Abstract

Risk-taking behavior increases during adolescence, leading to potentially disastrous consequences. Social anxiety emerges in adolescence and may compound risk-taking propensity, particularly during stress and when reward potential is high. However, the manner in which social anxiety, stress, and reward parameters interact to impact adolescent risk-taking is unclear. To clarify this question, a community sample of 35 adolescents (15 to 18 yo), characterized as having high or low social anxiety, participated in a 2-day study, during each of which they were exposed to either a social stress or a control condition, while performing a risky decision-making task. The task manipulated, orthogonally, reward magnitude and probability across trials. Three findings emerged. First, reward magnitude had a greater impact on the rate of risky decisions in high social anxiety (HSA) than low social anxiety (LSA) adolescents. Second, reaction times (RTs) were similar during the social stress and the control conditions for the HSA group, whereas the LSA group’s RTs differed between conditions. Third, HSA adolescents showed the longest RTs on the most negative trials. These findings suggest that risk-taking in adolescents is modulated by context and reward parameters differentially as a function of social anxiety.

Keywords: gambling, wheel of fortune, expected value, uncertainty, youths

1. Introduction

Adolescence is a developmental period that is marked by the emergence of a number of risky, potentially hazardous behaviors, such as substance use, risky sexual activity, or reckless driving (e.g., DiClemente et al., 1996; Gullo & Dawe, 2008; Windle et al., 2008), all of which potentially leading to disastrous outcomes (Hingson, Heeren, Winter, & Wechsler, 2005). All risky behaviors assume a level of conflict since they involve the weighting of potential risks vs. benefits. That is, although these behaviors may be expected to bring enjoyment (reward), they can also lead to devastating consequences. The subjective estimate of the risk/benefit ratio varies across individuals and contexts, and may also be modulated by the reward parameters (e.g., probability, magnitude).

Social anxiety, which is particularly prominent in adolescence (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), may be an important individual factor that can influence the perceived risks vs. benefits of certain situations (i.e., social interactions), which subsequently may impact an individual’s propensity toward risky decision-making and risk-taking. Social anxiety involves fear and avoidance of social contexts that carry the potential for judgment or rejection by others. Accordingly, individuals with social anxiety are typically shy, behaviorally inhibited, and risk averse (e.g., Beidel & Turner, 1998). Presumably, this temperamental pattern should limit one’s exposure to risky situations, such as joining substance-using peer groups (Fergusson & Horwood, 1999) or attending risky social events (Myers, Aarons, Tomlinson, & Stein, 2003).

However, an emerging line of research indicates that social anxiety can also be paradoxically associated with disinhibited or risk-prone behaviors, including aggression, unsafe sexual practices, drinking and abusing alcohol, and impulsive decision-making (Buckner, Eggleston, & Schmidt, 2006; Erwin, Heimberg, Schneier, & Liebowitz, 2003; Hanby, Fales, Nangle, Serwik, & Hedrich, 2012; Kashdan, Elhai, & Breen, 2008; Kashdan & Hofmann, 2008; Kashdan & McKnight, 2010; Kashdan, McKnight, Richey, & Hofmann, 2009; Rounds, Beck, & Grant, 2007; Schneier et al., 2010). These seemingly discrepant findings suggest that the relationship between social anxiety and risk-taking may be modulated by additional factors, such as features of the social context and/or the probability or magnitude of potential rewards.

With regard to the social context, evidence suggests that when socially anxious individuals encounter situations involving social threat (either real or perceived), their behavioral response might switch from a risk-averse to a risk-prone pattern. For example, Muris and colleagues (2000a; 2000b) reported that children and adolescents with social anxiety were more likely to perceive ambiguous social cues (e.g., a neutral facial expression) as threatening, and, when feeling threatened, to react with aggression (Muris, Merckelbach, & Walczak, 2002). One interpretation is that, when socially anxious individuals are unable to use their typical avoidance-related coping strategies, they may engage in risky behaviors (e.g., substance use, aggression) as an alternative strategy to cope with the real or imagined threat of social rejection.

In addition to social threat, the potential rewards associated with risk-taking may also contribute to tipping the risk/benefit ratio in favor of benefits, which would promote the adoption of risky behaviors. For example, among socially anxious individuals, stronger beliefs that potentially risky situations (e.g., substance use) have the potential for substantial rewards (e.g., enhancing social standing) have been linked with more frequent engagements in social interactions, including risky sexual behavior, aggression, and substance use (Kashdan et al., 2008). Additionally, individuals with high social anxiety are more likely to report wanting to drink because of the positive reinforcement (i.e., to enhance positive affect and experiences), but not negative reinforcement (i.e., to reduce negative affect) aspects of alcohol consumption, relative to people with low social anxiety (Kashdan et al., 2008). Moreover, the degree to which individuals endorse drinking specifically for these rewarding aspects is associated with alcohol-related problems (Buckner et al., 2006). Thus, socially anxious individuals seem to be particularly sensitive to the potential for rewards (positive reinforcement) associated with risk-taking. Consequently, when they believe the potential for reward to be high, they display more risky behaviors than would normally be expected based on traditional characterizations of social anxiety as being associated with risk-avoidance. Despite the apparent importance of rewards in determining if and when socially anxious individuals will take risks, to our knowledge, no studies to date have systematically manipulated reward parameters (e.g., probability, magnitude) to quantify their influence on risky decision-making among individuals with social anxiety across varying social contexts.

As a first step in this direction, we recently used an experimental approach to examine risk-taking behavior in real-time as a function of social context (i.e., acute social stress) among individuals characterized by their social anxiety status, but without manipulating reward parameters (Reynolds et al., 2013). Adolescents with high social anxiety took more risks (on the Balloon Analog Risk Task) when exposed to social stress compared to a low-stress, control context. Conversely, adolescents with low social anxiety failed to show any increase in risktaking during the social stress vs. the control context. Although this study supports the notion that in certain contexts (i.e., overt, inescapable social stress), social anxiety may actually be a risk factor rather than a protective factor for engaging in risky behavior, it remains unclear how the characteristics of potential rewards further differentiate risky decision-making between anxious vs. non-anxious individuals. The present study addresses this gap.

Using a within-subjects design, adolescents, characterized as having low or high social anxiety, performed a risk-taking task twice on two separate days. On one day, participants were exposed to a social stress condition, and on the other day to a low-stress control condition. The risk-taking task utilized was the Wheel of Fortune Task (WOF; Ernst et al., 2004). This task assesses risky decision-making by manipulating the magnitude and probability of rewards orthogonally across trials. The goal of this study was to examine the effects of social anxiety, acute social stress, and reward parameters on risky decision-making among adolescents.

