Abstract

Objectives

To develop and validate a new algorithm to identify patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and estimate disease prevalence using administrative health databases (AHDs) of the Italian Lombardy region.

Design

Case–control and cohort diagnostic accuracy study.

Methods

In a randomly selected sample of 827 patients drawn from a tertiary rheumatology centre (training set), clinically validated diagnoses were linked to administrative data including diagnostic codes and drug prescriptions. An algorithm in steps of decreasing specificity was developed and its accuracy assessed calculating sensitivity/specificity, positive predictive value (PPV)/negative predictive value, with corresponding CIs. The algorithm was applied to two validating sets: 106 patients from a secondary rheumatology centre and 6087 participants from the primary care. Alternative algorithms were developed to increase PPV at population level. Crude and adjusted prevalence estimates taking into account algorithm misclassification rates were obtained for the Lombardy region.

Results

The algorithms included: RA certification by a rheumatologist, certification for other autoimmune diseases by specialists, RA code in the hospital discharge form, prescription of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and oral glucocorticoids. In the training set, a four-step algorithm identified clinically diagnosed RA cases with a sensitivity of 96.3 (95% CI 93.6 to 98.2) and a specificity of 90.3 (87.4 to 92.7). Both external validations showed highly consistent results. More specific algorithms achieved >80% PPV at the population level. The crude RA prevalence in Lombardy was 0.52%, and estimates adjusted for misclassification ranged from 0.31% (95% CI 0.14% to 0.42%) to 0.37% (0.25% to 0.47%).

Conclusions

AHDs are valuable tools for the identification of RA cases at the population level, and allow estimation of disease prevalence and to select retrospective cohorts.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provides a complete validation of classification algorithms for the identification of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) at the population level through healthcare administrative databases.

Two different approaches were applied in this study to estimate RA prevalence accounting for misclassification inherent to the classification algorithm.

Classification of disease according to algorithms from administrative data is setting-specific and not directly transferred to other systems.

Proper classification algorithm validations are useful to develop consistent instruments to compare disease burden in different healthcare systems.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic autoimmune disease that is associated with development of disability, increased mortality and significant costs to society.1 Population-based studies help to monitor disease burden, to evaluate long-term consequences of the disease and its treatments, and to assess quality of care, for both research and governance purposes.2

The increasing diffusion and completeness of administrative health databases (AHDs)—which record healthcare services dispensed to all members of a specific population—provide a straightforward way to perform such population-based studies in RA.3–5 The validity of AHD studies primarily relies on the diagnostic accuracy of case definition. The huge methodological variability of validation studies of AHD-based classification algorithms in RA makes it difficult to evaluate the potentialities of AHD for population studies of RA.6–16

The majority of the studies in RA develop classification algorithm sampling from populations with high prevalence of RA (eg, rheumatology clinics), focusing on the positive predictive value (PPV)—the probability of being a true case if classified as a potential one by AHD-based criteria. Even if high PPV was achieved in this setting, it does not reflect the performance achievable in the general population, where the prevalence of RA is 30–50-fold lower. Thus, in order to develop a valid instrument to perform a population study, a validation study sampling from the same population where it will be applied is highly informative. Nevertheless, no study has currently provided a full validation of algorithms developed for the classification of RA by AHD at population level.15

The RECord linkage On Rheumatic Diseases (RECORD) study—promoted by the Italian Society for Rheumatology—aims to set up a national surveillance system to monitor the health burden of rheumatic diseases in Italy using data from AHD. The RECORD study of RA is structured in three phases: the first phase aims to evaluate the frequency of the disease; the second phase to evaluate the impact of the disease and its treatment on hard disease outcomes at population level and the third phase to evaluate the quality of care delivered to patients with RA.

In order to reach the objectives of the first step of the RECORD study, we report the methodological approach and the results of the development and validation of different algorithms of classification for RA at different levels of the healthcare system, including primary care. We linked clinically validated diagnoses of randomly selected samples of cases and controls with the AHD of the Lombardy region (Italy). The prevalence of RA was then derived both as crude estimate and adjusting for inherent misclassification.

