Abstract

Rationale: The rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) contains central respiratory chemoreceptors (retrotrapezoid nucleus, RTN) and the sympathoexcitatory, hypoxia-responsive C1 neurons. Simultaneous optogenetic stimulation of these neurons produces vigorous cardiorespiratory stimulation, sighing, and arousal from non-REM sleep.

Objectives: To identify the effects that result from selectively stimulating C1 cells.

Methods: A Cre-dependent vector expressing channelrhodopsin 2 (ChR2) fused with enhanced yellow fluorescent protein or mCherry was injected into the RVLM of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-Cre rats. The response of ChR2-transduced neurons to light was examined in anesthetized rats. ChR2-transduced C1 neurons were photoactivated in conscious rats while EEG, neck muscle EMG, blood pressure (BP), and breathing were recorded.

Measurements and Main Results: Most ChR2-expressing neurons (95%) contained C1 neuron markers and innervated the spinal cord. RTN neurons were not transduced. While the rats were under anesthesia, the C1 cells were faithfully activated by each light pulse up to 40 Hz. During quiet resting and non-REM sleep, C1 cell stimulation (20 s, 2–20 Hz) increased BP and respiratory frequency and produced sighs and arousal from non-REM sleep. Arousal was frequency-dependent (85% probability at 20 Hz). Stimulation during REM sleep increased BP, but had no effect on EEG or breathing. C1 cell–mediated breathing stimulation was occluded by hypoxia (12% FIO2), but was unchanged by 6% FiCO2.

Conclusions: C1 cell stimulation reproduces most effects of acute hypoxia, specifically cardiorespiratory stimulation, sighs, and arousal. C1 cell activation likely contributes to the sleep disruption and adverse autonomic consequences of sleep apnea. During hypoxia (awake) or REM sleep, C1 cell stimulation increases BP but no longer stimulates breathing.

Keywords: EEG, hypoxia, medulla oblongata, respiration, rostral ventrolateral medulla

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

The C1 neurons are important lower brainstem nodal points for the control of sympathetic tone to cardiovascular organs. At rest, the function of these neurons is to minimize blood pressure fluctuations, but they are powerfully activated by carotid body stimulation and increase blood pressure in response to hypoxia.

What This Study Adds to the Field

This optogenetic study in rats shows that selective activation of the C1 neurons increases breathing as well as blood pressure and faithfully produces sighs and arousal from non-REM sleep. C1 neuron activation therefore reproduces most of the effects of hypoxia, including arousal. These observations suggest that the C1 neurons could contribute both to sleep disruption and to the adverse cardiovascular effects of apneas.

Sleep and the chemical control of breathing interact in two ways. The intensity of the hypercapnic or hypoxic ventilatory response depends on the state of vigilance, and, conversely, chemoreceptor stimulation by hypoxia or hypercapnia disrupts sleep (1–5). Neither of these phenomena has been thoroughly explained (6). One possibility could be that the degree of respiratory stimulation caused by activation of central respiratory chemoreceptors (CRCs) and subsets of hypoxia-activated neurons is state-dependent and that the same neurons also contribute to asphyxia-induced arousal. Two types of rostral ventrolateral medullary (RVLM) neurons—the retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN) and C1 cells—are possible candidates (for reviews, see References 7 and 8). RTN neurons are highly activated by CO2 and are presumptive CRCs (8–11). The nearby C1 cells are sympathoexcitatory and intensely activated by carotid body stimulation (7, 12–14). Channelrhodopsin 2 (ChR2)-mediated optogenetic activation of a mixed population of RTN and C1 neurons produces arousal from sleep, along with breathing stimulation, a rise in blood pressure (BP), and sighs (15). These effects, with the exception of the rise in BP, are greatly attenuated or absent during REM sleep (15). Selective activation of these cells has been possible because, unlike other types of RVLM neurons, RTN and C1 cells are selectively transduced by lentiviral vectors that contain the Phox2b-responsive artificial promoter PRSx8 (16–18). However, doubts persist as to which cardiorespiratory effects are produced by RTN versus C1 neurons. Although the dominant view has long been that the RVLM C1 cells are specialized in regulating the vasomotor sympathetic outflow and BP whereas RTN selectively regulates breathing, the C1 cells also activate breathing in mice, respond to hypoxia, and activate neurons with well-documented arousal-promoting roles such as the locus coeruleus (7, 8, 19–25). The objective of the present study was therefore to determine which cardiorespiratory effects are produced by selective activation of the C1 cells rather than a mixture of C1 and RTN neurons and, in particular, whether selective C1 neuron stimulation is wake-promoting and increases breathing. To accomplish this goal, we used transgenic rats in which Cre-recombinase is expressed under the control of the tyrosine-hydroxylase promoter (TH-Cre rats) (26), and we introduced ChR2 selectively in the C1 cells using stereotaxic injections of a Cre-dependent adeno-associated vector (27). This method allowed us to explore the cardiorespiratory effects resulting from C1 cell stimulation in intact rats during various stages of vigilance and to assess whether such stimulation can produce arousal from sleep.

Methods

All experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee. The tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)::Cre recombinase rats were generated by Drs. I. Witten (Princeton University, Princeton, NJ) and K. Deisseroth (Stanford University, Stanford, CA) (26) and bred in-house as heterozygous with Long-Evans rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA). Eight females (300–350 g at the time of experimentation) and 19 males (350–550 g) were used for experiments. The reported physiological data were obtained from 8 anesthetized rats (unit recordings), 13 conscious rats (7 rats with ChR2-transduced C1 neurons and 6 controls without transduced cells) in which EEG and neck EMG recordings, unilateral optical stimulation of the left ventrolateral medulla, telemetric BP recordings, and whole-body plethysmography were simultaneously performed as described elsewhere (15). Three or four injections of Cre-dependent viral vector (AAV2-DIO-EF1α-ChR2-EYFP) totaling 400–600 nl were made in the left RVLMs of rats anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (75 mg/kg), xylazine (5 mg/kg), and acepromazine (1 mg/kg) given intraperitoneally. Extracellular unit recordings (n = 8) were conducted in anesthetized rats (0.7 g/kg urethane i.v. plus α-chloralose, 30 mg/kg/h i.v.) with bilateral vagotomy, paralysis (vecuronium bromide, 0.05 mg/kg/h i.v.), and artificial ventilation. Analyses for normality and differences within and between groups were performed using paired or unpaired Student’s t test or repeated measures one- or two-way analysis of variance with the appropriate posttest. If data were not normally distributed, the equivalent nonparametric tests were performed. Statistical analysis was conducted using PRISM software (v. 6.00; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). All values are expressed as mean ± SEM, unless otherwise noted. An expanded Methods section is available in the online supplement.

