Abstract

The production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is an unavoidable consequence of oxygenic photosynthesis. Singlet oxygen (1O2) is a highly reactive species to which has been attributed a major destructive role during the execution of ROS-induced cell death in photosynthetic tissues exposed to excess light. The study of the specific biological activity of 1O2 in plants has been hindered by its high reactivity and short lifetime, the concurrent production of other ROS under photooxidative stress, and limited in vivo detection methods. However, during the last 15 years, the isolation and characterization of two 1O2-overproducing mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana, flu and ch1, has allowed the identification of genetically controlled 1O2 cell death pathways and a 1O2 acclimation pathway that are triggered at sub-cytotoxic concentrations of 1O2. The study of flu has revealed the control of cell death by the plastid proteins EXECUTER (EX)1 and EX2. In ch1, oxidized derivatives of β-carotene, such as β-cyclocitral and dihydroactinidiolide, have been identified as important upstream messengers in the 1O2 signaling pathway that leads to stress acclimation. In both the flu and ch1 mutants, phytohormones act as important promoters or inhibitors of cell death. In particular, jasmonate has emerged as a key player in the decision between acclimation and cell death in response to 1O2. Although the flu and ch1 mutants show many similarities, especially regarding their gene expression profiles, key differences, such as EXECUTER-independent cell death in ch1, have also been observed and will need further investigation to be fully understood.

Keywords: singlet oxygen, oxidative stress, cell death, acclimation, EXECUTER, β-cyclocitral, phytohormones, oxylipins

INTRODUCTION

Singlet oxygen (1O2) is an unavoidable byproduct of oxygenic photosynthesis. This reactive oxygen species (ROS) is produced in energy transfer reactions from the excited triplet state of chlorophyll molecules or their precursors to molecular oxygen. 1O2 is highly reactive and engages readily with a variety of biomolecules, especially those containing double bonds (Triantaphylidès and Havaux, 2009), and results in reduced photosynthetic efficiency and ultimately cell death. 1O2 is believed to be the main ROS produced in the chloroplasts under stress and excess light, playing a major destructive role during the execution of ROS-induced cell death in leaf tissues (Triantaphylidès et al., 2008). Plants have developed various scavenging systems to protect themselves against the toxic effects of 1O2. Carotenoids, tocopherols and plastoquinones which are present in the thylakoid membranes are thought to play an essential role in quenching 1O2 (Krieger-Liszkay et al., 2008; Triantaphylidès and Havaux, 2009). Other scavengers such as ubiquinol, ascorbate, and glutathione may also quench 1O2.

While the intracellular signaling functions of the long-lived ROS hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and its implication in the regulation of cell death have been established for some time (Levine et al., 1994; Thordal-Christensen et al., 1997), a similar function for 1O2 has only been recognized more recently in plants (op den Camp et al., 2003; Wagner et al., 2004). This delayed knowledge stems from the fact that the study of the specific biological activity of 1O2 in plants is hampered, firstly, by the high reactivity and short lifetime of this ROS [∼4 μs in water (Wilkinson et al., 1995), likely lower than 0.5–1 μs in plant cells (Bisby et al., 1999; Redmond and Kochevar, 2006; Li et al., 2012; Telfer, 2014)], and, secondly, by the concurrent production of other ROS under photooxidative stress. Nevertheless, our comprehension of the cellular responses to 1O2 in plants has dramatically progressed during the last decade, thanks to the use of Arabidopsis thaliana (hereafter, Arabidopsis) mutants characterized by the conditional accumulation of 1O2 within the chloroplast. This mutant approach has revealed that, besides its direct toxicity, 1O2 can also function as a signal molecule (Kim et al., 2008). Depending on the levels of 1O2 production induced by light in these mutants, the 1O2-triggered signaling pathway was found to lead to different cell death responses or to an acclimation process, with phytohormones appearing to be major players in the orientation of the 1O2 signaling pathway toward a particular response. The present review summarizes the main findings on these 1O2-induced cell death and acclimation mechanisms and their control by phytohormones.

