Abstract

HIV treatment requires lifelong adherence to medication regimens that comprise inconvenient scheduling, adverse side effects, and lifestyle changes. Antiretroviral adherence and treatment fatigue have been inextricably linked. Adherence in HIV-infected populations has been well investigated; however, little is known about treatment fatigue. This review examines the current state of the literature on treatment fatigue among HIV populations and provides an overview of its etiology and potential consequences. Standard systematic research methods were used to gather published papers on treatment fatigue and HIV. Five databases were searched using PRISMA criteria. Of 1,557 studies identified, 21 met the following inclusion criteria: (a) study participants were HIV-infected, (b) participants were prescribed antiretroviral medication, (c) the article referenced treatment fatigue, (d) the article was published in a peer-reviewed journal, and (e) text was available in English. Only seven articles operationally defined treatment fatigue, with three themes emerging throughout the definitions: (1) pill burden, (2) loss of desire to adhere to the regimen, and (3) nonadherence to regimens as a consequence of treatment fatigue. Based on these studies, treatment fatigue may be defined as “decreased desire and motivation to maintain vigilance in adhering to a treatment regimen among patients prescribed long-term protocols.” The cause and course of treatment fatigue appear to vary by developmental stage. To date, only structured treatment interruptions have been examined as an intervention to reduce treatment fatigue in children and adults. No behavioral interventions have been developed to reduce treatment fatigue. Further, only qualitative studies have examined treatment fatigue conceptually. Studies designed to systematically assess treatment fatigue are needed. Increased understanding of the course and duration of treatment fatigue is expected to improve adherence interventions, thereby improving clinical outcomes for individuals living with HIV.

Keywords: treatment fatigue, HIV, review, adherence

Introduction

HIV treatment requires strict adherence and lifestyle changes, including integration into daily routine, coping with side effects, consistently obtaining prescription refills and attending medical appointments, and remembering to take medications throughout the patient’s life (Chesney et al., 2000; Friedland, 2006). Treatment fatigue has been identified as a consequence of long-term regimens resulting in a decline in adherence over time and with subsequent regimens (Arem et al., 2011; Ostrop, Hallett, & Gill, 2000; Cook et al., 2011; Gardner, Burman, Maravi, & Davidson, 2006; Ickovics & Meade, 2002; Johnson, Stallworth, & Neilands, 2003; Paterson et al., 2000). Although we have extensive knowledge on mechanisms associated with nonadherence and have developed interventions to promote adherence, little is known about the development and course of treatment fatigue. This systematic literature review aimed to examine treatment fatigue among people living with HIV (PLWH) by (a) identifying factors contributing to the etiology and maintenance of treatment fatigue, (b) examining the extent to which treatment fatigue is systematically measured, and (c) identifying methods of intervention.

