Abstract

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology offers new opportunities for understanding the evolution and dynamics of viral populations within individual hosts over the course of infection. We review simple methods for estimating synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide diversity in viral genes from NGS data without the need for inferring linkage. We discuss the potential usefulness of these data for addressing questions of both practical and theoretical interest, including fundamental questions regarding the effective population sizes of within-host viral populations and the modes of natural selection acting on them.

Keywords: next-generation sequencing, nucleotide diversity, quasispecies, synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution

1. Introduction

Because of the rapid generation times and high mutation rates of most viruses, the virus population infecting an individual host can accumulate substantial genetic diversity over the course of infection. This diversity is in turn subject, like genetic diversity in any biological population, to the processes of natural selection and random genetic drift, which determine whether individual variants increase or decrease in frequency. Thus, the viral population infecting an individual host is subject to an evolutionary process. This evolutionary process may be important for the persistence of viral infection; for example, the host immune system may selectively favor viral variants that evade immune recognition. For this reason, understanding within-host viral evolution has been a major focus of research aiming to understand the mechanisms by which certain viruses, such as human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), evade clearance by the host immune system and thus establish persistent infections.

In spite of the importance of understanding within-host evolution of virus populations, it has been difficult to study this process until recently. The advent of so-called “next-generation” sequencing (NGS) technologies, with their potential to survey thousands of viral sequences from a given host, has dramatically improved our ability to characterize within-host sequence diversity in viral infections. NGS has been applied to address such questions as overall viral diversity within-hosts (Lauck et al. 2012; Wright et al. 2011); evolution of T-cell epitopes under selection by the host immune system (Bimber et al. 2010; Hughes et al. 2010, 2012; Mudd et al. 2012; O'Connor et al. 2012; Walsh et al. 2013); response of viruses to selection imposed by antiviral drugs (Cannon et al. 2008; Hedskog et al. 2010; Le et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2010a); differences between virus subpopulations infecting different host cell types (Rozera et al. 2009); and population bottlenecks in infection (Wang et al. 2010b).

Here we discuss statistical methods for using NGS data to understand nucleotide sequence diversity of within-host viral populations, with particular emphasis on the comparison of synonymous and nonsynonymous (amino acid-altering) nucleotide diversity in coding regions. NGS studies of within-host virus diversity use pooled samples, i.e., the genetic material of multiple individuals pooled in a single sample, as opposed to sequencing individual viral genomes separately. Besides saving costs, the sequencing of sufficiently large pools has been shown to give more accurate estimates of population genetic parameters than those obtained from individual sequencing (Futschik and Schlötterer 2010). Such studies can be categorized as follows: (1) targeted NGS, using primers that amplify a specific short region of the viral genome, such as a specific T-cell epitope, thereby providing the complete sequences of haplotypes spanning that region (Bimber et al. 2010); or (2) genome-wide NGS, using sets of primers designed to obtain sequence information across all or most of the viral genome (Hughes et al. 2012; Wilker et al. 2013; Bailey et al. 2014). In the former type of study, standard methods of statistical analysis of sequence data (Nei and Kumar 2000) are directly applicable, including the estimation of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide diversity and even phylogenetic tree reconstruction. However, because the sequence reads produced by NGS are short and thus provide limited information, phylogenetic trees are often poorly resolved in the case of targeted NGS.

In the case of genome-wide NGS, traditional techniques of sequence analysis are not directly applicable because of the lack of knowledge of haplotypes. Except when two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) occur in the same short read, these methods do not provide any direct evidence regarding the phase of SNPs, i.e., whether or not they occur together in the same haplotype. In some studies, determining haplotypes may be sufficiently important that researchers may want to make use of statistical methods for inferring haplotypes by assembling sequence reads (Beerenwinkel and Zagordi 2011). However, it is uncertain that haplotype inference will always be possible in the case of within-host viral populations, where all or most haplotypes may be very closely related and parallel mutations and recombination may obscure haplotype identities. Moreover, whenever haplotype inference is used, it must be kept in mind that any further inferences that rely on that inference remain conditional upon its accuracy.

For this reason, it may be useful in the case of whole-genome NGS to make use of methods that estimate population-level sequence parameters without the need to infer haplotypes. Here we discuss the theoretical basis of such methods and some examples of their application. We then briefly address the potential of these approaches for addressing some important theoretical and applied issues in the biology of viruses. As a specific example, we discuss how application of these approaches may provide data that will shed light on the relevance of the “quasispecies” model for understanding within-host evolution of viral populations.

