Abstract

Background

Targeted therapy, using biomarkers to assess disease activity in ulcerative colitis (UC), has been proposed.

Objective

The objective of this study was to evaluate whether pharmacological intervention guided by fecal calprotectin (FC) prolongs remission in patients with UC.

Methods

A total of 91 adults with UC in remission were randomized to an intervention group or a control group. Analysis of FC was performed monthly, during 18 months. A FC value of 300 µg/g was set as the cut-off for intervention, which was a dose escalation of the oral 5-aminosalicylate (5-ASA) agent. The primary study end-point was the number of patients to have relapsed by month 18.

Results

There were relapses in 18 (35.3%) and 20 (50.0%) patients in the intervention and the control groups, respectively (p = 0.23); and 28 (54.9%) patients in the intervention group and 28 (70.0%) patients in the control group had a FC > 300 µg/g, of which 8 (28.6%) and 16 (57.1%) relapsed, respectively (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Active intervention significantly reduced relapse rates, although no significant difference was reached between the groups overall. Thus, FC-levels might be used to identify patients with UC at risk for a flare, and a dose escalation of their 5-ASA agent is a therapeutic option for these patients.

Keywords: 5-Aminosalicylate, biomarker, calprotectin, fecal calprotectin, randomized controlled study, relapse rate, ulcerative colitis

Introduction

Pharmacological treatment of ulcerative colitis (UC) is traditionally divided into treatment of active disease and treatment to maintain remission. Active UC of mild to moderate severity should preferably be treated with a 5-aminosalicylate (5-ASA) compound, given orally, topically or in combination, depending on disease distribution and severity.1 A dose-response effect of 5-ASA has been shown to induce remission in UC.1–5 Likewise, an oral 5-ASA agent is the first choice of treatment to maintain remission in UC.1 Even though several studies report a dose-response effect of 5-ASA to maintain remission, the documentation is not as robust as it is for induction of remission in active disease.6–8 Still, dose escalation of 5-ASA is one of several options when the maintenance treatment must be improved.1 Annually, up to 50% of patients with UC suffer a relapse, despite ongoing maintenance treatment.9,10

In 1992, Røseth et al.11 introduced a method for quantification of calprotectin in feces and found it useful as a biomarker of intestinal diseases, especially as a sensitive marker of disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Thereafter, fecal calprotectin (FC) was evaluated in numerous studies and it has been shown to be a useful tool in the diagnosis of IBD and to evaluate disease activity and response to therapy in IBD.12–14 Furthermore, FC was assessed as a marker to predict the disease course in IBD.15–17 In these studies, patients with IBD in clinical remission were included for evaluation of the clinical course during 1 year. The results are strikingly consistent: Patients with elevated values of FC at inclusion have an increased risk of disease recurrence over the year to come, as compared to patients with normal or only slightly elevated levels of FC. This result is consistent with previous reports of normal levels of FC predicting mucosal healing with high probability, and that mucosal healing has a great impact on the clinical course of IBD.18–20 Accordingly, a novel treatment strategy was proposed: To use FC levels to guide treatment in patients with IBD, to achieve sustained remission.15,17 Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate whether monitoring of FC on a regular basis, with dose escalation of oral 5-ASA in patients with increased calprotectin levels, has an impact on the clinical course in patients with UC.

Patients and methods

Adult patients with UC in clinical remission, but with at least one flare-up during the previous year, were eligible for this open-label, prospective, randomized, controlled study and they were followed for 18 months. The patients were recruited from five gastroenterology units in Western Sweden. All patients were on maintenance treatment with an oral 5-ASA preparation not exceeding 2.4 g Asacol® (mesalazine, Tillots Pharma, Rheinfelden, Switzerland), 2 g Pentasa® (mesalazine, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Saint-Prex, Switzerland) or 4.5 g Colazid® (balsalazide, Almirall, Barcelona, Spain). Concomitant treatment with an immunomodulating agent was allowed if that dosage had been stable for at least 3 months prior to inclusion in the study. However, patients on anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy, corticosteroids or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) were excluded, as were patients with a prior colon resection, pregnant patients and patients with comorbid disease that might affect their ability to comply with the study protocol. All patients provided written informed consent, according to the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board at the University of Gothenburg.