Based on the reviewed literature, we hypothesized that, relative to low social anxiety (LSA), high social anxiety (HSA) would be associated with more “inhibited” or risk-avoidant tendencies (longer reaction times and fewer risky decisions) in the control condition. However, in the social stress condition, HSA would be associated with increased risky behaviors (shorter reaction times and more risky decisions). In addition, we expected that the probability and magnitude of potential rewards would modulate these findings. Generally, a higher probability or magnitude of reward would intensify these group differences as a function of the stress condition.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

This study was conducted as part of a larger investigation of adolescent anxiety and risk-taking behavior (Reynolds et al., 2013). Thirty-nine English-speaking participants, 15 to 18 years old (Mean = 16.0; SD = 1.1), were recruited from the greater metropolitan Washington D.C. area. Most of these participants were also included in the published study by Reynolds and colleagues (2013). All study sessions were conducted at the University of Maryland College Park. Of the 39 participants recruited, four participants had missing data due to technical difficulties and were excluded from the analyses. The final sample of 35 participants (11 male) was 25.7% Caucasian (n = 9), 60% African American (n = 21), and 14.3% mixed race or other (n = 5).

2.2 Procedure

Permission to conduct research was obtained from the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board (IRB). Informed consent/assent was acquired from all participants and their legal guardian prior to initiating study procedures. Participants completed the study in two sessions, scheduled 3 to 14 days apart. Each session included one of two experimental conditions. One session involved a social stress condition, while the other session involved a low-stress, control condition (see Section 2.3 below for descriptions of experimental conditions). Session order was randomized across participants to control for order effects. Computer tasks designed to assess decision-making and risk-taking were administered once at each session. Here, we focus on the monetary WOF computer task (Roy et al., 2011).

2.3 Experimental Conditions

2.3.1 Social Stress Session

Each session began with a baseline assessment of various affective states, including, but not limited to, anxiety (see Section 2.4.2). In the Social Stress session, participants were told that they would give a three-minute speech in front of a group of judges after completing computer tasks. They were informed that the judges would evaluate and provide feedback on their performance. As part of the instructions, participants were shown a video with actors representing other adolescent participants giving speeches in front of judges. In most instances, the actor in the video made multiple errors and became progressively more anxious. Participants were told that one of three possible speech topics would be randomly selected. The three prompts were 1) Should girls be allowed to play on boys sports teams? 2) If you could have voted in the last presidential election, who would you have voted for and why? and 3) Describe your personality, both your strengths and weaknesses. After hearing the speech instructions, participants completed a second set of affective ratings, followed by a battery of computer tasks. Participants were instructed to prepare their speech for three minutes in between each computer task. Two additional assessments of affective state were collected (1) after computer task completion (directly prior to giving the speech), and (2) directly after the speech.

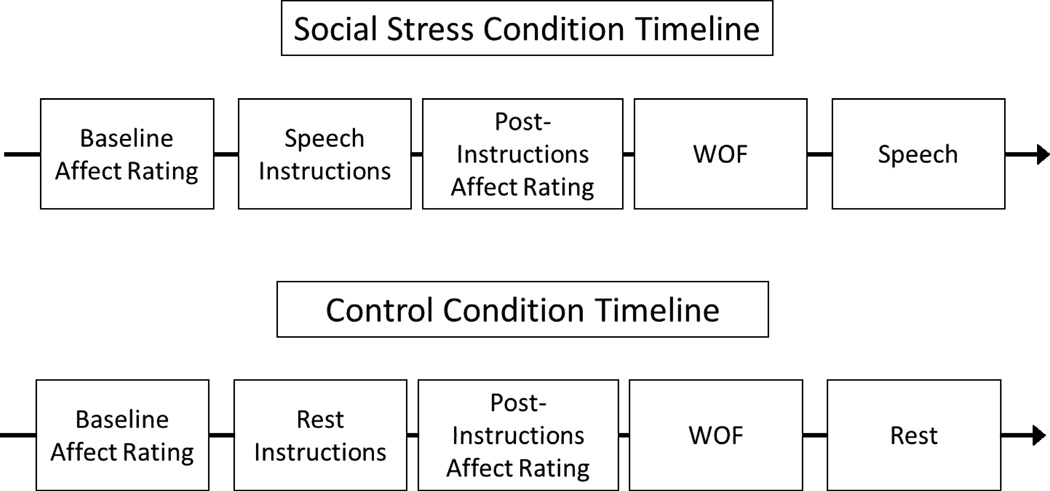

2.3.2 Control Session

During the Control session, participants did not prepare or deliver a speech, but instead were given a three-minute period of rest, which involved sitting quietly in a comfortable chair, in between computer tasks, and again following task completion. Prior to completing the baseline measure of mood state, participants were explicitly told that they would not give a speech. Additional assessments of affective state were collected (1) after being given instructions about the rest period that would follow the computer tasks, (2) after completion of all computer tasks, and (3) after the rest period (see Figure 1 for an illustration of the experimental procedure).

Figure 1.

Diagrams illustrating the procedures employed in each of the experimental conditions. The Social Stress condition involved providing instructions to participants about a speech they would be asked to make in front of a panel of judges, while the Control condition involved a period of rest. Affect ratings collected at Baseline and Post-Instructions were used to assess the effectiveness of the experimental manipulation for inducing stress. The Wheel of Fortune task was used to measure risky decision-making.

