Abstract

Objectives

The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act created incentives for adopting electronic health records (EHRs) for some healthcare organisations, but long-term care (LTC) facilities are excluded from those incentives. There are realisable benefits of EHR adoption in LTC facilities; however, there is limited research about this topic. The purpose of this systematic literature review is to identify EHR adoption factors for LTC facilities that are ineligible for the HITECH Act incentives.

Setting

We conducted systematic searches of Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Complete via Ebson B. Stephens Company (EBSCO Host), Google Scholar and the university library search engine to collect data about EHR adoption factors in LTC facilities since 2009.

Participants

Search results were filtered by date range, full text, English language and academic journals (n=22).

Interventions

Multiple members of the research team read each article to confirm applicability and study conclusions.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Researchers identified common themes across the literature: specifically facilitators and barriers to adoption of the EHR in LTC.

Results

Results identify facilitators and barriers associated with EHR adoption in LTC facilities. The most common facilitators include access to information and error reduction. The most prevalent barriers include initial costs, user perceptions and implementation problems.

Conclusions

Similarities span the system selection phases and implementation process; of those, cost was the most common mentioned. These commonalities should help leaders in LTC facilities align strategic decisions to EHR adoption. This review may be useful for decision-makers attempting successful EHR adoption, policymakers trying to increase adoption rates without expanding incentives and vendors that produce EHRs.

Keywords: HEALTH SERVICES ADMINISTRATION & MANAGEMENT

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study adds to a body of knowledge of electronic health record (EHR) adoption and contributes specifically to EHR adoption in long-term care.

Provides a systematic review, in accordance with PRISMA.

Queries three well known research databases using key terms registered with Medical Subject Headings (MeSH).

The researchers only queried five years of research, and an objective assessment of study bias was not conducted.

Selection bias will always exist in subjective decisions (inclusion criteria). Controls for selection bias were enacted; more than one author had to recommend inclusion of the article in the review, and multiple authors had to identify and agree on the enablers and barriers to adoption.

Introduction, background and significance

Incentives

The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009 created reimbursement incentives for US healthcare organisations that are using electronic health records (EHRs) in meaningful ways.1 Long-term care (LTC) facilities (as defined by the ARRA) are facility types excluded from the incentives including: skilled nursing homes, assisted living facilities, LTC hospitals, rehabilitation hospitals and psychiatric hospitals. Unfortunately, there has been no clear communication regarding reasons why ‘ineligible providers’ have been excluded from the incentives under the ARRA. This is despite a relatively large body of evidence showing that there is value in the use of EHR in LTC settings where it not only improves resident care, but also increases communications between providers, consultants, hospital, and nursing home staff.2 There is documentation that exists which alludes to Congress wanting to understand the extent to which ineligible providers work in settings which might receive EHR incentives under the ARRA.3 However, it should be noted that eligible providers (physicians for instance) were able to assign their incentive funding to a facility of their choice (whether or not that facility was an eligible provider), but no evidence exists to the extent of this assignment in the literature or to whom.3 This represents not only a potentially large amount of untrackable incentive funds under the ARRA, but also a source of statistical interference when ‘meaningful use’ is assessed.

While facilities eligible for these incentives demonstrate EHR adoption rates of about 12%, ineligible facilities have adoption rates of only 2–4%.4 Incentives and grants from the HITECH Act are clearly a major motivating factor for EHR adoption5; however, LTC facilities must bear the adoption costs on their own, which represents a significant barrier.5–15

