Abstract

Rationale: Sirolimus therapy stabilizes lung function and reduces the size of chylous effusions and lymphangioleiomyomas in patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

Objectives: To determine whether sirolimus has beneficial effects on lung function, cystic areas, and adjacent lung parenchyma; whether these effects are sustained; and whether sirolimus is well tolerated by patients.

Methods: Lung function decline over time, lung volume occupied by cysts (cyst score), and lung tissue texture in the vicinity of the cysts were quantified with a computer-aided diagnosis system in 38 patients. Then we compared cyst scores from the last study on sirolimus with studies done on sirolimus therapy. In 12 patients, we evaluated rates of change in lung function and cyst scores off and on sirolimus.

Measurements and Main Results: Sirolimus reduced yearly declines in FEV1 (−2.3 ± 0.1 vs. 1.0 ± 0.3% predicted; P < 0.001) and diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide (−2.6 ± 0.1 vs. 0.9 ± 0.2% predicted; P < 0.001). Cyst scores 1.2 ± 0.8 years (30.5 ± 11.9%) and 2.5 ± 2 years (29.7 ± 12.1%) after initiating sirolimus were not significantly different from pretreatment values (28.4 ± 12.5%). In 12 patients followed for 5 years, a significant reduction in rates of yearly decline in FEV1 (−1.4 ± 0.2 vs. 0.3 ± 0.4% predicted; P = 0.025) was observed. Analyses of 104 computed tomography scans showed a nonsignificant (P = 0.23) reduction in yearly rates of change of cyst scores (1.8 ± 0.2 vs. 0.3 ± 0.3%; P = 0.23) and lung texture features. Despite adverse events, most patients were able to continue sirolimus therapy.

Conclusions: Sirolimus therapy slowed down lung function decline and increase in cystic lesions. Most patients were able to tolerate sirolimus therapy.

Keywords: sirolimus, lung cystic destruction, LAM

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Treatment of lymphangioleiomyomatosis with sirolimus decreases the rate of decline in lung function and improves quality of life. Sirolimus is also effective in reducing the size of lymphangioleiomyomas and chylous effusions. However, there are no data regarding effects of sirolimus on lung volume occupied by cysts and degradation of lung parenchyma in the vicinity of cysts, leading to cyst formation.

What This Study Adds to the Field

We found that sirolimus is effective in reducing the rate of decline in lung function and slowing down changes in lung volume occupied by cysts, while reducing changes in tissue texture in nearby noncystic areas. These effects of sirolimus seem to be sustained over a period of 5 years. Adverse events associated with sirolimus were generally well tolerated.

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a multisystem disease affecting almost exclusively women, which is characterized by cystic lung destruction, renal angiomyolipomas, and lymphangioleiomyomas (1–4). Patients with LAM frequently present with dyspnea on exertion; recurrent pneumothoraces; chylous effusions; incidental detection of lung cysts on imaging studies; and, less frequently, bleeding angiomyolipomas (1, 2). The clinical course of LAM is variable but LAM is generally considered to be a chronic disease with a median transplant-free survival time spanning more than a decade (5). LAM lesions are characterized by proliferation of a neoplastic LAM cell, which has features both of smooth muscle and melanocytic cells (4). The histologic features of LAM consist of cysts and LAM cells in the walls of cysts and along blood vessels, lymphatics, and bronchioles, causing airways narrowing, vascular wall thickening, lymphatic disruption, and venous occlusion (4).

The inherited form of LAM associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is caused by mutations in the TSC1 or TSC2 suppressor genes (6–8). Sporadic LAM has been associated only with mutations of TSC2 (6–8). TSC1 and TSC2 encode, respectively, hamartin and tuberin, two proteins acting upstream from the intracellular serine/threonine kinase mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), which is important in regulating cell proliferation and size (9–12).

Sirolimus and everolimus, two immunosuppressant compounds that inhibit mTOR (12–14), are effective in decreasing the size of renal angiomyolipomas in patients with TSC or LAM (15–17), and reducing the size of giant cell astrocytomas and the severity of skin angiofibromas in patients with TSC (18–20). Treatment with sirolimus for 1 year decreased the rates of decline in FVC and FEV1 and improved quality of life (21). Sirolimus was also found to reduce the size of lymphangioleiomyomas and chylous effusions (22), and lead to resolution of pulmonary infiltrates (22, 23).

Reduction in the size of lung nodules and LAM cell infiltrates involving or surrounding the airways is thought to account for the stabilization or improvement in lung function associated with sirolimus therapy. However, there are no data regarding reduction or stabilization of cyst volume and degradation of lung parenchyma, leading to cyst formation. For several years, we have been following a cohort of patients with LAM who are being treated with sirolimus. Over time of follow-up, high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scans, pulmonary function tests, 6-minute-walk test (6MWT), and cardiopulmonary exercise tests have been obtained.

We have developed a new technique that measures changes in the percentage of lung volume occupied by cysts (cyst score) and changes in lung tissue properties (e.g., texture) in areas surrounding the cystic lesions (24) that is correlated with changes in lung function (24). The aims of this study were to determine whether the effects of sirolimus are associated with reduction of lung function decline, stabilization of lung cystic lesions, and surrounding lung parenchyma; to determine whether the effects of sirolimus are sustained; and to assess the frequency and severity of adverse events associated with its use. Data from 13 of the 38 patients hereby reported were the subject of a previous report (22).

Methods

Patient Population

The subjects of this study were self-referred or referred by their physicians to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for participation in a LAM natural history and pathogenesis protocol (NHLBI Protocol 95-H-0186), which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the NHLBI. Subjects were also informed of the studies by the LAM Foundation and the Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance. All subjects gave written informed consent before enrollment. Sirolimus was prescribed by the patients’ physicians, with whom we maintained close contact. Drug dosage was adjusted based on MILES study recommendations (21). Patients were seen every 6 months at the NIH Clinical Center. Clinical and functional data, including history and physical examination, laboratory tests, pulmonary function tests, and cardiopulmonary exercise testing, were obtained at the time of each visit. HRCT scans of the thorax and abdomen were performed every year or 2 years or when medically indicated.

Pulmonary Function Testing

Lung volumes, flow rates, and diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide (DlCO) were measured using a Master Screen PFT (Erich Jaeger, Wuerzburg, Germany) system according to American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society standards (25, 26). Rates of change in lung function per year were estimated as previously reported (22, 27).

