Abstract

Objective:

According to the ‘‘vascular’’ theory, arterial overflow in the superior hemorrhoidal arteries would lead to dilatation of the hemorrhoidal venous plexus. Hemorrhoid laser procedure (LHP) is a new laser procedure for outpatient treatment of hemorrhoids in which hemorrhoidal arterial flow feeding the hemorrhoidal plexus is stopped by laser coagulation.

Aim:

Our aim was to compare the hemorrhoid laser procedure with open surgical procedure for outpatient treatment of symptomatic hemorrhoids.

Material and method:

A comparison trial between hemorrhoid laser procedure or open surgical hemorrhoidectomy was made. This study was conducted at Aloka hospital in Kosovo. Patients with symptomatic grade III or grade IV hemorrhoids with minimal or complete mucosal prolapse were eligible for the study: 20 patients treated with the laser hemorrhoidoplasty, and 20 patients–with open surgery hemorrhoidectomy. Operative time and postoperative pain with visual analog scale, were evaluated.

Results:

A total number of 40 patients (23 men and 17 women, mean age, 46 years) entered the trial. Significant differences between laser hemorrhoidoplasty and open surgical procedure were observed in operative time and early postoperative pain. There was a statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding the early postoperative period: 1 week, 2 weeks, 3 weeks and 1 month after respective procedure (p<0.01). The procedure time for LHP was 15.94 min vs. 26.76 min for open surgery (p<0.01).

Conclusion:

The laser hemorrhoidoplasty procedure was more effective than open surgical hemorrhoidectomy. Postoperative pain and duration time are only two indicators for this difference between there procedures.

Keywords: laser hemorrhoidoplasty, open surgery, pain, duration time

1. INTRODUCTION

Hemorrhoidal disease is ranked first amongst diseases of the rectum and large intestine, and the estimated worldwide prevalence ranges from 2.9% to 27.9%, of which more than 4% are symptomatic (1, 2). Approximately, one third of these patients seek physicians for advice. Age distribution demonstrates a Gaussian distribution with a peak incidence between 45 and 65 years with subsequent decline after 65 years (3, 4). Men are more frequently affected than women (5). The anorectal vascular cushions along with the internal anal sphincter are essential in the maintenance of continence by providing soft tissue support and keeping the anal canal closed tightly. Hemorrhoids are considered to be due to the downward displacement suspensory (Treitz) muscle (6, 7). The treatment options for symptomatic hemorrhoids have varied over time. Measures have included conservative medical management, non-surgical treatments and various surgical techniques. The various non-surgical treatments include rubber band ligation (RBL), injection sclerotherapy, cryotherapy, infrared coagulation, laser therapy and diathermy coagulation; all of which may be performed as out patient procedures without anaesthesia. These nonsurgical methods are considered to be the primary option for grades one to three (grade I-III) hemorrhoids (8). If conservative measures fail to control symptoms, patients may be referred to a surgeon for operative management. The indications for the surgical treatment include the presence of a significant external component, hypertrophied papillae, associated fissure, extensive thrombosis or recurrence of symptoms after repeated RBL. The technique employed may be open (Milligan–Morgan) or closed (Ferguson) and the instruments used are scalpel, scissor, electrocautery or laser. Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy is the gold standard and frequently performed procedure in the United Kingdom (9). Post hemorrhoidectomy pain is the commonest problem associated with the surgical techniques. The other early complications are urinary retention (20.1%), bleeding (secondary or reactionary) (2.4%–6%) and subcutaneous abscess (0.5%). The long-term complications include anal fissure (1% -2.6%), anal stenosis (1%), incontinence (0.4%), fistula (0.5%) and recurrence of hemorrhoids (10, 11). The aim of this study was to compare pain and duration time of intervention between of the two methods, laser hemorrhoidoplasty (LHP) and surgical open hemorrhoidectomy.

2. MATERIAL AND METHOD

In this comparative and prospective study 40 patients were included, of which, 20 patients were treated with laser hemorhoidoplasty method and 20 patients were treated with open surgical hemorrrhoidectomy. Patients were allocated in different groups, according to the stage of hemorrhoids: patients with stage III and minimal prolapse of mucosa were treated with LHP and patients with stage IV and prolapse, with open surgical method. This study was performed in ALOKA surgical center in Kosovo, from January 2012 to June 2014. After a detailed physical examination and proctoscopy, the laser procedure was performed with Biolitec. With the patient in the lithotomy position, a dedicated disposable proctoscope with a diameter of 23 mm was inserted in the anal canal. Laser shots were delivered with a 980-diode laser through a 1000-nm optic fiber in a pulsed fashion to reduce undesired degeneration of periarterial normal tissue. The depth of shrinkage can be regulated by the power and duration of the laser beam.

