Abstract

It has been proposed, and only minimally explored, that personality factors may play a role in determining an individual's sensitivity to and preference for capsaicin containing foods. We explored these relationships further here. Participants rated a number of foods and sensations on a generalized liking scale in a laboratory setting; after leaving the laboratory, they filled out an online personality survey, which included Arnett's Inventory of Sensation Seeking (AISS) and the Sensitivity to Punishment-Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ). Recently, we reported strong and moderate correlations between the liking of a spicy meal and the personality constructs of Sensation Seeking (AISS) and Sensitivity to Reward (SPSRQ), respectively. Here, we use moderation models to explore the relationships between personality traits, perceived intensity of the burn of capsaicin, and the liking and consumption of spicy foods. Limited evidence of moderation was observed; however differential effects of the personality traits were seen in men versus women. In men, Sensitivity to Reward associated more strongly with liking and consumption of spicy foods, while in women, Sensation Seeking associated more strongly with liking and intake of spicy foods. These differences suggest that in men and women, there may be divergent mechanisms leading to the intake of spicy foods; specifically, men may respond more to extrinsic factors, while women may respond more to intrinsic factors.

Keywords: Arnett's Inventory of Sensation Seeking, capsaicin, food choice, moderation, Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward, individual differences

1. Introduction

It is well accepted that liking of a food drives intake (Cowart, 1981; Duffy, Hayes et al., 2009; Randall & Sanjur, 1981; Rozin & Zellner, 1985; Schutz, 1957). In the absence of economic and availability constraints, liking may be the single most important determinant of food choice in meals eaten both in and outside the home (Eertmans, Baeyens et al., 2001; IFIC, 2014). Healthfulness is the second most important criteria in determining food choice (IFIC, 2014). While capsaicin intake has been linked with a number of health benefits (Ludy & Mattes, 2011a; Ludy, Moore et al., 2012; Matsumoto, Miyawaki et al., 2000; Westerterp-Plantenga, Smeets et al., 2005; Yoshioka, Imanaga et al., 2004; Yoshioka, Lim et al., 1995; Yoshioka, St-Pierre et al., 1999), the burning and stinging sensation elicited by capsaicin can still serve as a strong deterrent against intake for some individuals. Assuming that an individual's affective response to oral burn is a major determinant in whether that individual will consume spicy foods, there is merit in exploring the factors that may cause some individuals but not others to enjoy burning sensations.

Factors that reportedly influence food liking include physiological differences such as taste phenotype (Duffy & Bartoshuk, 2000; Duffy, Lanier et al., 2007) or oral anatomy (Bartoshuk, 1993; Miller & Reedy, 1990), as well as prior exposure and familiarity with spicy foods (Logue & Smith, 1986; Ludy & Mattes, 2011b; Rozin & Schiller, 1980; Stevenson & Yeomans, 1993). Moreover, humans can learn to like the burn of capsaicin with repeated exposure (Rozin, 1990), and acute and chronic desensitization to capsaicin in and outside the laboratory are well-documented phenomena (Green & Hayes, 2003; Karrer & Bartoshuk, 1991; Lawless, Rozin et al., 1985; Stevenson & Prescott, 1994). Thus, it is conceivable that the higher usage levels typically observed among frequent chili users is due to greater tolerance to the burn (i.e. reduced burn intensity). However, Rozin and others have suggested that any effect of desensitization on liking of capsaicin is small, and that the affective shift from disliking to liking is attributable to other factors (Rozin & Rozin, 1981; Rozin & Schiller, 1980; Stevens, 1996).

Personality is also known to play a role in determining the liking of spicy foods. The liking of chili peppers and “unusual spices” has been linked with personality characteristics such as strength and daring and with thrill and adventure seeking behaviors (Rozin & Schiller, 1980; Stevens, 1996; Terasaki & Imada, 1988). Rozin and Schiller (1980) asked rural Mexican villagers (N=13) a number of questions about “hypothetical twins who were identical, except that one ate chili and the other did not” during interviews to explore possible social associations with chili consumption. These questions included “Which twin is stronger? Which twin is female? Which twin is less intelligent?” A majority of the respondents identified the twin that ate chili as being stronger, and they also indicated none of the other attributes could be determined just by knowing which twin consumed chili. Rozin and Schiller hypothesized this attribution of strength to chili eaters may be related to the Mexican idea of machismo, indicating that traits of daring and masculinity. No difference in the preference for spicy foods between men and women was found in the Mexican sample, possibly due to the prevalence of chili in the diet of the region. Later, Rozin reported enjoyment of certain activities, which he classified as masochistic, such as amusement park rides, dangerous sports, and gambling, were linked with the liking of chili peppers (Rozin, 1990). However, the link to sensation seeking was an inference based on a common theorized ‘constrained risk’ across these activities, as Rozin never directly associated measures of sensation seeking with chili liking or intake. Notably, since this work was conducted, use and consumption of capsaicin and chili peppers in the United States has risen substantially (Govindarajan & Sathyanarayana, 1991; Lucier, Pollack et al., 2006; Reinagel, 2012).

Elsewhere, personality measures used previously have been criticized for containing gender and age-biased items, as well as for the response style employed by the scales (Arnett, 1994; Haynes, Miles et al., 2000). Recently, we reported strong positive correlations between the personality variable Sensation Seeking, as measured with Arnett's Inventory of Sensation Seeking (AISS; Arnett, 1994), and the liking of some types of spicy food (Byrnes & Hayes, 2013). We also observed a more modest positive relationship between spicy food liking and the Sensitivity to Reward subscale of the English language version (O'Connor, Colder et al., 2004) of Torrubia and colleagues' Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ; Torrubia, Avila et al., 2001). These findings extend existing literature on the links between personality traits and orally irritating foods, by suggesting that multiple, distinct personality constructs may influence an individual's affective response to chili-containing foods. However, not all studies study support an association between personality and liking of spicy foods (e.g. Ludy & Mattes, 2012), but the failure to observe a relationship may be due to low power (small n) or measurement error inherent to brief measures of personality.