Identification and definition of key terms

The American College of Hospital Executives (ACHE) defines LTC as “a continuum of medical and social services designed to support the needs of people living with chronic health problems that affect their ability to perform everyday activities.” LTC spans a continuum of “traditional medical services, social services, and housing.” Services in LTC have a significantly different aim than traditional acute care services. While acute-care services aim to restore the patient to health, LTC “aims to prevent deterioration and promote social adjustment to stages of decline” and it is delivered through a wide range of care givers and environments both in a healthcare facility and at home.16 A large majority (92%) of LTC facilities are privately owned and operated. The aging of the population creates an ever-increasing shortage of LTC beds per 1000 people aged 65 and over. Estimates show this trend will continue until the year 2030 with the percentage of persons aged 65 or over ballooning to 19% of the population.17 The broad definition from the ACHE could encompass a wider range than necessary for the purposes of this research. The research question we posited would only be appropriate for healthcare organisations that would have a use for the EHR. While we think that an EHR would be beneficial at all levels of care to compensate for the lack of a provider of continuity between levels of care, we also look pragmatically at the cost versus the benefit. Because funding for an EHR would come from each independent healthcare organisation in the USA, an assisted-living facility in the USA would not have a significant need for an EHR that manages a patient's entire continuum of care; the facility may only need to manage something as small as medication or diet, which would not justify the millions of dollars to implement an EHR solution. Those with the greatest need for an EHR would be those that manage the chronic conditions like a nursing home, or skilled nursing facility.

The taxonomy for the EHR widely varies: digital medical record, computerised patient record, electronic medical record, digital medical record, etc. For the purposes of this study, the term EHR will be used exclusively to speak to the longitudinal and interoperable capabilities of an electronic medical record. This practice is supported by the WHO.18 The inherent advantages of the EHR are that it can enable any certified, credentialed provider to access any patient record from any healthcare organisation, but the provider will only have access to the information necessary for the immediate incident of care. The EHR enables providers to see history, allergies and treatment regimens with trend analysis.19

In 2009, the US Government passed the ARRA, which included a significant section for healthcare intended to incentivise the adoption of the EHR. This section was called HITECH Act.1 The three phases of meaningful use consume IT strategies because of the HITECH Act's timeline for healthcare organisations to qualify for monetary incentives. Unfortunately, LTC facilities were not included in these incentives.

EHR adoption among facilities

LTC facilities that have adopted EHRs experience improvements in quality of care, documentation access, billing and reimbursement, and employee satisfaction and retention rates.5–15 20 Interoperable EHRs may be especially useful to LTC facilities during periods of transitional care, when coordination and communication with other healthcare organisations is critical to achieving the best health outcomes.21 EHRs are becoming more important for LTC facilities because increased demand for services from aging baby boomers is inevitable.22 While eligible organisations have the benefit of incentives to mitigate some costs in attaining these benefits, LTC facilities must bear the full cost. There is a dearth of research available to help decision-makers at LTC facilities make objective conclusions about adopting EHRs, which is why this review is critical to future research.

EHR impact

It is important to identify the factors that influence EHR adoption in LTC facilities that are not dependent on HITECH incentive payments. This study's focus is to identify what those adoption factors are, as well as discern the multitude of barriers those facilities face. While it is clear that implementing an EHR system could bring many benefits to organisations, realising those benefits in the beginning stages might not be possible for every LTC facility.

Objectives

The findings of this review will be useful to LTC facility administrators interested in adopting EHRs into their organisation by helping them identify barriers to overcome and opportunities to lever. Policymakers may also find the identified factors useful when attempting to increase EHR adoption in the LTC industry. Additionally, vendors can benefit from this article's information to design EHRs that are more useful for LTC facilities.

Methods

Data

Data for this review were gathered using three separate databases: Google Scholar, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Complete via Ebson B. Stephens Company (EBSCO Host), and PubMed (which queries MEDLINE). Search criteria focused on EHR adoption in LTC. The authors independently reviewed the articles identified during the search and independently summarised findings germane to this review. Following independent reviews, authors compared and discussed the articles and reason for inclusion in the study. Articles were only included if selected by at least two reviewers. The comparable search criteria demonstrated the authors had a similar understanding of the research problem.

