Abstract

AIM: To investigate the prognostic significance of lymph node micrometastasis (LNMM) in patients with gastric carcinoma.

METHODS: Two reviewers independently searched electronic databases including PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Cochrane Controlled Studies Register, and the China National Knowledge Infrastructure electronic database between January 1996 and January 2014. Strict literature retrieval and data extraction were performed to extract relevant data. Data analysis was conducted using RevMan 5.2.4 software, and relative risks (RRs) for patient death in five years and recurrence were calculated. A fixed- or random-effects model was selected to pool and a forest plot was used to display RRs.

RESULTS: Twelve cohort studies containing a total of 1684 patients were identified. LNMM positivity was worse than LNMM negativity with regards to the number of patients who died in five years. The effects of LNMM positivity in patients with gastric cancer of different T-stages remain unclear. LNMM in patients with gastric carcinoma was also associated with a higher recurrence rate. With regards to the number of patients who died in five years, Asian patients were worse than European and Australian patients.

CONCLUSION: We recommend that LNMM should not be used as a gold standard for prognosis evaluation in patients with gastric cancer in clinical settings until more high quality trials are available.

Keywords: Gastric carcinoma, Survival, Lymph node micrometastasis, Meta-analysis

Core tip: This is the first meta-analysis describing the effect of lymph node micrometastasis (LNMM) on gastric carcinoma prognosis worldwide. LNMM positivity was associated with a worse prognosis compared with LNMM negativity. The effects of LNMM positivity in patients with gastric cancer of different T-stages remain unclear. LNMM in patients with gastric carcinoma was also associated with a higher recurrence rate. With regards to the number of patients who died in five years, Asian patients were worse than European and Australian patients.

INTRODUCTION

Although gastric cancer has demonstrated the second largest annual decline in death rates over the past 10 years (2000-2009), it remains the second highest cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with a total of 21600 new cases and 10990 deaths projected to occur in the United States in 2013[1,2]. Although systematic lymph node dissection is performed routinely for patients with gastric cancer and has improved survival rates, some patients still die of recurrence. Lymph node metastasis is considered one of the most significant prognostic parameters in patients with gastric carcinoma[3-8]. However, several researchers have demonstrated that radical gastrectomy with lymph node dissection leading to a node-negative (pN0) final diagnosis based on hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining did not prevent gastric cancer recurrence[9-11]. Lymph node micrometastasis (LNMM; 0.2-2.0 mm in size), which is common in nodes deemed to be negative by HE staining, but positive for cytokeratin (CK) by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining, is thought to be a key etiology of recurrence and distant metastasis after resection of primary gastric tumors[12]. Recently, IHC techniques have been applied to identify lymph node micrometastasis missed by routine histological examination. However, the clinical impact of LNMM on gastric carcinoma prognosis remains controversial[13-17]. Several studies have reported that LNMM missed by HE staining in gastric carcinoma is a strong indicator of overt metastatic disease or poor prognosis; some researchers reported that there is no significant correlation between micrometastasis and other clinicopathologic characteristics, and that the presence of LNMM does not influence patient prognosis[18-29]. Thus, we aimed to investigate the potential prognostic significance of LNMM in patients with gastric cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

To identify relevant studies and published abstracts, PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Cochrane Controlled Studies Register, and the China National Knowledge Infrastructure electronic databases were searched systematically between January 1996 and January 2014. Medical subject headings of “gastric carcinoma/cancer,” “lymph node micrometastasis,” and “prognosis” were used. The reference lists of all retrieved articles were reviewed for further identification of potentially relevant studies.

Data collection process

Two reviewers (Zeng YJ, Zhang CD) independently extracted relevant data, including study and population features and outcomes from key words, titles, abstracts, and full articles when necessary. They compared the results, synthesized the same opinions, and solved disagreements by discussion with a third reviewer.