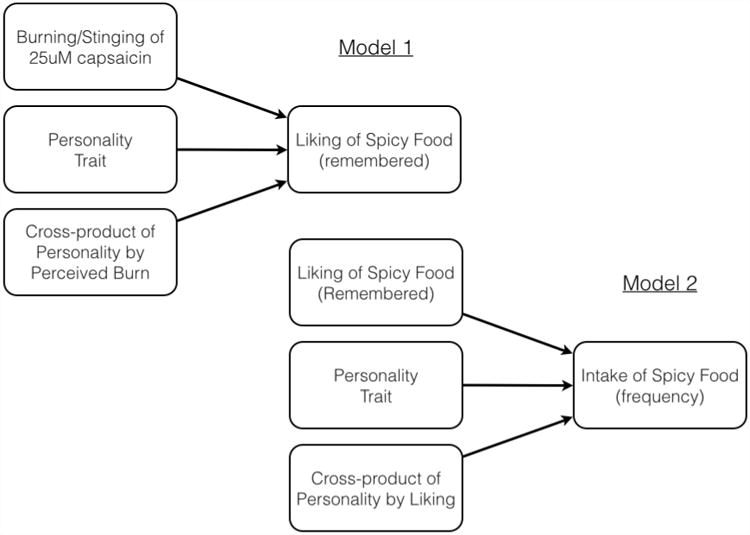

The original objective of the present work was to test the hypothesis that personality modifies the relationship between the perceived burn of capsaicin and the liking/disliking of spicy foods. To formally test this, we constructed a model to test whether personality moderates the relationship between capsaicin burn and spicy food liking, using standard guidelines established by Baron and Kenny (1986). In a moderation model, the outcome variable is regressed onto the predictor and moderator variables as well as onto a multiplicative interaction term of the predictor and the moderator. This interaction term is included in the model to test the influence of the putative moderator (here, personality trait) on the relationship between the predictor (burn) and outcome (liking), seen in Model 1 of Figure 1. If the interaction term accounts for a statistically significant amount of variance in the outcome variable, this is evidence of moderation. Here, our model tests whether the relationship between the perceived burn of a 25uM capsaicin stimulus and reported spicy food liking systematically varies across individuals as a function of personality.

Figure 1.

Visual representation of the moderation models tested here. Model 1 tests whether personality traits moderate the relationship between perceived intensity of burning/stinging of a 25uM capsaicin sample and liking of spicy foods. Model 2 tests whether personality moderates the relationship between liking and intake of spicy foods.

Based on our prior work showing strong to moderate correlations between Sensation Seeking (r = +0.50) and Sensitivity to Reward (r = +0.23) and spicy food liking (Byrnes & Hayes, 2013), we hypothesized that these personality traits would moderate the relationship between the perceived burning/stinging of 25uM capsaicin and the reported liking/disliking of spicy foods. A second aim of this study was to assess whether the relationship between liking and intake of spicy foods was moderated by personality. Finally, we also explored the role of gender, given the possible association of masculine traits with the consumption of spicy foods.

2. Methods

2.1. Overview

Similar to our previous report (Byrnes & Hayes, 2013), these data were collected as part of a larger, ongoing study of the genetics of oral sensation (Project GIANT-CS, phase I). Briefly, data were collected in one-on-one testing across multiple days, but only data from the first laboratory session and an online follow-up survey are reported here. During the first session, participants completed a food-liking questionnaire and rated the intensity of sensations from sampled stimuli, including capsaicin. After leaving the laboratory, participants filled out an online survey that included several different personality measures, as well as a measure of spicy food intake frequency.

2.2. Participants

Participants were recruited from the Penn State campus and the surrounding area. To be eligible, individuals needed to be non-smoking, fluent English speakers between 18 and 45 years old, with no known defect of taste or smell. Additional exclusion criteria included being pregnant or breastfeeding, taking prescription pain medications, the presence of lip, cheek, or tongue piercings, or prior diagnosis with a disorder involving either a loss of sensitivity or chronic pain. Participants who qualified were asked not to eat or drink within 1 hour of testing and were asked to abstain from eating hot and/or spicy foods for at least 48 hours prior to testing.

Present data are a superset of the cohort described previously (n=97; Byrnes & Hayes, 2013); here, we report data from 246 participants (99 men). Participant ages ranged from 18 to 45 (mean 25.9). Self reported race and ethnicity were collected as two separate questions, as recommended by the 1997 OMB Directive 15 guidelines. The present analysis included 35 Asians, 6 African Americans, and 172 Caucasians; 33 individuals did not report a race. For ethnicity, 12 individuals identified themselves as being Latina or Latino and 203 responded as being not Latina or Latino; 31 did not report an ethnicity.

2.3. Measuring Sensation Intensity

A general Labeled Magnitude Scale (Bartoshuk, Duffy et al., 2004) was used to collect all intensity ratings. Prior to rating any sampled stimuli, participants were oriented to the scale using a list of 15 imagined or remembered sensations that included both oral and non-oral items (Hayes, Allen et al., 2013). Both the scale instructions and orientation procedure encouraged participants to make ratings in a generalized context that was not limited to food or oral sensations. The top of the scale was labeled as the “strongest imaginable sensation of any kind”. For each sample, participants were asked to rate sweetness, bitterness, sourness, burning/stinging, umami/savory, and saltiness. All data were collected via Compusense five Plus, version 5.2 (Guelph, Ontario, Canada).

2.4. Sampled Stimuli

A 10 mL aliquot of 25 uM capsaicin was presented to participants as part of a series of six food grade stimuli; other food-grade stimuli included potassium chloride, quinine HCl, Acesulfame potassium, a MSG/IMP blend, and sucrose (Allen, McGeary et al., 2013). Presentation order was counterbalanced in a Williams Design to minimize carryover effects. This capsaicin concentration and volume were selected as they evoke burning sensations above ‘strong’ on a general Labeled Magnitude scale (gLMS) in sip and spit experiments (e.g. Hayes, Allen et al., 2013). Capsaicin was first dissolved in ethanol and then diluted to volume as described previously (Byrnes & Hayes, 2013). All stimuli (10 mL) were presented in plastic medicine cups at room temperature. Participants rinsed twice with room temperature reverse osmosis (RO) water prior to the first stimulus and then ad libitum between each subsequent stimulus; a minimum interstimulus interval of 30 seconds was enforced, and the experimenter did not provide the next sample until the participant reported all sensations from the previous stimulus were gone. After swirling a sample in his or her mouth for three seconds and expectorating, but prior to rinsing, participants were asked to rate six sensation qualities (see Allen, McGeary et al., 2013) for each stimulus; only burning/stinging ratings for capsaicin are used here.

