Abstract

Drawing from 2 largely isolated approaches to the study of social stress—stress proliferation and minority stress—the authors theorize about stress and mental health among same-sex couples. With this integrated stress framework, they hypothesized that couple-level minority stressors may be experienced by individual partners and jointly by couples as a result of the stigmatized status of their same-sex relationship—a novel concept. They also consider dyadic minority stress processes, which result from the relational experience of individual-level minority stressors between partners. Because this framework includes stressors emanating from both status- (e.g., sexual minority) and role-based (e.g., partner) stress domains, it facilitates the study of stress proliferation linking minority stress (e.g., discrimination), more commonly experienced relational stress (e.g., conflict), and mental health. This framework can be applied to the study of stress and health among other marginalized couples, such as interracial/ethnic, interfaith, and age-discrepant couples.

Keywords: dyadic/couple data, gay, lesbian, bisexual mental health, stress coping and/or resiliency, theory construction

Evolving theories of how people experience stressful events and chronic stressors and strains over the course of their lives have contributed greatly to current understandings of the social determinants of well-being. Two related but distinct frameworks for examining the origins and effects of social stress on mental health are (a) stress proliferation and (b) minority stress theory. Both originate from broader conceptualizations of social stress theory (Dohrenwend, 2000; Pearlin, 1999), which posits that social stressors—events or circumstances that require individuals to adapt to changes intrapersonally, interpersonally, or in their environment—can be harmful to mental health. However, each framework facilitates the examination of distinct research questions. Stress-proliferation approaches foster the study of how stress can expand and proliferate within constellations of interrelated stressors in individual lives and within key relationships. Minority stress theory highlights the unique stress experiences of persons who belong to socially disadvantaged populations, or are viewed as such by others.

We argue that integrating these two conceptualizations of stress furthers scholars’ existing understanding of stress experience and how it influences mental health, as well as how it leads to persistent mental health disparities between minority and nonminority populations. To illustrate this potential, in this article we provide an integrated theoretical model of minority stress and mental health among same-sex couples. This extension of social stress theory informs future studies not only of social stress and mental health among sexual minority populations but also of the relational context of stress experience among other minority populations (e.g., racial/ethnic minorities), and it has the potential to advance understandings of dyadic stress processes among heterosexual couples and other types of relationships (e.g., interracial/ethnic couples, parent–child, siblings).

Stress Process and Forms of Stress Proliferation

Social stress process theory (Pearlin, Menaghan, Lieberman, & Mullan, 1981) fundamentally addresses the reality that stress, of different types (e.g., eventful and chronic) and from varying sources, can become involved in a causal dynamic over time to influence individual well-being. The terms stressors, stress, and distress are used to describe the stress process, with exposure to stressors leading to the experience of stress, which in turn may lead to distress. Stressors are seen as external challenges to individuals’ adaptive capacities and distress is defined as maladaptive responses to stress, such as depression, anxiety, fear, anger, or aggression. Stress is often defined as a biological response of the body to stressors, but in some literatures the terms stressor and stress are synonymous. In the psychosocial approach, it has proven more useful to define stressors than stress because it remains unclear whether stressors precipitate distress only through bodily stress response (Wheaton, Young, Montazer, & Stuart-Lahman, 2013). It is with this basic understanding of the stress process that we approach the study of stress experience in the context of intimate relationships.

The general conceptualization of stress as a process was developed to highlight the circumstances of social stress experience that influence individual health over time. One notable feature of the larger stress process is stress proliferation, which is based on the fact that life’s challenges and ongoing difficulties usually do not exist independently of one another. In short, stress proliferation refers to the observation that stress experiences often beget more stress in people’s lives, creating—in the absence of adequate psychosocial resources (e.g., a sense of mastery, effective coping strategies, social supports)—a causal chain of stressors that can directly and indirectly be harmful to mental health (Aneshensel, Pearlin, Mullan, Zarit, & Whitlatch, 1995; Pearlin, 1999; Pearlin et al., 1981; Pearlin & Bierman, 2013).

This proliferation of stress as it is subjectively and objectively experienced by individuals—and between individuals within close relationships—has been empirically demonstrated (Brody et al., 2008; Pearlin, Aneshensel, & LeBlanc, 1997; Pearlin, Schieman, Fazio, & Meersman, 2005; Wight, Aneshensel, & LeBlanc, 2003). Although the reality that stress often leads to more stress applies to many life circumstances (e.g., racial/ethnic discrimination [Gee, Walsemann, & Brondolo, 2012], neighborhood disadvantage [Aneshensel, 2010]), it has been most fruitfully theorized within the context of significant social roles that individuals occupy (e.g., employee, parent, child, and spouse/partner) and the associated role sets through which these important social relationships (e.g., husband–wife, parent–child, employee–supervisor) are structured (Merton, 1938). Thus, researchers interested in empirically examining stress proliferation have tended to develop studies that focus on people’s experiences within key social roles, the obligations of such roles, and the social and interpersonal interactions attached to them (Milkie, 2010). This framing has provided fertile ground for understanding stress experience and health. Highlighting these role-based experiences also helps demonstrate how individuals linked together by key social roles can indeed share the experience of social stress.

Studies of informal caregivers and caregiving dyads facing the challenges of chronic illnesses or disabilities have proven to be an especially useful focal point for illuminating stress proliferation (Pearlin, Mullan, Semple, & Skaff, 1990). A series of such caregiving studies has produced compelling evidence to illustrate how care-related stressors may create a chain reaction of consequent stressors that diminish well-being, with most analyses focusing on the effects of stress on mental health (Aneshensel et al., 1995; LeBlanc, Aneshensel, & Wight, 1995; LeBlanc, London, & Aneshensel, 1997; Wight, 2000; Wight et al., 2003).

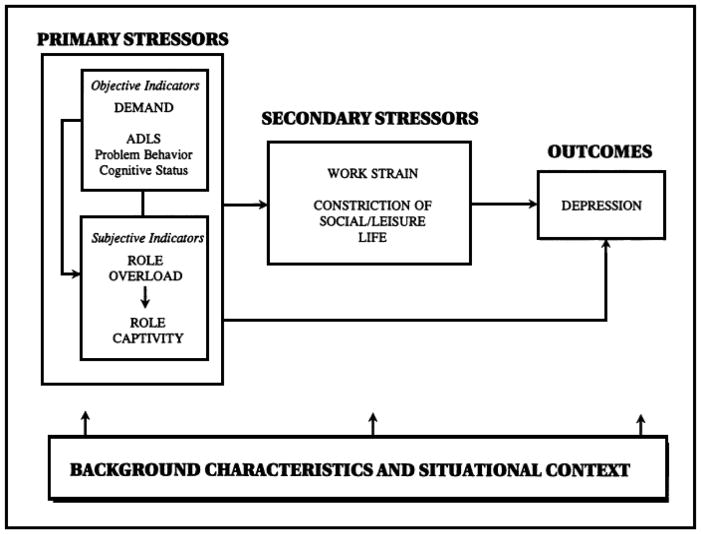

One study based on longitudinal data collected from a panel of AIDS caregivers in the early- to mid-1990s—prior to the introduction of effective treatments for HIV—articulated two critical stress processes that led to deleterious mental health effects among caregivers (Pearlin et al., 1997). The first focused on stressors rooted directly in the demands of the caregiving role, which are viewed as the primary sources of social stress. Through a process of primary stress expansion the objective demands of care (e.g., the ongoing tasks of assisting a person with activities of daily living such as eating, bathing, and dressing) were found, for some, to lead to heightened subjective appraisals of stress (e.g., feelings of entrapment in the caregiver role), which in turn had significant harmful effects on mental health. This is one form of stress proliferation. This study additionally depicted the movement of social stress from one life domain to another (e.g., work strain, constriction of leisure activities), to ultimately influence mental health, another form of stress proliferation.