Methods

Search strategy and selection of studies

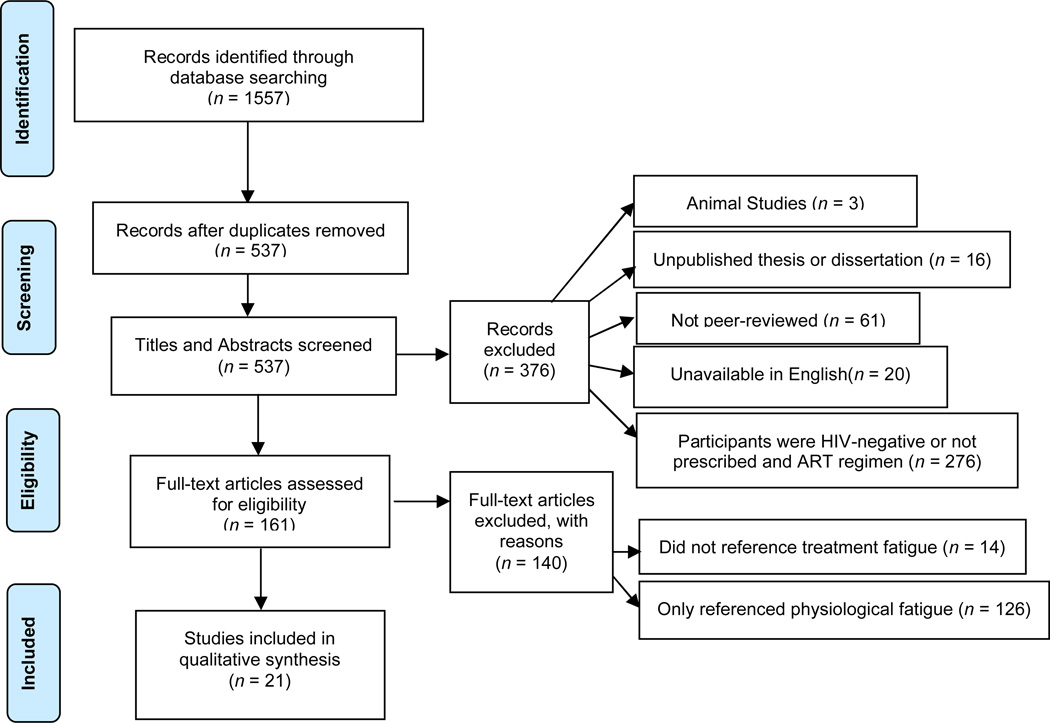

Studies published through August 2013 that examined treatment fatigue among PLWH prescribed ART were reviewed based on PRISMA guidelines. Searches were conducted within PsycINFO, PubMed, CINAHL, Medline, and Web of Science databases using the following terms: ("treatment" OR "pill" OR "medication" OR "regimen") AND “fatigue” AND “HIV.” After deleting duplicate references (n = 1,020), 537 articles were identified. Articles were excluded if the work (a) represented an unpublished thesis or dissertation; (b) was not peer-reviewed; (c) was unavailable in English; (d) study participants were HIV seronegative; (e) study participants were not prescribed ART; (f) the study comprised animal research; (g) made no reference to fatigue or cited only physiological fatigue. Twenty-one studies were included in the final review (see Figure 1). Data extracted included: (a) definition of the construct; (b) developmental factors; (c) potential etiological factors, (d) potential consequences; (e) developmental factors; (g) method of measurement; and (h) interventions.

Figure 1.

Study Flow Diagram

Results

Definition

A variety of terms were used to describe the targeted concept, including “pill fatigue,” “medication fatigue,” “treatment fatigue,” “regimen fatigue,” “dosing fatigue,” “drug fatigue,” and “injection fatigue” (see Table 1). Only seven articles provided a definition (see Table 2), resulting in three primary themes: (1) “pill burden,” (2) “loss of desire” or “tiring” of adhering to treatment, and (3) nonadherence. The most thorough definition was provided by Miramontes (2001), who characterized treatment fatigue by (a) patient characteristics (e.g., life stressors, cultural/health beliefs), (b) patient-provider relationship (e.g., respect, trust, communication), and (c) regimen issues (dosing restrictions, impact on lifestyle).

Table 1.

Summary of Content Analyses of Treatment Fatigue Grouped by Developmental Stage

| Terminology | Article | Developmental Factors of Treatment Fatigue |

Potential Contributing Variables |

Potential Consequences of Fatigue |

Fatigue Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children | |||||

| Medication Fatigue | Saitoh et al. (2008) | Treatment requirements, difficulty monitoring |

Pill burden | Treatment interruption, decline in CD4 cell count |

Survey of PCPa |

| Treatment Fatigue | Noguera et al. (2010) | --- | Planned treatment interruption | --- | |

| HIV-infected Children & their Caregivers | |||||

| Regimen Fatigue | Merzel et al. (2008) | Increased autonomy and opposition |

Treatment burden, increased child autonomy |

Decreased adherence | Qualitative Interview |

| Regimen Fatigue | Marhefka et al. (2006) | Fluctuates over time, onset often in first year of HAART |

Pill burden, time since regimen initiation, dosing, side effects |

Nonadherence to HAART | --- |

| Adolescents | |||||

| Treatment Fatigue | Van Dyk (2010) | Pharmacological properties | Treatment burden | Nonadherence, drug holidays | Qualitative interview |

| Adults | |||||

| Pill Fatigue | Cohen et al. (2007) | Continuous daily treatment | Continuous treatment, daily medications |