2.5. Measuring Food Preference

During the first visit to the laboratory, participants completed a generalized Degree of Liking (gDOL) questionnaire; critically, this approach differs from most food preference questionnaires in that it includes non-food items to help generalize affective responses outside of a context solely focused on food. Other recent examples of generalized hedonic questionnaires have been described elsewhere (Duffy, Hayes et al., 2009; Peracchio, Henebery et al., 2012; Pickering, Jain et al., 2012; Scarmo, Henebery et al., 2012). The version of the gDOL used here is a 63-item survey with 27 foods, 20 alcoholic beverages, and 16 non-food items. Hedonic ratings were collected on a bipolar, horizontal visual analog scale, with the ends of the scale being labeled ‘strongest disliking of any kind’ (left side) and ‘strongest liking of any kind’ (right side); the midpoint of the scale was labeled ‘neutral’. Here, our analyses focused on affective ratings for three of the 27 food items on the gDOL: ‘burn of a spicy meal’, ‘spicy Asian food’, and ‘liking of spicy and/or BBQ ribs’.

2.6. Web-based questionnaire

After the first laboratory session, participants completed a web-based personality survey that included items from the Private Body Consciousness (Miller, Murphy et al., 1981), Arnett's Inventory of Sensation Seeking (AISS; Arnett 1994), and the Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ; Torrubia, Avila et al., 2001). For additional information on these measures, see Byrnes and Hayes (2013). For the remainder of this document, we use lower case letters when referring to the general concept of sensation seeking, and use the phrase Sensation Seeking (capitalized) or the initialism AISS when referring to scores on Arnett's Inventory of Sensation Seeking (Arnett, 1994).

To assess typical intake, we adapted the question used previously by Lawless and colleagues (1985). We asked participants “How often do you consume all types of chili peppers in foods including Mexican, Indian, Chinese, Thai, Korean, and other foods that contain chili pepper and cause tingling or burning?” Responses were recorded on an 8-point category: scale (never, <1/month, 1-3/month, 1-2/week, 3-4/week, 5-6/week, 1/day, 2+/day) was used. These values were re-coded as a yearly frequency (e.g. 1-3/month=24, 3-4/week=182, 1/day=365, etc.) and log transformed prior to analysis to reduce skew.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC). All assumptions of multiple regression were assessed and were met after log transformation of the variable measuring yearly chili intake. No multicollinearity was noted between variables, so no centering was performed. Student's t-tests were conducted in SAS 9.2 comparing men and women on the various personality measures, liking of spicy foods, and annual intake of chilis using proc ttest with a Satterthwaite approximation of standard error. Significance criteria was set at alpha = 0.05.

Moderation was tested using the method from Baron and Kenny (Baron & Kenny, 1986). To test for moderation, personality was used in the model as an additional predictor of the outcome variable (liking) along with burn (the main predictor). A multiplicative interaction term (predictor × moderator; here, burn × personality) was included in the regression model in addition to the predictors of burn and personality (3 predictors in total). A significant interaction term was taken as evidence of moderation.

3. Results

Our participants showed wide variation in self-reported chili intake frequency (interquartile range [IQR]: 24-182 times per year), with a mean consumption frequency of 130±12 (mean ± standard error) times per year. Ratings of the perceived burning and stinging of a 25uM capsaicin sample were variable (possible range 0 to 100, IQR: 17.0-48.0), as were the liking scores for ‘burn of a spicy meal’ collected on a generalized hedonic survey (possible range -100 to 100, IQR: 0-52). We also observed sufficient variation in scores on the various personality measures to allow for further analyses. Out of a total possible range of 20 to 80, AISS scores ranged from 35-77 (IQR: 49.5-61.0). Out of a possible range of 0 to 24, SP scores ranged from 0 to 23 (IQR: 6.0-13.0) and SR scores ranged from 1 to 23 (IQR: 8.0 - 14.0).

3.1. Relationship between perceived burn of 25uM capsaicin, liking of spicy foods, and yearly chili intake

Negative correlations were observed between the perceived burn (i.e., suprathreshold intensity) of the 25uM capsaicin stimulus and the liking of a spicy meal (r = -0.25, p < 0.0001), liking of spicy Asian food (r = -0.17, p = 0.008), and liking of spicy and/or BBQ ribs (r = -0.19, p = 0.003). Annual chili intake was positively correlated with the liking of spicy meals (r = 0.37, p < 0.0001), liking of spicy Asian food (r = 0.41, p < 0.0001), and liking of spicy and/or BBQ ribs (r = 0.22, p = 0.001). No relationship was observed between annual chili intake and perceived burn intensity (r = -0.05, p = 0.46).

In men, perceived burn correlated with the liking of all 3 spicy food items (meals: r = -0.28, p = 0.005, Asian: r = -0.25, p = 0.01, BBQ: r = -0.23, p = 0.03), but only liking of spicy meals was positively correlated with annual chili intake (meals: r = 0.28, p = 0.01). In women, perceived burn correlated with the liking of all 3 spicy food items (meals: r = -0.24, p = 0.003, Asian: r = -0.15, p =0.08, BBQ: r = -0.18, p = 0.03), and all three were positively correlated with annual chili intake (meals: r = 0.42, p < 0.0001, Asian: r = 0.49, p < 0.0001, BBQ: r = 0.27, p = 0.003). Consistent with the results for the entire cohort, no relationship was observed between annual chili intake and perceived burn intensity when men or women were considered separately.

