Abstract

Introduction

Non-pharmacological therapies for common chronic medical conditions in older patients are underused in clinical practice. We propose a protocol for the assessment of the evidence of non-pharmacological interventions to prevent or treat relevant outcomes in several prevalent geriatric conditions in order to provide recommendations.

Methods and analysis

The conditions of interest for which the evidence about efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions will be searched include delirium, falls, pressure sores, urinary incontinence, dementia, heart failure, orthostatic hypotension, sarcopaenia and stroke. For each condition, the following steps will be undertaken: (A) prioritising clinical questions; (B) retrieving the evidence (MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library, CINAHL and PsychINFO will be searched to identify systematic reviews); (C) assessing the methodological quality of the evidence (risk of bias according to the Cochrane method will be applied to the primary studies retrieved from the systematic reviews); (D) developing recommendations based on the evidence (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) items—risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness and publication bias—will be used to rate the overall evidence and develop recommendations).

Dissemination

For each target condition, at least one systematic overview concerning the evidence of non-pharmacological interventions will be produced and published in peer-reviewed journals.

Keywords: non-pharmacological interventions, systematic overview, GRADE method

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strength of the Optimal Evidence-Based Non-drug Therapies in Older People (ONTOP) project is its extensive, comprehensive systematic overview of reviews concerning non-pharmacological interventions for chronic geriatric conditions as well as the provision of a Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach-based recommendation of the evidence of non-pharmacological interventions.

A limitation of the ONTOP recommendations is that they are produced in isolation, that is, considering each geriatric condition in isolation, rather than in combination. In multimorbid older people with more than one geriatric condition, the recommendation of particular non-drug therapies may be more nuanced. In this sense, the ONTOP recommendations may need to be synthetised, avoiding repetitions when the same intervention is effective in different conditions or changing the recommendations, when the intervention that is useful for one condition might be contraindicated if the patient has another condition.

Introduction

The European population of older people with multiple chronic diseases (multimorbidity) is increasing steadily in parallel with the rising population of people aged ≥65 years.1 Older multimorbid people are at high risk of polypharmacy,2 inappropriate prescribing,3 4 adverse drug reactions5 and adverse drug events.6 Polypharmacy, inappropriate prescribing, adverse drug reactions and adverse drug events in turn cause excessive drug costs and excess healthcare utilisation;7 8 adverse drug reactions and adverse drug events also cause significant mortality.9 10

Drug therapy and non-drug therapies are complementary in the management of older people with multimorbidity. It is widely acknowledged that non-pharmacological therapies can be as effective and sometimes more effective than drug therapy in the treatment of several common chronic conditions.11 12 Nevertheless, there is a widespread underuse of non-drug therapies, such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech and language therapy, nutritional therapy and psychotherapy, in the treatment of chronic diseases and conditions. Optimal management of drug and non-drug therapy in older multimorbid persons usually requires specialist skills, but most doctors who treat older people do not have specialist training in Geriatric Medicine.13 14

To date, there is no widely used compendium of non-pharmacological therapies for the common chronic medical conditions of late life. This might contribute to their underuse in clinical practice. To fill this knowledge gap, we present the Optimal Evidence-Based Non-drug Therapies in Older People (ONTOP) project whose principal aims are to: (A) undertake a literature search of systematic reviews (SRs) concerning evidence-based non-pharmacological treatments of the common medical conditions affecting older people in order to identify those treatments that are firmly evidence-based, and (B) to define in bullet-point format the indications and contraindications of non-pharmacological therapies for which there is the strongest evidence base in each of the chronic conditions.

The ONTOP project is part of a large European Union funded research project called SENATOR (Software ENgine for the Assessment & optimization of drug and non-drug Therapy in Older persons; http://www.senator-project.eu/) that aims to build a software engine with the capacity to optimise non-pharmacological as well as pharmacological therapy and simultaneously minimise adverse drug reactions, inappropriate prescribing, polypharmacy and excessive cost in older patients with multimorbidity. The efficacy of SENATOR software will be tested by a randomised controlled clinical trial, starting in 2015.

Methods

The conditions that will be evaluated in the ONTOP project include delirium, falls, pressure sores, urinary incontinence, dementia, heart failure, orthostatic hypotension, sarcopaenia and stroke.