Study procedures

Upon inclusion in the study, patient demographic data and disease characteristics were collected and the disease activity was evaluated according to the Mayo score.3 Remission was defined as a Mayo score ≤ 2, with no single variable >1. A flexible sigmoidoscopy was performed within 2 weeks from the inclusion date. Health-related quality of life was assessed with the validated Short Health Scale (SHS).21 This is a four-item questionnaire with a 100 mm visual analogue scale for the responses to each of the four questions (Table 2). The results are presented as four specific scores, and not an overall score.

Table 2.

The Short Health Scale for assessment of quality of life

| Questions and corresponding answers (visual analogue scale) |

|---|

| How severe are the symptoms you suffer from your bowel disease? |

| No symptoms 0——————–100 Very severe symptoms |

| Do your bowel problems interfere with your activities in daily life? |

| Not at all 0——————–100 Interfere to a very high degree |

| How much worry does your bowel disease cause? |

| No worry 0——————–100 Constant worry |

| How is your general feeling of well-being? |

| Very good 0——————–100 Dreadful |

Eligible patients were randomly assigned in a 3:2 ratio to either an intervention group or a control group. The randomization was performed in blocks of 10 subjects, using the web-based Research. Randomizer (www.randomizer.org). To conceal the random allocation sequence, sealed envelopes were used. The patients were included in the study by the local investigator or the study’s principal investigator; and once each patient was randomized, this became an open-labeled study.

All patients delivered a stool sample within 2 weeks of their inclusion. Thereafter, the patients sent a stool sample, a filled-in SHS form and details of their current medication, using the regular mail monthly, for 18 months.

We excluded patients whom were randomized to the intervention group and whom delivered less than nine samples during the study period. The patients were informed not to change any treatment themselves, but to contact their outpatient clinic if bowel symptoms occurred, to confirm a possible flare-up. In case of a flare-up, the appropriate treatment, in accordance to conventional practice, was prescribed;1 thus, the treatment of a flare-up was not predetermined in the study protocol.

Intervention

A value of 300 µg/g of calprotectin in feces was set as the cut-off for beginning an intervention.

Patients randomized to the intervention group with a calprotectin value >300 µg/g in a stool sample were immediately requested to deliver another stool sample, within 1 week. Provided the analysis of this second sample confirmed a calprotectin value above the cut-off level, we performed a dose escalation of the 5-ASA preparation. Accordingly, we increased the dosage of Asacol®, Pentasa® or Colazid® to 4.8 g, 4.0 g and 6.75 g, respectively. In patients reporting adverse events after the dose escalation, the dosage was adjusted to be maximally tolerable. Thereafter, the patients continued to send a stool sample to the clinic every month during the study period. The high dose of the 5-ASA agent was maintained until the FC value was <200 µg/g, but for at least 3 months.

The primary outcome variable was the number of patients to have relapsed by month 18. A relapse was defined as an increase in symptoms, consistent with UC, and with sufficient severity to justify a change in medical treatment. Secondary outcome variables were: the time to first relapse, the need for additional medication like corticosteroids and immunomodulators, and quality of life.

Laboratory analyses

Approximately 2–3 g of feces were collected, placed in a plastic tube (Faeces Tube; Sarstedt, Nürnbrecht, Germany), sent to the clinic and upon receipt, immediately frozen and stored at – 70℃ until analysis. The samples were analyzed within 1 week after arrival to the clinic. We determined the FC concentrations using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Calprotectin ELISA; Bühlmann Laboratories AG, Basel, Switzerland) with a monoclonal capture antibody that was specific for calprotectin, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. According to the manufacturer, the normal range for FC is <50 µg/g.

The laboratory technicians whom were analyzing the stool samples were blinded to the randomization and to the patients’ clinical status.