Sample

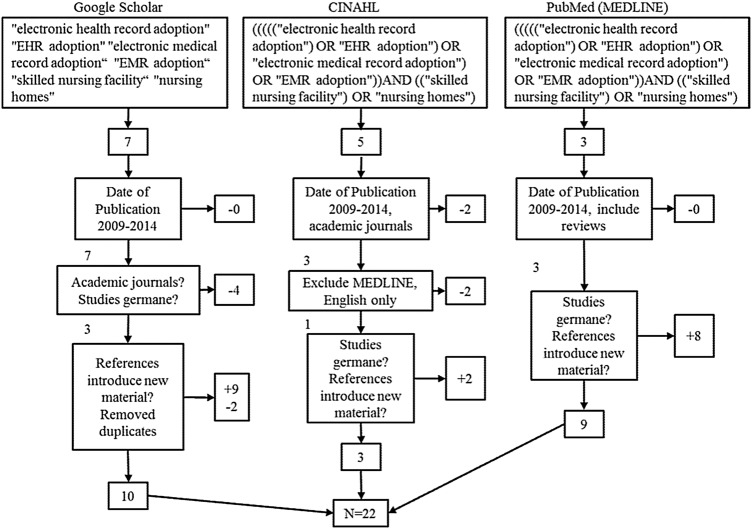

Research databases were queried using terms from the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Although multiple terms appeared for the EHR, the only heading listed in MeSH for LTC was ‘long-term care.’ Several exclusion criteria were also specified: The authors began with broad database searches then narrowed the criteria to identify the most commonly mentioned factors listed in the articles. This method avoids excluding relevant data by too narrowly defining initial search criteria. Searches were limited to peer-reviewed journal articles in US-based English language from 2009–2014 (n=16). This process is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the manuscript-selection process for the review (EHR, electronic health record; EMR, electronic medical record).

Searches continued until the results reached saturation by repeating information about costs, perceptions and implementation.

Results

Table of findings

The findings were summarised and inserted into the facilitators and barriers table after the authors chose articles to create the literature review. All duplicate articles were accounted for and consolidated before the findings table was created. The authors then reanalysed the articles and identified the individual factors affecting EHR adoption in LTC facilities after the articles reached information saturation. These factors were then compiled into a frequency table to aid in the analysis. An objective assessment of study bias was not conducted in this review. Results are summarised in table 1. An expanded version of this table is provided as an online supplementary file. It augments the information below with the title of each study and study characteristics such as the study design and data sources.

Table 1.

Results from the review of the literature

| Authors | Facilitators | Barriers |

|---|---|---|

| Wolf et al4 | ▸ Emerging payment methods could encourage EHR adoption ▸ ‘Quality Improvement Organizations’ may increase adoption because they provide technical support that many LTC facilities need |

▸ HITECH incentives only focus on acute care and primary physicians ▸ Expanding the incentives to LTC facilities may be too costly |

| Wang and Biedermann5 | ▸ Anticipating state and federal requirements ▸ Good communication between vendors and LTC facilities ▸ Education and training programmes |

▸ Lack of initial investment resources ▸ No technical infrastructure ▸ Not enough time to implement the EHR ▸ Lack of space for the new system |

| Resnick, et al6 | ▸ Error reduction ▸ Quality ▸ Efficiency ▸ Better health outcomes |

▸ Cost ▸ Complex systems (implementation) ▸ No standards (external) |

| Davidson7 | ▸ Comprehensive implementation planning ▸ Governmental initiatives ▸ Management and staff support |

▸ Cost ▸ Privacy issues ▸ Incorrect vendor |

| Hamid and Cline8 | ▸ EHR satisfaction increases when the users understand the benefits ▸ Supportive management ▸ Training programmes |

▸ Cost ▸ Perceived lack of usefulness ▸ Time consuming |

| Alexander and Madsen9 | ▸ Improve clinical decision-making ▸ Earlier intervention ▸ Time savings |

▸ IT sophistication negatively correlated with detection of incontinence (implementation issue?) |

| Phillips et al10 | ▸ Government financial incentives ▸ Reduced errors and adverse drug events ▸ Including users in the design and implementation process |

▸ Adoption costs ▸ Efficiency outcomes were inconsistent ▸ Incongruent cost savings ▸ Lack of interoperability ▸ Fear of changing the facility culture |

| Wilkins11 | ▸ Training and learning the system increases adoption ▸ Understanding the usefulness of the EHR technology |

▸ Facility size ▸ Lack of change agents or leaders in the facility ▸ Lack of interoperability ▸ Cost ▸ Resistance to change |

| Filipova12 | ▸ Federal and state government incentives or policy initiatives could offset financial barriers ▸ Aligning organisational strategic plans could also encourage adoption |

