Abstract

The bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a significant cause of acute nosocomial infections as well as chronic respiratory infections in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF). Recent reports of the intercontinental spread of a CF-specific epidemic strain, combined with high intrinsic levels of antibiotic resistance, have made this opportunistic pathogen an important public health concern. Strain-specific differences correlate with variation in clinical outcomes of infected CF patients, increasing the urgency to understand the evolutionary origin of genetic factors conferring important phenotypes that enable infection, virulence, or resistance. Here, we describe the genome-wide patterns of homologous and nonhomologous recombination in P. aeruginosa, and the extent to which the genomes are affected by these diversity-generating processes. Based on whole-genome sequence data from 32 clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa, we examined the rate and distribution of recombination along the genome, and its effect on the reconstruction of phylogenetic relationships. Multiple lines of evidence suggested that recombination was common and usually involves short stretches of DNA (200–300 bp). Although mutation was the main source of nucleotide diversity, the import of polymorphisms by homologous recombination contributed nearly as much. We also identified the genomic regions with frequent recombination, and the specific sequences of recombinant origin within epidemic strains. The functional characteristics of the genes contained therein were examined for potential associations with a pathogenic lifestyle or adaptation to the CF lung environment. A common link between many of the high-recombination genes was their functional affiliation with the cell wall, suggesting that the products of recombination may be maintained by selection for variation in cell-surface molecules that allows for evasion of the host immune system.

Keywords: homologous recombination, horizontal transfer, population genomics, comparative genomics, epidemic, adaptation

Introduction

In microbes that reproduce asexually via mitosis, mutation is a primary source of new genetic variation for adaptive evolution. However, it is well established that nonmeiotic recombination can and often does play a major role in the evolution of many microbial species (Awadalla 2003; Didelot and Maiden 2010; He et al. 2010; Didelot et al. 2011; Snitkin et al. 2011; Joseph et al. 2012; Namouchi et al. 2012). Just how important recombination is in governing the evolutionary dynamics of bacterial species is a major focus of current research.

Understanding the evolutionary impact of recombination in microbes, and in microbial pathogens in particular, is important for three reasons. First, recombination unlinks adjacent genomic regions and allows different genes to have different evolutionary histories. This complicates the reconstruction of phylogenetic relationships and makes it difficult to identify biologically cohesive groups such as species or epidemic strains associated with an outbreak of disease. Second, our ability to identify genotype–phenotype associations relies on recombination to unlink adjacent genes in a genome, making it possible to attribute specific genes or gene clusters to a particular phenotype such as virulence or drug resistance. Third, nonhomologous recombination (also known as lateral or horizontal gene transfer) can transfer novel genomic content between genetically distinct genotypes or species that allows the recipient to acquire new phenotypes or adapt to new niches. With microbial pathogens, for example, the acquisition of foreign genomic regions can often confer increased virulence or pathogenicity (Jackson et al. 2011). Similarly, resistance to antimicrobial agents can be gained repeatedly through lateral transfer of resistance genes that are pre-existing in the population (Enright et al. 2002).

Our ability to make strong inferences about the role of recombination in governing pathogen evolution has been limited. One reason for this is simply that we have lacked, until recently, appropriate data. A comprehensive view of recombination’s effects on genomic evolution requires whole-genome sequences from multiple isolates, something that has only recently been possible on sufficiently large scales (e.g., He et al. 2010, Joseph et al. 2012, Namouchi et al. 2012). A second reason is that we lack a principled, integrated system that allows us to perform a joint evolutionary inference of homologous recombination, along with inference of the substitution process and patterns of genomic gain and loss (nonhomologous recombination). Instead, one must rely on a variety of currently available specialized tools, each with their respective advantages and limitations.

To fill these gaps in knowledge, we have studied genome-wide patterns of recombination among multiple isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an opportunistic pathogen of humans, using a range of analytical methods. We focus mainly on P. aeruginosa isolated from the infected respiratory tracts of patients with cystic fibrosis (CF). Chronic endobronchial infections are found in up to 80% of adult CF patients (Aaron et al. 2010; LiPuma 2010) and are associated with increased morbidity and mortality (Hauser et al. 2011). Independent infections can be caused by isolates with wide genetic diversity, and a number of transmissible, epidemic strains of P. aeruginosa have now been described (Armstrong et al. 2002; Winstanley et al. 2009; Aaron et al. 2010; Yang et al. 2011). Infection with an epidemic strain can confer a poorer prognosis than infection with a nonepidemic strain (Al-Aloul et al. 2004; Aaron et al. 2010), implying that strain-specific variation among resident P. aeruginosa is responsible for different clinical outcomes of CF patients.

The genetic diversity underlying strain-specific differences is believed to come, in part, from recombination among isolates in the global P. aeruginosa population. Consistent with this idea, both multilocus sequence typing (MLST) studies (Kiewitz and Tummler 2000; Curran et al. 2004; Pirnay et al. 2009; Maatallah et al. 2011; Kidd et al. 2012) and our recent comparative genomics study (Dettman et al. 2013) have found evidence that recombination is fairly common in this species. The goal of the current study was to perform more detailed analyses of genome-wide recombination in P. aeruginosa to determine how recombination contributes to genomic diversity and the role it has played during the evolution of this human pathogen.

Using whole-genome sequences from a sample of 32 clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa, we first investigate the nature and extent of recombination in the core and accessory genomes. This allows us to characterize, at a fairly coarse scale, the importance of recombination in P. aeruginosa and the effects it has had on genomic variation. We then identify the core genome regions most frequently affected by recombination, and the specific sequences of recombinant origin within epidemic strains. The functional characteristics of the genes within recombinant regions are examined for potential associations with a pathogenic lifestyle or adaptation to the CF lung environment.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources, Genome Alignment, and Phylogenies

Whole-genome sequence data for 24 P. aeruginosa isolates from Ontario, Canada were reported in our previous comparative genomics study (Dettman et al. 2013). These 24 isolates were all sampled from the chronically infected respiratory tracts of adult patients with CF. The remaining eight genomes were downloaded from public databases. Location of sampling, genome data, and accession numbers are listed in table 1. Genomes were aligned using ProgressiveMauve (Darling et al. 2010, version 2.3.1) with iterative refinement and allowing rearrangements. Default settings were used and PA14 was the reference genome. ProgressiveMauve is a multiple genome alignment heuristic that identifies locally collinear blocks (LCBs) of conserved sequence using positional homology in genome, as well as sequence homology. If an LCB contained sequences from all 32 genomes, it was classified as “core” genome. All other LCBs had sequence missing for at least one isolate so therefore were classified as “accessory” genome. Phylogenetic trees were constructed from the core genome using PhyML (Guindon et al. 2010, version 3.0; GTR+G+I model of substitution, base frequencies and proportion of invariable sites estimated by maximum likelihood (ML), 1,000 bootstrap replicates).

Table 1.

Information on the 32 Pseudomonas aeruginosa Genomes

| Isolate | City of Isolation | Source | Epidemic | GenBank Accesion | Genome State | Assembly Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JD303 | Toronto, Canada | CF patient | No | AWYU00000000 | Draft | 6,353,798 |

| JD304 | Ottawa, Canada | CF patient | LESA | AWYT00000000 | Draft | 6,439,488 |

| JD306 | Toronto, Canada | CF patient | No | AWYS00000000 | Draft | 6,647,721 |

| JD310 | Ottawa, Canada | CF patient | LESA | AWYR00000000 | Draft | 6,424,472 |

| JD312 | Kitchener, Canada | CF patient | No | AWYQ00000000 | Draft | 6,299,443 |

| JD313 | Hamilton, Canada | CF patient | ESB | AWYP00000000 | Draft | 6,348,777 |

| JD314 | Kitchener, Canada | CF patient | No | AWYO00000000 | Draft | 6,233,472 |

| JD315 | Hamilton, Canada | CF patient | LESA | AWYN00000000 | Draft | 6,406,347 |

| JD316 | Sudbury, Canada | CF patient | ESB | AWYM00000000 | Draft | 6,215,338 |

| JD317 | Toronto, Canada | CF patient | No | AWYL00000000 | Draft | 6,511,721 |

| JD318 | Hamilton, Canada | CF patient | No | AWYK00000000 | Draft | 6,230,857 |

| JD320 | Toronto, Canada | CF patient | No | AWYJ00000000 | Draft | 6,435,861 |

| JD322 | Toronto, Canada | CF patient | LESA | AWYV00000000 | Draft | 6,478,170 |

| JD323 | Hamilton, Canada | CF patient | No | AWYW00000000 | Draft | 5,996,350 |

| JD324 | Toronto, Canada | CF patient | LESA | AWYX00000000 | Draft | 6,432,592 |

| JD325 | Hamilton, Canada | CF patient | No | AWYY00000000 | Draft | 6,294,013 |