Results

Histology

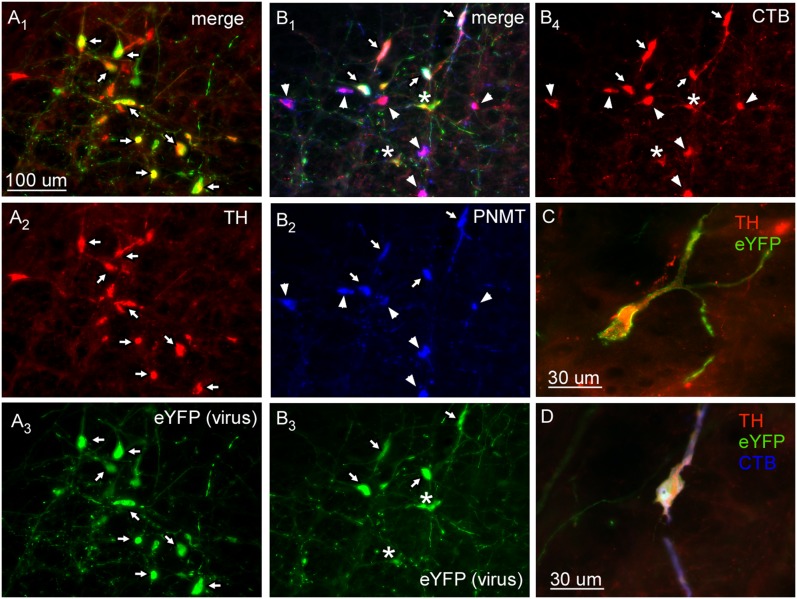

The location and phenotype of the transduced neurons (positive for ChR2 fused with enhanced yellow fluorescent protein [ChR2-EYFP]) were examined by immunohistochemistry in three noninstrumented rats and five instrumented rats in which optical stimulation was used to evoke physiological responses. In this cohort, most transduced neurons (94.6 ± 0.1%) were demonstrably catecholaminergic (i.e., TH- or phenylethanolamine-N-methyl transferase (PNMT)-immunoreactive, as illustrated in Figures 1A and 1C. In three rats in which the retrograde tracer cholera toxin B (CTB) was injected into the upper thoracic spinal cord, 94.3 ± 0.2% of the ChR2-EYFP-expressing neurons were spinally projecting (i.e., contained CTB; Figures 1B and 1D). In all cases, the transduced neurons were confined to the RVLM. Their rostrocaudal distribution (11 rats) is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Characterization of neurons transduced by ChR2-EYFP adeno-associated virus type 2. (A) Transduced cells are catecholaminergic. (A1) Merged photomicrograph of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunoreactive (ir) (revealed by Cy3, red) (A2) and ChR2-EYFP (i.e., virally transduced; revealed by Alexa Fluor 488, green) (A3). Note the complete overlap of TH and EYFP (arrows). (B) Virally transduced cells are spinally projecting C1 neurons. (B1) Photomicrograph of phenylethanolamine-N-methyl transferase (PNMT) ir (revealed by DyLight 649, blue) (B2) with ChR2-EYFP-transduced cells (revealed by Alexa Fluor 488, green) (B3) that are retrogradely labeled with cholera toxin B (CTB) from thoracic spinal cord injections (revealed by Cy3, red) (B4). Arrows point to triple-labeled neurons. Asterisks indicate non-PNMT spinally projecting neurons. Arrowheads indicate nontransduced C1 bulbospinal neurons. (C) Example of catecholaminergic (TH positive, red) neuron transduced with ChR2-EYFP (green). (D) Example of catecholaminergic (TH positive, red) bulbospinal (CTB, blue) neuron transduced with ChR2-EYFP (green).

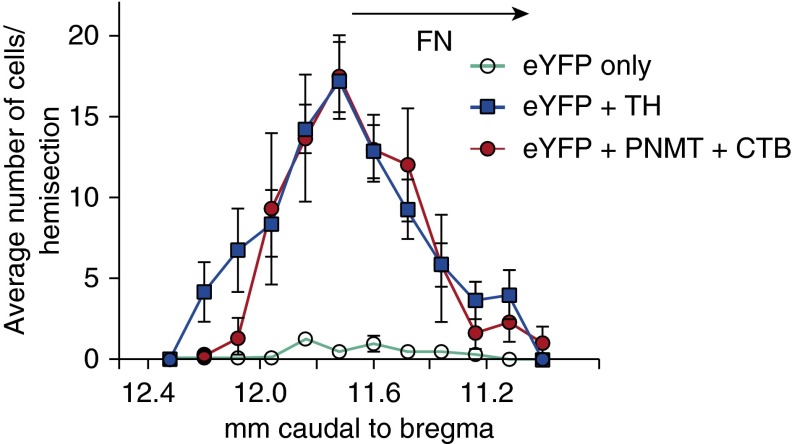

Figure 2.

Rostrocaudal distribution of ChR2-EYFP-transduced neurons. The number of transduced catecholaminergic neurons (EYFP+TH) and transduced neurons without detectable tyrosine hydroxylase (EYFP only) were counted per section in a one-in-six series of 30-μm coronal sections in eight rats. Expression of ChR2-EYFP in presympathetic C1 neurons (immunoreactive for both PNMT and CTB) was determined in three other rats with spinal injections of CTB. Error bars show SEM. FN shows the location of the facial motor nucleus.

Photoactivation of the C1 Cells and Network Activation of RTN and Respiratory Neurons in Anesthetized Rats

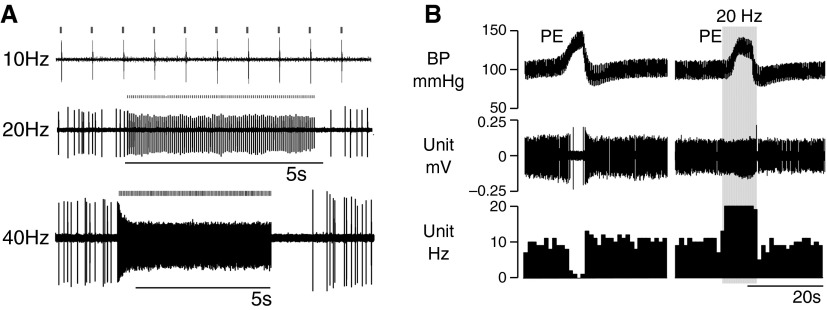

Single units were recorded in the left C1 and RTN regions of eight anesthetized rats. Seventeen cells were found to respond with a single action potential per light pulse. These neurons were active at rest and, with a single exception, could be silenced by raising BP with phenylephrine, and therefore they had properties typical of C1 bulbospinal presympathetic neurons (Figure 3) (28). These neurons could be activated on a pulse-by-pulse basis up to 40 Hz (Figures 3A and 3B). Optogenetic activation was so robust that the neurons could be driven at 20 Hz even while receiving inhibitory inputs from the baroreceptors (Figure 3B). We chose to deliver light pulses of 5 ms or less (1–5 ms; see Figure E1A in the online supplement) because longer light pulses (e.g., 10 ms) caused doublets (see Figures E1A and E1B). Each action potential occurred 4–5 ms after the onset of the light pulse (see Figure E1B). This latency corresponds to the time required for the light to depolarize the neurons to action potential threshold (29). Many baroinhibited neurons could not be photoactivated (n = 21). Nine had the same low discharge rate (4.7 ± 0.7 Hz) as the light-activated neurons (n = 16; 7.4 ± 2 Hz) and were probably nontransduced C1 cells. The rest of the light-insensitive baroinhibited neurons had a higher average resting discharge rate (n = 12; 20.8 ± 1.7 Hz) and were likely a mix of C1 and non-C1 presympathetic neurons (28). The physical properties of all recorded neurons with spontaneous activity are summarized in Figure E2.