The following data were extracted for all included studies: treatment approach, study and year, country, depth of tumor invasion, median age or mean age, sex ratio, median follow-up, method of detecting LNMM, definition of micrometastasis, average numbers of lymph nodes retrieved, journal name, sample size, number of patients who died in five years, and recurrence rate (Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the studies included

| Ref. | Country | Sex (male/female) | Age (yr) | Median follow-up |

| Cai et al[18], 2000 | Japan | 52/272 | 63 mea | 24 M |

| Fukagawa et al[19], 2001 | Japan | 51/18 vs 22/163 | 57.8 ± 10.8 vs 59.8 ± 12.11 med | > 36 M |

| Choi et al[20], 2002 | South Korea | 37/23 vs 19/93 | 59 mea | 26.3 vs 25.13 |

| Lee et al[21], 2002 | Australia | NM | NM | NM |

| Yasuda et al[22], 2002 | Japan | 30/14 vs 13/73 | NM | > 60 M |

| Morgagni et al[23], 2003 | Italy | 111/119 | 68 med | 60 M |

| Yonemura et al[24], 2007 | Japan | 198/110 | NM | 83 M |

| Kim et al[25], 2008 | South Korea | 110/43 vs 21/103 | 54.7 ± 10.8 vs 52.0 ± 12.51 med | 83 M |

| Ishii et al[26], 2008 | Japan | 23/12 | 62 med | 57.1 M |

| Kim et al[27], 2009 | South Korea | 50/40 | 55.1 ± 12.2 vs 51.6 ± 12.31 mea | 49 vs 47 M3 |

| Wang et al[28], 2012 | China | 43/22 vs 74/523 | 31.8 ± 10.9 vs 57.9 ± 13.01 mea | 45.6 M |

| Jeuck et al[29], 2015 | Germany | 51/13 vs 28/33 | 66.3 mea | 56.4 vs 49.23 |

mean ± SD;

There are a total of 79 patients in this study and 10 patients were excluded because they suffered metastasis;

Lymph node micrometastasis (LNMM) negative vs positive. med: Median age; mea: Mean age; NM: Not mentioned.

Table 2.

Lymph node micrometastasis characteristics of the included studies

| Ref. | Depth of tumor invasion | Method | Antibody | Definition of micrometastasis | LNs (n) | Average LNs (n) |

| Cai et al[18], 2000 | T1b | IHC | CK (CAM5.2) | pN0 by HE staining | 1945 | 25.0 |

| Fukagawa et al[19], 2001 | T2-T3 | IHC | CK (AE1/AE3) | pN0 by HE staining | 4484 | 41.9 |

| Choi et al[20], 2002 | T1b | IHC | CK (AE1/AE3) | pN0 by HE staining | 2272 | 25.8 |

| Lee et al[21], 2002 | T1-T4 | IHC | CK (35βH11) | pN0 by HE staining | 3625 | 23.7 |

| Yasuda et al[22], 2002 | T2-T3 | IHC | CK (CAM5.2) | pN0 by HE staining | 2039 | 31.9 |

| Morgagni et al[23], 2003 | T1 | IHC | CK(MNF 116) | pN0 by HE staining | 5400 | 18.0 |

| Yonemura et al[24], 2007 | T1-T4 | IHC | CK (AE1/AE3) | ≤ 0.2 mm | 12012 | 39.0 |

| Kim et al[25], 2008 | T1-T3 | IHC | CK (AE1/AE3) | pN0 by HE staining | 4990 | 27.1 |

| Ishii et al[26], 2008 | T1b-T2 | IHC | CK (O.N.352) | pN0 by HE staining | 1028 | 29.4 |

| Kim et al[27], 2009 | T1 | IHC | CK (AE1/AE3) | ≤ 2 mm | 3526 | 39.2 |

| Wang et al[28], 2011 | T1-T3 | IHC | CK (AE1/AE3) | > 0.2 mm and ≤ 2 mm | 4202 | 22.0 |

| Jeuck et al[29], 2015 | T1-T4 | IHC | CK (KL1) | pN0 by HE staining | 2018 | 21.2 |

IHC: Inmmunohistochemistry; CK: Cytokeratin; pN0: Node-negative; HE: Hematoxyline-eosin; T1: Tumor invades lamina propria, muscularis mucosae or submucosa; T1a: Tumor invades lamina propria or muscularis mucosae; T1b: Tumor invades submucosa; T2: Tumor invades muscularis propria; T3: Tumor penetrates subserosal connective tissue without invasion of visceral peritoneum or adjacent structures; T4a: Tumor invades serosa (visceral peritoneum); T4b: Tumor invades adjacent structures.

Table 3.