3.2. Relationship between personality traits and liking of spicy foods

In the full cohort, Sensation Seeking showed weak to moderate positive correlations with the liking of spicy meals, spicy Asian food, and spicy and/or BBQ ribs (meals: r = 0.37, p < 0.0001, Asian: r = 0.29, p < 0.0001, BBQ: r =0.16, p = 0.02). Sensitivity to Reward showed weak positive correlations with the liking of spicy meals and spicy Asian foods (meals: r = 0.18, p = 0.01, Asian: r = 0.16, p = 0.02). In the full cohort, personality did not modify the relationship between perceived burn from 25uM capsaicin and liking of spicy meals, spicy Asian food, and spicy and/or BBQ ribs (e.g. no moderation). Consistent with the Pearson correlations reported above, we observed significant main effects of Sensation Seeking and Sensitivity to Reward on the liking of all spicy foods (AISS; meal: β = 0.27, p = 0.02, Asian: β = 0.31, p = 0.01, BBQ: β = 0.26, p = 0.03, SR; meal: β = 0.24, p = 0.06, Asian: β = 0.32, p = 0.01, BBQ: β = 0.29, p = 0.03) in these moderation models.

3.3. Relationships between perceived burn intensity, liking of spicy foods, and personality differ between men and women

In men, Sensation Seeking showed a moderate positive correlation with the liking of a spicy meal (r = 0.32, p = 0.004). The relationship between Sensitivity to Reward and the liking of a spicy meal also showed a positive trend (r = 0.21, p = 0.06). In women, Sensation Seeking showed a moderate positive relationship with the liking of a spicy meal (r = 0.34, p < 0.0001) and the liking of spicy Asian foods (r = 0.29, p = 0.001); conversely Sensitivity to Reward showed no relationships with liking for any of the spicy food items. Men also showed a negative relationship between Sensation Seeking and perceived burn intensity of the sample (r = -0.24, p = 0.03) as well as a positive trend between Sensitivity to Punishment and perceived burn intensity (r = 0.21, p = 0.054). No such relationships were observed in women.

Table 1 summarizes the models testing whether personality moderates the relationship between perceived burn and liking of spicy foods. In men, a main effect of Sensitivity to Reward on liking of all spicy foods was observed (Table 1; meal: β = 0.55 p = 0.02, Asian: β = 0.60, p = 0.01, BBQ: β = 0.56, p = 0.03) as well as a moderator effect of SR on the relationship between perceived intensity of burning and liking of spicy Asian foods (β = -0.96, p = 0.03). A main effect of Sensation Seeking on the liking of a spicy meal (β = 0.28, p = 0.05) and spicy Asian foods (β = 0.34, p = 0.02) was observed in women (top model in the bottom panel of Table 1). No moderation of the relationship between perceived burn and the liking of spicy foods was observed in women.

Table 1.

Moderator effects of personality on the relationship between perceived intensity of burning/stinging and liking of spicy foods. The 3 columns on the right of the table report data for separate models for the three spicy food items on the gDOL survey. In the first column, the various terms in the model are given, where BS is perceived burning/stinging intensity from 25uM capsaicin, AISS is Sensation Seeking, SP is Sensitivity to Punishment and SR is Sensitivity to Reward. Standardized regression coefficients are reported. Significant main effects of personality or burning/stinging intensity and significant interaction effects are highlighted.

| FULL COHORT (N=246) | Spicy Meal | Spicy Asian Foods | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs |

|---|---|---|---|

| BS | -0.47 | -0.02 | 0.245 |

| AISS | 0.27* | 0.31** | 0.26* |

| BS × AISS | 0.26 | -0.12 | -0.43 |

| Model (3,212) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.17*** | 0.09*** | 0.05** |

| BS | -0.12 | -0.04 | -0.31* |

| SP | -0.003 | 0.05 | -0.28 |

| BS × SP | -0.15 | -0.16 | 0.19 |

| Model (3,214) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.06** | 0.02 | 0.024* |

| BS | -0.18 | 0.04 | 0.041 |

| SR | 0.24 | 0.32* | 0.29* |

| BS × SR | -0.09 | -0.28 | -0.31 |

| Model (3,214) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.08*** | 0.05** | 0.046** |

|

| |||

| MEN (N=99) | Spicy Meal | Spicy Asian Foods | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs |

|

| |||

| BS | -0.84 | -0.52 | -1.30 |

| AISS | 0.11 | 0.01 | -0.21 |

| BS × AISS | 0.58 | 0.29 | 1.05 |

| Model (3,73) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.14** | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| BS | -0.14 | -0.15 | -0.10 |

| SP | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.18 |

| BS × SP | -0.25 | -0.19 | -0.22 |

| Model (3,78) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| BS | 0.16 | 0.49 | 0.31 |

| SR | 0.55* | 0.60* | 0.51* |

| BS × SR | -0.61 | -0.96* | -0.72 |

| Model (3,150) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.13** | 0.09* | 0.08* |

|

| |||

| WOMEN (N=147) | Spicy Meal | Spicy Asian Foods | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs |

|

| |||

| BS | -0.38 | 0.10 | 0.66 |

| AISS | 0.28* | 0.34* | 0.29 |

| BS × AISS | 0.18 | -0.23 | -0.87 |

| Model (3,150) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.14** | 0.08** | 0.03 |

| BS | -0.10 | 0.05 | -0.43* |

| SP | -0.02 | 0.09 | -0.19 |

| BS × SP | -0.16 | -0.24 | 0.37 |

| Model (3,150) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.12 | 0.002 | 0.02 |

| BS | -0.32 | -0.11 | -0.04 |

| SR | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.09 |

| BS × SR | 0.11 | -0.04 | -0.16 |

| Model (3,150) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.04* | 0.02 | 0.01 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

3.4. Relationship between personality and reported yearly chili intake

Sensation Seeking and Sensitivity to Reward showed significant positive correlations with reported chili intake in the full dataset (AISS: r = 0.16, p = 0.02, SR: r = 0.19, p = 0.005). In models assessing whether personality moderates of the relationship between the liking of spicy foods and yearly intake (i.e. Model 2 in Figure 1), moderation was observed only for some personality traits. These results are summarized in Table 2. When considering men and women together (all 246 participants), main effects were noted for liking of spicy meals and spicy Asian foods on reported intake in the moderation model with Sensitivity to Reward (top panel of Table 2; meal: β= 0.58, p = 0.002, Asian: β = 0.53, p = 0.003). In these models, there was also a main effect of Sensitivity to Reward on yearly intake (top panel of Table 2). Conversely, Sensitivity to Punishment did not associate with intake (top panel of Table 2). Strikingly, Sensation Seeking did not associate with intake in models that account for liking (top panel of Table 2). Generally, we did not find evidence that personality moderates the relationship between liking and intake, with one exception: Sensitivity to Punishment influenced of the relationship between the liking of a spicy meal and intake (β =0.30, p = 0.02).