GENETICALLY CONTROLLED 1O2-TRIGGERED CELL DEATH IN Arabidopsis: LEARNING FROM THE flu MUTANT

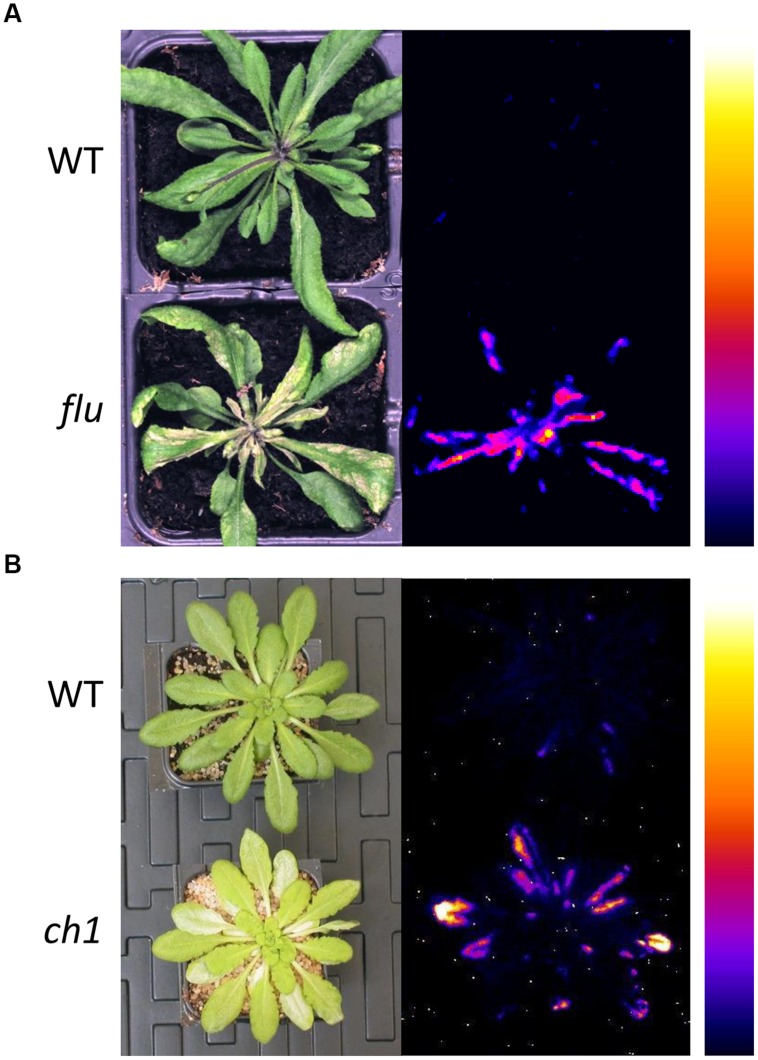

A major breakthrough in understanding the intracellular signaling function of 1O2 was the isolation and characterization of the conditional fluorescent (flu) mutant of Arabidopsis, which is defective in the nuclear-encoded FLU protein involved in the negative feedback control of the Mg2+ branch of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis (Meskauskiene et al., 2001; Meskauskiene and Apel, 2002). In contrast to wild-type plants, flu plants are no longer able to restrict the synthesis of protochlorophyllide (Pchlide) in the dark. As a consequence, free Pchlide accumulates in the dark and then acts as a photosensitizer upon re-illumination, generating 1O2 in a rapid (and probably transient) manner within the chloroplasts (Figure 1). The flu mutant has two other important properties. First, flu plants under continuous light, where Pchlide is immediately photo-reduced to chlorophyllide and hence does not accumulate, have a wild-type phenotype. Second, the amount of 1O2 generated is proportional to the amount of Pchlide and hence to the extent of the dark period. Therefore, the conditional flu mutant is a powerful tool for the generation of different quantities of 1O2 in photosynthetic tissues in a noninvasive and controlled manner. This makes it possible to study the stress response triggered by the release of a specific quantity of 1O2 inside plastids simply by growing the plants under continuous light till they reach the developmental stage of interest, transferring them to the dark for a defined time period, and then re-illuminating them.

FIGURE 1.

Photosensitivity of the 1O2-overproducing Arabidopsis mutants, flu and ch1. (A) Wild-type (WT) and flu mutant plants after an 8 h dark/light transition, showing leaf damage (2 days after the dark-to-light shift, left) and lipid peroxidation as measured by autoluminescence imaging (2 h after the dark-to-light shift, right). (B) WT and ch1 mutant plants after high light stress (1000 μmol photons m-2 s-1 for 2 days), showing leaf bleaching (left) and lipid peroxidative damage (right). No luminescence and no leaf damages were detected in WT and the mutant plants before the light treatments. The color palette on the right indicates the intensity of the luminescence signal from low (dark blue) to high (white). The signal intensity is indicative of the amount of lipid peroxides present in the sample (Birtic et al., 2011). Adapted from Ramel et al. (2013a) (Copyright American Society of Plant Biologists, http://www.plantcell.org) and completed.

In this way, the release of 1O2 during re-illumination of flu plants grown under continuous light and transferred to the dark for 8 h was initially shown to result in a rapid induction of specific sets of nuclear genes that were not activated by other treatments generating different ROS inside plastids (op den Camp et al., 2003; Gadjev et al., 2006; Laloi et al., 2006). In addition, two obvious stress responses were observed in flu plants following the release of 1O2: a transient inhibition of growth almost immediately after the beginning of re-illumination, and a cell death response. Quite unexpectedly, the growth arrest and cell death responses in the flu mutant were found to result from a genetic program that involves the EXECUTER proteins (EX1 and EX2), rather than from the direct toxicity of 1O2 (Wagner et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2007). The EXECUTER pathway also promoted cell death in wild-type plants treated with DCMU (3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea) (Wagner et al., 2004), a herbicide that blocks photosynthetic electron transport at the level of the photosystem II (PSII) primary quinone electron acceptor, thus leading to the increased production of 1O2 in PSII reaction centers (Fufezan et al., 2002). Cytological changes that follow the onset of 1O2 production have been recently shown to include the sequential rapid loss of chloroplast integrity that precedes the rupture of the central vacuole and the final collapse of the cell (Kim et al., 2012). Inactivation of the two plastid proteins EXECUTER in the flu mutant abrogates these responses, indicating that disintegration of chloroplasts is due to EX-dependent signaling rather than 1O2 directly (Kim et al., 2012). Interestingly, it was shown that the initial light-dependent release of 1O2 was not sufficient to trigger the onset of cell death, but had to act together with a second concurrent blue light reaction that requires the activation of the UVA/blue light- absorbing photoreceptor CRY1 (Danon et al., 2006).

CELL DEATH-PROMOTING AND -INHIBITORY SIGNALS IN flu

Several genes that are up-regulated after the release of 1O2 in the flu mutant encode proteins involved in the biosynthesis or signaling of the phytohormones ethylene (ET), salicylic acid (SA), and jasmonic acid (JA), suggesting that these phytohormones could be involved in triggering cell death. This hypothesis is further supported by the increased concentrations of oxylipins [12-oxo-phytodienoic acid (OPDA), dinor-OPDA (dnOPDA), and JA] in flu soon after re-illumination. The oxylipin increase was followed by a slower increase in SA, with variations depending on the developmental stage (Danon et al., 2005; Ochsenbein et al., 2006; Figure 2). The possible involvement of these phytohormones in regulating cell death was tested by combining genetic and pharmacological approaches (Danon et al., 2005). flu mutant seedlings expressing the NahG transgene, which encodes a salicylate hydroxylase that converts SA to catechol, were partially protected from the death provoked by the release of 1O2, suggesting a requirement for SA in this process. However, a role for the possibly increased levels of catechol in reducing the susceptibility was not completely excluded (van Wees and Glazebrook, 2003; Danon et al., 2005). A similar partial protection from cell death was found when ET biosynthesis was blocked in the flu mutant by the addition of L-aminoethoxyvinylglycine (AVG), a potent inhibitor of 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) synthase. These treatments were additive because flu NahG plants grown on a medium containing AVG were almost fully protected from cell death. This suggests that there is a synergistic interaction between the SA and ET signaling pathways during the regulation of cell death induced by 1O2 in flu (Danon et al., 2005).

FIGURE 2.