2. Nucleotide Diversity

Nucleotide diversity (π) represents an important property of populations of nucleic acid sequences. In order to estimate nucleotide diversity in a population, we first take a random sample of n sequences from the population. Between each sequence and each other sequence, we estimate dij, the number of nucleotide substitutions per site. A number of models are available for estimating dij, correcting for multiple hits and taking into account the effects of base composition bias and transitional bias (Nei and Kumar 2000). In the case of within-host virus populations, dij values are generally quite low (usually much less than 10%), and therefore the effect of these corrections will be very slight; thus, the uncorrected proportion of nucleotide differences between sequences often provides an adequate estimate of dij. Nucleotide diversity (π) is estimated by the mean dij for all (n2-n)/2 possible pairwise comparisons among sequences; i.e.,

| (1) |

In the case of coding sequences, important evolutionary information can be gained by estimating nucleotide diversity separately for synonymous and nonsynonymous sites. First, we estimate for each pair of sequences the number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (dS) and the number of nonsynonymous substitutions per nonsynonymous site (dN). In addition to correction for multiple hits, there exist a variety of methods for estimating dS and dN that also take into account nucleotide content and transitional bias (Nei and Kumar 2000). In the case of within-host viral populations, since the degree of sequence divergence is usually slight, the use of complicated models for estimating dS and dN has little effect on the results. Thus, a simple method, such as that of Nei and Gojobori (1986), usually provides adequate results. Note that complex methods for estimating dS and dN, such as likelihood methods, generally estimate nucleotide frequencies and other such parameters from the sequences themselves; thus, this procedure can be positively misleading when the sequences analyzed are short, because the stochastic error of these estimates will be very high in the case of short sequences. These complex methods for estimating dS and dN should therefore be avoided in the analysis of short sequences, as in targeted NGS, or in the estimation of dS and dN in sliding windows along a gene.

In a population of sequences, let dSij be the estimate of dS between sequences i and j. The synonymous nucleotide diversity (πS) is estimated by substituting dSij for dij in equation (1). Similarly, let dNij be the estimate of dN between sequences i and j. The nonsynonymous nucleotide diversity (πN) is estimated by substituting dNij for dij in equation (1).

Selectively neutral nucleotide diversity provides an estimate of the population parameter θ, which is proportional to the product of the effective population size (Ne) and the mutation rate (ν) per generation (Li 1997; Nei and Kumar 2000). This relationship holds under the assumptions of the infinite-sites model of population genetics, when mutation and drift are in equilibrium (Nei and Kumar 2000). Since synonymous mutations are generally selectively neutral or nearly so, in the case of a haploid organism such as a virus, we expect

| (2) |

When we compare two populations of the same virus, we expect that ν will probably be the same in the two populations. Therefore, comparing πS in the two populations will provide an estimate of their relative effective population sizes.

In addition, the comparison of πS and πN provides information regarding the action of natural selection on the population of sequences under study. In most coding regions, πS substantially exceeds πN. This pattern occurs because most nonsynonymous mutations are deleterious and are therefore reduced in frequency or eliminated by purifying selection, whereas synonymous mutations are much more likely to be neutral or nearly neutral (Hughes 1999). The relative values of πS and πN are thus indicative of the strength and effectiveness of purifying selection. The strength of purifying selection reflects the functional importance of the protein or protein region being studied. In general, relative to πS, we expect πN to be lower in protein regions highly important to viral fitness than in protein regions that are less important to viral fitness.

When we have reason to suspect that positive Darwinian selection is acting to favor amino acid changes within a certain protein region, we may predict a reversal of the usual pattern, with πN greater than πS. An example of such a region would be a CD8+ TL epitope (Hughes et al. 2012); that is, a region of a viral protein that is recognized by a host class I major histocompatibility complex glycoprotein and presented to CD8+ T-lymphocytes (“cytotoxic T-cells”). In such a case, biological knowledge suggests a reason to expect repeated amino acid-altering changes in a region: namely, the evasion of the host immune system by the pathogen.

When there is no a priori reason to expect positive selection on some particular region of a viral protein, it may be useful to compute πS and πN in a sliding window along the gene. In the analysis of viruses infecting vertebrates, we frequently use a sliding window of 9 codons, because most CD8+ TL epitopes are nonamers (Evans et al. 1999; Hughes et al. 2001). Note that it is best to compute πS and πN separately, rather than to compute the ratio πN / πS as is sometimes done. Ratios have undesirable statistical properties, and are therefore best avoided. For example, in the case of closely related sequences and a short sliding window length, πS may often be zero in a given window, in which case the ratio πN / πS will be undefined. Additionally, examining the ratio πN / πS alone provides no information as to why that ratio is high in a given gene region. For example, the ratio πN / πS may be high in a certain region merely because πS is unusually low, while πN is not unusually high. In the latter case, high πN / πS would not be suggestive of positive selection but merely of some constraint on πS, such as a low mutation rate or some constraint on synonymous substitution such as purifying selection on codon usage. Moreover, in the case of viruses, the existence of overlapping reading frames often provides constraints on synonymous substitutions because substitutions that are synonymous in one reading frame may be nonsynonymous in another (Hughes et al. 2001; Hughes and Hughes 2005).