| JD326 | Hamilton, Canada | CF patient | LESA | AWYZ00000000 | Draft | 6,470,946 |

| JD328 | London, Canada | CF patient | ESB | AWZA00000000 | Draft | 6,346,874 |

| JD329 | London, Canada | CF patient | LESA | AWZB00000000 | Draft | 6,430,078 |

| JD331 | London, Canada | CF patient | ESB | AWZC00000000 | Draft | 6,345,919 |

| JD332 | Ottawa, Canada | CF patient | No | AWZD00000000 | Draft | 6,183,240 |

| JD333 | Toronto, Canada | CF patient | ESB | AWZE00000000 | Draft | 6,350,229 |

| JD334 | Sudbury, Canada | CF patient | No | AWZF00000000 | Draft | 6,730,042 |

| JD335 | Toronto, Canada | CF patient | LESA | AWZG00000000 | Draft | 6,401,946 |

| PA14 | Burn patient | No | NC_008463 | Finished | 6,537,648 | |

| LESB58 | Liverpool, England | CF patient | LESA | NC_011770 | Finished | 6,601,757 |

| PAO1 | Melbourne, Australia | Wound | No | NC_002516 | Finished | 6,264,404 |

| PACS2 | CF patient, paediatric | No | NZ_AAQW00000000 | Draft | 6,492,423 | |

| PA2192 | Boston, USA | CF patient | No | NZ_AAKW00000000 | Draft | 6,826,253 |

| PA39016 | Keratitis | No | NZ_AEEX00000000 | Draft | 6,667,333 | |

| C3719 | Manchester, England | CF patient | putative epidemic strain | NZ_AAKV00000000 | Draft | 6,146,998 |

| PAb1 | Frostbite patient | No | NZ_ABKZ00000000 | Draft | 6,078,600 |

Homologous Recombination

Homologous recombination is when nucleotide sequences are exchanged between similar or identical regions of DNA. As such, our analyses of homologous recombination were restricted to the core genome, where all isolates have homologous sequence. The program BratNextGen (Marttinen et al. 2012) was used to identify regions of the core genome that were of recombinant origin. BratNextGen divides the genome into segments, then for each segment, detects genetically distinct clusters of isolates and estimates the probabilities of recombination events. The 32 isolates were divided into six clusters based on the proportion of shared ancestry tree. Learning of recombinations was performed on the ordered, core genome alignment for 100 iterations, at which point the parameters had stabilized. The same analysis was repeated 150 times to estimate significance. Results shown here are with the significance threshold for recombination detection set to P ≤ 0.01. Analyses were repeated with significance threshold of ≤ 0.05 (data not shown, average of 6.89% of genome removed per isolate) and the results were very similar to when P ≤ 0.01 was used.

The program ClonalFrame (Didelot and Falush 2007, version 1.2) implements a Bayesian approach in which a single phylogeny is estimated for the entire genome alignment while accounting for homologous recombination. An advantage of the ClonalFrame method is that it allows mutation and recombination events to be assigned to specific branches of the phylogeny. ClonalFrame runs applied to the full core genome had the following settings: 10,000 burn-in iterations followed by 10,000 iterations with parameter samples recorded every ten iterations (posterior sample of 1001). Mutation rate (theta, θ) was calculated from the data and held constant, whereas the tree topology, branch lengths, recombination tract length (delta, δ), rate of new polymorphism introduced by recombination (nu, υ), and recombination rate (rho, ρ) were free to vary.

Mutation and recombination events are assigned to specific branches of the consensus phylogeny by the ClonalFrame method. For the calculation of the number of recombination events affecting a site, the ClonalFrame output file (from the run with the highest log-likelihood) was parsed to extract the posterior probability of recombination at each reference and polymorphic site along each branch of the consensus phylogeny. If the posterior probability of recombination was ≥ 0.90, it was deemed a recombination event. For each site, the number of recombination events was summed across all branches of the tree. To visualize trends, moving averages (500 sites per window with a step size of 250 sites, or 20 sites per window with a step size of 10 sites) of the number recombination events were calculated along the core alignment.

Regions with consecutive reference sites that experienced eight or more recombination events were identified. The threshold of eight or greater was somewhat arbitrary and was chosen simply to limit our analyses to the top approximately 50 regions with highest recombination. Edges of the high recombination region were set to sites where the number of recombination events dropped down to 2. Sequences from these high-recombination stretches of genome (n = 44) were extracted and BLAST searched against P. aeruginosa genomes to identify affected genes. BLAST2GO (Gotz et al. 2008, version 2.5) was used for analyses of gene ontology (GO) data; however, only 28% of these high-recombination genes had GO information available. Thus, manual curation of gene function was necessary, and relied on information collected from P. aeruginosa annotations, homology searches, and structural features.

Calculation of linkage disequilibrium (LD) requires that the physical distances between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) be known, so analyses were restricted to individual LCBs. Using DnaSP (Librado and Rozas 2009, version 5.10), the correlation coefficient of haplotype frequencies (r2) was calculated for all pairs of SNPs for each of the ten longest LCBs, then pooled (293,081 pairwise comparisons). Distance-dependent decay of LD was demonstrated by the negative linear slope (P > 0.00001) for plots of r2 against distance between SNPs. To visualize the point at which LD stabilized, distance was binned at various scales and mean r2 was calculated. The same analyses were also performed with a different LD measure; the absolute value of the deviation of the observed haplotype frequency from the expected (|D′|). Here, we present the results from r2 only because the patterns and conclusions from both LD measures were very similar.

Branch-Specific Regions of Homologous Recombination

Coordinates for recombination events (posterior probability ≥ 0.90) mapped by ClonalFrame analyses to the branch subtending the Liverpool/Epidemic Strain A (LESA) clade were determined. Stretches of consecutive reference sites that had experienced recombination were isolated and sequence was extracted if the region was greater than 500 bp in length. These recombinant LESA genome regions were BLAST searched against annotated P. aeruginosa genomes to identify affected genes. GO data were available for only 16% of these genes so manual curation of functional information was again necessary. These analyses were repeated with the other epidemic strain, Epidemic Strain B (ESB). The results for LESA and ESB clades were compared to identify regions of recombinant origin (>100 bp) that were shared among both of these epidemics strains.

Population Structure

The program Structure (Falush et al. 2003, version 2.3.4) was used to infer population structure and cluster isolates into populations (under the admixture model). The data set consisted of all segregating SNPs in the core genome (n = 78,911), many of which were physically linked, so all analyses allowed for correlated allele frequencies. Runs had 10,000 burn-in iterations followed by 10,000 sampling iterations. Triplicate runs were performed with the number of populations (K) set to each value from 3 to 16, then the estimated probabilities of the data (logarithm of the marginal likelihood) were compared to determine which K value was most appropriate. Given the known problems with harmonic mean estimators of marginal likelihoods, accurately determining the number of discrete populations is difficult. In this article however, the main purpose of structure analyses was to infer mixed ancestry of isolates, so the value of K was not of prime importance.

Phylogenetic Incongruence

To visualize incongruence among data, split networks were constructed with the program SplitsTree4 (Huson and Bryant 2006, version 4.13.1) under default settings using the 137,941 polymorphic sites in the core genome. Calculations of the pairwise homoplasy index (PHI) and its significance were also performed with SplitsTree4. For a different approach, incongruence was examined by comparing the topologies of trees constructed from different regions of the genome. The core genome alignment was divided into 25 segments of 0.2 Mb in length, except the last segment which was 0.206 Mb in length. To focus on the taxa with the most incongruence, and to simplify the comparison, alignments were pruned to retain JD317 and eight isolates with the highest genetic similarity to it. Single isolates were chosen to represent named clades or strains such as LESA and ESB. For each core segment, a neighbour-joining tree was built from Kimura-2-parameter genetic distances and the topology recorded (branch lengths are not proportional in figure). Unrooted tree topologies were compared using Robinson–Foulds distances normalized over 2n−6 where n = number of taxa. A value of 1.0 therefore indicates that no partitions are shared between trees.

Accessory Genome and Genomic Flux

Sampling saturation curves for the pan-genome (core + accessory) were based on core/accessory genome sizes calculated for genome combinations of 2 < n < 32. All possible combinations were assessed at each level unless the number of possible combinations was greater than 10,000, in which case a random sample of 10,000 was taken. We isolated all unique, nonredundant accessory genome regions, filtered out those that were less than 1 kb in length, retaining a total of 1,375 accessory regions. Correlation coefficients (R2) were calculated for each pair of isolates, based on the length of sequence present for each accessory region. Each of the regions was weighted equally in correlation and distance calculation. A neighbour-joining tree was constructed from a pairwise distance ( = 1−R2) matrix to visualize the relationships based on accessory genome content.