Patients and methods

Reporting of this study compiles with the guidelines for diagnostic and validation studies of health administrative data.17 18

Study design and samples

Training set

A random sample of visits of 900 outpatients (300 cases with RA and 600 controls with rheumatic diseases other than RA, on the basis of the diagnosis reported on the electronic medical records) aged over 16 years and assisted by a tertiary rheumatology clinic (Rheumatology Unit, IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo Foundation, Pavia) between 2007 and 2010 was extracted from the medical record database of this centre according to a case–control diagnostic design nested in the resident population of Pavia.19

A sample size >700 participants with a proportion of one-third of cases in the training set was defined to precisely estimate negative predictive value (NPV) >0.95 as well as PPV >0.50, setting α at 0.05 and β at 0.8, as proposed by Steinberg et al20 for case–control diagnostic studies.

Validating sets

Two different samples were drawn for validation purposes: one from a secondary rheumatology centre and one from the primary care (general population sample) within the same catchment area. In these validating samples, a cohort diagnostic study design was applied.21 The first validating set included a random sample of 138 patients from the electronic medical records of the Rheumatology outpatient clinic of the Clinical Institute Beato Matteo of Vigevano, a secondary care rheumatology clinic. A second validating set included all the 6087 participants extracted from the primary care electronic medical records of a convenience sample of six primary care physicians of the Local Health Authority (LHA) of Pavia.

Participants gave their consent to the processing of their personal data.

Test methods

Reference standard

The clinical diagnosis from medical records was considered the reference standard. Diagnoses were clinically validated by an external investigator (GiCa), who was unaware of the content and results of the algorithm. When the diagnosis was unclear or varied over time, patients were classified according to specific classification criteria,22 cumulatively applied until the date of the randomly selected visit, based on a data collection form including gender, age, disease duration, morning stiffness, joint involvement, rheumatoid factor and X-ray abnormalities.

Administrative healthcare database variables and record linkage

AHDs are automated systems of databases consisting of: (1) an archive of all residents receiving National Health Service (NHS) assistance (virtually the whole resident population) reporting demographic and administrative data; (2) an archive including all the certifications of chronic diseases for the exemption from co-payment; (3) an archive of all hospital discharge forms (HDFs) from public or private hospitals, reporting all diagnoses related to the hospitalisation; (4) an archive of all outpatient drug prescriptions reimbursable by the NHS.

The AHD variables useful for the identification of RA cases were defined a priori through a consensus process, informed by a literature review, held in February 2012 and involving five clinicians, one epidemiologist, three database owners and two statisticians. The literature was searched via PubMed using a combination of free-text and MeSH terms regarding ‘rheumatoid arthritis’ and ‘administrative database’. The relevant variables were selected among a list of items extracted from the retrieved literature3 6–12 23 (see online supplementary appendix 1). These variables represented the set of potential index texts to be included in the classification algorithm: RA certification by a rheumatologist and certification for other chronic autoimmune diseases (ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis, connective tissue diseases, systemic vasculitis, inflammatory bowel diseases), the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD9-CM) code 714.0 in the HDF, prescription of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) including biologics and oral glucocorticoids, outpatient diagnostic procedures, outpatient visits, diagnostic procedures in the HDF, blood tests and instrumental tests (as radiographs).

The following items were selected to be included in the algorithm: RA certification by rheumatologist, absence of certification for other chronic autoimmune diseases, ICD9-CM code 714.0 in the HDF, prescription of DMARDs including biologics and oral glucocorticoids (see online supplementary appendix 2).

Administrative data (selected items needed to create the algorithm) relative to patients included in rheumatological samples and general population sample were extracted from the data warehouse of Pavia's LHA within an interval of ±1 year over the index date (ie, date of clinical assessment ranging from 2006 to 2011) for rheumatological samples, and ±1 year over 1 September 2011 for the primary care sample.

Clinically validated diagnoses and administrative data from the LHA of Pavia were linked using deterministic record linkage through an encrypted unique identifier code (only participants successfully linked were retained for the analyses). A parallel extraction from the regional data warehouse from 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2010 only included the items needed for the classification according to the developed algorithm, in order to estimate the prevalence of RA.