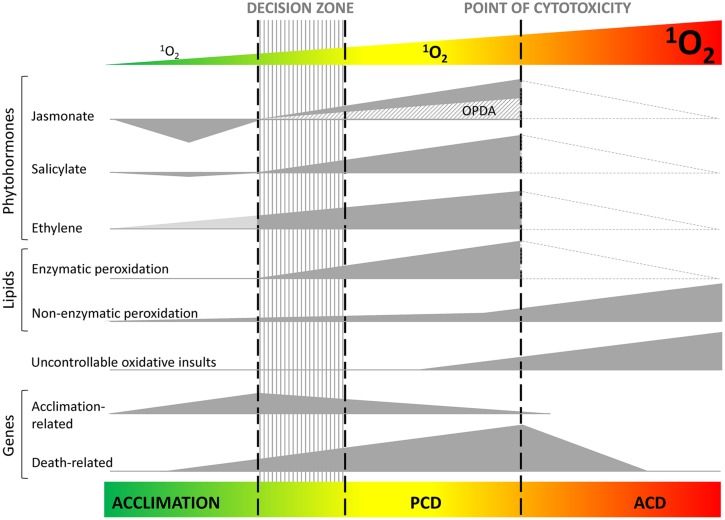

A model for the cellular responses to different 1O2 levels. Depending on the level of 1O2, the plant cell might trigger an acclimation response or a programmed cell death (PCD) program, or, in case of extreme 1O2 production, will succumb in a completely uncontrollable manner to the so-called ‘accidental cell death’ (ACD), due to a general oxidation that leads to the loss of structural integrity. PCD and acclimation, which are both initiated by genetically encoded machinery, are controlled by the phytohormones jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA), and ethylene (ET). JA, SA, and ET seem to work as PCD-promoting signals, while the JA precursor OPDA (and dnOPDA) might counteract the JA-effect and work as inhibitory signals. JA seems to play a central role in the decision between acclimation and PCD. Evidence suggests that 1O2 production sites, production rates and production times will influence this model. The dotted lines in the ACD zone indicate predicted changes in phytohormone concentrations which still need to be substantiated by experimental data.

The possible role of oxylipins in the 1O2 cell death was investigated by crossing flu with the JA-depleted mutant opr3 and with the JA-, OPDA-, and dnOPDA-depleted dde2-2 mutant defective in the ALLENE OXIDE SYNTHASE gene. The analysis of cell death in the double mutant lines, in combination with or without the addition of exogenous JA, revealed that, in contrast to the JA-induced suppression of superoxide/H2O2-dependent cell death, JA promotes the 1O2-mediated cell death reaction. Other oxylipins, most likely OPDA/dnOPDA, were found to antagonize the death-promoting activity of JA (Danon et al., 2005; Figure 2).

Other ROS seem to have an inhibitory effect on 1O2-triggered cell death, as revealed in flu plants overexpressing the thylakoid-bound ascorbate peroxidase (tAPX), an H2O2-scavenging enzyme (Murgia et al., 2004). In flu overexpressing tAPX, the intensity of 1O2-mediated cell death was increased when compared with the flu line, suggesting that H2O2 either directly or indirectly suppresses 1O2-triggered cell death (Laloi et al., 2007). The inhibitory effect of H2O2 may explain why, in wild-type plants exposed to photooxidative stress conditions that trigger the simultaneous production of 1O2 and H2O2, cell death is delayed by several days from the onset of the light stress. In contrast, the generation of 1O2 in flu occurs without a concomitant production of H2O2 and is rapidly followed by cell death (Kim et al., 2012). In the microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, H2O2 production induced by high light treatment was shown to promote carotenoid synthesis, thus enhancing 1O2 scavenging ability and hence delaying photooxidative damage and cell death (Chang et al., 2013). This delay appears to be important for allowing the plant enough time to activate adaptive responses before initiating a cell death program if cellular homeostasis cannot be restored. The antagonistic effect of H2O2 on 1O2-triggered cell death might thus contribute to the overall robustness of wild-type plants exposed to photooxidative stress conditions. Therefore, the relative amount of different ROS, rather than the concentration of one particular ROS, seems to determine the activation of either a stress defense or cell death programs. This hypothesis is developed in greater detail in the context of leaf senescence by Sabater and Martín (2013) in this Research Topic.

1O2-TRIGGERED ACCIDENTAL CELL DEATH IN flu

The flu mutant was isolated and first characterized during a genetic screen for etiolated mutant seedlings that are no longer able to restrict the accumulation of Pchlide in the dark and hence emit strong red Pchlide fluorescence when exposed to blue light. In etiolated seedlings, introduction of the ex1 mutation does not suppress seedling lethality of the flu mutation. The ineffectiveness of the ex1 mutation under these conditions has been attributed to the fact that flu and flu ex1 etiolated seedlings accumulate about four times more Pchlide than seedlings grown in continuous light and transferred to the dark for 8 h, which are the initial light conditions under which the ex1 mutation was shown to suppress cell death and growth inhibition (Wagner et al., 2004; Przybyla et al., 2008). Therefore, flu plants exposed to an 8 h dark period then re-illuminated appear to produce a relatively low level of 1O2 which has limited cytotoxic effects, but which is nevertheless able to trigger a genetically controlled cell death program that is regulated by the EXECUTER proteins. Conversely, etiolated flu seedlings transferred to light generate a high level of 1O2 that is cytotoxic and causes irreversible damage to cellular components (Przybyla et al., 2008). Thus, at least two types of cell death can be triggered by 1O2 in flu: cells exposed to very high levels of 1O2 succumb in a EXECUTER-independent and uncontrollable manner, a process generally referred to as “accidental cell death” (ACD; van Doorn et al., 2011; Galluzzi et al., 2015); alternatively, in cells exposed to a lower production of 1O2 inside plastids, a programmed cell death (PCD) is initiated that involves the genetic control by EXECUTER proteins. Both types of cell death may coexist at the level of a tissue, organ or the whole plant, significantly complicating the identification of reliable molecular markers for cell death type.

Measurements of oxylipins, the oxidation products of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), further support the concept of two types of 1O2-triggered cell death. Etiolated flu seedlings transferred to light accumulate large amounts of non-enzymatically formed oxylipins, the hydroxyoctadecadienoic acids (HODE) 10-HODE and 12-HODE and the hydroxyoctadecatrienoic acids 10-HOTE and 15-HOTE. This indicates that under these extreme conditions the toxic effects of 1O2 prevail (Przybyla et al., 2008). Interestingly, 10-HOTE and 15-HOTE, which are specific products of 1O2-mediated PUFA oxidation, also accumulate in wild-type plants exposed to simultaneous high light and cold conditions (Havaux et al., 2009). This suggests that 1O2 is the major ROS responsible for lipid peroxidation under these conditions (Triantaphylidès et al., 2008). In contrast to etiolated flu seedling, flu plants kept in the dark for 8 h then re-illuminated accumulate enzymatically produced oxylipins, such as 13-HOTE, 13-HODE, OPDA, and JA; the products of non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation are not detected (Przybyla et al., 2008).

The discovery of at least two different types of 1O2-triggered cell death in the flu mutant raises the question of whether 1O2 levels lower than those that trigger genetically controlled cell death could activate an acclimation response. The characterization of another 1O2–producing mutant, ch1, has allowed us to answer this question.