Nonhomologous recombination is the transfer of novel DNA sequences that the recipient genome does not already contain, or the loss of existing sequence. The patterns of gain and loss of genome regions, collectively known as genomic flux, were estimated using GenoPlast (Didelot et al. 2009, version 1.0). An ultrametric ML tree constructed from the core genome was used as the reference tree. Two runs of 5,000 iterations converged on similar estimates, so means are reported. Probabilities of ancestral events were exported and used to designate gains or losses of genomic features (100 bp) using a probability threshold of ≥0.95. Proportional flux values were calculated by dividing the number of feature gains or losses by the total number of features.

Results

Homologous Recombination in the Core Genome

Core Genome Alignment

Alignment of the 32 P. aeruginosa genomes (table 1) identified 4,790 LCBs of conserved sequence. To focus on core genome regions with confident alignment and homology assessment, we retained only the 1,351 core genome blocks that were at least 1 kb in length (Dettman et al. 2013). These core blocks were concatenated and the resulting core genome alignment was 5,058,069 nt in length and contained 137,941 variable sites. Polymorphisms were distributed fairly evenly across the length of the genome, with hotspots in a small number of regions (see Dettman et al. 2013 for details). Pseudomonas aeruginosa genomes average 6.39 Mb in length so this core genome alignment represents a large proportion (79%) of the entire genome.

Rates of Homologous Recombination

Homologous recombination allows the exchange of DNA with similar or identical sequences. In bacteria, this exchange typically is nonreciprocal, with the donor sequence simply replacing the homologous sequence in the recipient genome. We used ClonalFrame (Didelot and Falush 2007) to estimate the recombination rate (ρ) and recombination tract length (δ; the number of base pairs introduced for a given recombination event). Seven independent runs converged on similar values for the main recombination parameters, as shown in table 2. Briefly, the ratio of the rates of recombination versus mutation was 0.181 (ρ/θ, range = 0.168–0.198), implying that the mutation rate is over 5-fold greater than recombination rate. Mean recombination tract length was 273 bp (δ, range = 249–322), indicating that a single recombination event could introduce multiple nucleotide polymorphisms into the genome at the same time. When this was accounted for, the ratio of probabilities that a given site in the alignment is altered through recombination versus mutation was 0.853 (r/m, range = 0.801–0.917). Although recombination occurs less frequently than mutation, its contribution to genetic diversity is nearly the same.

Table 2.

Results Summary of ClonalFrame Runs Applied to Full Core Genome Alignment

| Run | υ (95% CI) | ρ (95% CI) | δ (95% CI) | ρ/θ (95% CI) | r/m (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.019 (0.015, 0.024) | 5735.0 (4577.7, 7215.8) | 271.3 (204.9, 353.8) | 0.168 (0.134, 0.211) | 0.801 (0.630, 0.988) |

| 2 | 0.020 (0.015, 0.026) | 5887.8 (4530.5, 7362.6) | 254.1 (183.9, 346.8) | 0.172 (0.132, 0.215) | 0.806 (0.617, 0.994) |

| 3 | 0.020 (0.015, 0.026) | 6073.2 (4655.1, 8387.5) | 257.7 (188.1, 341.2) | 0.178 (0.136, 0.245) | 0.840 (0.647, 1.101) |

| 4 | 0.016 (0.013, 0.018) | 6555.2 (5265.7, 7766.2) | 322.0 (262.9, 414.6) | 0.192 (0.154, 0.227) | 0.917 (0.738, 1.092) |

| 5 | 0.018 (0.013, 0.022) | 5969.9 (4756.3, 7328.0) | 301.7 (218.6, 408.6) | 0.175 (0.139, 0.214) | 0.850 (0.670, 1.047) |

| 6 | 0.020 (0.016, 0.023) | 6342.8 (5117.9, 7497.1) | 252.8 (200.5, 310.8) | 0.186 (0.149, 0.219) | 0.859 (0.693, 1.008) |

| 7 | 0.020 (0.017, 0.022) | 6771.9 (5480.5, 8108.2) | 249.3 (209.5, 292.0) | 0.198 (0.160, 0.237) | 0.899 (0.734, 1.059) |

Note.—υ, rate of new polymorphism introduced by recombination; ρ, recombination rate; δ, recombination tract length; ρ/θ, ratio of rates at which recombination and mutation occur; r/m, ratio of probabilities that a given site is altered through recombination and mutation; CI, credible interval.

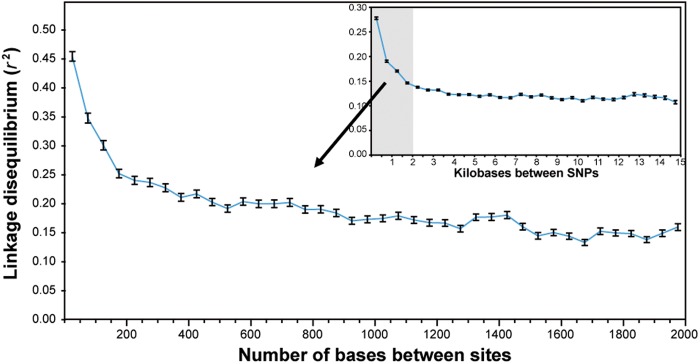

Linkage Disequilibrium

To examine the effect of recombination on the distribution of genetic variation within the core genome, we determined the patterns of LD, or the extent to which distinct polymorphic sites are nonrandomly associated. High LD, indicative of low recombination, was found for sites in close physical proximity. As distance between sites increased, LD decreased and appeared to stabilize at distance of approximately 3 kb. The most rapid drop in LD occurred within the first 200 bp (fig. 1), a length that is similar to the mean recombination tract length estimated from ClonalFrame analyses. This pattern of distance-dependent decay of LD lends further support to the idea that recombination is common and usually involves short genomic regions.

Fig. 1.—

Distance-dependent decay of LD. The main graph shows a high-resolution view of the distance range that is shaded in the inset graph.

Core Genome Phylogeny

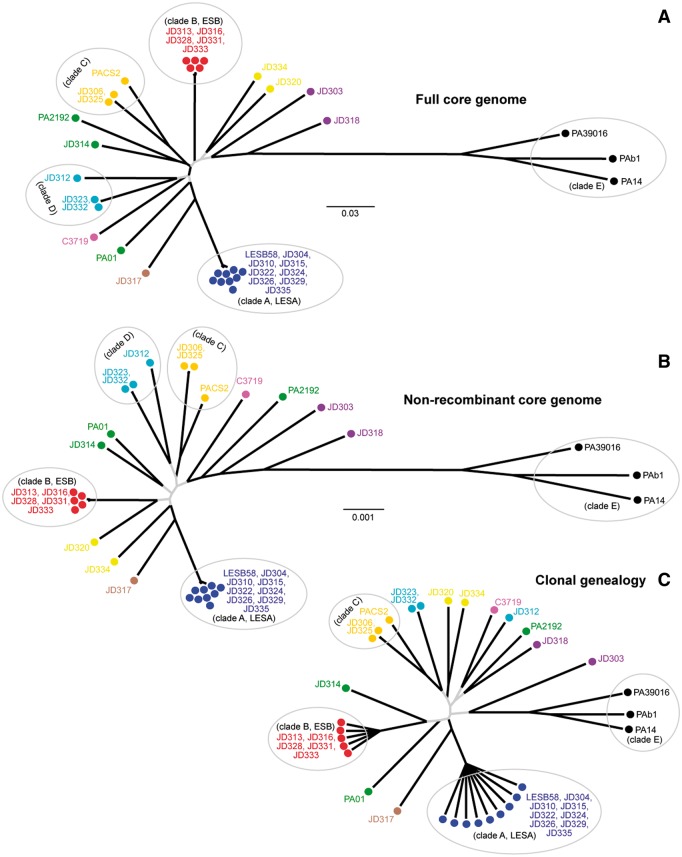

The ML phylogeny built from the core genome is shown in figure 2A. For the sake of discussion, we have named the five main clades, A through E. Note that Clades A and B correspond to LESA and ESB, respectively. The ingroup phylogeny has a star-like shape and contains little information on the evolutionary relationships among the main clades.

Fig. 2.—

Comparison of phylogenetic trees constructed from different core genome data sets. (A) ML phylogeny of full core genome which contained 137,941 SNPs. Black branches had greater than 70% bootstrap support whereas gray branches had less than 70% bootstrap support. (B) ML phylogeny of nonrecombinant regions of core genome, which contained 124,926 SNPs. Branch shading indicates branch support as in A. (C) Majority-rule consensus tree from the ClonalFrame run with the highest mean likelihood. Black branches were present in the majority-rule consensus tree of all seven independent ClonalFrame runs combined, whereas gray branches were not.

Phylogenetic Incongruence

Incompatible phylogenetic signals arising from recombination and genetic exchange were visualized by a split network constructed from all SNPs in the core genome (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online). A PHI test found that inferred recombination was significant (P < 0.01). Evidence of phylogenetic incongruence, indicated by splits in the network, was most common between basal ingroup isolates and the outgroup Clade E.