▸ Financial barriers like no capital to implement an EHR and the cost of hardware and infrastructure ▸ Organisational barriers ▸ Legal and regulatory barriers ▸ Technological barriers ▸ Network barriers |

| Bezboruah et al13 | ▸ Institutional pressure like anticipated regulations and competition pressures increase EHR adoption | ▸ Cost of the electronic system and projected upgrades ▸ Leaders perceiving staff's resistance to change ▸ Misunderstanding how EHRs could be useful or not having enough information to choose the right system |

| Cherry14 | ▸ Fast-growing elder populations mean quality of care in LTC facilities must be addressed with EHRs ▸ A strong implementation plan within the facility that aligns with strategic plans ▸ Initial and follow-up training programmes ▸ A perception shift about the benefits of EHR adoption |

▸ Cost and a lack of capital resources ▸ Lack of industry standards ▸ Complicated implementation processes ▸ Lack of technical support ▸ Not enough evidence to support EHR's proposed benefits |

| Grabenbaueret al15 | ▸ Improved communication ▸ Patient data access and sharing |

▸ Cost ▸ Reduced time with patients ▸ Currently EHRs do not impact population health |

| Cherry et al20 | ▸ Rapid patient record retrieval ▸ Better document consistency, quality and accuracy ▸ Improvements in employee satisfaction and retention ▸ Better patient assessments, oversight and order processing ▸ Better time management |

▸ Technology and maintenance problems like downtime or learning the new system. ▸ Residents thought providers were more focused on the computers than on them |

| Tabar23 | ▸ Perceptions are changing in LTC; EHRs are becoming a cost of doing business | ▸ Most EHRs were built for acute care and LTC facilities had trouble finding a system that met the organisation's needs |

| Vendor group develops EHR code of conduct24 | ▸ Cost reductions ▸ Improve patient outcomes ▸ State programmes could help fund a facility's EHR adoption |

|

| Yu et al25 | ▸ Continuous training ▸ Open dialogue with vendors ▸ Balancing EHR accuracy with patient care ▸ Facilities should have all paper or all electronic systems |

▸ Staff resisted the new system because personal perceptions about their age, lack of documentation skills or other reasons created limitations ▸ Information management became too difficult and documents lacked consistency ▸ Providers complained about spending less time with residents |

| Hamann and Bezboruah26 | ▸ Non-profit facilities were 40% more likely to adopt EHRs ▸ Non-profits have more regulations, so may need the benefits of EHRs |

▸ For-profit facilities lagged behind in EHR adoption rates ▸ Fewer regulations enable for-profit facilities to invest in cost-effective endeavours and avoid the expense of EHR implementation |

| Vest et al27 | ▸ More EHR vendors ▸ Trends show electronic record use is on the rise ▸ Meaningful use makes EHRs more prevalent |

▸ Lagging widespread EHR adoption ▸ Misaligned incentives |

| Weaver S28 | ▸ Error reduction (quality) ▸ Improved efficiency ▸ Consumer (user) perceptions ▸ Improved health outcomes |

▸ Difficulties transitioning from paper to EHR (implementation) ▸ Training becomes paramount |

| Gruber et al29 | ▸ Strong implementation team ▸ Train and prepare all users ▸ Have ample space for training ▸ Communicate often and thoroughly ▸ Set goals, tasks and schedules for the implementation ▸ Reduced errors ▸ Improved documentation |

▸ Minor increases in operating expenses |

| Holup et al30 | ▸ Rapidly aging populations stresses the need to create interoperable, coordinated EHRs for LTC facilities | ▸ LTC EHRs are not as comprehensive as acute care EHRs |

| Holup et al31 | ▸ Created better health outcomes ▸ Reduced extra costs ▸ Improved delivery and quality ▸ An increasing elder population makes implementing EHRs a necessity ▸ Nonprofits were more likely to utilise EHRs |

▸ High initial investment means slower adoption in facilities that cannot afford the EHR system, which slows the rate of becoming better integrated with acute care ▸ Facility characteristics determine EHR adoption |

EHR, electronic health record; HITECH, Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health; LTC, long-term care.