Erratic adherence, treatment failure |

--- |

| Pill Fatigue | Miron & Smith (2010) | Treatment intensity | Intense course of treatment | Drug holidays | --- |

| Pill Fatigue | Ostrop et al. (2000) | --- | Nonadherence | --- | |

| Pill Fatigue | Skiest et al. (2008) | --- | Discontinuation of HAART | --- | |

| Medication Fatigue | Ruane et al. (2003) | Complicated regimens | Decreased willingness to adhere | --- | |

| Treatment Fatigue | Arem et al. (2011) | Time since treatment initiation | Length on regimen | Decreased adherence | --- |

| Treatment Fatigue | Bagenda et al. (2011) | Prolonged treatment | Prolonged HAART | Nonadherence | --- |

| Treatment Fatigue | DiMascio et al. (2003) | Prolonged treatment | Prolonged HAART | Decreased adherence | --- |

| Treatment Fatigue | Fox et al. (2010) | --- | Nonadherence | --- | |

| Treatment Fatigue | McMahon et al. (2007) | Side effects | Side effects | Interfere with long-term treatment | --- |

| Treatment Fatigue | Miramontes (2001) | Treatment intensity, pharmacological properties, patient-provider interactions, patient characteristics |

Patient characteristics, patient- provider relationship, regimen issues (e.g., dosage, side effects) |

Discontinuation of treatment | --- |

| Treatment Fatigue | Pai et al. (2006) | --- | Nonadherence | --- | |

| Treatment Fatigue | Thompson et al. (2009) | Side effects | Side effects, regimen burden | Nonadherence | --- |

| Dosing Fatigue | Ruane et al. (2010) | Complicated regimens | Regimen burden | Decreased long-term adherence | --- |

| Drug Fatigue | Lemiale et al. (2009) | --- | --- | --- | |

| Injection Fatigue | Lalezari et al. (2003) | Number of injections | Discontinuation of treatment | --- | |

PCP = primary care provider

Table 2.

Definitions of Fatigue in Relation to HIV-Medication Adherence

| Terminology | Article | Definition of Fatigue |

|---|---|---|

| Medication Fatigue | Ruane et al. (2003) | "unwillingness to continue treatment due to the nuisance of having to take a multiplicity of doses and a high pill burden"; "loss of desire to take medication over time due to high pill burden" |

| Saitoh et al. (2008) | “patients who were unable to take antiretroviral medications because of pill burden and/or nonadherence” | |

| Regimen Fatigue | Marhefka et al. (2006) | No definition provided |

| Merzel et al. (2008) | No definition provided | |

| Treatment Fatigue | Arem et al. (2011) | “patients tiring of continually taking ART” |

| Bagenda et al. (2011) | No definition provided | |

| DiMascio et al. (2003) | No definition provided | |

| Fox et al. (2010) | No definition provided | |

| McMahon et al. (2007) | No definition provided | |

| Miramontes (2001) | “treatment fatigue is a generic term that includes aspects from all three domains: (a) patient characteristics, such as life stresses, quality of life, and cultural and health beliefs; (b) issues stemming from the patient-provider relationship, such as respect, trust, accessibility, communication, and patient satisfaction; and (c) treatment regimen issues, such as number of medications, dosing frequency, side effects, duration of therapy, impact on lifestyle, and cost” |

|

| Noguera et al. (2010) | No definition provided | |

| Pai et al. (2006) | No definition provided | |

| Thompson et al. (2009) | No definition provided | |

| Van Dyk (2010) | “taking ‘treatment holidays’; ‘emotional tiredness of taking ARVs’” | |

| Dosing Fatigue | Ruane et al. (2010) | Pill fatigue: ”unwillingness to continue treatment due to the nuisance of having to take a multiplicity of doses and a high pill burden” and “loss of desire to take medication over time due to high pill burden” |

| Pill Fatigue | Cohen et al. (2007) | No definition provided |

| Miron & Smith (2010) | No definition provided | |

| Ostrop et al. (2000) | No definition provided | |

| Skiest et al. (2008) | No definition provided | |

| Drug Fatigue | Lemiale et al. (2009) | No definition provided |

| Injection Fatigue | Lalezari et al. (2003) | “tired of giving injections” |

Etiology

Among children/adolescents, pharmacological properties, including the number of pills, hospital visits required, side effects, dosing restrictions, and time since regimen initiation, were noted as etiological factors (Marhefka, Tepper, Brown, & Farley, 2006; Merzel, VanDevanter, & Irvine, 2008; Saitoh et al., 2008; and Van Dyk, 2010). Treatment fatigue tends to fluctuate over time and may occur more frequently within the first year of treatment among children/adolescents (Marhefka et al., 2006).