Genetic Population Structure

We used the program Structure (Falush et al. 2003) to analyze the population structure and the distribution of segregating SNPs shared among core genomes. Comparisons of analyses with the number of populations (K) set from 3 to 16 indicated that K = 7 was most appropriate. Division into seven clusters was also biologically sensible given the phylogenetic structure of the sample (fig. 2A). Similar to the phylogenetic analyses, obvious groups like Clades A, B, and E were clearly differentiated (supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online) but most other isolates showed mixed ancestry, consistent with a history of recombination.

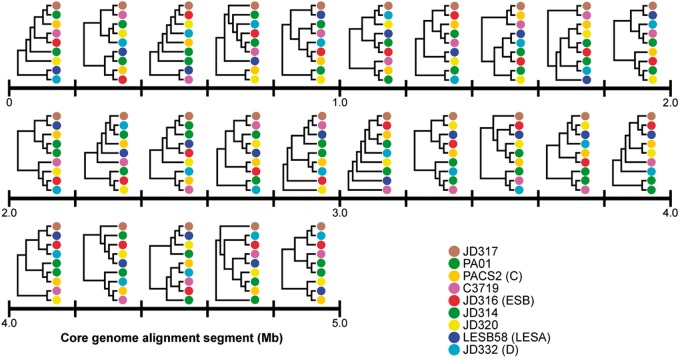

Genomic Mosaicism

The patterns of SNPs shared through recombination were highly variable among isolates (see supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online). For example, the majority of SNPs possessed by isolates within Clades A, B, and E were unique to their respective clades, revealing little evidence for external recombination. On the other hand, some isolates appeared to have highly mixed ancestry, resulting in genomes with a mosaic structure (supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online). This interpretation was reinforced when we divided the core genome into 0.2 Mb segments and compared sequence similarity between isolates. Here, for demonstration, we focus on the relationship between isolate JD317 and LESA clade. We chose this example because JD317 showed the highest degree of genomic mosaicism and shared a most common recent ancestor with LESA, the most prevalent epidemic strain of P. aeruginosa in North America. JD317 had the highest sequence similarity with LESA for only 10 of 25 (40%) core genome segments. So although JD317 is, on average, most closely related to LESA, its core genome contains a mosaic of genomic elements that are more similar to other isolates (e.g., ESB, JD314, JD320). Mosaic genomes such as JD317 can frustrate the reconstruction of phylogenies. To illustrate this, we examined the topologies of trees constructed from each of the 0.2 Mb segments separately using JD317 and eight other isolates (fig. 3). Tree topologies differed drastically and pairs of trees shared an average of only 6% of their partitions. This example demonstrates the potential for broad-scale genomic mosaicism; detailed analyses on a gene-by-gene basis would surely reveal even more, finer-scale mosaicism of these genomes.

Fig. 3.—

Comparison of topologies of trees constructed from 0.2 Mb subsets of the core genome. Trees are placed directly above the alignment segment from which they were constructed. For the sake of comparison, all topologies are displayed with JD317 at the top. The average normalized Robinson–Foulds distance between all possible pairs of trees was 0.94.

Star-Like Phylogeny Is Robust to the Effects of Homologous Recombination

Clearly, different regions of these P. aeruginosa genomes have different histories of evolutionary descent. This type of phylogenetic conflict among partitions could be contributing to the poorly resolved, star-like tree built from the entire core genome (fig. 2A). Is the star-like tree structure the direct result of extensive phylogenetic incongruence generated by recombination, or does it accurately represent the true evolutionary histories of these strains?

To answer this question, we used two methods to generate new phylogenies that accounted for homologous recombination in the core genome. First, we identified regions of the core genome that were of recombinant origin in each genome (supplementary fig. S3, Supplementary Material online), using the program BratNextGen (Marttinen et al. 2012). For each isolate, we removed regions of recombinant origin from the core alignment, which ranged from 0.78% to 10.57% of the genome, with an average of 4.32% (SE = 0.55, supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). This recombinant-free alignment, which had 13,015 less polymorphic sites than the full alignment, was used to construct a new core phylogeny (fig. 2B). Second, we reconstructed the clonal relationships among the genomes using the program ClonalFrame, which performs Bayesian phylogenetic inference under a model that accounts for homologous recombination. The seven independent runs converged on consensus trees that differed primarily in the basal relationships among strains (fig. 2C and supplementary fig. S4, Supplementary Material online).

As shown in figure 2B and C, both methods for accounting for recombination produced tree topologies that closely resembled the star-like pattern of the original, full core genome phylogeny (fig. 2A). Note that Clades A, B, C, and E received significant support in all analyses; the basal relationships among these and the other lineages are what remains poorly resolved. So although recombination is frequent, accounting for its effects did not improve the resolution of the phylogeny. This result suggests that the trees in figure 1 accurately depict the evolutionary histories of these strains.

Nonhomologous Recombination in the Accessory Genome (Genomic Flux)

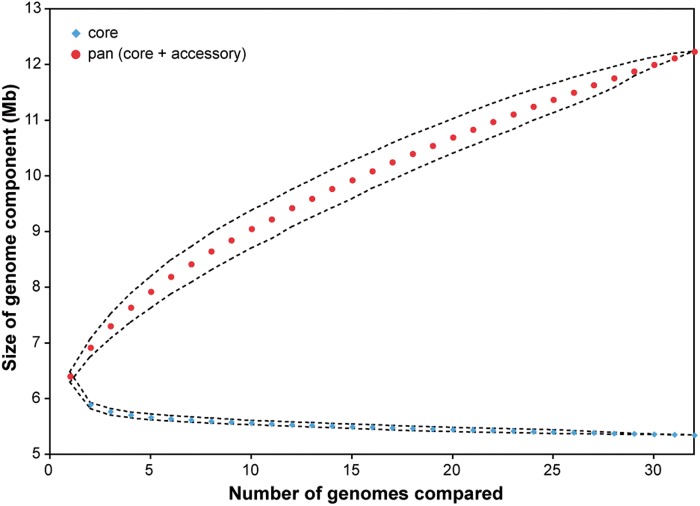

Accessory Genome Size

The size of the accessory and core genomes for different numbers and combinations of genome comparisons was calculated from the genome alignment. The size of the total genome pool, or the pan-genome (core + accessory), did not plateau in rarefaction curves (fig. 4) even though three quarters of these isolates were from a limited geographic region within Canada. The accessory genome component was responsible for the steady increase, suggesting that further sampling would likely reveal novel genes and accessory genome content in this pathogen. When all 32 genomes were compared, the amount of accessory genome possessed by each P. aeruginosa isolate ranged from 0.65 to 1.55 Mb (supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online), comprising an average of 16.4% (SE = 0.005) of each genome.

Fig. 4.—

Rarefaction curves for the size of the core genome and pan-genome. Means are plotted with 25 and 75 percentiles.

Genomic Flux

The results presented above address homologous recombination of the core genome, where one stretch of homologous DNA is replaced by another. In this section, we address nonhomologous recombination (also referred to as horizontal or lateral gene transfer) in the accessory genome. Nonhomologous recombination results in acquisition of novel sequences or loss of existing sequences, thereby determining the gene content of the accessory genome. These patterns of genomic flux were estimated by modeling the gain and loss of accessory genome features along the branches of the core phylogeny using the program GenoPlast (Didelot et al. 2009). Genomic flux along terminal branches ranged from net gains of + 11.29% to net losses of −2.43% of the included accessory features (mean = + 1.58% [SE = 0.56]), most of which represented gains of genomic regions unique to single isolates (supplementary fig. S5, Supplementary Material online). As expected, genome flux was positively correlated with the amount of accessory genome possessed by an isolate (P < 0.0001). Most of the basal, internal nodes of the tree had near-zero net fluxes (<|0.02%|), but interestingly, the internal node with highest flux was that subtending LESA. The net genomic flux of the LESA branch was +3.65%, indicating that this epidemic clade tends to acquire accessory genome content. Consistent with this, LESA isolates had an average of 70 kb more accessory genome than non-LESA isolates (n.s., P > 0.18).

The transfer of DNA in Pseudomonads typically occurs cell-to-cell via conjugation or from phage via transduction, and evidence of such activity is imprinted in most P. aeruginosa genomes (Kung et al. 2010). We searched for similar evidence in the regions of accessory genome that were exclusive to all LESA isolates. As we reported previously (Dettman et al. 2013), 85 kb of LESA-specific accessory sequence was distributed in five main genome regions, most of which overlapped with previously described genome features of LESA (Winstanley et al. 2009). Predictions of genomic islands based on abnormal sequence composition (IslandViewer, Langille and Brinkman 2009) also suggested these regions were horizontally transferred (supplementary fig. S6, Supplementary Material online). In addition, these LESA-specific regions contained, or were flanked closely by, numerous genes associated with mobile genetic elements or phage activity (e.g., integrases, excisionases, transposases, and inverted repeats). The only other genes in the LESA-specific accessory genome with functional importance were transport related, several of which are known to efflux heavy metals and antibiotics (Dettman et al. 2013).

