Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the evidence on the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for improving pregnancy rates and reducing distress for couples in treatment with assisted reproductive technology (ART).

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

PsycINFO, PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, Web of Science and The Cochrane Library between 1978 and April 2014.

Study selection

Studies were considered eligible if they evaluated the effect of any psychosocial intervention on clinical pregnancy and/or distress in infertile participants, used a quantitative approach and were published in English.

Data extraction

Study characteristics and results were extracted and the methodological quality was assessed. Effect sizes (ES; Hedges g) were pooled using a random effects model. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Q statistic and I2, and publication bias was evaluated using Egger’s method. Possible moderators and mediators were explored with meta-analyses of variances (ANOVAs) and meta-regression.

Results

We identified 39 eligible studies (total N=2746 men and women) assessing the effects of psychological treatment on pregnancy rates and/or adverse psychological outcomes, including depressive symptoms, anxiety, infertility stress and marital function. Statistically significant and robust overall effects of psychosocial intervention were found for both clinical pregnancy (risk ratio=2.01; CI 1.48 to 2.73; p<0.001) and combined psychological outcomes (Hedges g=0.59; CI 0.38 to 0.80; p=0.001). The pooled ES for psychological outcomes were generally larger for women (g: 0.51 to 0.73) than men (0.13 to 0.34), but the difference only reached statistical significance for depressive symptoms (p=0.004). Meta-regression indicated that larger reductions in anxiety were associated with greater improvement in pregnancy rates (Slope 0.19; p=0.004). No clear-cut differences were found between effects of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT; g=0.84), mind–body interventions (0.61) and other intervention types (0.50).

Conclusions

The present meta-analysis suggests that psychosocial interventions for couples in treatment for infertility, in particular CBT, could be efficacious, both in reducing psychological distress and in improving clinical pregnancy rates.

Keywords: Infertility, Psychosocial intervention, distress, pregnancy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A major strength of this study is the extensive search of various databases from 1978 to April 2014, as well as a comprehensive methodological assessment.

Further analyses were performed to account for publication bias, yielding conservative effect sizes and thus strengthening the robustness of the estimates.

Heterogeneity and indications of publication bias were observed for several of the outcomes.

A substantial variation of the methodological quality and missing information on fertility and assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment may limit the interpretability of the outcomes.

Introduction

Fecundity has become a growing problem for many couples trying to conceive a child, and although not all couples choose to seek medical assistance, more than 10% of the childbearing population has resorted to assisted reproductive technology (ART) to conceive.1–5 Being involuntarily childless and going through various ART procedures imposes considerable stress on the couple, and childlessness is often perceived as a life crisis where the emotional strain equals that found for traumatic events.2 6–10 Although infertile couples may be considered mentally healthy in general,11 several studies indicate that coping with infertility is associated with periodically heightened levels of psychological symptoms of distress, depression and anxiety.12 13 Feelings of loss, grief, anger and sadness are not uncommon, and women often report bodily disparagement, lack of femininity, shame and self-blame.2 14 There is some evidence to suggest that dysregulation in the uterus microenvironment may influence the ability to conceive, for example, oxidative stress and inflammation,15 16 which may be promoted by psychological distress.17 18 Such findings have led several studies to investigate possible links between mental state and pregnancy outcome.10 19–24 Although the results have been mixed, reviews of the literature have generally reached the conclusion that psychosocial factors such as depressive symptoms, anxiety, distress and certain coping strategies are linked to reduced chances of pregnancy.12 25 26 Two recently published meta-analyses, however, report conflicting results.27 28 Whereas one meta-analysis supported the conclusion that emotional distress may be critical to the success of fertility treatment outcome,27 the other did not find sufficient support for this hypothesis.28 The different conclusions could be due to between-study methodological differences, for example, in the chosen measures of distress and definitions of pregnancy (eg, serum positive test, clinical pregnancy or live birth).

Nonetheless, the evidence indicating a considerable psychosocial burden associated with infertility and its treatment has inspired several researchers to explore the effect of various psychosocial interventions in reducing distress, improving quality of life, and thereby possibly optimising the chances of pregnancy. So far, three meta-analyses have reviewed effects of psychological interventions on mental health and pregnancy outcome. Again, the results have been mixed. The first meta-analysis, published in 2003, concluded that psychological intervention appeared to have a beneficial effect on negative emotions,29 particularly anxiety. An effect of counselling was also found for infertility-related distress, whereas no clear effect was seen on pregnancy rates. Although the original systematic review identified 25 independent studies, the final meta-analysis only included 8–10 studies selected on the basis of their methodological quality. The second meta-analysis published in 2005 focused on differences in effects related to intervention format, for example, individual/couple versus group setting.30 Overall, the results suggested that both individual/couple and group interventions were effective in reducing emotional distress as well as increasing the conception rate. In contrast to the two first meta-analyses, which had investigated both controlled and uncontrolled studies, the third meta-analysis from 2009, which only included controlled studies,31 found no evidence for an effect of psychological interventions on emotional distress. An effect, however, was found for pregnancy rates, but only for infertile couples not in ART.

Taken together, while showing promising results, the findings of existing quantitative systematic reviews, the most recent published in 2009, are mixed. The literature within this field is expanding, and studies of new psychosocial intervention approaches building on existing knowledge and targeting specific problems of infertile patients, for example, mind/body interventions (MBIs), internet-based treatments and online psychoeducation programmes, have since been published. Furthermore, the more recently published studies have generally used randomised controlled trial (RCT) designs, a notable strength reducing the risk of bias and making the studies more easily comparable.32 An updated review and meta-analysis is needed to determine to what degree psychosocial interventions may reduce infertility-related distress related to improvement of pregnancy chances during fertility treatment.

Methods

The present study was conducted in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) recommendations.33 34 An a priori designed study protocol guided the literature search, study selection and data synthesis.

Search strategy and criteria

A comprehensive and systematic search of the literature published between 1978 (first baby born after in vitro fertilisation (IVF)) and April 2014 was conducted, using a sensitive search strategy recommended for reviews by Higgins and Green.35 When conducting the searches, we combined keywords representing the two primary concepts, infertility and psychosocial treatment: (1) “infertil*”, “childlessness”, “IVF”, “ICSI”, “fertility treatment/problems” “assisted reproduction” and (2) “psychological/psychosocial intervention”, “social support”, “couples therapy”, “psycho-education”, “internet-based intervention” and “behavioral therapy” (for a full search history, see online supplementary appendix 1). We identified relevant records by electronic searches in general medical and psychological databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, The Cochrane Library, EMBASE, CINAHL and Web of Science. Furthermore, we cross-examined reference lists of the retrieved papers and reviews for additional relevant studies. We did not pursue the grey literature or trial registries, and limited our search to include only peer-reviewed articles published in English.

Study selection

Studies were considered eligible if they (1) reported data on infertile participants (2) presented data on a psychosocial intervention or a supportive programme (3) included baseline and postintervention measures of stress, distress or pregnancy outcome and (4) used a quantitative research approach. In general terms, infertility refers to not being able to conceive for more than 1 year without contraception (WHO, 2002). Despite this standard definition, a recent review has found considerable between-study variation in definitions.36 Furthermore, infertility can be graded in relation to clinical diagnosis and duration. The present meta-analysis reviews studies using several different definitions of the term ‘infertile’, and includes all studies of patients diagnosed with different types of infertility and in different types and stages of ART treatments, for example, intrauterine insemination (IUI), IVF and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). ‘Psychosocial interventions or supportive programs’ were defined as all interventions with a psychosocial aim that did not include the prescription of medication or had a primary physical focus, for example, acupuncture or massage therapy. However, studies using ‘psychophysiological’ approaches, for example, relaxation, guided imagery or meditation exercises as part of a psychosocial programme, were included. The interventions could be delivered in an individual-based, group-based, couples-based or internet-based format. We included controlled and uncontrolled trial (UCT) studies, but chose to exclude expert opinion, magazines, commentaries, case reports, editorials, newspaper articles, newsletters and book chapters. Neither did we include abstracts-only, doctoral theses or conference presentations. Our primary outcome was pregnancy rate, defined as clinical pregnancy. This clinical definition implies a visualisation of at least one gestational sac and fetal heartbeat in approximately the fifth week after fertilisation. Secondary outcome measures were psychological ratings of depressive symptoms, anxiety, generalised stress, specific infertility stress and interpersonal functioning assessed through self-reported questionnaires.