3. Next-Generation Sequencing Data

Nei and Kumar (2000, p. 251) note that nucleotide diversity is equivalent to “heterozygosity at the nucleotide level.” This relationship indicates that the estimation of nucleotide diversity across a genomic region does not require the availability of sequences (haplotypes) spanning the entire region, but rather only the frequency of different allelic variants at polymorphic sites. Thus, we can estimate nucleotide diversity from NGS data without reconstructing haplotypes, because NGS data provide information on the frequency of variants.

In order to estimate nucleotide diversity, we need to estimate the proportion of pairwise differences at each polymorphic site. Let mi designate the coverage provided at the ith site, i.e., the number of reads providing a base call for that site. The counts for the four bases at the ith site are designated, respectively, Ai, Ci, Gi, and Ti; thus mi = Ai + Ci + Gi+ Ti. The proportion of pairwise nucleotide differences at the ith site (Di) is given by:

| (3) |

In within-host virus population data, the majority of SNPs are biallelic. In that case, only one of the six summed terms in the numerator of (3) will be non-zero. More complicated situations arise when multiple SNPs occur at the same site, or when analyses are based on entire codons. In the former case, there will be a maximum of 6 possible non-zero pairs. In the latter case, equation (3) must be expanded to compare all 64 possible codons, which constrains the number of non-zero terms in the numerator by an upper bound of 64C2 = 2016 pairs of codons.

In order to estimate nucleotide diversity in non-coding regions (or without regard to coding differences in coding regions), for a sequence of L nucleotides and s polymorphic sites:

| (4) |

The same approach can be easily extended to estimate πS and πN in coding sequences. Diis estimated separately for synonymous and nonsynonymous sites using equation (3), while L represents the number of synonymous or nonsynonymous sites comprising the length of the sequence. This calculation obviously requires knowledge of a SNP's codon context. To compute synonymous Di at a site that is less than four-fold degenerate, only the nucleotide pairs that are interchangeable without altering the amino acid are used in the numerator of equation (3). For example, consider the codon AAA, which encodes the amino acid Lys. If we are interested in determining πS and πN at this codon, we first note that one single-nucleotide variant at its third site is synonymous (AAG, also encoding Lys), while two single-nucleotide variants here are nonsynonymous (AAC and AAT, both encoding Asn). When estimating synonymous Di at the third position of the codon, only the products which represent no amino acid change are used in the numerator of equation (3). Thus, in this case of AAA, the products used are Ai*Gi and Ci*Ti, representing the synonymous codon pairs AAA(Lys)/AAG(Lys) and AAC(Asn)/AAT(Asn), respectively. Conversely, to compute nonsynonymous Di, only the other nucleotide pairs which do represent an amino acid change are included in the numerator of equation (3). In the case of AAA, the products used are Ai*Ci, Ai*Ti, Ci*Gi, and Gi*Ti , representing the nonsynonymous codon pairs AAA(Lys)/AAC(Asn), AAA(Lys)/AAT(Asn), AAC(Asn)/AAG(Lys), and AAG(Lys)/AAT(Asn), respectively. Thus, for the third position of the AAA codon, synonymous Di may be computed:

| (5) |

Similarly, nonsynonymous Di may be computed:

| (6) |

In the more complicated case of whole-codon comparisons, SNPs at multiple sites in the same codon are often present. The frequency of each possible codon in the population may be estimated using coverage information provided by NGS. All possible pairwise comparisons between codons (up to 2016) are considered, contributing to πS and πN following the methods of Nei and Gojobori (1986).

The method we describe allows πS and πN to be calculated for pooled haploid NGS data. To automate this method, we have developed a software platform called SNPGenie (pronounced “snip genie”), which accepts SNP reports generated by separate SNP calling bioinformatics software (see Note on Software). This approach differs from others, which estimate related population genetic parameters from aligned reads (e.g., PoPoolation; Kofler et al. 2011; Raineri et al. 2012). The SNPGenie approach is flexible in that it can be easily modified to incorporate SNP reports generated using whatever is the preferred method for calling SNPs in pools. Thus our method takes advantage of whatever SNP calling software and settings are most appropriate for the desired application. By separating the bioinformatics involved in SNP calling and evolutionary inference, our method allows more flexibility and ease in characterizing nucleotide diversity than has previously been possible. Additionally, unlike its predecessors, SNPGenie calculates: (1) dN and dS versus a reference sequence, characterizing divergence from an ancestral sequence; and (2) gene diversity at polymorphic sites, characterizing the magnitude and nature of synonymous, nonsynonymous, and ambiguous polymorphism. Finally, at a practical level, our method allows different quality measures (e.g., filtering SNPs below a minimum variant count) to be implemented without repeating the computationally intense process of SNP calling.

