Abstract

The majority of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) present with advanced-stage disease. Current standard of care is surgery followed by adjuvant radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy or chemoradiation alone. The addition of cetuximab for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or recurrent/metastatic HNSCC has improved overall survival and locoregional control; however, responses are often modest, and treatment resistance is common. A variety of therapeutic strategies are being explored to overcome cetuximab resistance by blocking candidate proteins implicated in resistance mechanisms such as HER2. Several HER2 inhibitors are in clinical development for HNSCC, and HER2-targeted therapy has been approved for several cancers. This review focuses on the biology of HER2, its role in cancer development, and the rationale for clinical investigation of HER2 targeting in HNSCC.

Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the seventh most common cancer worldwide by incidence, with an estimated 600,000 new cases reported each year worldwide, two-thirds of which occur in industrialized nations (1). The five-year survival rate of patients with HNSCC is approximately 40-60% (2), with a high rate of tumor recurrence likely due to the advanced stage (stage III and IV) at diagnosis in many cases. Locoregional disease recurrence is common, and distant metastatic disease arises in 20-30% of patients (3).

The standard of care for advanced HNSCC is surgical resection followed by adjuvant radiation therapy (RT) or chemoradiation (CRT) as a primary treatment approach. However, treatment strategies that target the biological mechanisms of HNSCC tumorigenesis have been, and continue to be, investigated. Currently, cetuximab (Erbitux®), a monoclonal antibody (mAb) to EGFR, is the only FDA-approved molecular targeting agent for the treatment of primary or recurrent/metastatic (R/M) HNSCC. Overexpression of EGFR has been found in approximately 90% of cases of HNSCC and is a predictor of poor prognosis (4-6). However, responses to cetuximab as a single agent do not exceed 13% for patients with recurrent/metastatic disease, are typically short lived, and are not correlated with EGFR expression levels in the primary tumor (7). Many studies have proposed several mechanisms for resistance, the most common of which involves overactivation of other ErbB family receptors, including HER2 (8).

HER2, commonly referred to as ErbB2, c-erbB2, or HER2/neu, is a 185-kDa receptor tyrosine kinase and a member of the ErbB family of proteins (9). The ErbB family consists of 4 closely related receptors: EGFR (ErbB1/HER1), ErbB2 (HER2/neu), ErbB3 (HER3), and ErbB4 (HER4) (10). There is some homology among the family members; each is a membrane-spanning tyrosine kinase that exists as an inactive monomer. Upon ligand binding, the receptors homodimerize or heterodimerize with other members of the ErbB protein family, which triggers autophosphorylation of their intracellular tyrosine kinase domains and initiates a signaling cascade (11). The ErbB proteins are expressed in most epithelial cell layers and play a key role in cell differentiation during development (12).

ErbB2 was originally identified as the oncogene neu in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (NIH3T3 cells) (13). HER2 has since been found to be amplified and overexpressed in a number of human cancers (12), contributing to tumor development, cell cycle progression, and cellular motility and growth. Consequently, HER2 is an active focus of drug development and cancer research. To date, 20 manuscripts have been reported in the peer-reviewed literature assessing HER2 expression in HNSCC tumors (14-33). Six papers have evaluated HER2 targeting in HNSCC preclinical models, and 2 trials have been completed and reported using HER2 inhibitors for this malignancy (18, 34-40). In this review, we will evaluate the preclinical and clinical data implicating HER2 as a therapeutic target in HNSCC.

HER2 in Cancer

HER2 signaling pathway

Unlike the other family members, HER2 lacks a ligand-binding domain, characterizing it as an orphan receptor. The absence of a ligand likely contributes to its role as a powerful signal amplifier for the other ErbB family receptors (41). Evidence suggests that HER2 is the preferred dimerization partner among all members of the protein family, perhaps due to frequent recycling of the HER2 receptor heterodimers to the cell surface as well as the ability of HER2 to decrease the rate of ligand dissociation (42-44).

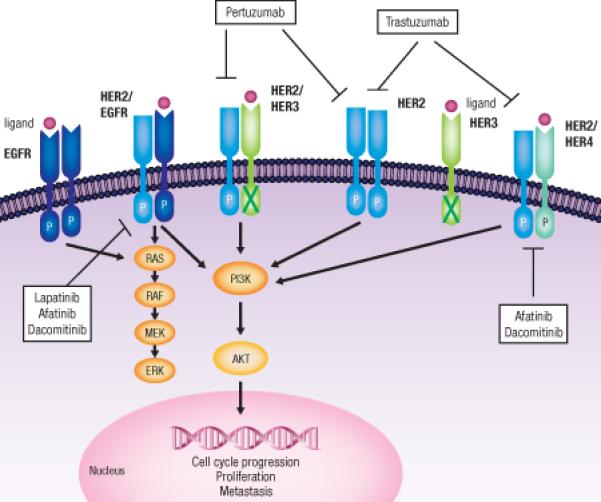

The downstream signaling effects of the HER2 receptor are complex due to the differential effects of the various HER2-containing heterodimers. For example, EGFR/HER2 heterodimers preferentially stimulate the MAPK pathway, while the HER2/HER3 heterodimers activate both the MAPK and the PI3K/v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog (AKT) pathway (45) (Fig. 1). There are at least 10 known EGF-related peptides with varying degrees of affinity for the different heterodimers (11). These peptides do not directly bind to HER2 but instead promote the receptor's heterodimerization and cross-phosphorylation (11). EGFR/HER2 heterodimers are most commonly formed in response to stimulation with EGF, while formation of HER2/HER3 is driven by neuregulins (44). Even when overexpressed, HER2 maintains its dependence on other members of the HER family, namely HER3, for HER2-mediated tumorigenesis (46).