An analysis of the articles in the systematic literature review revealed multiple facilitators and barriers to adopting an EHR. The review's focus was on LTC facility facilitators and barriers. The facilitators to adoption included ease of access to information, error reduction, long-run cost savings, efficiency and information security. The barriers to adaptation included increasing costs, users’ negative perception, cultural changes, lack of proper training and lack of implementation proper planning.

Facilitators

The determined facilitators associated with EHR adoption were: access and transfer of information, long-run cost savings, error reduction, clinical and administrative efficiency, project planning, security, user perceptions, facility characteristics, health outcomes, time savings and staff retention. The facilitators also have narrowed subsections throughout the articles. The benefits LTC facilities faced after adopting EHRs are connected to the facilitators. For example, facilities realised an ability to get to patient records quickly and easily, which is related to access and transfer of information.7 8 15 Cost savings looked at the long-run facility savings and how an EHR is an investment with benefits that take time to realise.23 24 Error reduction was another benefit of using EHRs, expressed as fewer prescription errors, more patient medication and allergy alerts and more overall health safeguards.8 9 20 Efficiency enabled rapid information exchange through administrative channels, improved productivity and consistency, and better communication between clinical and administrative departments.9–11 15 20

Barriers

The barriers varied in topic specification. The broad categories determined from the literature review were: cost savings, user perception, implementation issues, external factors, training, facility characteristics, cultural change, project planning, security, staff retention and system issues. Each broader category has sub-issues that LTC facilities face during EHR adoption.

Of the sub-issues, cost barriers were a consistent concern because adopting and implementing an EHR requires a substantial initial investment. Other cost concerns stem from the lack of funding for LTC facilities, future upgrades and maintenance that will be necessary to successfully use the EHR.8 13

User perception barriers included issues with professional and public acceptance of the new system as well as functionality problems.8–10 Implementation barriers were lack of complete understanding from the staff, too little training during and after implementation, and lack of time for implementation and understanding.5 6 14 20 The external factors that present implementation problems were employee recruitment, lack of industry standards, facility location and impact on the population.5 14 15 These facilitators and barriers are summarised in table 2.

Table 2.

Affinity matrix identifying frequency of factors listed in the literature

| Factors | Total occurrences |

|---|---|

| Facilitators | |

| Error reduction | 7 |

| Clinical and administrative efficiency | 7 |

| Cost savings | 6 |

| Health outcomes | 6 |

| Access and transfer to information | 5 |

| Project planning | 4 |

| User perceptions | 4 |

| Security | 3 |

| Facility characteristics | 3 |

| Time saving | 3 |

| Barriers | |

| Cost | 10 |

| User perceptions | 8 |

| Implementation issues | 8 |

| External factors | 6 |

| Training | 5 |

| Facility characteristics | 4 |

| Cultural change | 2 |

| Project planning | 2 |

| Security | 2 |

| Staff retention | 1 |

| System issues | 1 |

Discussion

Many factors determine the adoption of EHR technology in LTC facilities. The authors found the cost, perceptions and implementation process as the most significant factors that affect EHR adoption by LTC facilities. By considering these factors and the degree to which a facility can manipulate them, it may be possible to increase EHR use among LTC facilities to create better outcomes, reduce costs and increase coordination of care.

Population

The rapid increase in LTC residency exemplifies the need for facilities to be efficient, coordinated, and have good patient outcomes. Quality measures would increase if EHRs were more prevalent in LTC facilities, but vendors’ main focus is creating acute care EHRs10 21; which make current EHRs impractical for most LTC facilities.10 11 23 The adoption rate could increase if there were standardisation in the EHR market,10 which would make systems easier to use across different facilities.

Vendors would benefit from connecting with LTC leaders to understand how EHRs fit LTC strategic planning. A useful EHR helps LTC facilities improve quality, reduce errors, aids with billing and reimbursement, increases employee satisfaction, and may also increase employee retention.6 8 13 LTC facilities need EHRs that are interoperable with other hospital systems so transfers and coordination of care become easier and have less errors. Vendors would benefit from understanding how LTC facilities use EHRs and how to make them more compatible for LTC needs.