Figure 3.

Photostimulation of baroinhibited neurons in anesthetized rats. (A) Example of single RVLM neuron that generated one action potential per light pulse up to 40 Hz. (B) Example of a single baroinhibited RVLM neuron. This neuron could be silenced by a moderate rise in blood pressure (BP) (left excerpt). Photostimulation at 20 Hz could drive unit activity at 20 Hz even while receiving inhibitory inputs from the baroreceptors. PE = phenylephrine (5 μg/kg i.v.).

In the same experiments we also recorded from eight RTN chemoreceptor neurons located ventral to the facial motor nucleus. As also described elsewhere (30), these neurons were activated by hypercapnia (up to 8–12 Hz with 10% end-expiratory CO2), silenced by lowering end-expiratory CO2 below 4%, and insensitive to BP elevation (Figure 4A). They discharged tonically or exhibited a mild respiratory modulation. RTN neurons were mildly but significantly light-activated in normocapnia (4–5% end-tidal CO2 [ETco2]) and hypercapnia (5–10% ETco2), but never responded on a pulse-by-pulse basis to light (Figures 4A and 4C). Their activation was therefore a network effect.

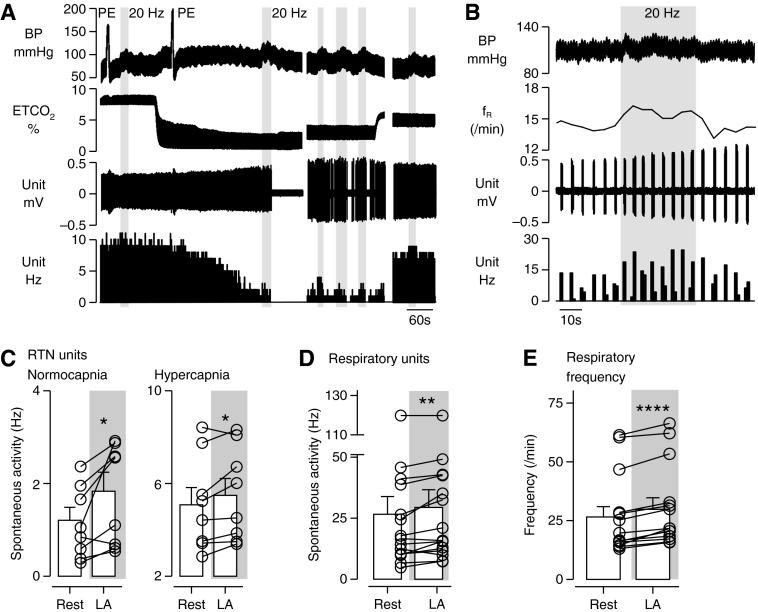

Figure 4.

Photostimulation of C1 neurons produced network activation of RTN neurons and respiratory neurons in anesthetized rats. (A) Example of a single CO2-sensitive RTN neuron that was indirectly (i.e., synaptically) activated by photostimulation of C1 neurons at low and high levels of end-tidal CO2 (ETco2). End-expiratory CO2 was changed by adding variable concentrations of this gas to the breathing mixture. Photostimulation of C1 neurons (gray bars) occurred at 20-Hz blue light with 5-ms pulse width for 10–20 s. Top trace: Arterial blood pressure (BP). RTN neuronal activity is unaffected by ramp increases in blood pressure with phenylephrine (PE, 5 μg/kg i.v.). Middle traces: ETCO2 and extracellular action potentials. Lower trace: Integrated rate histogram (bin size = 1 s) shows the increases in RTN unit firing rate from baseline by C1 stimulation at various levels of ETco2. (B) Example of a respiratory neuron that increased firing rate and cycle frequency (i.e., respiratory frequency [fR]) with photostimulation of C1 neurons (20 Hz for 20–30 s). (C) Average discharge frequency of eight RTN neurons at baseline (4–5% ETco2) and during C1 cell photostimulation. (D) Mean discharge frequency in the active phase of 13 respiratory neurons at rest (4–5% ETco2) and during C1 cell photostimulation. (E) Average respiratory cycle frequency at rest and during C1 cell photostimulation (n = 9). Paired Student’s t test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.001.

We also took recordings from 15 phasically active respiratory neurons located in the RVLM (Bötzinger region; Figures 4B, 4D, and 4E) and measured the frequency of the units’ bursts as a surrogate measure of the respiratory pattern generator cycle (Figures 4B and E). Respiratory unit activity and respiratory frequency were both mildly but significantly elevated by stimulation of the C1 cells.

In summary, 43% (16 of 37) of the sampled baroinhibited neurons exhibited the hallmark response of ChR2-expressing neurons—namely, a single action potential per light pulse. These ChR2-expressing, barosensitive neurons comprised 94% (16 of 17) of all light-activated neurons sampled. Consistent with the histological data, these neurons had the properties of C1 neurons, which, in this brain region, innervate the spinal cord and control sympathetic vasomotor tone. These experiments also revealed that C1 cell stimulation activates the central respiratory pattern generator, possibly by activating RTN neurons.