Lymph node micrometastasis positive vs negative groups

| Ref. | Sample (positive vs negative) | Patients who died in 5 yr (positive vs negative) | P value |

| Cai et al[18], 2000 | 69 (17 vs 52) | 3/17 vs 0/52 | < 0.01 |

| Fukagawa et al[19], 2001 | 107 (38 vs 69) | 2/38 vs 8/69 | 0.860 |

| Choi et al[20], 2002 | 88 (28 vs 60) | 2/28 vs 3/60 | 0.683 |

| Lee et al[21], 2002 | 153 (75 vs 78) | Total: 38/75 vs 19/78; EGC: 2/12 vs 0/34; AGC: 36/63 vs 19/44 | < 0.05 |

| Yasuda et al[22], 2002 | 64 (20 vs 44) | 7/20 vs 2/44 | < 0.1 |

| Morgagni et al[23], 2003 | 300 (30 vs 270) | 2/30 vs 30/270 | 0.779 |

| Yonemura et al[24], 2007 | 308 (37 vs 271) | 5/37 vs 16/271 | 0.014 |

| Kim et al[25], 2008 | 184 (31 vs 153) | 13/31 vs 13/1531 | < 0.001 |

| Ishii et al[26], 2008 | 35 (4 vs 31) | - | - |

| Kim et al[27], 2009 | 90 (9 vs 81) | 0/9 vs 0/812 | - |

| Wang et al[28], 2011 | 191 (54 vs 137) | 39/54 vs 18/137 | < 0.001 |

| Jeuck et al[29], 2014 | 95 (16 vs 79) | 6/16 vs 21/79 | 0.026 |

Median survival 17 mo, 95%CI: 7-28 for micrometastasis positive, and median survival not reached, 95%CI: 6-121 mo for micrometastasis negative;

Disease-specific survival. EGC: Early gastric cancer; AGC: Advanced gastric cancer.

Table 4.

Recurrence rates for lymph node micrometastasis positive vs negative groups

| First author, year | Recurrence (positive vs negative) |

| Cai et al[18], 2000 | 3/17 vs 0/52 |

| Fukagawa et al[19], 2001 | 2/38 vs 4/65 |

| Choi et al[20], 2002 | 2/28 vs 3/60 |

| Morgagni et al[23], 2002 | 2/30 vs 0/270 |

| Yonemura et al[24], 2007 | 5/37 vs 1/271 |

| Kim et al[25], 2008 | 12/31 vs 5/153 |

| Ishii et al[26], 2008 | 0/4 vs 0/31 |

| Kim et al[27], 2008 | 0/9 vs 0/211 |

Disease-specific survival.

Inclusion criteria

Based on the Cochrane handbook for systematic review of interventions (Version 5.2.4), inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria were designed. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) all published and unpublished high quality original studies; (2) only studies discussing the clinical impact of LNMM on prognosis of gastric carcinoma were included; (3) only the most informative and latest study from the same author or institution was selected; and (4) retrieval of at least 15 lymph nodes to avoid stage migration was considered the minimum number of lymph nodes necessary for accurate staging of gastric cancer, according to NCCN Guidelines Version 2.2013 Gastric cancer[30,31]. No restriction on language was considered.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) less than the minimum number of lymph nodes (n = 15) retrieved[30,31]; (2) low quality studies or those with little information about the data of interest; and (3) non-cohort studies, reviews, or case reports.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were conducted using Review Manager 5.2.4 software. Dichotomous variables were analyzed with relative risks (RRs). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant; a 95%CI was applied. A fixed-effects model was selected if I2 was ≤ 30% and the P value for a test of heterogeneity was ≥ 0.05. A random-effects model was selected if I2 was >3 0% and the P value for a test of heterogeneity was < 0.1.

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from randomization to death from any cause or to the last follow-up visit[32]. When there was no randomization in cohort studies analyzed, we used the number of patients who died in five years to evaluate patients’ survival in this meta-analysis, rather than OS.

RESULTS

The primary section of this meta-analysis concerns LNMM positivity vs LNMM negativity. The second section addresses the numbers of patients who died in five years in LNMM positive and LNMM negative groups. In the third section, recurrence rates in both groups are addressed. A forest plot was conducted to display RRs and subgroup analyses when applied. In addition, funnel plots and Egger’s test were used to assess publication bias.