Data extraction and quality assessment

All full-text articles were read by two independent review authors (IF-V, NGS) and the data were extracted according to predefined criteria. Disagreements were discussed with a third author (YF) and resolved by consensus. If information on any outcome was missing or if clarifications were needed, authors were contacted for further information. Each study was assessed for methodological quality using the Jadad criteria,37 a commonly used tool to evaluate methodological quality, for example, use and adequate description of randomisation and blinding procedures, and description of dropout rates (score range 0–5). In addition to the 0–5 points possible on the original Jadad scale, 1 additional point was given for each of the following: (1) was a control group included, in order to acknowledge whether the intervention group was compared with another group, although randomisation was not used; (2) were both predata and postdata presented, as including preintervention and postintervention data will provide more accurate results; (3) was any form of blinding or masking of conditions to patients or (4) blinding of researchers attempted, acknowledging if the study had attempted to mask the active condition; (5) was a standardised and reliable outcome measure used, a criterion increasing the validity and comparability of the outcomes and (6) were pre–post correlations provided, which could provide better estimates of the effect size (ES). The modified scale yielded a total quality score ranging from 0 to 11. With respect to the modified quality score, the mean score difference between rater 1 and 2 (means (SD) 5.2 (1.8) and 5.6 (2.0)) did not reach statistical significance (t (77)=1.1; p=0.28), and the inter-rater score correlation was r=0.83 (p<0.001). The κ Statistic was not used, as this assumes the nominal data and no natural ordering of ratings. Quality ratings were not used as weights when calculating aggregated ES as this is generally discouraged due to the risk of introducing additional bias.38 Instead, associations between ES and study quality indicators were explored with meta-analyses of variances (ANOVAs) and meta-regression (modified quality score). In cases where we were unable to retrieve articles from the authorised databases, authors were contacted between 1 and 3 times in order to amend the data collected.

Calculating ES

The ES used were the risk ratio (RR) for pregnancy and Hedges g for psychological outcomes. Hedges g is a variation of Cohen's d which enables correction of potential bias due to small sample sizes.39 40 A positive Hedges g indicates a result in the expected direction, for example, a reduction in distress in the intervention group compared with controls. An RR>1.0 indicates a greater proportion of pregnancies in the intervention group. RRs were based on pregnancy rates and total N in the intervention and control groups. When possible, Hedges g was calculated on the basis of reported means and SDs at preintervention and postintervention or means and SDs of change scores. This was possible for 50 of 61 ES. When required and available, the reported pre–post correlations were used in the calculation. This was the case for five ES. When unavailable, the pre–post correlation was set to 0.50. When SDs were unavailable, two approaches were used. For STAI (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory) state anxiety scores, the average pre-SDs and post-SDs (10.9 and 10.8, respectively) for the studies which reported the SD were used, as the SDs appeared to be highly comparable across the remaining studies. For other measures, ES were estimated either on the basis of sample size and either p value or η2. In one study reporting only medians,41 the means and SDs were estimated following a previously suggested approach.42

Heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was assessed using Q and I² statistics. Heterogeneity tests are aimed at determining whether results reflect genuine between-study differences (heterogeneity), or whether the variation is due to chance (homogeneity).43 In accordance with recommendations, a p value ≤0.10 was used to determine significant heterogeneity due to the general low statistical power of heterogeneity tests.44 The I2 quantity provides a measure of the degree of inconsistency by estimating the amount of variance in a pooled ES that can be accounted for by heterogeneity in the sample of studies.45 I2 values of 0%, 25%, 50% and 75% indicate no, low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively.

Analytical strategy

All ES were weighted with the inverse variance and combined with a random effects model. First, the overall ES of the effect of psychosocial interventions on pregnancy rates was calculated. Then the overall ES for the combined psychological outcomes was calculated together with the overall ES for the individual outcome measures of depression, state anxiety, infertility-related distress and marital function. This was performed for the combined sample (women+men). If the results indicated study heterogeneity, and if the number of studies in each category was sufficient (K≥3), possible between-study differences in ES were explored by comparing the ES of studies according to the following study characteristics: gender, study design, intervention type and intervention format (mixed effect meta-ANOVAs), methodological quality (modified quality score), mean age of the sample, intervention duration and number of sessions (mixed effect meta-regression).

Prior to the search, statistical power analyses were conducted as previously recommended.46 On the basis of the findings of the earlier meta-analysis,31 we expected to find an RR of 1.4 for pregnancy rates and an average sample size of N=76. We expected to be able to detect a similar small ES (Hedges g=0.28 or RR=1.4) with an α of 5% and a statistical power of 80%, with a total of only nine studies, using a random effects model. On the basis of these results, we considered it worthwhile to conduct the meta-analysis. The calculations were conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis, V.2 (http://www.meta-analysis.com), IBM SPSS V.20 and various formulas in Microsoft Excel.

Publication bias

The possibility of publication bias, a widespread problem when conducting meta-analyses, was evaluated with funnel plots,47 Egger's method and by calculating fail-safe numbers.48 49 A funnel plot is a graphic illustration of study ES in relation to study size or precision. Egger's test provides a statistic for the skewness of results.50 Calculation of fail-safe numbers is aimed at achieving an indication of the number of unpublished studies with null findings that would reduce the result to statistical non-significance (p>0.05). It has been suggested that a reasonable level is achieved if the fail-safe number exceeds 5K+10 (K=N studies in the meta-analysis).51 If the results were suggestive of publication bias, an adjusted ES was calculated using Duval and Tweedie's52 trim and fill method, which imputes ES of missing studies and recalculates the ES accordingly.

Results

Study selection

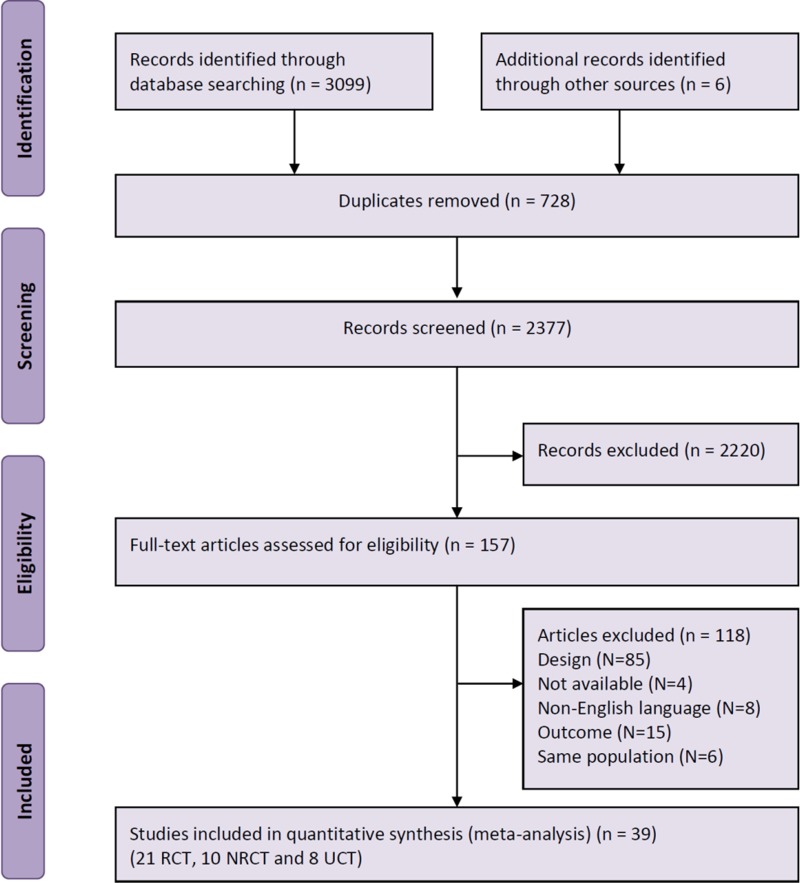

In a first screening, duplicates were identified, and titles and abstracts reviewed. A total of 157 studies were found potentially relevant and reviewed independently by two raters. Four articles could not be retrieved due to the ‘no access policy from the university, and the authors did not respond to our enquiries.53–56 Initially, the raters were uncertain or disagreed on 13 (8.3%) articles (inter-rater agreement 0.78; p<0.001 (κ statistic)) indicating ‘substantial agreement’.57 After negotiation, 5 of these were included, resulting in 41 potentially eligible articles. One additional study was excluded due to the combination of psychological intervention with a psychoactive drug, and one study had insufficient statistical data and the authors did not respond to our enquiry. We thus included a total of 39 studies in the present review. On three occasions, the authors provided unpublished additional data.58–60 Figure 1 shows a flow chart of the study selection process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of selection of studies (NRCT, non-randomised controlled trial; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; RCT, randomised controlled trial; UCT, uncontrolled trial).