Statistical methods

Development and validation of the algorithm

For each variable identified in the consensus-based phase, sensitivity and specificity were evaluated in the training set. Combining a priori knowledge and empirical estimates of sensitivity and specificity of each variable, a first candidate algorithm was developed, including in the first step variables with high specificity. The algorithm was then changed by sequentially including other variables with lower specificity but higher sensitivity. This process was stopped when a high sensitivity was reached at the expense of the least decrease in specificity.

For example, RA certification by rheumatologist, ICD9-CM code 714 in HDF and some drugs, such as leflunomide and abatacept, showed high specificity. Knowing that other drugs, such as tocilizumab and gold salts also have high specificity, we combined these items in the first step. Later, items that are more sensitive and less specific, such as methotrexate, antimalarial drugs and glucocorticoids, were combined in the successive steps.

Once the algorithm was fully defined, its overall accuracy was assessed by estimating sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV—with exact 95% CIs.

The robustness of these estimates was tested in the training set by bootstrap procedure, using 1000 samples extracted with replacement.

Two automated statistical procedures were also applied: a backward variable selection approach applied to a parametric penalised logistic regression model with multiple interaction terms and non-parametric classification trees.

A sensitivity analysis was performed by considering alternative algorithms stratified by age (with a cut-off at 65 years) and a narrower temporal range of ±6 months from the index date for the extraction of the selected variables.

Two external fully independent validations21 were carried out using data sets from different levels of healthcare: a secondary rheumatology centre and primary care. The performance of the algorithm was tested estimating sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV.

Estimation of disease prevalence

To estimate the prevalence of RA in Lombardy (an Italian region of about nine million residents) in 2010, the final algorithm was applied to the required variables extracted from the AHD of Lombardy, which have the same structure of the AHD of the Pavia LHA (ie, an archive of: residents, certifications of exemption, hospital discharges and of outpatient drug prescriptions). The target population consisted of all residents aged 16 years or older.

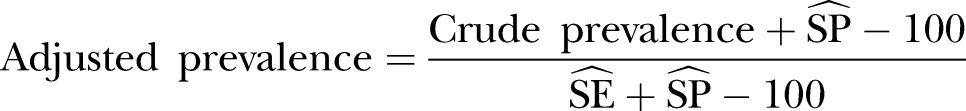

The crude prevalence estimate was adjusted for the impact of misclassification due to possible classification errors of the algorithm, quantified during the validation phase, by applying two different methods. The first method—proposed by Gladen and Rogan—is based on a direct relationship that expresses the adjusted value of the prevalence as a function of the crude prevalence, and the sensitivity and specificity of the algorithm (equation 1). Using the estimates of sensitivity and specificity derived from the validation study in the general population sample, the crude prevalence was corrected for the impact of misclassification and 95% CI was calculated.24

|

1 |

The second method—proposed by Joseph et al25—provides a more precise adjusted estimate by giving preference only to the most plausible range of values for the parameters of interest (prevalence, and sensitivity and specificity of the algorithm). Specifically, following the Bayesian framework, an initial quantification of the plausibility of each possible value of the parameters of interest was summarised in a probability distribution (prior distribution), based on estimates of sensitivity and specificity obtained from the validation study in the general population sample and on prevalence obtained from previous population studies.26–29 The prior distribution was then updated in light of the observed data through their likelihood, leading to a posterior distribution, and the mean, and 2.5% and 97.5% centiles of the posterior distribution, provide an estimate of the parameters and a corresponding credibility interval.