Statistical analyses

In our control group, we assumed a 45% rate of relapse.9,10 Based on the available data from trials on induction and maintenance of remission with oral 5-ASA agents, and the aim to assess a new treatment strategy with clinical usefulness, we assumed a 20% rate of relapse in the active intervention group.2,3,5,8,22 With these assumptions and 80% power at a 5% significance level, we had to evaluate 130 patients, randomized in a 3:2 proportion for the final analyses. If the dropout rate was 10%, about 150 patients would have had to be included; however, due to long patient recruitment times, we completed enrolment after inclusion of 109 patients.

FC levels are presented as the median and the interquartile range (IQR). The other continuous variables are shown as the mean ± SD. Categorical variables are presented as percentages. The calprotectin values were not normally distributed; therefore, we used the Mann-Whitney U test to compare differences between the two groups. We used the Student’s t-test to compare normally-distributed continuous values, and the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test to compare categorical variables. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to derive time-to-relapse curves and statistical significance was determined using the log rank test. To compare the SHS quality of life questionnaires, the median scores on the visual analogue scales for each of the four questions were calculated; and then we used the Mann-Whitney U test to compare differences between the two groups. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

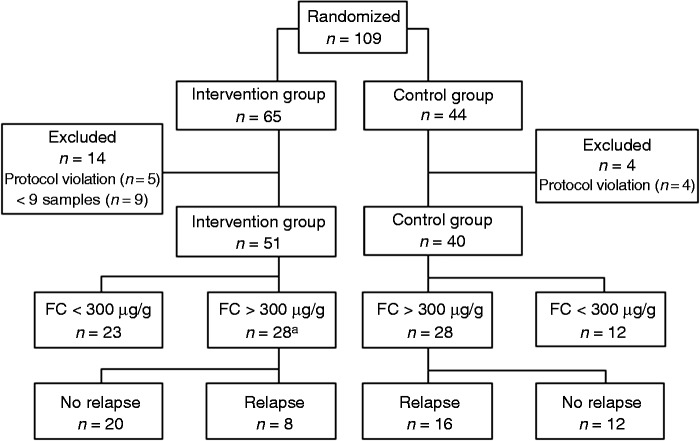

From August 2009 to December 2012, 109 patients were included. Eighteen patients were excluded (Figure 1). Another patient terminated his participation after the first relapse. Thus, 91 patients, 51 in the intervention group and 40 in the control group, were included in the primary outcome and the time-to-relapse analyses; and 90 patients were included in the remaining analyses. Baseline characteristics were similar in the two groups (Table 1). The mean time in remission prior to inclusion was 5.4 (SD 3.4) months in the intervention group and 5.6 (SD 3.0) months in the control group (p = 0.77). The concentrations of FC at inclusion were similar in the two groups: 66 µg/g (IQR 37–371) and 113 µg/g (IQR 58–380) in the intervention and control groups, respectively (p = 0.32).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition and outcome of the study population.

aIn patients with a calprotectin value >300 µg/g, we performed a dose escalation of the 5-ASA agent.

5-ASA: 5-aminosalisylate; FC: fecal calprotectin

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 91 patients with UC in remission

| Parameter | Intervention (n = 51) n (%) | Control (n = 40) n (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) age | 41.0 (21–67) | 41.5 (18–69) | 0.57 |

| 18–50 yr | 34 (66.7) | 31 (77.5) | |

| >50 yr | 17 (33.3) | 9 (22.5) | |

| Sex | 0.73 | ||

| Male | 20 (39.2) | 18 (45.0) | |

| Female | 31 (60.8) | 22 (55.0) | |

| Smoking history | 0.85 | ||

| Never smoked | 27 (52.9) | 18 (45.0) | |

| Used to smoke | 20 (39.2) | 18 (45.0) | |

| Currently smokers | 3 (5.9) | 3 (7.5) | |

| Taking snuff | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.5) | |

| Disease extent | 0.48 | ||

| Proctitis | 3 (5.9) | 2 (5.0) | |

| Left-sided colitis | 29 (56.9) | 18 (45.0) | |

| Extensive colitis | 19 (37.3) | 20 (50.0) | |

| Duration of disease | 0.52 | ||

| <1 yr | 2 (3.9) | 5 (12.5) | |

| 1–5 yrs | 21 (41.2) | 14 (35.0) | |

| 6–10 yrs | 11 (21.6) | 9 (22.5) | |

| >10 yrs | 17 (33.3) | 12 (30.0) | |

| Treatment at inclusion | 0.12 | ||

| Sulfasalazine | 0 (0) | 1 (2.5) | |

| Mesalazine | 46 (90.2) | 39 (97.5) | |

| Balsalazide | 5 (9.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Immunomodulators | 11 (21.6) | 5 (12.2) | 0.40 |