A total of 83 studies were retrieved and 71 of them were found to be unrelated to our study. As a result, 12 cohort studies involving 1684 patients were finally included[18-29]. Eleven studies addressed survival rates in LNMM positive and negative gastric carcinoma cases, for a total of 1649 patients[18-29]. Four studies[20,21,23,27] addressed the numbers of patients who died in five years for LNMM positive and negative groups of patients with early gastric carcinoma. Eight studies[18,20,23-27] compared preoperative recurrence in LNMM positive and negative groups. Included studies are described in Tables 1-4.

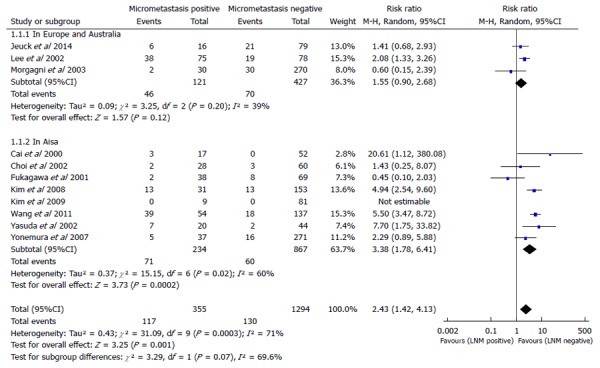

Numbers of gastric cancer patients who died in five years, LNMM positive vs negative groups

In this meta-analysis, we used the number of patients who died in five years to evaluate patient survival. A subgroup analysis between Asia, Europe, and Australia was conducted for a total of 11 studies containing 1649 patients (355 LNMM positive, 1294 LNMM negative) and a random-effects model was used (total: I2 = 71%, heterogeneity test P = 0.0003). There was a significant difference between LNMM positive and negative groups in the number of patients who died in five years in Asia, and the RR was 3.38 (1.78-6.41, P = 0.0002). On the contrary, the RR for patient death in five years in Europe and Australia was 1.55 (0.90-2.68, P = 0.12), and the number of patients who died in five years demonstrated no significant difference between LNMM positive and negative groups. In addition, the RR for total events was 2.43 (1.42-4.13, P = 0.001; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Meta-analysis examining patients who died in five years for lymph node micrometastasis positive vs negative groups. LNM: Lymph node metastasis.

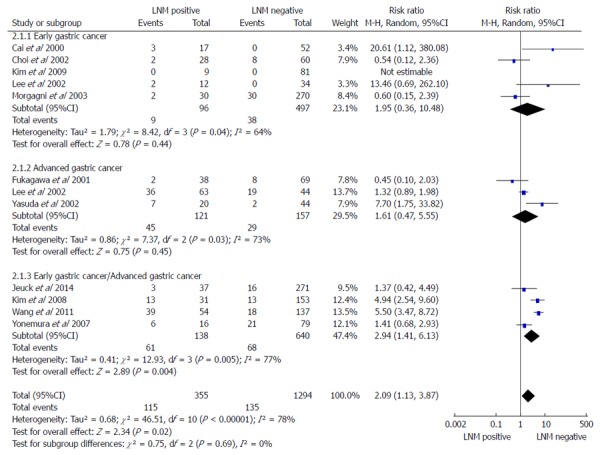

Numbers of gastric cancer patients who died in five years in early, advanced, and early/advanced gastric cancer, LNMM positive vs LNMM negative groups

A subgroup analysis in early gastric cancer (EGC), advanced gastric cancer (AGC), and EGC/AGC was conducted, with a total of 11 studies containing 1649 patients (355 LNMM positive, 1294 LNMM negative). A random-effects model analysis was conducted (total: I2 = 78%, heterogeneity test P < 0.00001). For EGC, five cohort studies[18,20,21,23,27] were included (105 LNMM positive, 535 LNMM negative) and a random-effects model was applied (I2 = 64%, heterogeneity test P = 0.04). No statistically significant difference was found with regards to the number of patients who died in five years in patients with LNMM positivity compared with LNMM negativity in EGC (RR = 1.95, 95%CI: 0.36-10.48, P = 0.44). For AGC, three cohort studies[19,21,22] were included (166 LNMM positive, 186 LNMM negative) and a random-effects model was applied (I2 = 73%, heterogeneity test P = 0.03). No statistically significant difference in the number of patients who died in five years was found in patients with LNMM positivity compared with LNMM negativity in AGC (RR = 1.61, 95%CI: 0.47-5.55, P = 0.45). On the contrary, the RR for patient death in five years in the EGC/AGC group was 2.94 (1.41-6.13, P = 0.004), and the number of patients who died in five years demonstrated statistical significance. In addition, the RR for total events was 2.09 (1.13-3.87, P = 0.02; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis examining patients who died in five years for lymph node micrometastasis positive vs negative groups in patients with early gastric cancer, advanced gastric cancer, and early/advanced gastric cancer. LNM: Lymph node metastasis.