The following steps will be undertaken for each condition evaluated in the ONTOP project:

Formulating and prioritising clinical questions;

Retrieving the evidence using the SRs;

Assessing the methodological quality of the evidence;

Developing recommendations based on the evidence.

Formulating and prioritising clinical questions

For each of the aforementioned conditions, the ONTOP group will formulate and prioritise answerable clinical questions using the PICO methodology, which specifies the Patient population, the Intervention of interest, the Comparator and the Outcomes of interest.15 The outcome component will be the driver in the formulation of each clinical question and its importance should be based on clinical relevance rather than on evidence. To identify relevant outcomes, the ONTOP group will submit a list of outcomes to an international expert advisory panel of geriatricians for evaluation, discussion and rating.15 The ONTOP group will revise or add other outcomes that may be relevant for prioritising clinical questions. In a second round of consultation, the panel will rate the clinical outcomes as follows: critical (score 7–9), important but not critical (score 4–6) or low importance (1–3). Only critically important outcomes will be considered relevant to ONTOP recommendations.15

Retrieving the evidence from SRs

Inclusion criteria for SR

For each condition, to identify the abstracts of interest we will prepare search strategies in the following databases: Cochrane Database of Systematic Review, PubMed, PsychInfo and CINAHL. Appropriate search strategies for each electronic database will be developed.

In order to retrieve SRs, two criteria will be considered for further evaluation of an abstract, that is, (A) a paper generally defined as a review, and (B) the mention of any non-pharmacological intervention for the condition of interest. For abstracts derived from the Cochrane Library, only the second criterion will be applied. Guidelines will be excluded but will be considered for reference checking to identify potentially relevant SRs.

Full texts of relevant abstracts will then be obtained and screened to identify SRs of interest based on (1) the use of at least one medical literature database (eg, MEDLINE) for evidence search; (2) the inclusion of at least one primary study and (3) the use of at least one non-pharmacological intervention for prevention or treatment of the condition of interest. For papers written in a language other than English, an attempt at translation will be undertaken.

Pairs of reviewers will independently screen titles, abstracts and full texts. Disagreement will be resolved by discussion and, if necessary, by a third independent reviewer.

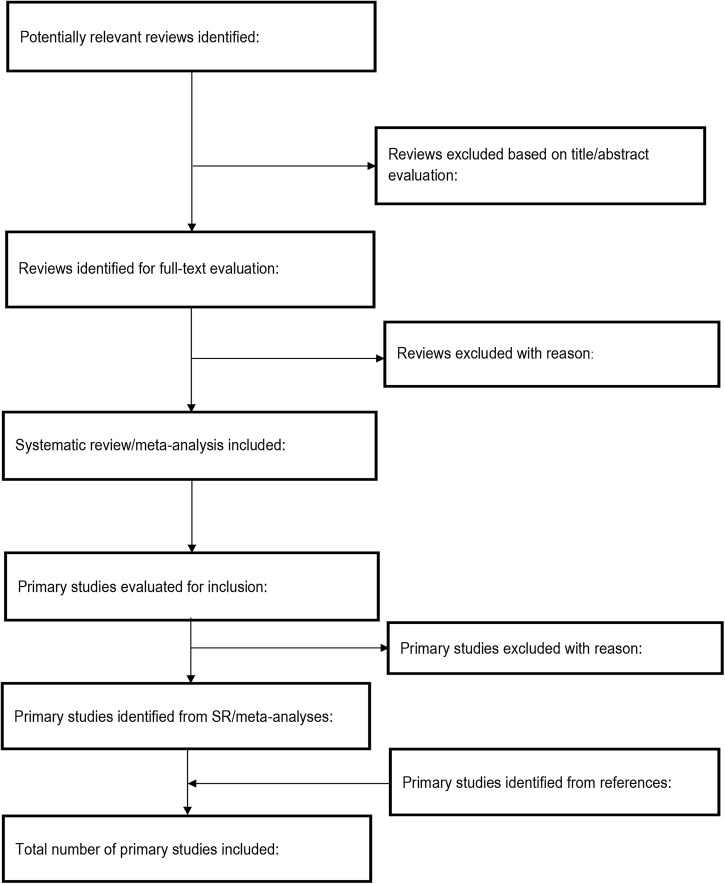

The process of published study selection will be presented in a PRISMA flow diagram (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study screening process (SR, systematic review).