Data management and statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software (V.9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA), R Statistical Software (Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and WinBUGS software V.1.4.3.30

Results

Study samples

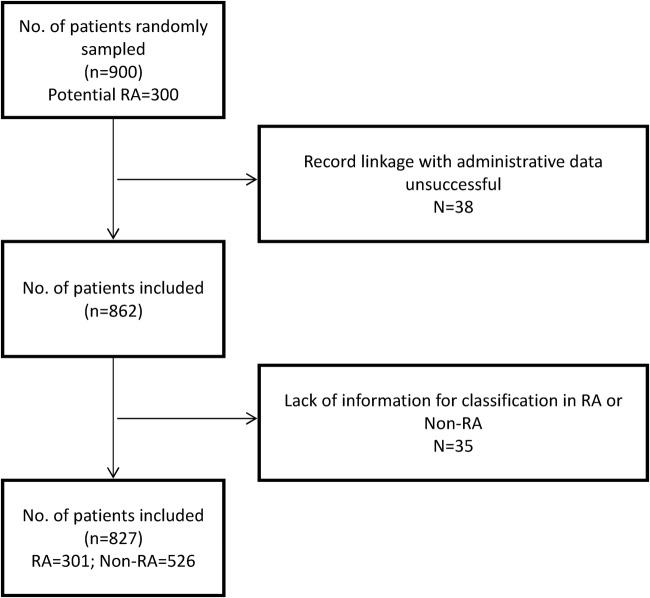

In the first rheumatological sample (training sample), in 862/900 participants (96%) record linkage between the clinical data set and administrative data was successful. Complete information for diagnosis validation (criteria for classification in RA e non-RA) was available for 827/862 participants (96%; figure 1). Demographic, disease and treatment characteristics are reported in table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the training set sample (RA, rheumatoid arthritis).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the training sample

| Characteristic | RA (n=301) | Non-RA (n=526) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 66.8 (13.1) | 57.7 (15.7) |

| Female gender, n (%) | 218 (72.4) | 405 (77) |

| Disease duration <2 years, n (%) | 81* (27.6) | |

| Rheumatoid factor positive, n (%) | 151† (54.4) | |

| NSAID or COX-2 inhibitor, n (%) | 198 (65.8) | 298 (56.7) |

| Glucocorticoids, n (%) | 228 (75.8) | 178 (33.8) |

| DMARDs | ||

| Methotrexate, n (%) | 182 (60.5) | 31 (5.9) |

| Antimalarials, n (%) | 153 (50.8) | 67 (12.7) |

| Sulfasalazine, n (%) | 14 (4.7) | 24 (4.6) |

| Leflunomide, n (%) | 12 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Other DMARDs, n (%) | 5 (1.7) | 7 (1.3) |

| Any DMARD, n (%) | 271 (90) | 114 (21.7) |

| Biologics | 30 (10) | 7 (1.3) |

*Data available on 293 participants.

†Data available on 277 participants.

DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Development of the algorithm

Combining the variables of progressively increasing sensitivity (table 2), we developed a final four-step algorithm that identifies clinically diagnosed RA cases with a sensitivity of 96.35 (95% CI 93.56 to 98.16) and a specificity of 90.30 (95% CI 87.45 to 92.70; table 3).

Table 2.

Empirical values of sensitivity and specificity of candidate items to be included in the algorithm in the first rheumatological sample

| Variable | Cases (N=301) |

Controls (N=526) |

Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | + | − | |||

| RA certification by rheumatologist | 232 | 69 | 19 | 507 | 77.08 (71.91 to 81.70) | 96.39 (94.42 to 97.81) |

| Absence of certification for other autoimmune diseases* | 294 | 7 | 449 | 77 | 97.67 (95.27 to 99.06) | 14.64 (11.73 to 17.95) |

| ICD9-CM code 714 in HDF | 57 | 244 | 2 | 524 | 18.94 (14.67 to 23.83) | 99.62 (98.63 to 99.95) |

| Methotrexate | 182 | 119 | 31 | 495 | 60.47 (54.69 to 66.03) | 94.11 (91.74 to 95.96) |

| Antimalarials | 153 | 148 | 67 | 459 | 50.83 (45.03 to 56.61) | 87.26 (84.11 to 89.99) |

| Sulfasalazine | 14 | 287 | 24 | 502 | 4.65 (2.57 to 7.68) | 95.44 (93.29 to 97.06) |

| Leflunomide | 12 | 289 | 0 | 526 | 3.99 (2.08 to 6.86) | 100 (99.30 to 100) |

| Azathioprine | 1 | 300 | 4 | 522 | 0.33 (0.01 to 1.84) | 99.24 (98.06 to 99.79) |