We also searched for accessory genome regions that were lost exclusively in LESA. However, no regions fulfilled the criteria of being absent in all LESA isolates but present in all other isolates. Even when we relaxed the threshold to presence in greater than 75% of other strains, only 9 kb of accessory sequence was found. All ten of the encompassed genes were phage-related or hypothetical proteins and, therefore, did not appear to have any functional significance.

Accessory Genome Phylogeny

Mosaic patterns were observed in the shared presence/absence of accessory genome content among isolates. The phylogenetic tree constructed from a distance matrix based on the presence/absence of accessory regions (supplementary fig. S7, Supplementary Material online) was similar to the core genome trees shown figure 2; it was star-shaped and the basal relationships among strains were poorly resolved. Once again, Clades A, B, C, and E were identified, suggesting that the exchange of accessory genome among lineages has been low enough to retain the underlying phylogenetic structure of the core genome.

Characteristics of Genome Regions with High Levels of Homologous Recombination

Distribution of Recombination Events

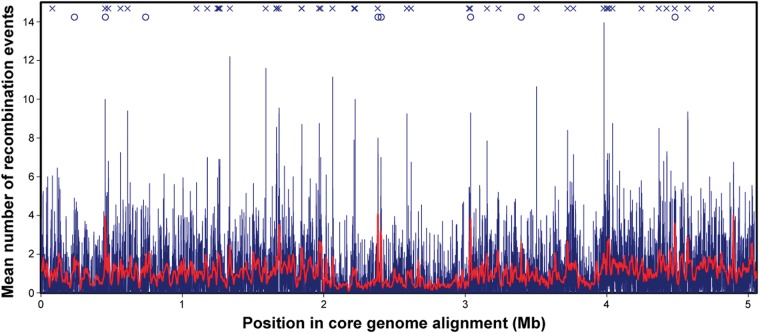

Mutation and recombination events were assigned to specific branches of the core phylogeny, and the number of recombination events affecting each site in the core alignment was calculated. This metric indicates the extent to which an individual site has experienced recombination in the history of the sample, and is directly comparable between sites. The results, shown in figure 5, reveal substantial variation in the frequency of recombination events along the core genome but with no large “hotspots” of recombination in particular genomic regions.

Fig. 5.—

Plot of the number of recombination events along the core genome alignment. Values are means calculated from a sliding window of 500 sites (thick red line) or 20 sites (thin blue line). Crosses along the top indicate regions with high frequency of recombination. Circles along the top indicate regions with high nucleotide diversity (from Dettman et al. 2013).

Genome stretches where multiple consecutive reference sites experienced high numbers of recombination events were identified. As expected, some of these regions coincided with regions of high nucleotide diversity (fig. 5). Next, the characteristics of genes located within the top approximately 50 regions affected the most by recombination were examined. Inspection of available GO information for the 54 genes with a history of frequent recombination revealed that the most represented GO classes were related to the cell wall, membranes, transport, and response to stimuli (supplementary fig. S8A, Supplementary Material online).

Detailed manual annotation (table 3) confirmed that many genes had roles specific to secretion (tssA1, pilD, PA5090), iron transport (fiuA, bfrA, PA5248), and cell wall/biofilm formation (waaL, wapR, wbpM, murB, lepA, PA3127, PA5249). Genes associated with resistance to organic solvents, hydroperoxides, and antibiotics were also represented (ampE, ostA, ohr, ohrR, opmE). Many of these genes are within functional classes or pathways with direct relevance to CF lung pathosystem (see Discussion).

Table 3.

List of Genes within Core Genome Regions of High Recombination

| Functional Class | Gene ID in PAO1 | Functional Information from Pseudomonas aeruginosa Annotations, Homology Searches, and Structural Features |

|---|---|---|

| Secretion and transport | PA0082 | tssA1, type-VI secretion protein |

| PA0470 | fiuA, ferrichrome receptor, iron binding and transport | |

| PA4235 | bfrA, bacterioferritin A (cytochrome b1), ferric iron binding and transport | |

| PA3670 | Auxiliary component of ABC transporter, gliding motility | |

| PA3597 | Amino acid permease, ABC transporter | |

| PA3520 | Putative heavy metal binding protein, transport/detoxification, copper binding | |

| PA4541 | lepA, secreted protease, filamentous hemagglutinin, adherance to host or biofilm | |

| PA4770 | lldP, L-lactate permease, monocarboxylic acid transport | |

| PA4898 | opdK, outer membrane vanillate porin, oprD family | |

| PA5090 | Type-VI secretion protein, Rhs element, Vgr-family protein | |

| PA5248 | Cytochrome c/iron permease family protein | |

| PA5249 | Amino acid/homoserine lactone transporter, quorum sensing and biofilm formation | |

| Cell wall metabolism | PA3734 | Putative lipase |

| PA3239 | Putative vacJ-family surface lipoprotein | |

| PA3141 | wbpM, nucleotide sugar epimerase/dehydratase, LPS biosynthesis | |

| PA3127 | Putative bleomycin resistance protein, glyoxalase/dioxygenase | |

| PA2977 | murB, UDP-N-acetylenolpyruvylglucosamine reductase, peptidoglycan biosynthesis | |

| PA2403 | Peptidase, iron-regulated membrane protein | |

| PA4528 | pilD, type IV prepilin peptidase, fimbrial biogenesis protein, adherance to host or biofilm | |

| PA4999 | waaL, O-antigen ligase, LPS biosynthesis, attaches O-antigen repeats to the lipid-A core | |

| PA5000 | wapR, alpha-1,3-rhamnosyltransferase, LPS biosynthesis, biofilm formation | |

| PA5089 | Putative phospholipase | |

| Resistance | PA0595 | ostA, organic solvent tolerance protein precursor, LPS transport protein |

| PA3521 | opmE, outer membrane efflux protein, multidrug resistance | |

| PA2850 | ohr, organic hydroperoxide resistance protein, peroxiredoxin, oxidative stress resistance | |

| PA2849 | ohrR, organic hydroperoxide resistance transcriptional regulator, multiple antibiotic resistance repressor (MarR) family, regulator of oxidative stress response | |

| PA4521 | ampE, inner membrane protein required for beta-lactamase induction, antibiotic resistance | |

| Miscellaneous | PA0495 | Putative hydrolase, urea metabolism |

| PA4234 | uvrA, excinuclease ABC subunit A | |

| PA3735 | thrC, threonine synthase | |

| PA3669 | Hypothetical protein | |

| PA3596 | Probable methylated-DNA-protein-cysteine methyltransferase | |

| PA3589 | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase, acyl-CoA thiolase | |

| PA3240 | Conserved hypothetical protein, pirin-related protein | |

| PA3163 | cmk, cytidylate kinase, pyrimidine metabolism | |

| PA2978 | ptpA, phosphotyrosine protein phosphatase | |

| PA2976 | rne, ribonuclease E | |

| PA2852 | Hypothetical protein | |

| PA2839 | ygiD, aromatic ring dioxygenase | |

| Not called | Hypothetical protein (pseudogene) | |

| PA2573 | Chemotaxis transducer, methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein | |

| Not called | Hypothetical protein | |

| PA1930 | Chemotaxis transducer, methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein | |

| Not called | Putative GntR-family transcriptional regulator | |

| PA1510 | Hypothetical membrane protein | |

| PA1509 | Hypothetical protein | |

| PA1377 | yhhY, acetyltransferase | |

| PA1394 | Hypothetical protein | |

| PA1267 | Putative D-amino acid oxidase, FAD-dependent oxidoreductase | |

| PA0711 | Probable acetyltransferase | |

| PA0710 | gloA2, lactoylglutathione lyase, glyoxalase I | |

| PA4523 | Probable thymidine phosphorylase | |

| PA4524 | nadC, nicotinate-nucleotide pyrophosphorylase | |

| PA4949 | yjeF, putative carbohydrate kinase |

Epidemic Strains (LESA and ESB)

Given the clinical importance and unique characteristics of LESA, we investigated which genes in the core genome were affected by homologous recombination in this particular strain. We found 75 regions of recombinant origin (>500 bp) that mapped to the LESA branch. Annotation of these genes revealed many functions related to the cell wall and membranes (supplementary table S3 and fig. S8B, Supplementary Material online) including transport, secretion, adherence (biofilm and fimbriae formation), and metabolism of peptidoglycan and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) cell wall components (see examples in supplementary table S3, Supplementary Material online). All of these functions are related to the virulence or pathogenicity of P. aeruginosa in context of the CF lung (see Discussion). Oxidation/reduction and arginine/polyamine metabolism were also commonly represented functional classes, both of which were previously identified as pathways under selection in these clinical P. aeruginosa isolates (Dettman et al. 2013).

