |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Estimate | t value | Effect size | Estimate | t value | Effect size |

| Family connectedness | ||||||

| Caregiver report | 0.290 | 2.250* | 0.514 | 0.539 | 4.326* | 0.954 |

| Child report | 0.133 | 1.324 | 0.259 | 0.068 | 0.666 | 0.132 |

| Good parenting | ||||||

| Caregiver report | 6.993 | 3.908* | 0.822 | 8.839 | 5.207* | 1.039 |

| Child report | 1.780 | 1.404 | 0.235 | 1.284 | 1.003 | 0.170 |

| Perseverance/self-esteem | ||||||

| Caregiver report | 6.981 | 1.925 | 0.383 | 15.534 | 4.342* | 0.853 |

| Child report | 0.979 | 0.267 | 0.051 | −4.536 | −1.227 | −0.236 |

| Pro-social behaviour | ||||||

| Caregiver report | 0.330 | 2.872* | 0.649 | 0.344 | 2.963* | 0.677 |

| Child report | 0.045 | 0.496 | 0.093 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.002 |

| Social support | ||||||

| Caregiver report | 21.157 | 4.083* | 0.956 | 27.804 | 5.387* | 1.256 |

| Child report | 11.414 | 2.010* | 0.447 | 5.777 | 1.010 | 0.226 |

| Depression | ||||||

| Caregiver report | −4.084 | −1.371 | −0.290 | −8.722 | −2.923* | −0.618 |

| Child report | −5.471 | −1.806 | −0.309 | −5.989 | −1.956 | −0.338 |

| Anxiety/Depression | ||||||

| Caregiver report | −2.359 | −1.231 | −0.274 | −5.505 | −2.866* | −0.640 |

| Child report | −0.604 | −0.426 | −0.065 | −2.849 | −1.988 | −0.305 |

| Irritability | ||||||

| Caregiver report | −0.171 | −1.900 | −0.385 | −0.350 | −3.880* | −0.788 |

| Child report | −0.172 | −1.882 | −0.32 | −0.156 | −1.681 | −0.288 |

| Conduct problems | ||||||

| Caregiver report | −0.992 | −1.019 | −0.218 | −0.573 | −0.587 | −0.126 |

| Child report | −1.656 | −1.548 | −0.268 | −1.808 | −1.682 | −0.292 |

| Functional impairment | ||||||

| Caregiver report | −0.430 | −0.193 | −0.042 | −3.559 | −1.586 | −0.346 |

| Child report | 0.121 | 0.127 | 0.027 | −0.352 | −0.368 | −0.078 |

| Harsh punishment | ||||||

| Caregiver report | −0.028 | −0.871 | −0.189 | −0.070 | −2.083* | −0.463 |

| Child report | −0.088 | −2.558* | −0.530 | −0.089 | −2.589* | −0.540 |

Caregivers reported on their own social support, but reported on their child or family for all other measures.

P<0.05.

Discussion

This open trial indicates initial feasibility and acceptability of the FSI for promoting improved caregiver–child relationships, family communication and reducing risks for emotional and behavioural problems in vulnerable children affected by HIV and AIDS in Rwanda. Our results indicate that caregiver-reported improvements in children's pro-social behaviour, family connectedness, good parenting and social support were sustained and strengthened from postintervention to 6-month follow-up. Caregiver-reported child perseverance/self-esteem also improved, and symptoms of depression, anxiety and irritability in children declined at 6-month follow-up. Caregiver and child-reported harsh punishment also decreased significantly at 6-month follow-up. These initial results will need to be further tested in well powered effectiveness trials.

Our results resonate with those of other family-focused interventions that have shown promise for HIV-prevention in South Africa [57] and for HIV-affected families in the United States [25,58,59] and Asia [60,61]. The FSI expands upon these important interventions by extending a focus to family-based mental health promotion for school-age children affected by HIV in rural sub-Saharan Africa using a family home visiting model. The home-visiting nature of the intervention enhances access by allowing counsellors to reach many vulnerable children at once and decreases barriers such as child care and transportation challenges that many vulnerable families face when trying to access healthcare or centre-based psychosocial interventions. As routine HIV services are increasingly available across many low-resource settings, in situations in which HIV-positive adults have children in the home, such FBPIs can act to strengthen parent–child relationships, provide accurate information on HIV and AIDS, help families draw from their own inherent resilience and better navigate both formal and informal support structures. In future research, the FSI model could be further adapted to integrate elements of early childhood stimulation, nutrition and hygiene to help expand the reach of early childhood development (ECD) interventions to vulnerable children and families through family-home visiting models.