| Baseline Mayo score | 0.66 | ||

| Mayo score 0 | 36 (70.6) | 29 (72.5) | |

| Mayo score 1 | 7 (13.7) | 3 (7.5) | |

| Mayo score 2 | 8 (15.7) | 5 (12.5) | |

| Mayo endoscopic subscore | 1.00 | ||

| 0 (Normal) | 42 (82.4) | 31 (77.5) | |

| 1 | 9 (17.6) | 6 (15.0) | |

| Relapsesa | |||

| 1 | 38 (74.5) | 34 (85.0) | 0.34 |

| >1 | 13 (25.5) | 6 (15.0) |

Number of relapses during the year prior to inclusion.

yr: year

Altogether, the patients delivered 800 (mean, 15.7 per patient) and 554 (13.8 per patient) stool samples in the study’s intervention and control groups, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.91) found in the median levels of calprotectin between the groups, in all these samples (82 µg/g (IQR 34–310) versus 86 µg/g (IQR 37–278)).

At inclusion, there were 80 (87.9%), 5 (5.5%), 5 (5.5%) and 1 (1.1%) patients whom were treated with Asacol (1.6–2.4 g), Pentasa (1.0–2.0 g), Colazid (2.25–4.5 g) and sulfasalazine (1.5 g), respectively.

Intervention and relapse rates

In 28 out of 51 patients (54.9%) within the intervention group, the FC levels increased to >300 µg/g in at least one of the stool samples delivered monthly, which was confirmed in a new sample within a week. In those 28 patients, intervention (i.e. dose escalation of the 5-ASA agent) was accomplished. In the control group, 28/40 (70%) of the patients had at least one calprotectin value >300 µg/g (Figure 1).

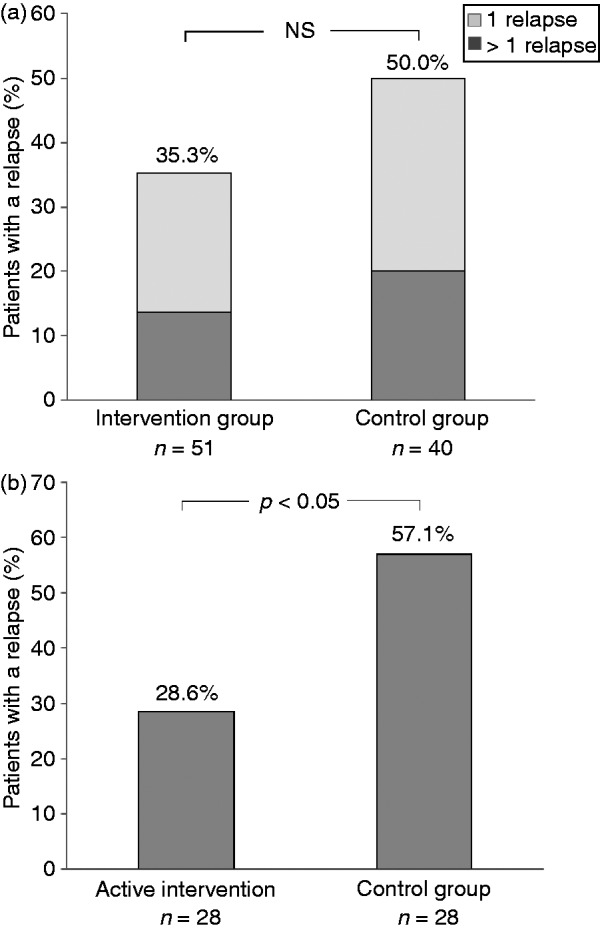

As shown in Figure 2(a), 18 out of 51 patients (35.3%) in the intervention group and 20 out of 40 (50.0%) in the control group had experienced at least one relapse by month 18 (p = 0.23). Overall, patients with a mild endoscopic inflammation (Mayo score 1) at inclusion did not relapse more frequently than those with a normal sigmoidoscopy (p = 0.91). The relapses were verified with endoscopy in 15 patients (83.3%) in the intervention group and in 10 patients (50.0%) in the control group (p = 0.07).