2.4 Measures

2.4.1 Wheel of Fortune task

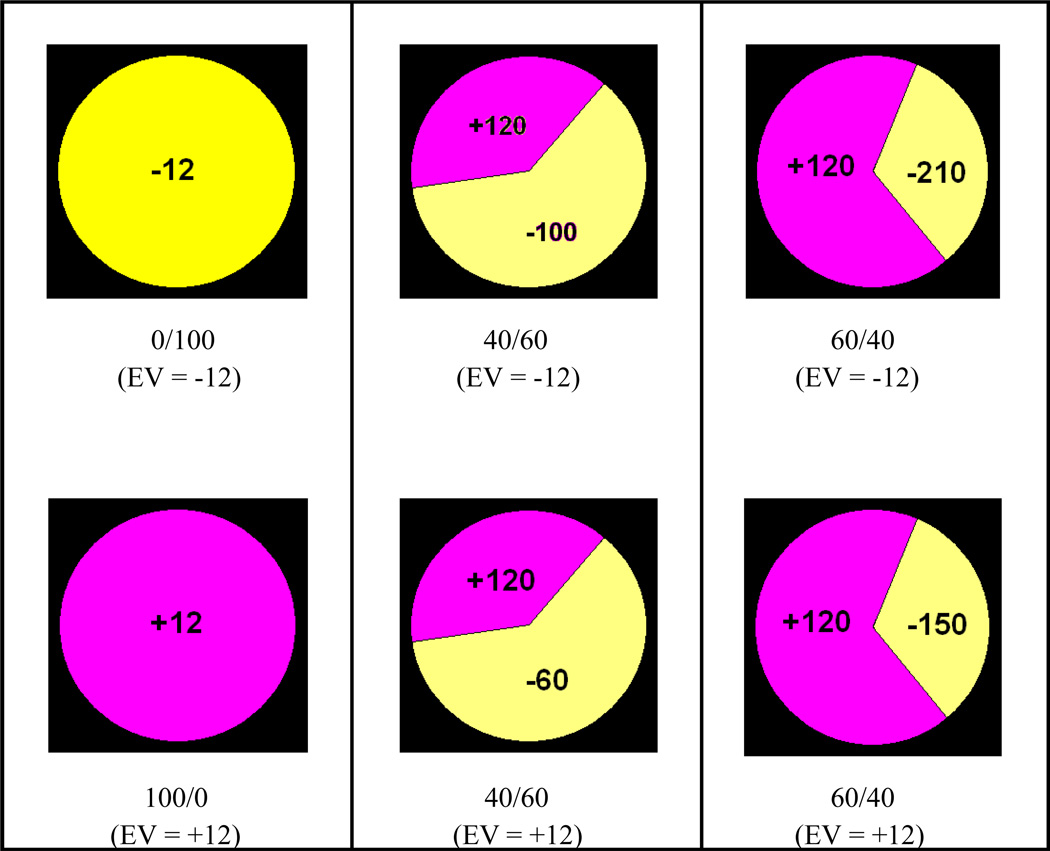

The WOF task (Roy et al., 2011) was designed to measure risky decision-making. Participants were given the opportunity to win points by betting on the outcome of wheel rotations. The wheels consisted of pink and yellow sections, displayed in four different ratios (100/0, 60/40, 40/60, 0/100) (see Figure 2). On a given trial, one area displayed the number of points participants could win, while the other area displayed the number of points participants could lose. The colors (i.e., pink vs. yellow) were assigned to the “win” and “lose” areas for the WOF version 1, and to the “lose” and “win” areas for the WOF version 2. Version 1 and version 2 were randomly distributed across subjects to control for a potential color effect. The 100/0 and 0/100 wheels were used as no-risk comparisons, providing a 100% chance of a 12-point win with a 0% chance of loss (100/0), and a 0% chance of gain with a 100% chance of a 12-point loss (0/100), respectively. The risky wheels included the 40/60 wheel, which provided a 40% chance of win with a 60% chance of loss, and the 60/40 wheel, which provided a 60% chance of win with a 60% chance of loss. The number of points in the “win” sections on risk trials did not vary and was set to 120 points. However, the number of points displayed in the loss section did vary across risk trials (i.e., 60, 100, 150, or 210 points), creating two levels of expected values (EV), +12 (positive) and −12 (negative) (e.g., a wheel presenting a 40% chance of winning 120 points and a 60% chance of losing 100 points has an EV= (0.40 × 120) + (0.60 × −100) = (48) + (−60) = −12 (negative EV)). Each of the 40/60 (positive EV and negative EV) and 60/40 (positive EV and negative EV) wheels was presented 22 times, and each of the 100/0 and 0/100 was presented 8 times, across 4 blocks. The order of wheels was randomized across the whole task. EVs were not discussed with the participants. However, the participants were told that points represented some dollar value that could be won or lost. Participants could earn an extra $2.50 to $10 depending on their performance on the WOF task. This amount was determined based on the outcome of three randomly selected trials after task completion (as was explained to the participants beforehand).

Figure 2.

Diagram illustrating each of the trial types that participants were exposed to during the Wheel of Fortune (WOF) task. Trials varied by probability (0/100; 100/0; 40/60; 60/40) and expected value (EV; positive and negative)

Participants had the option to Bet or Pass on every wheel presented. They could choose to Bet by pressing “1” or Pass by pressing “2” on a keyboard while the wheel was displayed. The wheel then spun. An arrow on the outside of the wheel indicated which section had been “landed” on. In order to earn points, participants had to Bet, and the arrow then had to land on the “win” section of the wheel. Participants would lose points if they Bet and the arrow landed on the “loss” section of the wheel. Choosing to Pass resulted in neither a gain nor loss in points, regardless of where the arrow landed on the wheel. The decision-making period was limited to three seconds. If participants did not indicate a choice in the allotted time, that trial was assigned its loss value.

Measures of risk-taking performance on the WOF task were (1) percentage of bets (PCbets) and (2) reaction times (RTs). Higher PC-bet and shorter RTs on trials presumably infer higher risk-taking propensity.

2.4.2 Self-report Measures

We used the sum of the four most relevant negative affect items from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988), “upset,” “angry,” “frustrated” and “anxious,” to measure the effectiveness of stress induction during the Social Stress session. Participants were asked to rate each item on a 5-point scale, from 1 (never/not at all) to 5 (always/very much), to reflect how much they were experiencing each emotion in the present moment, with higher scores indicating greater levels of negative affect. Affect ratings collected at baseline (i.e., before receiving instructions) and after receiving the instructions were used to check the effectiveness of the experimental manipulation as a stress induction method (see Figure 1).

The Abbreviated Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory (SPAI-23; Roberson-Nay, Strong, Nay, Beidel, & Turner, 2007) is a 23-item scale derived from the Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory (Beidel, Borden, Turner, & Jacob, 1989). Participants were asked to rate each item on a 5-point scale, ranging from 0 (Never) to 4 (Always). The SPAI-23 has been used in both normal and clinical populations, and highly correlates with the SPAI (r =.88), which has been widely used and has excellent psychometric properties with both adults and adolescents. For the current study, the social phobia subscale of the SPAI-23 was used to index severity of social anxiety.

2.5 Data Analysis

Only valid trials (RT’s > 200 ms) were analyzed. In addition, social anxiety severity was dichotomized using a median-split method to facilitate post-hoc investigations of significant interactions using the linear mixed effects (LME) models. The median of the SPAI-23 scores was 18. The low social anxiety (LSA) group (n = 18) was composed of individuals with SPAI-23 scores ranging from 0 to18 (Mean = 8.78; SD = 6.58) and the high social anxiety (HSA) group (n = 17) included individuals with SPAI-23 scores ranging from 19 to 38 (Mean = 24.47; SD = 4.59). Although the HSA group was significantly more socially anxious than the LSA group (t(33) = 7.92; p< .001), most participants did not reach clinical levels of social anxiety (the suggested SPAI-23 clinical cut-off for clinical anxiety = 28; three HSA individuals scored 28 or above) (Schry, Roberson-Nay, & White, 2012). All analyses were conducted using SPSS, and significant effects were set at p < .05.

We first conducted analyses to verify that the stress manipulation worked. Accordingly, scores on the self-reported negative affect scales were compared between the Social Stress and Control conditions. To assess potential variables that could confound the results, the effects of demographic characteristics (i.e., age, SES, sex) and session order were examined on performance measures (PC-bets and RTs).Finally, only data from the risky trials (i.e., 40/60, 60/40) were analyzed given our specific interest in risky decision-making. To examine the interactions among social condition, reward parameters, and social anxiety group status, separate LME models were conducted for PC-bets and RTs respectively.