Radiologic Methods

HRCT scans of the lungs (GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI; Phillips Healthcare, Amsterdam, Netherlands; and Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) were performed with the patients in a prone position during end inspiration at 120–140 kilovolt peak and 118–560 mA, with 1- to 2-second scanning times and 34- to 38-cm field of view (24). The scans contained 9–13 slices and the slice thickness ranged from 1 to 1.25 mm at 3-cm intervals. The image was reconstructed in the computed tomography scanner using lung kernel (filter) to emphasize the range of image pixel values for lung tissues. Then, by means of a computer-aided diagnostic system, the lungs were segmented and a histogram-based technique was used to exclude large blood vessels. A threshold of −700 HU was used initially to define the cystic regions (24). After cystic regions were outlined, texture features in the vicinity of the cysts and in lung regions at least 10 mm away from any cystic regions were analyzed.

The image was subdivided into blocks for texture computation. Twenty-five different texture features, including mean and variance features from histogram statistics, energy and entropy features from cooccurrence matrix, and short- and long-run emphasis features from run-length matrix, were calculated. Among texture features, entropy represents a measure of spatial disorder (24). A completely random distribution would have very high entropy. A uniform distribution would be reflected by low entropy. Energy is a measure of local homogeneity, which describes the uniformity of the density distribution. A wide energy distribution would correspond to a mixture of cysts and normal lung parenchyma. Conversely, a narrow energy distribution would be observed either in the setting of predominantly normal lung or a cystic pattern. For each lung HRCT scan, the percent of total lung volume occupied by cystic lesions (cyst score), and energy and entropy features were computed (24).

Six-Minute-Walk Tests

Tests were performed using standard protocols (28). Patients were instructed to walk as fast as possible for 6 minutes, while being encouraged using set phrases every 30 seconds. Some patients walked while receiving supplemental oxygen.

Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing

Patients exercised on a bicycle ergometer and a computerized metabolic cart (Vmax 229 Cardiopulmonary Exercise System; Sensormedics, Yorba Linda, CA) using standard incremental protocols (29).

Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

Multiple pulmonary function measurements for each of the patients were available for analysis. The information from each subject was summarized by using the estimated yearly rate of change (slope), calculated from a linear regression for pulmonary function data (27). An adjusted analysis was performed using mixed effects models. A time-dependent group indicator and adjustment for baseline lung function tests were used in all models. Both unadjusted and adjusted analyses account for intrapatient correlation.

Cyst scores and texture features obtained before starting sirolimus therapy were compared with those derived from the first HRCT scan after initiation of therapy and the last, most recent, HRCT scan, by means of analysis of variance for serial observations using the Tukey-Kramer procedure. In 12 patients in whom 104 HRCT scans were available for analysis, we compared pretherapy and post-therapy rates of change using mixed effects models adjusting for baseline measurements. Rates of cyst scores and lung function changes are expressed as means (± SEM), a more precise estimate of the variability; it takes into consideration the number of observations, which is a function of the number of subjects, and the number of visits for each of the subjects.

Results

Patients Characteristics

Demographic features, including age of diagnosis and age of first symptoms of the 38 patients treated with sirolimus, are shown in Table 1. Five patients had tuberous sclerosis. Most patients were diagnosed by tissue biopsy. The most frequent presenting symptoms were dyspnea (50%) and pneumothorax (42%). Seventy-three percent of the patients were receiving supplemental oxygen. No patient died or proceeded to lung transplantation during the study.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Data of 38 Patients with LAM

| Demographics | |

| White | 35 |

| Black | 1 |

| Asian | 2 |

| Age of diagnosis, yr | 38.4 ± 9.8 |

| Age, first symptoms, yr | 35.5 ± 8.9 |

| Age, first NIH visit, yr | 40.9 ± 9.5 |

| TSC | 5 (13%) |

| Oxygen therapy | 28 (73%) |

| Deaths during study | None |

| Lung transplantation | None |

| Initial symptoms | |

| Dyspnea | 19 (50%) |

| Pneumothorax | 16 (42%) |

| Hemoptysis | 3 (8%) |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (10%) |

| No respiratory symptoms | 1 (2%) |

| Extrapulmonary findings | |

| Lymphangioleiomyomas | 17 (45%) |

| Angioyolipomas | 17 (45%) |

| Mode of diagnosis of LAM | |

| Open lung biopsy | 17 (44%) |

| Transbronchial lung biopsy | 3 (8%) |

| Abdominopelvic mass biopsy | 3 (8%) |

| Biopsy of angiomyolipoma | 1 (2%) |

| Chylous effusions | 5 (13%) |

| Lymphangioleiomyomas | 4 (10%) |

| Lung cysts on CT scan and VEGF-D values greater than 0.8 ng/ml | 4 (10%) |

| Lung cysts on CT scan and TSC or angiomyolipomas | 6 (15%) |

Definition of abbreviations: CT = computed tomography; NIH = National Institutes of Health; LAM = lymphangioleiomyomatosis; TSC = tuberous sclerosis complex; VEGF-D = vascular endothelial growth factor D.

Adverse Events Associated with Sirolimus Therapy

The mean dose of sirolimus was 2.4 ± 0.8 mg/day; the average serum sirolimus level was 8.0 ± 2.5 ng/ml. Adverse events referring to any occurrence of any event during the time of observation are listed in Table 2. Because most patients were seen every 6 months multiple observations were made during an average of 3.4 ± 2.4 years. The most frequent adverse reactions were hypercholesterolemia (68%), upper respiratory tract infections (66%), stomatitis (58%), diarrhea (55%), peripheral edema (53%), acne (50%), hypertension (34%), headaches (40%), leukopenia (40%), delayed wound healing (26%), thrombocytopenia (21%), and proteinuria (21%). Neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were generally mild (Table 2). No patient had neutrophil counts less than 1,000 or platelet counts under 100,000. Urine protein/creatinine ratios were frequently increased during sirolimus therapy (Table 2). Treatment of hypercholesterolemia, worsening or new-onset hypertension, and close monitoring of renal function, especially urine protein/creatinine ratio, were undertaken.

Table 2.