State-Dependent Effects of C1 Cell Stimulation on Breathing and Blood Pressure

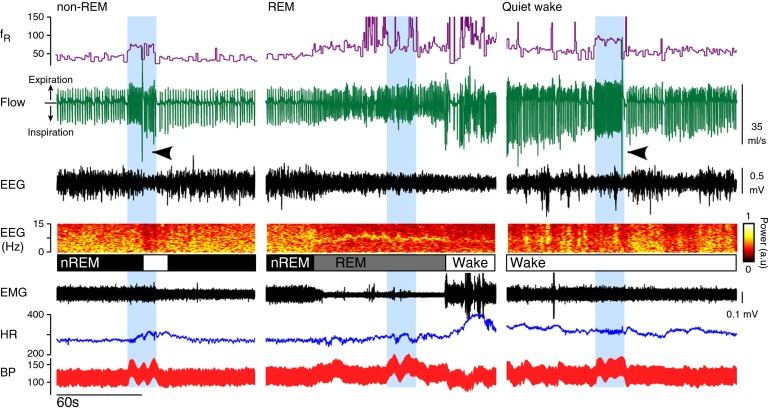

Following weeks of implantation, the optical fibers produced little observable tissue damage (see Figure E3). C1 cell stimulation when the rats were in non-REM sleep elevated BP, activated breathing, caused sighing, and produced arousal (EEG desynchronization) (Figure 5, left panel). During REM sleep (Figure 5, middle panel), C1 cell stimulation elevated BP but had no effect on respiration and did not cause arousal from this state (see Figure E4). During quiet wake (Figure 5, right panel), C1 cell stimulation caused effects very similar to those during non-REM sleep—namely, increased BP, breathing, and sighing. Non-REM sleep was determined by immobility, the presence of a large amount of δ power in the EEG, and regular cardiorespiratory parameters (see Table E1 in the online supplement). REM sleep was identified by muscle atonia and a characteristic concentration of EEG power at 6–7 Hz (θ rhythm). Breathing during REM sleep exhibited periods of high variability or was regular but shallow and faster than during non-REM sleep. C1 cell stimulation failed to activate breathing or produce a state change during either manifestation of REM sleep (see Figure E4).

Figure 5.

State-dependent effects of C1 cell stimulation on breathing and BP. Left panel: Photostimulation of C1 neurons (20 Hz for 20 s; blue bar) during non-REM sleep (nREM) increased breathing (fR; respiratory frequency) and BP and produced arousal (EEG desynchronization and reduced δ power) with a sigh (black arrowheads). Middle panel: Photostimulation of C1 neurons during REM sleep elevated BP, but had no effect on respiratory frequency and did not produce sighs or arousal from REM sleep. Right panel: Photostimulation of C1 neurons in a quiet wake state (wake) increased BP and breathing and evoked a sigh. fR trace is capped at 150 breaths/min. HR = heart rate.

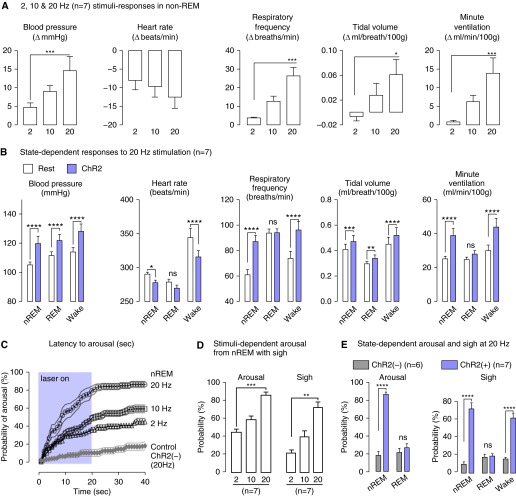

The quantitative results from seven rats are described in Figure 6. During non-REM sleep, BP, respiratory frequency, and minute volume were all significantly increased by C1 cell stimulation in a stimulation frequency–dependent manner [Figure 6A; ChR2(−) controls described in Figure E5]. With 20-Hz stimulation, these parameters were activated equally during non-REM sleep and quiet wake (Figure 6B). During REM sleep, C1 cell stimulation still elevated BP but did not increase respiratory frequency or minute ventilation. Changes in heart rate were influenced by several independent factors, including resting heart rate, baroreflex-mediated bradycardia, and whether sleep–wake transition occurred (see also Figure 7). Notably, C1 stimulation produced a large bradycardia in the waking state, where resting heart rate was highest, and a minor bradycardia in REM sleep, when resting heart rate was lowest.

Figure 6.

Group data for light pulse frequency- and state-dependent effects of C1 cell activation on blood pressure, breathing, and state of vigilance. (A) Average change in cardiorespiratory parameters elicited during non-REM (nREM) sleep by increasing the photostimulation frequencies of C1 neurons (2, 10, and 20 Hz for 20 s; one-way repeated measures [RM] analysis of variance [ANOVA], Dunn’s post hoc test). (B) Average cardiorespiratory parameters at rest (open columns) and during the 20-Hz, 20-s photostimulation trials (shaded columns) in nREM sleep, REM sleep, and quiet wake states (two-way RM ANOVA, Bonferroni’s post hoc test). (C) Probability of arousal (1-s bins, mean ± SE, n = 7 rats) during photostimulation of ChR2-transduced C1 neurons (20 s at 2, 10, or 20Hz) in nREM sleep. The control rats ([ChR2(−), n = 6]) received a 20-Hz light stimulus, but had no transduced neurons. (D) Cumulative probability of arousal from nREM sleep and sighs as a function of photostimulation frequency in ChR2(+) rats (one-way ANOVA, Dunn’s post hoc test). (E) Cumulative probability of arousal from nREM or REM sleep by 20-Hz photostimulation of C1 neurons. Probability of a sigh related to the arousal from sleep, or evoked in the quiet wake state, with 20-Hz photostimulation of C1 neurons (two-way RM ANOVA, Bonferroni’s post hoc test). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005, ****P < 0.001.

Figure 7.