We will assess the methodological quality of each SR using the AMSTAR (A Measurement Tool to Assess Reviews) instrument. AMSTAR appraises the quality of reviews using the following 11 items: duplicate study selection and data extraction, comprehensive searching of the literature, provision of a list of included and excluded studies, provision of characteristics of included studies, assessment of methodological quality of included studies, appropriate methods for combining results of studies and for assessing publication bias, and consideration of conflict of interest statement.16 Two reviewers will independently evaluate the quality of the SRs and disagreement will be resolved by consensus. Where there are multiple reviews that answer the same clinical question, the reviews with the highest score will be prioritised in the evidence retrieval and assessment.

Inclusion criteria for primary studies

From the included SRs, we will identify and consider any comparative study, either randomised or non-randomised, that investigated any non-pharmacological intervention to prevent and/or treat an ONTOP condition, as appropriate. In some conditions, for example, delirium, both prevention and treatment will be evaluated; in other conditions, for example, falls, only prevention will be considered or treatment only, as in the case of dementia. Primary studies will be excluded if they were observational studies or before-after studies with historical controls.

Data extraction and management

Pairs of reviewers will perform data extraction from primary studies independently. Data will be extracted onto study-specific data extraction forms. Information collected will include trial characteristics (year of publication, country of origin of the study, methodological quality items of the study), patients’ characteristics (number of participants, age, gender), intervention characteristics, comparator characteristics, type of outcome and outcome measures.

Measures of treatment effect

For binary outcome measures, we will use risk ratios or ORs along with their 95% CIs. For continuous outcome measures, mean difference with 95% CI will be used to estimate the summary effect; standardised mean difference will be used when data are measured on different scales.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We will assess heterogeneity according to the approach described in Section 9.5 of the Cochrane Handbook.17 Where a meta-analysis is possible with at least two studies, we will use the χ2 test and I2 statistic to assess heterogeneity. We will consider heterogeneity to be statistically significant if the p value is less than 0.1. The Cochrane Handbook guide to the interpretation of the I2 statistic will be used: 0–30% might not be important, 30–60% may represent moderate heterogeneity, 50–75% may represent substantial heterogeneity, and 75–100% represents considerable heterogeneity.

Data synthesis

We will carry out data synthesis using Review Manager software according to the Cochrane Collaboration statistical guidelines (RevMan 2014). As we expect some level of heterogeneity between studies due to the diversity of the non-pharmacological interventions, a random-effects model will be used as a primary method of meta-analysis.

Assessing the methodological quality of the evidence

The retrieved evidence will be assessed using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach. For each clinical question, evidence profiles based on the results of the treatment effect (of a meta-analysis or a single primary study) will be prepared. The GRADE system classifies the quality of evidence into four categories: (1) high (further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of the effect), (2) moderate (further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the effect and may change the estimate), (3) low (further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate) and (4) very low (any estimate of effect is very uncertain).18

The following factors that affect this rating of quality will be considered: (1) study design and execution or risk of bias,19 (2) the consistency of results,20 (3) the directness of the evidence,21 (4) the precision of the estimate of the effect22 and (5) the likelihood of publication bias.23

In case of non-randomised studies, the following three factors that may lead to upgrading the quality of evidence will be considered: (1) a strong or very strong association, (2) a dose–effect relationship, and (3) all plausible confounding may be working to reduce the demonstrated effect or increase the effect if no effect was observed.24

Risk of bias assessment

Assessment of risk of bias for all the included trials will be carried out using criteria from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. We will assess studies according to random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other potential items that can be a source of bias. We will assign risk of bias to one of three categories on the basis of the reviewer's judgement, that is, low risk, unclear risk and high risk. Given that participants and personnel cannot always be blinded due to the nature of the non-pharmacological interventions, performance bias will usually not be used for downgrading the level of evidence within the risk of bias assessment.

From evidence to recommendation

Determining the net health benefit

The ONTOP group will discuss and evaluate the net health benefit based on the anticipated balance of benefits and harms across all clinically critical outcomes. For each clinical question, a Summary of Findings (SoF) table will be produced taking into account the gathered evidence and the quality of the evidence. The SoF will be used to move from evidence to recommendations and to ensure that the ONTOP group uniformly considered the quality of the evidence, the certainty about the balance of benefits versus harms, the similarity in patients’ values and preferences and the costs of an intervention compared with the available alternatives.25

The overall quality of the evidence will be determined by the lowest quality of evidence for each of the critical outcomes.26

The ONTOP group will not perform retrieval and formal ratings of the quality of economic evidence. Any economic consideration will be based on available guidelines.