| Cyclosporine | 4 | 297 | 3 | 523 | 1.33 (0.36 to 3.37) | 99.43 (98.34 to 99.88) |

| Antitumour necrosis factor α | 29 | 272 | 5 | 521 | 9.63 (6.55 to 13.54) | 99.05 (97.80 to 99.69) |

| Abatacept | 4 | 297 | 0 | 526 | 1.33 (0.36 to 3.37) | 100 (99.30 to 100) |

| Rituximab | 0 | 301 | 2 | 524 | 0 | 99.62 (98.63 to 99.95) |

| RA certification by rheumatologist+ICD9 code 714 in HDF | 41 | 260 | 1 | 525 | 13.62 (9.96 to 18.02) | 99.81 (98.95 to 100) |

| RA certification by rheumatologist+any DMARD | 211 | 90 | 14 | 512 | 70.10 (64.58 to 75.22) | 97.34 (95.57 to 98.54) |

| RA certification by rheumatologist+ICD9 code 714 in HDF+any DMARD | 38 | 263 | 1 | 525 | 12.62 (9.09 to 16.91) | 99.81 (98.95 to 100) |

*Ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis, connective tissue diseases, systemic vasculitis, inflammatory bowel diseases.

DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; ICD9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; HDF, hospital discharge form; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Table 3.

Accuracy of the algorithm in the training sample by step

| Step | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1: RA certification by rheumatologist OR ICD9-CM code 714 in HDF OR leflunomide OR tocilizumab OR abatacept OR gold salts | 82.39 (77.61 to 86.52) | 96.20 (94.19 to 97.66) |

| Step 2: Step 1 OR (methotrexate AND antimalarials AND no certification for other autoimmune diseases) | 85.38 (80.88 to 89.17) | 95.63 (93.51 to 97.21) |

| Step 3: Step 2 OR (glucocorticoids ≥3 prescriptions AND antimalarials AND no certification for other autoimmune diseases) | 91.36 (87.60 to 94.28) | 92.21 (89.57 to 94.35) |

| Step 4: Step 3 OR (methotrexate ≥3 prescriptions AND no certification for other autoimmune diseases)* | 96.35 (93.56 to 98.16) | 90.30 (87.45 to 92.70) |

*The final algorithm used in the analysis.

ICD9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; HDF, hospital discharge form; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Bootstrap procedure confirmed the robustness of the estimates in the training set (table 4).

Table 4.

Accuracy of the algorithm in the validation samples

| Training set— Rheumatological sample* |

Validating set— Rheumatological sample |

Validating set— General population |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | 96.32 (96.25 to 96.38) | 93.75 (79.19 to 99.23) | 92.50 (79.61 to 98.43) |

| Specificity (95% CI) | 90.33 (90.24 to 90.41) | 90.54 (81.48 to 96.11) | 99.77 (99.61 to 99.87) |

| PPV (95% CI) | 85.04 (80.81 to 88.66) | 81.08 (64.84 to 92.04) | 72.55 (58.26 to 84.11) |

| NPV (95% CI) | 97.74 (95.99 to 98.86) | 97.10 (89.92 to 99.65) | 99.95 (99.85 to 99.99) |

*Bootstrap estimates.

NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

More flexible methods tested in sensitivity analyses confirmed similar accuracy: logistic penalised models with multiple interaction terms showed a sensitivity of 94.35 (95% CI 91.36 to 96.68) and a specificity of 92.59 (95% CI 90.11 to 94.68); classification trees did not identify alternative pathways capable of significantly improving accuracy for the classification of cases.

Validation of the algorithm

The first external validation was performed in 106 out of 138 patients, in which record linkage was successful and sufficient clinical data available. This sample included 32 cases (30.2%) with a median age of 62.5 years (IQR 53.5–73.5) and a male:female (M:F) ratio of 1:2; 30 (93.8%) cases were treated with at least one DMARD. In the sample of controls, the median age was 57 years (IQR 51–74). The second validation set included 6087 participants (40 cases of RA and 6047 controls), with a median age of 70.5 years (IQR 57–78) with a M:F ratio of 1:3 in cases, and median age of 45 years (IQR 35–59) and M:F ratio of 1:1 in controls. In total, 27/40 (67.5%) cases were treated with at least one DMARD.