Through a 1000-micron optic fiber, five laser shots generated at a power of 13 W with duration of 1.2 s each and a pause of 0.6 s caused shrinkage of tissues to the depth of approximately 5 mm. This procedure was performed as an outpatient procedure. No bowel preparation was required. Two enemas were administered 2 hours before the intervention. Others, 20 patients were treated with open surgical hemorroidectomy in the local anesthesia. Patients were discharged within 4 to 12 hours, and were followed for 2 to 6 months for healing progress and complications. The patients were followed for the level of postoperative pain and duration of operation. Postoperative pain was recorded by using a 10-point visual analog scale (VAS) on which 0 represents no pain and 10 represents the worst pain imaginable. VAS protocol was followed up after 1 week, 2 weeks, 3 weeks, 1 month, 2 months and 6 months. The duration of intervention was recorded in minutes. The data were analyzed with statistical tests and presented with respective tables and graphics.

3. RESULTS

The LHP procedure was performed on 20 consecutive patients which had symptomatic grade III hemorrhoids with moderate mucosal prolapse at proctoscopy and a medical history of rare episodes of prolapse manual reduction, with mean age 47 ± 12.6 (range, 24–70) years. There were 11 men and 9 women. The open surgical procedure was performed on 20 patients which had symptomatic grade IV hemorrhoids and with complete prolapse and no response to manual reduction, with mean age 49 ± 12.3 (range 28-72) years. There were 12 men and 8 women.

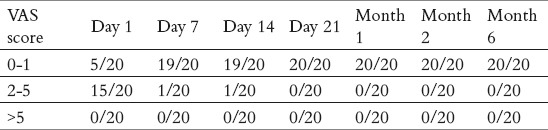

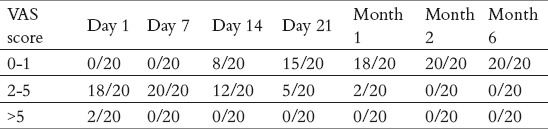

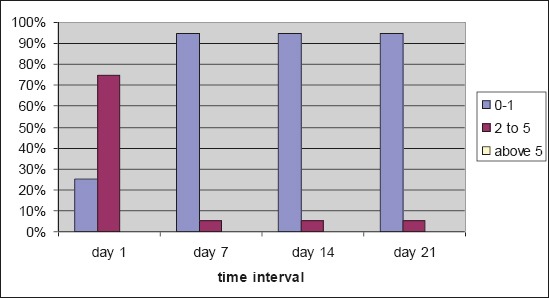

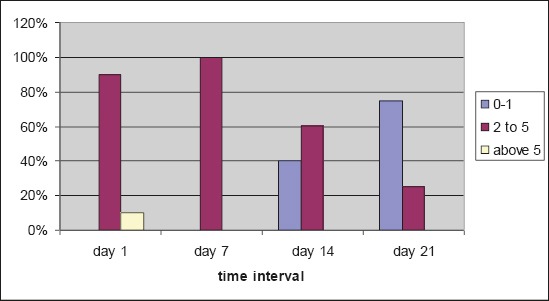

As far as pain is concerned, early postoperative pain is dominantly lower in the LHP group compared with surgical group. The same values also resulted for the period of one month. These results are presented in tables 1,2 and in figures 1,2.

Table 1.

Pain presentation by VAS score in the LHP group

Table 2.

Pain presentation by VAS score in the surgical group

Figure 1.

Pain presentation by VAS score in the LHP group

Figure 2.

Pain presentation by VAS score in the surgical group

The mean operative time was 15.94 ± 3.5 min in the LHP group and 26.76 ± 5.8 min (p<0.01). No major adverse effects or complications were reported. Bleeding was observed in one case (the patient was taking aspirin). In one case surgical hemostasis was necessary. Minor pain that required medication was reported in three cases, one in the LHP group and two in open surgery. No blood transfusions were needed in any of cases.

