Abstract

Bipolar spectrum disorders (BSDs) are often characterized by cognitive inflexibility and affective extremities, including “extreme” or polarized thoughts and beliefs, which have been shown to predict a more severe course of illness. However, little research has evaluated factors that may be associated with extreme cognitions, such as personality disorders, which are often characterized by extreme, inflexible beliefs and also are associated with poor illness course in BSDs. The present study evaluated associations between BSDs, personality disorder characteristics, and extreme cognitions (polarized responses made on measures of attributional style and dysfunctional attitudes), as well as links between extreme cognitions and the occurrence of mood episodes, among euthymic young adults with BSDs (n = 83) and demographically-matched healthy controls (n = 89) followed prospectively for three years. The relationship between personality disorder characteristics and negative and positive extreme cognitions was stronger among BSD participants than among healthy controls, even after statistically accounting for general cognitive styles. Furthermore, extreme negative cognitions predicted the prospective onset of major depressive and hypomanic episodes. These results suggest that extreme cognitive styles are most common in individuals with BSDs and personality disorder characteristics, and they provide further evidence that extreme negative cognitions may confer risk for mood dysregulation.

Keywords: Extreme attributions, attributional style, dysfunctional attitudes, cognitive style, personality disorders, bipolar disorder, extreme response style

“...Two extremes ought not to be practiced... there is addiction to indulgence of sense-pleasures... and there is addiction to self-mortification, which is painful, unworthy, and unprofitable... avoiding both these extremes [is] the middle path... [which] gives knowledge and lends to calm, to insight, to enlightenment.”

--Buddha (Buddhist Publication Society, 1999)

Bipolar disorder (BD) can be a severe mood disorder with a chronic course that is characterized by periods of mood elevation or irritability and depression (APA, 2013), as well as impairment in many areas of functioning (Angst et al., 2002; Goodwin & Jamison, 2007; Grant et al., 2004; Judd & Akiskal, 2003; Judd et al., 2008). BDs form a spectrum of severity from the milder cyclothymic disorder to full-blown bipolar I disorder, and milder forms of bipolar spectrum disorders (BSDs) sometimes progress to more severe BSDs (e.g., Akiskal et al., 1977; Alloy et al., 2012; Birmaher et al., 2009). Many individuals with BSDs experience a course of illness that is highly recurrent with frequent mood episodes (Nierenberg et al., 2010; Perlis et al., 2006). Thus, identifying which individuals may experience a more severe course of illness potentially has major implications for improving interventions and public health care (Johnson & Meyer, 2005).

One characteristic that has been useful in identifying risk for poor illness course in BSDs is negative cognitive style (the tendency to attribute negative events to causes that are stable and global with negative consequences and self-implications) (for a review, see Alloy et al., 2005). Existing prospective studies have demonstrated that in interaction with life events, both pessimistic and optimistic attributional styles predicted increases in hypomanic symptoms in individuals with BSDs, whereas only pessimistic attributional styles predicted increases in symptoms of depression (Alloy et al., 1999; Reilly-Harrington et al., 1999) and longer duration of depressive episodes in interaction with initial depression severity (Stange et al., 2013a).

Individuals with BSDs also have elevated levels of dysfunctional attitudes, or maladaptive beliefs about the self and the world (Alloy et al., 2005). In BSDs, dysfunctional attitudes also have predicted increases in symptoms of depression (Johnson & Fingerhut, 2004), and in interaction with life events they have predicted increases in manic symptoms (Reilly-Harrington et al., 1999). Similarly, Francis-Raniere et al. (2006) found that in individuals with BSDs, dysfunctional attitudes about performance evaluation predicted increases in hypomanic and depressive symptoms following congruent stressors. However, not all studies of BSDs have found a prospective association between dysfunctional attitudes and illness course; for example, in one study, dysfunctional attitudes did not predict the prospective onset of episodes of depression or hypomania (Alloy et al., 2009).

Corroborating similar findings in individuals with major depressive disorder (Petersen et al., 2007; Teasdale et al., 2001), recent work also has demonstrated that extreme attributions (extreme negative cognitive styles) about the causes of life events (e.g., “I lost my job because I am a complete failure as a person”) are associated with a more severe course of bipolar illness. Among depressed adults with bipolar I or II disorders, the tendency to make extreme attributions predicted a longer duration of episodes of depression, greater likelihood of a history of suicide attempts and of suicidal ideation among previous attempters, and a shorter time until the onset of episodes of mania, hypomania, or mixed episodes (Stange et al., 2013a,b, 2014). These results were consistent across extreme pessimistic and extreme optimistic attributions, suggesting that the tendency to make extreme attributions in general might be more important in understanding course of illness than the valence of the attributions themselves. These studies have been broadly consistent with theoretical work and empirical studies of BSDs that suggest that individuals with BSDs make extreme appraisals about the meaning of internal mood states (Jones et al., 2006; Kelly et al., 2011; Mansell et al., 2007, 2011), and that these appraisals are associated with increases in symptoms of mood elevation and depression (Dodd et al., 2011). Notably, although studies among samples with unipolar depression also have found that extreme dysfunctional attitudes predict a poorer course of depression (Beevers et al., 2003; Forand & DeRubeis, 2014; Petersen et al., 2007; Teasdale et al., 2001), no study to date has evaluated this question in BSDs.