Thus, in their examination of AIDS caregiving Pearlin et al. (1997) demonstrated how the primary stressors of care not only expanded to influence subjective appraisals of stress but also proliferated to create stress in other areas of the caregivers’ lives, which in turn had significant deleterious effects on mental health. Indeed, the mental health effects of such secondary stressors proved to be among the most pernicious. These two stress processes, each reflecting a distinct form of stress proliferation, are illustrated in Figure 1, reproduced from Pearlin et al. (1997), where arrows represent significant relationships between variables. This figure demonstrates a constellation of primary stressors (i.e., objective and subjectively experienced care-related stressors) and secondary stressors (e.g., work strain, constriction of social/leisure life) that are significantly interlinked, as well as significantly associated, directly and/or indirectly, with depression.

Figure 1.

Concepts and Measures for the Analysis of Stress Proliferation.

Note: From “The Forms and Mechanisms of Stress Proliferation: The Case of AIDS Caregivers,” by L. I. Pearlin, C. S. Aneshensel, and A. J. LeBlanc, 1997, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38, p. 227. Copyright 1997 by the American Sociological Association. Reprinted with permission. ADLS = XXXX.

Subsequent caregiving studies have examined both members of the caregiving dyad (caregiver and care recipient) to investigate crossover stress processes, or stress contagion, an additional form of stress proliferation that may affect the mental health of one or both individuals (Almeida, Wethington, & Chandler 1999; Bolger, DeLongis, Kessler, & Wethington, 1989a; Braun et al., 2009; Lyons, Zarit, Sayer, & Whitlatch, 2002; Wight, Aneshensel, LeBlanc, & Beals, 2008; Wight, Beals, Miller-Martinez, Murphy, & Aneshensel, 2007). This research illustrates the sharing of stress, whereby the difficulties or stressors faced by one person can intrude on the lives of those with whom they are close. For example, Wight et al.’s (2008) research empirically demonstrated how the dyadic experience of HIV-related future uncertainty affected the mental health of the care recipient but not the caregiver.

Finally, like all applications of stress process theory, stress proliferation frameworks examine constellations of stress as being situated within the larger structures of society, which fundamentally shape individual lives and relationships. This, too, is illustrated in Figure 1, where the pervasive influence of background characteristics (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status) and situational context (e.g., neighborhood of residence) on all aspects of stress proliferation is acknowledged. In this way, researchers interested in the study of stress processes are able to empirically adjust for and study the ways in which individual and interpersonal stressors can have their beginnings in social problems (Pearlin & Bierman, 2013).

Minority Stress Theory

Rather than viewing social roles like that of caregiver as critical sources of social stress experience, minority stress theory (Brooks, 1981; DiPlacido, 1998; Meyer, 2003a, 2003b; Meyer & Frost, 2013) focuses on types of social stress that are uniquely borne out of prevailing social systems that perpetuate structural, systematic, and interpersonal disadvantage for persons who identify as members of a minority group (e.g., sexual minorities, racial/ethnic minorities), or have disadvantaged social status (e.g., women). In this way, minority stress focuses on minority status as a useful window into stress experience.

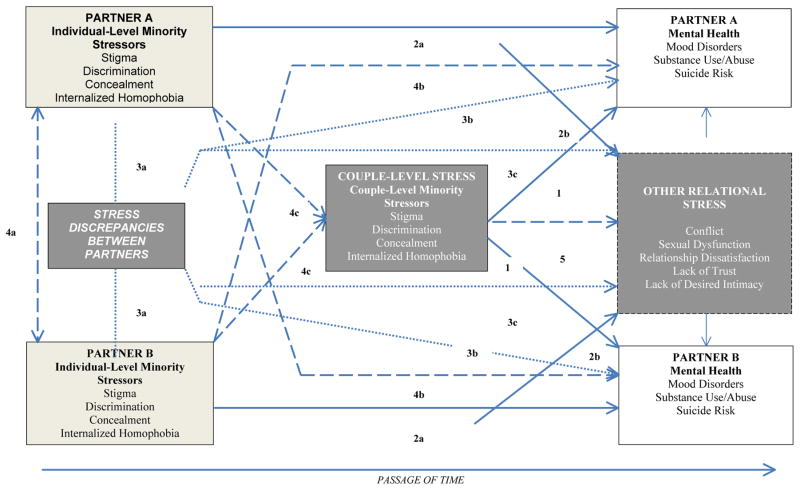

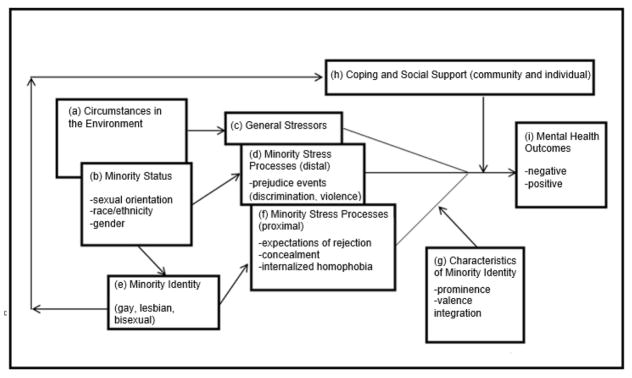

Minority populations are exposed to unique stressors, including stigma or expectations of rejection, experiences of discrimination (both acute events and chronic everyday mistreatment), internalization of negative social beliefs about one’s social groups or social identity, and stressors related to the concealment or management of a stigmatized identity (Frost, 2011b; Meyer, 2003b). As shown in Figure 2, reproduced from Meyer (2003b), such minority stressors exist on a continuum of proximity to the self. Stressors most distal to the self are objective stressors based primarily in the environment, such as prevailing stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. These lead to more proximal appraisals of the environment as threatening and result in expectations of rejection. Most proximal to the self are one’s internalizations of negative social attitudes toward one’s own minority group membership (e.g., internalized homophobia). It is theorized that such minority stressors—associated with minority statuses and identities—create strain on individuals’ abilities to adapt to, and function in, their everyday environments and are therefore associated with detriments to mental health. The existing research supports minority stress theory, consistently demonstrating significant relationships between minority stress experience and mental health (Meyer, 2003a, 2003b).

Figure 2.

Minority Stress Processes in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations.

Note: From “Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence,” by I. H. Meyer, 2003, Psychological Bulletin, 129, p. 679. Copyright 2003 by the American Psychological Association. Reprinted with permission.

Sexual minority populations have been a useful focal point in the application of minority stress theory. In a meta-analytic review of the epidemiology of mental disorders among heterosexual and sexual minority persons, Meyer (2003b) demonstrated important population differences in mental health between the two groups and attributed these differences to minority stressors. Epidemiological research has confirmed that sexual minority individuals experience significantly more social stress than heterosexuals (Meyer, Schwartz, & Frost, 2008) and that their experiences of minority stress contribute to their higher rates of mental disorder (Hatzenbuehler, Keyes, & Hasin, 2009; Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, Keyes, & Hasin, 2010; Mays & Cochran, 2001). Moreover, within-group studies have consistently demonstrated negative effects of minority stress on the mental health of sexual minority persons (e.g., Frost & Meyer, 2009; Frost, Parsons, & Nanín, 2007; Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Erickson, 2008; Igartua, Gill, & Montoro, 2003; Meyer, 1995; Shidlo, 1994; Szymanski, Chung, & Balsam, 2001; Wight, 2000; Wight, LeBlanc, de Vries, & Detels, 2012).