Developmental characteristics have been identified as contributing factors. As children move into adolescence, adherence tends to decrease (Mellins, Brackis-Cott, Dolezal, & Abrams, 2004). Most children become aware of their HIV status after age eight or nine (Pinzón-Iregui, Beck-Sagué, & Malow, 2013) and begin to take over medication responsibilities during adolescence (Merzel et al., 2008). Challenges noted among caregivers of HIV-infected adolescents included children’s lying about taking medications and difficulty monitoring adherence during the school hours and summer months (Merzel et al., 2008; Saitoh et al., 2008). Consequently, caregivers appear to experience treatment fatigue. Among the adult population, risk and protective factors included patient characteristics (e.g., quality of life, cultural/health beliefs, life stressors) and the patient-provider relationship (e.g., mutual respect and trust, provider accessibility, communication, patient satisfaction).

Consequences

Among children/adolescents, the most commonly reported consequence is nonadherence. Among adults, pharmacological properties were identified most frequently as contributing factors (see Table 1 for citations), including pill/treatment burden and intensity of treatment, continuous daily treatment, complicated regimens, time since treatment initiation, prolonged treatment, and side effects.

Interventions

Only one study aimed to decrease treatment fatigue among children/adolescents through planned treatment interruption (PTI; Noguero et al., 2010). Significant decreases in CD4 counts and increased viral loads were reported after 12 months, suggesting PTIs are not an effective method of intervention. Within the adult population, PTIs have been used to prevent treatment fatigue (Eron et al., 2008); however, routine PTIs are discouraged due to viral replication and disease progression (Lundgren et al., 2008; Danel et al., 2006). No behavioral interventions were identified to decrease treatment fatigue among adults or children/adolescents.

Measurement

Only three studies reported quantitative or qualitative measurement of treatment fatigue. One study assessed reasons for nonadherence among children via survey administered to the primary care provider (Saitoh et al., 2008). Merzel and colleagues (2008) examined treatment fatigue among caregivers of HIV-infected children through qualitative interviews, noting that “regimen fatigue” emerged as a result of children’s opposition to taking medications as they grow older. Van Dyk (2010) surveyed 439 HIV-infected individuals via a semi-structured interview and assessed treatment fatigue using a single item labeled “treatment fatigue (i.e., taking ‘treatment holidays’)”.

Discussion

This review examined the potential causes, consequences, and characteristics of treatment fatigue among PLWH. Twenty-one relevant studies were identified. A variety of terminology was used interchangeable to address this same construct within the literature (see Table 1), the most frequent being “treatment fatigue.” However, the literature lacks consensus of an operational definition (see Table 2). Based on this review, treatment fatigue is separate from and should not be equated with nonadherence, as treatment fatigue seems to evoke its own consequences. This demonstrates the importance of developing an adequate definition of and valid and reliable measurements to assess treatment fatigue.

Developmental factors appear to be associated with treatment fatigue (see Table 1). Specifically, these studies highlighted pill burden (e.g., number/size of pills) as contributing to treatment fatigue in children. As children move into adolescents it appears that increased autonomy may play a stronger role in treatment fatigue. Among caregivers of HIV-infected children/adolescents, oppositional behaviors such as lying, refusing to take medications, and difficulty monitoring adherence contribute to caregivers’ experience of treatment fatigue. Finally, among adults, the literature suggests that pill burden and patient-provider interaction play a role in the development of treatment fatigue.

To date, only pharmacological interventions using structured treatment interruptions have been examined to decrease treatment fatigue; however, these interventions are not recommended due to increased morbidity and mortality risk. Behavioral interventions, tailored to developmental stage, may provide a platform to address factors associated with treatment fatigue. Further, patients newly prescribed treatment regimens may benefit from education about treatment fatigue and development of skills to prevent its occurrence. Timing, delivery method, and dose response should be considered prior to intervention development. Treatment fatigue is not a one-time, static experience, but occurs at multiple times throughout the patient’s life.