THE Arabidopsis ch1 MUTANT, AN ALTERNATIVE MODEL TO flu

Impairment of the CAO gene, encoding chlorophyll a oxygenase, in the Arabidopsis chlorina1 (ch1) mutant results in the absence of chlorophyll b and in a pale-green phenotype (Espineda et al., 1999). Because functional PSII antennae cannot assemble in the absence of chlorophyll b (Plumley and Schmidt, 1987), the ch1 mutant is completely deficient in functional light-harvesting antenna complex of PSII (LHCII; Havaux et al., 2007). The only PSII antenna protein detected in significant amounts in ch1 is Lhcb5, but this protein is not assembled with pigments and is therefore not functional in this mutant (Havaux et al., 2007; Figure 1). Thus, PSII is composed solely of its reaction center core (with the internal antennae) in the leaves of ch1. These alterations have relatively little effect on photosynthetic electron flow at high photon flux densities (PFDs; Havaux et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2009; Ramel et al., 2013a). Loss of the normal structural architecture around the PSII reaction centers in chlorophyll b–less plant mutants has significant effects on the functionality of the PSII complexes, including loss of non-photochemical energy quenching (NPQ), impaired oxidizing side of PSII, and reduced grana stacking (Havaux and Tardy, 1997; Kim et al., 2009). LHCI antennae are less dependent on chlorophyll b for assembly than LHCIIs and, consequently, the PSI units retain part of their LHCIs in ch1 mutant leaves (Havaux et al., 2007; Takabayashi et al., 2011).

The ch1 mutant was found to be highly photosensitive, exhibiting leaf damage and cell death under light conditions (1000 μmol photons m-2 s-1 for 2 days) that had very limited effects on wild-type leaves (Havaux et al., 2007; Figure 1). This effect is attributable to an increased release of 1O2 from the ‘naked’ PSII centers in the absence of the protective mechanisms associated with the light-harvesting system, such as non-photochemical energy quenching (NPQ). Accordingly, inhibition of NPQ in the Arabidopsis npq4 mutant has been reported to increase the oxidation of β-carotene by 1O2 in the PSII reaction centers (Ramel et al., 2012a). The enhanced formation of 1O2 in ch1 was confirmed by measuring 1O2 in leaves using 1O2-specific flu probes (Dall’Osto et al., 2010; Ramel et al., 2013a) and lipid oxidation markers (Triantaphylidès et al., 2008), or in thylakoids using spin probes and EPR spectroscopy (Ramel et al., 2013a). Moreover, a good correlation was found between the transcriptomic profiles of the ch1 and flu mutants, supporting the fact that a 1O2 signaling pathway is activated in the ch1 leaves under high light stress. However, important differences were observed between the two mutants. First, cell death in ch1 is not dependent on the EXECUTER proteins (Ramel et al., 2013a). Second, the increased production of 1O2 in the ch1 mutant occurs in the main natural production site, the PSII reaction center (Krieger-Liszkay et al., 2008; Telfer, 2014), while in flu 1O2 is produced from the membrane-bound chlorophyll precursor Pchlide in the absence of PSII over-excitation (op den Camp et al., 2003; Przybyla et al., 2008). In addition, the flu mutant must be grown in continuous light to avoid accumulation of Pchlide, while the ch1 mutant does not require any particular light regime.

1O2-TRIGGERED ACCLIMATION IN ch1

By playing with the light conditions, it was found that ch1 plants are able to acclimate to 1O2. Pre-exposure of ch1 plants to a moderately elevated PFD, which induces a moderate and controlled production of 1O2, rendered the plants resistant to high light stress conditions that induced lipid peroxidation, loss of chlorophyll and PSII inhibition in non-pretreated ch1 plants (Ramel et al., 2013a). This acclimation phenomenon was not associated with a reduction in the formation of 1O2 in the PSII centers, indicating a true acclimation phenomenon. Gene responses to 1O2 that do not lead to cell death were previously reported in the lut2 npq1 double mutant of Arabidopsis deficient in two 1O2 quenchers (Alboresi et al., 2011). In this mutant 1O2 formation was associated with the induction of genes whose function is to protect chloroplasts against the damaging effect of ROS. A 1O2-mediated stress acclimation phenomenon has also been reported more recently in wild-type Arabidopsis (Kim and Apel, 2013; Zhang et al., 2014). In addition, Arabidopsis cell suspensions exposed to high light display gene responses that very much resemble the gene expression profile induced in the flu mutant by 1O2, but again this occurs in the absence of cell death (González-Pérez et al., 2011).

Acclimation and increased resistance to photooxidative damage in ch1 were accompanied by a strong downregulation of the JA pathway (Ramel et al., 2013a; Figure 2); almost all genes of the JA pathway were downregulated during the acclimation treatment. Moreover, mutational suppression of JA synthesis led to constitutive phototolerance in Arabidopsis leaves: a double mutant generated by crossing the ch1 mutant with the jasmonate-deficient mutant dde2 was found to be tolerant to light stress conditions that induced severe photooxidative damage in the ch1 single mutant (Ramel et al., 2013b). Conversely, photodamage in non-acclimated plants was correlated with JA accumulation. Importantly, exogenous applications of methyl-JA were observed to cancel the acclimation response. These results allow us to refine our understanding of the interaction between the 1O2 signaling and JA pathways that was revealed earlier in the flu mutant. JA appears to act as a ‘decision maker’ between cell death and acclimation, with high concentrations of this phytohormone favoring the onset of cell death (Ramel et al., 2013b). In contrast, the strong inhibition of JA biosynthesis, as observed in ch1 leaves during acclimation to 1O2, prevents cell death and allows the initiation of cellular defense mechanisms (Figure 2). In other words, JA appears to function as a cell death-promoting phytohormone in the response of plants to high light stress. This is consistent with numerous molecular genetic studies that have provided evidence for the involvement of JAs in the regulation of cell death program under various environmental stress conditions (Reymond and Farmer, 1998; Balbi and Devoto, 2008; Reinbothe et al., 2009; Avanci et al., 2010). Whether other oxylipins such as OPDA and dnOPDA could antagonize the activities of JA during high light stress and/or acclimation in ch1 remains elusive since the concentration of OPDA did not seem to be affected by the treatments (Ramel et al., 2013a).