Adverse Events Occurring During Sirolimus Therapy in 38 Patients with Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

| Number of patients | 38 |

| Endocrine/metabolic | |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 26 (68.4%) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 193.8 ± 29.7 (116–278) |

| Mean low-density lipoprotein | 115.5 ± 29.9 (62–196) |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 13 (34.2%) |

| Elevated glucose | 3 (7.9%) |

| Increased HgbA1C | 3 (7.9%) |

| Gastrointestinal | |

| Abdominal pain | 7 (18.4%) |

| Constipation | 7 (18.4%) |

| Diarrhea | 21 (55.3%) |

| Nausea | 4 (10.5%) |

| Stomatitis | 22 (57.9%) |

| Vomiting | 2 (5.3%) |

| Gastritis | 4 (10.5%) |

| Increased liver enzymes | 7 (18.4%) |

| Dermatologic | |

| Acne | 19 (50%) |

| Rash | 10 (26.3%) |

| Delayed wound healing | 10 (26.3%) |

| Skin infection | 4 (10.5%) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1 (2.6%) |

| Hematologic | |

| Anemia | 2 (5.3%) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 8 (21.1%) |

| Neutropenia/leukopenia | 15 (39.5%) |

| White cell count, thousands/μl | 5.1 ± 1.5 (2–10. 2) |

| Neutrophil count, thousands/μl | 3.1 ± 1.3 (1–7. 6) |

| Lymphocyte count, thousands/μl | 1.4 ± 0.5 (0.4–3.1) |

| Platelet count, thousands/μl | 244.0 ± 61.7 (121.0–445.0) |

| Musculoskeletal | |

| Arthralgia | 9 (23.7%) |

| Myopathy | 4 (10.5%) |

| Neurologic | |

| Headache | 15 (39.5%) |

| Confusion | 0 |

| Memory impairment | 0 |

| Tremor | 5 (13.2%) |

| Renal | |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 0.79 ± 0.17 (0.38–1.45) |

| Elevated creatinine | 4 (10.5%) |

| Urinary tract infection | 7 (18.4%) |

| Urine protein/creatinine ratio | 0.124 ± 0.075 (0.026–0.33) |

| Proteinuria | 8 (21.1%) |

| Respiratory | |

| Epistaxis | 2 (5.3%) |

| Upper respiratory infection | 25 (65.8%) |

| Cardiovascular | |

| Peripheral edema | 20 (52.6%) |

| Hypertension | 13 (34.2%) |

| Other | |

| Fever | 1 (2.6%) |

| Pain (other) | 15 (39.5%) |

| Cancer | 1 (2.6%) |

| Weakness | 3 (7.9%) |

One additional patient after taking six doses of sirolimus developed chest tightness and dyspnea, requiring hospitalization. A chest radiograph showed no pulmonary infiltrates; sirolimus was discontinued. Fourteen months later, under close observation at the NIH Clinical Center, the patient was restarted on sirolimus. After 7 days of therapy without untoward effects, she was discharged. Several days later, however, she called and said that she was experiencing chest tightness and dyspnea and the drug was discontinued. Physiologic or radiologic data were not obtained during sirolimus therapy. Because the occurrence of drug intolerance could not be verified, the patient was excluded from this report.

Rates of Change in Lung Function

Pulmonary function tests done at the time of the first NIH visit showed decreased FEV1, FEV1/FVC ratio, and DlCO (Table 3). In 38 patients followed for 3.4 ± 2.0 years the rates of change in FEV1 before (7.2 ± 5.1 yr) and during treatment with sirolimus expressed as means (± SEM) were, respectively, −2.2 ± 0.1% predicted (−79 ± 3 ml) and 1.0 ± 0.3% predicted (25 ± 8 ml) per year (P < 0.001) (Table 4). Yearly changes in DlCO before and during sirolimus therapy were −2.6 ± 0.1% predicted (−0.61 ± 0.02 ml/min/mm Hg) and 0.9 ± 0.2% predicted (0.22 ± 0.05 ml/min/mm Hg), respectively (P < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Pulmonary Function of 38 Patients with Lymphangioleiomyomatosis at the Time of the First National Institutes of Health Visit

| TLC, L | 5.1 ± 0.8 |

| TLC, % predicted | 97.6 ± 16.6 |

| FRC, L | 3.0 ± 0.6 |

| FRC, % predicted | 103.4 ± 21.9 |

| RV, L | 1.9 ± 0.5 |

| RV, % predicted | 110.7 ± 29.8 |

| FVC, L | 3.3 ± 0.6 |

| FVC, % predicted | 91.1 ± 17.6 |

| FEV1, L | 2.0 ± 0.7 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 72.1 ± 22.7 |

| DlCO, ml/min/mm Hg | 13.6 ± 5.4 |

| DlCO, % predicted | 62.5 ± 23.8 |

Definition of abbreviations: DlCO = diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide; RV = residual volume.

Table 4.

Yearly Changes in Lung Function before and after Treatment with Sirolimus in 38 Patients with Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

| Before Sirolimus Began | After Sirolimus Began | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean time, yr | −7.2 ± 5.1 | 3.4 ± 2.0 |

| Change in % predicted FVC | −0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.2* |

| Change in FVC, ml | −35 ± 4 | 23 ± 10† |

| Change in % predicted FEV1 | −2.2 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.3† |

| Change in FEV1, ml | −79 ± 3 | 25 ± 8† |

| Change in % predicted DlCO | −2.6 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.2† |

| Change in DlCO , ml/min/mm Hg | −0.61 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.05† |

Definition of abbreviation: DlCO = diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide.

P = 0.015.

P < 0.001.

Changes in Cyst Scores and Lung Texture Features

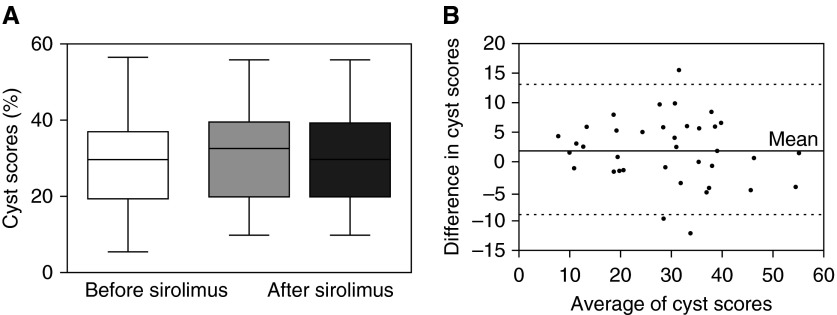

Cyst scores derived from HRCT studies done an average of 1.2 ± 0.8 years after beginning treatment (30.1 ± 11.9%) and the last scan obtained 2.5 ± 2.0 years after starting treatment with sirolimus (29.7 ± 12.1%) were not significantly different (analysis of variance) from the cyst scores measured on the last HRCT scan performed 1.4 ± 1.3 years before treatment was begun (28.4 ± 12.5) (Figure 1A). Furthermore, no significant changes were observed in texture features around the cystic areas (Table 5). Figure 1B shows a Bland-Altman plot indicating that there is agreement between pretherapy and post-therapy cyst scores. Overall, post-treatment cyst scores remained largely unchanged from those observed before treatment with sirolimus.