Study characteristics

The study characteristics are summarised in table 1. Based on the outcome, 29 of the studies were aimed at reducing negative emotional distress,41 58–85 with the targeted outcomes being infertility-related distress (k=10), depression (k=21), anxiety (k=25) and marital function (k=5). Five studies focused solely on the outcome of pregnancy,86–90 and five had included distress as well as pregnancy as the outcome.78 91–94 Twenty-one studies were RCTs,58 61 65–72 74 75 83 85 89–95 and 10 were non-RCTs (NRCTs),41 59 60 76 79 80 86–88 96 with most control groups receiving standardised care or being waiting list controls. Only three studies had included an active/attention control condition, for example, non-emotional writing or receiving an information booklet.70 71 74 One study offered gift certificates to the control group participants if they responded to the follow-up questionnaires.89 Relatively few studies were UCTs (k=8).62–64 73 77 81 82 84 The reporting of the participants’ medical treatment status was inconsistent. Five studies did not provide information on treatment status (whether or not in current ART treatment), 3 reported that some, but not how many, of the participants were in treatment, and 31 reported that their participants were currently in ART treatment, although not what kind of treatment, for example, IUI, IVF/ICSI or treatment cycle. The cause of infertility was also inconsistently reported, and some participants may still have been under evaluation during the study period. Twenty-five studies had included only women, while the remaining 14 had included both women and men. The included studies had reported data for a total of 3401 participants (3064 women and 347 men). The mean age and mean duration of infertility for intervention group participants were (32.7 years, ‘SD’ 2.2) and (4.6 years, ‘SD’ 2.1), and for control group participants (32.6 years, ‘SD’ 1.7) and (5.1 years, ‘SD’ 3.0), respectively. The specific intervention strategies mostly employed were cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT; k=8) and MBI (k=12). The remaining studies had used a variety of interventions, including stress management, hypnosis, art therapy, expressive writing intervention, crisis intervention and various types of counselling. Some studies had included more than one approach, for example, cognitive–behavioural approaches supplemented with mind–body techniques such as relaxation. To be categorised as MBI, a study had to use such strategies as the general approach over the course of intervention. Thus, if studies had mainly used CBT strategies and only incorporated other approaches, for example, relaxation exercises, in one or two sessions, they were categorised as CBT interventions. The number of sessions ranged from 1 to 24, lasting approximately from 20 min to 3 h, and the duration of psychosocial intervention ranged from 1 week to 28 months.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author | Country | Participants (N) I: intervention C: control assigned (final analysis) (men %) |

Study design | Intervention type* | Intervention category† | Intervention format | Number of sessions | Intervention duration (weeks) | Outcome: psychological‡ IS: infertility stress A: anxiety D: depression MF: marital function |

Outcome: pregnancy§ (+/−) | Quality score¶ J: Jadad 0–5 MJ: modified Jadad 0–12 J (MJ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O’Moore et al79 | Ireland, UK | I: 30 (22) (50%) C: 20 (20) (50%) |

NRCT | Autogenic training | MBI | Group | 8 | 8 | D: BDI A: STAI |

− | 1 (4) |

| Lukse62 | USA | I: 29 (29 (14)) | UCT | Counselling | Other | Group | 6 | 6 | D: DES | − | 0 (3) |

| Sarrel and DeCherney86 | USA | I: 20 (10) C: 20 (9) |

NRCT | Psychotherapeutic interview | Other | Couples | 1 | 1 | + | 0 (1) | |

| Domar et al63 | USA | I: 54 (54) | UCT | Mind/body programme | MBI | Group | 10 | 10 | A: STAI | − | 0 (3) |

| Domar et al64 | USA | I: 52 (41) | UCT | Behavioural medicine programme for infertility | MBI | Group | 10 | 10 | A: STAI | − | 1 (3) |

| Galletly et al82 | Australia | I: 37 (37) | UCT | Treatment programme | Other | Group | 24 | 24 | D: HADS A: HADS |

− | 1 (3) |

| McQueeney et al80 | USA | I: 20 (20) C: 9 (9) |

NRCT | Emotion-focused and problem-focused therapies | Other | Group | 6 | 6 | IS: ISD D: BDI |

− | 3 (7) |

| Tuschen-Caffier et al41 | Germany | I: 34 (22) C: 24 (24) |

NRCT | CBT | CBT | Couples | 10–12 | 32 | IS: one item MF: one item |

− | 1 (4) |

| Domar et al78 95 | USA | I: 56 (20) C: 63 (14) |

RCT | Psychological intervention | MBI | Group | 10 | 10 | D: BDI A: STAI |

+ | 4 (10) |

| Terzioglu91 | Turkey | I: 60 (60) (50%) C: 60 (60) (50%) |

RCT | Counselling | Other | Individual | 5 | 5 | D: BDI A: STAI |

+ | 2 (5) |

| Hosaka et al87 | Japan | I: 37 (37) C: 37 (37) |

NRCT | Structured intervention | MBI | Group | 5 | 5 | + | 3 (6) | |

| McNaughton-Cassill et al96 | USA | I: 43 (43)(39.5%) C: 37 (37)(48.6%) |

NRCT | Couples’ support | CBT | Couples | 6 | 3 | D: BDI A: BAI |

− | 2 (5) |

| Emery et al65 | Switzerland | I: 158 (110)(34.8%) C: 152 (131)(42.8%) |

RCT | Pre-IVF counselling | Other | Couples | 1 | 1 | D: BDI A: STAI |

− | 3 (6) |

| Lee66 | Taiwan | I: 64 (64) C: 68 (68) |

RCT | Nursing crisis intervention programme | MBI | Individual | 7 | 7 | D: SDS A: STAI |

− | 1 (4) |

| De Klerk et al92 | The Netherlands | I: 22 (18) C: 22 (15) |

RCT | Counselling | Other | Group | 3 | 4–5 | D: HADS A: HADS |

− | 3 (6) |

| Schmidt et al59 | Denmark | I: 13 (13) C: 435 (435) |

NRCT | Stress management | Other | Group | 5 | 6 | IS: COMPI | − | 1 (4) |

| Chan et al67 | Hong Kong, China | I: 101 (69) C: 126 (115) |

RCT | The Eastern body–mind intervention | MBI | Group | 4 | 4 | A: STAI | − | 3 (7) |

| Levitas et al88 | Israel | I: 89 (89) C: 96 (96) |

NRCT | Hypnosis | MBI | Individual | 1 | 1 | + | 0 (1) | |

| Nilforooshan et al58 | Iran | I: 30 (30)(50%) C: 30 (30)(50%) |

RCT | Cognitive–behavioural counselling | CBT | Group | 6 | 6 | D: BDI A: BAI |

− | 2 (6) |

| Tuil et al68 | The Netherlands | I: 108 (102) (50%) C: 96 (78) (48.7%) |

RCT | Internet-based health record | Other | Individual | Infinite | 2 | D: BDI A: STAI |

+ | 3 (6) |

| Cousineau et al83 | USA | I: 96 (49) C: 92 (49) |

RCT | Psycho-educational support | Other | Online | 1–2 | 4 | IS: FPI MF: RDAS |

− | 4 (8) |

| Faramarzi et al61 | Iran | I: 42 (29) C: 40 (30) |

RCT | CBT | CBT | Group | 10 | 10 | D: BDI A: Cattell |

− | 3 (6) |

| Lancastle and Boivin69 | Wales, UK | I: 28 (28) C: 27 (27) |

RCT | Brief coping intervention | Other | Individual | 14 | 2 | IS: CIQ | − | 4 (8) |

| Noorbala et al84 | Iran | I: 288 (288)(50%) | UCT | CBT | CBT | Group | 24 | D: BDI | − | 3 (8) | |

| Mori70 | Japan | I: 85 (85) C: 40 (40) |

RCT | Stress management | Other | Individual | 3 | 12 | D: HADS A: HADS |

− | 4 (8) |

| Panagopoulou et al71 | England, UK | I: 50 (50) C: 98 (98) |

RCT | Expressive writing intervention | Other | Individual | 3 | 1 | IS: ISS A: STAI |

+ | 3 (7) |

| Haemmerli et al72 | Switzerland | I: 60 (46) C: 64 (41) |

RCT | Coaching and support | Other | Online | 13 | 8 | IS: IDS D: CES-D A: STAI |

− | 3 (6) |

| Sexton et al85 | USA | I: 21 (15) C: 22 (16) |

RCT | Web-based coping with infertility | Other | Individual | 2 | IS: FPI | − | 3 (6) | |

| Domar et al89 | USA | I: 46 (46) C: 51 (51) |

RCT | Mind/body programme for infertility | MBI | Group | 10 | 10 | + | 4 (6) | |

| Hughes and de Silva73 | Canada | I: 21 (21) | UCT | Art therapy | Other | Group | 8 (2 h) | 8 | D: BDI A: BAI |