The role of JAs in plant cell death regulation involves interactions with other signal molecules such as SA and ET (Reymond and Farmer, 1998; Reinbothe et al., 2009; Ballaré, 2011). The close correlation between JA levels and sensitivity to 1O2 was not observed for SA, which exhibited little change during photooxidative stress in ch1 mutant plants, unlike in the flu mutant (Ramel et al., 2013a). On the other hand and like in flu, microarray-based transcriptomic analyses of ch1 leaves revealed the induction of a number of genes related to ET such as ACS2, ETR1, ERF1, ERF5, and ERF2, in response to increased PFDs (Ramel et al., 2013a). Interestingly, the ET-responsive element binding protein ERF72 (also known as AtEBP and RAP2.3) and the ET-inducible protein of unknown function encoded by the At2g38210 gene were found to be specifically induced during acclimation of the ch1 mutant to 1O2 stress. The ERF72 protein is involved in the ET signaling pathway, functioning as a transcription activator that regulates the expression levels of plant defense genes and confers resistance to Bax- and abiotic stress-induced plant cell death (Ogawa et al., 2007). Based on these observations, it is tempting to propose a role for ERF72 in the acclimation mechanism as a cell death suppressor. This attractive possibility is currently investigated in our laboratory using an ERF72-deficient mutant of Arabidopsis.

SECONDARY MESSENGERS OF 1O2-TRIGGERED ACCLIMATION

Recently, 1O2 oxidation products of β-carotene, such as β-cyclocitral and dihydroactinidiolide, were found to accumulate in Arabidopsis leaves under high light stress (Ramel et al., 2012b; Shumbe et al., 2014). Those carotenoid derivatives were able to induce changes in the expression of 1O2-responsive genes and to increase plant phototolerance. Since β-carotene is located in the PSII reaction center, its oxidized derivatives β-cyclocitral and dihydroactinidiolide can be considered as upstream messengers in the 1O2 signaling pathway. Although the exact mode of action of those signaling compounds is not yet known, it has been suggested that they act as reactive electrophile species (RES; Havaux, 2014). Interestingly, acclimation to 1O2 was also reported in the microalga Chlamydomonas following exposure to low, sublethal concentrations of 1O2 (Ledford et al., 2007). This acclimation process is accompanied by gene transcription changes, with the promoter of many genes containing a palindromic sequence element functioning as an electrophile response element (Fischer et al., 2012). Taken together, these results strongly support the involvement of lipid and/or carotenoid RES in the 1O2 signaling pathway leading to acclimation to 1O2 toxicity in photosynthetic organisms. Their mechanisms of action remain to be elucidated and constitute a major research challenge for the future. Also, the possible interactions between carotenoid RES and other metabolite retrograde signals from the chloroplasts (Estavillo et al., 2012) need to be assessed.

1O2 AND CELL DEATH IN WILD-TYPE Arabidopsis AND IN OTHER PHOTOSYNTHETIC MODELS

Data on 1O2-induced cell death in wild-type Arabidopsis and in other plant species are scarce. Compared to the ch1 and flu mutants, the responses to high light stress are more complex in the wild-type since several ROS can be produced simultaneously in the chloroplasts and several superimposing signaling pathways can be expected. In particular, it has been proposed that the 1O2- and EXECUTER-dependent pathway operates in wild-type Arabidopsis leaves but, depending on the severity of light stress, it can be superimposed by 1O2-mediated signaling that does not depend on EXECUTER and is associated with photooxidative damage (Kim and Apel, 2013). Nevertheless, in cultured Arabidopsis cells, 1O2 was reported to be the main ROS produced in high light (González-Pérez et al., 2011). Using 1O2-specific lipid oxidation markers, Triantaphylidès et al. (2008) found that photooxidative damage to Arabidopsis leaves is always associated with 1O2-induced lipid peroxidation, indicating a central role played by this ROS in the execution of high light-induced cell death.

Mor et al. (2014) have recently shown that transcriptomes of multiple stresses, whether from light or dark treatments, are correlated with the transcriptome of the flu mutant. They also detected 1O2 production in roots in the dark, suggesting that the role of 1O2 in plant stress regulation and response is more ubiquitous than previously thought and is not restricted to high light. Lipid peroxidation and reactions between superoxide and hydrogen peroxide have been suggested as possible sources of 1O2 in the dark (Khan and Kasha, 1994; Miyamoto et al., 2007). 1O2 production can also occur under biotic stress conditions, as indicated by the accumulation of 1O2-specific lipid oxidation products in leaves during pathogen attacks (Vellosillo et al., 2010; Zoeller et al., 2012). Chlorophyll catabolites have been involved in the photosensitization of the hypersensitive response elicited by Pseudomonas syringae in Arabidopsis (Mur et al., 2010). Actually, any stress conditions that perturb the assembly of the chlorophyll binding proteins can release uncoupled chlorophyll molecules that can act as 1O2-producing photosensitizers (Santabarbara and Jennings, 2005). It is then clear that 1O2 signaling can operate under a variety of environmental conditions and can lead, likely through interactions with other signaling pathways, to physiological responses associated with cell death or acclimation.

Adaptative responses to 1O2 have also been reported in photosynthetic microorganisms. In the facultative photosynthetic α-proteobacteria Rhodobacter sphaeroides, bacteriochlorophylls can act as cellular photosensitizers. A 1O2 response mechanism was shown to occur in this organism, which involves the alternative sigma factor RpoE (Anthony et al., 2005): when cells are exposed to 1O2, the complex that RpoE forms with its anti-sigma factor ChrR is disrupted, allowing the binding of RpoE to RNA polymerase and resulting in the activation of target gene expression (Nuss et al., 2013). This transcriptional response was associated with an increased tolerance of Rhodobacter cells to 1O2. Acclimation to 1O2 was also reported in the microalga C. reinhardtii, with low sublethal concentrations of 1O2 inducing an increased resistance to higher 1O2 concentrations (Ledford et al., 2007). Recently, two mediators of 1O2-dependent gene expression have been identified in this organism: a small zinc finger protein named MBS (Shao et al., 2013) and a cytosolic phosphoprotein, SAK1 (Wakao et al., 2014). SAK1 has been proposed to be a key regulator of acclimation to 1O2 in C. reinhardtii because the SAK1 protein is phosphorylated upon exposure to 1O2 and the sak1 knock-out lacks a 1O2 acclimation response. However, SAK1 homologs have been identified only in chlorophytes. In contrast, the identification of a homologous MBS gene in Arabidopsis, and the characterization of mutant and overexpressing lines, revealed a critical and evolutionarily conserved role for the MBS protein in 1O2 signaling and photooxidative stress tolerance.