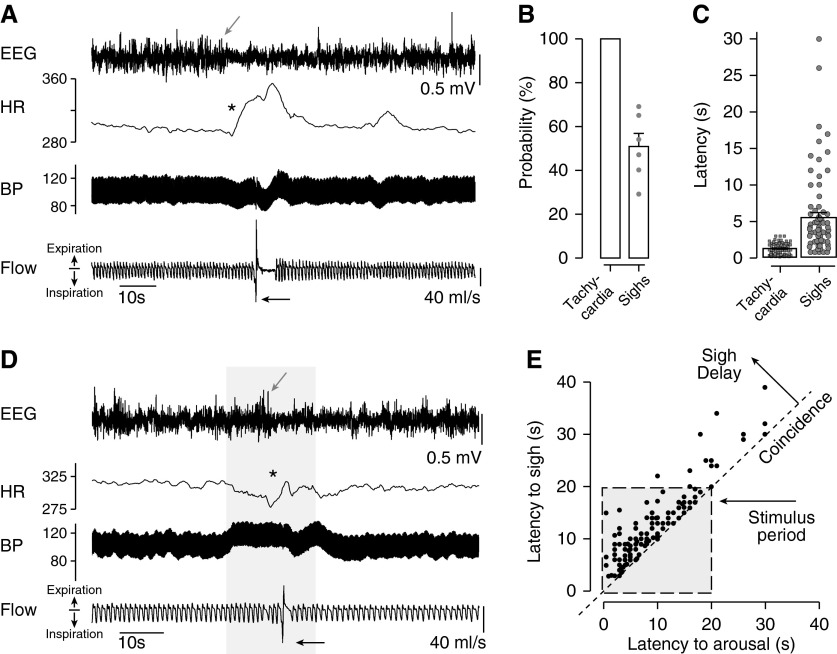

Spontaneous and C1-evoked arousal from non-REM sleep in rats resulted in a similar sequence of cortical desynchronization, tachycardia, and sighs. (A) Spontaneous arousal from non-REM sleep (gray arrow) is accompanied by tachycardia (asterisk) and sighs (black arrow). (B) Probability of tachycardia (100%) and sighs (51%) during spontaneous EEG desynchronization in non-REM sleep (recorded in n = 6 rats; >20 events/rat). (C) During spontaneous arousal, onset of tachycardia followed onset of EEG desynchronization by <1 s on average) and sighs by less than 6 s on average (n = 6 rats; >30 events/rat). (D) 20-Hz photostimulation of C1 cells in non-REM sleep produced the same stereotypic sequence of EEG desynchronization (gray arrow) with tachycardia (asterisk) and sighs (black arrow). Arousal tachycardia was blunted by C1-evoked pressor response that produced a reflex bradycardia throughout the 20-s stimulus period. (E) x–y scatterplot of the latency to sighs relative to the onset of arousal produced by C1 cell stimulation. Sighs follow arousal. HR = heart rate.

Effect of C1 Cell Stimulation on Sleep

C1 cell stimulation during non-REM sleep caused arousal with sighs (Figures 5, 6C–6E, 7B, and 8). Arousal was defined by EEG desynchronization (>3 s) and was associated with a stereotyped sequence of cardiorespiratory activation (tachycardia, sigh) and infrequently with bodily movements. Arousal latency was determined in each rat during multiple stimulation episodes at 2, 10, and 20 Hz, and the resulting values were used to construct plots describing the cumulative arousal probability as a function of time after stimulus onset (Figure 6C). At 20 Hz, arousal from non-REM sleep occurred with a probability of 85%. C1 cell stimulation also frequently triggered a sigh upon arousal. With 20-Hz stimulations, sighs occurred with a probability of 72%, representing an 85% coincidence with C1-evoked arousal (Figure 6D). A 20-Hz stimulation in the awake state also reliably triggered sighs (Figures 5 and 6E). By contrast, this same stimulation applied in REM sleep did not cause sighs or wake from REM (Figures 5 and 6D; see Figure E4).

Figure 8.

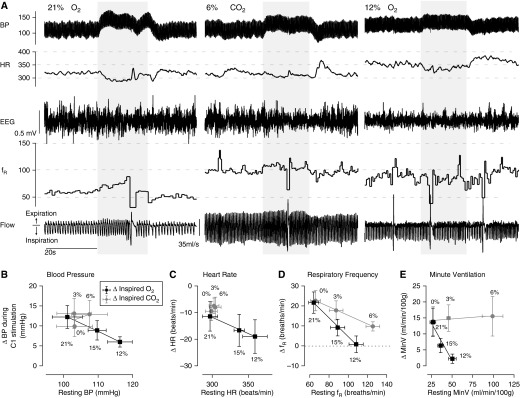

Hypoxia, but not hypercapnia, occluded the increase in breathing by C1 cell stimulation. (A) Photostimulation of C1 neurons (20 Hz, 20 s) at rest (left panel; 21% O2 balanced in N2) or during hypercapnia (middle panel; 6% CO2, 21% O2 balanced in N2) increased breathing rate, elevated BP, and caused bradycardia. In hypoxia (right panel; 12% O2 balanced in N2), photostimulation of C1 neurons still elevated BP and caused bradycardia, but no longer stimulated breathing. Group data summarizing the effects of selective C1 cell stimulation on blood pressure (B), heart rate (C), respiratory frequency (D), and minutes of ventilation (E) under hypoxic or hypercapnic conditions (n = 7). x–y plots show the average change from rest with C1 cell stimulation (y) plotted against the resting baseline value (x) in each condition.

Sighs were also frequently observed during spontaneous transitions from sleep to wakefulness (Figures 7A and 7D), but never during sleep itself. In six animals, we observed sleep and sleep–wake transitions without optogenetic stimulation (summarized in Figure 7). The spontaneous arousal from sleep exhibited a highly stereotyped pattern starting with EEG desynchronization and tachycardia. The mean increase in heart rate was 55 ± 2 beats per minute, mean onset latency was 1.3 seconds, and observed with every EEG desynchronization (>3 s; 100% coincidence). Sighs were observed in 51 ± 6% of all spontaneous arousals from non-REM sleep, with 79% of sighs occurring within 7 seconds of EEG desynchronization. This arousal sequence was similar to those elicited by stimulation of C1 cells (Figure 7), with 89% of evoked sighs also falling within 7 seconds of EEG desynchronization (Figure 7B). However, the tachycardia associated with C1-evoked arousal was often blunted, presumably by the baroreflex (Figure 7B).

Effects of Hypoxia or Hypercapnia on the Cardiorespiratory Responses to C1 Cell Stimulation

In these experiments, we tested whether the cardiorespiratory effects produced by C1 stimulation during eupnea (non-REM sleep or quiet awake) were occluded by hypercapnia (3% and 6% FiCO2, respectively) or poikilocapnic hypoxia (15% and 12% FiO2, respectively, balance nitrogen). As shown in Figure 8, the respiratory stimulation was occluded by hypoxia (see also Figure E8). In contrast, C1 cell stimulation under hypercapnia still increased breathing rate and minute volume, despite the fact that 6% CO2 increased breathing significantly more than 12% O2 (Figure 8; see also Figure E8). The rise in BP and reflex bradycardia evoked by C1 cell stimulation persisted under hypoxia (Figures 8B and 8C; see also Figure E9).

The effects of poikilocapnic hypoxia or hypercapnia on the state of vigilance and on cardiorespiratory outflow are summarized in Figures E6–E9. Notably, hypoxia triggered sighs (see Figure E6) and stimulated respiratory frequency but not tidal volume, whereas hypercapnia increased both respiratory frequency and tidal volume without producing sighs. Hypoxia was also a more potent wake-promoting stressor, as can be observed in the sigh incidence, EEG desynchronization, and elevated heart rate and BP (see Figures E6, E7, and E9). Thus, the wake promotion, sighs, and respiratory frequency stimulation by hypoxia or by C1 cell stimulation exhibit striking similarities.

Discussion

Selective activation of the rostral C1 neurons in conscious rats produces tachypnea, sighs, and sleep-state–dependent arousal in addition to the expected increase in BP (31). We also provide evidence that the tachypnea could be partially mediated via RTN activation. Because the rostral C1 neurons are vigorously activated by hypotension and carotid body stimulation, we conclude that these cells probably contribute to the barorespiratory reflex (32) and to the cardiorespiratory and arousal responses to hypoxia (1, 4, 33).