3. Results

3.1 Quality Control Analyses

3.1.1 Manipulation Check

We first examined whether the social-stress induction had the desired effect. Seven participants were missing affective ratings at baseline during the Control session, and two participants were missing affective ratings at baseline during the Social Stress session; therefore, manipulation check analyses were conducted on the remaining 26 participants. All participants were included in subsequent analyses.

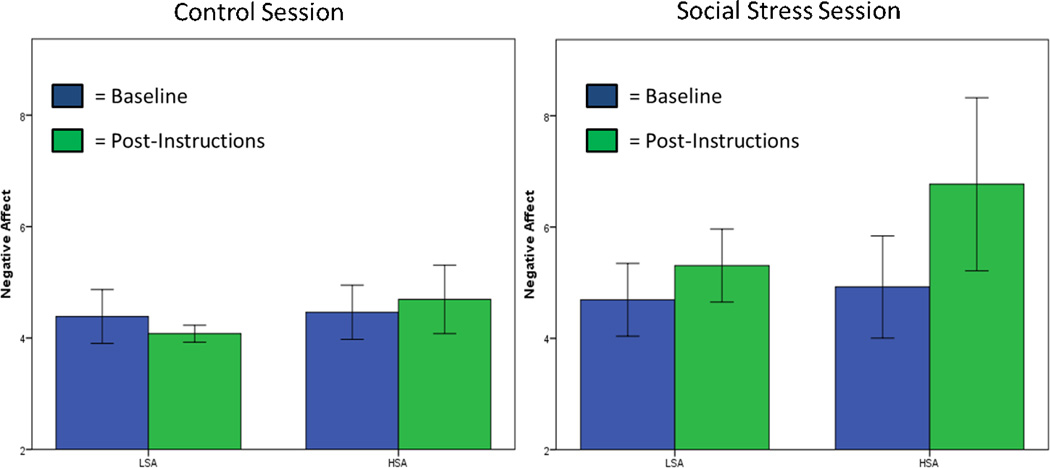

We conducted a three-way repeated measures analysis of variance with Condition (Social Stress vs. Control) and Time (Baseline vs. Post-Instructions) as within-subject variables and Group (LSA vs. HSA) as the between-subjects variable to examine the effects of the experimental manipulation on negative affect (sum of “anxious”, “angry”, “frustrated”, and “upset” ratings on the PANAS) (Figure 3; Table 1). Results revealed several interactions and main effects consistent with successful stress manipulation.

Figure 3.

Negative affect ratings at Baseline and Post-Instructions across both experimental conditions, as a function of social anxiety group.

Note: error bars represent ± SEM; LSA = low social anxiety; HSA = high social anxiety

Table 1.

Three-way (Group by Condition by Time) Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance Predicting Negative Affect based on PANAS ratings.

| Source | df | F | η2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between subjects | ||||

| Group (G) | 1 | 1.75 | .07 | .20 |

| Within subjects | ||||

| Condition (C) | 1, 24 | 23.91*** | .50 | .001 |

| Time (T) | 1, 24 | 7.80** | .25 | .01 |

| CxT | 1, 24 | 20.11*** | .46 | .001 |

| CxG | 1, 24 | 1.44 | .06 | .24 |

| TxG | 1, 24 | 4.30* | .15 | .05 |

| CxGxT | 1, 24 | 1.50 | .06 | .23 |

Note:

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001

First, the stress manipulation worked for both groups, as revealed by a significant Condition-by-Time interaction (F(1, 24)= 20.1; p <.001) (see Table 1 and Figure 3). On average across both groups, negative affect increased from Baseline to Post-Instructions in the Social Stress condition, but there was no change in negative affect during the Control condition. Second, as expected, the HSA group relative to the LSA group was more sensitive to the stressful nature of the experiment overall, as indicated by a significant Group-by-Time interaction (F(1, 24) = 4.30; p = .049). On average across the two sessions, negative affect significantly increased from Baseline to Post-Instructions in HSA individuals, but not in LSA individuals (see Table 1).

3.1.2 Task Engagement

Participants provided responses (Bet or Pass) to 98.1% of trials, with no significant differences in the number of responses between the Social Stress and Control session (χ2 = .429; p = .512), or as a function of social anxiety (χ2 = .965; p = .326), suggesting adequate engagement on the task during both testing sessions and across levels of social anxiety severity.

3.1.3 Potential Confounding Variables

Next, we tested the effects of several potential confounding variables, including age, gender, trial number, and session order on WOF task performance (i.e., RT and PC-bets). None of the demographic variables were correlated with PC-bets or RTs. However, session order (t(7919) = 10.55; p < .001), and trial number (F(25, 7895) = 3.09; p < .001) significantly influenced RTs, but not PC-bets. Regarding session order, participants who were exposed to the Control session first, exhibited significantly slower RTs overall (across both sessions) compared to participants who were exposed to the Social Stress session first. Regarding trial number across the whole task, RTs became slower on later trials of the task. Thus, session order and trial number were used as covariates of nuisance in all analyses of RTs. No covariates were included in analyses of PC-bets.

3.2 Performance Analyses

3.2.1 Percentage of Bets (PC-bets)

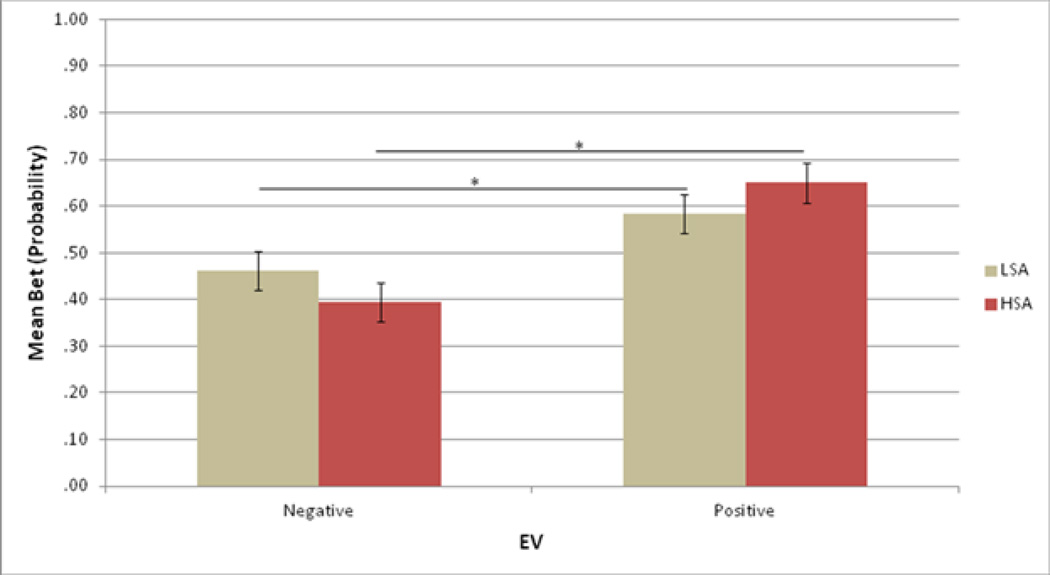

We used a 4-way LME model with Group (LSA, HSA) as the between-subjects factor, and Condition (Social Stress, Control), Probability (40/60, 60/40), and EV (positive, negative) as within-subject factors to predict PC-bets. The 4-way LME model revealed a significant Group-by-EV interaction and a main effect of Probability on PC-bets. No other interactions or main effects reached statistical significance. Notably, the social stress manipulation had no effect on PC-bets.