Figure 2.

(a) Proportion of patients with UC and at least one disease relapse. The patients in the intervention group performed a dose escalation of their ongoing 5-ASA treatment, if the value of FC in the monthly collected stool samples was >300 µg/g. More than one relapse occurred in 7/50 (14.0%) and 8/40 (20%) of patients in the two groups, respectively (p = 0.61). (b) Proportion of patients with at least one relapse, among the patients whom were actually dose-escalating the 5-ASA agent in the intervention group (n = 28), compared with patients in the control group, with FC > 300 µg/g (n = 28).

5-ASA: 5-aminosalisylate; FC: fecal calprotectin; NS: not significant; UC: ulcerative colitis

For 10 of the 18 patients (55.6%) with a relapse in the intervention group, the calprotectin level did not reach the cut-off value before they relapsed. For nine of these patients, the calprotectin levels in stool samples delivered approximately 1 month before the flare were <100 µg/g and for one patient, the level was 335 µg/g; however, for this patient, the second sample provided within a week did not confirm a value above the cut-off (it was 143 µg/g).

As shown in Figure 2(b), 8 out of 28 patients (28.6%) with active intervention relapsed, whereas 16 out of 28 patients (57.1%) in the control group with a calprotectin concentration >300 µg/g experienced a relapse (p < 0.05). The median time from dose escalation to onset of symptoms in the eight patients whom suffered a relapse despite the intervention, was 6 weeks (range 2–30).

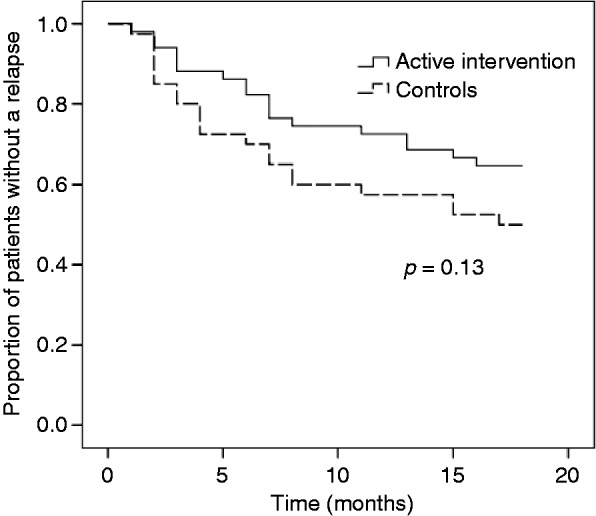

In 18 of 28 (64.3%) patients, their FC value fell from >300 µg/g at the time of dose escalation of the 5-ASA agent, to <200 µg/g after the intervention. The time to first relapse was 14.2 ± 5.9 versus 12.1 ± 6.9 months (mean ± SD) in the intervention and control groups, respectively (p = 0.13). Figure 3 shows the survival curves for the two groups. Despite the clearly separated curves, statistical significance was not achieved.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier time-to-first-relapse curves for patients with UC in the active intervention group and the control group. Active intervention meant a dose escalation of the 5-ASA agent being given, when the value of FC exceeded the predetermined cut-off level 300 µg/g.

FC: fecal calprotectin; UC: ulcerative colitis

At inclusion, the median time in remission was 5 months. Relapse rates were similar for the 27 out of 55 patients in remission for ≤5 months and for those 11 out of 36 patients in remission for >5 months (p = 0.12). Among the patients in remission ≤5 months prior to study enrollment, the levels of FC at inclusion were similar (p = 0.47) in those with a relapse and in non-relapsing patients (72 µg/g (IQR 42–372) versus 163 µg/g (IQR 38–621)).