Genomic regions of recombinant origin shared between LESA and ESB are of particular interest because they are potentially associated with the epidemic nature of both of these clades. We found 32 such shared genomic regions (table 4) that contained genes with functions such as type-VI secretion (IcmF1, PA5090), efflux (PA4136, PA4779), cytochrome c biogenesis (ccmA, ccmB, PA4571), arginine/polyamine metabolism (bauR, argB), adhesion (cupB5), and peptidoglycan metabolism (mltB1, mrcB).

Table 4.

List of Genes within Regions of Recombinant Origin Shared between Two Epidemic Strains (LESA and ESB)

| Gene ID in PAO1 | Gene ID in LESB58 | Functional Information from Pseudomonas aeruginosa Annotations, Homology Searches, and Structural Features |

|---|---|---|

| PA0077 | PALES_00781 | icmF1, type-VI secretion protein, inner-membrane protein |

| PA0133 | PALES_01341 | bauR, LysR-family transcriptional regulator, beta-alanine/polyamine metabolism |

| PA0349 | PALES_03461 | Hypothetical protein |

| PA0480 | PALES_04761 | Hydrolase, 3-oxoadipate enol-lactonase |

| PA0556 | PALES_05541 | Hypothetical protein |

| PA0588 | PALES_05851 | PrkA-family serine protein kinase (yeaG) |

| PA4136 | PALES_08351 | Major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporter, multidrug efflux |

| PA4082 | PALES_08941 | cupB5, adhesive protein, adherance to host or biofilm |

| PA3895 | PALES_10821 | LysR-family transcriptional regulator |

| PA3778 | PALES_11961 | LysR family transcriptional regulator |

| PA3589 | PALES_14451 | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase, acyl-CoA thiolase |

| PA3324 | PALES_17401 | Short chain dehydrogenase |

| PA3272 | PALES_17951 | ATP-dependent DNA helicase |

| PA2873 | PALES_21911 | tgpA, transglutaminase protein A |

| PA1375 | PALES_38101 | pdxB, erythronate-4-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| PA1476 | PALES_39371 | ccmB, cytochrome c-type biogenesis protein |

| PA1475 | PALES_39381 | ccmA, cytochrome c biogenesis ATP-binding export protein |

| PA0671 | PALES_46581 | Hypothetical protein |

| PA4444 | PALES_48231 | mltB1, lytic transglycosylase, murein hydrolase, peptidoglycan metabolism |

| PA4523 | PALES_49041 | Thymidine phosphorylase |

| PA4543 | PALES_49261 | Multicopper polyphenol oxidoreductase |

| PA4571 | PALES_49541 | Cytochrome c |

| PA4700 | PALES_50851 | mrcB, penicillin-binding protein 1B, membrane carboxypeptidase, peptiglycan metabolism, antibiotic resistance |

| PA4701 | PALES_50861 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| PA4733 | PALES_51181 | acsB, acetyl-CoA synthetase |

| PA4779 | PALES_51641 | ABC transporter permease |

| PA5090 | PALES_54801 | Type-VI secretion protein, Rhs element, Vgr-family protein |

| PA5323 | PALES_57181 | argB, acetylglutamate kinase, arginine/ornithine metabolism |

| PA5324 | PALES_57191 | Transcriptional regulator, AraC family |

| PA5349 | PALES_57441 | Rubredoxin-NAD(+) reductase |

Homologous and nonhomologous recombination were not colocalized within the genome. When we compared the distribution of homologous recombination in LESA to the distribution of LESA-specific accessory regions, we found that the two types of recombination typically occurred in distinct genome regions and the five LESA-specific accessory regions were not in close proximity to regions of high homologous recombination. The average distance from an external edge of a LESA-specific accessory island to the nearest LESA homologous recombination tract edge was 135.1 kb (SE = 44.4), providing no evidence for colocalization.

Recombination and Positive Selection

Recombination is inferred by the distribution and patterns of inheritance of SNPs, whereas the inference of selection relies more on the characteristics of the SNPs and their effects on the protein. Nevertheless, the clustered polymorphisms introduced by recombination may contribute to increased signatures of positive selection. We explored this possibility using the dN/dS (omega) data from our previous gene-based selection analyses (Dettman et al. 2013). Genes within regions of frequent recombination (table 3), or of recombinant origin in both epidemic strains (table 4), had mean omega values of 0.115 (SE = 0.012) and 0.095 (SE = 0.013), respectively. Neither of these means was significantly different from that for all core genes (0.099, SE = 0.002; P = 0.41 and 0.84, respectively), indicating that recombination did not have a strong influence on this metric of positive selection.

Discussion

Recombination can be a potent force generating strain-specific variation in microbial populations. To shed light on the role of recombination in governing the evolutionary dynamics of P. aeruginosa infections of adult CF patients, we have studied the genome-wide rate and extent of recombination among 32 clinical isolates. We used a suite of currently available tools for inferring recombination from genomic data to provide a comprehensive view of recombination’s impact on genomic evolution and variation among clinically relevant strains. One main finding is that recombination contributes substantially to the global pool of genetic variation in P. aeruginosa, providing the source material from which clinical infections originate. Once established in the lung, further adaptation appears to be driven primarily by mutation and clonal selection. Another main finding is that genes in high-recombination regions commonly had cell wall-related functions, suggesting that the products of recombination may be maintained by selection for variation in cell-surface molecules that allows for evasion of the host immune system. Below we review the main features of our results that lead us to these conclusions and discuss in more detail the biology of genomic regions subject to high rates of recombination

Effect of Recombination

We estimate the impact of recombination relative to mutation (r/m) in our strain collection to be 0.85. Other studies that have applied similar genome-wide approaches to pathogenic bacteria such as Chlamydia trachomatis (Joseph et al. 2012), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Namouchi et al. 2012), and Clostridium difficile (He et al. 2010) have reported r/m in the range of 0.45–1.20, so P. aeruginosa has an intermediate level of recombination. It is notable that recent work with MLST data for P. aeruginosa isolates from human, animal, and environmental sources also found evidence for frequent recombination, although r/m values tend to be much higher than our estimate, in the range of 8.4–9.5 (Maatallah et al. 2011; Kidd et al. 2012). Differences in r/m may reflect genuine variation among populations of P. aeruginosa or may be due to systematic biases between MLST and whole-genome methods. For example, it may be that MLST data inflates r/m estimates because it is based on far more restricted genome sampling than whole-genome approaches and so is likely to lead to lower estimates of m relative to r. A more systematic comparison of these two methods is needed to test this hypothesis.

Extent of Recombination

Homologous recombination in the core genome introduces short tracts of DNA, with an average recombination tract length (δ) of 273 bp, which is in the range of previous results from other bacteria (Joseph et al. 2012; Namouchi et al. 2012). LD, the tendency for multiple SNPs to be found together more often than expected by chance, decays rapidly over the first few hundred bases and then plateaus near an r2 of 0.2. This pattern of LD decay is very similar to that seen, for example, in M. tuberculosis (Namouchi et al. 2012). Together, these results suggest that there is nothing unusual or unique about the process of homologous recombination in P. aeruginosa compared with other bacteria.

There is also nothing particularly unusual about the process of nonhomologous recombination in P. aeruginosa relative to other bacterial species. On average, the accessory genome accounted for 16% of total genome size, in line with that observed for strain variation within species in other bacteria (Segerman 2012). Genomic flux was on average positive, indicating that there is a tendency for strains to acquire genomic elements through nonhomologous recombination.

Recombination and Adaptation to the CF lung

Recombination can facilitate adaptive evolution in general, and to the CF lung environment in particular, by introducing novel genetic variation on which selection can act. If the imported allele confers a fitness advantage to the recipient, it will have an increased probability (relative to a neutral allele) of reaching fixation, and of being maintained in the population, thereby leaving a genomic signature of recombination. If the imported allele is detrimental, it will tend to be purged from the population, and evidence for that recombination event will be eradicated. Neutral alleles also have very low probabilities of fixation, so in sum, regions of the genome that are detectably of recombinant origin are most likely to be enriched for adaptively beneficial alleles. Furthermore, neutral alleles that do fix would be distributed randomly among the classes of gene function. The fact that many of our candidate genes have known functions in pathways associated with the P. aeruginosa/CF pathosystem indicates our analyses were able to identify the signal of selection over a background of neutral evolution.

The important functional pathways identified here by recombination analyses are remarkably similar to those implicated previously using various comparative genomic analyses (Dettman et al. 2013). Many of the candidate genes associated with adaptation to the CF lung environment were involved in biofilm formation, pathogenesis, transmembrane transport, and secretion, but the main factors driving adaptation to the host appeared to be resistance to oxidative stressors and antibiotics. These results were paralleled by the characteristics of the candidate genes in regions of high recombination we discuss here. Finding that these different types of analyses converge on the same functional pathways, but typically pinpoint different sets of genes, further highlights the importance of these key genetic pathways in adaptation to the CF lung.