4. Example: Within-host Diversity of SHFV

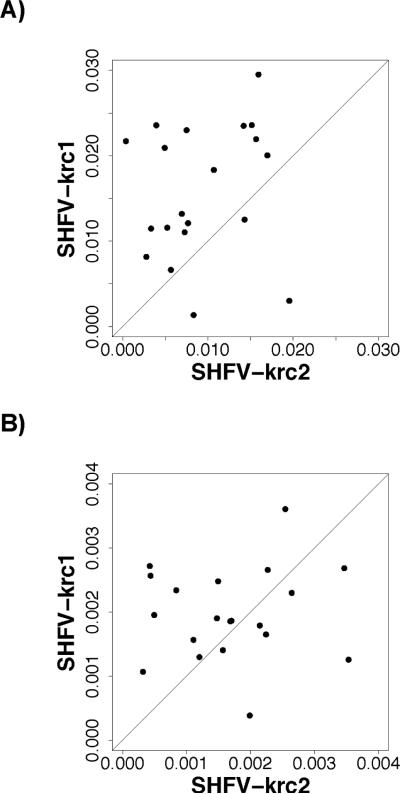

As an example of these methods, we present data on two new arteriviruses isolated from natural populations of red colobus monkeys (Procolobus rufomitratus tephrosceles) from Uganda (Bailey et al. 2014). RNA was isolated from the blood plasma of wild-caught animals, and deep sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq machine (Bailey et al. 2014). Many of the monkeys were infected by two distinct simian hemorrhagic fever viruses (SHFV), designated SHFV-krc1 and SHFV-krc2. For 20 monkeys infected by both viruses, we estimated πS and πN for all codons with non-overlapping reading frames separately for the two viral genomes (Figure 1). Nucleotide diversity was consistently higher in the SHFV-krc1 virus than the SHFV-krc2 virus. Mean πS for SHFV-krc1 was 0.0159 ± 0.00778, which was significantly greater than that for SHFV-krc2 (0.00932 ± 0.00555; 2-tailed P = 0.00353; paired t-test; Figure 1A). Mean πN for SHFV-krc1 ( 0.00197 ± 0.000726) was also greater than that for SHFV-krc2 (0.00168 ± 0.000946), but this difference was not significant (2-tailed P = 0.271; paired t-test; Figure 1B). The hypothesis that purifying selection has acted to eliminate and/or to reduce the frequency of deleterious nonsynononymous mutations in these viruses was supported by the significantly lower mean πN than mean πS in each virus (2-tailed P < 0.001 in each case; paired-t-tests).

Figure 1.

Plots of (A) πS and (B) πN in SHFV-krc1 vs. that in SHFV-krc2 from the same host red colobus monkey for all codons not overlapping multiple reading frames; in each case the line is a 45° line.

Population genetics theory predicts that neutral nucleotide diversity (reflected largely by πS) is a function of both effective population size and mutation rate per generation (Nei 1987). SHFV-krc1 showed significantly greater viremia (blood concentration of virus) estimates than SHFV-krc2, suggesting the possibility that the within-host effective population sizes of SHFV-krc1 tend to be greater than those of SHFV-krc2 (Bailey et al. 2014), which would explain the difference in πS (Figure 1A).On the other hand, it is also possible that the mutation rate per generation is higher in SHFV-krc1 than in SHFV-krc2. Comparisons of both viruses from one monkey sampled at two time points 2.5 years apart indeed suggested a higher mutation rate per unit time in SHFV-krc1 than in SHFV-krc2 (Bailey et al. 2014). However, the two viruses might still have identical mutation rates per generation if SHFV-krc1 has more generations per unit time. Resolving the relative contributions of within-host effective population size, mutation rate, and generation time to the observed difference in nucleotide diversity in these two viruses will require further study.

5. Discussion

The population biology of viruses can be studied at two distinct levels: within-hosts and across hosts. The study of within-host population biology of RNA viruses has been difficult until recently because it was necessary to infer features of a potentially very large and diverse viral population from only a small number of sequences. The availability of NGS methods that provide a much deeper picture of within-host viral diversity has a potential to change this situation dramatically. Using the methods described above we are able to obtain much more accurate estimates of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide diversity than were previously possible, thereby providing insight into viral effective population sizes and the role of natural selection.