− | 0 (2) |

| Chan et al94 | Hong Kong, China | I: 141 (141) C: 110 (110) |

RCT | Integrative body–mind–spirit intervention | MBI | Group | 4 (3 h) | 4 | A: STAI MF: C-KMS |

+ | 3 (6) |

| Gorayeb et al90 | Brazil | I: 93 (93) C: 95 (95) |

RCT | Brief cognitive–behavioural intervention | CBT | Group | 5 (2 h) | 5 | + | 1 (4) | |

| Koszycki et al81 | Canada | I: 31 (23) | UCT | Interpersonal and supportive therapy | Other | Individual | 12 (50 min) | 12 | IS: FPI D: BDI HAM-D |

− | 3 (7) |

| Matthiesen et al74 | Denmark | I: 42 (15) C: 40 (16) |

RCT | Expressive writing intervention | Other | Individual | 3 (20 min) | 1 | IS: COMPI | − | 4 (8) |

| Mosalanejad et al75 76 | Iran | I: 32 (32) C: 33 (33) |

RCT | Cognitive–behavioural treatment | CBT | Group | 12 (2 h) | 12 | D: DASS A: DASS |

− | 1 (4) |

| Mosalanejad et al75 76 | Iran | I: 16 (16) C: 15 (15) |

NRCT | CBT | CBT | Group | 15 (1.5 h) | 16 | D: DASS A: DASS |

− | 2 (5) |

| Catoire et al77 | France | I: 50 (50) | UCT | Hypnosis | MBI | Individual | 4 | 1 | A: STAI | − | 4 (7) |

| Galhardo et al97 | Portugal | I: 55 (55) C: 37 (37) |

NRCT | Mindfulness-based programme for infertility | MBI | Group | 10 (2 h) | 10 | IS: ISE D: BDI A: STAI |

− | 1 (4) |

| Vizheh et al93 | Iran | I: 86 (86) (50%) C: 94 (86) (54.7%) |

RCT | Marital counselling | Other | Group | 3 (1.5hrs) | 3 | MF: MSQ | − | 4 (8) |

*Self-reported intervention type.

†Intervention type: CBT; MBI: mindfulness, yoga, relaxation, imagery, hypnosis, etc; Other: all other intervention types, for example, counselling, psychoeducation, supportive therapy, expressive writing intervention, brief therapy, emotion and problem focused therapy, and narrative therapy.

‡Outcome measures: Infertility stress: CIQ, the Coping with Infertility Questionnaire; COMPI, the Copenhagen Multi-centre Psychosocial Infertility problem stress scale; FPI, Fertility Problem Index; IDS, Infertility Distress Scale; ISD, Infertility-Specific Distress and Well-being; ISE, Infertility Self-efficacy Scale; ISS, the Infertility and Strain Scale—Depression: BDI, the Beck Depression Inventory; CES-D, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression—short version; DES, The Differential Emotion Scale; DASS, the Depression and Anxiety Stress Scale—depression; HADS, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; SDS, Zung's Self-administered Depression Scale—Anxiety: BAI, the Beck Anxiety Inventory; Cattell, Cattell Anxiety Inventory; DASS, the Depression and Anxiety Stress Scale—anxiety; HAM-D, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale—subscale anxiety; STAI, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory—Marital function: C-KMS, Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale—Chinese version RDAS (Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale)—dyadic cohesion subscale; MSQ, Marital Satisfaction Questionnaire.

§Pregnancy is defined as a clinical pregnancy when the heartbeat of the fetal sac is evident in the uterus with an ultrasound scan.

¶Jadad range 0–5 an assessment tool rating the quality and methodology of the studies included37 and the modified Jadad range 0–11(total score) included additional points for: inclusion of a control group, pre–post data, blinding of participants or researchers, use of standardised and reliable outcome measures and report of pre–post correlations.

CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; IVF, in vitro fertilisation; MBI, mind/body intervention; NRCT, non-randomised controlled trial; RCT, randomised controlled trial; UCT, uncontrolled trial (pre–post).

Attrition

A total of 15 studies reported the number of participants at baseline and then again at follow-up, and as seen in table 1, the number of dropouts varied across studies. Although the dropout rates in the intervention groups were somewhat higher (mean 30.5% (SD 20.2)) than in controls (24.9% (24.8)), the difference did not reach statistical significance (t(28) 0.68, p=0.50). Furthermore, only four studies explicitly stated that the analysis was based on an intention-to-treat (ITT) approach.70 72 83 92 Two additional studies used methods comparable to ITT, for example, carrying last (baseline) observations forward or use of multilevel linear modelling.69 97 Four studies stated that there were no differences between completers and dropouts without specifying this further,41 64 81 85 and the remaining studies failed to report whether there were dropouts or how such missing data were dealt with. The possible association between ES and uneven dropouts in the intervention and control groups was analysed for the 15 studies that reported dropouts by regressing the difference in dropout rates on the overall ES across all outcomes. The result indicated that larger dropouts in the intervention group compared were generally associated with smaller ES (Slope=−0.02), but the association did not reach statistical significance (p=0.268).

Quality ratings

All included studies were methodologically assessed with the original Jadad scale and the additional methodological criteria. The original Jadad scores ranged from 0 to 4 with a mean of 2.28 (SD 1.36), and the modified total quality scores ranged from 1 to 10 with a mean of 5.36 (SD 2.05). The main methodological issue was that only very few studies attempted to blind or mask the intervention conditions to either patients or researchers. The quality ratings for each criterion for each study and total scores are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Modified Jadad scores (original Jadad criteria +6 additional criteria)

|

Jadad criteria |

Additional criteria |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | a | b | c | d | e | f | Jadad | Total |

| Randomised | Double blind | Withdrawals and dropouts | Randomisation (evaluation) | Blinding (evaluation) | Randomisation (evaluation) | Blinding (evaluation) | Control group | Preassessment and postassessment | Blinding (patients) | Blinding (researchers) | Standardised and reliable outcome | Pre–post correlation | Jadad scores | Total scores | |

| O’Moore et al79 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Lukse62 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Sarrel and DeCherney86 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Domar et al63 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Domar et al64 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Galletly et al82 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| McQueeney et al80 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| Tuschen-Caffier et al41 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Domar et al78 95 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 10 |

| Terzioglu91 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Hosaka et al87 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| McNaughton-Casill et al96* | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Emery et al65 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Lee66 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| De Klerk et al92 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Schmidt et al59 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Chan et al67 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Levitas et al88 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Nilforooshan et al58 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Tuil et al68 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Cousineau et al83 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 8 |

| Faramarzi et al61 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Lancastle and Boivin69 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 8 |

| Noorbala et al84* | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Mori70 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 8 |

| Panagopoulou et al71 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| Haemmerli et al72 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Sexton et al85 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Domar et al89 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| Hughes and de Silva73 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Chan et al94 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Gorayeb et al90 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Koszycki et al81 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| Matthiesen et al74 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 8 |

| Mosalanejad et al75 76 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Mosalanejad et al75 76 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Catoire et al77* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Galhardo et al97 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Vizheh et al93 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 8 |

Criteria 1–7 in bold font are the original Jadad scores, a–f are the additional criteria. (1) Was the study described as randomised; (2) Was the study described as double blind; (3) Was there a description of withdrawals and dropouts; (4) The method of randomisation was described, and appropriate; (5) The method of blinding was described, and appropriate; (6) The method of randomisation was described, but inappropriate; (7) The method of blinding was described, but inappropriate; (a) The study included a control group; (b) The study included preassessment and postassessment; (c) There was an attempt of blinding or masking the active condition to patients; (d) There was an attempt of blinding the researchers; (e) The study used standardised and reliable outcome measures and (f) The study reported pre–post correlation.

*In these studies, the original Jadad score and the modified quality score relate to the methodological quality of the published study. For the purpose of the meta-analyses, some of the groups were collapsed or omitted, for example, if they compared two or more interventions or compared a psychological intervention with a medical treatment, thereby changing design status as shown in table 1.