Contrasting Stress Proliferation and Minority Stress Approaches

There are limitations in the degree to which existing applications of stress proliferation and minority stress frameworks have been able to address the complexity of stress experience in peoples’ day-to-day lives. To begin, applications of stress proliferation frameworks have been most readily made in instances where exposure to primary stress can be observed and assessed in the context of a social role, such as that of informal caregiver, as well as where measurable secondary stressors in other life domains can be viewed as resulting from the role-based primary stressors. Although such designations about the causal ordering of stress have proven to be useful in the context of a social role that one acquires over time, it is not always possible to situate the origins of stress within the context of role incumbency and its enactment over time. Thus, researchers must consider ways to examine the movement of stress within a constellation of stressors associated with critical social roles as well as stressors emanating from other sources.

In contrast, minority stress theory largely ignores role-based stress, focusing instead on the social stress emanating from disadvantaged social statuses, identities, or group membership, and it does not examine stress experience related to other life domains. As a consequence, the relationship between general stress processes (experienced by the general population) and minority stressors (unique to disadvantaged minority populations) is not well understood. Minority stress researchers have examined moderators and mediators of minority stress (Balsam & Szymanski, 2005; Frost & Meyer, 2009; Lehavot & Simoni, 2011; Wight et al., 2012; Zamboni & Crawford, 2007); however, almost no research has examined minority stress within a stress proliferation framework. One exception is a caregiving study that simultaneously analyzed minority stressors and care-related stressors (primary and secondary), uncovering significant relationships between concealment of sexual minority status, secondary stress, and mental health among AIDS caregivers over time (Wight, 2002). The sparseness of such investigations highlights a clear void in the existing stress scholarship. Research that incorporates a larger constellation of stressors and stress processes will lead to the identification of previously unexamined minority stressors and minority stress processes that influence the mental health of sexual minority populations.

Although to date we have learned much about the powerful role of minority stressors in influencing the mental health of minority populations—and in explaining mental health disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual populations in particular—we lack nuanced understandings of how minority stressors may produce or exacerbate other types of stress over time through processes similar or analogous to those identified in existing applications of the stress proliferation framework.

Moreover, the lion’s share of research examining the associations between social stress and mental health—whether it has emerged as a study of stress process or of minority stress—has been analytically, if not theoretically, focused on the individual as the unit of analysis: the sole object, and victim, of stress. This is true in part because mental health is essentially constructed and measured as something people experience as individuals, and for this reason such a focus on individuals in stress research will remain important. Although sociological approaches to the study of stress clearly recognize its origins in social life and interpersonal relationships, social stress research, in terms of its application, largely ignores its relational context. For example, in the classic stress-proliferation studies of informal caregivers, the focus on the circumstances and experiences of one individual has been privileged over those of others with whom they are close (e.g., caregivers in relation to the recipients of their care provision). In addition, some studies have examined stress contagion in the forms of stress spillover (through intrapersonal processes) and stress crossover (through interpersonal processes) in the context of intimate relationships (e.g., Bolger et al., 1989a; Grzywacz, Almeida, & McDonald, 2002; Young, Schieman, & Milkie, 2014).

However, more work is needed to foster deeper understandings of individual mental health as it is influenced not only by individual-level stressors but also by stressors inherently and uniquely tied to their experiences as partners in close relationships. To illustrate, in a large body of literature concerning dyadic coping with stress among couples, dyadic stress is described along three dimensions: (a) the way each partner is affected by a stressor (i.e., directly or indirectly), (b) the origin of the stressor (i.e., from inside or outside of the couple), and (c) the time sequence in which each partner becomes involved in a coping process to respond to the stressor (see, e.g., Bodenmann, 2005). As noted above, existing research focusing on stress experience within dyads has tended to examine stress most readily in terms of the first dimension, as evidenced in studies of stress contagion between individuals.

The distinction inherent in the second dimension of dyadic stress—between stressors that are internal or external to the dyad—can be usefully employed to move the field forward toward the development of new couple-level stress constructs. Dyadic stressors, whether they are internal to the dyad (e.g., individuals’ perceptions of difficulties relating to sharing household tasks) or external to the dyad (individuals’ perceptions of challenges associated with troublesome colleagues or neighbors), have moved the focal point of theorizing, conceptualization, and measurement closer toward the couple level (Bodenmann, Ledermann, & Bradbury, 2007; Ledermann, Bodenmann, Rudaz, & Bradbury, 2010). However, they do not fully capture couple-level stressors that are jointly experienced (i.e., something that happens to the couple, as compared to something that happens to each partner as an individual). Moreover, they do not capture stress that arises directly—whether it is perceived or experienced either by individual partners or jointly by couples—because of the stigmatization or marginalization of their relationship in and of itself. The latter led us to focus on couple-level minority stress.

Our efforts to refine couple-level conceptualizations of dyadic stress are similar in some respects to the more well-developed conceptualizations and measurement of dyadic coping, which has proven to be of enormous value in understanding how individual partners can effectively cope together to reduce or manage stressors of different types as well as enhance the quality of their relationship (Bodenmann, 2005; Bodenmann & Cina, 2005; Bodenmann, Pihet, & Kayser, 2006). For example, recent distinctions made between comparative and systemic approaches to the conceptualization of dyadic coping are relevant because the former concerns the comparison of partners’ individual coping, whereas the latter concerns coping as an interactive, reciprocal process (Bodenmann, Meuwly, & Kayser, 2011).

Therefore, our goal is to develop a conceptualization of couple-level minority stress by adding a focus on the couple-level experience of minority stressors—alongside of the more typically studied dyadic stress processes—to future studies of stress proliferation in relational contexts. We do so in the following sections by demonstrating the value of more explicitly recognizing how some aspects of stress experience within intimate relationships, whether they involve stressors that are eventful or chronic, can be understood as emanating from social stigma associated with the relationship itself (i.e., couple-level minority stressors). In doing so, our focus on couple-level minority stressors is unique, highlighting the value of examining this unique domain of stress faced by sexual minority populations. This allows us to simultaneously examine stressors uniquely experienced by a minority population alongside the more commonly understood stressors faced by couples of all kinds.

Stress and Well-Being Among Same-Sex Couples: An Integrated Framework

A stress framework that integrates stress proliferation and minority stress concepts offers an opportunity to advance current thinking about existing social stress frameworks in several important ways. This framework (depicted in Figure 3) facilitates the conceptualization and assessment of minority stress experience at the couple level, suggesting a previously unexamined domain of stress as experienced in the relational context. In addition, it is developed to further the study of stress processes that link individual- and couple-level experiences of stress, as well as stressors emanating from both status- (e.g., sexual minority) and role-based (e.g., partner) stress domains as they affect mental health over time.

Figure 3.

Couple-Level Minority Stress: Framework and Mechanisms of Stress Proliferation

Note: The relationship between stress and mental health is reciprocal. Nonetheless, in this figure we focus on the stress-to-mental health relationship as a means of facilitating deeper understandings of the role of stress as a critical causal factor in determining mental health.