Figure 1. HER2 Signaling.

Human epidermal growth factor receptors, EGFR (HER1), HER2, HER3, and HER4, are receptor tyrosine kinases that play a role in cell growth, survival, and differentiation. Each receptor is composed of an extracellular ligand-binding domain, transmembrane domain, and tyrosine kinase domain. Upon ligand binding, the receptors are activated by auto and cross-phosphorylation. There are no known ligands for HER2, which does not need to be bound to a ligand in order to be activated. HER2 is the preferential dimerization partner among all family members. Dimerization and subsequent phosphorylation lead to activation of downstream targets, including the PI3K/AKT and RAF/MEK/MAPK pathways. Activation of these pathways enhances survival, proliferation, and cell cycle progression. RAS, rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; RAF, v-raf-1 murine leukemia viral oncogene homolog;-AKT, v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1; P, phosphorylation.

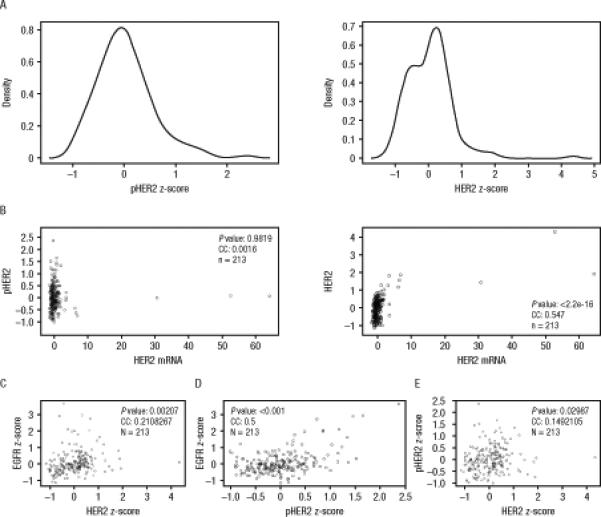

Variations in detection techniques and interpretation methods of HER2 overexpression have contributed to inconsistent reporting of overexpression of HER2 in many types of cancer, including HNSCC. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) publishes guidelines for assessing HER2 status in breast carcinomas via IHC and FISH (47). While distinct HER2 testing protocols have also been established in gastric cancer, none exist for HNSCC (48). Consequently, pathologists apply the IHC/FISH scoring techniques for breast cancers to HNSCC, a biologically different carcinoma. Reports of HER2 overexpression range from 0-47% in HNSCC (15, 20, 25). In laryngeal cancer, positive HER2 staining has been reported in 68% of cases (24). Azemar et al found significantly elevated levels of HER2 in 26 out of 45 primary HNSCC samples (49). We assessed 426 HNSCC tumors in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database and found 18 cases (4%) with mRNA upregulation; however, only 8 of those 18 also harbored HER2 gene amplification. In a separate analysis of 213 HNSCC tumors in The Cancer Proteome Atlas (TCPA), low levels of activated (phosphorylated HER2) or total HER2 expression were detected (Fig. 2A). Although HER2 mRNA levels correlated with HER2 protein expression, no correlation was observed with levels of phosphorylated HER2 (Fig. 2B). The protein levels of TCGA tumors were determined by reverse phase protein array (RPPA), a high throughput technique that reports HER2 scoring intensity on a continuum. Assadi et al. compared RPPA results to IHC and found a correlation of 0.86 (50). Comparing protein detection techniques to those for DNA or RNA is not as simple. Levels of RNA in TCGA tumors were determined by RNAseq processing, a profiling method that is subject to sample bias. Moreover, there remains a gap between mRNA and protein levels because of various degrees of regulation.

Figure 2.

Landscape of HER2 expression in HNSCC tumors (TCGA database, provisional). (A) pHER2 and HER2 expression z-scores were obtained from the TCPA database (The Cancer Proteome Atlas) for HNSCC tumors (n=213). pHER2 expression levels were plotted as a function of frequency in R version 3.0.2. (B) pHER2 levels do not correlate with HER2 mRNA expression. HER2 levels do correlate with HER2 mRNA expression. Reverse phase protein array (RPPA) data were obtained from the TCPA database for HNSCC tumors. Protein levels and mRNA expression were compared using a Pearson's correlation in R version 3.0.2. (C and D) RPPA (reverse phase protein array) expression for (C) HER2 and (D) pHER2 correlates with RPPA expression for EGFR. (E) RPPA expression for pHER2 correlates with RPPA expression for HER2. RPPA data for pHER2, HER2, and EGFR was obtained from the TCPA database for HNSCC tumors. Protein levels were compared using a Pearson's correlation in R version 3.0.2.