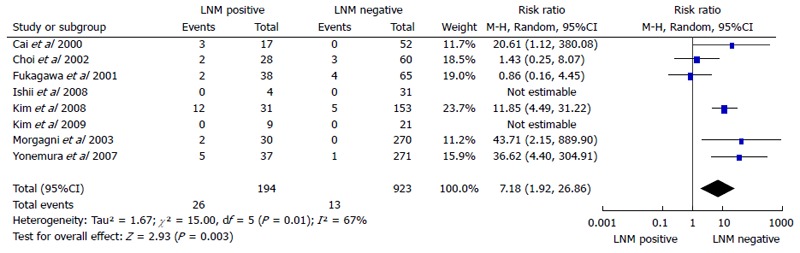

Gastric cancer recurrence rates for LNMM positive and LNMM negative groups

Eight cohort studies[18-20,23-27] containing 1117 patients (194 LNMM positive, 923 LNMM negative) were included. A significant difference was observed with regards to recurrence rate (RR = 7.18, 95%CI: 1.92-26.86, P = 0.003). Statistical heterogeneity was detected (I2 = 67%, heterogeneity test P = 0.01; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of recurrence rates for lymph node micrometastasis positive vs negative groups in gastric cancer. LNM: Lymph node metastasis.

DISCUSSION

Most of the included cohort trials conducted between 1996 and 2014 had small statistical power in this meta-analysis. Meta-analysis is an ideal statistical tool that increases the statistical power of comparisons, and offers more powerful evidence for clinical decision making compared with cohort trials. Thus, this meta-analysis was conducted to assess the clinical impact of LNMM on gastric carcinoma prognosis. LNMM (0.2-2.0 mm in size), which is common in nodes deemed to be negative by HE staining, but positive for CK by IHC staining, is thought to be a key etiology of recurrence and distant metastasis after resection of primary gastric tumors[12]. Recently, IHC techniques have been applied to identify LNMM missed by routine histological examination. However, the clinical impact of lLNMM on gastric carcinoma prognosis remains controversial[13-17].

In this meta-analysis, we used the number of patients who died in five years to evaluate patient survival. LNMM positivity was associated with a worse prognosis compared with LNMM negativity. LNMM in patients with gastric carcinoma was also associated with a higher recurrence rate. The number of patients who died in five years was worse for Asian, compared with European and Australian patients.