Figure 1.

Lung cyst scores before and after treatment with sirolimus in 38 patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis. (A) Box and whiskers plot showing cyst scores for the last high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan taken 1.4 ± 1.3 years before beginning treatment with sirolimus (white box), the first HRCT scan taken 1.2 ± 0.8 years after beginning the treatment (light gray box), and the last HRCT scan taken 2.5 ± 2.0 years after starting treatment (dark gray box). The bottom line of each box represents the first quartile, the top line represents the third quartile, and the line across the boxes represents the second quartile (median). The upper and lower whiskers indicate the maximum and minimum cyst score values. There were no statistically significant differences in cyst scores between pretreatment and post-treatment studies. (B) Bland-Altman plot of the difference between each pair of pre-sirolimus and post-sirolimus therapy cyst scores and average of each pair of cyst scores. The top and bottom dotted lines represent the 95% confidence level.

Table 5.

Cyst Scores and Lung Texture Features before and after Treatment with Sirolimus in 38 Patients with Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

| Last Study before Sirolimus Began | First Study after Sirolimus Began | Last Study Done on Sirolimus | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean time, yr | −1.4 ± 1.3 | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 2.5 ± 2.0 |

| Cyst score, % | 28.4 ± 12.5 | 30.1 ± 11.9 | 29.7 ± 12.1* |

| Change in difference in entropy around cysts | −110.0 ± 22.7 | −114.7 ± 21.7 | −115.3 ± 20.9† |

| Change in difference in energy around cysts | 4.0 ± 1.6 | 4.3 ± 1.5 | 4.3 ± 1.4‡ |

P = 0.82.

P = 0.52.

P = 0.65.

6MWTs

Twenty-five patients had 6MWT before starting therapy with sirolimus and again 3.4 ± 1.9 years later (Table 6). A slight increase in the distance walked and a slightly higher resting and peak exercise SaO2 were observed after treatment with sirolimus. There was, however, an increase in the amount of supplemental oxygen used during exercise. Except for the initial SaO2 before exercise, none of these differences were statistically significant.

Table 6.

Six-Minute-Walk Test before and after Treatment with Sirolimus in 25 Patients with Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

| Before Sirolimus Began | After Sirolimus Began | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean time, yr | −0.5 ± 0.4 | 3.4 ± 1.9 | |

| Distance, m | 373 ± 109 | 412 ± 85 | 0.164 |

| Initial heart rate, beats/min | 90 ± 12 | 88 ± 12 | 0.551 |

| Final heart rate, beats/min | 115 ± 17 | 122 ± 15 | 0.129 |

| Initial SaO2, % | 97 ± 2 | 99 ± 1 | <0.001 |

| Final SaO2, % | 87 ± 7 | 89 ± 5 | 0.251 |

| Oxygen, L/min | 3.5 ± 3.5 | 4.2 ± 2.8 | 0.430 |

Cardiopulmonary Exercise Tests

The results of cardiopulmonary exercise tests performed before treatment with sirolimus and 2.8 ± 1.7 years after treatment was begun are shown in Table 7. There was no evidence of decline in exercise performance. There was a trend for increased Vo2max and breathing reserve, lower VE/Vco2, and a lesser drop in SaO2 at peak exercise, but these differences were not statistically significant.

Table 7.

Exercise Physiology before and after Treatment with Sirolimus in 11 Patients with Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

| Before Sirolimus | After Sirolimus | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean time, yr | −0.5 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 1.7 | |

| Work rate, % | 86 ± 17 | 90.7 ± 30.5 | 0.610 |

| HR max, beats/min | 152 ± 17 | 152 ± 27 | 0.990 |

| HR max, % | 87 ± 9 | 89 ± 15 | 0.770 |

| VO2max, ml/min | 1,217 ± 276 | 1,219 ± 305 | 0.990 |

| VO2max, % | 74 ± 15 | 78 ± 20 | 0.390 |

| VO2/HR max, ml/beat | 8 ± 2 | 8 ± 2 | 0.970 |

| VO2/HR max, % | 82 ± 13 | 79 ± 13 | 0.591 |

| VE max, L/m | 50 ± 12 | 49 ± 12 | 0.841 |

| VE max, % | 62 ± 15 | 55 ± 13 | 0.251 |

| BR, % | 26 ± 18 | 31 ± 17 | 0.510 |

| VE/Vco2 AT | 37 ± 6 | 34 ± 5 | 0.210 |

| Resting SaO2, % | 97 ± 2 | 97 ± 2 | 0.990 |

| Peak exercise SaO2, % | 91 ± 4 | 93 ± 4 | 0.250 |

| Decline in SaO2, % | 6 ± 3 | 4 ± 3 | 0.131 |

Definition of abbreviations: BR = breathing reserve; HR = heart rate; VE max = minute ventilation at peak exercise; VE/Vco2 AT = ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide at anaerobic threshold; VO2 max/HR = oxygen pulse.

Data are shown as mean ± SD.