CONCLUDING REMARKS AND OUTLOOK

The study of the two 1O2-overproducing mutants, flu and ch1, has greatly improved our understanding of the cellular function of 1O2 in the model plant A. thaliana. Besides its cytotoxicity at high concentrations, 1O2 may trigger signaling pathways that lead either to acclimation or regulated cell death. Key cell death-promoting and -inhibitory signals have been identified that coexist and counteract one another and which may explain, in agreement with the competition model of cell death initiation (Galluzzi et al., 2015), how an adaptive stress response can promote cell death when unsuccessful (Figure 2). Specifically, jasmonate, and possibly other oxylipins, seem to play a central role in the decision between acclimation and cell death in the response to 1O2 (Danon et al., 2005; Ramel et al., 2013b).

The gene expression responses to 1O2 in the flu and ch1 mutants show many similarities, as expected for two 1O2 producers. Nevertheless, important differences were also observed. In particular, the dependence of the response to 1O2 on the EXECUTER proteins, which was revealed in the flu mutant, was not observed in the ch1 mutant. Furthermore, the ch1 mutant exposed to high light stress did not exhibit increased expression of EDS1 encoding the ENHANCED DISEASE SUSCEPTIBILITY1 protein that is required for the modulation of the 1O2-mediated cell death response in flu (Ochsenbein et al., 2006). Similarly, in Arabidopsis cell suspensions, EDS1 was not up-regulated during 1O2-induced cell death (Gutiérrez et al., 2014). These differences suggest that the site of 1O2 production (thylakoid membranes vs. PSII reaction centers) can modulate the gene expression response. Alternatively, or additionally, the 1O2-production rate and time might contribute to the differences observed between flu and ch1. In the flu mutant, 1O2 concentration rises immediately after the dark-to-light shift (within minutes, most likely less) and probably quite transiently since it depends on the photosensitizer Pchlide that has accumulated during the preceding dark period. Conversely, the 1O2 concentration is likely to rise more gradually in the ch1 mutant under high light stress, but the production lasts as long as the stress is maintained and the PSII reaction centers are not severely damaged. The lack of a precise and continuous determination of 1O2 concentrations emphasizes the need for the further development of highly sensitive and quantitative 1O2 detection methods that will allow the accurate detection of 1O2 in planta, and within cellular compartments (Fischer et al., 2013).