Couple-Level Minority Stressors

As noted above, applications of minority stress theory have been limited in focus to individual-level experiences of stressful events or circumstances. However, when sexual minority individuals enter into a romantic relationship with another person of the same sex, they then become vulnerable to unique couple-level minority stressors that they may experience individually or jointly with their same-sex partners because their relationship, in and of itself, is socially stigmatized or marginalized in some way. As we discuss below, couple-level minority stressors are qualitatively different from individual-level minority stressors, as well as from dyadic minority stress processes.

For example, a woman may hide the fact that she is a lesbian (individual-level stressor: concealment) from her father, whom she perceives to be homophobic, to avoid a range of unsupportive reactions he might have (e.g., individual-level stressor: expectation of rejection). Moreover, if—as a symbol of their commitment to one another—this same woman were to move in with the woman she has been dating for the past year, her status as a member of a same-sex couple may result in an experience of additional social stressors, above and beyond what she may experience as an individual. For instance, in addition to her personal identity concealment, she and her partner would now have to individually and jointly manage the visibility of their relationship (couple-level minority stressor: concealment), the lack of acceptance from at least one parent and potentially others in their respective families (couple-level minority stressor: expectation of rejection of the relationship or of the partner), and barriers to obtaining legal recognition of their relationship (e.g., couple-level minority stressor: discrimination). This conceptualization of couple-level stress is distinct from relational stress as typically measured—with individual-level perceptions of their own experiences of relational conflict or satisfaction, for example—because it specifically focuses on stressors emanating from the stigmatization or marginalization of the relationship itself.

This extension of the minority stress framework is illustrated by Pathways 1 in Figure 3, which portrays this simple but important addition of couple-level stressors and how it may directly affect the mental health of each partner. The well-established individual-level minority stressors of stigma, discrimination and prejudice, internalized homophobia, and concealment are illustrated on the far left-hand side of the figure (Meyer, 1995, 2003a, 2003b); parallel conceptualizations of couple-level minority stressors are shown in the center. More generalizable couple-level stressors—outside of the minority stress domain (e.g., conflict, lack of trust, lack of desired intimacy)—are shown on the center of the right-hand side of the figure. Also on the right-hand side of the figure, indicators of individual partner mental health are portrayed as the ultimate outcomes, in accordance with the stress process model as originally conceived (Pearlin, 1999). We adopt a multi-outcome approach—including mood disorders, substance use/abuse, and suicide risk—because of subgroup differences in rates of particular mental health outcomes, for example, gender differences in rates of mood disorders (Aneshensel, 2005). Finally, as detailed below, we illustrate the reality of discrepancies in stress experience between partners on the left-hand side of the figure.

To increase the clarity of our theorizing about stress processes, we purposefully omit key elements of stress process models, namely variables that are likely to moderate or mediate effects of stress on mental health (e.g., psychosocial resources such as a sense of mastery, effective coping strategies, social supports) and the overarching social factors (e.g., sociodemographic variables such as age, gender, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, as well as social contextual factors such as neighborhood or geographic region of residence) that establish the larger contexts for all studies of social stress. In addition, we do not illustrate the presence of primary stress appraisals (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), which importantly shape individuals’ and couples’ subjective experiences of stress as well. Nonetheless, these variables are also essential to the conduct of all stress process theorizing and research.

Moreover, the passage of time is suggested at the bottom of Figure 3, and it is critical to consider changes over time with regard not only to stress experience but also to mental health. A long-standing body of research demonstrates that preexisting mental disorders and changes in mental health over time significantly influence stress processes and current mental health outcomes. Examinations of stress generation, which refers to the fact that individuals with a history of mental health problems are more likely to have encountered negative life events and experiences that contribute both to overall stress experience and subsequent mental health (Eberhart & Hammen, 2009; Hammen, 1991), are relevant and further inform this integrated stress model. This is especially true of stress-generation studies that have focused on depression among mothers and daughters (Hammen, Brennan, & Le Brocque, 2011; Hammen, Brennan, & Keenan-Miller, 2008; Hammen et al., 2011; Hammen et al., 2012), as well as within heterosexual marriages (Davila, Bradbury, Cohan, & Tochuk, 1997). Therefore, applications of this framework can address stress generation by controlling for the preexisting mental health of both individuals as well as for changes in stress experience and mental health for each over time.

We contend that the relational context of stress is, in and of itself, an important stress domain that has not been sufficiently conceptualized and measured in existing social stress scholarship. As shown in the center of Figure 3, couple-level minority stressors that partners individually or jointly experience as a direct result of being part of a same-sex couple are hypothesized to be key determinants of relational well-being and individual mental health and, to our knowledge, have been unexamined in stress research. To designate a minority stressor as “couple level” is to say that it comes about as a result of being in a socially marginalized relationship. To better illustrate, hypothetical couple-level minority stressors that parallel the established individual-level minority stressors are shown in Table 1; however, our assumption is that new—yet-to-be-identified—couple-level stressors will emerge from ongoing work.

Table 1.

Example Individual- and Couple-Level Indicators of Minority Stress

| Minority stressors | Individual level | Couple level |

|---|---|---|

| Stigma/expectations of rejection | Worries that employers will not hire a person they suspect or know to be gay/lesbian | Expectations that one’s colleagues would be uncomfortable being around a person and his or her same-sex partner at a work-related social event |

| Discrimination/prejudice | Being denied a promotion at work because of sexual orientation | Being excluded from family functions because siblings do not want their children to be around a same-sex couple |

| Internalized Homophobia | Feeling that one would prefer to be heterosexual | Believing that one’s same-sex relationship is less important or valuable to society than heterosexual relationships are |

| Concealment | Making efforts to hide one’s sexual orientation from my family/friends | Pretending that one’s same-sex partner is merely a roommate or friend when family/friends visit |

Dyadic Minority Stress Processes in Relational Context

The seemingly simplistic addition of couple-level minority stress constructs opens a window into a complex constellation of interrelated stressors. The identification of couple-level minority stressors provides a useful starting point for thinking about previously unexamined processes of stress proliferation. Minority stressors may proliferate from the individual to the couple level, and there may be a proliferation from status-based stressors to role-based stressors (e.g., minority stressors leading to other relational stressors). In the language of stress proliferation theory, couple-level minority stressors (e.g., status-based stressors associated with being in an intimate relationship that is socially stigmatized) might be understood as a primary source of stress that can proliferate to other relational stressors (e.g., role-based stressors associated with being a partner in an intimate relationship), thus seen as secondary stressors. (Although we focus here on relational stressors generally experienced within intimate relationships [e.g., conflict, lack of trust, lack of desired intimacy], role-based relational stressors might also include those stemming from stressful tasks or obligations within relationships, as was done in the well-established body of research concerning stress in informal caregiving relationships.) Frameworks such as this one are important for moving stress research forward in that they avoid the limitations of examining stressors that originate from one source or domain at a time (Wheaton et al., 2013). For example, much can be learned from the study of linkages between individual- and couple-level minority stressors and how these two domains of stress may interact to influence relational well-being and individual partner mental health.

As previous research has demonstrated, there is a direct relationship between individual-level exposure to minority stress and mental health among sexual minority persons. This association is illustrated in Figure 3 by the pathways linking each partner’s individual-level minority stress experience to his or her mental health outcomes over time (Pathways 2a), as well as to other relational stressors (Pathways 2b). Additional stress processes, each concerning dyadic minority stress processes in the relational context, have been greatly underexamined in the existing social stress literatures, and we discuss them next.