Cost

The cost of implementing the EHR was the most prevalent barrier. Many facilities may reject acquiring or installing an EHR because the initial cost is so high5–15 and maintaining and upgrading the EHR may also be too costly.10 13 20 Lack of initial capital could inhibit the first step of considering adopting an EHR. There was a general theme that if LTC facilities had funding, they could become meaningful EHR users more quickly. While cost is a barrier, it is important to point out that many studies stressed the need for LTC facilities to be coordinated with acute care hospitals to run more efficiently and productively. Finding the money required to execute an EHR is critical to LTC facilities gaining the information it needs to make improved clinical decisions.

Cost was a running topic among many studies because the HITECH Act's meaningful use incentives do not include LTC facilities. LTC facilities lack the ability to participate in the HITECH incentive programme, yet there is a gap in research that explores different funding alternatives for LTC.

Perceptions

Another major factor that determines if an EHR will be adopted by an LTC facility is the administrative and clinical user perceptions.5 8 10 13–15 20 25 Perception can manifest as something that can hinder or help EHR adoption at LTC facilities. Rejecting an EHR may be due to a lack of understanding about the user benefits,8 which might be connected to fear of change.13 The perception that an EHR system will simply not be useful could also be a result of marketing shortfalls on the part of EHR vendors. Lack of usefulness may also result from not effectively implementing the system and failing to achieve expected benefits. However, concerns that the system will be difficult to use can be addressed by selecting a system with a focus on user interfaces. Furthermore, misunderstanding EHR benefits may lead to a perception that using this technology will reduce the amount of time physicians and nurses spend with residents.15 20 25 A surprising finding was that the negative impact perceived by the providers was due to a lack of training.6 14 15

Training helps change negative perceptions and increases the likelihood of adopting an EHR; a theme among some articles was that initial, follow-up, and ongoing training is the best method to ensure broad EHR acceptance.8 14 15 Training could also help people who lack general computer skills, documentation skills, and people who may find the systems difficult to navigate.25 Having the funds to conduct proper training will determine whether users can learn to accept the new system, which further stresses the need for funding.

Administrators’ perceptions about the changing regulatory and competitive LTC environment may present some EHR adoption opportunities. Reasons facilities chose to adopt an EHR include anticipation about increases in the regulatory environment and changes to reimbursement.4 13 Some nursing home administrators feared increased regulations in the industry, and this prompted EHR adoption to prepare for a possible mandate.13 Others chose to adopt EHRs due to emerging payment methods, such as bundled payments, which require better coordination of care with outside entities to receive higher reimbursements.4 The competitive LTC environment steered some organisations to adopt EHRs to emulate competitors’ EHR success.13 The competitive advantage of EHRs should be explained to decision-makers so they can confidently adopt the systems. Additionally, policymakers must offer incentives along with the increases in regulations and changes in reimbursement; unfunded mandates would degrade EHR perceptions in LTC.

Implementation

Adopting an EHR relies heavily on the execution of the implementation process. Many studies pointed to having a strategic plan that accounts for the size, governance, costs, facility needs, and regulatory requirements of the internal and external environments.8 10 13 14 Also significant is having the right people to implement the system; this should include a committee, strong leadership, trainers and the right vendor. Creating a successful implementation plan could make or break the EHR project. Some facilities found not having LTC industry standards was a barrier to adoption because they did not have a benchmark to use for an implementation plan.6 14 This finding's implication is a need to involve interest groups to create industry standards to help LTC facilities adopt EHRs in the future.

Facilitators

LTC facilities may begin to realise the ongoing benefits of EHR adoption after an organisation weighs the EHR adoption barriers, determines whether it aligns with the strategic plan, and decides to make the steps to implementation. The facilitator's overarching theme was an ultimate increase in efficiency for the entire organisation. This finding is interesting because the path to implementing an EHR can disrupt business in the beginning stages by taking time to train employees, integrate information, as well as cost the facility ample money. If decision-makers prioritise EHR adoption with an implementation plan, then the organisation is more likely to realise facilitators such as cost savings, better transfer of information and error reduction.