The first external validation showed highly consistent results compared with the training set (table 4). Accuracy measures in the general population sample showed a substantial increase in specificity (99.8; 95% CI 99.6 to 99.9) and decrease in PPV (72.5; 95% CI 58.3 to 84.1).

PPVs over 80% were achievable both in rheumatological samples (85.04 (80.81 to 88.66) and 81.08 (64.84 to 92.04) in training and first validating set, respectively) and in general population restricting the algorithm to DMARD users (PPV 85.7%; 95% CI 63.7% to 96.9%).

Estimation of disease prevalence

Applying the four-step algorithm to the population of the Lombardy region, a crude prevalence of 0.52% (0.30% for males and 0.73% for females) was obtained, with a M:F ratio of 1:3 and a peak of prevalence between 72 and 75 years for females, and between 75 and 78 years for males.

Adjusting for the estimated misclassification, prevalence fell to 0.31% (95% CI 0.18% to 0.45%) using Gladen and Rogan's method (in equation 1: crude prevalence=0.52%, sensibility=92.5%, specificity=99.77%) and to 0.37% (95% CI 0.26% to 0.48%), using Joseph's method with a plausible range of values included between 0.2% and 0.7%.

Discussion

This study supports the overall validity of the administrative databases of the Italian NHS of the Lombardy region in the identification of patients with RA.

Previous studies showed the validity of AHD-based algorithms to identify cases of RA, with sensitivity and specificity ranging from 56% to 100% and from 55% to 97%.15 The accuracy achieved in our study is highly consistent with those obtained by studies following similar methodology. In particular, Widdifield and colleagues recently developed a set of classification algorithms for RA using AHD in Ontario, Canada. These algorithms—derived in a randomly selected rheumatological sample with a 33% prevalence of RA—showed optimal accuracy in identifying clinical diagnoses of RA, with sensitivity/specificity up to 97/85% and PPV/NPV up to 76/98%. Although we used different items to construct our instruments in our training rheumatological sample (34% prevalence of RA), we obtained highly consistent accuracy (sensitivity/specificity 96/90% and PPV/NPV 85/98%).

Despite several algorithms being available for different AHDs in different settings, none of them have been fully validated in the general population. This leads to high PPV, of which generalisability is limited to high prevalence study samples—such as, for example, rheumatological outpatient samples—where the prevalence of RA may be higher than 50-fold.14 Once the algorithm in a rheumatological sample was developed, we measured the diagnostic performance of the algorithm in a general population sample. As expected, PPV significantly decreased to 72%, while NPV increased over 99%. Only alternative algorithms restricted to DMARD users and to rheumatology samples were associated with PPV higher than 80%. Different algorithms with different operative characteristics may be suitable for studies with different purposes: high sensitivity for impact studies and high specificity for cohort studies.14

Beyond the usefulness of misclassification data to drive decision on the criterion to apply in selecting cohort of patients, sensitivity and specificity estimates are useful to adjust occurrence measures at population level.31 This is the first study taking into account empirical misclassification in the adjustment of prevalence estimates of RA. In order to obtain unbiased estimates of prevalence, we applied a first method that arithmetically adjusts the crude estimates, taking into account the false-positive and false-negative rates.31 A more complex method that incorporates both a priori available information about the RA prevalence in Italy and empirical misclassification was also tested in order to improve the estimation based on the current knowledge.25 Regardless of the method applied, prevalence estimates ranging from 0.31% to 0.37% are consistent with those expected on the basis of the literature for Italy,26–29 providing further validation to the developed tool. Using Joseph's method with a larger range of plausible values (0.2–1%), we obtained an estimated prevalence of 0.36%.