Minority Stress Discrepancies

First, among same-sex couples, minority stress proliferation is likely to occur in instances of stress discrepancies, or the degree to which individuals’ levels of stress experience vary in relation to those of a significant other (Lyons et al., 2002; Wight et al., 2006, 2007). Because stress within intimate partnerships is more than the sum of its two parts, it is important to understand how partners stand in relation to one another. For example, summing the degree to which two women involved in a same-sex relationship experience internalized homophobia—an individual-level minority stressor—would yield the total internalized homophobia burden for the pair, but that sum would not reflect the extent to which this burden is similarly experienced by each partner.

Indeed, if one partner has low levels of internalized homophobia relative to the other, stress may emerge from this discrepancy in multiple ways. For instance, it may become a source of relational conflict or a barrier to desired intimacy. In Figure 3, the dotted lines (labeled 3a) illustrate that discrepancies are borne out of differences between the two individuals’ unique experiences of minority stress. Dotted lines with arrows illustrating Pathways 3b and 3c for each partner provide a graphic representation of how discrepancies in minority stress experience between partners can influence their mental health directly (Pathway 3b) and via other relational stressors (Pathway 3c). In other words, we take into consideration each partner’s level of stress vis-à-vis that of her or his partner to learn about the impact of stress discrepancies on subsequent relational stressors and individual mental health.

Existing studies have assessed stress discrepancies, for example, those examining the convergence or divergence of stressful experience within caregiving dyads. However, such investigations have not assessed a wide range of stressors to which individuals in close relationships are jointly exposed. Instead, they have focused, for example, on caregiving relationship strain (Lyons et al., 2002), HIV-related stigma (Wight et al., 2006), and HIV-related uncertainty about the future (Wight et al., 2008). Little research has systematically examined the effects of stress discrepancies on the mental health of individuals in intimate relationships of any type. As shown in Figure 3, experiencing relatively greater or lesser levels of minority stress within the context of one’s intimate relationships represents an unexamined stress process that may uniquely contribute to sexual minority mental health. To the degree that discrepancies in additional domains of stress are assessed and studied in a diversity of populations, we stand to learn a great deal more about the relational context of stress.

Minority Stress Contagion

Figure 3 illustrates another form of minority stress proliferation. This concerns instances of minority stress contagion, whereby individual-level minority stressors faced by one partner intrude on the life of the other (Pathway 4a [dashed lines]). Most typically, stress contagion has been examined by focusing on the associations between each individual’s stress experience and the mental health of an intimate other, as shown in Pathways 4b. Such crossover or “partner” stress effects on mental health have been consistently demonstrated in existing investigations—some based on dyadic data—of individuals facing stressful circumstances or experiences in a relational context (Badr, Carmack, Kashy, Cristofanilli, & Revenson, 2010; Bolger et al., 1989a; Bolger, DeLongis, Kessler, & Wethington, 1989b; Falconier & Epstein, 2010; Lyons et al., 2002; Pearlin et al., 2005; Spanier, 1976; Townsend, Miller, & Guo, 2001; Wight et al., 2007, 2008).

Nonetheless, it will be helpful if future studies can build deeper understandings of the contagion of minority stress between persons within key relationships (Pathway 4a in Figure 3). For example, the degree to which a specific stressor (e.g., from among a range of minority stressors as they vary in proximity to the self, as shown in Figure 2) faced by one partner influences her or his loved one’s experience of the same or other stressors is not well understood. For instance, if a gay man holds a deep-seated belief that male couples should not be allowed to raise children together (a form of internalized homophobia), which leads him to consistently argue against the rights of same-sex couples to become parents, his feelings and actions may create ongoing stress and relationship strains for his partner. In turn, the partner might adopt the same stance against same-sex couples’ desires and efforts to have and raise children or, alternatively, he may come to vigilantly defend against his partner’s and others’ efforts to discourage or legally prohibit same-sex parenting.

This situation may present initially as a discrepancy in internalized homophobia, yet contagion is evident in the process by which one partner’s experience of internalized homophobia creates changes in the other partner’s experience of the same minority stressor. The mechanisms through which stressors become contagious are not well understood, and it is not known which stressors are most or least contagious between partners within the relational context—with those most contagious potentially having the potential to incur greater harm to individual mental health. The relationship between minority stress contagion and the creation of couple-level minority stress experience has yet to be examined (Pathways 4c in Figure 3).

Although we are focused here on discrepancies and contagion effects between partners, interactive effects might also identify scenarios in which partners with similar levels of given minority stressors affect one another’s stress processes in important ways, and these too should be considered. For example, two partners who are each very high or very low in terms of internalized homophobia might feed off of one another, further heightening or diminishing their individual experiences of internalized homophobia.

Stress Proliferation: Pathways Involving Multiple Domains of Stress

Beyond its focus on individual- and couple-level minority stressors this new framework supports the study of stress processes involving more generally experienced relational stressors (e.g., conflict, lack of trust, lack of desired intimacy), as illustrated with Pathway 5 in Figure 3. In doing so, we draw attention to the importance of simultaneously considering stressors that reflect multiple domains of stress, in this case, for example, by examining stressors associated with both status (e.g., sexual minority) and role (e.g., partner).

This integration of status- and role-based stress within the same framework represents a significant advance in stress process theory because it links the examination of stressors that are largely unique to socially disadvantaged populations (i.e., minority stress) to a set of stressors that are experienced in the general population. In particular, it facilitates a focus on the potential of couple-level minority stressors to act as critical agents of stress proliferation. In other words, couple-level minority stressors might be understood as a primary source of stress that can proliferate to other relational stressors, which in turn may affect relational well-being and individual partner mental health. Moreover, dyadic minority stress processes in the relational context—such as the convergence and divergence of stress—may pose additional challenges for same-sex couples (Pathways 3c and 4c–5 in Figure 3).

In particular, we focus on how couple-level minority stressors may expand or proliferate to influence indicators of relational well-being, such as relationship quality, including partners’ respective levels of conflict, sexual dysfunction, relationship dissatisfaction, lack of trust, and lack of desired intimacy in their relationship (Balsam & Szymanski, 2005; Frost & Meyer, 2009; Mohr & Daly, 2008; Otis, Rostosky, Riggle, & Hamrin, 2006). These indicators of relational well-being can be thought of as outcomes in their own right, but here we note how they constitute secondary stressors that are rooted in individuals’ roles as partners in romantic relationships. These secondary role-based stressors emanate from primary status-based minority stressors, and ultimately they compromise mental health.

One illustrative scenario would be a case in which a gay couple experiences stress because they feel certain that one partner’s family would reject them decide to hide their relationship from that partner’s family and others in their professional and social networks who might purposely or inadvertently “out” them as a couple. Such efforts to conceal their relationship create ongoing challenges with regard to when and where they can be comfortable interacting as a couple, expressing affection for one another, which can lead both partners to feel less satisfied with their relationship and less close to one another. In this scenario, a couple-level minority stressor (i.e., couple-level concealment) begets more stress through exacerbated relationship strains, which in turn can have negative mental health consequences for one or both partners (Berry & Worthington, 2001; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001). Much can be learned from studies of stress proliferation that more fully articulate and integrate multiple domains of stress (status and role based) in intimate relationships, both as outcomes influenced by important sources of stress and as subsequent determinants of well-being.

Discussion

Integrating concepts from stress proliferation and minority stress approaches leads us to conceive of and assess minority stress as it experienced both by and between individuals in their intimate relationships, yielding greater insights into previously undertheorized and unexamined forms and processes of minority stress. This extension of existing stress frameworks is valuable because it facilitates the study of stress processes that link individual- and couple-level experiences of stress. It also creates new possibilities for thinking about how stressors emanating from both status- (e.g., sexual minority) and role-based (e.g., partner) stress domains may be interrelated in ways that affect mental health over time.