Selective Expression of ChR2 by Bulbospinal C1 Neurons in TH-Cre Rats

Virtually all catecholaminergic (TH-immunoreactive) neurons located in the RVLM of rats express PNMT and therefore are C1 neurons (34–36). These C1 cells, as opposed to those that are located more caudally in the medulla oblongata, innervate the spinal cord and regulate sympathetic outflow and BP (7, 35, 37). However, these bulbospinal neurons also innervate other brain regions, such as the dorsolateral pons, the periaqueductal gray matter, the ventrolateral medulla, and, sparsely, the hypothalamus (38). Ninety-five percent of transduced cells in the present experiments were bulbospinal C1 neurons. A very small number of ChR2-expressing neurons did not contain detectable levels of TH. These neurons could represent false-negative immunohistochemical results or could express very low levels of catecholaminergic enzyme (28). The C1 neurons are active under anesthesia and powerfully inhibited by baroreceptor stimulation (28). Our unit recordings in anesthetized TH-Cre rats confirmed that a large proportion of RVLM neurons with these characteristics were activated by light pulses and could follow photostimulation up to 40 Hz. Neuronal activation was very robust because it could overcome the strong GABA-mediated inhibition elicited by baroreceptor stimulation (39). None of the RTN neurons exhibited the signature response of ChR2-expressing neurons—the production of action potentials synchronized with light pulses (40). Furthermore, the fusion protein (mCherry or EYFP) was undetectable by histology in RTN neurons, even after signal amplification with immunohistochemistry.

C1 Cell Stimulation Reproduces the Rise in BP and Several Other Effects of Moderate Hypoxia

In TH-Cre rats, as in other strains, hypoxia causes tachypnea with minimal increase in VT, a rise in BP, arousal, and sighing. Selective activation of the rostral C1 cells was sufficient to reproduce these effects. The BP effect conforms to expectations because the rostral C1 neurons are sympathoexcitatory and activate sympathetic efferents, largely via their direct projections to sympathetic preganglionic neurons (7, 41, 42). The observations that selective C1 cell stimulation causes arousal, sighs, and tachypnea are novel findings. The C1 neurons are vigorously activated by peripheral chemoreceptor stimulation (43). That their activation in conscious rats mimics multiple effects of hypoxia suggests that they contribute to these responses. The extent of this contribution was not revealed in the present study and requires further experiments.

C1 Cell Stimulation Activates Breathing

In previous studies, opto- or pharmacogenetic manipulation of the C1 cells has been achieved using lentiviruses that also transduce RTN neurons, leaving lingering doubts as to which cell type mediates the observed physiological changes (16, 42, 44, 45). The consensus has been that RTN neurons regulate breathing, whereas the C1 cells regulate sympathetic tone and BP. The present results support this overall interpretation, but show it to be an approximation. C1 cell activation also increases breathing and probably does so, at least partly, by activating RTN neurons.

Selective C1 cell stimulation produces much less breathing stimulation than combined stimulation of C1 and RTN neurons (e.g., 20-Hz stimulation: ΔfR = ∼25 breaths/min vs. >100 breaths/min [44]). Therefore, the respiratory stimulation elicited by combined activation or inhibition of RTN and C1 cells in conscious rats probably results predominantly from RTN neuron activation, as previously suggested (16, 44, 45).

The C1 neurons could activate breathing via their projections to the lateral parabrachial nucleus, the ventrolateral medulla, the periaqueductal gray matter, or even hypothalamic wake-promoting networks (23, 46–50). Arousal was not a prerequisite for breathing stimulation. C1 cell stimulation increased breathing in awake rats, and, during non-REM sleep, the tachypnea occurred immediately upon stimulation, whereas EEG desynchronization happened at any time during the stimulation period in a probabilistic manner. The most persuasive evidence that breathing stimulation evoked by C1 cell stimulation could be partly mediated via the RTN was that RTN neurons were activated by C1 cell stimulation in anesthetized rats. Another indication is that C1 neurons innervate the RTN region (23, 46). The respiratory stimulation caused by C1 cell stimulation in conscious rats was occluded by hypoxia, but not by moderate hypercapnia. Hypoxia produces respiratory alkalosis, which should strongly inhibit putative CRCs such as RTN neurons (30). This effect may render them unresponsive to mild excitatory inputs such as those from the C1 cells and could explain the loss of the ventilatory stimulation. No such occlusion should occur during moderate hypercapnia, because RTN neurons are active and should remain responsive to C1 stimulation, as was observed in anesthetized rats.

The occlusion by hypoxia has an alternative explanation—namely that the C1 neurons might be so strongly activated that optogenetic stimulation at 20 Hz failed to raise their discharge rate any further. The C1 cells are indeed very strongly activated by hypoxia, at least under anesthesia (12), and, in the conscious state (present data), the BP rise produced by stimulating the C1 cells tended to be reduced during hypoxia.

In short, C1 cell stimulation increases breathing, predominantly by boosting frequency. This effect is occluded by hypoxia and could be at least partially mediated via activation of CRCs such as RTN neurons.

C1 Cell Activation Evokes Sighs

Hypoxia triggered sighs in TH-Cre rats (Figures 5–8; see also Figure E6), as is the case in other strains and species (51). Sighing is elicited by combined activation of C1 and RTN neurons (15). In the present study, we show that sighing is reliably triggered by selective activation of the C1 cells during normoxia. Hypercapnia does not trigger sighs and, in fact, attenuates hypoxia-induced sighing (51). Whether selective stimulation of RTN neurons which mediate a substantial proportion of the hypercapnic ventilatory response would also evoke sighs is an open question (45). Augmented breaths, including sighs, promote respiratory instability and are implicated in triggering periods of sleep-disordered breathing (51). C1 cells are activated by hypoxia and promote sighs. Therefore, these neurons could conceivably contribute to sleep-disordered breathing at high elevation or in other forms of central sleep apnea. Sighs are generated by activation of a subtype of pre-Bötzinger complex pacemaker neurons that rely on persistent sodium current for their bursting and whose bursts are amplified by β-adrenergic receptor stimulation (52). The cognate catecholamine could conceivably originate from the C1 cells or from lower brainstem noradrenergic neurons that are activated by the latter (24, 52).

C1 Cell Stimulation Causes Arousal from Non-REM Sleep Only

Previously, we showed that combined stimulation of RTN and rostral C1 neurons produces a high probability of arousal from non-REM sleep and virtually no arousal from REM sleep (15). As shown in the present study, selective activation of the C1 cells reproduces these effects. We can therefore conclude that neither C1 nor RTN stimulation causes arousal from REM sleep. However, whether selective activation of RTN chemoreceptors produces arousal from non-REM sleep remains unanswered. The C1 cells presumably cause arousal via multiple mechanisms, including via direct activation of wake-promoting regions such as the locus coeruleus, lateral parabrachial nucleus, raphe, and orexin neurons, as suggested by anatomical and neurophysiological evidence (5, 24, 53). Many of these known or presumed C1 targets are themselves profoundly inhibited during REM sleep, including, but not limited to, the locus coeruleus and raphe 5HT neurons, which could partly explain the inability of C1 cell stimulation to cause arousal from this stage of sleep (54–57).