In the design of this study we tried to limit major bias of diagnostic studies and to ensure external validity of the results.15 17 18

Study samples were randomly selected, in order to limit selection bias and to represent the entire spectrum of disease severity. To avoid observation bias due to differential misclassification, an independent investigator—who was unaware of the items included in the algorithm and of the participant classification—validated clinical diagnoses. AHD data suitable to be included in a diagnostic algorithm were identified through a literature-informed consensus process. We included this first step to avoid a completely data-driven algorithm, which could have overestimated the accuracy in the development sample. Only items from the domain of diagnostic codes and drug utilisation were deemed to be relevant, as assumed in most previous algorithms.

The robustness of our findings was also confirmed by the bootstrap procedure and by the exploration of other possible combinations of the candidate items using different statistical methods. These alternative methods achieved similar accuracy, though never significantly better than the multistep algorithm, confirming the internal validity of the results.

The generalisability of the results was evaluated by different external validations, carried out using different healthcare levels, investigators, temporal ranges and study designs.21

This study has several limitations. Cross-sectional diagnostic ‘case–control’ studies tend to overestimate diagnostic accuracy.19 However, accuracy was still satisfactory even when a cross-sectional diagnostic ‘cohort’ design was applied in a similar prevalence sample. Beyond the higher prevalence of RA in the training and the first validation set, patients drawn from rheumatology samples may include patients with more severe disease and different sociodemographic characteristics. However, the algorithm still performed well with a similar sensitivity in the general population, where the entire spectrum of the disease is represented. Furthermore, drug prescriptions of elderly patients who are hospitalised in retirement homes are not tracked by the AHD, leading to a substantial underestimation of the prevalence of the disease. Another possible source of bias is linked to the choice of the reference standard. Despite the majority of studies applying this type of case definition, clinical diagnosis is less reliable than classification criteria. However, classification criteria are developed to increase specificity in order to include patients in clinical trials and not for epidemiological purposes.32 We only adopted classification criteria22 to validate unclear diagnoses. This might have introduced a verification bias in our study, slightly increasing the specificity of the algorithms. Differential misclassification may take place based on disease duration, since the probability to have diagnostic codes and DMARD prescription may increase with disease duration, leading to under-representation of incident RA.

In conclusion, this study shows the accuracy of administrative data algorithms for identifying patients with RA in rheumatology clinics and also in the general population in Italy. This study also supports the usefulness of misclassification data to adjust estimates and to drive the decision of the appropriate algorithm to adopt based on the study objectives. Beyond the content of the applied classification criterion, validation data are useful to select homogeneous cohorts of patients with RA across countries and healthcare systems, making feasible the implementation of surveillance systems aiming to improve care of patients with RA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of the entire clinical staff, including the rheumatologists of the clinical centres, for their former data collection and for making available their registers of patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: CAS, AZ, MAC, GiCo, GM and CM planned the study. CC, MC, GiCa and SM collected the data. GrCa, FN and AA analysed the data. GrCa wrote the first draft, and all the authors critically revised and approved the final manuscript. GM was involved in obtaining of funding.