Treatment

No patient developed a severe exacerbation requiring hospitalization over the 18-month period, nor did any patient start biological treatment. However, one patient in each group did start treatment with an immunomodulating agent. No significant differences in treatment were demonstrated between the groups (Table 3). Five patients, including three in the intervention group, reported headache and/or nausea due to the high-dose 5-ASA treatment.

Table 3.

Change in treatment owing to symptomatic relapse in each group of patients with UC

| Intervention n (%) | Control n (%) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral treatment | |||

| High-dose 5-ASAa | 16 (32.0) | 18 (45.0) | 0.30 |

| Corticosteroids | 9 (18.0) | 6 (15.0) | 0.92 |

| Topical treatment | |||

| 5-ASA | 13 (26.0) | 9 (22.5) | 0.89 |

| Corticosteroids | 6 (12.0) | 5 (12.5) | 1.00 |

Dose escalation because of a clinical relapse.

5-ASA: 5-aminosalicylate; UC: ulcerative colitis

Quality of life

To assess quality of life during the study period, the SHS four-item questionnaire was filled out monthly. We found no statistically significant differences between the two groups, for any of the four questions.

Discussion

Because several studies show that asymptomatic patients with UC and high values of FC are at increased risk of a disease relapse, we performed an interventional study to evaluate if FC-guided dosing of the 5-ASA agent could reduce this risk.15,16,23 Although the present study did not demonstrate statistically significant differences in overall relapse rates, we demonstrated that patients with active intervention experienced fewer disease relapses, as compared with patients in the control group with corresponding calprotectin levels. Thus, our results indicate that calprotectin levels may guide 5-ASA dosing, to avoid a symptomatic flare.

This approach, with targeted medical therapy using calprotectin to identify patients with UC at impending risk of a flare, and to optimize treatment for those before symptoms appear, is new. In a very recent trial by Osterman et al.24 a similar concept was presented; however, we preferred to monitor our patients over time and to maintain the current 5-ASA agent, instead of changing regimen. We also excluded patients with previous anti-TNF therapy, to achieve a more uniform group of patients.

A novel approach to therapy was evaluated and details of the design of a study like this have to be taken into consideration. When this study was initiated, the best cut-off values for prediction of a flare were reported to be 130–400 µg/g.15,23,25–27 Furthermore, in a study by Maiden et al.,28 the cut-off of 250 µg/g was successfully used to reduce relapse rates in patients treated with white cell apheresis. Our decision to use 300 µg/g was a deliberately conservative one, to reduce the number of over-treated patients to a minimum. In a recently published study, a calprotectin value >300 µg/g was the best predictor of a flare-up in patients with UC treated with infliximab.29

To use a fixed cut-off level may not be the optimal way to treat patients in a state of subclinical inflammation. We noticed, although not systematically studied, that many patients in remission had an individual stable level of FC over time and were at risk for a flare-up as that calprotectin value changed. Hence, to establish the individual level of FC in remission and use this as a personal level to guide treatment could become a preferable strategy.

In a recent meta-analysis, the pooled sensitivity and specificity for FC to predict a relapse in UC were 0.77 and 0.71, respectively.16 In studies reporting results for patients with UC separately, the positive and the negative predictive values are 49–81% and 79–90%, respectively.23,25,30 In these studies, the best cut-off values for calprotectin to predict a relapse are 120–150 µg/g. Our results are similar, because 57% of patients in the control group with a calprotectin value >300 µg/g did experience a symptomatic relapse.

Therapy in patients with quiescent disease, but at risk of a relapse, is a thrilling challenge. The pros and cons must be weighed, taking the need for efficacious treatment and the risk of side effects into consideration. To initiate treatment with an immunomodulating drug or anti-TNF agent in a patient with asymptomatic disease, based on a laboratory test result alone, is beyond accepted strategies. However, this might be an option if an endoscopy is performed and active inflammation is confirmed. In this type of situation, the FC is instead used to identify patients for a colonoscopy.