Our articulation of couple-level minority stress represents two fundamental and distinct aspects of stress process in the relational context. First, couple-level minority stressors may arise directly from the stigmatized status of same-sex relationships, and such stressors may in turn affect relational well-being and individual mental health (see Figure 3, Pathways 1 and 5) above and beyond the individual-level minority stressors as experienced by either partner (see Figure 3, Pathway 2a). Second, dyadic minority stress processes, which result from the relational experience of individual-level minority stressors within couples—such as minority stress discrepancies and stress contagion—may also contribute to relational well-being and individual mental health (see Figure 3, Pathways 2b, 3a, 3b, 3c, 4a, and 4b).

Beyond Same-Sex Couples

As demonstrated above, such theorizing about processes of minority stress and stress proliferation may be especially fruitful to future research attempting to uncover unique social determinants of health within sexual minority populations (Institute of Medicine, 2011). Moreover, it has the potential to advance the study of relationships involving, and health among, individuals from other socially disadvantaged populations (e.g., racial/ethnic minorities). In particular, the framework can be applied to building better understandings of how minority stress is experienced by all individuals involved in intimate relationships where they and/or their partners become stigmatized by the social environment in which they live (i.e., marginalized relationships; Lehmiller & Agnew, 2006).

Other marginalized relationships to which this integrated framework can be fully applied include interracial/ethnic couples. To illustrate, consider a marriage between an African American man and a non-Hispanic White woman. This couple may experience couple-level minority stress because interracial/ethnic romantic relationships remain stigmatized in many settings (e.g., Bratter & King, 2008). For example, the couple may individually and jointly experience minority stressors (e.g., facing disapproval when showing affection for one another in public, or being discouraged from having children by relatives or friends). Second, the man’s individual-level experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination may also present challenges for the couple in the form of dyadic minority stress processes, because they are discrepant in their experiences of minority stress as individuals (e.g., he experiences discrimination on the basis of his race/ethnicity, whereas she does not). She may experience individual-level minority stress in the form of race-based rejection from members of her husband’s African American family, further illustrating how stigmatized statuses may be acquired in the context of intimate relationships (Frost, 2011b). Such dyadic minority stress processes, as conceived of here, are inherently rooted in the social role of spouse or intimate partner, and occupancy in this role shapes stress experiences at the individual and couple levels, carrying on the role-based focus of past stress-proliferation studies (e.g., Pearlin et al., 1997) within the context of minority stress.

In addition, integrated stress frameworks that simultaneously examine stress associated with both statuses and roles may be usefully applied to the study of relational well-being and health among some interfaith couples, as well as age-discrepant couples in whom the older partner faces age-based stigma or discrimination (Lehmiller & Agnew, 2006). They may also be applied to couples in whom one partner lives with a stigmatizing disability or health-related condition that results in his or her experience of individual-level minority stressors that then creates dyadic minority stress processes whereby the relationship itself is marginalized in some way (e.g., one partner is HIV positive and the other is HIV negative). Indeed, in each of these examples the relationship itself is socially stigmatized and at least one partner faces unique stressors as a marginalized individual (e.g., based on race/ethnicity, religion, age, and health status/disability).

Moreover, such integrated stress frameworks may also be applicable, in part, to the study of other kinds of relationships, including instances in which the relationship itself is not a source of stigma and discrimination, unlike the examples above, for which one can observe the sharing of couple-level minority stressors. To illustrate, among heterosexual couples in whom both partners are Mexican American, the relationship itself is typically socially sanctioned and supported, but each partner may experience minority stress associated with his or her racial/ethnic minority status. Those individual-level minority stressors may have negative effects not only on the quality of their relationship (e.g., Doyle & Molix, 2014) but also on the health of each partner through dyadic minority stress processes rooted in stress discrepancies and stress contagion. Although a large body of research has examined the effects of racial/ethnic discrimination on individuals’ health and well-being (e.g., Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009), the framework extends this line of research to investigate how varying experiences of discrimination affect not only one’s own health but also the health of his or her partner.

Despite our efforts to extend existing stress theory by integrating status- and role-based stressors, and expanding current conceptualizations and applications of couple-level stress, the reality of relational stress is of course far more complex than portrayed here. To explain the promise of our current approach, we have selectively focused on specific relationship types defined by one marginalized social status, yet in reality individuals often occupy—and their intimate relationships often represent—multiple marginalized statuses. To illustrate, same-sex couples in whom at least one partner is a person of color may contend with challenges stemming from both sexual orientation and racial/ethnic identity. In interracial or interethnic heterosexual couples, both partners may experience racial/ethnic minority stress and the woman may face gender-based discrimination. Thus, future studies must also address the intricacies of studying the intersectionality of multiple disadvantaged statuses—within individuals and within dyads—in the evolving study of social stress, relationships, and health (cf. Cole, 2009; Grollman, 2012, 2014).

Finally, looking beyond the intimate dyad, future researchers may also adopt a family systems perspective (cf. Miller, Anderson, & Keala, 2004) to this integrated stress framework. For example, such application could lead to new understandings of how the effects of racial/ethnic minority stress experienced by a child in an African American family (individual-level minority stress) and by both parents (couple-level minority stress) may become intertwined in a larger constellation of stressors—minority and other—that affect the well-being of all family members. Thus, we are also further challenged to simultaneously examine minority stress processes in additional roles, role sets, and family systems.

Methodological Implications

Building on two well-established conceptualizations of social stress—stress proliferation and minority stress—we offer a new theoretical framework for deepening current understandings of well-being among same-sex and other marginalized couples. The centerpiece of this framework is the introduction of couple-level minority stressors, which we hypothesize play an important role in determining relationship quality and mental health for individuals in same-sex couples. Processes of stress proliferation rooted in relational dynamics involving both individual- and couple-level minority stressors have not been examined in existing stress scholarship, and below we discuss some implications for future studies that attempt to fill this void.

The conceptualization of couple-level stress introduces methodological challenges associated with developing new stress measures that lend themselves to true joint assessments, completed by partners working together as a couple to provide data regarding their shared experiences of stress. Such joint assessments may be most likely applied to the measurement of stressors that can be more objectively measured, for example—continuing with the example of sexual minority stressors—events involving discrimination (e.g., when a couple is verbally harassed or threatened when expressing affection in public). Additional objective couple-level assessments may include shared contextual variables indicative of structural factors relevant to minority stress, such as state-level marriage policies and proximity to other same-sex couples (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2010).

Although couple-level minority stress constructs represent shared experiences between partners, survey measures of couple-level stressors will continue to be most typically completed by individuals. Therefore, novel couple-level stressor measures must be distinguished for their utility in assessing each partner’s perceptions about stressors inherently tied to their couple-level minority status as well as about stressors that are jointly experienced with a partner. To illustrate, first-person singular referents will be useful if they capture an individual’s feelings or experiences relating to his or her same-sex relationships, for example, “I never talk about my partner with my relatives because I don’t want to make them feel uncomfortable.” With regard to stressors that are shared by couples, this can be achieved through questions framed with first-person collective referents, such as “We have taken steps to make sure visitors to our home cannot tell that we are a couple,” which would serve as an example of couple-level concealment of the relationship. The framing of this question requires each member of the couple to evaluate the shared nature of this couple-level minority stressor. Each individual’s rating of a diverse range of couple-level stressors can then be modeled as an indicator of a latent construct of couple-level minority stressors using latent variable modeling techniques within a structural equation modeling approach. This has been referred to as the common fate modeling approach to accounting for couple-level constructs in dyadic research (Ledermann & Kenny, 2012).