Elevated HER2 overexpression has been reportedly associated with worse prognosis, increased recurrence, and decreased overall survival (OS) in HNSCC (26, 51). Cavalot and colleagues found that frequency of HER2 overexpression was significantly higher in patients with more aggressive disease occurring in conjunction with metastatic lymph nodes (15). Additionally, the 5-year OS and the 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) probability were significantly lower for HER2-positive patients compared with HER2-negative individuals (15). Wei et al found that in two laryngeal tumors, HER2 staining was higher in the metastases (2+ and 3+), while staining was lower in the corresponding primary tumors (17). However, other studies have shown that HER2 is not an independent prognostic factor (22, 29). Our analysis found that among the 213 tumors in the TCGA cohort, neither mRNA upregulation of HER2 nor increased expression of total or phosphorylated HER2 protein was an independent predictor of OS (data not shown). However, the small sample size limits the conclusiveness of this analysis.

HER2 has been found to be co-expressed with EGFR in HNSCC tumors (33). Among the 213 HNSCC tumors in the TCPA, expression of both HER2 and activated HER2 (pHER2) correlated with EGFR expression (Fig. 2C and D). As expected, expression of pHER2 correlated with total HER2 expression (Fig. 2E). These findings suggest that HER2 co-expression may contribute to the negative prognostic impact of EGFR because co-expression/activation has been reported to be associated with resistance to therapeutic agents (35, 52). Wheeler et al generated cetuximab-resistant NSCLC and HNSCC cell lines and found that the cetuximab-resistant cell lines expressed higher levels of phosphorylated receptor tyrosine kinases, including HER2, than the parental cell lines (52). Additionally, among all of the cetuximab-resistant cell lines, EGFR had increased co-immunoprecipitation with HER2 and HER3 when compared to the parental cell lines. Treating these cells with increasing concentrations of cetuximab had no effect on the autophosphorylation of EGFR or the activity of HER2. However, this resistance was overcome with several TKIs, including erlotinib, gefitinib, and the pan-HER irreversible inhibitor canertinib (CI-1033). We previously reported that treatment with a dual EGFR-HER2 kinase inhibitor overcame acquired resistance of HNSCC tumors to cetuximab in xenograft tumor models (35). Together, these findings validate the active investigation of HER2 as molecular target for HNSCC therapy rationale for HER2 as a molecular target for HNSCC therapies.

HER2 Inhibitors

Monoclonal antibodies: preclinical and clinical studies

There are a number of strategies used to inhibit HER2, including mAbs. Trastuzumab is a humanized mAb that binds domain IV of the extracellular domain of the HER2 receptor, preventing activation of its intracellular tyrosine kinase (53, 54). Trastuzumab has several possible mechanisms of action, including prevention of HER2 receptor dimerization, increased endocytosis of the receptor, and inhibition of the generation of a constitutively active truncated intracellular HER2 molecule (53, 55). A phase II trial evaluated trastuzumab in combination with paclitaxel (Taxol®) and cisplatin (56). The addition of trastuzumab did not significantly improve patient response rate to the chemotherapy treatments.

Pertuzumab is a humanized mAb to the HER2 receptor that binds domain II of the extracellular domain and inhibits heterodimerization of HER2 with other members of the HER family (57). Because blocking the formation of heterodimers, particularly HER2/HER3, has had promising effects in the treatment of breast cancer (58, 59), pertuzumab was studied in combination with gefitinib, an EGFR inhibitor, in HNSCC cell lines (60). The cell lines that harbored high levels of phosphorylated HER2 and HER3 were more resistant to gefitinib, and a similar trend was observed for cell lines with amplified EGFR. However, combination treatments of gefitinib and pertuzumab overcame resistance (60). Currently, there are no reports of pertuzumab in HNSCC preclinical models or patients.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors: preclinical studies

Small molecule TKIs that bind to the ATP binding site of the HER molecule are also effective therapeutic agents. Lapatinib, a reversible dual TKI of both EGFR and HER2, is FDA approved for the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer (61). By preventing phosphorylation and subsequent activation of the PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK pathways, lapatinib results in an increase in apoptosis and decrease in cellular proliferation and growth. Just like other small molecule TKIs, lapatinib is administered orally and well tolerated by patients (61). An ex vivo study evaluating the combined effect of lapatinib and cisplatin in 72 different patient-derived HNSCC samples found that lapatinib provided an additive effect by limiting colony formation (38). However, there were significant differences in the response of individual tumors to lapatinib treatment, evident by the wide range of IC50 concentrations (38). Another study evaluating the combined effect of lapatinib with either cisplatin or paclitaxel found additive effects both in vivo and in vitro (40). Lapatinib reduced proliferation of HNSCC cells, but no correlation was found between expression levels of EGFR or HER2 and the anti-proliferative effects (40). In vivo xenograft studies in mice bearing YCU-H891 HNSCC cells demonstrated that lapatinib alone induced apoptosis and displayed antitumor activity (40). Although lapatinib alone did not inhibit angiogenesis, inhibition of angiogenesis was observed when lapatinib was combined with paclitaxel. Additionally, the combination of cisplatin or paclitaxel with lapatinib resulted in enhanced antitumor activity primarily by increasing apoptosis (40).