The modulation of PC-bets by Group and EV (F(1, 244.599) = 4.079; p < .05) (Figure 4) indicated that the HSA group showed a more pronounced increase in PC-bets on positive EV trials relative to negative EV trials compared to the LSA group, although both groups bet more frequently on positive than negative EV trials (F(1, 244.599) = 32.798; p< .001).

Figure 4.

Bar graph illustrating a significant Group-by-EV interaction predicting PC-bets. HSA showed a relatively steeper increase in PC-bets on positive EV than negative EV trials compared to LSA, although both groups bet more frequently on positive EV than negative EV trials.

Note: *p < .01, error bars represent ± SEM; EV = expected value; PC-bets = percentage of bets; HSA = high social anxiety; LSA = low social anxiety

In addition, as expected, the significant main effect of Probability reflected that both groups bet more on 60/40 than 40/60 trials (F(1, 121.414) = 80.332; p< .001).

3.2.2 Reaction Times

RT was analyzed using 5-way LME modeling, with Group (LSA, HSA) as the betweensubjects factor, and Condition (Social Stress, Control), Probability (40/60, 60/40), EV (positive, negative), and Decision (Bet, Pass) as the within-subjects factors. Since this study focuses on decision-making in anxiety, only the significant results involving Group and Condition will be highlighted (Table 2).

Table 2.

Significant interactions and main effects from a 5-way (Group by Condition by EV by Probability by Decision) linear mixed effects model predicting RTs on probabilistic trials. The first five columns indicate which factors are included in each interaction or main effect (signified with an X). The sixth column presents the F test for the corresponding interaction (e.g., the first row corresponds to the significant 3-way Group-by-Condition-by-Decision interaction with an F = 9.674). The shading of the rows reflects the complexity of the interactions: 3-way interactions are in dark grey, 2-way interactions are in light grey, and main effects are in white.

| Group | Condition | EV | Probability | Decision | Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | X | X | (F(1,4613.425) = 9.674, p < .01) | ||