Long-Term Effect of Sirolimus on Lung Function, Cyst Scores, and Lung Texture Features

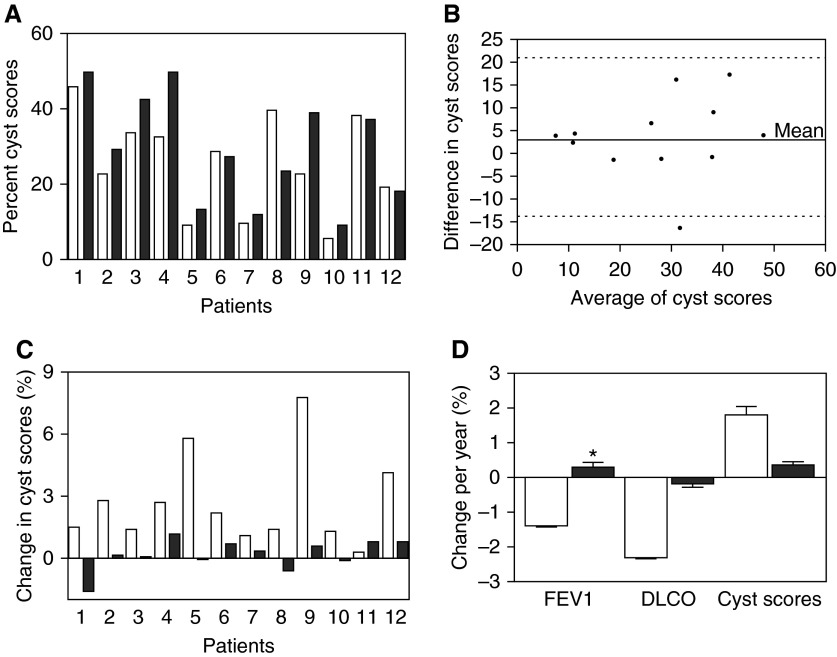

Changes in FEV1 and DlCO before and after therapy were, respectively, −1.4 ± 0.2% predicted (−55 ± 7 ml) and 0.3 ± 0.4% predicted (−5 ± 12 ml) per year (P = 0.025). Yearly changes in DlCO before (−2.3 ± 0.2% predicted) and after (−0.1 ± 0.3% predicted) therapy were not significantly different (Figure 2D, Table 8).

Figure 2.

Changes in cyst scores before and after treatment with sirolimus in 12 patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis followed for an average of 5.2 ± 1.7 years. (A) Cyst scores before (white bars) and after (black bars) treatment are shown for each patient. (B) Bland-Altman plot of the difference between each pair of presirolimus and post-sirolimus therapy cyst scores and average of each pair of cyst scores. The top and bottom dotted lines represent the 95% confidence level. (C) Rate of change in cyst scores before (white bars) and after (black bars) treatment with sirolimus for each of the 12 patients. All but one patient experienced a decrease in the rate of change of cyst scores. (D) Adjusted yearly rates of change in cyst scores, FEV1, and diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide (DlCO). Although the rates of cyst scores decreased during treatment with sirolimus the small sample size made it difficult to show statically significant results. The same was true of DlCO rates of change. However, there was a statistically significant reduction in rates of change of FEV1. *P = 0.025.

Table 8.

Mixed Effects Analysis of Yearly Changes in Lung Function, Cyst Scores, and Lung Texture Features before and during Treatment with Sirolimus in 12 Patients with Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

| Before Sirolimus | After Sirolimus | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean lung function time, yr | −6.4 ± 4.9 | 5.2 ± 1.7 |

| Change in % predicted FEV1 | −1.4 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.4* |

| Change in FEV1, ml | −55 ± 7 | −5 ± 12* |

| Change in % predicted DlCO | −2.3 ± 0.2 | −0.1 ± 0.3 |

| Change in DlCO, ml/min/mm Hg | −0.53 ± 0.04 | 0.05 ± 0.7 |

| Mean HRCT scan time, yr | −5.5 ± 3.2 | 4.6 ± 1.8 |

| Change in cyst score | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.3 |

| Change in entropy around cysts | 1.49 ± 0.5 | −0.97 ± 0.75 |

| Change in energy around cysts | −0.06 ± 0.04 | 0.1 ± 0.06 |

Definition of abbreviations: DlCO = diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide; HRCT = high-resolution computed tomography.

P = 0.025.

A total of 104 HRCT scans (mean, 8.6 ± 2.7) from 12 patients who had at least two studies before and at least two studies after treatment with sirolimus were examined. Before therapy patients were followed for an average of 5.5 ± 3.3 years. Follow-up time during sirolimus therapy was 4.6 ± 1.8 years. Changes in cyst scores and changes in texture features in areas in the vicinity of the cysts for each patient before (white bars) and after (black bars) treatment are shown in Table 8 and Figure 2. Figure 2B shows a Bland-Altman plot indicating that there was agreement between pretherapy and post-therapy cyst score values. Data indicate that during treatment with sirolimus cyst scores remained mostly unchanged.

The rates of change in cyst scores before (white bars) and after (black bars) treatment with sirolimus for each of the 12 patients are shown in Table 8 and Figure 2C. All but one patient had a reduction in rates of change in cyst scores. A mixed models analysis done to incorporate the within and between subject variability and the repeated measurements showed that presirolimus rate of change in cyst scores (1.8 ± 0.2% per yr) (Figure 2D) was greater than, but not statistically significantly different (P = 0.23) from, the rate of change in cyst scores during therapy (0.3 ± 0.3% per yr) (Table 8). The same was true for the rates of change in entropy and energy around the cysts (P = 0.129) (Table 8). The lack of statistical significance is likely caused by the small sample size and lack of power to detect a significant difference at the observed levels.

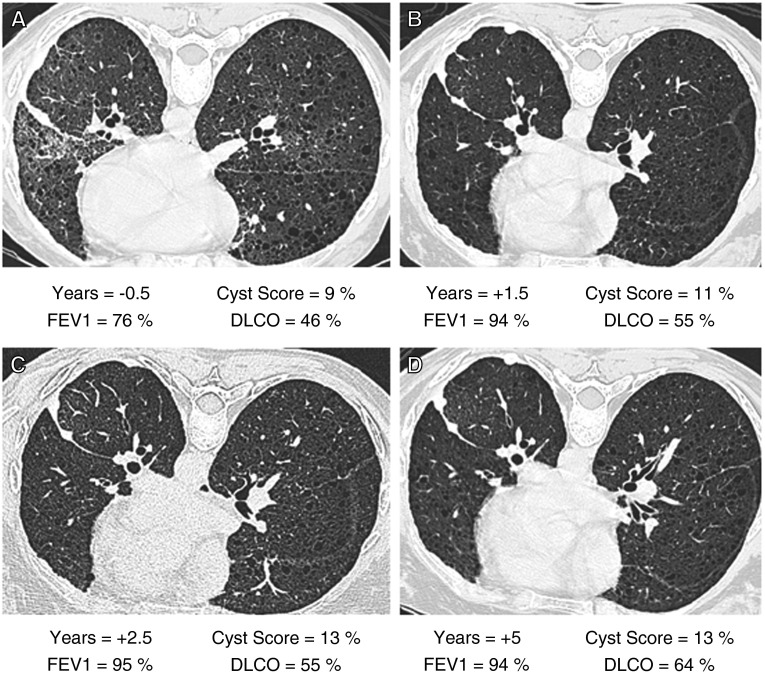

Figure 3 shows HRCT scans, cyst scores, FEV1, and DlCO of one patient who had undergone a left pleurodesis for treatment of a chylous effusion who was followed for 5 years. The figure shows that lung function improved initially, presumably because of clearing of the pleural effusion and pulmonary infiltrates, and then stabilized. During the last 3.5 years of sirolimus therapy cyst scores remained unchanged.