Decision-makers should recognise the EHR facilitators, find ways to overcome the initial costs, and rely on research that indicates recognisable savings of successful system implementation. As with all decisions, there are costs and benefits to LTC facilities widely adopting EHRs, but the research suggests EHRs may soon be heavily utilised, and adopting one now could help prepare staff and residents for this inevitable change.

Limitations

This paper provides a review of current and comprehensive data about EHR adoption factors for LTC facilities, and will help those facilities understand the costs and benefits of adopting an EHR system.

This study generalised all LTC facilities together, which bolsters the study's external validity because many other articles also conducted research this way. LTC facilities can be lumped together because they all lack HITECH incentives. The differences between the facilities are size, location and reimbursement structure. The authors found different facilities adopted EHRs at various rates, but the difference was not relevant to this study's results because all LTC facilities have similar obstacles to adoption.

The lack of evidence written about EHR adoption among LTC facilities and the search database limits led to the exhaustive nature of adoption factors of the study. This study was limited to only current research, which helped create a comparison for LTC facilities that want to implement an EHR in today's environment.

Conclusions

It is important to examine factors affecting EHR adoption in LTC facilities because those facilities do not receive HITECH incentives. This study identified numerous facilitating factors and barriers through a systematic review of current articles in three scholarly databases. This information can be useful for decision-makers attempting successful EHR adoption in their LTC facility, policymakers trying to increase adoption rates without expanding incentives and vendors who wish to create EHRs that coordinate with LTC.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CSK (20%) directed the research, taught students how to conduct and present a systematic literature review, read all articles, added comments about the articles, performed final editing of the final product and serves as the corresponding author. MM (20%) served as the LTC advisor, added comments about the articles, and contributed to final editing of the product. VA (20%) conducted part of the literature review, read the articles, wrote a significant portion of the introduction/background, wrote the entire methods section, created the figure for the methods section and wrote portions of the discussion. EC (20%) conducted part of the literature review, read the articles, wrote portions of the discussion, wrote all of the limitations and served as the master editor for the paper. AW (20%) conducted part of the literature review, read the articles, researched the chosen journal, created the summary and frequency tables, wrote the entire results section and formatted the final paper to journal specifications. CSK and MM provided guidance, advice, and independent analysis to validate that of the graduate students.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There was no sharing of data. All research used was original. This research was originally submitted to the US Journal of American Medical Informatics Association, but it was rejected. The review was rewritten based on input from reviewers from JAMIA. No portion of this research is currently with another publisher, nor has any of the research been published.

References

- 1.2009. Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, 42 U.S.C. § 201. http://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/hitech_act_excerpt_from_arra_with_index.pdf (accessed 18 Mar 2014). WebCite. http://www.webcitation.org/6OApfh2QK.

- 2.Brandeis GH, Hogan M, Murphy M et al. . Electronic health record implementation in community nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2007;8:31–4. 10.1016/j.jamda.2006.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. EHR Payment Incentives for Providers Ineligible for Payment Incentives and Other Funding Study. http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/2013/EHRPIap.shtml#appendD (accessed 9 Sep 2014).