This review highlights the paucity of research on and understanding of treatment fatigue. Synthesis of existing terminology describing this construct is needed. The most widely used term that described this concept was “treatment fatigue.” Unfortunately, this term frequently represents the physiological construct of fatigue as a consequence of disease or medication side effects and may result in confusion among disciplines. The authors propose use of the term “treatment regimen fatigue” to represent the psychological fatigue associated with long-term treatment. Consolidation of a definition is an important foundation for future investigations. The authors propose the following operational definition of treatment regimen fatigue: decreased desire and motivation to maintain vigilance in adhering to a treatment regimen as prescribed by a provider.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, this review only targeted PLWH in order to minimize confounding variables in the development of the concept. Second, this review is not intended to be an exhaustive review of the literature. The lack of consistent terminology used to identify treatment fatigue in the literature makes it plausible that some articles were not identified that examined this construct. However, the authors used a variety of search terms that are commonly used in the HIV literature related to this construct, consulted with healthcare providers regarding terms used within the clinic setting, and examined literature from other chronic illness populations to determine appropriate search terms in an effort to include as many relevant studies as possible. Third, the lack of established research resulted in a small number of studies meeting inclusion criteria for the current study, which limits the ability to draw conclusions. Finally, the quality of construct measurement, either qualitatively or quantitatively, in the included studies is not optimal for accurately defining treatment regimen fatigue.