An aspect of the fundamental biology of viruses into which these methods may provide important insights revolves around the so-called “quasispecies theory,” which models evolution in the case of infinite population sizes and high mutation rates (Eigen and Schuster 1977; Domingo 1992, 2001; Eigen 1996; Moya et al. 2000; Holmes and Moya 2002; Wilke 2005; Vignuzzi et al. 2006; Lauring and Andino 2010). Although there has been a tendency in the literature to treat quasispecies theory and population genetics as two competing paradigms, Holmes and Moya (2002, p. 461) argue that the two might best be regarded as “two research traditions” each with its own “theoretical tools to explain population dynamics.” Moreover, there are numerous overlaps between quasispecies theory and traditional population genetics. Indeed, as Wilke (2005) has shown, the quasispecies model is mathematically equivalent to the mutation-selection balance model of classical population genetics.

Rather than contrasting quasispecies theory and population genetics as a whole, it might be more accurate to highlight differences between quasispecies theory and certain predictions of the neutral theory of molecular evolution (Kimura 1983). The original quasispecies models assumed infinite population sizes, as do the deterministic models of classical population genetics, although this obviously unrealistic assumption has been relaxed by some researchers working within the quasispecies tradition (e.g., Park et al. 2010). On the other hand, the neutral theory emphasizes the importance of finite population size and genetic drift in the evolutionary process. As a consequence of genetic drift, populations are seen as inherently unstable and unpredictable in their genetic composition. By contrast, quasipecies theory tends to minimize the role of genetic drift and to predict the evolution of an equilibrium characterized by the dominance of a “cloud” of mutationally closely related genomes collectively known as a “quasispecies.”

Empirical data that have been interpreted as providing support for quasispecies theory are often ambiguous and readily subject to alternative interpretations consistent with the neutral theory. For example, in experiments with laboratory-passaged strains of vesicular stomatosis virus (VSV), a strain with a high replication rate (and thus presumed high fitness) was outcompeted by a complex viral population assumed to represent a quasispecies (de la Torre and Holland 1990). However, this same result might be predicted under the neutral theory on the principle that, when the effective population size is low, natural selection is inefficient and even high-fitness genotypes may not increase in frequency but rather may be subject to genetic drift (Kimura 1983). Since these virus populations were passaged (equivalent to “bottlenecking” in population genetic terms), they would be expected to have low effective population sizes (Hughes 2009).

Similarly, Lauring and Andino (2010) cite evidence that variants of dengue virus having a stop codon in one protein are maintained at high frequency in populations (Aaskov et al. 2006) as supporting a quasispecies model. But Aaskov et al. (2006) suggest other possible explanations for this observation that do not involve quasispecies. Since viruses in which certain proteins are defective can still be spread by “parasitizing” proteins from other viruses which co-infect the same host (Aaskov et al. 2006), selection against viruses with the stop codon may be relatively weak. Small effective population size, as a result of bottlenecks in transmission, may account for the failure of selection to remove such a mildly deleterious variant.

NGS methods can contribute to an increased understanding of within-host viral evolution, and thus to a resolution of some of the controversies raised by quasispecies theory. We will briefly discuss three types of relevant evidence to which NGS data and the aforementioned methods of analysis can contribute:

Synonymous and Nonsynonymous Polymorphism

Jenkins et al. (2001) have argued that a pattern whereby πS exceeds πN in VSV is evidence against the quasispecies theory because it implies that numerous synonymous mutations are neutral or nearly so, whereas the accumulation of neutral polymorphism is not predicted by the quasispecies model. However, the sequences which Jenkins et al. (2001) analyzed were sampled from numerous different hosts; thus, because they did not represent within-host populations, the relevance of these data to the quasispecies model of within-host virus evolution might be questioned. Sanger sequencing of within-host populations of viruses has shown a pattern whereby πS substantially exceeds πN in a variety of viruses (Hughes et al. 2005; Callendret et al. 2011; Li et al. 2001). Similar patterns have been seen in studies using NGS data (Hughes et al. 2012; Lauck et al. 2012; Wilker et al. 2013; Bailey et al. 2014). Further studies using NGS methods will make it possible to estimate the relative magnitude of synonymous and nonsynonymous polymorphism for within-host virus populations, and thus to assess the role of neutral mutations and genetic drift in within-host viral evolution.