In the present study, a simple non-invasive strategy was preferred, so a dose adjustment of the current medication was chosen. The vast majority of the patients in the study were receiving Asacol®, for which 4.8 g has been shown to be more effective than 2.4 g to achieve treatment success in moderately active UC.2 Furthermore, a dose-response effect of an oral 5-ASA preparation is expected to improve the maintenance treatment.8 In a model, this strategy with inflammation targeted treatment using mesalazine agents has also been shown to be cost-effective.31

For several patients, analysis of one sample monthly was not frequent enough to discover an upcoming flare-up; and in most of these patients, calprotectin levels were low (<100 µg/g) in the previously delivered samples. On the other hand, it would not be feasible to deliver samples and run an ELISA more frequently, in clinical practice. A simple, cheap and rapid point-of-care calprotectin test for the patients to use at home would be an attractive option to monitor the disease. In the future, our patients with UC might self-monitor calprotectin levels and adjust therapy, just like diabetics monitor glucose levels and adjust insulin doses, to avoid symptoms and complications.

This new approach to therapy could, theoretically, on the one hand improve quality of life, due to a decrease in disease symptoms; or on the other hand, increase anxiety concerning possible forthcoming relapses. However, in this study it was not possible to draw any conclusions from the SHS questionnaire.

There were some limitations of the study. We were not able to identify a sufficient number of eligible patients and include the planned sample size. Our primary outcome variable did not reach statistical significance, possibly due to a Type II error. Furthermore, all relapses were not endoscopically verified. It is well known that abdominal and bowel symptoms are common in patients with UC, even without inflammatory activity;32,33 thus, in the present study the number of relapses is, if anything, overestimated.

To conclude: In patients with UC, FC-guided dosing of the patient’s 5-ASA agent showed significantly lower relapse rates than for patients in the control group. However, the overall relapse rates were not significantly different. Still, these results suggest a possible new treatment strategy: To identify and optimize therapy for patients with UC at impending risk of a flare-up, before symptoms appear. Future trials, with a modified study design, should be undertaken to evaluate this new concept further.