This review details the emergence of treatment fatigue in the HIV literature and takes the first step towards defining and identifying its etiology and consequences. Future research should seek to develop a valid and reliable measure of treatment fatigue. Examination of caregivers’ experience of treatment fatigue for HIV-infected children and adults is important. Further study regarding the etiology, maintenance, and life course of treatment fatigue is expected to aid intervention efforts.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by grant number T32 AA007459 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism at the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Arem HN, Nakyanjo N, Kagaayi J, Mulamba J, Nakigozi G, Serwadda D, Chang LW. Peer health workers and AIDS care in Rakai, Uganda: A mixed methods operations research evaluation of a cluster-randomized trial. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2011;25:719–724. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagenda A, Barlow-Mosha L, Bagenda D, Sakwa R, Fowler MG, Musoke PM. Adherence to tablet and liquid formulations of antiretroviral medication for paediatric HIV treatment at an urban clinic in Uganda. Annals of Tropical Paediatrics. 2011;31:235–245. doi: 10.1179/1465328111Y.0000000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwickl B, Wu AW. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: The AACTG Adherence Instruments. AIDS Care. 2000;12:255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CJ, Colson AE, Sheble-Hall AG, McLaughlin KA, Morse GD. Pilot study of a novel short-cycle antiretroviral treatment interruption strategy: 48-week results of the five-days-on, two-days-off (FOTO) study. HIV Clinical Trials. 2007;8:19–23. doi: 10.1310/hct0801-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PF, Sousa KH, et al. Patterns of change in symptom clusters with HIV disease progression. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2011;42:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danel C, Moh R, Minga A, Anzian A, Ba-Gomis O, Kanga C, Anglaret X. CD4-guided structured antiretroviral treatment interruption strategy in HIV-infected adults in west Africa (Trivacan ANRS 1269 trial): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;367(9527):1981–1989. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMascio M, Markowitz M, Louie M, Hogan C, Hurley A, Chung C, Ho DD, Perelson AS. Viral blip dynamics during highly active antiretroviral therapy. Journal of Virology. 2003;77:12165–12172. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.22.12165-12172.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eron J. Managing antiretroviral therapy: changing regimens, resistance testing, and the risks from structured treatment interruptions. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008;197(Suppl 3):S261–S271. doi: 10.1086/533418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MP, McCoy K, Larson BA, Rosen S, Bii M, Sigei C, Simon JL. Improvements in physical wellbeing over the first two years on antiretroviral therapy in Western Kenya. AIDS Care. 2010;22:137–145. doi: 10.1080/09540120903038366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedland GH. HIV medication adherence. The intersection of biomedical, behavioral, and social science research and clinical practice. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2006;43(Suppl 1):S3–S9. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248333.44449.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner EM, Burman WJ, Maravi ME, Davidson AJ. Durability of Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy on Initial and Subsequent Regimens. AIDS Patient Care And Stds. 2006;20(9):628–636. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics JR, Meade CS. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among patients with HIV: A critical link between behavioral and biomedical sciences. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2002;31S:98–102. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200212153-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MO, Stallworth T, Neilands TB. The drugs or the disease? Causal attributions of symptoms held by HIV positive adults on HAART. AIDS and Behavior. 2003;7:109–117. doi: 10.1023/a:1023938023005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalezari JP, DeJesus E, Northfelt DW, Richmond G, Wolfe P, Haubrich R, Delehanty J. A controlled Phase II trial assessing three doses of enfuvirtide (T-20) in combination with abacavir, amprenavir, ritonavir, and efavirenz in non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-naïve HIV-infected adults. Antiviral Therapy. 2003;8:279–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemiale F, Korokhov N. Lentiviral vectors for HIV disease prevention and treatment. Vaccine. 2009;27:25–26. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren J, Babiker A, El-Sadr W, Emery S, Grund B, Neaton J, Phillips A. Inferior clinical outcome of the CD4+ cell count-guided antiretroviral treatment interruption strategy in the SMART study: role of CD4+ Cell counts and HIV RNA levels during follow-up. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008;197(8):1145–1155. doi: 10.1086/529523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marhefka SL, Tepper VJ, Brown JL, Farley JJ. Caregiver psychosocial characteristics and children’s adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2006;20:429–437. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon D, Lederman M, Haas DW, Haubrich R, Stanford J, Cooney E, Horton J, Mellors JW. Antiretroviral activity and safety of abacavir in combination with selected HIV-1 protease inhibitors in therapy-naïve HIV-1-infected adults. Antiviral Therapy. 2001;6:105–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellins C, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Abrams E. The role of psychosocial and family factors in adherence to antiretroviral treatment in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2004;23(11):1035–1041. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000143646.15240.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merzel C, VanDevanter N, Irvine M. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among older children and adolescents with HIV: A qualitative study of psychosocial contexts. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2008;22:977–987. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miramontes H. Treatment fatigue. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2001;12S:90–92. doi: 10.1177/105532901773742356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miron RE, Smith RJ. Modelling imperfect adherence to HIV induction therapy. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2010;10:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguero A, Moren C, Rovira N, Sanchez E, Garrabou G, Nicolas M, Fortuny C. Evolution of mitochondrial DNA content after planned interruption of HAART in HIV-infected pediatric patients. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2010;26:1015–1018. doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrop NJ, Hallett KA, Gill MJ. Long-term patient adherence to antiretroviral therapy. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2000;34:703–709. doi: 10.1345/aph.19201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai NP, Lawrence J, Reingold AL, Tulsky JP. Structured treatment interruptions (STI) in chronic unsuppressed HIV infection in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;3:CD006148. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, Singh N. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2000;133(1):21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinzón-Iregui M, Beck-Sagué C, Malow R. Disclosure of their HIV status to infected children: a review of the literature. Journal Of Tropical Pediatrics. 2013;59(2):84–89. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fms052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruane PJ, Parenti DM, Margolis DM, Shepp DH, Babinchak TJ, Van Kempen AS, Hernandez JE. Compact quadruple therapy with the lamivudine/zidovudine combination tablet plus abacavir and efavirenz, followed by the lamivudine/zidovudine/abacavir triple nucleoside tablet plus efavirenz in treatment-naïve HIV-infected adults. HIV Clinical Trials. 2003;4:231–243. doi: 10.1310/MM9W-BAU0-BT6Q-401B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh A, Foca M, Viani RM, Heffernan-Vacca S, Vaida F, Lujan-Zilbermann J, Spector SA. Clinical outcomes after an unstructured treatment interruption in children and adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV infection. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e513–e521. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skiest DJ, Krambrink A, Su Z, Robertson KR, Margolis DM. Improved measures of quality of life, lipid profile, and lipoatrophy after treatment interruption in HIV-infected patients with immune preservation: Results of ACTG 5170. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2008;49:377–383. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818cde21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson IR, Bidgood P, Petroczi A, Denholm-Price JC, Fielder MD. An alternative methodology for the prediction of adherence to anti-HIV treatment. AIDS Research and Therapy. 2009;6:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyk AC. Treatment adherence following national antiretroviral rollout in South Africa. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2010;9:235–247. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2010.530177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]