Effects of psychosocial intervention

The results of the meta-analyses are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Results of meta-analyses of effects of psychosocial intervention on psychological outcomes and pregnancy rates among infertile couples

| Sample size | Heterogeneity* |

Global ES |

Fail-safe numbers‡ | Criterion§ | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | N | Q | df | p Value | I2 | Hedges g† | 95% CI | p Value | |||

| Main effects | |||||||||||

| Pregnancy | |||||||||||

| Pregnancy, women | 10 | 1324 | 22.0 | 9 | 0.009 | 59.0 | 2.01 (RR) | 1.48 to 2.73 | <0.001 | 130 | 60 |

| Adjusted for publication bias | (13) | – | – | – | – | – | 1.57 (RR) | 1.10 to 2.25 | <0.05 | – | – |

| Psych. combined, women+men | 35 | 2746 | 259.2 | 34 | <0.001 | 86.9 | 0.59 | 0.38 to 0.80 | <0.001 | 1552 | 185 |

| Adjusted for publication bias | (42)¶ | – | – | – | – | – | 0.31 | 0.07 to 0.56 | <0.05 | – | – |

| Psych. combined, women | 28 | 2076 | 130.8 | 27 | <0.001 | 76.4 | 0.51 | 0.32 to 0.70 | <0.001 | 798 | 150 |

| Adjusted for publication bias | (34)¶ | – | – | – | – | – | 0.30 | 0.09 to 0.51 | <0.05 | – | – |

| Psych. combined, men | 7 | 347 | 8.9 | 6 | 0.178 | 32.8 | 0.34 | 0.08 to 0.59 | 0.010 | 12 | 45 |

| Between-group** (women vs men) | 35 | 2110 | 1.2 | 1 | NS | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Infertility distress | |||||||||||

| Infertility distress, women+men | 10 | 615 | 21.4 | 9 | 0.01 | 58.0 | 0.24 | −0.02 to 0.50 | NS | – | – |

| Infertility distress, women | 6 | 371 | 17.8 | 5 | 0.003 | 71.8 | 0.37 | −0.06 to 0.79 | NS | – | – |

| Depressive symptoms | |||||||||||

| Depression symptom, women+men | 21 | 1558 | 367.5 | 20 | <0.001 | 94.6 | 1.00 | 0.54 to 1.45 | <0.001 | 1022 | 115 |

| Adjusted for publication bias | (25)¶ | – | – | – | – | – | 0.31 | −0.20 to 0.84 | NS | − | − |

| Depressive symptom, women | 17 | 992 | 107.7 | 16 | <0.001 | 85.1 | 0.73 | 0.41 to 1.06 | <0.001 | 393 | 95 |

| Adjusted for publication bias | (23)¶ | − | − | − | − | − | 0.29 | −0.07 to 0.65 | NS | − | − |

| Depressive symptom, men | 5 | 243 | 1.9 | 4 | 0.749 | 0.00 | 0.13 | −0.11 to 0.37 | NS | − | − |

| Between-group** (women vs men) | 22 | 1235 | 8.5 | 1 | <0.004 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Anxiety | |||||||||||

| Anxiety, women+men | 25 | 2159 | 144.4 | 24 | <0.001 | 83.4 | 0.51 | 0.31 to 0.71 | <0.001 | 760 | 135 |

| Adjusted for publication bias | (29)¶ | − | − | − | − | − | 0.31 | 0.07 to 0.54 | <0.05 | − | − |

| Anxiety, women | 23 | 1737 | 114.3 | 22 | <0.001 | 80.8 | 0.53 | 0.32 to 0.73 | <0.001 | 631 | 125 |

| Adjusted for publication bias | (27)¶ | − | − | − | − | − | 0.32 | 0.08 to 0.57 | <0.05 | − | − |

| Anxiety, men | 5 | 246 | 8.7 | 4 | 0.070 | 53.8 | 0.32 | −0.04 to 0.67 | NS | − | − |

| Between-group** (women vs men) | 28 | 1983 | 1.0 | 1 | NS | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Marital function | |||||||||||

| Marital function, women+men | 5 | 633 | 14.6 | 4 | 0.006 | 72.6 | 0.09 | −0.23 to 0.41 | NS | − | − |

| Marital function, women | 4 | 587 | 14.5 | 3 | 0.002 | 79.3 | 0.08 | −0.30 to 0.46 | NS | − | − |

| Moderator analyses | |||||||||||

| Pregnancy (women) | |||||||||||

| Study design†† | |||||||||||

| RCT | 6 | 856 | 10.8 | 5 | 0.057 | 53.5 | 1.67 (RR) | 1.17 to 2.40 | <0.05 | 22 | 40 |

| NRCT | 4 | 468 | 7.9 | 3 | 0.048 | 62.1 | 2.80 (RR) | 1.55 to 5.06 | <0.001 | 31 | 30 |

| Adjusted for publication bias | (6)¶ | − | − | − | − | − | 1.93 (RR) | 1.07 to 3.49 | <0.05 | − | − |

| Between-group** | 10 | 1324 | 2.1 | 1 | NS | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Intervention format | |||||||||||

| Group | 5 | 691 | 10.9 | 4 | 0.027 | 63.4 | 2.03 (RR) | 1.29 to 3.20 | <0.01 | 28 | 35 |

| Individual | 4 | 433 | 2.2 | 3 | 0.531 | 0.0 | 1.65 (RR) | 1.26 to 2.17 | <0.001 | 8 | 30 |

| Between-group** | 9 | 1124 | 0.5 | 1 | NS | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Psychological outcomes combined (women+men) | |||||||||||

| Study design†† | |||||||||||

| RCT | 20 | 2185 | 232.4 | 19 | <0.001 | 91.8 | 0.70 | 0.36 to 1.03 | <0.001 | 642 | 110 |

| Adjusted for publication bias | (24)¶ | − | − | − | − | − | 0.26 | −0.10 to 0.68 | NS | − | − |

| NRCT | 8 | 450 | 14.9 | 7 | 0.037 | 53.1 | 0.28 | −0.00 to 0.57 | NS | − | − |

| UCT | 7 | 215 | 6.0 | 6 | 0.424 | 0.0 | 0.55 | 0.40 to 0.70 | <0.001 | 90 | 45 |

| Adjusted for publication bias | (10)¶ | − | − | − | − | − | 0.51 | 0.36 to 0.66 | <0.05 | − | − |

| Between-group** | 35 | 2850 | 3.9 | 2 | NS | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Intervention types | |||||||||||

| CBT | 7 | 475 | 39.0 | 6 | <0.001 | 84.6 | 0.84 | 0.33 to 1.35 | 0.001 | 107 | 45 |

| Adjusted for publication bias | (10)¶ | − | − | − | − | − | 0.37 | −0.19 to 0.93 | NS | − | − |

| MBI | 9 | 841 | 57.7 | 8 | <0.001 | 86.1 | 0.61 | 0.17 to 0.65 | <0.001 | 158 | 55 |

| Adjusted for publication bias | (10)¶ | − | − | − | − | − | 0.42 | 0.01 to 0.84 | <0.05 | − | − |

| Other | 19 | 1430 | 149.2 | 9 | <0.001 | 87.9 | 0.50 | 0.18 to 0.81 | 0.002 | 246 | 105 |

| Adjusted for publication bias | (24)¶ | − | − | − | − | − | 0.17 | −0.20 to 0.54 | NS | − | − |

| Between-group** | 35 | 2746 | 1.3 | 2 | NS | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Intervention format | |||||||||||

| Group | 20 | 1484 | 87.2 | 19 | <0.001 | 78.2 | 0.76 | 0.55 to 0.98 | <0.001 | 959 | 110 |

| Adjusted for publication bias | (26)¶ | − | − | − | − | − | 0.50 | 0.25 to 0.75 | <0.05 | − | − |

| Individual | 9 | 834 | 17.7 | 8 | 0.023 | 54.9 | 0.13 | −0.08 to 0.35 | NS | − | − |

| Couples | 3 | 284 | 92.3 | 2 | <0.001 | 97.8 | 1.07 | −1.02 to 3.16 | NS | − | − |

| Online | 3 | 248 | 1.2 | 2 | 0.541 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.22 to 0.28 | NS | − | − |

| Between-group** | 35 | 2850 | 24.5 | 3 | <0.001 | − | − | − | − | − | |

*Q statistic: p values<0.1 taken to suggest heterogeneity. I2 statistic: 0% (no heterogeneity), 25% (low heterogeneity), 50% (moderate heterogeneity) and 75% (high heterogeneity).

†ESR=Hedges g. Standardised mean difference, adjusting for small sample bias. A positive value indicates an ES in the hypothesised direction, that is, reduced pain or relatively smaller increase in pain in the intervention group. All ES were combined using a random effects model. To ensure independency, if a study reported results for more than one pain measure, the ES were combined (mean), ensuring that only one ES per study was used in the calculation.

‡Fail-safe number=number of non-significant studies that would bring the p value to non-significant (p>0.05).