Acknowledgements

For their contribution with patient inclusions, the authors would like to thank Anders Eriksson of Sahlgrenska University Hospital/Östra and Jerker Andersson of Alingsås Hospital. We also want to thank research nurses Åsa Nilsson and Britt Rydström, as well as Maria Sapnara, for their invaluable assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by ‘The Research and Development Council’ of the Swedish county of Södra Älvsborg (grant numbers VGFOUSA-9064 and -50271), the Health and Medical Care Committee of the Regional Executive Board of the Swedish region Västra Götaland (grant numbers VGFOUREG-73271 and -222711), the Swedbank Sjuhärad and the Alice Swenzons Research Foundation of Borås.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dignass A, Lindsay JO, Sturm A, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis Part 2: Current management. J Crohns Colitis 2012; 6: 991–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Kornbluth A, et al. Delayed-release oral mesalamine at 4.8 g/day (800 mg tablet) for the treatment of moderately active ulcerative colitis: The ASCEND II trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100: 2478–2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis: A randomized study. New Engl J Med 1987; 317: 1625–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levine DS, Riff DS, Pruitt R, et al. A randomized, double-blind, dose-response comparison of balsalazide (6.75 g), balsalazide (2.25 g), and mesalamine (2.4 g) in the treatment of active, mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 1398–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feagan BG, Macdonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012; 10 www.thecochranelibrary.com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kruis W, Schreiber S, Theuer D, et al. Low dose balsalazide (1.5 g twice daily) and mesalazine (0.5 g, three times daily) maintained remission of ulcerative colitis, but high-dose balsalazide (3.0 g twice daily) was superior in preventing relapses. Gut 2001; 49: 783–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fockens P, Mulder CJJ, Tytgat GNJ, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of 1.5 g compared with 3.0 g oral slow-release mesalazine (Pentasa) in the maintenance treatment of ulcerative colitis. Europ J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7: 1025–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feagan BG, Macdonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012; 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henriksen M, Jahnsen J, Lygren I, et al. Ulcerative colitis and clinical course: Results of a 5-year population-based follow-up study (The IBSEN Study). Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006; 12: 543–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Höie O, Wolters F, Riis L, et al. Ulcerative colitis: Patient characteristics may predict 10-yr disease recurrence in a European-wide population-based cohort. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102: 1692–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Røseth AG, Fagerhol MK, Aadland E, et al. Assessment of the neutrophil-dominating protein calprotectin in feces. A methodologic study. Scand J Gastroenterol 1992; 27: 793–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tibble JA, Sigthorsson G, Foster R, et al. Use of surrogate markers of inflammation and Rome criteria to distinguish organic from nonorganic intestinal disease. Gastroenterology 2002; 123: 450–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sipponen T, Savilahti E, Kolho KL, et al. Crohn's disease activity assessed by fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin: Correlation with Crohn's disease activity index and endoscopic findings. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008; 14: 40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoepfer AM, Beglinger C, Straumann A, et al. Ulcerative colitis: Correlation of the Rachmilewitz endoscopic activity index with fecal calprotectin, clinical activity, C-reactive protein and blood leukocytes. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009; 15: 1851–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tibble JA, Sigthorsson G, Bridger S, et al. Surrogate markers of intestinal inflammation are predictive of relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2000; 119: 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mao R, Xiao YL, Gao X, et al. Fecal calprotectin in predicting relapse of inflammatory bowel diseases: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012; 18: 1894–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto T, Shiraki M, Bamba T, et al. Fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin as predictors of relapse in patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis during maintenance therapy. Int J Colorectal Dis 2013; 29: 485–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Røseth AG, Aadland E, Grzyb K. Normalization of faecal calprotectin: A predictor of mucosal healing in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 2004; 39: 1017–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagner M, Peterson CGB, Ridefelt P, et al. Fecal markers of inflammation used as surrogate markers for treatment outcome in relapsing inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14: 5584–5589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Ferrante M, Magro F, et al. Results from the 2nd Scientific Workshop of the ECCO (I): Impact of mucosal healing on the course of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2011; 5: 477–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hjortswang H, Järnerot G, Curman B, et al. The Short Health Scale: A valid measure of subjective health in ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 2006; 41: 1196–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandborn WJ, Regula J, Feagan BG, et al. Delayed-release oral mesalamine 4.8 g/day (800-mg tablet) is effective for patients with moderately active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2009; 137: 1934–1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costa F, Mumolo MG, Ceccarelli L, et al. Calprotectin is a stronger predictive marker of relapse in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn's disease. Gut 2005; 54: 364–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osterman MT, Aberra FN, Cross R, et al. Mesalamine dose escalation reduces fecal calprotectin in patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12: 1887–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D'Incà R, Dal Pont E, Di Leo V, et al. Can calprotectin predict relapse risk in inflammatory bowel disease? Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103: 2007–2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diamanti A, Colistro F, Basso MS, et al. Clinical role of calprotectin assay in determining histological relapses in children affected by inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008; 14: 1229–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walkiewicz D, Werlin SL, Fish D, et al. Fecal calprotectin is useful in predicting disease relapse in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008; 14: 669–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maiden L, Takeuchi K, Baur R, et al. Selective white cell apheresis reduces relapse rates in patients with IBD at significant risk of clinical relapse. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008; 14: 1413–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Vos M, Louis EJ, Jahnsen J, et al. Consecutive fecal calprotectin measurements to predict relapse in patients with ulcerative colitis receiving infliximab maintenance therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013; 19: 2111–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia-Sanchez V, Iglesias-Flores E, Gonzalez R, et al. Does fecal calprotectin predict relapse in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis? J Crohns Colitis 2010; 4: 144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saini SD, Waljee AK, Higgins PDR. Cost utility of inflammation-targeted therapy for patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 10: 1143–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simrén M, Axelsson J, Gillberg R, et al. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease in remission: The impact of IBS-like symptoms and associated psychological factors. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jonefjäll B, Strid H, Öhman L, et al. Characterization of IBS-like symptoms in patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical remission. Neurogastroenterol Motility 2013; 25: e756–e758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]