Funding: The RECORD study is funded by the Italian Society for Rheumatology (SIR) as part of the Epidemiology Unit development programme.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo Foundation of Pavia.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Woolf AD, Pfleger B. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ 2003;81:646–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolf AD, Vos T, March L. How to measure the impact of musculoskeletal conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010;24:723–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SY, Solomon DH. Use of administrative claims data for comparative effectiveness research of rheumatoid arthritis treatments. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13:129 10.1186/ar3472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corrao G, Cesana G, Merlino L. Pharmacoepidemiological research and the linking of electronic healthcare databases available in the Italian region of Lombardy. Bio Med Stat Clin Epidemiol 2008;2:117–25. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scotti L, Arfè A, Zambon A et al. . Cost-effectiveness of enhancing adherence with oral bisphosphonates treatment in osteoporotic women: an empirical approach based on healthcare utilisation databases. BMJ Open 2014;4:e003758 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabriel SE. The sensitivity and specificity of computerized databases for the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37:821–3. 10.1002/art.1780370607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz JN, Barrett J, Liang MH et al. . Sensitivity and positive predictive value of Medicare Part B physician claims for rheumatologic diagnoses and procedures. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1594–600. 10.1002/art.1780400908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacLean CH, Park GS, Traina SB et al. . Positive predictive value (PPV) of an administrative data-based algorithm for the identification of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:1–520. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Losina E, Barrett J, Baron JA et al. . Accuracy of Medicare claims data for rheumatologic diagnoses in total hip replacement recipients. J Clin Epidemiol 2003;56:515–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh JA, Holmgren AR, Noorbaloochi S. Accuracy of Veterans Administration databases for a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2004;51:952–7. 10.1002/art.20827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pedersen M, Klarlund M, Jacobsen S et al. . Validity of rheumatoid arthritis diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry. Eur J Epidemiol 2004;19:1097–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas SL, Edwards CJ, Smeeth L et al. . How accurate are diagnoses for rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis in the general practice research database? Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:1314–21. 10.1002/art.24015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SY, Servi A, Polinski JM et al. . Validation of rheumatoid arthritis diagnoses in health care utilization data. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13:R32 10.1186/ar3260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Widdifield J, Bernatsky S, Paterson JM et al. . Accuracy of Canadian health administrative databases in identifying patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a validation study using the medical records of rheumatologists. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:1582–91. 10.1002/acr.22031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Widdifield J, Labrecque J, Lix L et al. . Systematic review and critical appraisal of validation studies to identify rheumatic diseases in health administrative databases. Arthritis Care Res 2013;65:1490–503. 10.1002/acr.21993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung CP, Rohan P, Krishnaswami S et al. . A systematic review of validated methods for identifying patients with rheumatoid arthritis using administrative or claims data. Vaccine 2013;31(Supplement 10):K41–61. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.03.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benchimol EI, Manuel DG, To T et al. . Development and use of reporting guidelines for assessing the quality of validation studies of health administrative data. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:821–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE et al. . The STARD Statement for Reporting Studies of Diagnostic Accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:W1–12. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00012-w1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biesheuvel CJ, Vergouwe Y, Oudega R et al. . Advantages of the nested case-control design in diagnostic research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:48 10.1186/1471-2288-8-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinberg DM, Fine J, Chappell R. Sample size for positive and negative predictive value in diagnostic research using case-control designs. Biostatistics 2009;10:94–105. 10.1093/biostatistics/kxn018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steyerberg EW. Clinical prediction models—A practical approach to development, validation, and updating. New York: Springer, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacGregor AJ, Bamber S, Silman AJ. A comparison of the performance of different methods of disease classification for rheumatoid arthritis. Results of an analysis from a nationwide twin study. J Rheumatol 1994;21:1420–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng B, Aslam F, Petersen NJ et al. . Identification of rheumatoid arthritis patients using an administrative database: a Veterans Affairs study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:1490–6. 10.1002/acr.21736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogan WJ, Gladen B. Estimating prevalence from the results of a screening test. Am J Epidemiol 1978;107:71–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joseph L, Gyorkos TW, Coupal L. Bayesian estimation of disease prevalence and the parameters of diagnostic tests in the absence of a gold standard. Am J Epidemiol 1995;141:263–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cimmino MA, Parisi M, Moggiana G et al. . Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in Italy: the Chiavari Study. Ann Rheum Dis 1998;57:315–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salaffi F, De AR, Grassi W. Prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions in an Italian population sample: results of a regional community-based study. I. The MAPPING study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2005;23:819–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marotto D, Nieddu ME, Cossu A et al. . [Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in North Sardinia: the Tempio Pausania's study]. Reumatismo 2005;57:273–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Della Rossa A, Neri R, Talarico R et al. . Diagnosis and referral of rheumatoid arthritis by primary care physician: results of a pilot study on the city of Pisa, Italy. Clin Rheumatol 2010;29:71–81. 10.1007/s10067-009-1285-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lunn DJ, Thomas A, Best N et al. . WinBUGS—a Bayesian modelling framework: concepts, structure, and extensibility. Stat Comput 2000;10:325–37. 10.1023/A:1008929526011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gladen B, Rogan WJ. Misclassification and the design of environmental studies. Am J Epidemiol 1979;109:607–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakellariou G, Scire CA, Zambon A et al. . Performance of the 2010 classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review and a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e56528 10.1371/journal.pone.0056528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.