In addition, this open trial served to refine the FSI on the basis of the experiences of both participants and the counsellors, which strengthened the quality of the FSI manual as well as intervention delivery tools for future implementation, evaluation and diffusion. Although results are promising, study limitations must be noted. Although counsellors reported that rates of participation were strong and that the intervention could be successfully delivered, we do not have independent measures of attendance or feasibility. Such data collection is essential in future trials of the FSI. In addition, as a feasibility trial, this research did not involve a control group and was not adequately powered to detect small changes over time. However, even with limited statistical power, our models detected significant changes both immediately posttreatment and at 6-month follow-up and successfully demonstrated the acceptability and feasibility of a home-visiting preventive intervention. Although initial results are promising, future research should investigate intervention effectiveness, costs and maintenance of effects longitudinally.

Conclusion

Children affected by caregiver HIV remain largely overlooked in the global response to the HIV and AIDS pandemic. FBPIs have an important role to play in reducing emotional and behavioural problems and improving overall functioning in families affected by HIV and AIDS. Interventions such as the FSI have much promise in sub-Saharan Africa and should be investigated further in effectiveness and implementation research.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R34 MH084679) and the Julie Henry Junior Faculty Development Fund of the Harvard School of Public Health. The work was made possible by the collaboration of the Honorable Minister of Health of Rwanda, Agnes Binagwaho and Yvonne Kayiteshonga of the Rwanda Biomedical Center/Ministry of Health. We are grateful to Robert Brennan of the Harvard School of Public Health for providing statistical expertise. Theresa Betancourt obtained funding, supported intervention development and interpretation of the data, and provided clinical supervision. Lauren Ng contributed significantly to writing and data interpretation and provided clinical supervision. Catherine Kirk oversaw intervention implementation and data collection and made significant intellectual contributions to the manuscript content. Morris Munyanah, Christina Mushashi, Charles Ingabire and Sharon Teta supported intervention development, data collection, intervention delivery and made significant intellectual contributions to intervention and manuscript content. William Beardslee developed the original intervention and supported adaptation to Rwanda, provided clinical supervision and contributed significant writing and revisions for intellectual context. Robert Brennan contributed to study concept and design, data analysis, interpretation of the data and drafting of the manuscript. Ista Zahn conducted data analyses and contributed to data interpretation. Sara Stulac, Felix Cyamatare and Vincent Sezibera supported clinical supervision during intervention delivery and contributed to intervention adaptation and writing.

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R34 MH084679) and the Julie Henry Junior Faculty Development Fund of the Harvard School of Public Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.UNAIDS . Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. UNAIDS; Geneva, Switzerland: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNICEF . Children and AIDS: fifth stocktaking report. UNICEF; UNAIDS; World Health Organization; UNFPA; UNESCO; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allison S. The role of families among orphans and vulnerable children in confronting HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa. In: Pequegnat W, editor. Family and HIV/AIDS: cultural and contextual issues in prevention and treatment. Springer Science + Business Media; Blue Bell, PA: 2012. pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doku P. Parental HIV/AIDS status and death, and children's psychological wellbeing. Int J Mental Health Syst. 2009;3:26. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-3-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cluver LD, Orkin M, Gardner F, Boyes ME. Persisting mental health problems among AIDS-orphaned children in South Africa. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53:363–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richter L. The impact of HIV/AIDS on the development of children [Monograph No 109] In: Pretoria PR, editor. A generation at risk? HIV/AIDS, vulnerable children and security in Southern Africa Ed. Institute of Security Studies; 2004. pp. 9–31. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forehand R, Jones DJ, Kotchick BA, Armistead L, Morse E, Morse PS, et al. Noninfected children of HIV-infected mothers: a 4-year longitudinal study of child psychosocial adjustment and parenting. Behav Ther. 2002;33:579–600. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makame V, Ani C, Grantham-McGregor S. Psychological well being of orphans in Dar El Salaam. Tanzania Acta Paediatr. 2002;91:459–465. doi: 10.1080/080352502317371724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy DA, Greenwell L, Mouttapa M, Brecht ML, Schuster MA. Physical health of mothers with HIV/AIDS and the mental health of their children. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27:386–395. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200610000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lester P, Jane Rotheram-Borus M, Lee S-J, Comulada S, Cantwell S, Wu N, et al. Rates and predictors of anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents of parents with HIV. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2006;1:81–101. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giaconia RM, Reinherz HZ, Silverman AB, Pakiz B, Frost AK, Cohen E. Traumas and posttraumatic stress disorder in a community population of older adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:1369–1380. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199510000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Courtois CA. Complex trauma, complex reactions: assessment and treatment. Psychol Trauma. 2008;S:86. [Google Scholar]