The irreversible ErbB family blocker afatinib (Gilotrif®) binds to the tyrosine kinase domains of EGFR, HER2, and HER4 (62). The FDA recently approved afatinib for the treatment of patients with NSCLC harboring EGFR mutations. Owing to its irreversible activity and multireceptor binding, afatinib is also being investigated for treatment of patients with other ErbB-driven cancers, including HNSCC (63). To date, a few studies report on the use of afatinib in preclinical HNSCC models. In one study, mice inoculated with FaDu cells, which are cells derived from a hypopharyngeal cancer, received varying doses of afatinib; at every dose, afatinib significantly decreased tumor volume size when compared with the control (63).

Dacomitinib, another irreversible pan-HER kinase inhibitor is an experimental drug under investigation in NSCLC, gastric, glioma, and HNSCC. It has shown pre-clinical efficacy alone and in combination with ionizing radiation in HNSCC cell lines and mice models (64). HNSCC cell lines, UT-SCC-8 and UT-SCC-42a, showed sensitivity to dacomitinib, with IC50s of 25nM, with combination treatment of dacomitinib and IR further reducing cell viability. While dacomitinib was effective in inhibiting EGFR phosphorylation, reduction of HER2 phosphorluation was not evaluated (64).

Clinical trials of HER2 TKIs in HNSCC

Ongoing trials of anti-HER agents in clinical development in HNSCC are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2. IC50 values for these agents are listed in Table 3. Due to the current palliative nature of treatment associated with recurrent and/or metastatic HNSCC, Table 1 and Table 2 delineate the trials as either curative or palliative, curative meaning therapy for non-recurrent/nonmetastatic HNSCC.

Table 1.

Trials of anti-HER family agents for non-recurrent/non-metastatic HNSCC (curative therapy)

| Clinical trial | Phase | Study regimens | Estimated accrual; study population | Primary endpoint | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT01783587 | I | Afatinib plus CRT or afatinib plus RT | N=38; intermediate-and high-risk HNSCC | DLT | Recruiting |

| NCT01737008 | I | Dacomitinib plus CRT or RT | N=34; LA HNSCC | MTD | Recruiting |

| NCT01732640 | I/II | Afatinib plus carboplatin and paclitaxel | N=71; primary unresected patients with LA, HPV-negative, stage III or IV a/b HNSCC | MTD, objective tumor response | Recruiting |

| NCT01824823 | II | Afatinib or placebo | N=108; patients with LA, stage III or IV HNSCC | DFS | Recruiting |

| NCT01538381 | II | Afatinib or observation | N=30; newly diagnosed HNSCC | Reduction of tumor | Recruiting |

| NCT01415674 | II | Afatinib | N=60; untreated nonmetastatic HNSCC | Potential predictive biomarkers of afatinib activity | Recruiting |

| NCT00490061 | II | Lapatinib plus RT | N=60; stage III/IV HNSCC who cannot tolerate concurrent CRT | TTP | Active, not recruiting |

| NCT00387127 | II | Lapatinib plus CRT or placebo plus CRT | N=67; stage III, IV a/b HNSCC | Complete response rate | Active, not recruiting |

| NCT01427478 | III | Afatinib or placebo | N=315; resected, CRT-treated HNSCC with macroscopically complete resection of disease | DFS | Recruiting |

| NCT02131155 (LUX-Head & Neck 4) | III | Afatinib or placebo | N=150; primary unresected, stage III, IV a/b LA HNSCC without evidence of disease post CRT | DFS | Recruiting |

| NCT01345669 (LUX-Head & Neck 2) | III | Afatinib or placebo | N=669; primary unresected, stage III, IV a/b LA HNSCC without evidence of disease post CRT | DFS | Recruiting |

Descriptions for ongoing (recruiting; active, not recruiting; or not yet recruiting) phase I/II clinical trials of anti-HER2 family agents for HNSCC as of September 2014 (as per listings on ClinicalTrials.gov).

Abbreviations: HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell cancer; LA, locally advanced; HPV; human papillomavirus; MTD, maximum tolerated dose; DFS, disease-free survival; CRT, chemoradiation therapy; RT, radiotherapy; DLT, dose limiting toxicity; TTP, time to progression.

Table 2.

Trials of Anti-HER Family Agents for recurrent/metastatic HNSCC (palliative therapy)

| Clinical trial | Phase | Study regimens | Estimated accrual; study population | Primary endpoint | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT01345682 (LUX-Head & Neck 1) | III | Afatinib or methotrexate | N=474; R/M HNSCC with progression after at least 2 cycles platinum-based therapy | PFS | Active, not recruiting |

| NCT01856478 (LUX-Head & Neck 3) | III | Afatinib or methotrexate | N=300; R/M HNSCC with progression after a cisplatin and/or carboplatin therapy | PFS | Recruiting |

Description of ongoing clinical trials of anti-HER2 family agents for recurrent/metastatic HNSCC as of September 2014 (as per listings on ClinicalTrials.gov).