Table 2.

Moderator effects of personality on the relationship between liking and intake of spicy foods. Main effects of spicy foods (spicy meal, spicy Asian foods, or spicy and or BBQ spare ribs), and personality (AISS, SP, or SR), are reported for each model as well as interaction effects of spicy food and personality. AISS is Sensation Seeking, SP is Sensitivity to Punishment, and SR is Sensitivity to Reward. Standardized regression coefficients are reported. Significant main effects of personality or liking of spicy foods and significant interaction effects are highlighted.

| FULL COHORT (N=246) | Intake | Intake | Intake | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spicy Meal | 0.52 | Spicy Asian Foods | 0.59 | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs | 0.45 |

| AISS | 0.11 | AISS | 0.15 | AISS | 0.29 |

| Spicy Meal × AISS | -0.1 | Spicy Asian Foods × AISS | -0.17 | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs × AISS | -0.25 |

| Model (3,198) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.22*** | Model (3,196) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.21*** | Model (3,188) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.12*** |

| Spicy Meal | 0.21 | Spicy Asian Foods | 0.34* | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs | 0.1 |

| SP | -0.07 | SP | -0.04 | SP | -0.1 |

| Spicy Meal × SP | 0.30* | Spicy Asian Foods × SP | 0.14 | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs × SP | 0.18 |

| Model (3,198) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.22*** | Model (3,196) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.20*** | Model (3,188) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.05** |

| Spicy Meal | 0.58** | Spicy Asian Foods | 0.53** | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs | 0.16 |

| SR | 0.24** | SR | 0.23* | SR | 0.21* |

| Spicy Meal × SR | -0.17 | Spicy Asian Foods × SR | -0.13 | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs × SR | 0.07 |

| Model (3,198) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.24*** | Model (3,196) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.24*** | Model (3,188) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.10*** |

|

| |||||

| MEN (N=99) | Intake | Intake | Intake | ||

|

| |||||

| Spicy Meal | 0.86 | Spicy Asian Foods | 0.43 | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs | -0.36 |

| AISS | 0.26 | AISS | 0.31 | AISS | 0.19 |

| Spicy Meal × AISS | -0.59 | Spicy Asian Foods × AISS | -0.26 | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs × AISS | 0.47 |

| Model (3,77) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.13** | Model (3,77) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.07* | Model (3,75) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.05 |

| Spicy Meal | 0.06 | Spicy Asian Foods | 0.26 | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs | -0.06 |

| SP | -0.29 | SP | -0.08 | SP | -0.24 |

| Spicy Meal × SP | 0.39 | Spicy Asian Foods × SP | -0.07 | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs × SP | 0.25 |

| Model (3,77) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.14** | Model (3,77) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.02 | Model (3,75) Adj. R-Sq. | -0.01 |

| Spicy Meal | 0.79* | Spicy Asian Foods | 0.63 | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs | 0.14 |

| SR | 0.38** | SR | 0.52* | SR | 0.32 |

| Spicy Meal × SR | -0.54 | Spicy Asian Foods × SR | -0.53 | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs × S | -0.06 |

| Model (3,77) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.18** | Model (3,77) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.11** | Model (3,75) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.07* |

|

| |||||

| WOMEN (N=147) | Intake | Intake | Intake | ||

|

| |||||

| Spicy Meal | 0.29 | Spicy Asian Foods | 0.49 | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs | 0.74 |

| AISS | 0.01 | AISS | -0.01 | AISS | 0.28** |

| Spicy Meal × AISS | 0.21 | Spicy Asian Foods × AISS | 0.08 | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs × AISS | -0.48 |

| Model (3,120) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.24*** | Model (3,118) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.31*** | Model (3,112) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.12** |

| Spicy Meal | 0.19 | Spicy Asian Foods | 0.3 | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs | 0.1 |

| SP | 0.05 | SP | 0.03 | SP | -0.03 |

| Spicy Meal × SP | 0.37* | Spicy Asian Foods × SP | 0.31 | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs × SP | 0.22 |

| Model (3,120) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.28*** | Model (3,118) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.34*** | Model (3,112) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.07* |

| Spicy Meal | 0.41 | Spicy Asian Foods | 0.47* | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs | 0.17 |

| SR | 0.14 | SR | 0.094 | SR | 0.13 |

| Spicy Meal × SR | 0.09 | Spicy Asian Foods × SR | Spicy/BBQ Spare Ribs × SR | 0.13 | |

| Model (3,120) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.26*** | Model (3,118) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.32*** | Model (3,112) Adj. R-Sq. | 0.09** |

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

3.5. Relationship between liking of spicy foods, reported yearly chili intake, and personality differ between men and women

In simple Pearson correlations that did not account for other factors, no relationship was observed between personality and yearly chili intake in men, while a positive correlation was observed between Sensitivity to Reward and reported yearly intake of chilis in women (r = 0.17, p = 0.04). However, the regression models summarized in the middle and bottom panels of Table 2 provide a more nuanced view. In men, Sensation Seeking or Sensitivity to Punishment did not directly predict reported annual chili intake; nor was there any evidence of moderation with AISS or SP. Conversely, direct effects of Sensitivity to Reward were observed in two of the models (middle panel of Table 2; spicy meal: β = 0.38, p = 0.01, spicy Asian foods: β = 0.52, p = 0.01), but there was no evidence SR moderated the liking intake relationship. In women, no consistent patterns emerged between personality constructs and intake of spicy foods: Sensation Seeking predicted yearly chili intake, but only in the model with spicy and/or BBQ ribs (β = 0.28, p = 0.006), and liking of Asian foods predicted yearly chili intake, but only in the model with Sensitivity to Reward (β = 0.47, p = 0.03) were observed. There was evidence that Sensitivity to Punishment moderated the relationship between the liking of a spicy meal and the yearly chili intake (β = 0.37, p = 0.03).