Conclusions

Selective activation of a population of hypoxia-sensitive C1 cells located at the rostral end of the ventrolateral medulla is sufficient to reproduce many of the effects of hypoxia in rats, including the rise in BP, respiratory stimulation, sighs, and arousal from non-REM sleep. The C1 cells are highly collateralized and presumably contribute to the various effects of hypoxia via their projections to several pontomedullary structures in addition to the sympathetic preganglionic neurons. The C1 neurons, like the RTN, have been identified in the human ventrolateral medulla (58, 59). Based on the present data, activation of the C1 cells is likely to contribute both to the cardiorespiratory effects and to the sleep disruption elicited by obstructive and other forms of apneas in humans. Loss-of-function experiments will eventually be required to determine which portion of the various effects of hypoxia can be attributed to the activation of the C1 cells.

Footnotes

Supported by grants HL28785 and HL74011 to P.G.G. from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Author Contributions: P.G.R.B., R.L.S., and P.G.G.: designed the experiments, collected data, performed analysis, and wrote the manuscript. S.B.G.A.: contributed to experimental design, data collection, and analysis. M.B.C. and K.E.V.: contributed to data collection.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201407-1262OC on October 17, 2014

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Javaheri S, Dempsey JA. Central sleep apnea. Compr Physiol. 2013;3:141–163. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowes G, Townsend ER, Kozar LF, Bromley SM, Phillipson EA. Effect of carotid body denervation on arousal response to hypoxia in sleeping dogs. J Appl Physiol. 1981;51:40–45. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1981.51.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillipson EA, Kozar LF, Rebuck AS, Murphy E. Ventilatory and waking responses to CO2 in sleeping dogs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977;115:251–259. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1977.115.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dempsey JA, Smith CA, Blain GM, Xie A, Gong Y, Teodorescu M. Role of central/peripheral chemoreceptors and their interdependence in the pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;758:343–349. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-4584-1_46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaur S, Pedersen NP, Yokota S, Hur EE, Fuller PM, Lazarus M, Chamberlin NL, Saper CB. Glutamatergic signaling from the parabrachial nucleus plays a critical role in hypercapnic arousal. J Neurosci. 2013;33:7627–7640. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0173-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gleeson K, Zwillich CW, White DP. The influence of increasing ventilatory effort on arousal from sleep. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:295–300. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guyenet PG, Stornetta RL, Bochorishvili G, Depuy SD, Burke PG, Abbott SB. C1 neurons: the body’s EMTs. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;305:R187–R204. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00054.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guyenet PG, Stornetta RL, Bayliss DA. Central respiratory chemoreception. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:3883–3906. doi: 10.1002/cne.22435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang S, Shi Y, Shu S, Guyenet PG, Bayliss DA. Phox2b-expressing retrotrapezoid neurons are intrinsically responsive to H+ and CO2. J Neurosci. 2013;33:7756–7761. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5550-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang S, Benamer N, Zanella S, Kumar NN, Shi Y, Bévengut M, Penton D, Guyenet PG, Lesage F, Gestreau C, et al. TASK-2 channels contribute to pH sensitivity of retrotrapezoid nucleus chemoreceptor neurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33:16033–16044. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2451-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li A, Nattie EE. Focal central chemoreceptor sensitivity in the RTN studied with a CO2 diffusion pipette in vivo. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1997;83:420–428. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun MK, Reis DJ. Hypoxia selectively excites vasomotor neurons of rostral ventrolateral medulla in rats. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:R245–R256. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.1.R245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun MK. Pharmacology of reticulospinal vasomotor neurons in cardiovascular regulation. Pharmacol Rev. 1996;48:465–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erickson JT, Millhorn DE. Hypoxia and electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus nerve induce Fos-like immunoreactivity within catecholaminergic and serotoninergic neurons of the rat brainstem. J Comp Neurol. 1994;348:161–182. doi: 10.1002/cne.903480202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbott SBG, Coates MB, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. Optogenetic stimulation of c1 and retrotrapezoid nucleus neurons causes sleep state-dependent cardiorespiratory stimulation and arousal in rats. Hypertension. 2013;61:835–841. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbott SBG, Stornetta RL, Fortuna MG, Depuy SD, West GH, Harris TE, Guyenet PG. Photostimulation of retrotrapezoid nucleus phox2b-expressing neurons in vivo produces long-lasting activation of breathing in rats. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5806–5819. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1106-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang DY, Carlezon WA, Jr, Isacson O, Kim KS. A high-efficiency synthetic promoter that drives transgene expression selectively in noradrenergic neurons. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:1731–1740. doi: 10.1089/104303401750476230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stornetta RL, Moreira TS, Takakura AC, Kang BJ, Chang DA, West GH, Brunet JF, Mulkey DK, Bayliss DA, Guyenet PG. Expression of Phox2b by brainstem neurons involved in chemosensory integration in the adult rat. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10305–10314. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2917-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter ME, Yizhar O, Chikahisa S, Nguyen H, Adamantidis A, Nishino S, Deisseroth K, de Lecea L. Tuning arousal with optogenetic modulation of locus coeruleus neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1526–1533. doi: 10.1038/nn.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreira TS, Takakura AC, Colombari E, Guyenet PG. Central chemoreceptors and sympathetic vasomotor outflow. J Physiol. 2006;577:369–386. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.115600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reis DJ, Ruggiero DA, Morrison SF. The C1 area of the rostral ventrolateral medulla oblongata. A critical brainstem region for control of resting and reflex integration of arterial pressure. Am J Hypertens. 1989;2:363S–374S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nattie E. Julius H. Comroe, Jr., distinguished lecture: central chemoreception: then ... and now. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2011;110:1–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01061.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abbott SB, DePuy SD, Nguyen T, Coates MB, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. Selective optogenetic activation of rostral ventrolateral medullary catecholaminergic neurons produces cardiorespiratory stimulation in conscious mice. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3164–3177. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1046-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holloway BB, Stornetta RL, Bochorishvili G, Erisir A, Viar KE, Guyenet PG. Monosynaptic glutamatergic activation of locus coeruleus and other lower brainstem noradrenergic neurons by the C1 cells in mice. J Neurosci. 2013;33:18792–18805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2916-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abbott SB, Kanbar R, Bochorishvili G, Coates MB, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. C1 neurons excite locus coeruleus and A5 noradrenergic neurons along with sympathetic outflow in rats. J Physiol. 2012;590:2897–2915. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.232157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Witten IB, Steinberg EE, Lee SY, Davidson TJ, Zalocusky KA, Brodsky M, Yizhar O, Cho SL, Gong S, Ramakrishnan C, et al. Recombinase-driver rat lines: tools, techniques, and optogenetic application to dopamine-mediated reinforcement. Neuron. 2011;72:721–733. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DePuy SD, Stornetta RL, Bochorishvili G, Deisseroth K, Witten I, Coates M, Guyenet PG. Glutamatergic neurotransmission between the C1 neurons and the parasympathetic preganglionic neurons of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. J Neurosci. 2013;33:1486–1497. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4269-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schreihofer AM, Guyenet PG. Identification of C1 presympathetic neurons in rat rostral ventrolateral medulla by juxtacellular labeling in vivo. J Comp Neurol. 1997;387:524–536. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971103)387:4<524::aid-cne4>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abbott SB, Holloway BB, Viar KE, Guyenet PG. Vesicular glutamate transporter 2 is required for the respiratory and parasympathetic activation produced by optogenetic stimulation of catecholaminergic neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla of mice in vivo. Eur J Neurosci. 2014;39:98–106. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guyenet PG, Mulkey DK, Stornetta RL, Bayliss DA. Regulation of ventral surface chemoreceptors by the central respiratory pattern generator. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8938–8947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2415-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reis DJ, Morrison S, Ruggiero DA. The C1 area of the brainstem in tonic and reflex control of blood pressure. State of the art lecture. Hypertension. 1988;11:I8–I13. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.11.2_pt_2.i8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMullan S, Pilowsky PM. The effects of baroreceptor stimulation on central respiratory drive: a review. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;174:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillipson EA, Sullivan CE, Read DJ, Murphy E, Kozar LF. Ventilatory and waking responses to hypoxia in sleeping dogs. J Appl Physiol. 1978;44:512–520. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1978.44.4.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phillips JK, Goodchild AK, Dubey R, Sesiashvili E, Takeda M, Chalmers J, Pilowsky PM, Lipski J. Differential expression of catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes in the rat ventrolateral medulla. J Comp Neurol. 2001;432:20–34. doi: 10.1002/cne.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross CA, Ruggiero DA, Joh TH, Park DH, Reis DJ. Rostral ventrolateral medulla: selective projections to the thoracic autonomic cell column from the region containing C1 adrenaline neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1984;228:168–185. doi: 10.1002/cne.902280204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hokfelt T, Fuxe K, Goldstein M, Johansson O. Immunohistochemical evidence for the existence of adrenaline neurons in the rat brain. Brain Res. 1974;66:235–251. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tucker DC, Saper CB, Ruggiero DA, Reis DJ. Organization of central adrenergic pathways: I. Relationships of ventrolateral medullary projections to the hypothalamus and spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1987;259:591–603. doi: 10.1002/cne.902590408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haselton JR, Guyenet PG. Ascending collaterals of medullary barosensitive neurons and C1 cells in rats. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:R1051–R1063. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.258.4.R1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun MK, Guyenet PG. GABA-mediated baroreceptor inhibition of reticulospinal neurons. Am J Physiol. 1985;249:R672–R680. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1985.249.6.R672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang F, Wang LP, Boyden ES, Deisseroth K. Channelrhodopsin-2 and optical control of excitable cells. Nat Methods. 2006;3:785–792. doi: 10.1038/nmeth936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kanbar R, Stornetta RL, Cash DR, Lewis SJ, Guyenet PG. Photostimulation of Phox2b medullary neurons activates cardiorespiratory function in conscious rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1184–1194. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0047OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marina N, Abdala AP, Korsak A, Simms AE, Allen AM, Paton JF, Gourine AV. Control of sympathetic vasomotor tone by catecholaminergic C1 neurones of the rostral ventrolateral medulla oblongata. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;91:703–710. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun MK, Reis DJ. Medullary vasomotor activity and hypoxic sympathoexcitation in pentobarbital-anesthetized rats. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:R348–R355. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.2.R348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abbott SB, Stornetta RL, Coates MB, Guyenet PG. Phox2b-expressing neurons of the parafacial region regulate breathing rate, inspiration, and expiration in conscious rats. J Neurosci. 2011;31:16410–16422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3280-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marina N, Abdala AP, Trapp S, Li A, Nattie EE, Hewinson J, Smith JC, Paton JF, Gourine AV. Essential role of Phox2b-expressing ventrolateral brainstem neurons in the chemosensory control of inspiration and expiration. J Neurosci. 2010;30:12466–12473. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3141-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Card JP, Sved JC, Craig B, Raizada M, Vazquez J, Sved AF. Efferent projections of rat rostroventrolateral medulla C1 catecholamine neurons: Implications for the central control of cardiovascular regulation. J Comp Neurol. 2006;499:840–859. doi: 10.1002/cne.21140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuwaki T, Zhang W. Orexin neurons as arousal-associated modulators of central cardiorespiratory regulation. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;174:43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chamberlin NL. Functional organization of the parabrachial complex and intertrigeminal region in the control of breathing. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2004;143:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Monnier A, Alheid GF, McCrimmon DR. Defining ventral medullary respiratory compartments with a glutamate receptor agonist in the rat. J Physiol. 2003;548:859–874. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.038141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith JC, Abdala AP, Borgmann A, Rybak IA, Paton JF. Brainstem respiratory networks: building blocks and microcircuits. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bell HJ, Ferguson C, Kehoe V, Haouzi P. Hypocapnia increases the prevalence of hypoxia-induced augmented breaths. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R334–R344. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90680.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Viemari JC, Garcia AJ, III, Doi A, Elsen G, Ramirez JM. β-Noradrenergic receptor activation specifically modulates the generation of sighs in vivo and in vitro. Front Neural Circuits. 2013;7:179. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guyenet PG, Abbott SB. Chemoreception and asphyxia-induced arousal. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013;188:333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Activity of norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats anticipates fluctuations in the sleep-waking cycle. J Neurosci. 1981;1:876–886. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00876.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee MG, Hassani OK, Jones BE. Discharge of identified orexin/hypocretin neurons across the sleep-waking cycle. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6716–6720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1887-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jacobs BL, Fornal CA. Activity of serotonergic neurons in behaving animals. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21(2) Suppl:9S–15S. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stettner GM, Lei Y, Benincasa Herr K, Kubin L. Evidence that adrenergic ventrolateral medullary cells are activated whereas precerebellar lateral reticular nucleus neurons are suppressed during REM sleep. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e62410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Benarroch EE, Smithson IL, Low PA, Parisi JE. Depletion of catecholaminergic neurons of the rostral ventrolateral medulla in multiple systems atrophy with autonomic failure. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:156–163. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rudzinski E, Kapur RP. PHOX2B immunolocalization of the candidate human retrotrapezoid nucleus. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2010;13:291–299. doi: 10.2350/09-07-0682-OA.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]