§A fail-safe number exceeding the criterion (5×k+10) indicates a robust result.98

¶If analyses indicated the possibility of publication bias, missing studies were imputed and an adjusted ESR was calculated (italics); (K) indicates the number of published studies+number of imputed studies.

**Meta-ANOVA (between-study comparisons).

††RCT, NRCT and UCT.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; ES, effect size; MBI, mind/body intervention; NRCT, non-randomised controlled trial; NS, not significant; Psych, psychological outcomes; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RR, risk ratio; UCT, uncontrolled trial (pre–post).

Pregnancy rates

A statistically significant and robust ES (RR=2.01) was found for the 10 studies which had investigated effects of psychosocial intervention on clinical pregnancy rates, with the chance of becoming pregnant being doubled in the intervention group. Adjusting for possible publication bias, the RR was somewhat lower (1.57). A forest plot of the effects of psychological intervention on pregnancy outcomes is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Effects of psychosocial intervention on pregnancy rates.

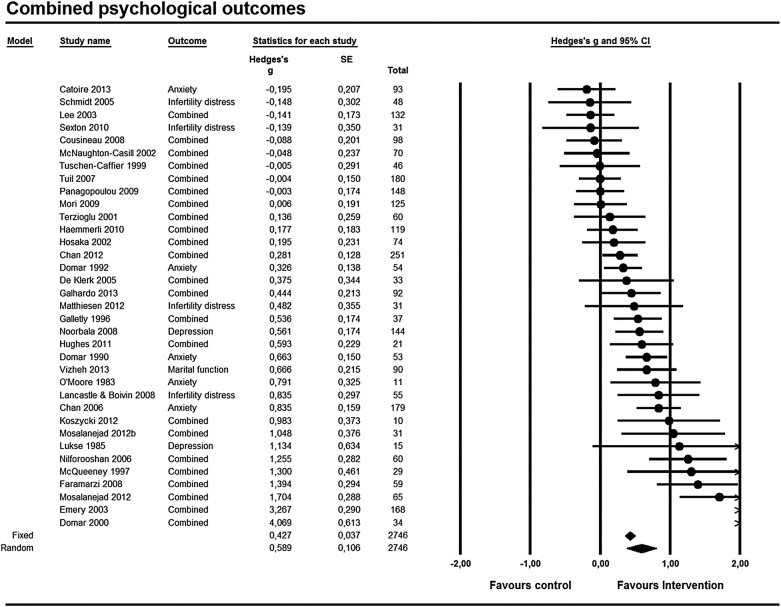

Combined psychological outcomes

Combining the ES of the 35 studies which had included one or more psychological outcomes revealed a statistically significant, robust,51 medium39 ES (g=0.59). The results indicated possible publication bias (skewed funnel plot, Egger's test (p<0.05)) in favour of larger published ES. When imputing missing ES,52 the resulting adjusted pooled ES was smaller (0.31) but remained statistically significant. Taking gender into consideration, the ES (0.51) remained statistically significant for women, still suggesting a robust effect. The ES was smaller for men (0.34) and did not reach statistical significance. A forest plot of the effects of psychological intervention on the combined psychological outcomes is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Effects of psychosocial intervention on combined psychological outcomes.

Infertility-related distress

Only 10 studies had included infertility-related distress as an outcome. Small ES were found for women and men combined (0.24) and women alone (0.37) and did not reach statistical significance.

Depression

Twenty-one studies had assessed depressive symptoms. A statistically significant ES (1.00) was found for women and men combined. However, when adjusting for possible publication bias, the results changed dramatically to a small, non-significant ES of 0.31. Similar results were found for women alone with a statistically significant ES of 0.73, which was reduced to a non-significant 0.29 after adjusting for possible publication bias. For men alone, the ES (0.13) did not reach statistical significance.

State anxiety

Twenty-five studies had included state anxiety as an outcome. A statistically significant, robust medium ES (0.51) was found for women and men combined. Adjusting for possible publication bias led to a smaller but statistically significant ES (0.31). For women, the ES of 0.53 was statistically significant, but smaller (0.32) and non-significant when adjusting for publication bias. For men only, the analysis produced a small, non-significant ES of 0.32.

Marital function

Only five studies (N=633) had included measures of marital function, but only very small (ES 0.09–0.08), non-significant effects were found.

Possible moderators

As the Q statistics were generally statistically significant (p<0.10) and the I2 statistic indicated low-to-medium heterogeneity, when a sufficient number of studies were available for each analysis, we explored possible sources of heterogeneity and analysed whether the ES for pregnancy and combined psychological outcomes varied according to between-study differences in study design and intervention characteristics (type and format). The results are shown in table 3.

Study design

The ES found for pregnancy outcomes were statistically significant for RCTs (RR=1.7) and NRCTs (2.8), with the ES for NRCTs being considerably smaller (1.9) when adjusting for publication bias. The difference did not reach statistical significance. For psychological outcomes, statistically significant results were found for RCTs (g=0.70) and UCTs (0.55), but not for NRCTs (0.28). When adjusting for publication bias, the ES for RCTs was considerably reduced (0.26). Furthermore, between-group differences did not reach statistical significance.

Intervention type

The number of studies for each intervention type was insufficient to explore differences in pregnancy outcomes. For the combined psychological outcomes, statistically significant and, as indicated by the large fail-safe numbers, robust effects were found for all three intervention categories with the largest ES found for CBT (g=0.84), followed by MBI (0.61) and other intervention types (0.50). The between-group differences, did not reach statistical significance. Furthermore, the results suggested the possibility of publication bias, and when adjusting for publication bias, all three ES were reduced from medium to small.

Intervention format

For pregnancy outcomes, the number of studies was sufficient for group and individual formats. Both formats yielded statistically significant ES (RR 2.03 and 1.65), and the between-group difference did not reach statistical significance. For the combined psychological outcomes, a statistically significant effect was found for the Group format (g=0.76; p<0.001). The ES for intervention formats such as individual, couples and online did not reach statistical significance. The overall between-group difference for intervention formats was statistically significant (p<0.001).

Other study characteristics

The possible moderating influence of the continuously assessed study characteristics of mean age, intervention duration, number or sessions, and study quality (modified quality scores) were analysed with meta-regression. As seen in table 4, no significant effects were found for any of the moderators for either pregnancy or the combined psychological outcomes. A total of six studies had examined the effects on pregnancy and anxiety. When examining the possible role of anxiety reduction as a mediator of the effect on pregnancy outcome with meta-regression, a statistically significant association was found between the ES for anxiety and pregnancy, indicating that the greater the reduction in anxiety, the greater the likelihood of achieving pregnancy (see table 4).

Table 4.

Results of meta-regression analyses

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | K | β* | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy | ES—anxiety | 6 | 0.19 | 0.06 to 0.31 | 0.004 |

| Mean age | 9 | −0.05 | −0.19 to 0.10 | 0.534 | |

| Intervention duration | 9 | 0.01 | −0.03 to 0.06 | 0.669 | |

| Number of sessions | 9 | −0.00 | −0.08 to 1.07 | 0.922 | |

| Study quality (quality scores)† | 10 | −0.02 | −0.09 to 0.04 | 0.477 | |

| Psych. combined | Mean age | 32 | −0.05 | −0.12 to −0.02 | 0.214 |

| Intervention duration | 32 | 0.01 | −0.02 to 0.04 | 0.518 | |

| Number of sessions | 27 | 0.03 | −0.01 to 0.07 | 0.150 | |

| Study quality (quality scores)†‡ | 35 | −0.02 | −0.06 to 0.02 | 0.415 |

*Mixed effects regression: unrestricted maximum likelihood.

†Modified Jadad quality score.

‡p Values for individual psychological outcomes; 0.09 (anxiety)–0.58 (depression).

Bold typeface indicates a significant result. ES, effect size; Psych, psychological outcomes.