Many high-recombination genes had functional associations with the cell surface, including processes such as transmembrane transport, secretion, membrane biogenesis and lysis, biofilm formation, and adhesion (see tables 3 and 4 and supplementary table S3, Supplementary Material online). One can easily envision how adaptation can occur by obtaining new alleles that increase the activity of particular membrane transport functions, such as antibiotic efflux or the secretion of antibacterial or host-modulating effectors. Similarly, alleles that stabilize the integrity of the membrane or increase resistance to various environmental stressors could also be selected for. The ability to adhere to the host, or to form strong biofilms that protect the cells from antibiotic exposure would also be under positive selection in the CF lung environment. Pathogenesis is a tightly coordinated action controlled by several of these virulence-related processes. Such functions are clearly relevant to the CF lung pathosystem and are discussed in more detail below, including examples of how key genes identified in our analysis may be adaptive.

Transport

All substrates that enter or leave the bacterial cell must pass through the cell wall via transmembrane transport systems. The uptake of growth-limiting nutrients and the efflux of toxic compounds are both essential processes for survival in any environment. Several transport-related genes were on our gene lists (tables 3 and 4 and supplementary table S3, Supplementary Material online) such as permeases, porins, ABC transporters, and MFS transporters. Of particular interest are efflux pumps because they often have wide substrate ranges including the export of sugars, heavy metals, and multiple classes of antibiotics. Examples include opmE, part of an RND efflux pump operon that influences multidrug resistance (Mima et al. 2005) and ampE, which regulates the induction of resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics (Langaee et al. 1998).

Secretion

Pseudomonas aeruginosa has an arsenal of complex secretion systems (Bleves et al. 2010) that release a wide variety of exoproteins. Many toxins and hydrolytic enzymes are involved in mediating competition among different bacterial strains or species (Bakkal et al. 2010; Schoustra et al. 2012), which is particularly relevant in the polymicrobial environment that typifies the CF lung (Hauser et al. 2014). We found many secretion-related genes in our candidate lists, such as tssA1 and icmf1. Both of these genes are located within the type-VI secretion system island H1-T6SS, a known virulence locus in P. aeruginosa (Potvin et al. 2003; Mougous et al. 2006, Hood et al. 2010). Others genes (lepA, lepB, eprS, and ptpA; table 3 and supplementary table S3, Supplementary Material online) can alter the physiology of the host cells to the advantage of the bacteria and contribute to the virulence and growth of P. aeruginosa in vivo (Kida et al. 2011, 2013).

Membrane Biogenesis and Lysis

The basal permeability of the outer membrane can affect a cell’s susceptibility to antibiotics and other environmental stressors. Several of the genes on the high-recombination lists played roles in the biogenesis of cell wall components. Multiple genes had functions in the metabolism of peptidoglycans (mureins), which form a mesh-like matrix within the periplasm and provide structural support to the cell wall. For example, murB, glmU, and mltB1 perform essential reactions in peptidoglycan biosynthesis and degradation pathways (Benson et al. 1995). The mrcB gene, which encodes a penicillin-binding protein (1B), is responsible for the polymerization of peptidogycan units and is a molecular target for B-lactam antibiotics.

Genes associated with LPS biosynthesis were also common. LPS contributes to the structural integrity of the membrane but also acts as an endotoxin that elicits a strong immune response from the host. Candidate genes such as waaL (O-antigen ligase), wbpM, and wapR are involved in the synthesis of the O-antigen portion of the LPS. Mutations in wbpM and variation in activity of wapR are known to alter the LPS phenotype and susceptibility to various antibiotics (Dotsch et al. 2009; Kocincova et al. 2012). Interestingly, the wbpM locus appears to be a target site for exchange of O-antigen genes (Rocchetta et al. 1999), potentially explaining the history of high recombination detected here.

Adhesion and Biofilm Formation

Several genes involved in production of pili or fimbriae also appeared on the gene lists (pilD, pilR, cupB5, cupE5). Type-IV pili mediate several disparate functions in bacteria, such as motility, surface adhesion, protein secretion, and the uptake of DNA (competence). For example, type-IV pili are the major virulence-associated adhesin in P. aeruginosa (Hahn 1997) and facilitate the transfer of pathogenicity islands between strains (Carter et al. 2010). Disruption of the high-recombination type IV pilin gene, pilD, results in strongly attenuated in vivo virulence (Potvin et al. 2003). A gene of recombinant origin in both epidemic strains was cupB5, a fimbriae-related gene that plays a role in biofilm formation and adhesion. EstA, an autotransporter esterase, is also required for biofilm formation and in vivo virulence (Potvin et al. 2003; Wilhelm et al. 2007). Many of the genes that affect the production of cell surface components also affect the formation of biofilms and general adhesion characteristics.

Oxidative Stress Resistance

One of the host’s front line defences against infection is to produce an oxidative burst, in which various reactive oxygen species (ROS) are released to create an unfavorable environment for the bacteria. Many genes associated with detoxification and management of oxidative stress were on our gene lists, including those related to cytochrome c biogenesis as well as those with dioxygenase, glyoxalase, dehyrogenase, and oxidoreductase activity. Of special interest were two genes (ohr and ohrR) within an operon that confers resistance to organic hydroperoxides (OHP), a ROS produced by activated host defence mechanisms and as a by-product of normal aerobic respiration in bacteria. ohrR, a member of the MarR (Multiple antibiotic resistance) family, encodes an oxidation-sensing transcription factor that directly regulates the expression of ohr. In P. aeruginosa, ohrR mutants show increased resistance to OHPs and reduced virulence in a laboratory infection model (Atichartpongkul et al. 2010).

Regions under Diversifying Selection

If a gene is under diversifying selection, the characteristics of the alleles themselves may be less important than the fact that they differ from other alleles in the population. A prime example of where diversity would be beneficial is the loci that determine the serotype (antigenic specificity) of a bacterial cell. Novel serotypes that are capable of evading the adaptive immune response of the host are likely to be favoured. Recombination events that diversify the antigenic specificity of the cell surface can play an important role in this process. Consistent with this idea, many of the recombination-associated genes discussed above were involved in the synthesis of cell wall components LPS and peptidoglycan, the main immunogenic molecules detected by the host’s immune system for Gram-negative bacteria like P. aeruginosa. For example, wbpM, waaL, and wapR are three genes central to the O-antigen synthesis pathway. O-antigen is the terminal portion of the LPS molecule that determines antigenic specificity of the mature LPS. We hypothesize that the highly recombining nature of these O-antigen genes explains why modification or complete loss of expressed O-antigen is a common change observed in P. aeruginosa isolates from CF lungs (Hancock et al. 1983; Spencer et al. 2003; Smith et al. 2006) and why O-antigen genes can be highly diverse within P. aeruginosa populations (Dettman et al. 2013). Other putative examples of diversifying selection include those genes involved in peptidoglycan synthesis and iron uptake via siderophores and cognate receptors (e.g., fiuA, ferrichrome receptor).

Epidemic Strains

Genome sequence data recently confirmed that the most common epidemic of strain of P. aeruginosa in North America is the same as the most common epidemic strain in the United Kingdom (Winstanley et al. 2009; Dettman et al. 2013; Jeukens et al. 2014). Infection with this epidemic strain, LESA, is associated with significantly worse clinical outcomes of CF patients (i.e., lung transplant or death) when compared with infection with nonepidemic strains (Aaron et al. 2010). The genetic factors underlying increased transmissibility and virulence of LESA are not known, but our previous evolutionary genomics study found that LESA had acquired particular accessory genome regions that no other strains possessed. The present analysis shows that LESA has a preponderance for accessory genome gain, rather than loss, and that LESA has an average of 70 kb more accessory genome than other strains. The LESA-specific accessory genome is enriched for transporters and efflux pumps with affinities for binding and efflux of multiple classes of antibiotics, which likely contributes to the increased multidrug resistance profile of this epidemic strain (Beaudoin et al. 2010; Dettman et al. 2013).

A noteworthy class of genes affected by recombination in the epidemic strains were those involved in the metabolism of arginine, ornithine, and polyamines. Six genes in this class were flagged in LESA (bauR, argB, potC, caiX, cdhR, betT2; supplementary table S3, Supplementary Material online), two of which were of recombinant origin in both epidemic strains (bauR, argB; table 4). Our previous study (Dettman et al. 2013) also found that several genes in arginine and polyamine metabolism contributed strongly to the sequence divergence of LESA from all other strains, but these were different genes (aguB, spuF, aotP) that did not overlap with recombination-associated genes identified here.