| X | X | X | (F(1,6395.491) = 4.408, p < .05) | ||

| X | X | X | (F(1,6583.853) = 5.925, p < .05) | ||

| X | X | (F(1,6411.355) = 9.807, p < .01) | |||

| X | X | (F(1,4599.35) = 15.131, p < .001) | |||

| X | (F(1,6410.171) = 8.275, p < .01) |

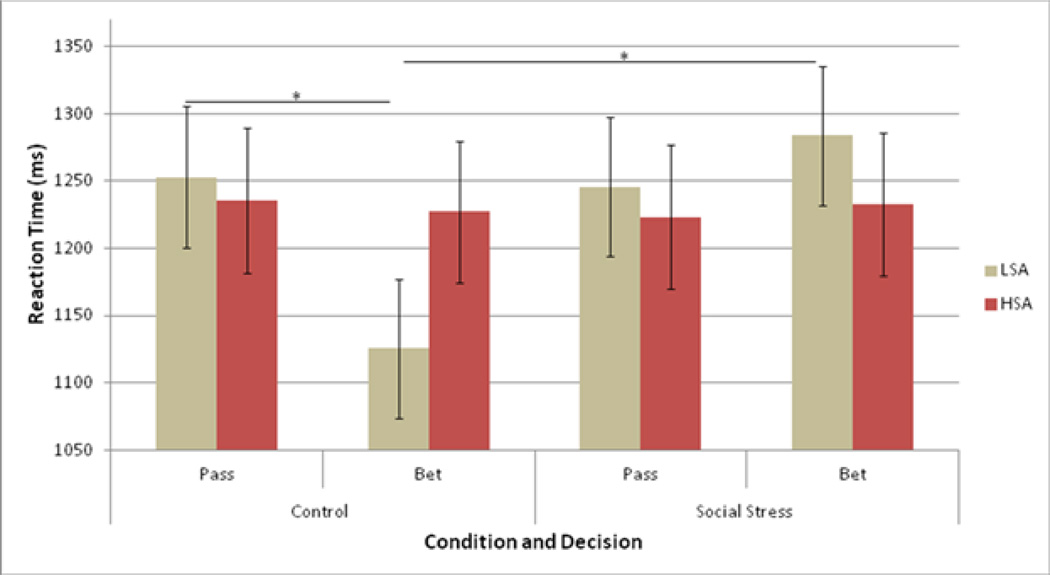

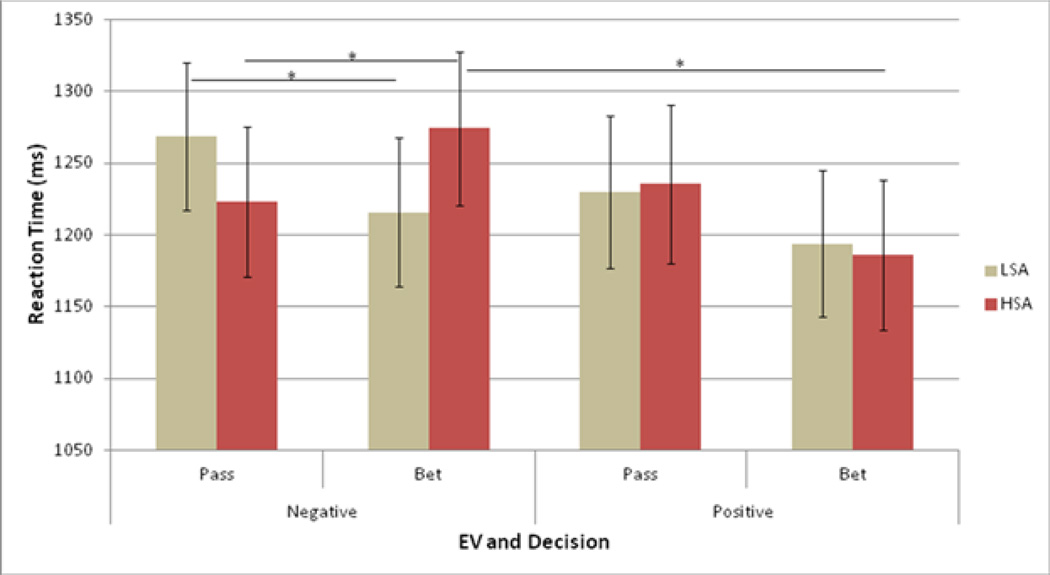

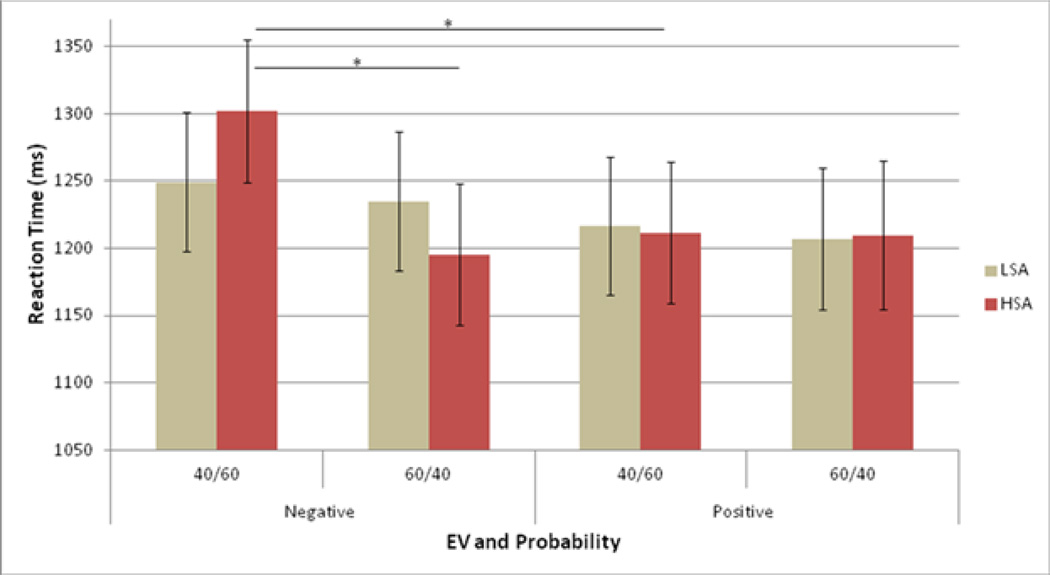

The LME analysis revealed three significant 3-way interactions of Group-by-Condition-by-Decision (F(1, 4613.425) = 9.674; p < .01) (Figure 5), Group-by-EV-by-Decision (F(1, 6583.853) = 5.925; p < .05) (Figure 6), and Group-by-EV-by-Probability (F(1, 6395.491) = 4.408; p < .05) (Figure 7). These interactions reflected three types of modulation of RT by Group.

Figure 5.

Significant Group-by-Condition-by-Decision interaction predicted RTs. Specifically, the LSA group showed shorter RTs when betting relative to passing during the Control condition, but not during the Social Stress condition. Within the HSA group, RTs did not differ regardless of decision (Bet vs. Pass), nor condition (Social Stress vs. Control).

Note: *p < .001, error bars represent ± SEM; RTs = reaction times; LSA = low social anxiety; HSA = high social anxiety

Figure 6.

Significant Group-by-EV-by-Decision interaction predicted RTs. On negative EV trials only, the LSA group was slower to pass than to bet, while the HSA group was faster to bet than to pass. No group differences in RTs were seen on positive EV trials, regardless of decision (i.e., bet vs. pass).

Note: *p < .05, error bars represent ± SEM; RTs = reaction times; LSA = low social anxiety; HSA = high social anxiety

Figure 7.

Significant Group-by-EV-by-Probability interaction predicted RTs. The HSA group showed the longest RTs on the most negative trials (i.e., 40% probability of winning in negative EV trials). The LSA group showed no effect of either EV or probability on their RTs.

Note: *p < .001, error bars represent ± SEM; RTs = reaction times; LSA = low social anxiety; HSA = high social anxiety

First, the Group-by-Condition-by-Decision interaction (Figure 5) was decomposed by Group. The LSA group showed a differential sensitivity to the type of decision they made (Bet vs. Pass) in the Control condition. Specifically, they were faster to Bet than to Pass (p < .001). However, this was not present in the Social Stress condition. In contrast, the HSA group showed no sensitivity to the decision they made in either the Social Stress or Control condition.

Second, we examined the Group-by-EV-by-Decision interaction (Figure 6). The HSA and LSA groups differed in their response to negative EV trials only, such that the LSA group was slower to Pass than to Bet (p < .05), while the HSA group was slower to Bet than to Pass (p < .05) on negative EV trials. However, both groups had similar betting and passing response times on positive EV trials. Lastly and of interest, the HSA group’s response time to bet was significantly slower for negative EV trials than for positive EV trials (p < .001), which was not the case in the LSA group.

Third, we examined the Group-by-EV-by-Probability interaction (Figure 7). This interaction revealed that the HSA group was sensitive to the probability of winning (40% vs. 60%) in the negative EV trials (slower RTs on low win-probability trials (40% trials) than on high win-probability trials (60% trials)). RT did not differ as a function of win-probabilities for the LSA group in either positive or negative EV trials, or for the HSA group in the positive EV trials. In sum, the HSA group showed significantly slower RTs on trials that were likely to have the poorest outcomes (low win-probability in negative EV trials).

4. Discussion

The current study sought to extend a growing body of work on the relationship between social anxiety and risky behavior (Kashdan et al., 2008; Kashdan & McKnight, 2010; Muris, Luermans, et al., 2000a; Muris, Merckelbach, et al., 2000b; Muris et al., 2002; Reynolds et al., 2013) by exploring additional factors, including social context and reward parameters, that may modulate this relationship. To this end, a community sample of adolescents with varying levels of social anxiety performed a risky decision-making task in a Control condition and in a Social Stress condition. Percentage of bets (PC-bet) and reaction time (RT) on a risky decision-making task were used to measure risk-taking. Higher PC-bet and shorter RTs on trials presumably infer higher risk-taking propensity.

Based on existing literature, we hypothesized that high social anxiety (HSA) relative to low social anxiety (LSA) would be associated with more risk-averse behaviors (i.e., longer RTs and fewer bets) in the Control condition, but with more risk-prone behaviors (shorter RTs and higher PC-bets) following exposure to a Social Stress condition (Reynolds et al., 2013). Moreover, we hypothesized that these differential effects of social anxiety on risk-taking across two separate contexts would be further modulated by reward parameters, including the probability of receiving a reward and the magnitude of potential reward (expected value; EV). Findings revealed more subtle patterns of modulation of risk-taking behavior than hypothesized.