Increase in Polymorphism over Time

The neutral theory predicts that most polymorphism in natural populations is selectively neutral or nearly so. Thus, in the absence of perturbing factors such as radical changes in the selective regime or population bottlenecks, neutral polymorphism will accumulate over time as a consequence of mutation. The quasispecies theory, by contrast, predicts that an equilibrium state will develop after which polymorphism will not increase. So far relatively few studies have examined within-host viral polymorphism at several time points over the course of infection; however, several studies using Sanger sequencing (Callendret et al. 2011; Li et al. 2011) have provided evidence that polymorphism – particularly synonymous polymorphism – increases over time, as predicted by the neutral theory. Particularly interesting were data showing a steady increase over time of within-host viral πS in human patients, raging from 2 to 38 years post-infection with HCV (Li et al. 2011). It is important to test for the generality of this pattern across different RNA virus species. Because NGS methods provide the potential for examining genome-wide viral polymorphism at different time points over the course of infection, these methods seem particularly well designed for addressing this question.

The Impact of Effective Population Size

According to the neutral theory, the extent of sequence polymorphism maintained in a population should be correlated with its effective population size, while quasispecies theory argues that within-host populations of RNA viruses are so large that effective population size can be ignored. Results such as those of Bailey et al. (2014) support the neutral theory since they suggest a correlation between nucleotide diversity and viral load (viremia), which may reflect viral population size. The correlation between virus nucleotide diversity and viral load requires further testing in a variety of viruses.

In addition to the potential utility of NGS analyses in addressing theoretical debates regarding quasispecies theory, the approaches described here are useful in studying a number of other questions regarding within-host virus evolution. They can provide evidence regarding positive selection favoring new viral mutants, including those that confer escape from host immune recognition mechanisms (Hughes et al. 2012); those that confer resistance to anti-viral drugs; and those that are favored because they better adapt the virus to a new host species (Wilker et al. 2013).

6. Note on Software

We have developed and implemented a software platform called SNPGenie (Wilker et al. 2013; Bailey et al. 2014) for analyzing synonymous and nonsynonymous polymorphism in pooled NGS samples. SNPGenie in written in Perl for Unix operating systems, but is available for Windows users in an executable form. It accepts SNP reports in either Geneious or CLC Genomics Workbench standard formats, but is amenable to inclusion of others. It also requires a reference fasta file(s) and gene annotations in gene transfer format (gtf). SNPGenie makes several advances over previous approaches (Kofler et al. 2011; Raineri et al. 2012). First, synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide diversities are estimated using approaches that consider SNPs in isolation or in the context of other SNPs. For the latter, when multiple SNPs occur within the same codon, all possible evolutionary paths between the codons are considered by the methods of Nei and Gojobori (1986). Because they contain no synonymous sites, START and STOP codons do not contribute to synonymous diversity. SNPGenie also uses the Nei-Gojobori (1986) method and considers SNP frequencies when determining the number of synonymous and nonsynonymous sites in a codon. This provides much more accurate estimates of nucleotide diversity than possible when estimating site numbers using the reference sequence in isolation.

Additionally, unlike its predecessors, SNPGenie calculates mean dS and mean dN versus a reference sequence. In studies of within-host virus evolution, estimating these quantities can be useful in cases where one knows the ancestral or inoculum sequences; e.g., in cases of experimental infection with a known inoculum (Hughes et al. 2010). In addition, SNPGenie calculates gene diversity at individual polymorphic sites (Hughes et al. 2003; Knapp et al. 2011). Finally, sliding window analyses are performed for each gene product according to a user-specified number of codons. An important practical point is that our method allows different quality measures (e.g., filtering SNPs below a minimum variant count) to be implemented without repeating the computationally intense process of SNP calling. Alternative SNPGenie scripts for Geneious and CLC are available at ww2.biol.sc.edu/~austin/.

Next generation sequencing (NGS) can yield insights into within-host viral evolution

Synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide diversity can be estimated from NGS data

Nucleotide diversity estimates can provide insights into population structure and natural selection

The data can illuminate both practical and theoretical issues regarding the evolution of viruses during infection