The 1O2 signaling pathways have been shown to operate in the wild-type but the situation is probably more complex than in the flu and ch1 mutants, with the interaction and the convergence of different signaling pathways (Kim and Apel, 2013). In addition, several lines of evidence indicate that the role of 1O2 in plant stress response is probably more ubiquitous than usually thought and is not exclusive to excess light energy. Indeed, not only 1O2 appears to be involved in the response to pathogen attacks, but it can also emanate from compartments other than the chloroplasts and in a light-independent manner. Therefore, a better knowledge of the plant responses to 1O2 could have important implications not only for the understanding of how plants can adapt to changing and unfavorable climatic environments, but also for the development of plants tolerant to various types of stresses, including biotic stresses.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The research works on 1O2 performed in the authors’ laboratories are supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR-14-CE02-0010 and ANR-2010-JCJC-1205 01). We thank Dr. Ben Field for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Alboresi A., Dall’osto L., Aprile A., Carillo P., Roncaglia E., Cattivelli L., et al. (2011). Reactive oxygen species and transcript analysis upon excess light treatment in wild-type Arabidopsis thaliana vs a photosensitive mutant lacking zeaxanthin and lutein. BMC Plant Biol. 11:62 10.1186/1471-2229-11-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony J. R., Warczak K. L., Donohue T. J. (2005). A transcriptional response to singlet oxygen, a toxic byproduct of photosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 6502–6507 10.1073/pnas.0502225102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avanci N. C., Luche D. D., Goldman G. H., Goldman M. H. S. (2010). Jasmonates are phytohormones with multiple functions, including plant defense and reproduction. Genet. Mol. Res. 9 484–505 10.4238/vol9-1gmr754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbi V., Devoto A. (2008). Jasmonate signalling network in Arabidopsis thaliana: crucial regulatory nodes and new physiological scenarios. New Phytol. 177 301–318 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02292.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballaré C. L. (2011). Jasmonate-induced defenses: a tale of intelligence, collaborators and rascals. Trends Plant Sci. 16 249–257 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birtic S., Ksas B., Genty B., Mueller M. J., Triantaphylidès C., Havaux M. (2011). Using spontaneous photon emission to image lipid oxidation patterns in plant tissues. Plant J. 67 1103–1115 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04646.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisby R. H., Morgan C. G., Hamblett I., Gorman A. A. (1999). Quenching of singlet oxygen by Trolox C, ascorbate, and amino acids: effects of pH and temperature. J. Phys. Chem. A 103 7454–7459 10.1021/jp990838c [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H. L., Kang C. Y., Lee T. M. (2013). Hydrogen peroxide production protects Chlamydomonas reinhardtii against light-induced cell death by preventing singlet oxygen accumulation through enhanced carotenoid synthesis. J. Plant Physiol. 170 976–986 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dall’Osto L., Cazzaniga S., Havaux M., Bassi R. (2010). Enhanced photoprotection by protein-bound vs free xanthophyll pools: a comparative analysis of chlorophyll b and xanthophyll biosynthesis mutants. Mol. Plant 3 576–593 10.1093/mp/ssp117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danon A., Coll N. S., Apel K. (2006). Cryptochrome-1-dependent execution of programmed cell death induced by singlet oxygen in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 17036–17041 10.1073/pnas.0608139103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danon A., Miersch O., Felix G., Op Den Camp R. G. L., Apel K. (2005). Concurrent activation of cell death-regulating signaling pathways by singlet oxygen in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 41 68–80 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02276.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espineda C. E., Linford A. S., Devine D., Brusslan J. A. (1999). The AtCAO gene, encoding chlorophyll a oxygenase, is required for chlorophyll b synthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 10507–10511 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estavillo G. M., Chan K. X., Phua S. Y., Pogson B. J. (2012). Reconsidering the nature and mode of action of metabolite retrograde signals from the chloroplast. Front. Plant Sci. 3:300 10.3389/fpls.2012.00300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer B. B., Hideg É., Krieger-Liszkay A. (2013). Production, detection, and signaling of singlet oxygen in photosynthetic organisms. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18 2145–2162 10.1089/ars.2012.5124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer B. B., Ledford H. K., Wakao S., Huang S. G., Casero D., Pellegrini M., et al. (2012). SINGLET OXYGEN RESISTANT 1 links reactive electrophile signaling to singlet oxygen acclimation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 E1302–E1311 10.1073/pnas.1116843109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fufezan C., Rutherford A. W., Krieger-Liszkay A. (2002). Singlet oxygen production in herbicide-treated photosystem II. FEBS Lett. 532 407–410 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03724-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadjev I., Vanderauwera S., Gechev T. S., Laloi C., Minkov I. N., Shulaev V., et al. (2006). Transcriptomic footprints disclose specificity of reactive oxygen species signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 141 436–445 10.1104/pp.106.078717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi L., Bravo-San Pedro J. M., Vitale I., Aaronson S. A., Abrams J. M., Adam D., et al. (2015). Essential versus accessory aspects of cell death: recommendations of the NCCD 2015. Cell Death Differ. 22 58–73 10.1038/cdd.2014.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Pérez S., Gutiérrez J., García-García F., Osuna D., Dopazo J., Lorenzo Ó., et al. (2011). Early transcriptional defense responses in Arabidopsis cell suspension culture under high-light conditions. Plant Physiol. 156 1439–1456 10.1104/pp.111.177766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez J., González-Pérez S., García-García F., Daly C. T., Lorenzo O., Revuelta J. L., et al. (2014). Programmed cell death activated by Rose Bengal in Arabidopsis thaliana cell suspension cultures requires functional chloroplasts. J. Exp. Bot. 65 3081–3095 10.1093/jxb/eru151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havaux M. (2014). Carotenoid oxidation products as stress signals in plants. Plant J. 79 597–606 10.1111/tpj.12386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havaux M., Dall’osto L., Bassi R. (2007). Zeaxanthin has enhanced antioxidant capacity with respect to all other xanthophylls in Arabidopsis leaves and functions independent of binding to PSII antennae. Plant Physiol. 145 1506–1520 10.1104/pp.107.108480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havaux M., Ksas B., Szewczyk A., Rumeau D., Franck F., Caffarri S., et al. (2009). Vitamin B6 deficient plants display increased sensitivity to high light and photo-oxidative stress. BMC Plant Biol. 9:130 10.1186/1471-2229-9-130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havaux M., Tardy F. (1997). Thermostability and photostability of photosystem II in leaves of the chlorina-f2 barley mutant deficient in light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b protein complexes. Plant Physiol. 113 913–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A. U., Kasha M. (1994). Singlet molecular oxygen in the Haber-Weiss reaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91 12365–12367 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C., Apel K. (2013). Singlet oxygen-mediated signaling in plants: moving from flu to wild type reveals an increasing complexity. Photosynth. Res. 116 455–464 10.1007/s11120-013-9876-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C., Meskauskiene R., Apel K., Laloi C. (2008). No single way to understand singlet oxygen signalling in plants. EMBO Rep. 9 435–439 10.1038/embor.2008.57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C., Meskauskiene R., Zhang S., Lee K. P., Lakshmanan Ashok M., Blajecka K., et al. (2012). Chloroplasts of Arabidopsis are the source and a primary target of a plant-specific programmed cell death signaling pathway. Plant Cell 24 3026–3039 10.1105/tpc.112.100479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E.-H., Li X.-P., Razeghifard R., Anderson J. M., Niyogi K. K., Pogson B. J., et al. (2009). The multiple roles of light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b-protein complexes define structure and optimize function of Arabidopsis chloroplasts: a study using two chlorophyll b-less mutants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787 973–984 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger-Liszkay A., Fufezan C., Trebst A. (2008). Singlet oxygen production in photosystem II and related protection mechanism. Photosynth. Res. 98 551–564 10.1007/s11120-008-9349-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laloi C., Przybyla D., Apel K. (2006). A genetic approach towards elucidating the biological activity of different reactive oxygen species in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 57 1719–1724 10.1093/jxb/erj183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laloi C., Stachowiak M., Pers-Kamczyc E., Warzych E., Murgia I., Apel K. (2007). Cross-talk between singlet oxygen- and hydrogen peroxide-dependent signaling of stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 672–677 10.1073/pnas.0609063103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledford H. K., Chin B. L., Niyogi K. K. (2007). Acclimation to singlet oxygen stress in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Eukaryot. Cell 6 919–930 10.1128/EC.00207-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. P., Kim C., Landgraf F., Apel K. (2007). EXECUTER1- and EXECUTER2-dependent transfer of stress-related signals from the plastid to the nucleus of Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 10270–10275 10.1073/pnas.0702061104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A., Tenhaken R., Dixon R., Lamb C. (1994). H2O2 from the oxidative burst orchestrates the plant hypersensitive disease resistance response. Cell 79 583–593 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90544-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Melø T. B., Arellano J. B., Razi Naqvi K. (2012). Temporal profile of the singlet oxygen emission endogenously produced by photosystem II reaction centre in an aqueous buffer. Photosynth. Res. 112 75–79 10.1007/s11120-012-9739-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meskauskiene R., Apel K. (2002). Interaction of FLU, a negative regulator of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis, with the glutamyl-tRNA reductase requires the tetratricopeptide repeat domain of FLU. FEBS Lett. 532 27–30 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03617-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meskauskiene R., Nater M., Goslings D., Kessler F., op den Camp R., Apel K. (2001). FLU: a negative regulator of chlorophyll biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 12826–12831 10.1073/pnas.221252798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S., Ronsein G. E., Prado F. M., Uemi M., Corrêa T. C., Toma I. N., et al. (2007). Biological hydroperoxides and singlet molecular oxygen generation. IUBMB Life 59 322–331 10.1080/15216540701242508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor A., Koh E., Weiner L., Rosenwasser S., Sibony-Benyamini H., Fluhr R. (2014). Singlet oxygen signatures are detected independent of light or chloroplasts in response to multiple stresses. Plant Physiol. 