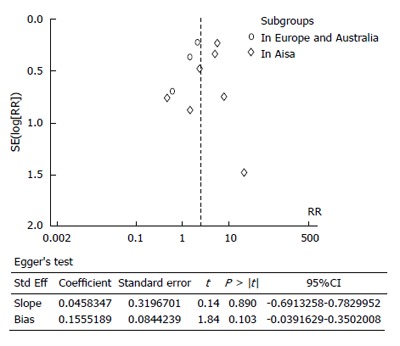

It is relatively more difficult to achieve the minimum number of retrieved lymph nodes in patients in the West compared with patients in the East, as the former tends to have a larger BMI. We found a higher number of retrieved lymph nodes in studies from Eastern Asia (average 22-41.9) compared with the Italian, German, and Australian (average 18-23.7) counterparts. Considering the fact that the average number of retrieved lymph nodes was more than 15, but fewer than 15 lymph nodes were retrieved in individual patients, it was more likely that an inexperienced pathologist could have failed to identify micrometastases. We concluded that studies in which a higher number of lymph nodes were retrieved would have more reliable results. The fewer number of retrieved lymph nodes in Italian, German, and Australian studies, compared with those from Eastern Asia, could lead to a more obscure relationship between LNMM positivity and the number of patients who died in five years in the Europe and Australia subgroup analysis, where no significant difference between groups was found. Additionally, only three cohort trials were utilized in Europe and Australia, resulting in possible publication bias (Figure 4). The total number of patients from three cohort trials in Europe and Australia group was 528, without randomization in cohort studies, all of which could affect the numbers of patients who died in five years for Asia and Europe/Australia. We speculate that, with regards to the number of patients who died in five years, LNMM positivity is worse in Asian patients, and that the effects of LNMM positivity on survival in Europe/Australia patients still require validation until more high-level cohort studies are available.

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of patients who died in five years in patients with positive vs negative lymph node micrometastasis and Egger’s test for publication bias for patients who died in five years for lymph node micrometastasis positive vs negative groups.

Gastric carcinoma prognosis is strongly affected by the T-stage of the tumor. Peritoneal dissemination and subsequent peritoneal recurrence are common when the primary tumor invades through the serosa (T3)[19]. The available evidence from the 11 trials showed that neither the EGC only group nor the AGC only group had a significant difference in the number of patients who died in five years between LNMM positive and negative groups. On the contrary, the EGC/AGC group showed a significant difference between groups with regards to the number of patients who died in five years. This finding is the opposite of that found in several previous studies[18,21,22,25,28,29]. However, the total numbers of patients in the EGC, AGC, and EGC/AGC groups were 640, 352, and 907, respectively. It is more likely that these three groups (EGC[18,20,21,27], AGC[19,21,22] and EGC/AGC[24,25,28,29]) were insufficiently powered. Therefore, the effects of LNMM positivity in different T-stages of gastric cancer remain unclear and require validation in future studies.

We found no difference in the number of patients who died in five years in EGC, which may be because no further LNM or LNMM was detected in EGC due to its early pathological stage, or because of insufficiently powered results. Likewise, we found that no difference in the number of patients who died in five years in the AGC group; however, there was a significant difference in the EGC/AGC group. In light of these considerations, we recommend that LNMM should not be used as a gold standard for prognosis evaluation in patients with gastric cancer until more high quality trials are available.

It has been widely accepted that cancer relapse may originate from micrometastatic lesions with proliferative activity[24]. Previous studies reported that LNMM was strongly associated with the subsequent development of hematogenous and peritoneal metastases, but not locoregional lymph node recurrence[9,18,33]. Likewise, the available evidence from eight cohort studies supports the likelihood of recurrence in LNMM positive compared with LNMM negative patients.

The limitations of these studies require attention, including: (1) unsatisfied statistical power; (2) significant heterogeneity among studies in some comparisons, which requires subgroup analyses to exclude potential difference; and (3) a relatively symmetrical funnel plot for the numbers of patients who died in five years in LNMM positive compared with LNMM negative patients (5 dots on the left and 4 dots on the right). Stata version 12.0 was used (Egger’s test) to assess publication bias, and a relatively small publication bias was detected (P = 0.103; Figure 4). There was no country or language restriction used in this meta-analysis.

Based on the present evidence, our meta-analysis indicates that LNMM may be associated with higher recurrence rates in Asian gastric cancer patients, with higher numbers of patients who died in five years. However, due to unsatisfied statistical power, there is no definite evidence for higher numbers of patients who died in five years associated with LNMM positivity in the subgroup analysis for EGC or AGC only. Therefore, we recommend that LNMM should not be used as a gold standard for prognosis evaluation in patients with gastric cancer until more high quality trials are available.

COMMENTS

Background

Gastric cancer remains the second highest cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide. Several studies have reported that lymph node micrometastasis missed by hematoxylin-eosin staining in gastric carcinoma is a strong indicator of overt metastatic disease or poor prognosis; some researchers reported that there is no significant correlation between micrometastasis and other clinicopathologic characteristics, and that the presence of lymph node micrometastasis does not influence patient prognosis.

Research frontiers

To date, many studies have been performed to determine the association between lymph node micrometastasis (LNMM) and gastric cancer prognosis, including several recent systematic reviews. However, these reviews were methodologically insufficient and thus could not achieve a comprehensive conclusion.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Based on the present evidence, our meta-analysis indicates that LNMM may be associated with higher recurrence rates in Asian gastric cancer patients, and higher numbers of patients who died in five years. However, there was no strong evidence that LNMM was associated with a worse prognosis in gastric cancer patients in the West. These findings were not presented clearly in previous systematic reviews.