- 4.Wolf L, Harvell J, Jha AK. Hospitals ineligible for federal meaningful-use incentives have dismally low rates of adoption of electronic health records. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:505–13. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang T, Biedermann S. Adoption and utilization of electronic health record systems by long-term care facilities in Texas. Perspect Health Inf Manag 2012;9:1g. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Resnick HE, Manard BB, Stone RI et al. . Use of electronic information systems in nursing homes: United States, 2004. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009;16:179–86. 10.1197/jamia.M2955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson J. Electronic medical records: what they are and how they will revolutionize the delivery of resident care...first of a two-part series. Can Nurs Home 2009;20:15–6. CINAHL Complete, Ipswich, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamid F, Cline T. Providers’ acceptance factors and their perceived barriers to electronic health record (EHR) adoption. J Nurs Inform 2013;17:1–11. CINAHL Complete, Ipswich, MA. Accessed July 10, 2014. Permalink. http://libproxy.txstate.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=2012367240&site=ehost-live [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander GL, Madsen R. IT sophistication and quality measures in nursing homes. J Gerontol Nurs 2009;35:22 10.3928/00989134-20090527-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips K, Wheeler C, Campbell J et al. . Electronic medical records in long-term care. J Hosp Mark Public Relations 2010;20:131–42. 10.1080/15390942.2010.493377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkins M. Factors influencing acceptance of electronic health records in hospitals. Perspect Health Inf Manag 2009;6:1f. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filipova AA. Electronic health records use and barriers and benefits to use in skilled nursing facilities. Comput Inform Nurs 2013;31:305–18. 10.1097/NXN.0b013e318295e40e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bezboruah KC, Hamann DJ, Smith JD. Management attitudes and technology adoption in long-term care facilities. J Health Organ Manag 2014;28:344–65. 10.1108/JHOM-11-2011-0118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherry B. Assessing organizational readiness for electronic health record adoption in long-term care facilities. J Gerontol Nurs 2011;37:14–19. 10.3928/00989134-20110831-06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grabenbauer L, Skinner A, Windle J. Electronic health record adoption—maybe it's not about the money: physician super-users, electronic health records and patient care. Appl Clin Inform 2011;2:460–71. 10.4338/ACI-2011-05-RA-0033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCall N. Long-term care: definition, demand, cost, and financing. http://www.ache.org/PUBS/1mccall.pdf, Webcitation. http://www.webcitation.org/6SKzjPXVl.

- 17.Association on aging. http://www.aoa.gov/Aging_Statistics/ (accessed 4 Sep 2014). Webcitation. http://www.webcitation.org/6SL0fI4rt

- 18. Institute of Medicine, key capabilities of an electronic health record, Institute of Medicine 2003 Jul. http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2003/Key-Capabilities-of-an-Electronic-Health-Record-System.aspx (accessed 4 Sep 2014). WebCite. http://www.webcitation.org/6ODtL6HKG.

- 19.U.S. Health and Human Services. Learn EHR basics. http://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/learn-ehr-basics (accessed 4 Sep 2014). Webcitation. http://www.webcitation.org/6SL21pUQO

- 20.Cherry BJ, Ford EW, Peterson LT. Experiences with electronic health records: early adopters in long-term care facilities. Health Care Manage Rev 2011;36:265–74. 10.1097/HMR.0b013e31820e110f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tripp JS, Narus SP, Magill MK et al. . Evaluating the accuracy of existing EMR data as predictors of follow-up providers. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2008;15:787–90. 10.1197/jamia.M2753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robison J, Shugrue N, Fortinsky RH et al. . Long-term supports and services planning for the future: implications from a statewide survey of baby boomers and older adults. Gerontologist 2014;54:297–313. 10.1093/geront/gnt094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tabar P. Why EHRs matter to LTC's future. Long-Term Living: For the Continuing Care Professional, 2013;62:14–16. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vendor Group Develops EHR Code of Conduct. Journal of AHIMA 2013;84:12–13. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu P, Zhang Y, Gong Y et al. . Unintended adverse consequences of introducing electronic health records in residential aged care homes. Int J Med Inform 2013;82:772–88. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2013.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamann DJ, Bezboruah KC. Utilization of technology by long-term care providers comparisons between for-profit and nonprofit institutions. J Aging Health 2013;25:535–54. 10.1177/0898264313480238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vest JR, Yoon J, Bossak BH. Changes to the electronic health records market in light of health information technology certification and meaningful use. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013;20:227–32. 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Weaver S, Dick M, Dougherty M, et al. EHR adoption in LTC and the HIM value. Journal of AHIMA/American Health Information Management Association 2011;82:46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gruber N, Darragh J, Puccia P et al. . Embracing change to improve performance: implementation of an electronic health record system. Long Term Living: For the Continuing Care Professional, 2010;59:28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holup AA, Dobbs D, Temple A et al. . Going digital adoption of electronic health records in assisted living facilities. J Appl Gerontol 2014;33:494–504. 10.1177/0733464812454009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holup AA, Dobbs D, Meng H et al. . Facility characteristics associated with the use of electronic health records in residential care facilities. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013;20:787–91. 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.