Grading the strength of a recommendation

The strength of a recommendation will be categorised as strong or weak. It will be determined by the following factors: the quality of evidence, the balance between desirable effects and undesirable ones, the values and preferences, and the resources and costs. The strength of recommendation will be considered strong when the ONTOP group is confident that the desirable effects of adherence to the recommendation outweigh the undesirable effects. High or moderate quality of evidence supports strong recommendations when this is also supported by other considerations such as the baseline risk of the population of interest, availability of the service and accessibility to care and costs.

The strength of recommendation will be considered weak when the balance of benefit and harm is uncertain (quality of evidence is low or very low), or when values and preferences are uncertain or when much higher costs are envisaged.27

Discussion

Non-pharmacological interventions in older people can be just as important as pharmacological therapies to treat chronic conditions. For instance, in dementia, psychotropic medications are used to reduce the frequency and severity of behavioural symptoms, but they provide modest symptom control28 and there are several indications of frequent and important adverse effects.28 Non-pharmacological interventions might provide a valuable alternative to treat behavioural disturbances, but they are potentially underused in clinical practice.29

The ONTOP project will provide a number of advantages to researchers, clinicians and guideline developers.

First, clinicians and healthcare providers currently often suffer from an information overload. SRs are considered as a tool that provide evidence synthesis covering almost all areas in medicine and healthcare. However, the number and variety of SRs is growing rapidly and there are concerns that for a single topic several SRs can often be identified.30 31 The project will perform updated systematic overviews concerning the non-pharmacological interventions to treat or prevent clinically relevant outcomes of chronic conditions affecting older people.

Second, since it is generally accepted that non-pharmacological interventions are not used sufficiently in clinical practice, there is a need to address this deficiency. One of the reasons for this situation may be that there is no complete compendium of known non-pharmacological interventions for the common geriatric conditions to be reviewed by the ONTOP group. The results from this project will provide the clinical practitioner with a comprehensive list of evidence-based non-pharmacological interventions.

Third, the evidence systematically retrieved from the medical literature will be evaluated using the GRADE method, which provides a systematic and transparent framework for prioritising clinical questions and determining the outcomes of interest, summarising the evidence that addresses a question, and moving from the evidence to a treatment recommendation or decision.

Potential problems and solutions

Currently, there are sufficient numbers of SRs being published in the medical literature. It is estimated that there are 11 reviews and 75 trials being published every day.32 We opted to look for the evidence based on SRs, as most of the interventions are covered by SRs. However, when the evidence from the SRs is limited, we will change our search to primary studies by performing a standard SR. Conversely, we expect to retrieve a considerable number of SRs in some conditions such as dementia. In this case, we will limit the search period to the last 5 years. Where SRs are not updated, we will perform basic SRs.

Dissemination: For each target disease or condition, a systematic overview concerning the evidence of non-pharmacological interventions will be produced and published in peer-reviewed journals.

Current status of the ONTOP project: The project started in October 2012 and is due to be completed in October 2017. The search strategies and data collection regarding the evidence for the following geriatric conditions: delirium, dementia, urinary incontinence, falls and pressure ulcers has been undertaken.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Roy Soiza at @AbdnGeriatrics

Acknowledgements: The authors acknowledge the contribution of the following Colleagues who are actively involved in the SENATOR—ONTOP project: Giuseppina Dell'Aquila, Isabel Lozano-Montoya, Joseph M Rimland, Fabiana Mirella Trotta and Manuel Velez. They thank the following panel members who agreed to participate in the Delphi process to identify relevant outcomes for the conditions of interest: Hubert Blain, Karen Andersen Ranberg, Regina Roller-Wirnsberger, Fabio Salvi, Andrea Corsonello, Adalsteinn Gudmundsson, Akner Gunnar and Mirko Petrovic.

Contributors: IA, AC-J, RLS, DO and AC conceived, drafted and approved the final version of the protocol.

Funding: This work was supported by the European Union Seventh Framework program (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement n° 305930 (SENATOR).

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

Data sharing statement: The findings of this systematic review will be disseminated via peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations. All the data will be available.