- 13.UNAIDS . Country report: Rwanda. United Nations General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS); Rwanda: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crowe S. Helping Orphans in Rwanda Build a Better Future. UNICEF; 2006. www.unicef.org/infobycountry/rwanda_31013.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith DN. The psychocultural roots of genocide. Legitimacy and crisis in Rwanda. Am Psychol. 1998;53:743–753. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.7.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rochat T, Mkwanazi N, Bland R. Maternal HIV disclosure to HIV-uninfected children in rural South Africa: a pilot study of a family-based intervention. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:147. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Visser M, Finestone M, Sikkema K, Boeving-Allen A, Ferreira R, Eloff I, et al. Development and piloting of a mother and child intervention to promote resilience in young children of HIV-infected mothers in South Africa. Eval Program Plann. 2012;35:491–500. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ministry of Gender Family Promotion . A situation analysis of orphans and other vulnerable children in Rwanda. Rwanda Go. Kigali; Rwanda: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daud A, Skoglund E, Rydelius P. Children and families of torture victims: transgenerational transmission of parents' traumatic experiences to their children. Int J Soc Welf. 2005;14:23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 20.UNAIDS . Country progress report: Rwanda. UNAIDS; Geneva, Switzerland: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farmer PE, Nutt CT, Wagner CM, Sekabaraga C, Nuthulaganti T, Weigel JL, et al. Reduced premature mortality in Rwanda: lessons from success. BMJ. 2013;346:f65. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rich ML, Miller AC, Niyigena P, Franke MF, Niyonzima JB, Socci A, et al. Excellent clinical outcomes and high retention in care among adults in a community-based HIV treatment program in rural Rwanda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59:e35–e42. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824476c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denison JA, McCauley AP, Dunnett-Dagg WA, Lungu N, Sweat MD. HIV testing among adolescents in Ndola, Zambia: how individual, relational, and environmental factors relate to demand. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21:314–324. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.4.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biddlecom A, Awusabo-Asare K, Bankole A. Role of parents in adolescent sexual activity and contraceptive use in four African countries. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;35:72–81. doi: 10.1363/ipsrh.35.072.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lee M, Leonard N, Lin YY, Franzke L, Turner E, et al. Four-year behavioral outcomes of an intervention for parents living with HIV and their adolescent children. AIDS. 2003;17:1217–1225. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200305230-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rochat TJ, Bland T, Coovadia H, Stein A, Newell ML. Towards a family-centered approach to HIV treatment and care for HIV-exposed children, their mothers and their families in poorly resourced settings. Future Virol. 2011;6:687–696. doi: 10.2217/fvl.11.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins PY, Holman AR, Freeman MC, Patel V. What is the relevance of mental health to HIV/AIDS care and treatment programs in developing countries? A systematic review. AIDS (London, England) 2006;20:1571. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000238402.70379.d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Betancourt TS, Meyers-Ohki S, Stevenson A, Ingabire C, Kanyanganzi F, Munyana M MC, et al. Using mixed-methods research to adapt and evaluate a family strengthening intervention in Rwanda. Afr J Trauma Stress. 2011;2:32–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Betancourt TS, Rubin-Smith J, Beardslee WR, Stulac S, Fayida I, Safren S. Understanding locally, culturally, and contextually relevant mental health problems among Rwandan children and adolescents affected by HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2011;iFirst:1–12. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.516333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Betancourt TS, Meyers-Ohki SE, Stulac SN, Barrera AE, Mushashi C, Beardslee WR. Nothing can defeat combined hands (Abashize hamwe ntakibananira): protective processes and resilience in Rwandan children and families affected by HIV/AIDS. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:693–701. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beardslee WR. Prevention and the clinical encounter. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68:521–533. doi: 10.1037/h0080361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beardslee WR, Gladstone TR, Wright EJ, Cooper AB. A family-based approach to the prevention of depressive symptoms in children at risk: evidence of parental and child change. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e119–e131. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.e119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beardslee WR, Salt P, Versage EM, Gladstone TR, Wright EJ, Rothberg PC. Sustained change in parents receiving preventive interventions for families with depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:510–515. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.4.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D'Angelo EJ, Llerena-Quinn R, Shapiro R, Colon F, Rodriguez P, Gallagher K, et al. Adaptation of the preventive intervention program for depression for use with predominantly low-income Latino families. Fam Process. 2009;48:269–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Podorefsky DL, McDonald-Dowdell M, Beardslee WR. Adaptation of preventive interventions for a low-income, culturally diverse community. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:879–886. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beardslee WR, Paez-Soto A, Herrera-Amighetti LD, Montero F, Herrera HC, Llerena-Quinne R, et al. Adaptation of a preventive intervention approach to strengthen families facing adversities, especially depression. Costa Rica: initial systems approaches and a case example. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2011;13:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sparrow J, Armstrong MI, Bird C, Grant E, Hilleboe S, Olson-Bird B, et al. Community-based interventions for depression in parents and other caregivers on a northern plains native American reservation. In: Sarche MC, Spicer P, Farrel P, Fitzgerald E, editors. American Indian and Alaska native children and mental health: development, context, prevention, and treatment. Praeger; Denver, CO: 2011. pp. 205–233. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beardslee WR, Versage EM, Wright EJ, Salt P, Rothberg PC, Drezner K, et al. Examination of preventive interventions for families with depression: evidence of change. Dev Psycho-pathol. 1997;9:109–130. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beardslee WR, Versage EM, Gladstone TR. Children of affectively ill parents: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:1134–1141. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beardslee WR, Wright EJ, Gladstone TRE, Forbes P. Long-term effects from a randomized trial of two public health preventive interventions for parental depression. J Fam Psychol. 2007;21:703–713. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riley AW. Evidence that school-age children can self-report on their health. Ambul Pediatr. 2004;4:371–376. doi: 10.1367/A03-178R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dedoose Version 4.5, web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC; Los Angeles, CA: 2013. www.dedoose.com. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scorza P, Stevenson A, Canino G, Mushashi C, Kanyanganzi F, Munyanah M, et al. Validation of the `World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule for Children, WHODAS-Child' in Rwanda. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Messam T, McKay MM, Kalogerogiannis K, Alicea S, Hope Committee Champ Collaborative Board MHHC adapting a family-based HIV prevention program for homeless youth and their families: the HOPE (HIV prevention Outreach for Parents and Early adolescents) Family Program. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2010;20:303–318. doi: 10.1080/10911350903269898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) Depress Anxiety. 2003;18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.UNICEF . Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS): household questionnaire. UNICEF; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barrera M, Sandler IN, Ramsay TB. Preliminary development of a scale of social support: studies on college students. Am J Commun Psychol. 1981;9:435–447. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steinberg AM, Brymer M, Decker K, Pynoos RS. The UCLA PTSD reaction index. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004;6:96–100. doi: 10.1007/s11920-004-0048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faulstich M, Carey MP, Ruggiero L. Assessment of depression in childhood and adolescence: an evaluation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC) Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:1024–1027. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.8.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Betancourt TS, Scorza P, Meyers-Ohki S, Mushashi C, Kayiteshonga Y, Binagwaho A, et al. Validating the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children in Rwanda. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:1284–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Achenbach TM, Dumenci L. Advances in empirically based assessment: revised cross-informant syndromes and new DSM-oriented scales for the CBCL, YSR, and TRF: comment on Lengua, Sadowksi, Friedrich, and Fischer (2001) J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:699–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Craig KJ, Hietanen H, Markova IS, Berrios GE. The irritability questionnaire: a new scale for the measure of irritability. Psychiatry Res. 2008;159:367–375. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) Rwanda demographic and health survey 2005. NISR, ORC Macro; Calverton, MD: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods. London: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singer J, Willett J. Applied longitudinal data analysis. Oxford University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 56.R Development Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bhana A, McKay MM, Mellins C, Petersen I, Bell C. Family-based HIV prevention and intervention services for youth living in poverty-affected contexts: the CHAMP model of collaborative, evidence-informed programme development. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13:S8. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-S2-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Stein JA, Lester P. Adolescent adjustment over six years in HIV-affected families. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lee MB, Gwadz M, Draimin B. An intervention for parents with AIDS and their adolescent children. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1294–1302. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li L, Ji G, Liang L, Ding Y, Tian J, Xiao Y. A mutilevel intervention for HIV-Affected families in China. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:1214–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li L, Liang L, Lee S, Iamsirithawron S, Rotherham-Borus Wan. Efficacy of an intervention for families living with HIV in Thailand: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:1276–1285. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0077-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]