4. Discussion

Here, we used regression based models of moderation to explore the nature of the relationships between the perceived burn of a 25uM capsaicin stimulus, remembered liking of a spicy meals, reported yearly chili intake, and a number of personality traits. These traits included including Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward (O'Connor, Colder et al., 2004; Torrubia, Avila et al., 2001) and Sensation Seeking (as measured with Arnett's Inventory; Arnett, 1994). This work builds on our recent work showing strong to moderate correlations between the liking of spicy foods and some of these personality constructs (Byrnes & Hayes, 2013). Here, we extend this work in a superset of the previous cohort, showing that the nature of the relationships that are observed between perceived burning, liking, and intake differ between men and women.

In theory, the perceived intensity of burning/stinging sensation elicited by capsaicin presumably influences an individual's liking of capsaicin-containing foods, which thus influences his/her yearly intake of capsaicin-containing foods. However, with regular dosing via habitual intake of capsaicin-containing foods, use can also influence the perceived intensity of capsaicin through desensitization (Green & Hayes, 2003; Karrer & Bartoshuk, 1991; Lawless, Rozin et al., 1985; Stevenson & Prescott, 1994). Here, there was no evidence of desensitization in either men or women, indicating that variables other than changes in the perceived intensity of the burning/stinging sensation of capsaicin (i.e. tolerance) must be driving liking and consumption of spicy foods.

Consistent with prior findings (Byrnes & Hayes, 2013), we show here that perceived burning/stinging intensity of sampled capsaicin is inversely related to liking of spicy foods (spicy meals, spicy Asian foods, spicy and/or BBQ ribs). However, these relationships are weak, suggesting that additional factors likely influence an individual's liking of spicy foods. We also show that liking of spicy foods predicts annualized intake of capsaicin-containing foods and that the personality traits Sensation Seeking, Sensitivity to Reward, and Sensitivity to Punishment are related to the liking and intake of capsaicin-containing foods. To elucidate the nature of relationships that exist between the perceived burn from capsaicin, the liking of spicy foods, intake of these foods, and personality traits, moderator analysis was conducted using the framework proposed by Baron and Kenny (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Given the relationships observed in our previous study, we hypothesized that Sensation Seeking and Sensitivity to Reward would moderate the relationship between perceived burn intensity and liking of spicy foods. However, we saw no moderation by Sensation Seeking and limited moderation by Sensitivity to Reward. Sensitivity to Punishment also showed moderator effects. Most strikingly, we observed evidence that the relationships between personality traits and the liking and intake of spicy foods are different between men and women.

In the sample as a whole, intensity of perceived burn from sampled capsaicin predicted remembered liking of spicy foods, which in turn predicted yearly intake of capsaicin-containing foods. Additionally, the personality traits Sensation Seeking and Sensitivity to Reward showed significant associations with liking and intake of chili-containing foods. Based in these findings, along with our prior work (Byrnes & Hayes, 2013), it was expected that differences in AISS and SR might account for some of the differences seen in liking of spicy foods given the weak relationship between perceived burning/stinging intensity and liking of spicy foods. The original hypothesis was that for individuals high in Sensation Seeking and Sensitivity to Reward, the perceived burning/stinging intensity of capsaicin would influence their liking of capsaicin less than in low Sensation Seeking or Sensitivity to Reward individuals. In the full cohort, no moderator effects were observed for either trait on this relationship.

Interestingly, the relationships between perceived burning/stinging, yearly intake of chili-containing foods, the liking of spicy foods, and personality, were markedly different between men and women. Overall, men showed stronger negative correlations between perceived burning/stinging intensity and liking of spicy foods, suggesting that burning/stinging is more of a deterrent in men. In women, stronger positive relationships were noted between liking of spicy foods and yearly intake of chili-containing foods. Moderator analysis was conducted, using personality traits as the potential moderators, to explore if personality differences might be responsible for these discrepancies.

In moderator analysis conducted in the whole cohort, the only observed moderation was that of Sensitivity to Punishment on the relationship between liking and intake of spicy meals, which appears to be driven by women. AISS and SR showed significant main effects on all measures of liking and intake, however no moderation was observed by these constructs in the full cohort. In men, SR showed significant main effects on the liking of spicy foods when accounting for perceived burning/stinging and on the intake of spicy foods when accounting for liking of spicy foods. These results suggest that the relationship between SR and liking of spicy foods and the relationship between SR and intake of spicy foods may be distinct from one another.

In women, AISS showed stronger effects. When accounting for perceived burning/stinging, AISS showed significant main effects on liking of a spicy meal and spicy Asian food but not for spicy/BBQ ribs. In the moderation models assessing the relationship between AISS, liking of spicy foods, and intake of spicy foods, there was no main effect of AISS on intake noted in the models where liking of a spicy meal and liking of spicy Asian food, but a main effect of AISS on intake of spicy/BBQ ribs was noted even when accounting for liking of spicy/BBQ ribs. These data suggest that the effect of AISS on intake of a spicy meal and intake of spicy Asian food may act through liking in women, while the effect of AISS on intake of spicy/BBQ ribs may act through a path that is distinct from liking.

Overall, it seems likely that Sensitivity to Reward and Sensation Seeking may tap into different aspects of what makes spicy food enjoyable. While the personality constructs of Sensation Seeking and Sensitivity to Reward are correlated (Byrnes & Hayes, 2013; Torrubia, Avila et al., 2001; Zuckerman & Neeb, 1979), they are not interchangeable constructs (Scott-Parker, Watson et al., 2012; Torrubia, Avila et al., 2001). Indeed, our study is not the first to report differential effects between the two scales (Mobbs, Crepin et al., 2010; Scott-Parker, Watson et al., 2012).