Figure 3.

High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scans, cyst scores, FEV1, and diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide (DlCO) before and during 5 years of therapy with sirolimus. The patient had undergone a pleurodesis for treatment of a left chylous effusion before starting treatment with sirolimus. For each panel, years before or after initiation of treatment, percent cyst score, percent-predicted FEV1, and DlCO are indicated. (A) HRCT scan and pulmonary function tests were performed 1.5 years before starting sirolimus. There is evidence of cystic lung disease, interstitial infiltrates, and fluid collection in the left major lung fissure. Cyst score was 9%. (B) Studies done 1.5 years after starting sirolimus therapy show a cyst score of 11% and improvement in lung function, presumably because of resolution of residual pleural effusion and lung infiltrates. (C) Studies done 2.5 years after beginning therapy show a cyst score of 13% and stable FEV1 and DlCO. (D) Studies done after 5 years of therapy show that cyst score still is 13%, and FEV1 and DlCO are unchanged since the previous study.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was threefold: (1) to examine the effect of long-term sirolimus therapy on lung function and CT features, (2) to determine whether treatment with sirolimus stabilized the volume of lung cystic areas and emphysematous-like lesions that may appear around and between the cysts (24), and (3) to assess rates and severity of adverse events associated with long-term sirolimus therapy. Because the MILES trial had shown that the sirolimus group had improvement from baseline to 12 months in lung function, quality of life, and functional performance (21), it was important to determine if these beneficial effects of sirolimus were sustained beyond 1 year of treatment. Furthermore, patients previously reported to have sustained benefit from sirolimus beyond 2 years of therapy (22) had lymphangioleiomyomas, chylous effusions, ascites, and perhaps pulmonary infiltrates, which on undergoing resolution following sirolimus therapy had an effect on the improvement in lung function (22, 23).

Our study shows that treatment with sirolimus for a period of about 3.5 years stabilized lung function by slowing declines in FEV1 and DlCO and changes in lung volume occupied by cysts. The 6MWT and cardiopulmonary exercise tests findings are consistent with this stabilization of lung function, because both these tests showed no evidence of worsening in exercise tolerance or reduced exercise capacity. In the case of the 6MWT, however, the oxygen requirements increased but the distance walked also increased while oxygen saturation at rest and at peak exercise were higher.

In a subgroup of patients followed for approximately 5 years, we demonstrated both a reduction in functional decline and changes in cyst scores and lung tissue texture features around cystic lesions. These data suggest that the volume of preexisting cysts increased less during the duration of sirolimus therapy, and lung tissue areas near previously existing cysts stabilized. We hypothesize that during sirolimus therapy LAM cells surrounding the airways decrease in size, and airflow obstruction is reduced. This could lead either to no change or a reduction in the volume of the cysts. We suggest that during sirolimus therapy, improved air entry into airspaces upstream from less obstructed airways should not lead to more air trapping and, consequently, an increase in cyst volume. Instead, if the cysts are communicating with airways, we would expect the cysts to decrease in volume. However, from our data, it seems that during sirolimus therapy the volume of the cysts changed only at a lesser rate. Finally, we found that the therapeutic effects of sirolimus were sustained over 5 years and although the prevalence of adverse events associated with sirolimus therapy was high and broad, most patients were able to continue therapy with only brief interruptions.

One criticism of this study is that the prevalence of lymphatic involvement in our cohort is too high and is not representative of a LAM population. Moreover, resolution of chylous effusions or lung infiltrates could invalidate measurements of functional decline or changes in cyst scores. It should be noted, however, that one of the indications for sirolimus therapy is lymphatic disease, namely symptomatic pleural effusions, ascites, and abdominal lymphangioleiomyomas. Accordingly, we maintain that our population is representative of patients who are most likely to receive treatment with mTOR inhibitors. Regarding CT scan data, we made all efforts to exclude patients with pulmonary infiltrates or large effusions that could preclude the computer analysis. That is, HRCT scan data were derived from analysis of studies that were suitable for cyst detection. The assessment of lung cyst volume and texture features was performed by the first author, who developed the technique (24), and was masked as to patients’ lung function and demographic data. On review of all the CT scans, we found that 17 patients had lymphangioleiomyomas, seven had pleural effusions, and three had ascites (see Table E1 in the online supplement). Only one patient had evidence of pulmonary infiltrates that resolved after initiation of sirolimus therapy (Figure 3). The patients with large pleural effusions resolving on sirolimus that were previously reported (22) were not part of this study.

The HRCT computer analysis technique that we used is able to differentiate between fibrotic and nonfibrotic areas, and honeycombing, ground glass, nodular, and emphysema-like lesions (24, 30). The rationale for examining changes in LAM lung tissue in areas near the cystic lesions is based on evidence that texture changes in these areas, as determined by computer-based analysis of HRCT scans, are associated with “emphysematous-like” changes in the lung parenchyma documented by histopathology (24). Histopathologic studies showed emphysema-like tissue changes that were compatible with the HRCT data. These texture changes, which were not seen in the normal lung, could reflect degradation of lung parenchyma in areas in the vicinity of the cysts (24). In a prior study using this technique, we showed that cyst scores correlate with FEV1, whereas sum entropy, a texture feature, in the vicinity of the cysts correlated with DlCO. Our first specific aim of the current study was precisely to determine whether treatment with sirolimus would decrease the size (e.g., volume) of the cysts and reduce the formation of emphysematous-like lesions that may occur between cysts and that have been shown to be detectable by computer analysis of HRCT (24). Our findings, however, should be interpreted with caution. Indeed, the texture analysis, which evaluates the appearance of pulmonary tissues on HRCT scans, measures the combined effect of emphysematous changes and LAM cell infiltration.