Overall, we found, as expected, that PC-bet was sensitive to the magnitude of rewards (reflected by EV) associated with each gamble (i.e., higher PC-bet to higher EV). Most importantly, the relationship between PC-bet and EV was modulated by individual social anxiety. HSA individuals showed enhanced sensitivity to EV compared to LSA. In other words, as EV moved from negative to positive, the HSA group increased its PC-bet more steeply than did the LSA group (see Figure 4). These data suggest that a study with a larger sample size and greater statistical power could reveal HSA individuals as more risk-averse in unfavorable conditions, and more risk-prone in favorable conditions relative to LSA individuals. This finding suggests that the likelihood of risk-taking in individuals with social anxiety is particularly sensitive to risk/benefit ratios, which are indexed here by EV measures. People with HSA may be risk-takers when these ratios are positive and risk-averse when they are negative.

This finding is in line with previous work on social anxiety, which has shown that behavioral responding to monetary reward is enhanced in individuals characterized as “shy” relative to their “non-shy” counterparts. These shy individuals are less effective at recruiting an approach-based behavioral response when there is a potential for punishment (Hardin et al., 2006). Moreover, there is growing evidence for a neural basis of increased reward sensitivity among anxious individuals. Specifically, neural circuitry involving the ventral striatum, a region frequently implicated in reward processing (Di Chiara, 2002), shows increased reactivity among anxious relative to non-anxious individuals when anticipating a reward (Guyer et al., 2012; Guyer et al., 2006). As such, the current findings provide additional evidence that highly anxious individuals are particularly sensitive to variations in risk/benefit ratios, and are more likely to make potentially risky decisions when there is a high potential for reward. In addition, and contrary to our predictions, group differences in risky decision-making were not modulated by the Social Stress condition, even though both groups reported increased negative affect in response to the Social Stress manipulation, suggesting that it was an effective stress induction method. In contrast to PC-bet, reaction times (RTs) across risky decision-making trials were influenced by the Social Stress condition. First, the LSA group was significantly faster at betting than at passing in the Control condition (i.e., greater propensity for risk-taking), but showed no RT differences between betting and passing in the Social Stress condition.

In contrast, the HSA group showed similar RTs in the Social Stress and Control condition, and for betting and passing responses. This finding may reflect two points. On the one hand, HSA individuals, in a low-stress control context, might not experience betting as more arousing (shorter RT) than passing, in contrast to LSA subjects. In fact, they seemed to show the same level of arousal not only across types of decision (Bet, Pass), but also across conditions (Social Stress, Control). On the other hand, social stress slowed down betting responses in the LSA group to a similar level as passing responses. Such slowed RT might reflect either the blunting of the excitement associated with taking a risk (reduced arousal), or a more conflictual betting response (taking a risk) in a negative stressful context. In contrast, HSA behaved in the control context as if they were in the stressful context, with similar RT to betting and passing. This may suggest that HSA individuals maintained a level of arousal and conflict of similar intensity in both the Control and the Social Stress context. This interpretation may be supported by the fact that on average across both experimental sessions, the HSA group showed an increase in negative affect regardless of condition (but the increase in negative affect was significantly stronger during the Social Stress session than Control), suggesting that even in a low-stress control condition, their alertness or arousal levels may have been elevated compared to the LSA group. This is reminiscent of the sustained tension and alertness that shy, inhibited individuals tend to exhibit, as indicated by elevated cortisol levels and heart rate at baseline (Calkins, Fox, & Marshall, 1996; Kagan, Reznick, & Snidman, 1987).

The second set of findings provided support for the differential influence of reward probability in LSA and HSA groups as a function of the value of the gamble (positive EV vs. negative EV). The HSA group showed sensitivity to the probability (40/60 vs. 60/40) on negative EV trials only. Namely, HSA individuals were slowest in response to the 40/60 trials when the EV was negative (Figure 7). The LSA participants showed no modulation of RT across EV or probability. This finding indicates that decision-making, whether it is passing or betting, was more difficult in the most negative type of trials for the HSA. The HSA group’s elevated sensitivity to the most negative trials supports the emotion bias theory of anxiety (Eysenck, Derakshan, Santos, & Calvo, 2007) by showing a dissociation of cognitive performance between anxious and non-anxious individuals as a function of valence. Specifically, our data suggest that decision-making becomes more difficult for anxious individuals in the most negative events (both low-win/high-loss probability and negative value).

The third set of findings concerned sensitivity to risk-taking as indexed by RT to passing or betting, particularly in response to the negative EV trials (Figure 6). Individuals with HSA were slower at betting than passing on negative EV trials, whereas those with LSA showed the opposite pattern. In fact, this latter pattern of longer RT to passing vs. betting seemed to be the norm in response to positive EV trials for both groups as well (Figure 6). Thus, the distinctly longer RTs when betting relative to passing for the HSA group in negative EV trials suggests that this group experienced betting as more difficult than passing, specifically in trials when the loss values were high (negative EV trials). This finding is consistent with the higher sensitivity of betting behavior (PC-bet, Figure 4) to EV within the HSA group relative to the LSA group, and with the unique sensitivity (longer RT) of the HSA group to the most negative trials (40/60 and negative EV) (Figure 7) as discussed above.

Collectively, these findings on RT, demonstrate that, regardless of the context (Social Stress vs. Control), HSA might be more sensitive to the reward parameters, especially the magnitude of expected reward values, evidencing significantly greater conflict (as evidenced by longer RTs) when making risky decisions in the context of more negative potential outcomes. In contrast, HSA and LSA seemed generally to behave similarly when generating a decision on trials that are most likely to yield positive outcomes.

A few limitations need to be addressed. First, the current work was conducted with a convenience sample of individuals from the community, few of whom actually evidenced clinical levels of social anxiety. This may be one of the reasons for the relatively weak effect of the Social Stress condition on betting behavior even though both groups showed a significant negative affective response to the stress manipulation. Second, the relatively small sample size limited our ability to examine other factors, such as gender, that could impact both negative affective responses to the social stress induction, and risky decision-making. Finally, our findings revealed only a relatively weak effect of Social Stress on risk-taking in HSA relative to LSA individuals, and this effect was found only on RT (no effect of Condition on PC-bets). Basically, this effect showed that HSA individuals behaved similarly during the Control condition and the Social Stress condition, in contrast to the LSA group whose RTs showed greater sensitivity to risk-taking (i.e., more discrepant RTs in response to betting vs passing), and an overall slowdown in the Social Stress condition relative to the Control condition. To better understand what might be driving this RT pattern across groups and conditions, future studies would need to collect data on arousal (e.g., skin conductance, heart rate) and cognitive control (e.g., Attention Control Scale (ACS); Derryberry & Reed, 2002), and perhaps use a different type of stressor to understand the role that social stress in particular may play, relative to other types of stress.