Sensitivity to Reward, an operationalization of Gray's Behavioral Approach System (BAS), is composed of items that describe reactivity in situations that are predominantly rewarding. The items on this subscale of the SPSRQ deal with specific rewards, such as money, sex, social power, and approval (Caseras, Avila et al., 2003; O'Connor, Colder et al., 2004; Torrubia, Avila et al., 2001). AISS, on the other hand, is designed to assess the tendency of an individual to enjoy novel or intense sensations in addition to the tendency to seek out those sensations (Arnett, 1994; Zuckerman & Neeb, 1979). It has been proposed that individuals high in trait sensation seeking have chronically lower levels of cortical arousal than their low sensation seeking counterparts (Zuckerman, 2007). The key difference between high and low sensation seekers has to do with response to arousing stimuli. High sensation seekers enjoy these experiences because the stimulation brings them closer to their optimal level of cortical arousal, making the stimuli pleasant. Conversely, low sensation seekers operate at a baseline level that is closer to their optimal level of arousal, so these stimulating sensations push them beyond this optimal level, and are thus unpleasant. Thus, AISS may tap into rewards that are more biologically based, rather than socially based, as with SR.

In the 1980s, Rozin observed that in Mexican culture, chili consumption was socially associated with strength, and possibly the Mexican idea of machismo (Rozin & Schiller, 1980). Notably, there were no significant sex differences regarding preference of chili peppers in the Mexican sample, limiting the idea that there might be a social or sexual significance in that culture. In the present sample, men rated the liking of all spicy foods significantly higher than women (all p's < 0.05). It is possible that the cultural association of consuming spicy foods with strength and machismo has created a learned social reward for men. Conversely, for women these social forces are not present, and thus intrinsic factors remain as the primary motivation for consuming spicy foods. These conclusions are tentative; as additional work is needed to better understand the sensations that consuming spicy foods elicit and the biological bases that underlie the associated sensory and affective responses.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we build upon earlier findings from our lab, showing empirical evidence for the association between the personality traits Sensation Seeking and Sensitivity to Reward and the liking and intake of spicy foods. Once again, significant associations between these personality traits and the liking and intake of spicy foods were observed. Given the possible association of liking and consumption of spicy foods with masculine traits and machismo (Rozin & Schiller, 1980), we examined differences in the relationships of personality traits with liking and intake of spicy foods between men and women. In men, Sensitivity to Reward tended to show stronger effects than the other personality measures, while in women, Sensation Seeking showed stronger effects than the other personality measures. These results suggest that in men the consumption of spicy foods may be more strongly motivated by extrinsic rewards, while women appear to be motivated more strongly by intrinsic rewards. It is possible that these findings reflect different social learning or reward of consuming spicy foods between men and women This hypothesis is tentative, as further work is necessary to explore any possible biological differences in neurological response to capsaicin that may play a role in determining liking or disliking of capsaicin-containing foods. Additionally, work examining perception of extrinsic rewards for consuming spicy foods may provide insight into differences between men and women. Collectively, present work suggests that personality variables influence the intake of spicy foods differently in men and women, and that the relationship between the variables of personality, perceived burning/stinging of capsaicin, liking of spicy foods, and consumption of spicy foods may differ between men and women.

Recently, we showed personality measures correlated with chili liking and intake

Here, we test if personality modifies relationships between burn intensity and spicy food liking

Limited moderation by personality seen

Sensation Seeking showed stronger effects in women

Sensitivity to Reward showed stronger effects in men

Relationship between variables influencing liking and intake of spicy foods may differ between men and women

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was completed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Doctorate of Philosophy at the Pennsylvania State University by the first author. The authors warmly thank Alissa A. Nolden, Meghan Kane, and Dr. Emma L. Feeney for their assistance with data collection, and our study participants for their time and participation.

Funding: This work was supported by a National Institute of Health grant [DC010904] from the National Institute National of Deafness and Communication Disorders to the corresponding author, and United States Department of Agriculture Hatch Project PEN04332 funds.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen AL, McGeary JE, Knopik VS, Hayes JE. Bitterness of the non-nutritive sweetener acesulfame potassium varies with polymorphisms in TAS2R9 and TAS2R31. Chemical senses. 2013;38(5):379–389. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjt017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. Sensation seeking : a new conceptualization and a new scale. Personality and Individual Differences. 1994;16:7. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoshuk L, Duffy VB, Green BG, Hoffman HJ, Ko CW, Lucchina LA, et al. Weiffenbach JM. Valid across-group comparisons with labeled scales: the GLMS versus magnitude matching. Physiology & Behavior. 2004;82(1):5. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoshuk LM. The biological basis of food perception and acceptance. Food Quality and Preference. 1993;4(1-2):12. [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes NK, Hayes JE. Personality factors predict spicy food liking and intake. Food Quality and Preference. 2013;28(1):8. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caseras X, Avila C, Torrubia R. The measurement of individual differences in Behavioural Inhibition and Behavioural Activation Systems: a comparison of personality scales. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;34:14. [Google Scholar]

- Cowart BJ. Development of taste perception in humans: sensitivity and preference throughout the life span. Psychol Bull. 1981;90(1):43–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy VB, Bartoshuk LM. Food acceptance and genetic variation in taste. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100(6):647–655. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy VB, Hayes JE, Sullivan BS, Faghri P. Surveying food and beverage liking: a tool for epidemiological studies to connect chemosensation with health outcomes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1170:558–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy VB, Lanier SA, Hutchins HL, Pescatello LS, Johnson MK, Bartoshuk LM. Food preference questionnaire as a screening tool for assessing dietary risk of cardiovascular disease within health risk appraisals. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(2):237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eertmans A, Baeyens F, Van den Bergh O. Food likes and their relative importance in human eating behavior: review and preliminary suggestions for health promotion. Health Education Research. 2001;16(4):443–456. doi: 10.1093/her/16.4.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan V, Sathyanarayana M. Capsicum—production, technology, chemistry, and quality. Part V. Impact on physiology, pharmacology, nutrition, and metabolism; structure, pungency, pain, and desensitization sequences. Critical Reviews in Food Science & Nutrition. 1991;29(6):435–474. doi: 10.1080/10408399109527536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BG, Hayes JE. Capsaicin as a probe of the relationship between bitter taste and chemesthesis. Physiol Behav. 2003;79(4-5):811–821. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00213-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JE, Allen AL, Bennett SM. Direct comparison of the generalized visual analog scale (gVAS) and general labeled magnitude scale (gLMS) Food Quality and Preference. 2013;28(1):8. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes CA, Miles JNV, Clements K. A confirmatory factor analysis of two models of sensation seeking. Personality and Individual Differences. 2000;29:7. [Google Scholar]