Discussion

Primary findings

Our meta-analysis of the available evidence suggests that women who receive some form of psychological intervention are approximately twice as likely to become pregnant when compared with controls receiving standardised care or active control intervention. Although the results of the 10 currently available studies taken together appeared robust, there were some indications of publication bias in favour of studies with larger positive ES. It should also be noted that the precision of the ES estimate is limited, with possible RRs ranging from approximately 1.5 to 2.7. Furthermore, although the between-group difference did not reach statistical significance when disregarding the possibility of publication bias, NRCTs yielded greater effects (RR 2.8 (95% CI 1.55 to 5.06)) than RCTs (RR 1.7 (95% CI 1.17 to 2.40)). Compared with other types of interventions that historically have been introduced to improve pregnancy rates in ART (improved culture media, new hormone stimulation regimens, etc), even an effect corresponding to the lower limit of the CI is substantial. While the results could be considered surprising, the available data do not provide any clear-cut reasons to reject this finding, which is further supported by the results of the meta-regression showing that larger reductions in anxiety were associated with improved pregnancy outcomes. With respect to the psychological outcomes currently reported in the literature, the results suggest that psychological intervention could be effective in reducing anxiety (25 studies) as well as depressive symptoms (21 studies) with the effects corresponding to medium and large ES (0.5 and 1.0). As seen for pregnancy outcomes, there were indications of publication bias in the direction of larger positive effects, and adjusting for publication bias resulted in a considerably smaller, statistically non-significant, ES for depressive symptoms. The pooled results did not reach statistical significance for the 10 studies which had investigated effects on infertility-related distress and the 5 studies which had included measures of marital function.

Comparing with results of previous reviews

The present review included 39 studies with a total of 3401 women (3064) and men (347). The participants received various psychosocial interventions lasting from 1 week to 6 months, including CBT, emotional disclosure, psychoeducation and MBIs. The present review evaluates almost twice the number of studies included in the most recent previous review,31 which reported mixed results of the efficacy of psychosocial intervention. Whereas the former review found no evidence for attenuating distress, there was promising support of psychological intervention increasing pregnancy chances for women not receiving ART.31 In line with the second review from 2005,30 we found more credible results for group intervention than for other formats, for example, online, individual and couples interventions.30 The first review published in 2003 also highlighted group interventions as more effective, especially if the interventions emphasised education and skills training, such as relaxation. Our results concurred with these earlier observations, suggesting that interventions delivered in groups may be more effective in reducing distress. Moreover, although the comparison did not reach statistical significance, prior to adjusting for publication bias, the intervention type of CBT appeared to be more effective than MBI and other types of interventions. It should be noted that the categorisation of interventions may be somewhat ambiguous. For example, the study by Cousineau et al83 could have been categorised as an MBI, as the authors had provided a website that directed attention towards relaxation exercises. However, as there was no reporting of whether the participants were engaged in weekly or daily training, we chose to interpret relaxation as an optional feature, and hence the study was not categorised as an MBI. The possible ambiguity and considerable variability in interventions forced us to categorise many studies as ‘other’, which limits our understanding of the possible mechanisms in psychosocial interventions. Taken together, the available data do not provide a clear basis for understanding the possible differences between effects of different intervention types, and the results should be interpreted with caution. The more recently conducted studies included in the present review have contributed by increasing the size of the available data set considerably, and taken together, the currently available evidence suggests that offering psychosocial interventions may improve both the chances of pregnancy and the quality of life for infertile patients going through fertility treatment.

Strengths and limitations

Our systematic review and meta-analysis has several strengths. We conducted a comprehensive search and performed the review in accordance with the recommended guidelines.34 In order to limit the possibility of selection bias, we encouraged authors of eligible studies to elaborate on their results if the data reported were insufficient, and asked authors of papers written in a foreign language to submit their results to us in English. The included studies represented a range of different countries, have used comparable outcome measures, and provided fairly comprehensive descriptions of the interventions studied. In addition, we conducted a detailed evaluation of the methodological quality in order to detect any issues that could possible affect the accuracy of the ES calculated. While not all characteristics, in particular reproductive, could be assessed; most general methodological aspects were covered. We also explored heterogeneity and made adjustments for possible publication bias, when required.

Some limitations of the currently available data should also be noted. First, the samples investigated may not have been as homogeneous as could be wished for. A small number of infertile participants did not receive treatment with ART, and furthermore, it was not consistently reported what type of ART procedure the participants received, what phase or treatment they were in, or the causes of infertility. This information is clearly important when interpreting the outcomes, and unknown between-study and within-study between-group differences, for example, in numbers of cycles, idiopathic infertility and embryo transfer, may have influenced the results, in particular for pregnancy outcomes. However, such differences are likely to be less important in RCTs, where randomisation is expected to reduce their influence. Although the difference did not reach statistical significance, RCTs reported smaller ES for pregnancy outcomes than NRCTs, which could be interpreted as supporting the concern that infertility and treatment characteristics may have been unevenly distributed between psychological treatment arms, thus increasing the risk for misattribution of outcomes to intervention, at least for NRCTs. On the other hand, we found no statistical significant associations between study quality scores and either pregnancy or psychological outcomes, no statistically significant differences in dropout rates between intervention and control groups, and, as suggested by the large fail-safe numbers, the improvements generally appeared quite robust. A second possible limitation is the high level of heterogeneity indicated by the Q and I2 statistics, and the pooled ES reported in the present review should thus be viewed as an estimate of the average expected effect across a wide range of different settings. A third issue is that the considerable dropout rates and lack of ITT analyses may have influenced the results, and it cannot be excluded that fertility-related and treatment-related factors such as non-optimal fertilisation, small number of eggs, etc, may have demotivated some participants and made them dropout of the study, while individuals who progressed through the treatment phases with more satisfactory outcomes were more likely to complete the study. Fourth, the indications of publication bias found for several results suggest the possibility of a ‘file drawer problem’, that is, the existence of relevant unpublished null findings, a common problem when conducting systematic reviews. Finally, owing to inconsistencies in the reporting of causes of infertility, we are unable to evaluate the possible associations between ES and causes of infertility. Although meta-analysis remains the gold standard when evaluating the current evidence within a field of research, as is often the case with systematic reviews, qualitative as well as quantitative, the overall level of the evidence reported in our review may be challenged by publication bias and the heterogeneity and methodological limitations of the available published studies.

Clinical and practical implications

We found evidence for improvement in general psychological symptoms such as anxiety and depression, but not for infertility-specific distress. A possible explanation for the latter could be the lack of sensitivity of the infertility-related distress measures used. The questions used in these measures are directly concerned with thoughts and feelings about involuntary childlessness, and rumination about the involuntary childlessness may persist even when psychosocial intervention improves general psychological well-being. Of particular interest is the result of our meta-regression analysis of the six studies which had included both pregnancy and anxiety as outcomes showing that larger reductions in anxiety were associated with greater chances of pregnancy. Anxiety is a state of arousal, which over time is physically and mentally stressful for the individual.17 Reducing distress, anxiety in particular, may increase the physiological ability to cope with stress and advance the possibility of impregnation. We found no association between mean age and pregnancy rates outcomes, which may seem surprising, since age is the most important predictor of pregnancy outcomes of ART.99 100 However, our meta-regression was conducted for the mean age of the samples, and the mean age across study samples showed little variation (mean age 32.7; SD 2.4). The rather narrow age interval across study samples may explain an apparent lack of association between age and chance of pregnancy. Our findings also suggest that group interventions appear to be more efficacious than individual, couples or online interventions. There could be various reasons for this. First, group interventions had a longer duration (mean 9.5 weeks) and involved more sessions (8.3) than individual interventions (mean 5.3 and 4.4), and second, there is evidence of a positive impact of ‘group settings’, that is, the sense of community between participants, reducing the feelings of isolation or alienation and sharing with individuals in the same life situation, etc.101–104

Recommendations for future research

Despite the overall positive effects of psychosocial interventions found in the literature, our results suggest a need for further studies with more rigorous methodology, including more strict reporting of causes of infertility, the types of ART used, and which phases of treatment the participants are in. Also, most of the studies were conducted in high-income countries; it is therefore important to note that the assertions made here cannot be generalised to low-income and developing countries. There is thus a need for research in low-income or developing countries as well. Another aspect pertaining to generalisability is the challenge of comparing volunteering infertile participants in psychosocial efficacy studies with the general population of infertile individuals. The response rates in this area are moderate, and it seems important in future studies to explore and compare characteristics of dropouts and completers, as well as of non-responders and responders. Furthermore, it would be of importance to develop clinically meaningful categories of distress with the purpose of improving interventions targeted to the various types and levels of distress experienced by the participants. Psychological well-being/distress fluctuates over time during fertility treatment and a stepped care approach could be potentially valuable in this population.105 It is also possible that interventions aimed at relieving distress conducted at different phases in treatment may obtain different psychological outcome results. This calls for improved reporting and comparability of the timing of psychosocial interventions and greater precision and comparability of the timing of outcome assessments. Also needed are studies testing specific hypotheses concerning possible moderating and mediating mechanisms of the effects of interventions on distress and pregnancy outcomes. For example, which psychosocial factors do we need to target to optimise effects on distress and pregnancy rates, and which biomarkers affected by psychosocial interventions, for example, oxidative stress, inflammatory processes, can best explain the observed effects? This could assist in developing a more solid evidence base providing better guidance for patients, health professionals and policymakers about ‘what works for whom’ in infertile patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis of 39 studies suggests that psychosocial interventions, in particular CBT and MBI interventions, are beneficial for reducing distress and for improving pregnancy outcomes of ART. Moreover, there is some preliminary evidence to suggest that reduction in anxiety achieved through psychological intervention may improve the chance of pregnancy. Despite the robust overall effect found, the considerable heterogeneity of the available studies with respect to methodological quality, intervention type and format still warrants caution as to the conclusions which can be drawn.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Gina Bay, Librarian at the Library, Department of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, School of Business and Social Sciences, Aarhus University for valuable and tireless assistance throughout the database search process. They would also like to give their most grateful thanks to the researchers who provided them with additional data on their studies or aided them in other ways.