Applications

LNMM may be associated with higher recurrence rates in Asian gastric cancer patients, with higher numbers of patients who died in five years, but had no significant effect on prognosis of patients in the West. An exploration of the mechanism for this association may help to improve gastric cancer prognosis.

Terminology

LNMM (0.2-2.0 mm in size), which is common in nodes deemed to be negative by HE staining, but positive for cytokeratin by immunohistochemical staining, is thought to be a key etiology of recurrence and distant metastasis after resection of primary gastric tumors.

Peer-review

The present manuscript addresses lymph node micrometastasis, a very controversial topic in gastric cancer treatment. It is well known that survival in N0 patients improves as a function of the number of retrieved nodes.

Footnotes

Supported by Grants from Liaoning Province Science and Technology Plan Project, No. 2013225021.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: May 4, 2014

First decision: June 18, 2014

Article in press: November 11, 2014

P- Reviewer: Verlato G S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2012: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012:Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.3322/caac.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bozzetti F, Bonfanti G, Morabito A, Bufalino R, Menotti V, Andreola S, Doci R, Gennari L. A multifactorial approach for the prognosis of patients with carcinoma of the stomach after curative resection. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1986;162:229–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mine M, Majima S, Harada M, Etani S. End results of gastrectomy for gastric cancer: effect of extensive lymph node dissection. Surgery. 1970;68:753–758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kodama Y, Sugimachi K, Soejima K, Matsusaka T, Inokuchi K. Evaluation of extensive lymph node dissection for carcinoma of the stomach. World J Surg. 1981;5:241–248. doi: 10.1007/BF01658301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otsuji E, Kuriu Y, Ichikawa D, Okamoto K, Hagiwara A, Yamagishi H. Tumor recurrence and its timing following curative resection of early gastric carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:3499–3503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoksch B, Müller JM. [Surgical management of locoregional recurrence of gastric carcinoma] Zentralbl Chir. 1999;124:1087–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohgaki M, Toshio T, Akeo H, Yamasaki J, Togawa T. Effect of extensive lymph node dissection on the survival of early gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:2096–2099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maehara Y, Oshiro T, Endo K, Baba H, Oda S, Ichiyoshi Y, Kohnoe S, Sugimachi K. Clinical significance of occult micrometastasis lymph nodes from patients with early gastric cancer who died of recurrence. Surgery. 1996;119:397–402. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(96)80138-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siewert JR, Kestlmeier R, Busch R, Böttcher K, Roder JD, Müller J, Fellbaum C, Höfler H. Benefits of D2 lymph node dissection for patients with gastric cancer and pN0 and pN1 lymph node metastases. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1144–1147. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800830836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishida K, Katsuyama T, Sugiyama A, Kawasaki S. Immunohistochemical evaluation of lymph node micrometastases from gastric carcinomas. Cancer. 1997;79:1069–1076. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970315)79:6<1069::aid-cncr3>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayashi N, Ito I, Yanagisawa A, Kato Y, Nakamori S, Imaoka S, Watanabe H, Ogawa M, Nakamura Y. Genetic diagnosis of lymph-node metastasis in colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1995;345:1257–1259. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90922-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutait R, Alves VA, Lopes LC, Cutait DE, Borges JL, Singer J, da Silva JH, Goffi FS. Restaging of colorectal cancer based on the identification of lymph node micrometastases through immunoperoxidase staining of CEA and cytokeratins. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:917–920. doi: 10.1007/BF02049708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenson JK, Isenhart CE, Rice R, Mojzisik C, Houchens D, Martin EW. Identification of occult micrometastases in pericolic lymph nodes of Duke’s B colorectal cancer patients using monoclonal antibodies against cytokeratin and CC49. Correlation with long-term survival. Cancer. 1994;73:563–569. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940201)73:3<563::aid-cncr2820730311>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeffers MD, O’Dowd GM, Mulcahy H, Stagg M, O’Donoghue DP, Toner M. The prognostic significance of immunohistochemically detected lymph node micrometastases in colorectal carcinoma. J Pathol. 