The mechanism by which LAM cell proliferation causes the formation of cysts is poorly understood (31). One hypothesis is that proliferation of LAM cells obstructs the airways causing distention of alveolar units upstream from these airways (4, 32). More likely, cystic lesions result from actual destruction of the lung parenchyma. Our study suggests that during sirolimus therapy, these cystic lung lesions and texture features around the cysts ceased to progress or progressed at a lesser rate. This could be caused by a reduction in LAM cells size and number, which would decrease destruction of the lung parenchyma. Indeed, because treatment with sirolimus decreases the number of circulating LAM cells in the blood and urine of patients with LAM (33), clearance of LAM cells from the lungs and reduction of LAM cell infiltrates and nodules surrounding the airways could account for the stabilization of cystic lesions and lung parenchyma in the vicinity of the cysts, and improvement in lung function.

A role of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), matrix-degrading enzymes affecting cell growth, angiogenesis, and inflammation, and cytokines and cathepsin-K activity, has been proposed as a possible mechanism for lung tissue degradation (31, 33, 34). LAM nodules show positive immunoreactivity for MMP2, MMP1, and MMP activators and inhibitors (TIMP) (35–38). Levels of TIMP are reduced in LAM lesions (38–40) and serum levels of MMP9 are reported to be elevated in patients with LAM (41), suggesting that an imbalance between MMP and TIMP could cause lung destruction (42). Doxycycline, an MMP inhibitor, has an effect on MMP production and inhibits MMP2 secretion by human LAM cells (43, 44). Doxycycline was reported to reduce serum and urine MMP9 and improve lung function in patients with LAM (45, 46). However, a small controlled study testing the effect of doxycycline in LAM showed no efficacy in preventing decline in lung function (47).

Another mechanism of cyst formation that has been suggested is disruption of lymphangiogenesis (31). Prior observations have underscored the efficacy of sirolimus in producing resolution of lymphatic tumors, effusions, and lung infiltrates. It is possible that sirolimus may abrogate new cyst formation because of its effects on lymphangiogenesis.

We conclude that sirolimus stabilizes lung function and slows down enhancement of cyst size or new cyst formation. The therapeutic effects of sirolimus seem to be sustained, with no clear evidence of resistance to continued sirolimus treatment. Sirolimus toxicity, although considerable, seems to be manageable, and most patients tolerated the drug.

Footnotes

Supported by the Intramural Research Program, National Institutes of Health, NHLBI (Protocol 95-H-0186, J.M.).

Author Contributions: A.M.T.-D. and J.M. are responsible for study design, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. A.M.J. and P.J.-W. collected and reviewed clinical data. J.Y. analyzed the computed tomography scans. M.S. is responsible for the statistical analysis.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201405-0918OC on October 20, 2014