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grant AI077376 to David H. O'Connor and A.L.H.; by NIH grant AI096882 to Jonathan Honegger, Christopher Walker, and A.L.H.; and by NSF Graduate Research Fellowship DGE-0929297 and a University of South Carolina Presidential Fellowship to C.W.N.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aaskov J, Buzacott K, Thu HM, Lowry K, Holmes EC. Long-term transmission of defective RNA viruses in humans and Aedes mosquitoes. Science. 2006;311:236–238. doi: 10.1126/science.1115030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey AL, Lauck M, Weiler A, Sibley SD, Dinis J, Bergman Z, Nelson CW, Correll M, Gleicher M, Hyeroba D, Tumukunde A, Weny G, Chapman C, Kuhn J, Hughes AL, Friedrich TC, Goldberg TL, O'Connor DH. High genetic diversity and adaptive potential of two simian hemorrhagic fever viruses in a wild primate populations. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e90714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerenwinkel N, Zagordi O. Ultra-deep sequencing for the analysis of viral populations. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011;1:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bimber BN, Dudley DM, Lauck M, Becker EA, Chin EN, Lank SM, Grunenwald HL, Caruccio NC, Maffit M, Wilson NA, Reed JS, Sosman JM, Tarosso LF, Sanabani S, Kallas EG, Hughes AL, O'Connor DH. Whole genome characterization of HIV/SIV intrahost diversity by ultradeep pyrosequencing. J. Virol. 2010;84:12087–12092. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01378-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callendret B, Eccleston HB, Heksch R, Hasselschwert DL, Purcell RH, Hughes AL, Walker CM. Transmission of clonal hepatitis C virus genomes reveals dominant but transitory role for CD8+T cells in early viral evolution. J. Virol. 2011;85:11833–11845. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02654-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon NA, Donlin MJ, Fan X, Aurora R, Tavis JE, Virahep-C Study Group Hepatitis C virus diversity and evolution in the full open-reading frame during antiviral therapy. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(5):e2123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre JC, Holland JJ. RNA quasispecies populations can suppress vastly superior mutant progeny. J. Virol. 64:6278–6281. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.6278-6281.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo E. Genetic variation and quasispecies. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1992;2:61–63. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80323-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo E. Quasispecies theory in virology. J. Virol. 2002;76:463–465. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.1.463-465.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigen M. On the nature of viral quasispecies. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:216–218. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)20011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigen M, Schuster P. A principle of natural self-organization. Naturwissenschaften. 1977;64:541–546. doi: 10.1007/BF00450633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DT, O'Connor DH, Jing P, Dzuris JL, Sidney J, Da Silva J, Allen TM, Horton H, Venham JE, Rudersdorf RA, Vogel T, Pauza CD, Bontrop RE, DeMars R, Sette A, Hughes AL, Watkins DI. Virus-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses select for amino-acid variation in simian immunodeficiency virus Env and Nef. Nature Medicine. 1999;5:1270–1276. doi: 10.1038/15224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futschik A, Schlötterer C. The next generation of molecular markers from massively parallel sequencing of pooled DNA samples. Genetics. 2010;186:208–218. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.114397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedskog C, Mild M, Jernberg J, Sherwood E, Bratt G, Leitner T, Lundeberg J, Andersson B, Albert J. Dynamics of HIV-1 quasispecies during antiviral treatment dissected using ultra-deep pyrosequencing. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(7):e11345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EC, Moya A. Is the quasispecies concept relevant to RNA viruses? J. Virol. 2002;76:460–462. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.1.460-462.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL. Adaptive Evolution of Genes and Genomes. Oxford University Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL, Packer B, Welsch R, Bergen AW, Chanock SJ, Yeager M. Widespread purifying selection at polymorphic sites in human protein-coding loci. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:15754–15757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536718100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL. Relaxation of purifying selection on live attenuated vaccine strains of the family Paramyxoviridae. Vaccine. 2009;27:1685–1690. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL, Hughes MA. Patterns of nucleotide difference in overlapping and non-overlapping reading frames of papillomavirus genomes. Virus Research. 2005;113:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL, Hughes MA. Patterns of nucleotide difference in overlapping and non-overlapping reading frames of papillomavirus genomes. Virus Research. 2005;113:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL, Westover K, da Silva J, O'Connor DH, Watkins DI. Simultaneous positive and purifying selection on overlapping reading frames of the tat and vpr genes of simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 2001;75:7666–7672. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.17.7966-7972.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL, Piontkivska H, Krebs KC, O'Connor DH, Watkins DI. Within-host evolution of CD8+-TL epitopes encoded by overlapping and non-overlapping reading frames of simian immunodeficiency virus. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(Suppl. 3):iii39–iii44. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL, O'Connor S, Dudley DM, Burwitz BJ, Bimber BN, O'Connor D. Dynamics of haplotype frequency change in a CD8+TL epitope of simian immunodeficiency virus. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2010;10:555–560. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL, Becker EA, Lauck M, Karl JA, Braasch AT, O'Connor DH, O'Connor SL. SIV genome-wide pyrosequencing provides a comprehensive and unbiased view of variation within and outside CD8 T lymphocyte epitopes. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10):e47818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins GM, Worobey M, Woelk CH, Holmes HC. Evidence for nonquasispecies evolution of RNA viruses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2001;18:987–994. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. The Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp EW, Irausquin SJ, Friedman R, Hughes AL. PolyAna: analyzing synonymous and nonsynonymous polymorphic sites. Conservation Genet. Resources. 2011;3:429–431. doi: 10.1007/s12686-010-9372-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofler R, Orozco-terWengel P, De Maio N, Pandey RV, Nolte V, Futschik A, Kosiol C, Schlötterer C. PoPoolation: a toolbox for population genetic analysis of next generation sequencing data from pooled individuals. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(1):e15925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauck M, Alvarado-Mora MV, Becker EA, Bhattacharya D, Striker R, Hughes AL, Carrilho FJ, O'Connor DH, Rebello Pinho JR. Analysis of hepatitis C virus intra-host diversity across the coding region by ultra-deep pyrosequencing. J. Virol. 2012;86:3952–3960. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06627-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauring AS, Andino R. Quasispecies theory and the behavior of RNA viruses. PLoS Pathogens. 2010;6(7):e1001005. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le T, Chiarella J, Simen BB, Hanczaruk B, Egholm M, Landry ML, Diekhaus K, Rosen MI, Kozal MJ. Low abundance HIV drug-resistant viral variants in treatment-experienced persons correlate with historical antiretroviral use. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(6):e6079. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Hughes AL, Bano N, McArdle S, Livingston S, Deubner H, McMahon BJ, Townshend-Bulson L, McMahan R, Rosen HR, Gretch DR. Genetic diversity of near genome-wide hepatitis C virus sequences during chronic infection: evidence for protein structural conservation over time. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(5):e19562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WH. Molecular Evolution. Sinauer; Sunderland MA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Moya A, Elena SF, Bracho A, Miralles R, Barrio E. The evolution of RNA viruses: a population genetics view. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6967–6973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.6967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudd PA, Ericsen AJ, Burwitz BJ, Wilson NA, O'Connor DH, Hughes AL, Watkins DI. Escape from CD8+ T cell responses in Mamu-B*00801+ macaques differentiates progressors from elite controllers. J. Immunol. 2012;188:3364–3370. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M. Molecular evolutionary genetics. Columbia University Press; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Nei M, Gojobori T. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1986;3:418–426. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M, Kumar S. Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor SL, Weinfurter J, Chin EN, Budde ML, Gostick E, Correll M, Gleicher M, Hughes AL, Price DA, Friedrich TC, O'Connor DH. Conditional CD8+ T cell escape during simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Virol. 2012;85:605–609. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05511-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J-M, Muñoz E, Deem MW. Quasispecies theory for finite populations. Phys. Rev. E. 2010;81:011902. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.81.011902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raineri E, Ferretii L, Esteve-Codina A, Nevado B, Heath S, Pérez-Enciso M. SNP calling by sequencing pooled samples. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:239. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozera G, Abbate I, Bruselles A, Vlassi C, D'Offizi G, Narciso P, Chillemi G, Prosperi M, Ippolito G, Capobianchi MR. Massively parallel pyrosequencing highlights minority variants in the HIV-1 env quasispecies deriving from lymphomonocyte sub-populations. Retrovirology. 2009;6:15. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignuzzi M, Stone JK, Arnold JL, Cameron CE, Andino R. Quasispecies diversity determines pathogenesis through cooperative interactions in a viral population. Nature. 2006;439:233–348. doi: 10.1038/nature04388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh AD, Bimber BN, Das A, Piaskowski SM, Rakasz EG, Bean AT, Mudd PA, Ericksen AJ, Wilson NA, Hughes AL, O'Connor DH, Maness NJ. Acute phase CD8+ T lymphocytes against alternate reading frame epitopes select for rapid viral escape during SIV infection. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e61383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Mitsuya Y, Gharizadeh B, Ronaghi M, Shafer RW. Characterization of mutation spectra with ultra-deep pyrosequencing: application to HIV-1 drug resistance. Genome Res. 2010a;17:1195–1201. doi: 10.1101/gr.6468307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GP, Sherrill-Mix SA, Chang K-M, Quince C, Bushman FD. Hepatitis C virus transmission bottlenecks analyzed by deep sequencing. J. Virol. 2010b;84:6218–6228. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02271-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke CO. Quasispecies theory in the context of population genetics. BMC Evol. Biol. 2005;2005;5:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilker P, Dinis JM, Starrett G, Imai M, Hatta M, Nelson CW, O'Connor DH, Hughes AL, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y, Friedrich TC. Selection on hemagglutinin imposes a bottleneck during mammalian transmission of reassortant H5N1 influenza viruses. Nature Comm. 2013;4:2636. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CF, Morelli MJ, Thébaud G, Knowles NJ, Herzyk P, Paton DJ, Haydon DT, King DP. Beyond the consensus: dissecting within-host viral population diversity of foot-and-mouth disease virus by using next-generation genome sequencing. J. Virol. 2011;85:2266–2275. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01396-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]