The arginine and polyamine metabolic pathways can be linked in three ways to CF lung adaptation. First, bacteria and macrophages both synthesize nitric oxide, an important ROS, from arginine precursors. Second, P. aeruginosa catabolizes arginine during anaerobic growth and preferentially consumes amino acids, such as arginine, when grown in approximated CF lung conditions (Palmer et al. 2007). Third, bacterially produced polyamines, which can inhibit the host’s oxidative burst response (Regunathan and Piletz 2003), are synthesized from arginine precursors. The fact that different analyses found different sets of genes involved in arginine and polyamine metabolism underscores the importance of these pathways as targets of adaptive evolution of epidemic strains of P. aeruginosa.

Phylogeny, Recombination, Adaptive Radiation, and Population Structure

Different genomic regions can have distinct histories of evolutionary descent, but our use of whole-genome sequence data allows us to infer phylogenies using the maximum amount of available data. Despite the strong evidence for appreciable rates of recombination in these P. aeruginosa genomes, our phylogenetic analyses consistently identified the same set of clades (Clades A–E) as distinct in both core and accessory genomes. In contrast, the basal relationships among strains were poorly resolved and the trees tended to have long terminal branches and short, weakly supported internodes. Widespread recombination is commonly invoked to explain the lack of basal phylogenetic structure, but when we accounted for recombination using two different methods, neither significantly improved the resolution of the phylogeny (fig. 2). Our analyses suggest that contemporary gene flow among lineages is fairly low, and that the bulk of the recombination events occurred prior to, or during, the divergence of these phylogenetically distinct lineages from each other.

Based on the analyses presented here, and those from previous studies of the population structure of P. aeruginosa (Kiewitz and Tummler 2000; Pirnay et al. 2009; Maatallah et al. 2011; Kidd et al. 2012; Dettman et al. 2013), our working hypothesis for the development of chronic infections of the CF lung is as follows: There is a large, global, recombining population of P. aeruginosa that exists in a wide range of environmental niches, creating a reservoir of isolates that can potentially infect the lungs of CF patients. As such, there is little association between the strain and the source from which it was sampled (environmental, animal, non-CF human, CF human; Kidd et al. 2012) and environmental and clinical isolates are typically indistinguishable (Pirnay et al. 2009). Once inside the human host, strains that can rapidly adapt via mutation to the inhospitable conditions of the CF lung will survive and eventually form chronic infections typical of this pathogen (Smith et al. 2006; Cramer et al. 2011; Yang et al. 2011; Dettman et al. 2013). Each strain evolves more or less independently, within a single host, with limited genetic exchange among strains from other hosts or environmental sources. If a strain adapts particularly well, or develops increased transmissibility among hosts, it may increase in frequency and be detected as an epidemic strain. To date, whole-genome population-level analyses of P. aeruginosa have been restricted to isolates of human origin, mainly from chronic CF infections. For testing some of the predictions of this hypothesis, obtaining whole-genome data from a large number of environmental, animal, and non-CF human isolates, and determining their phylogenetic relationships with CF isolates, will be essential. A major challenge for future research will be to distinguish between the functional and genetic characteristics of clinical strains that govern the various processes of infection, such as lung colonization, virulence, persistence as a chronic infection, and progression of disease in the host.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures S1–S8 and tables S1–S3 are available at Genome Biology and Evolution online (http://www.gbe.oxfordjournals.org/).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gabriel Perron and two anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions. This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (#220426) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Literature Cited

- Aaron SD, et al. Infection with transmissible strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and clinical outcomes in adults with cystic fibrosis. JAMA. 2010;304:2145–2153. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Aloul M, et al. Increased morbidity associated with chronic infection by an epidemic Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain in CF patients. Thorax. 2004;59:334–336. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.014258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong DS, et al. Detection of a widespread clone of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a pediatric cystic fibrosis clinic. Am J Respir Crit Care. 2002;166:983–987. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200204-269OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atichartpongkul S, Fuangthong M, Vattanaviboon P, Mongkolsuk S. Analyses of the regulatory mechanism and physiological roles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa OhrR, a transcription regulator and a sensor of organic hydroperoxides. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:2093–2101. doi: 10.1128/JB.01510-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awadalla P. The evolutionary genomics of pathogen recombination. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:50–60. doi: 10.1038/nrg964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkal S, Robinson SM, Ordonez CL, Waltz DA, Riley MA. Role of bacteriocins in mediating interactions of bacterial isolates taken from cystic fibrosis patients. Microbiology. 2010;156:2058–2067. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.036848-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin T, Aaron SD, Giesbrecht-Lewis T, Vandemheen K, Mah TF. Characterization of clonal strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from cystic fibrosis patients in Ontario, Canada. Can J Microbiol. 2010;56:548–557. doi: 10.1139/w10-043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson TE, Filman DJ, Walsh CT, Hogle JM. An enzyme-substrate complex involved in bacterial-cell wall biosynthesis. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:644–653. doi: 10.1038/nsb0895-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleves S, et al. Protein secretion systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a wealth of pathogenic weapons. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300:534–543. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter MQ, Chen JS, Lory S. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenicity island PAPI-1 Is transferred via a novel type IV pilus. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:3249–3258. doi: 10.1128/JB.00041-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer N, et al. Microevolution of the major common Pseudomonas aeruginosa clones C and PA14 in cystic fibrosis lungs. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:1690–1704. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran B, Jonas D, Grundmann H, Pitt T, Dowson CG. Development of a multilocus sequence typing scheme for the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:5644–5649. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5644-5649.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT. progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettman JR, Rodrigue N, Aaron SD, Kassen R. Evolutionary genomics of epidemic and nonepidemic strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:21065–21070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307862110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didelot X, Darling A, Falush D. Inferring genomic flux in bacteria. Genome Res. 2009;19:306–317. doi: 10.1101/gr.082263.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didelot X, et al. Recombination and population structure in Salmonella enterica. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didelot X, Falush D. Inference of bacterial microevolution using multilocus sequence data. Genetics. 2007;175:1251–1266. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.063305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didelot X, Maiden MCJ. Impact of recombination on bacterial evolution. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotsch A, et al. Genomewide identification of genetic determinants of antimicrobial drug resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2522–2531. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00035-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright MC, et al. The evolutionary history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7687–7692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122108599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics. 2003;164:1567–1587. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.4.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotz S, et al. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3420–3435. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, et al. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn HP. The type-4 pilus is the major virulence-associated adhesin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa—a review. Gene. 1997;192:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock REW, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis: a class of serum-sensitive, nontypable strains deficient in lipopolysaccharide O side-chain. Infect Immun. 1983;42:170–177. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.1.170-177.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser AR, Jain M, Bar-Meir M, McColley SA. Clinical significance of microbial infection and adaptation in cystic fibrosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:29–70. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00036-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser PM, et al. Microbiota present in cystic fibrosis lungs as revealed by whole genome sequencing. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M, et al. Evolutionary dynamics of Clostridium difficile over short and long time scales. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7527–7532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914322107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood RD, et al. A type VI secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa targets a toxin to bacteria. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson DH, Bryant D. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:254–267. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RW, Vinatzer B, Arnold DL, Dorus S, Murillo J. The influence of the accessory genome on bacterial pathogen evolution. Mob Genet Elements. 2011;1:55–65. doi: 10.4161/mge.1.1.16432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeukens J, et al. Comparative genomics of isolates of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa epidemic strain associated with chronic lung infections of cystic fibrosis patients. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87611. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph SJ, et al. Population genomics of Chlamydia trachomatis: insights on drift, selection, recombination, and population structure. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:3933–3946. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kida Y, Shimizu T, Kuwano K. Cooperation between LepA and PlcH contributes to the in vivo virulence and growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Mice. Infect Immun. 2011;79:211–219. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01053-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kida Y, Taira J, Yamamoto T, Higashimoto Y, Kuwano K. EprS, an autotransporter protein of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, possessing serine protease activity induces inflammatory responses through protease-activated receptors. Cell Microbiol. 2013;15:1168–1181. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd TJ, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exhibits frequent recombination, but only a limited association between genotype and ecological setting. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiewitz C, Tummler B. Sequence diversity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: impact on population structure and genome evolution. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3125–3135. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.11.3125-3135.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocincova D, Ostler SL, Anderson EM, Lam JS. Rhamnosyltransferase genes migA and wapR are regulated in a differential manner to modulate the quantities of core oligosaccharide glycoforms produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:4295–4300. doi: 10.1128/JB.05741-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung VL, Ozer EA, Hauser AR. The Accessory genome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2010;74:621–641. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00027-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langaee TY, Dargis M, Huletsky A. An ampD gene in Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a negative regulator of AmpC beta-lactamase expression. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3296–3300. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.12.3296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langille MGI, Brinkman FSL. IslandViewer: an integrated interface for computational identification and visualization of genomic islands. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:664–665. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1451–1452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]