165 249–261 10.1104/pp.114.236380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mur L. A. J., Aubry S., Mondhe M., Kingston-Smith A., Gallagher J., Timms-Taravella E., et al. (2010). Accumulation of chlorophyll catabolites photosensitizes the hypersensitive response elicited by Pseudomonas syringae in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 188 161–174 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03377.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgia I., Tarantino D., Vannini C., Bracale M., Carravieri S., Soave C. (2004). Arabidopsis thaliana plants overexpressing thylakoidal ascorbate peroxidase show increased resistance to Paraquat-induced photooxidative stress and to nitric oxide-induced cell death. Plant J. 38 940–953 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02092.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuss A. M., Adnan F., Weber L., Berghoff B. A., Glaeser J., Klug G. (2013). DegS and RseP homologous proteases are involved in singlet oxygen dependent activation of RpoE in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. PLoS ONE 8:e79520 10.1371/journal.pone.0079520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsenbein C., Przybyla D., Danon A., Landgraf F., Göbel C., Imboden A., et al. (2006). The role of EDS1 (enhanced disease susceptibility) during singlet oxygen-mediated stress responses of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 47 445–456 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02793.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T., Uchimiya H., Kawai-Yamada M. (2007). Mutual regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana ethylene-responsive element binding protein and a plant floral homeotic gene, APETALA2. Ann. Bot. 99 239–244 10.1093/aob/mcl265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- op den Camp R. G. L., Przybyla D., Ochsenbein C., Laloi C., Kim C., Danon A., et al. (2003). Rapid induction of distinct stress responses after the release of singlet oxygen in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 15 2320–2332 10.1105/tpc.014662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plumley F. G., Schmidt G. W. (1987). Reconstitution of chlorophyll a/b light-harvesting complexes: Xanthophyll-dependent assembly and energy transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84 146–150 10.1073/pnas.84.1.146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przybyla D., Göbel C., Imboden A., Hamberg M., Feussner I., Apel K. (2008). Enzymatic, but not non-enzymatic, 1O2-mediated peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids forms part of the EXECUTER1-dependent stress response program in the flu mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 54 236–248 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03409.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramel F., Birtic S., Cuiné S., Triantaphylidès C., Ravanat J.-L., Havaux M. (2012a). Chemical quenching of singlet oxygen by carotenoids in plants. Plant Physiol. 158 1267–1278 10.1104/pp.111.182394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramel F., Birtic S., Ginies C., Soubigou-Taconnat L., Triantaphylidès C., Havaux M. (2012b). Carotenoid oxidation products are stress signals that mediate gene responses to singlet oxygen in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 5535–5540 10.1073/pnas.1115982109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramel F., Ksas B., Akkari E., Mialoundama A. S., Monnet F., Krieger-Liszkay A., et al. (2013a). Light-induced acclimation of the Arabidopsis chlorina1 mutant to singlet oxygen. Plant Cell 25 1445–1462 10.1105/tpc.113.109827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramel F., Ksas B., Havaux M. (2013b). Jasmonate: a decision maker between cell death and acclimation in the response of plants to singlet oxygen. Plant Signal. Behav. 8 e26655. 10.4161/psb.26655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond R. W., Kochevar I. E. (2006). Spatially resolved cellular responses to singlet oxygen. Photochem. Photobiol. 82 1178–1186 10.1562/2006-04-14-IR-874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinbothe C., Springer A., Samol I., Reinbothe S. (2009). Plant oxylipins: role of jasmonic acid during programmed cell death, defence and leaf senescence. FEBS J. 276 4666–4681 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07193.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reymond P., Farmer E. E. (1998). Jasmonate and salicylate as global signals for defense gene expression. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 1 404–411 10.1016/S1369-5266(98)80264-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabater B., Martín M. (2013). Hypothesis: increase of the ratio singlet oxygen plus superoxide radical to hydrogen peroxide changes stress defense response to programmed leaf death. Front. Plant Sci. 4:479 10.3389/fpls.2013.00479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santabarbara S., Jennings R. C. (2005). The size of the population of weakly coupled chlorophyll pigments involved in thylakoid photoinhibition determined by steady-state fluorescence spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1709 138–149 10.1016/j.bbabio.2005.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao N., Duan G. Y., Bock R. (2013). A mediator of singlet oxygen responses in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Arabidopsis identified by a luciferase-based genetic screen in algal cells. Plant Cell 25 4209–4226 10.1105/tpc.113.117390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumbe L., Bott R., Havaux M. (2014). Dihydroactinidiolide, a high light-induced β-carotene derivative that can regulate gene expression and photoacclimation in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 7 1248–1251 10.1093/mp/ssu028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takabayashi A., Kurihara K., Kuwano M., Kasahara Y., Tanaka R., Tanaka A. (2011). The oligomeric states of the photosystems and the light-harvesting complexes in the Chl b-less mutant. Plant Cell Physiol. 52 2103–2114 10.1093/pcp/pcr138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telfer A. (2014). Singlet oxygen production by PSII under light stress: mechanism, detection and the protective role of β-carotene. Plant Cell Physiol. 55 1216–1223 10.1093/pcp/pcu040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thordal-Christensen H., Zhang Z., Wei Y., Collinge D. B. (1997). Subcellular localization of H2O2 in plants. H2O2 accumulation in papillae and hypersensitive response during the barley-powdery mildew interaction. Plant J. 11 1187–1194 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.11061187.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Triantaphylidès C., Havaux M. (2009). Singlet oxygen in plants: production, detoxification and signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 14 219–228 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triantaphylidès C., Krischke M., Hoeberichts F. A., Ksas B., Gresser G., Havaux M., et al. (2008). Singlet oxygen is the major reactive oxygen species involved in photooxidative damage to plants. Plant Physiol. 148 960–968 10.1104/pp.108.125690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Doorn W. G., Beers E. P., Dangl J. L., Franklin-Tong V. E., Gallois P., Hara-Nishimura I., et al. (2011). Morphological classification of plant cell deaths. Cell Death Differ. 18 1241–1246 10.1038/cdd.2011.36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wees S. C. M., Glazebrook J. (2003). Loss of non-host resistance of Arabidopsis NahG to Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola is due to degradation products of salicylic acid. Plant J. 33 733–742 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01665.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellosillo T., Vicente J., Kulasekaran S., Hamberg M., Castresana C. (2010). Emerging complexity in reactive oxygen species production and signaling during the response of plants to pathogens. Plant Physiol. 154 444–448 10.1104/pp.110.161273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner D., Przybyla D., Op den Camp R., Kim C., Landgraf F., Lee K. P., et al. (2004). The genetic basis of singlet oxygen-induced stress responses of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 306 1183–1185 10.1126/science.1103178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakao S., Chin B. L., Ledford H. K., Dent R. M., Casero D., Pellegrini M., et al. (2014). Phosphoprotein SAK1 is a regulator of acclimation to singlet oxygen in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Elife 3:e02286 10.7554/eLife.02286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson F., Helman W. P., Ross A. B. (1995). Rate constants for the decay and reactions of the lowest electronically excited singlet state of molecular oxygen in solution. An expanded and revised compilation. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 24 663 10.1063/1.555965 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Apel K., Kim C. (2014). Singlet oxygen-mediated and EXECUTER-dependent signalling and acclimation of Arabidopsis thaliana exposed to light stress. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 369:20130227 10.1098/rstb.2013.0227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoeller M., Stingl N., Krischke M., Fekete A., Waller F., Berger S., et al. (2012). Lipid profiling of the Arabidopsis hypersensitive response reveals specific lipid peroxidation and fragmentation processes: biogenesis of pimelic and azelaic acid. Plant Physiol. 160 365–378 10.1104/pp.112.202846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]