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Ryu JH, Moss J, Beck GJ, Lee JC, Brown KK, Chapman JT, Finlay GA, Olson EJ, Ruoss SJ, Maurer JR, et al. NHLBI LAM Registry Group. The NHLBI lymphangioleiomyomatosis registry: characteristics of 230 patients at enrollment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:105–111. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1298OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormack FX. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a clinical update. Chest. 2008;133:507–516. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meraj R, Wikenheiser-Brokamp KA, Young LR, McCormack FX. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: new concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;33:486–497. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1325159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrans VJ, Yu ZX, Nelson WK, Valencia JC, Tatsuguchi A, Avila NA, Riemenschn W, Matsui K, Travis WD, Moss J. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM): a review of clinical and morphological features. J Nippon Med Sch. 2000;67:311–329. doi: 10.1272/jnms.67.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oprescu N, McCormack FX, Byrnes S, Kinder BW. Clinical predictors of mortality and cause of death in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a population-based registry. Lung. 2013;191:35–42. doi: 10.1007/s00408-012-9419-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu J, Astrinidis A, Henske EP. Chromosome 16 loss of heterozygosity in tuberous sclerosis and sporadic lymphangiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1537–1540. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.8.2104095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smolarek TA, Wessner LL, McCormack FX, Mylet JC, Menon AG, Henske EP. Evidence that lymphangiomyomatosis is caused by TSC2 mutations: chromosome 16p13 loss of heterozygosity in angiomyolipomas and lymph nodes from women with lymphangiomyomatosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:810–815. doi: 10.1086/301804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carsillo T, Astrinidis A, Henske EP. Mutations in the tuberous sclerosis complex gene TSC2 are a cause of sporadic pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6085–6090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosner M, Hanneder M, Siegel N, Valli A, Hengstschläger M. The tuberous sclerosis gene products hamartin and tuberin are multifunctional proteins with a wide spectrum of interacting partners. Mutat Res. 2008;658:234–246. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sengupta S, Peterson TR, Sabatini DM. Regulation of the mTOR complex 1 pathway by nutrients, growth factors, and stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40:310–322. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan HX, Xiong Y, Guan KL. Nutrient sensing, metabolism, and cell growth control. Mol Cell. 2013;49:379–387. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tee AR, Manning BD, Roux PP, Cantley LC, Blenis J. Tuberous sclerosis complex gene products, Tuberin and Hamartin, control mTOR signaling by acting as a GTPase-activating protein complex toward Rheb. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1259–1268. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krymskaya VP, Goncharova EA. PI3K/mTORC1 activation in hamartoma syndromes: therapeutic prospects. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:403–413. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.3.7555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castro AF, Rebhun JF, Clark GJ, Quilliam LA. Rheb binds tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2) and promotes S6 kinase activation in a rapamycin- and farnesylation-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32493–32496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bissler JJ, McCormack FX, Young LR, Elwing JM, Chuck G, Leonard JM, Schmithorst VJ, Laor T, Brody AS, Bean J, et al. Sirolimus for angiomyolipoma in tuberous sclerosis complex or lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:140–151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dabora SL, Franz DN, Ashwal S, Sagalowsky A, DiMario FJ, Jr, Miles D, Cutler D, Krueger D, Uppot RN, Rabenou R, et al. Multicenter phase 2 trial of sirolimus for tuberous sclerosis: kidney angiomyolipomas and other tumors regress and VEGF- D levels decrease. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC, Radzikowska E, Zonnenberg BA, Frost M, Belousova E, Sauter M, Nonomura N, Brakemeier S, de Vries PJ, et al. Everolimus for angiomyolipoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (EXIST-2): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381:817–824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61767-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krueger DA, Care MM, Holland K, Agricola K, Tudor C, Mangeshkar P, Wilson KA, Byars A, Sahmoud T, Franz DN. Everolimus for subependymal giant-cell astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1801–1811. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franz DN, Belousova E, Sparagana S, Bebin EM, Frost M, Kuperman R, Witt O, Kohrman MH, Flamini JR, Wu JY, et al. Efficacy and safety of everolimus for subependymal giant cell astrocytomas associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (EXIST-1): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:125–132. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka M, Wataya-Kaneda M, Nakamura A, Matsumoto S, Katayama I. First left-right comparative study of topical rapamycin vs. vehicle for facial angiofibromas in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1314–1318. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCormack FX, Inoue Y, Moss J, Singer LG, Strange C, Nakata K, Barker AF, Chapman JT, Brantly ML, Stocks JM, et al. National Institutes of Health Rare Lung Diseases Consortium; MILES Trial Group. Efficacy and safety of sirolimus in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1595–1606. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taveira-DaSilva AM, Hathaway O, Stylianou M, Moss J. Changes in lung function and chylous effusions in patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis treated with sirolimus. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:797–805, W-292–W-293. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-154-12-201106210-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moua T, Olson EJ, Jean HC, Ryu JH. Resolution of chylous pulmonary congestion and respiratory failure in lymphangioleiomyomatosis with sirolimus therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:389–390. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.186.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yao J, Taveira-DaSilva AM, Colby TV, Moss J. Computed tomography grading of lung disease in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:787–793. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten CPM, Gustafsson P, et al. ATS/ERS Task Force. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macintyre N, Crapo RO, Viegi G, Johnson DC, van der Grinten CPM, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Enright P, et al. Standardisation of the single-breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:720–735. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taveira-DaSilva AM, Stylianou MP, Hedin CJ, Hathaway O, Moss J. Decline in lung function in patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis treated with or without progesterone. Chest. 2004;126:1867–1874. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.6.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taveira-DaSilva AM, Stylianou MP, Hedin CJ, Kristof AS, Avila NA, Rabel A, Travis WD, Moss J. Maximal oxygen uptake and severity of disease in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1427–1431. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200206-593OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosas IO, Yao J, Avila NA, Chow CK, Gahl WA, Gochuico BR. Automated quantification of high-resolution CT scan findings in individuals at risk for pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2011;140:1590–1597. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henske EP, McCormack FX. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a wolf in sheep’s clothing. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3807–3816. doi: 10.1172/JCI58709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abbott GF, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Frazier AA, Franks TJ, Pugatch RD, Galvin JR. From the archives of the AFIP: lymphangioleiomyomatosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2005;25:803–828. doi: 10.1148/rg.253055006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai X, Pacheco-Rodriguez G, Haughey M, Samsel L, Xu S, Wu HP, McCoy JP, Stylianou M, Darling TN, Moss J. Sirolimus decreases circulating lymphangioleiomyomatosis cells in patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Chest. 2014;145:108–112. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pacheco-Rodriguez G, Kumaki F, Steagall WK, Zhang Y, Ikeda Y, Lin JP, Billings EM, Moss J. Chemokine-enhanced chemotaxis of lymphangioleiomyomatosis cells with mutations in the tumor suppressor TSC2 gene. J Immunol. 2009;182:1270–1277. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chilosi M, Pea M, Martignoni G, Brunelli M, Gobbo S, Poletti V, Bonetti F. Cathepsin-k expression in pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:161–166. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayashi T, Fleming MV, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Liotta LA, Moss J, Ferrans VJ, Travis WD. Immunohistochemical study of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their tissue inhibitors (TIMPs) in pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) Hum Pathol. 1997;28:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(97)90061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsui K, Takeda K, Yu ZX, Travis WD, Moss J, Ferrans VJ. Role for activation of matrix metalloproteinases in the pathogenesis of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:267–275. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-0267-RFAOMM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krymskaya VP, Shipley JM. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a complex tale of serum response factor-mediated tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-3 regulation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:546–550. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.F267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhe X, Yang Y, Jakkaraju S, Schuger L. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-3 downregulation in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: potential consequence of abnormal serum response factor expression. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:504–511. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0124OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Papakonstantinou E, Dionyssopoulos A, Aletras AJ, Pesintzaki C, Minas A, Karakiulakis G. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases and their endogenous tissue inhibitors in skin lesions from patients with tuberous sclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:526–533. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Odajima N, Betsuyaku T, Nasuhara Y, Inoue H, Seyama K, Nishimura M. Matrix metalloproteinases in blood from patients with LAM. Respir Med. 2009;103:124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goncharova EA, Goncharov DA, Fehrenbach M, Khavin I, Ducka B, Hino O, Colby TV, Merrilees MJ, Haczku A, Albelda SM, et al. Prevention of alveolar destruction and airspace enlargement in a mouse model of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) Sci Transl Med 20124154ra134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang WY, Clements D, Johnson SR. Effect of doxycycline on proliferation, MMP production, and adhesion in LAM-related cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;299:L393–L400. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00437.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moir LM, Ng HY, Poniris MH, Santa T, Burgess JK, Oliver BGG, Krymskaya VP, Black JL. Doxycycline inhibits matrix metalloproteinase-2 secretion from TSC2-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts and lymphangioleiomyomatosis cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:83–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01344.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pimenta SP, Baldi BG, Acencio MM, Kairalla RA, Ribeiro de Carvalho CR. Doxycycline use in patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis: safety and efficacy in metalloproteinase blockade. J Bras Pneumol. 2011;37:424–430. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132011000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pimenta SP, Baldi BG, Kairalla RA, Carvalho CR. Doxycycline use in patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis: biomarkers and pulmonary function response. J Bras Pneumol. 2013;39:5–15. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37132013000100002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang WY, Cane JL, Kumaran M, Lewis S, Tattersfield AE, Johnson SR. A 2-year randomised placebo-controlled trial of doxycycline for lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:1114–1123. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00167413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]