Abbreviations: HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell cancer; R/M, recurrent/metastatic; PFS, progression-free survival.

Table 3.

IC50 values of anti-HER family agents in HNSCC

| Agents | EGFR | HER2 |

|---|---|---|

| Lapatinb | 10.8 | 9.2 |

| Afatinib | 0.5 | 14 |

| Dacomitinib | 6 | 45.7 |

The IC50 values for anti-HER family agents. Values are expressed in nanomolar.

Non-recurrent/non-metastatic HNSCC

Completed clinical trials for patients with non-recurrent/non-metastatic HNSCC include investigations of lapatinib therapy. In a randomized phase II placebo-controlled trial patients with previously untreated locally advanced (LA) HNSCC received either lapatinib or placebo for 2 to 6 weeks, followed by CRT (34). The response rate before CRT was 17% (n=4, 7% with HER2 overexpression and amplification in 4%) among 24 patients receiving lapatinib and 0% among all 16 patients receiving the placebo. Despite a clinical response, the patients who received lapatinib monotherapy did not have a significant increase in apoptosis compared with those who received placebo. All of the lapatinib responders had EGFR overexpression, and 50% had HER2 expression. Although no other biological characteristics predicted response to lapatinib therapy, the small sample size warrants future investigation (34).

Another phase II trial did not show the same success of lapatinib as a monotherapy (36). Patients were separated based on their treatment history with an EGFR inhibitor. Patients with no prior treatment with an EGFR inhibitor (EGFR-naive) had a 6-month progression-free survival (PFS) rate of 7%, and the median PFS was 52 days. The EGFR-naive group's median OS and 6-month OS rate were 288 days and 52%, respectively. At the time of analysis, all patients in this group progressed. Similarly, all patients in the previously EGFR inhibitor–treated group had died. The 6-month median PFS was 52 days, and the PFS rate was 6%. The median OS was 155 days, and the 6-month OS rate was 39%. Most HNSCC tumors expressed both EGFR and HER2, and post-treatment biopsies showed a significant decrease in pHER2 levels. Samples were analyzed for the presence of HER2-activating mutations, but only one was found to contain a mutation, which did not produce a phenotype. Although lapatinib was well tolerated by all patients, it appeared to be largely inactive as a monotherapy in both EGFR-naive and EGFR-refractory patients. A phase III (NCT00424255) trial did not show improvement when lapatinib was added to radiation or cisplatin therapy in the post-operative setting in HNSCC patients at high risk for recurrence. Patients with resected stage II to stage IVA HNSCC were randomized to receive chemotherapy/radiation therapy with either placebo or lapatinib prior to, during, and following CT-RT. There was no significant difference in DFS between treatment arms.

While lapatinib has not demonstrated clear efficacy in HNSCC, it still remains in active clinical development for patients with non-recurrent/non-metastatic HNSCC. Two actively accruing trials are designed to evaluate lapatinib plus RT or CRT (Table 1). In a recently completed phase III trial, examining lapatinib with concurrent CRT followed by maintenance monotherapy for high-risk patients with resected HNSCC (NCT00424255), addition of lapatinib to CRT failed to prolong DFS (65). HER2 mutations are rare in HNSCC (2% of TCGA) and have not been evaluated as a predictive biomarker to select HNSCC patients likely to benefit from anti-HER2 therapy. Attempts to correlate levels of EGFR, phosphorylated EGFR (pEGFR) and HER2 with clinical benefit from lapatinib as a monotherapeutic agent have not been informative to date.

While there are no completed clinical trials, afatinib and dacomitinib are undergoing active investigation for therapy in non-recurrent/non-metastatic HNSCC. Table 1 describes the several ongoing trials investigating these agents alone or in combination with RT or CRT.

Recurrent/metastatic HNSCC

Among completed clinical trials, afatinib was compared with cetuximab in a recently published phase II study of patients with R/M HNSCC (NCT00514943) (66). The disease control rate by investigator review was 50% for the afatinib-receiving cohort and 56.5% for the cetuximab-receiving cohort (P = 0.48), with similar rates observed by independent central review. Centrally reviewed median PFS was 13.0 weeks for afatinib and 15.0 weeks for the cetuximab group (P = 0.71). Preliminary report of another completed phase III trial (NCT01345682 LUX-Head & Neck 1) suggested that afatinib improved PFS as well as patient-reported outcomes. Patients with R/M HNSCC who progressed on or after platinum-based therapy were randomized to receive afatinib or methotrexate (MTX). Afatinib significantly improved PFS (median 2.6 months), disease control rate (49.1%), and objective response rate (10.2%) compared to MTX (median 1.7 months, 38.5%, 5.6%). Afatinib did not significantly improve OS (median 6.8 months) compared to MTX (median 6.2 months).