Footnotes

Contributors: RZ and YF designed the protocol. YF developed search strategies and IF-V, NGS and YF performed the searches and study selection. YF and IF-V undertook data extraction and quality assessments. RZ was responsible for analysing the data. YF drafted the manuscript and IF-V, NGS, HJI and RZ contributed to the manuscript throughout the process. All authors provided inputs and were involved with the interpretation of this review. YF is the study guarantor.

Funding: YF was supported by a research grant from The Danish Agency for Science Technology and Innovation.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.kv50v.

References

- 1.Hart VA. Infertility and the role of psychotherapy. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2002;23:31–41. 10.1080/01612840252825464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oddens BJ, den Tonkelaar I, Nieuwenhuyse H. Psychosocial experiences in women facing fertility problems—a comparative survey. Hum Reprod 1999;14:255–61. 10.1093/humrep/14.1.255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cwikel J, Gidron Y, Sheiner E. Psychological interactions with infertility among women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2004;117:126–31. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swan SH, Elkin EP, Fenster L. The question of declining sperm density revisited: an analysis of 101 studies published 1934–1996. Environ Health Perspect 2000;108:961–6. 10.1289/ehp.00108961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skakkebaek NE, Jorgensen N, Main KM et al. . Is human fecundity declining? Int J Androl 2006;29:2–11. 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00573.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2005;1:293–319. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benyamini Y, Gozlan M, Kokia E. Variability in the difficulties experienced by women undergoing infertility treatments. Fertil Steril 2005;83:275–83. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alesi R. Infertility and its treatment—an emotional roller coaster. Aust Fam Physician 2005;34:135–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merari D, Chetrit A, Modan B. Emotional reactions and attitudes prior to in vitro fertilization: an inter-spouse study. Psychol Health 2002;17:629–40. 10.1080/08870440290025821 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klonoff-Cohen H, Chu E, Natarajan L et al. . A prospective study of stress among women undergoing in vitro fertilization or gamete intrafallopian transfer. Fertil Steril 2001;76:675–87. 10.1016/S0015-0282(01)02008-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edelmann RJ, Connolly KJ, Bartlett H. Coping strategies and psychological adjustment of couples presenting for IVF. J Psychosom Res 1994;38:355–64. 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90040-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eugster A, Vingerhoets AJ. Psychological aspects of in vitro fertilization: a review. Soc Sci Med 1999;48:575–89. 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00386-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanton AL, Dunkel-Schetter C, eds. Infertility: perspectives from stress and coping research. In: Psychological adjustment to infertility: an overview of conceptual approaches. The Plenum series on stress and coping New York, NY, USA: Plenum Press, 1991:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benyamini Y, Gozlan M, Kokia E. Women's and men's perceptions of infertility and their associations with psychological adjustment: a dyadic approach. Br J Health Psychol 2009;14:1–16. 10.1348/135910708X279288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.du Plessis SS, Makker K, Desai NR et al. . Impact of oxidative stress on IVF. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol 2008;3:539–54. 10.1586/17474108.3.4.539 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agarwal A, Allamaneni SS. Role of free radicals in female reproductive diseases and assisted reproduction. Reprod Biomed Online 2004;9:338–47. 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)62151-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tracey KJ. The inflammatory reflex. Nature 2002;420:853–9. 10.1038/nature01321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, McGuire L, Robles TF et al. . Emotions, morbidity, and mortality: new perspectives from psychoneuroimmunology. Annu Rev Psychol 2002;53:83–107. 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Csemiczky G, Landgren BM, Collins A. The influence of stress and state anxiety on the outcome of IVF-treatment: psychological and endocrinological assessment of Swedish women entering IVF-treatment. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2000;79:113–18. 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2000.079002113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stoleru S, Teglas JP, Fermanian J et al. . Psychological factors in the aetiology of infertility: a prospective cohort study. Hum Reprod 1993;8:1039–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demyttenaere K, Nijs P, Evers-Kiebooms G et al. . Coping and the ineffectiveness of coping influence the outcome of in vitro fertilization through stress responses. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1992;17:655–65. 10.1016/0306-4530(92)90024-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanders KA, Bruce NW. Psychosocial stress and treatment outcome following assisted reproductive technology. Hum Reprod 1999;14:1656–62. 10.1093/humrep/14.6.1656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smeenk JM, Verhaak CM, Vingerhoets AJ et al. . Stress and outcome success in IVF: the role of self-reports and endocrine variables. Hum Reprod 2005;20:991–6. 10.1093/humrep/deh739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ebbesen SM, Zachariae R, Mehlsen MY et al. . Stressful life events are associated with a poor in-vitro fertilization (IVF) outcome: a prospective study. Hum Reprod 2009;24:2173–82. 10.1093/humrep/dep185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klonoff-Cohen H. Female and male lifestyle habits and IVF: what is known and unknown. Hum Reprod Update 2005;11:179–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Homan GF, Davies M, Norman R. The impact of lifestyle factors on reproductive performance in the general population and those undergoing infertility treatment: a review. Hum Reprod Update 2007;13:209–23. 10.1093/humupd/dml056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matthiesen SM, Frederiksen Y, Ingerslev HJ et al. . Stress, distress and outcome of assisted reproductive technology (ART): a meta-analysis. Hum Reprod 2011;26:2763–76. 10.1093/humrep/der246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boivin J, Griffiths E, Venetis CA. Emotional distress in infertile women and failure of assisted reproductive technologies: meta-analysis of prospective psychosocial studies. BMJ 2011;342:d223 10.1136/bmj.d223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boivin J. A review of psychosocial interventions in infertility. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:2325–41. 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00138-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Liz TM, Strauss B. Differential efficacy of group and individual/couple psychotherapy with infertile patients. Hum Reprod 2005;20:1324–32. 10.1093/humrep/deh743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haemmerli K, Znoj H, Barth J. The efficacy of psychological interventions for infertile patients: a meta-analysis examining mental health and pregnancy rate. Hum Reprod Update 2009;15:279–95. 10.1093/humupd/dmp002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I et al. . Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. . The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000100 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higgins J, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gurunath S, Pandian Z, Anderson RA et al. . Defining infertility—a systematic review of prevalence studies. Hum Reprod Update 2011;17:575–88. 10.1093/humupd/dmr015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D et al. . Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17:1–12. 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenland S, O'rourke K. On the bias produced by quality scores in meta-analysis, and a hierarchical view of proposed solutions. Biostatistics 2001;2:463–71. 10.1093/biostatistics/2.4.463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hedges L, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. New York: Academic Press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tuschen-Caffier B, Florin I, Krause W et al. . Cognitive-behavioral therapy for idiopathic infertile couples. Psychother Psychosom 1999;68:15–21. 10.1159/000012305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hozo S, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:13 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/5/13 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sterne JAC, Egger M, Moher D. Addressing reporting biases. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2008:297–333. 10.1002/9780470712184.ch10.10.1002/9780470712184.ch10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poole C, Greenland S. Random-effects meta-analyses are not always conservative. Am J Epidemiol 1999;150:469–75. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ et al. . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hedges LV, Pigott TD. The power of statistical tests in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods 2001;6:203–17. 10.1037/1082-989X.6.3.203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ioannidis JP, Trikalinos TA. The appropriateness of asymmetry tests for publication bias in meta-analyses: a large survey. CMAJ 2007;176:1091–6. 10.1503/cmaj.060410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Copas J, Shi JQ. Meta-analysis, funnel plots and sensitivity analysis. Biostatistics 2000;1:247–62. 10.1093/biostatistics/1.3.247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deeks JJ, Macaskill P, Irwig L. The performance of tests of publication bias and other sample size effects in systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy was assessed. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:882–93. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M et al. . Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosenthal R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychol Bull 1979;86:638–41. 10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.638 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2000;56:455–63. 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]