References

- 1.Menotti A, Mulder I, Nissinen A et al. . Prevalence of morbidity and multimorbidity in elderly male populations and their impact on 10-year all-cause mortality: the FINE study (Finland, Italy, Netherlands, Elderly). J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54:680–6. 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00368-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sergi G, De Rui M, Sarti S et al. . Polypharmacy in the elderly: can comprehensive geriatric assessment reduce inappropriate medication use? Drugs Aging 2011;28:509–18. 10.2165/11592010-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallagher P, Lang PO, Cherubini A et al. . Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in an acutely ill population of older patients admitted to six European hospitals. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2011;67:1175–88. 10.1007/s00228-011-1061-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallagher P, O'Mahony D. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ potentially inappropriate Prescriptions): application to acutely ill elderly patients and comparison with Beers’ criteria. Age Ageing 2008;37:673–9. 10.1093/ageing/afn197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkin PA, Veitch PC, Veitch EM et al. . The epidemiology of serious adverse drug reactions among the elderly. Drugs Aging 1999;14:141–52. 10.2165/00002512-199914020-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dequito AB, Mol PG, van Doormaal JE et al. . Preventable and non-preventable adverse drug events in hospitalized patients: a prospective chart review in the Netherlands. Drug Saf 2011;34:1089–100. 10.2165/11592030-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leendertse AJ, Van Den Bemt PM, Poolman JB et al. . Preventable hospital admissions related to medication (HARM): cost analysis of the HARM study. Value Health 2011;14:34–40. 10.1016/j.jval.2010.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rottenkolber D, Schmiedl S, Rottenkolber M et al. . Adverse drug reactions in Germany: direct costs of internal medicine hospitalizations. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20:626–34. 10.1002/pds.2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N et al. . Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2002–12. 10.1056/NEJMsa1103053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilton H, Gallagher P, Ryan C et al. . Potentially inappropriate medications defined by STOPP criteria and the risk of adverse drug events in older hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1013–19. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naci H, Ioannidis JP. Comparative effectiveness of exercise and drug interventions on mortality outcomes: metaepidemiological study. BMJ 2013;347:f5577 10.1136/bmj.f5577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor RS, Sagar VA, Davies EJ et al. . Exercise-based rehabilitation for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;4:CD003331 10.1002/14651858.CD003331.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirth VA, Eleazer GP, Dever-Bumba M. A step toward solving the geriatrician shortage. Am J Med 2008;121:247–51. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eleazer GP, Brummel-Smith K. Commentary: aging America: meeting the needs of older Americans and the crisis in geriatrics. Acad Med 2009;84:542–4. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819f8da9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R et al. . GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:395–400. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA et al. . Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007;7:10 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA et al. . GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:383–94. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist G et al. . GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence—study limitations (risk of bias). J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:407–15. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R et al. . GRADE guidelines: 7. Rating the quality of evidence—inconsistency. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1294–302. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R et al. . GRADE guidelines: 8. Rating the quality of evidence—indirectness. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1303–10. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R et al. . GRADE guidelines 6. Rating the quality of evidence—imprecision. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1283–93. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Montori V et al. . GRADE guidelines: 5. Rating the quality of evidence—publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1277–82. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Sultan S et al. . GRADE guidelines: 9. Rating up the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1311–16. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brunetti M, Shemilt I, Pregno S et al. . GRADE guidelines: 10. Considering resource use and rating the quality of economic evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:140–50. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Sultan S et al. . GRADE guidelines: 11. Making an overall rating of confidence in effect estimates for a single outcome and for all outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:151–7. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrews JC, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD et al. . GRADE guidelines: 15. Going from evidence to recommendation—determinants of a recommendation's direction and strength. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:726–35. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Yu JT, Wang HF et al. . Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015;86:101–9. 10.1136/jnnp-2014-308112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradford A, Shrestha S, Snow AL et al. . Managing pain to prevent aggression in people with dementia: a nonpharmacologic intervention. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2012; 27:41–7. 10.1177/1533317512439795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM et al. . Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:15 10.1186/1471-2288-11-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM et al. . A systematic review and quality assessment of systematic reviews of randomised trials of interventions for preventing and treating preterm birth. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2009;142:3–11. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bastian H, Glasziou P, Chalmers I. Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000326 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.