Table 2 describes the phase III trials in which afatinib is being compared to methotrexate for patients with R/M HNSCC (NCT01345682/LUX-Head & Neck 1; NCT01856478/LUX-Head & Neck 3) (Table 2).

Conclusion

The presence of activating HER2 mutations or HER2 overexpression, primarily due to gene amplification, has been associated with reproducible and robust responses to HER2-targeting therapy in most malignancies including breast, lung, and gastric cancer. HER2 mutations and HER2 gene amplifications are rare in HNSCC. EGFR is a validated prognostic and therapeutic target for treatment of HNSCC, and the mAb cetuximab is the only FDA-approved molecular targeting agent in HNSCC. EGFR is frequently overexpressed in HNSCC tumors, resulting in constitutive downstream signaling activity. EGFR can heterodimerize with HER2, and preclinical evidence suggests that co-targeting of EGFR and HER2 may augment cetuximab responses and mitigate therapeutic resistance. The majority of agents under active clinical investigation in HNSCC dually target EGFR and HER2. Because a specific molecular inhibitor strategy is unlikely to be effective in all cases, the identification of biomarkers that will predict clinical responses to ErbB family blockers in HNSCC is of paramount importance.

Acknowledgments

Editorial and formatting assistance was provided by Melissa Brunckhorst, PhD, of MedErgy, which was contracted and funded by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (BIPI). BIPI was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as well as intellectual property considerations.