Moreover, existing analytical frameworks and statistical techniques can be adapted to specify and test the different forms of stress proliferation illustrated in Figure 3 and described earlier in this article. Kenny and colleagues (e.g., Cook & Kenny, 2005) have developed a flexible model for dyadic analysis, called the actor–partner interdependence model (APIM), which can be used to disentangle the various effects of a diverse constellation of stressors—representing both individual- and couple-level stress constructs as well as status- and role-based stress domains—to examine the mental health effects of stress proliferation. Within the APIM, actor effects represent the effects of each partner’s individual experience of minority stress on his or her own mental health (see Figure 3, Pathway 2a). The strength of these actor effects can then be compared to partner effects, which can in turn be used to model the proliferation of stressors. Partner effects, in essence, reflect the effect of one partner’s individual minority stress on his or her partner’s mental health (see Figure 3, Pathway 4b). The APIM is flexible enough to handle mediated pathways as well. When modeled as a dyadic latent variable using a common fate model, a mediated pathway linking individual-level minority stress to couple-level minority stress to relational well-being and mental health (see Figure 3, combined Pathways 4c and 1) could be tested whereby couple-level minority stress mediates both actor and partner effects of individual-level minority stress on relational well-being and mental health. Stress contagion would be evident in mediated partner effects, whereby Partner A’s experience of an individual-level minority stress affects Partner B’s experience of that same stress, which in turn affects Partner B’s mental health (see Figure 3, combined Pathways 4a and 2a).

A more complex causal pathway involving other relational stressors (e.g., conflict, lack of trust, lack of desired intimacy) as a second mediating variable could also be tested to illustrate the ways in which individual- and couple-level minority stressors proliferate into the more general domain of relational stress, which in turn affects the mental health of both partners (see Figure 3, combined Pathways 4c and 5). Finally, the APIM can handle multiplicative interaction terms, which can be modeled to reflect the role that stress discrepancies between partners play as dyadic minority stress processes affecting relational well-being and mental health (see Figure 3, Pathways 3b and 3c).

In addition, qualitative studies of couple-level stress experience will be important. Adaptations of existing qualitative research methods designed for use with individuals to the study of dyads hold particular promise, for instance, lifeline studies, which grow out of the life course and life events research traditions and are used to elicit narratives about the most significant events and periods of time over the course of one’s life. Lifeline scholarship fosters greater insight into the subjective meaning of the life events to the individuals who experience them (de Vries, Blando, Southard, & Bubeck, 2001; de Vries, Blando, & Walker, 1995). Adapting such a method to assess couple-level stress by creating a relationship timeline approach, in which couples jointly construct a graphic illustration of their relationship—past, present, and future—as a tool to elicit detailed discussions of the most significant events and periods through which they have jointly navigated, is just one example. The resulting narratives concerning events or periods that have been stressful for couples should prove to be useful in the development of couple-level stress measures. They also may be useful in developing deeper understandings of interpersonal stress processes (e.g., stress discrepancies and stress contagion) that emerge in intimate relationships during challenging times.

Indeed, qualitative inquiry in general stands to contribute greatly in the application of existing and new methods that allow for more nuanced understandings of what individuals and couples think and feel as they navigate the shared nature of stress intrapersonally, interpersonally, and within the larger social contexts that surround them. For example, beyond the identification of particular stress discrepancies within couples, researchers must work toward better understandings of the degree to which those discrepancies do or do not matter to each partner and to their relationship. For example, it is important to know how people individually and jointly make primary appraisals (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) about potentially stressful events or circumstances they share, as well as how they make sense of—find meaning in—relational stress experiences (cf. Frost, 2011b; McLeod, 2012). Moreover, innovative qualitative work could similarly examine their experiences of coping and accessing different sources of social support in the face of couple-level minority stress. Again using the example of identifiable stress discrepancies within couples, it will be important to learn more about how partners attempt to create strategies for jointly managing those discrepancies.

The Potential of Integrated Stress Frameworks

The conceptualization of social stress as a process allows us to think about how stressors that originate in one domain of life can expand and proliferate to create stress in other domains. Using this theoretical frame of reference, we link some of the struggles that sexual minority persons face, as individuals and as couples, in pursuing their hopes and aspirations for developing strong and personally rewarding intimate relationships that are socially valued and validated (Frost, 2011a, 2011c). Often their pursuits take place in climates where such relationships are publicly questioned and devalued. For example, debates about the legalization of same-sex marriage and adoptive parenthood for sexual minorities are ongoing and will continue to call into question the social value of same-sex partnerships.

With the Supreme Court’s recent decisions to reject the federal Defense of Marriage Act and decline further ruling on California’s Proposition 8, which in effect removed the ban on same-sex marriages in that populous state, the social climate navigated by sexual minorities will continue to shift as they persevere in their efforts to seek relational intimacy, form lasting partnerships, and raise children. The current historical moment draws attention to the reality that same-sex couples have always faced, and will continue to face, great opposition to achieving these basic relational pursuits. Stress process research, which is inherently focused on examining difficulties in achieving “ordinary pursuits of life … driven by widely shared values and commitments” (Pearlin, 1999, p. 396), such as the desire for intimate relationships and the roles and obligations associated with them, is uniquely well suited to furthering understandings of how such opposition affects the well-being of sexual minorities. In this way, stress process studies are tied to classic sociological theory, such as Merton’s (1938) contention that anomie is fundamentally rooted in disparities between aspirations that are socially normative and actual opportunities to fulfill those aspirations, which are also socially structured. However, scholarship that examines relational pursuits (Frost & LeBlanc, 2014), relationship status, and mental health among sexual minorities is only now beginning to emerge (Maisel & Fingerhut, 2011; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2010; Riggle, Rostosky, & Horne, 2010; Wight et al., 2012; Wight, LeBlanc, & Badgett, 2013). Given that same-sex couples will likely continue to be socially stigmatized after discriminatory policies have been addressed—just as interracial/ethnic couples continue to be stigmatized after the repeal of U.S. anti-miscegenation laws in 1967—our proposed couple-level minority stress framework will likely prove useful in research and interventions focused on mental health in marginalized relationships for some time to come.

Concluding Comments

This integration of two largely isolated theoretical approaches—stress proliferation and minority stress theory—holds great potential to deepen existing understandings of the relational context of stress experience and mental health across diverse populations, relationship types, and family forms. Moreover, with the identification of previously unexamined stressors and stress processes affecting the well-being of minority and nonminority populations through mechanisms of stress proliferation, this new framework will contribute to the development of more effective interventions designed to promote individual mental health in the context of intimate and other close relationships.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 1R01HD070357 (Allen J. LeBlanc, Principal Investigator). We thank Leonard Pearlin and Melissa Milkie for their helpful feedback on this article.