In conclusion, individuals with high social anxiety exhibited risk-taking behavior that was more sensitive to potential reward probability and magnitudes compared to individuals with low social anxiety. Moreover, HSA individuals evidenced more conflict when making risky decisions that were most likely to yield negative outcomes. We also showed that the HSA group evidenced similar decision-making times (RT) relative to the LSA group when experiencing a social stressor (anticipation of having to give a speech in front of judges). However, in a neutral situation, HSA subjects still behaved as if they were in a social stress situation, whereas LSAs showed a different pattern of risk-taking. This finding may reflect a sustained level of arousal and attentional control across contexts in HSA. Future work may benefit from extending the current study to clinical populations. For example, it would be important to examine individuals with clinical levels of social anxiety to see if the patterns observed here may be amplified when comparing adolescents with normative versus psychopathological levels of social anxiety. Although these behavioral findings were relatively modest overall, they may reflect significantly more powerful effects in the real world, and may be used to inform neural mechanisms of risky decision-making that are unique to a population suffering from social anxiety. The use of a similar research design in a functional neuroimaging environment may allow for the detection of differences in neural functioning between clinically anxious individuals and individuals with high but non-clinical levels of anxiety, relative to those with very little anxiety, even in the absence of behavioral differences (e.g., Guyer et al., 2012).

Research Highlights.

-

-

We tested effects of social anxiety, social stress and rewards on risk-taking

-

-

Reward value influenced risk-taking in those with high but not low social-anxiety

-

-

Social stress affected reaction time in those with low but not high social-anxiety

-

-

Those with high social anxiety evidenced greatest RT on the most negative trials

-

-

Effects of context and reward parameters depended on level of trait social anxiety

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Association, A.P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Beidel DC, Borden JW, Turner SM, Jacob RG. The Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory: concurrent validity with a clinic sample. Behav Res Ther. 1989;27(5):573–576. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(89)90093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidel DC, Turner SM. What are the adult consequences of childhood shyness? Harv Ment Health Lett. 1998;15(5):8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Eggleston AM, Schmidt NB. Social anxiety and problematic alcohol consumption: the mediating role of drinking motives and situations. Behav Ther. 2006;37(4):381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Fox NA, Marshall TR. Behavioral and physiological antecedents of inhibited and uninhibited behavior. Child Dev. 1996;67(2):523–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derryberry D, Reed MA. Anxiety-related attentional biases and their regulation by attentional control. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(2):225–236. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G. Nucleus accumbens shell and core dopamine: Differential role in behavior and addiction. Behav Brain Res. 2002;137(1–2):75–114. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00286-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Lodico M, Grinstead OA, Harper G, Rickman RL, Evans PE, Coates TJ. African-American adolescents residing in high-risk urban environments do use condoms: correlates and predictors of condom use among adolescents in public housing developments. Pediatrics. 1996;98(2 Pt 1):269–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M, Nelson EE, McClure EB, Monk CS, Munson S, Eshel N, Pine DS. Choice selection and reward anticipation: an fMRI study. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42(12):1585–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin BA, Heimberg RG, Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR. Anger experience and expression in social anxiety disorder: Pretreatment profile and predictors of attrition and response to cognitive-behavioral treatment. Behav Ther. 2003;34(3):331–350. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck MW, Derakshan N, Santos R, Calvo MG. Anxiety and cognitive performance: attentional control theory. Emotion. 2007;7(2):336–353. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Prospective childhood predictors of deviant peer affiliations in adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40(4):581–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullo MJ, Dawe S. Impulsivity and adolescent substance use: rashly dismissed as "all-bad"? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32(8):1507–1518. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer AE, Choate VR, Detloff A, Benson B, Nelson EE, Perez-Edgar K, Ernst M. Striatal functional alteration during incentive anticipation in pediatric anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(2):205–212. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer AE, Nelson EE, Perez-Edgar K, Hardin M, Roberson-Nay R, Monk CS, Ernst M. Striatal Functional Alteration in Adolescents Characterized by Early Childhood Behavioral Inhibition. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(24):6399–6405. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0666-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanby MS, Fales J, Nangle DW, Serwik AK, Hedrich UJ. Social anxiety as a predictor of dating aggression. J Interpers Violence. 2012;27(10):1867–1888. doi: 10.1177/0886260511431438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin MG, Perez-Edgar K, Guyer AE, Pine DS, Fox NA, Ernst M. Reward and punishment sensitivity in shy and non-shy adults: Relations between social and motivated behavior. Pers Individ Dif. 2006;40(4):699–711. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: changes from 1998 to 2001. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N. The physiology and psychology of behavioral inhibition in children. Child Dev. 1987;58(6):1459–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Elhai JD, Breen WE. Social anxiety and disinhibition: an analysis of curiosity and social rank appraisals, approach-avoidance conflicts, and disruptive risk-taking behavior. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(6):925–939. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Hofmann SG. The high-novelty-seeking, impulsive subtype of generalized social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(6):535–541. doi: 10.1002/da.20382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, McKnight PE. The darker side of social anxiety: When aggressive impulsivity prevails over shy inhibition. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2010;19(1):47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, McKnight PE, Richey JA, Hofmann SG. When social anxiety disorder coexists with risk-prone, approach behavior: investigating a neglected, meaningful subset of people in the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47(7):559–568. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Luermans J, Merckelbach H, Mayer B. "Danger is lurking everywhere". the relation between anxiety and threat perception abnormalities in normal children. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2000;31(2):123–136. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(00)00016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Merckelbach H, Damsma E. Threat perception bias in nonreferred, socially anxious children. J Clin Child Psychol. 2000;29(3):348–359. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2903_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Merckelbach H, Walczak S. Aggression and threat perception abnormalities in children with learning and behavior problems. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2002;33(2):147–163. doi: 10.1023/a:1020782208977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers MG, Aarons GA, Tomlinson K, Stein MB. Social anxiety, negative affectivity, and substance use among high school students. Psychol Addict Behav. 2003;17(4):277–283. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds EK, Schreiber WM, Geisel K, MacPherson L, Ernst M, Lejuez CW. Influence of social stress on risk-taking behavior in adolescents. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27(3):272–277. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson-Nay R, Strong DR, Nay WT, Beidel DC, Turner SM. Development of an abbreviated Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory (SPAI) using item response theory: the SPAI-23. Psychol Assess. 2007;19(1):133–145. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounds JS, Beck JG, Grant DM. Is the delay discounting paradigm useful in understanding social anxiety? Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(4):729–735. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy AK, Gotimer K, Kelly AM, Castellanos FX, Milham MP, Ernst M. Uncovering putative neural markers of risk avoidance. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(5):937–944. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneier FR, Foose TE, Hasin DS, Heimberg RG, Liu SM, Grant BF, Blanco C. Social anxiety disorder and alcohol use disorder co-morbidity in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2010;40(6):977–988. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schry AR, Roberson-Nay R, White SW. Measuring social anxiety in college students: a comprehensive evaluation of the psychometric properties of the SPAI-23. Psychol Assess. 2012;24(4):846–854. doi: 10.1037/a0027398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Spear LP, Fuligni AJ, Angold A, Brown JD, Pine D, Dahl RE. Transitions into underage and problem drinking: developmental processes and mechanisms between 10 and 15 years of age. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl 4):S273–S289. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]