Grant Support

J.R. Grandis was supported by the NIH under award numbers R01CA77308 and P50CA097190 and the American Cancer Society.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN 2008: cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10 [monograph on the Internet] International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon, France: 2010. [2014 Sep 3]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vermorken JB, Specenier P. Optimal treatment for recurrent/metastatic head and neck cancer. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 7):vii, 252–61. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grandis JR, Tweardy DJ. Elevated levels of transforming growth factor alpha and epidermal growth factor receptor messenger RNA are early markers of carcinogenesis in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3579–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ang KK, Berkey BA, Tu X, Zhang HZ, Katz R, Hammond EH, et al. Impact of epidermal growth factor receptor expression on survival and pattern of relapse in patients with advanced head and neck carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7350–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubin Grandis J, Melhem MF, Gooding WE, Day R, Holst VA, Wagener MM, et al. Levels of TGF-alpha and EGFR protein in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and patient survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:824–32. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.11.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vermorken JB, Trigo J, Hitt R, Koralewski P, az-Rubio E, Rolland F, et al. Open-label, uncontrolled, multicenter phase II study to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of cetuximab as a single agent in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck who failed to respond to platinum-based therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2171–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yonesaka K, Zejnullahu K, Okamoto I, Satoh T, Cappuzzo F, Souglakos J, et al. Activation of ERBB2 signaling causes resistance to the EGFR-directed therapeutic antibody cetuximab. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:99ra86. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coussens L, Yang-Feng TL, Liao YC, Chen E, Gray A, McGrath J, et al. Tyrosine kinase receptor with extensive homology to EGF receptor shares chromosomal location with neu oncogene. Science. 1985;230:1132–9. doi: 10.1126/science.2999974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson NG, Ahmad T. ErbB receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors as therapeutic agents. Front Biosci. 2002;7:d1926–d1940. doi: 10.2741/A889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roskoski R., Jr The ErbB/HER receptor protein-tyrosine kinases and cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;319:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:127–37. doi: 10.1038/35052073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shih C, Padhy LC, Murray M, Weinberg RA. Transforming genes of carcinomas and neuroblastomas introduced into mouse fibroblasts. Nature. 1981;290:261–4. doi: 10.1038/290261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xia W, Lau YK, Zhang HZ, Xiao FY, Johnston DA, Liu AR, et al. Combination of EGFR, HER-2/neu, and HER-3 is a stronger predictor for the outcome of oral squamous cell carcinoma than any individual family members. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:4164–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cavalot A, Martone T, Roggero N, Brondino G, Pagano M, Cortesina G. Prognostic impact of HER-2/neu expression on squamous head and neck carcinomas. Head Neck. 2007;29:655–64. doi: 10.1002/hed.20574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheikh Ali MA, Gunduz M, Nagatsuka H, Gunduz E, Cengiz B, Fukushima K, et al. Expression and mutation analysis of epidermal growth factor receptor in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:1589–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00861.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei Q, Sheng L, Shui Y, Hu Q, Nordgren H, Carlsson J. EGFR, HER2, and HER3 expression in laryngeal primary tumors and corresponding metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1193–201. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9771-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang M, Taylor CE, Piao L, Datta J, Bruno PA, Bhave S, et al. Genetic and chemical targeting of epithelial-restricted with serine box reduces EGF receptor and potentiates the efficacy of afatinib. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:1515–25. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pardis S, Sardari Y, Ashraf MJ, Andisheh TA, Ebrahimi H, Purshahidi S, et al. Evaluation of tissue expression and salivary levels of HER2/neu in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;24:161–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sardari Y, Pardis S, Tadbir AA, Ashraf MJ, Fattahi MJ, Ebrahimi H, et al. HER2/neu expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients is not significantly elevated. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:2891–6. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.6.2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hama T, Yuza Y, Suda T, Saito Y, Norizoe C, Kato T, et al. Functional mutation analysis of EGFR family genes and corresponding lymph node metastases in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2012;29:19–25. doi: 10.1007/s10585-011-9425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ali MA, Gunduz M, Gunduz E, Tamamura R, Beder LB, Katase N, et al. Expression and mutation analysis of her2 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Invest. 2010;28:495–500. doi: 10.3109/07357900903476778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beckhardt RN, Kiyokawa N, Xi L, Liu TJ, Hung MC, El-Naggar AK, et al. HER-2/neu oncogene characterization in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:1265–70. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1995.01890110041008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khademi B, Shirazi FM, Vasei M, Doroudchi M, Gandomi B, Modjtahedi H, et al. The expression of p53, c-erbB-1 and c-erbB-2 molecules and their correlation with prognostic markers in patients with head and neck tumors. Cancer Lett. 2002;184:223–30. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angiero F, Sordo RD, Dessy E, Rossi E, Berenzi A, Stefani M, et al. Comparative analysis of c-erbB-2 (HER-2/neu) in squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue: does over-expression exist? And what is its correlation with traditional diagnostic parameters? J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:145–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia W, Lau YK, Zhang HZ, Liu AR, Li L, Kiyokawa N, et al. Strong correlation between c-erbB-2 overexpression and overall survival of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma BB, Poon TC, To KF, Zee B, Mo FK, Chan CM, et al. Prognostic significance of tumor angiogenesis, Ki 67, p53 oncoprotein, epidermal growth factor receptor and HER2 receptor protein expression in undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma--a prospective study. Head Neck. 2003;25:864–72. doi: 10.1002/hed.10307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shiga H, Rasmussen AA, Johnston PG, Langmacher M, Baylor A, Lee M, et al. Prognostic value of c-erbB2 and other markers in patients treated with chemotherapy for recurrent head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2000;22:599–608. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200009)22:6<599::aid-hed9>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freier K, Joos S, Flechtenmacher C, Devens F, Benner A, Bosch FX, et al. Tissue microarray analysis reveals site-specific prevalence of oncogene amplifications in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1179–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koynova DK, Tsenova VS, Jankova RS, Gurov PB, Toncheva DI. Tissue microarray analysis of EGFR and HER2 oncogene copy number alterations in squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2005;131:199–203. doi: 10.1007/s00432-004-0627-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tse GM, Yu KH, Chan AW, King AD, Chen GG, Wong KT, et al. HER2 expression predicts improved survival in patients with cervical node-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141:467–73. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.06.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khan AJ, King BL, Smith BD, Smith GL, Digiovanna MP, Carter D, et al. Characterization of the HER-2/neu oncogene by immunohistochemical and fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis in oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:540–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ibrahim SO, Lillehaug JR, Johannessen AC, Liavaag PG, Nilsen R, Vasstrand EN. Expression of biomarkers (p53, transforming growth factor alpha, epidermal growth factor receptor, c-erbB-2/neu and the proliferative cell nuclear antigen) in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 1999;35:302–13. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(98)00120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Del Campo JM, Hitt R, Sebastian P, Carracedo C, Lokanatha D, Bourhis J, et al. Effects of lapatinib monotherapy: results of a randomised phase II study in therapy-naive patients with locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:618–27. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quesnelle KM, Grandis JR. Dual kinase inhibition of EGFR and HER2 overcomes resistance to cetuximab in a novel in vivo model of acquired cetuximab resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5935–44. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Souza JA, Davis DW, Zhang Y, Khattri A, Seiwert TY, Aktolga S, et al. A phase II study of lapatinib in recurrent/metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2336–43. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uno M, Otsuki T, Kurebayashi J, Sakaguchi H, Isozaki Y, Ueki A, et al. Anti-HER2-antibody enhances irradiation-induced growth inhibition in head and neck carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:474–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schrader C, Boehm A, Reiche A, Diet A, Mozet C, Wichmann G. Combined effects of lapatinib and cisplatin on colony formation of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:3191–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rusnak DW, Alligood KJ, Mullin RJ, Spehar GM, Renas-Elliott C, Martin AM, et al. Assessment of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR, ErbB1) and HER2 (ErbB2) protein expression levels and response to lapatinib (Tykerb, GW572016) in an expanded panel of human normal and tumour cell lines. Cell Prolif. 2007;40:580–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2007.00455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kondo N, Tsukuda M, Ishiguro Y, Kimura M, Fujita K, Sakakibara A, et al. Antitumor effects of lapatinib (GW572016), a dual inhibitor of EGFR and HER-2, in combination with cisplatin or paclitaxel on head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2010;23:957–63. doi: 10.3892/or_00000720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arkhipov A, Shan Y, Kim ET, Dror RO, Shaw DE. Her2 activation mechanism reflects evolutionary preservation of asymmetric ectodomain dimers in the human EGFR family. Elife. 2013;2:e00708. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lenferink AE, Pinkas-Kramarski R, van de Poll ML, van Vugt MJ, Klapper LN, Tzahar E, et al. Differential endocytic routing of homo- and hetero-dimeric ErbB tyrosine kinases confers signaling superiority to receptor heterodimers. EMBO J. 1998;17:3385–97. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lenferink AE, Busse D, Flanagan WM, Yakes FM, Arteaga CL. ErbB2/neu kinase modulates cellular p27(Kip1) and cyclin D1 through multiple signaling pathways. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6583–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tzahar E, Waterman H, Chen X, Levkowitz G, Karunagaran D, Lavi S, et al. A hierarchical network of interreceptor interactions determines signal transduction by Neu differentiation factor/neuregulin and epidermal growth factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5276–87. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holbro T, Civenni G, Hynes NE. The ErbB receptors and their role in cancer progression. Exp Cell Res. 2003;284:99–110. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holbro T, Beerli RR, Maurer F, Koziczak M, Barbas CF, III, Hynes NE. The ErbB2/ErbB3 heterodimer functions as an oncogenic unit: ErbB2 requires ErbB3 to drive breast tumor cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8933–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1537685100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolff A, Hammond E, Hicks D, Dowsett M, McShane L, Allison K, et al. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3997–4013. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.9984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruschoff J, Hanna W, Bilous M, Hofmann M, Osamura R, Penault-Llorca F, et al. HER2 testing in gastric cancer: a practical approach. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:637–50. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Azemar M, Schmidt M, Arlt F, Kennel P, Brandt B, Papadimitriou A, et al. Recombinant antibody toxins specific for ErbB2 and EGF receptor inhibit the in vitro growth of human head and neck cancer cells and cause rapid tumor regression in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2000;86:269–75. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000415)86:2<269::aid-ijc18>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Assadi M, Lamerz J, Jarutat T, Farfsing A, Paul H, Gierke B, et al. Multiple protein analysis of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue samples with reverse phase protein arrays. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:2615–22. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.023051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sato-Kuwabara Y, Neves JI, Fregnani JH, Sallum RA, Soares FA. Evaluation of gene amplification and protein expression of HER-2/neu in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma using Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (FISH) and immunohistochemistry. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wheeler DL, Huang S, Kruser TJ, Nechrebecki MM, Armstrong EA, Benavente S, et al. Mechanisms of acquired resistance to cetuximab: role of HER (ErbB) family members. Oncogene. 2008;27:3944–56. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hudis CA. Trastuzumab--mechanism of action and use in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:39–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumler I, Tuxen MK, Nielsen DL. A systematic review of dual targeting in HER2-positive breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:259–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tse C, Gauchez AS, Jacot W, Lamy PJ. HER2 shedding and serum HER2 extracellular domain: Biology and clinical utility in breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;38:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gillison ML, Glisson BS, O'Leary E, Murphy BA, Levine MA, Kies MS, et al. Phase II trial of trastuzumab (T), paclitaxel (P) and cisplatin (C) in metastatic (M) or recurrent (R) head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC): Response by tumor EGFR and HER2/neu status. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(suppl):18s. abstr 5511. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Metzger-Filho O, Winer EP, Krop I. Pertuzumab: optimizing HER2 blockade. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5552–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baselga J, Gelmon KA, Verma S, Wardley A, Conte P, Miles D, et al. Phase II trial of pertuzumab and trastuzumab in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer that progressed during prior trastuzumab therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1138–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee-Hoeflich ST, Crocker L, Yao E, Pham T, Munroe X, Hoeflich KP, et al. A central role for HER3 in HER2-amplified breast cancer: implications for targeted therapy. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5878–87. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Erjala K, Sundvall M, Junttila TT, Zhang N, Savisalo M, Mali P, et al. Signaling via ErbB2 and ErbB3 associates with resistance and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) amplification with sensitivity to EGFR inhibitor gefitinib in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4103–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Medina PJ, Goodin S. Lapatinib: a dual inhibitor of human epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1426–47. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li D, Ambrogio L, Shimamura T, Kubo S, Takahashi M, Chirieac LR, et al. BIBW2992, an irreversible EGFR/HER2 inhibitor highly effective in preclinical lung cancer models. Oncogene. 2008;27:4702–11. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harbeck N, Solca F, Gauler TC. Preclinical and clinical development of afatinib: a focus on breast cancer and squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Future Oncol. 2014;10:21–40. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Williams J, Kim I, Ito E, Shi W, Yue S, Siu L, et al. Pre-clinical characterization of dacomitinib (PF-00299804), an irreversible pan-ErbB inhibitor, combined with ionizing radiation for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e9855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Harrington KJ, Temam S, D'Cruz A, Jain MM, D'Onofrio I, et al. Final analysis: A randomized, blinded, placebo (P)-controlled phase III study of adjuvant postoperative lapatinib (L) with concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy (CH-RT) in high-risk patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN). J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl):5s. abstr 6005. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Seiwert TY, Fayette J, Cupissol D, Del Campo JM, Clement PM, Hitt R, et al. A randomized, phase 2 study of afatinib versus cetuximab in metastatic or recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1813–20. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]