- IFIC. Food & Health Survey: Consumer Attitudes toward Food Safety, Nutrition, and Health. Washington, DC: International Food Information Council Foundation; 2014. p. 90. [Google Scholar]

- Karrer T, Bartoshuk L. Capsaicin desensitization and recovery on the human tongue. Physiology & behavior. 1991;49(4):757–764. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(91)90315-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawless H, Rozin P, Shenker J. Effects of oral capsaicin on gustatory, olfactory and irritant sensations and flavor identification in humans who regularly or rarely consume chili pepper. Chemical Senses. 1985;10(4):579–589. [Google Scholar]

- Logue AW, Smith ME. Predictors of food preferences in adult humans. Appetite. 1986;7(2):109–125. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(86)80012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucier G, Pollack S, Ali M, Perez A. Fruit and vegetable backgrounder. US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ludy MJ, Mattes RD. The effects of hedonically acceptable red pepper doses on thermogenesis and appetite. Physiol Behav. 2011a;102(3-4):251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludy MJ, Mattes RD. Noxious stimuli sensitivity in regular spicy food users and non-users: Comparison of visual analog and general labeled magnitude scaling. Chemosensory Perception. 2011b;4(4):10. [Google Scholar]

- Ludy MJ, Mattes RD. Comparison of sensory, physiological, personality, and cultural attributes in regular spicy food users and non-users. Appetite. 2012;58(1):19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludy MJ, Moore GE, Mattes RD. The effects of capsaicin and capsiate on energy balance: critical review and meta-analyses of studies in humans. Chemical Senses. 2012;37(2):103–121. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjr100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto T, Miyawaki C, Ue H, Yuasa T, Miyatsuji A, Moritani T. Effects of capsaicin-containing yellow curry sauce on sympathetic nervous system activity and diet-induced thermogenesis in lean and obese young women. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2000;46(6):309–315. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.46.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller IJ, Jr, Reedy FE., Jr Variations in human taste bud density and taste intensity perception. Physiol Behav. 1990;47(6):1213–1219. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90374-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LC, Murphy R, Buss AH. Consciousness of body: private and public. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1981;41(2):9. [Google Scholar]

- Mobbs O, Crepin C, Thiery C, Golay A, Van der Linden M. Obesity and the four facets of impulsivity. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79(3):372–377. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor RM, Colder CR, Hawk J LW. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;37:17. [Google Scholar]

- Peracchio HL, Henebery KE, Sharafi M, Hayes JE, Duffy VB. Otitis media exposure associates with dietary preference and adiposity: a community-based observational study of at-risk preschoolers. Physiol Behav. 2012;106(2):264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering GJ, Jain AK, Bezawada R. Super-tasting gastronomes? Taste phenotype characterization of< i> foodies</i> and< i> wine experts</i>. Food Quality and Preference 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Randall E, Sanjur D. Food preferences-their conceptualization and relationship to consumption. Ecology of Food and Nutrition. 1981;11(3):10. [Google Scholar]

- Reinagel M. Today's Contemporary Spice Cabinet, 2014. 2012 from http://www.foodandnutrition.org/Winter-2012/Todays-Contemporary-Spice-Cabinet/

- Rozin P. Getting to like the burn of chili pepper: biological, psychological, and cultural perspectives. In: Green BG, Mason FR, Kare MR, editors. Chemical Senses, Vol 2: Irritation. New York: Dekker; 1990. pp. 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Rozin P, Rozin E. Culinary themes and variations. Natural History. 1981;90:8. [Google Scholar]

- Rozin P, Schiller D. The nature and acquisition of a preference for chili pepper by humans. Motivation and Emotion. 1980;4(1):24. [Google Scholar]

- Rozin P, Zellner D. The role of Pavlovian conditioning in the acquisition of food likes and dislikes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1985;443:189–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1985.tb27073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarmo S, Henebery K, Peracchio H, Cartmel B, Lin H, Ermakov IV, et al. Mayne ST. Skin carotenoid status measured by resonance Raman spectroscopy as a biomarker of fruit and vegetable intake in preschool children. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66(5):555–560. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutz HG. Performance ratings as predictors of food consumption. American Psychologist. 1957;12 [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Parker B, Watson B, King MJ, Hyde MK. The influence of sensitivity to reward and punishment, propensity for sensation seeking, depression, and anxiety on the risky behaviour of novice drivers: a path model. Br J Psychol. 2012;103(2):248–267. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.2011.02069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens DA. Individual differences in taste perception. Food Chemistry. 1996;56(3):8. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson RJ, Prescott J. The effects of prior experience with capsaicin on ratings of its burn. Chemical Senses. 1994;19(6):651–656. doi: 10.1093/chemse/19.6.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson RJ, Yeomans MR. Differences in ratings of intensity and pleasantness for the capsaicin burn between chilli likers and non-likers; implications for liking development. Chemical Senses. 1993;18:11. [Google Scholar]

- Terasaki M, Imada S. Sensation Seeking and Food Preferences. Personality and Individual Differences. 1988;9(1):87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Torrubia R, Avila C, Molto J, Caseras X. The Senstivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ) as a measure of Gray's anxiety and impulsivity dimensions. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;31(6):5. [Google Scholar]

- Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Smeets A, Lejeune MP. Sensory and gastrointestinal satiety effects of capsaicin on food intake. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29(6):682–688. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka M, Imanaga M, Ueyama H, Yamane M, Kubo Y, Boivin A, et al. Kiyonaga A. Maximum tolerable dose of red pepper decreases fat intake independently of spicy sensation in the mouth. Br J Nutr. 2004;91(6):991–995. doi: 10.1079/BJN20041148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka M, Lim K, Kikuzato S, Kiyonaga A, Tanaka H, Shindo M, Suzuki M. Effects of red-pepper diet on the energy metabolism in men. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 1995;41(6):647–656. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.41.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka M, St-Pierre S, Drapeau V, Dionne I, Doucet E, Suzuki M, Tremblay A. Effects of red pepper on appetite and energy intake. Br J Nutr. 1999;82(2):115–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Sensation Seeking and Risk. American Psychological Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M, Neeb M. Sensation seeking and psychopathology. Psychiatry Res. 1979;1(3):255–264. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(79)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]