1994;172:183–187. doi: 10.1002/path.1711720205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adell G, Boeryd B, Frånlund B, Sjödahl R, Håkansson L. Occurrence and prognostic importance of micrometastases in regional lymph nodes in Dukes’ B colorectal carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study. Eur J Surg. 1996;162:637–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oberg A, Stenling R, Tavelin B, Lindmark G. Are lymph node micrometastases of any clinical significance in Dukes Stages A and B colorectal cancer? Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1244–1249. doi: 10.1007/BF02258221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cai J, Ikeguchi M, Maeta M, Kaibara N. Micrometastasis in lymph nodes and microinvasion of the muscularis propria in primary lesions of submucosal gastric cancer. Surgery. 2000;127:32–39. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.100881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukagawa T, Sasako M, Mann GB, Sano T, Katai H, Maruyama K, Nakanishi Y, Shimoda T. Immunohistochemically detected micrometastases of the lymph nodes in patients with gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;92:753–760. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010815)92:4<753::aid-cncr1379>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi HJ, Kim YK, Kim YH, Kim SS, Hong SH. Occurrence and prognostic implications of micrometastases in lymph nodes from patients with submucosal gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:13–19. doi: 10.1245/aso.2002.9.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee E, Chae Y, Kim I, Choi J, Yeom B, Leong AS. Prognostic relevance of immunohistochemically detected lymph node micrometastasis in patients with gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:2867–2873. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yasuda K, Adachi Y, Shiraishi N, Inomata M, Takeuchi H, Kitano S. Prognostic effect of lymph node micrometastasis in patients with histologically node-negative gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:771–774. doi: 10.1007/BF02574499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morgagni P, Saragoni L, Scarpi E, Zattini PS, Zaccaroni A, Morgagni D, Bazzocchi F. Lymph node micrometastases in early gastric cancer and their impact on prognosis. World J Surg. 2003;27:558–561. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-6797-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yonemura Y, Endo Y, Hayashi I, Kawamura T, Yun HY, Bandou E. Proliferative activity of micrometastases in the lymph nodes of patients with gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2007;94:731–736. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JH, Park JM, Jung CW, Park SS, Kim SJ, Mok YJ, Kim CS, Chae YS, Bae JW. The significances of lymph node micrometastasis and its correlation with E-cadherin expression in pT1-T3N0 gastric adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:125–130. doi: 10.1002/jso.20937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishii K, Kinami S, Funaki K, Fujita H, Ninomiya I, Fushida S, Fujimura T, Nishimura G, Kayahara M. Detection of sentinel and non-sentinel lymph node micrometastases by complete serial sectioning and immunohistochemical analysis for gastric cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2008;27:7. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-27-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim JJ, Song KY, Hur H, Hur JI, Park SM, Park CH. Lymph node micrometastasis in node negative early gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Yu JC, Kang WM, Wang WZ, Liu YQ, Gu P. The predictive effect of cadherin-17 on lymph node micrometastasis in pN0 gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1529–1534. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeuck TL, Wittekind C. Gastric carcinoma: stage migration by immunohistochemically detected lymph node micrometastases. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:100–108. doi: 10.1007/s10120-014-0352-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hundahl SA, Phillips JL, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base Report on poor survival of U.S. gastric carcinoma patients treated with gastrectomy: Fifth Edition American Joint Committee on Cancer staging, proximal disease, and the “different disease” hypothesis. Cancer. 2000;88:921–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith DD, Schwarz RR, Schwarz RE. Impact of total lymph node count on staging and survival after gastrectomy for gastric cancer: data from a large US-population database. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7114–7124. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.14.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.GASTRIC (Global Advanced/Adjuvant Stomach Tumor Research International Collaboration) Group, Paoletti X, Oba K, Burzykowski T, Michiels S, Ohashi Y, Pignon JP, Rougier P, Sakamoto J, Sargent D, Sasako M, Van Cutsem E, Buyse M. Benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:1729–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Natsugoe S, Aikou T, Shimada M, Yoshinaka H, Takao S, Shimazu H, Matsushita Y. Occult lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer with submucosal invasion. Surg Today. 1994;24:870–875. doi: 10.1007/BF01651001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]