4. DISCUSSION

The need for treatment for hemorrhoids is primarily based on the subjective perception of severity of symptoms and the assignment of treatment is decided on the traditional classification of hemorrhoids (12), which is not connected to the severity of symptoms. Multiplicity of treatment modalities has added confusion in decision about the treatment method. The question of the optimal treatment technique remains unanswered despite most of the techniques in use being subjected to randomized evaluation. Generally an uncomplicated hemorrhoidectomy is satisfactory on non-surgery or operation for both, patient and surgeon (13). In a study of the university of Sao Paolo, Brazil, they stated that laser hemorrhoidectomy had the advantages of being haemostatic, bactericidal, fast healing, not affecting neighboring structures, less postoperative complications and less hemorrhage and stenosis (14, 15). Open surgical hemorrhoidectomy is the most widely used procedure in the surgical management of hemorrhoids. However, hemorrhoidectomy is associated with significant complications including pain, bleeding and wound infection which can result prolonged hospital stay (16). We found that the pain scores were significantly lower in the LHP group compared with open hemorrhoidectomy procedure group, in the early postoperative period after VAS score was 5 vs. 0 for score 0-1, 15 vs. 18 for score 2-5 and 0 vs. 2 for score above 5 in the respective groups. Postoperative pain is the most important complication that disturbs our patients and makes them reluctant to surgery. In our study, postoperative pain during the first month after both procedures, was significantly lesser in the laser hemorroidectomy compared with conventional open surgical hemorrhoidectomy (p<0.05). Our study showed that laser hemorrhoidoplasty is a safe procedure associated with less postoperative pain. Laser hemorrhoidectomy is associated with lesser duration time compared with open surgical hemorrhoidectomy, which is satisfactory for symptomatic hemorrhoidal patients with III or IV stage (15.94 vs. 26.76 min and p<0.01).

5. CONCLUSION

In summary, laser hemorrhoidoplasty procedure is more preferred in comparison with conventional open surgical hemorrhoidectomy. Postoperative pain is significantly lesser in laser procedure compared with surgical procedure (p<0.05). Duration time is significantly shorter in laser procedure (p<0.01).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: NONE DECLARED.

REFERENCES

- 1.Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A. The prevalence of hemorrhoids and chronic constipation: an epidemiological study. Gastroenterology. 1990;98(2):380–386. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90828-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogozina VA. Hemorrhoids. Eksperimental’ Naia i Klinicheskaia Gastroenterologiia. 2002;4:93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A. The prevalence of hemorrhoids and chronic constipation: an epidemiological study. Gastroenterology. 1990;98(2):380–386. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90828-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parks AG. De Hemorrhoids. A study in surgical history. Guy's Hospital Report. 1955;104:135–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keighley MRB. Vol. 1. WB Saunders publishers; 1993. Surgery of Anus, Rectum and Colon. 1; pp. 295–298. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas PA, Fox TA, Jr, Haas GP. The Pathogenesis of hemorrhoids. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 1984;27(7):442–450. doi: 10.1007/BF02555533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomson WHF. The nature of Hemorrhoids. British Journal of Surgery. 1975;62(7):542–552. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800620710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacRae HM, McLeod RS. Comparison of Hemorrhoidal Treatment Modalities. A meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38(7):687–694. doi: 10.1007/BF02048023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monson JRT, Mortenson NJ, Hartley J. Procedures for Prolapsing Hemorrhoids (PPH) or Stapled Anopexy. Consensus Document for Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. ACPGBI. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bleday R, Pena JP, Rothenberger DA, Goldberg SM, Buls JG. Symptomatic Hemorrhoids: Current Incidence and Complications of Operative Therapy. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 1992;35(5):477–481. doi: 10.1007/BF02049406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sardinha TC, Corman ML. Hemorrhoids. The Surgical clinics of North America. 2002;82(6):1153–1167. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(02)00082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goligher J, Duthie H, Nixon H. London: Baillière Tindall; 1984. Surgery of the Anus Rectum and Colon. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salfi R. A new technique for ambulantory hemorrhoidal treatment Doppler-guided laser photocoagulation of hemorrhoidal arteries. Coloproctology. 2009;31:99–103. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chia YW, Darzi A, Speakman CT, Hill AD, Jameson JS, Henry MM. Department of Surgery, Central Middlesex Hospital, London, UK Int. J Colorectal Dis. 1995;1011:22–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00337581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laurie Barcly. Best option for evaluating and treating hemorrhoids. BMJ. 2008 Feb 25;336:380–383. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milligan ET, Morgan CN, Jones LE, Officer R. Surgical anatomy of the anal canal and the operative treatment of hemorrhoids. Lancet. 1937;2:1119–1124. [Google Scholar]