References

- Almeida DM, Wethington E, Chandler AL. Daily transmission of tensions between marital dyads and parent–child dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:49–61. doi: 10.2307/353882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS. Research in mental health: Social etiology versus social consequences. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46:221–228. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS. Neighborhood as a social context of the stress process. In: Avison WR, Aneshensel CS, Schieman S, Wheaton B, editors. Advances in the conceptualization of the stress process: Essays in honor of Leonard I. Pearlin. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2010. pp. 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Zarit SH, Whitlatch CJ. Profiles in caregiving: The unexpected career. New York: Academic Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Badr H, Carmack CL, Kashy DA, Cristofanilli M, Revenson TA. Dyadic coping in metastatic breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2010;29:169–180. doi: 10.1037/a0018165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Szymanski DM. Relationship quality and domestic violence in women’s same-sex relationships: The role of minority stress. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29:258–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00220.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Worthington EL. Forgivingness, relationship quality, stress while imagining relationship events, and physical and mental health. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2001;48:447–455. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.48.4.447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G. Dyadic coping and its significance for marital functioning. In: Revenson TA, Kayser K, Bodenmann G, editors. Couples coping with stress: Emerging perspectives on dyadic coping. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G, Cina A. Stress and coping among stable-satisfied, stable-distressed and separated/divorced Swiss couples: A 5-year prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage. 2005;44:71–89. doi: 10.1300/J087v44n01_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G, Ledermann T, Bradbury TN. Stress, sex, and satisfaction in marriage. Personal Relationships. 2007;14:551–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00171.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G, Meuwly N, Kayser K. Two conceptualizations of dyadic coping and their potential for predicting relationship quality and individual well-being: A comparison. European Psychologist. 2011;16:255–266. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G, Pihet S, Kayser K. The relationship between dyadic coping and marital quality: A 2-year longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:485–493. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, DeLongis A, Kessler RC, Wethington E. The contagion of stress across multiple roles. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1989a;51:175–183. doi: 10.2307/352378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, DeLongis A, Kessler RC, Wethington E. The microstructure of daily role-related stress in married couples. In: Eckenrode J, Gore S, editors. Crossing the boundaries: The transmission of stress between work and family. New York: Plenum Press; 1989b. pp. 95–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bratter JL, King RB. But will it last?: Marital instability among interracial and same-race couples. Family Relations. 2008;57:160–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00491.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun M, Scholz U, Bailey B, Perren S, Hornung R, Martin M. Dementia caregiving in spousal relationships: A dyadic perspective. Aging & Mental Health. 2009;13:426–436. doi: 10.1080/13607860902879441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen YF, Kogan SM, Murry VM, Logan P, Luo Z. Linking perceived discrimination to longitudinal changes in African American mothers’ parenting practices. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:319–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00484.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks V. Minority stress and lesbian women. Lexington, KY: Lexington Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist. 2009;64:170–180. doi: 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook WL, Kenny DA. The actor–partner interdependence model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29:101–109. doi: 10.1080/01650250444000405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Bradbury TN, Cohan CL, Tochuk S. Marital functioning and depressive symptoms: Evidence for a stress generation model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:849–861. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.4.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries B, Blando JA, Southard P, Bubeck C. The times of our lives. In: Kenyon G, Clark P, de Vries B, editors. Narrative gerontology: Theory, research, and practice. New York: Springer; 2001. pp. 137–158. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries B, Blando J, Walker LJ. The review of life’s events: Analyses of content and structure. In: Haight BK, Webster JD, editors. The art and science of reminiscing: Theory, research, methods, and applications. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis; 1995. pp. 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- DiPlacido J. Minority stress among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: A consequence of heterosexism, homophobia, and stigmatization. In: Herek GM, editor. Stigma and sexual orientation: Understanding prejudice against lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 138–159. [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP. The role of adversity and stress in psychopathology: Some evidence and its implications for theory and research. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DM, Molix L. Love on the margins: The effects of social stigma and relationship length on romantic relationship quality. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2014;5:102–110. doi: 10.1177/1948550613486677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart NK, Hammen CL. Interpersonal predictors of stress generation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2009;35:544–556. doi: 10.1177/0146167208329857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconier MK, Epstein NB. Relationship satisfaction in Argentinean couples under economic strain: Gender differences in a dyadic stress model. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2010;27:781–799. doi: 10.1177/0265407510373260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM. Similarities and differences in the pursuit of intimacy among sexual minority and heterosexual individuals: A personal projects analysis. Journal of Social Issues. 2011a;67:282–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01698.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM. Social stigma and its consequences for the socially stigmatized. Social & Personality Psychology Compass. 2011b;5:824–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00394.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM. Stigma and intimacy in same-sex relationships: A narrative approach. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011c;25:1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0022374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, LeBlanc AJ. Nonevent stress contributes to mental health disparities based on sexual orientation: Evidence from personal projects analysis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84:557–566. doi: 10.1037/ort0000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, Meyer IH. Internalized homophobia and relationship quality among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:97–109. doi: 10.1037/a0012844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, Parsons JT, Nanín JE. Stigma, concealment and symptoms of depression as explanations for sexually transmitted infections among gay men. Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;12:636–640. doi: 10.1177/1359105307078170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Walsemann KM, Brondolo E. A life course perspective on how racism may be related to health inequities. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:967–974. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grollman EA. Multiple forms of perceived discrimination and health among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2012;53:199–214. doi: 10.1177/0022146512444289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grollman EA. Multiple disadvantaged statuses and health: The role of multiple forms of discrimination. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2014;55:3–19. doi: 10.1177/0022146514521215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG, Almeida DM, McDonald DA. Work–family spillover and daily reports of work and family stress in the adult labor force. Family Relations. 2002;51:28–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2002.00028.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. The generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:555–561. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Brennan PA, Keenan-Miller D. Patterns of adolescent depression to age 20: The role of maternal depression and youth interpersonal dysfunction. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:1189–1198. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Brennan PA, Le Brocque R. Youth depression and early childrearing: Stress generation and intergenerational transmission of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:353–363. doi: 10.1037/a0023536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Hazel NA, Brennan PA, Najman J. Intergenerational transmission and continuity of stress and depression: Depressed women and their offspring in 20 years of follow-up. Psychological Medicine. 2011;42:931–942. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. State-level policies and psychiatric morbidity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:2275–2281. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:452–459. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Erickson SJ. Minority stress predictors of HIV risk behavior, substance use, and depressive symptoms: Results from a prospective study of bereaved gay men. Health Psychology. 2008;27:455–462. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igartua KJ, Gill K, Montoro R. Internalized homophobia: A factor in depression, anxiety, and suicide in the gay and lesbian population. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 2003;22:15–30. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2003-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton TL. Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc AJ, Aneshensel CS, Wight RG. Psychotherapy use and depression among AIDS caregivers. Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23:127–142. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc AJ, London AS, Aneshensel CS. The physical costs of AIDS caregiving. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;45:915–923. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledermann T, Bodenmann G, Rudaz M, Bradbury TN. Stress, communication, and marital quality in couples. Family Relations. 2010;59:195–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00595.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ledermann T, Kenny DA. The common fate model for dyadic data: Variations of a theoretically important but underutilized model. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26:140–148. doi: 10.1037/a0026624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K, Simoni JM. The impact of minority stress on mental health and substance use among sexual minority women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:159–170. doi: 10.1037/a0022839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmiller JJ, Agnew CR. Marginalized relationships: The impact of social disapproval on romantic relationship commitment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:40–51. doi: 10.1177/0146167205278710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons KS, Zarit SH, Sayer AG, Whitlatch CJ. Caregiving as a dyadic process: Perspectives from caregiver and receiver. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57B:195–204. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.3.P195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisel NC, Fingerhut AW. California’s ban on same-sex marriage: The campaign and its effects on gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Social Issues. 2011;67:242–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01696.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1869–1876. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.11.1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod JD. The meanings of stress: Expanding the stress process model. Society and Mental Health. 2012;2:172–186. doi: 10.1177/2156869312452877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK. Social structure and anomie. American Sociological Review. 1938;3:672–682. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice as stress: Conceptual and measurement problems. American Journal of Public Health. 2003a;93:262–265. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003b;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]