Given that extreme cognitions may be predictive of a worse course of illness in mood disorders, it is important to identify clinical characteristics associated with these cognitive tendencies in BSDs. One such set of characteristics that may be promising is personality disorders, which are frequently comorbid with BSDs (Fan & Hassell, 2008), and, like extreme cognitions, are also linked to a more severe course of BSDs (Bieling et al., 2003; Dunayevich et al., 2000; George et al., 2003). Personality disorders are characterized by extreme, inflexible behaviors and beliefs that are maintained across different contexts in which they may be maladaptive (APA, 2013; Beck et al., 2006). For example, individuals with borderline personality disorder engage in extreme dichotomous thinking styles when presented with emotionally-relevant stimuli (Arntz et al., 2011). However, although extreme cognitions are likely to be elevated in BSDs, it is unclear whether personality disorders contribute additional risk for having extreme cognitions; for example, it is unclear whether individuals with BSDs in conjunction with personality disorders are more likely to exhibit extreme cognitions relative to healthy controls. These questions are important given that extreme cognitions may be associated with a poorer course of illness in mood disorders.

In the present study, we sought to elucidate these questions by evaluating extreme cognitions, personality disorder characteristics, and course of illness in a prospective study of young adults with bipolar spectrum disorders (bipolar II, bipolar NOS, and cyclothymia) and matched controls. We hypothesized (1) that personality disorder characteristics would be associated with extreme cognitions more strongly among individuals with BSDs relative to healthy controls; and (2) that relative to individuals with less extreme cognitions, individuals with more extreme cognitions would be more likely to experience the prospective onset of episodes of major depression and hypomania.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants in this study were drawn from the Temple University site of the Longitudinal Investigation of Bipolar Spectrum Disorders (LIBS) Project, which examined various factors that may influence the course of bipolar spectrum disorders. A two-phase screening process was used to select participants. In Phase I, approximately 7,500 university students completed the General Behavior Inventory (GBI; Depue et al., 1989). Based on the GBI cutoff criteria (see measures), 12.3% of the sample was eligible for the bipolar spectrum disorder (BSD) group, and 65% was potentially eligible for the control group. Up to four months after Phase I, 684 potentially eligible individuals completed a diagnostic interview for Phase II screening.

In Phase II, inclusion criteria for the BSD group were a lifetime diagnosis of bipolar II disorder, cyclothymia, or bipolar not otherwise specified (NOS), as determined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV; APA, 1994) or Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC; Spitzer et al., 1978). The bipolar NOS group was comprised of individuals who had experienced three types of symptoms: (a) hypomanic episode(s) but no diagnosable depressive episodes, (b) a cyclothymic mood pattern with periods of affective disturbance that did not meet frequency/duration criteria for hypomanic and depressive episodes, or (c) hypomanic and depressive episodes not meeting frequency criteria for a diagnosis of cyclothymia.1 Participants were excluded from the BSD group if they experienced a manic episode as defined by the DSM-IV or RDC criteria, as this would indicate a bipolar I diagnosis (and an aim of the overall LIBS Project was to predict conversion to bipolar I). The control group had two exclusion criteria: (a) current or past diagnosis of any Axis I disorder, and (b) family history of a mood disorder.

The final sample consisted of a total of 172 participants (n = 83 BSD, n = 89 healthy; mean age = 19.79), with BSD participants matched with respect to gender, age, and ethnicity by the control group (see Table 1 for group comparisons). Of the BSD participants, 63% met criteria for bipolar II disorder, 25% met criteria for cyclothymia, and 12% met for bipolar NOS. Approximately 15% of the BSD sample had sought treatment (medication or psychotherapy) prior to the study, and 31% of the BSD sample sought treatment during the study (16% medication only, 13% psychotherapy only, and 3% were hospitalized) (Alloy et al., 2008).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Descriptive Statistics for the Study Sample

| BSD (n = 83) | Healthy Controls (n = 89) | Group Difference (χ2 or t) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 61.25% | 67.44% | 0.69 |

| Age | 19.56 (1.77) | 20.04 (1.98) | −1.68 |

| Race | 2.52 | ||

| Caucasian | 51.25% | 55.81% | |

| African-American | 30.00% | 22.09% | |

| Hispanic | 3.75% | 3.49% | |

| Asian | 3.75% | 8.14% | |

| Other | 11.25% | 10.47% | |

| BDI | 11.42 (10.17) | 2.71 (3.31) | 7.35*** |

| HMI | 15.03 (9.48) | 13.23 (7.43) | 1.38 |

| CSQ Extreme Pessimistic | 15.51 (12.48) | 10.90 (9.09) | 2.72** |

| CSQ Extreme Optimistic | 22.48 (16.12) | 23.51 (15.72) | −0.42 |

| CSQ Total Score | −.89 (1.43) | −1.84 (.88) | 4.84*** |

| DAS Extreme Negative | 2.75 (4.23) | 1.79 (2.39) | 1.79 |

| DAS Extreme Positive | 7.51 (7.10) | 11.18 (8.71) | −2.99** |

| DAS Total Score | 136.91 (36.01) | 110.18 (28.72) | 5.03*** |

| IPDE Sum Score | 11.98 (9.04) | 3.32 (5.12) | 7.57*** |

| Hypomanic Episode (Prospective) | 32.10% | 2.30% | 26.82*** |

| Major Depressive Episode (Prospective) | 41.98% | 3.45% | 36.26*** |

* p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Note. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; HMI = Halberstadt Mania Inventory; CSQ = Cognitive Style Questionnaire; DAS = Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale; IPDE = International Personality Disorder Examination. Values presented as mean (standard deviation) or as percentages for nominal variables.

Prior to entering the study, all participants provided written informed consent. The study was IRB approved by Temple University. At a Time 1 visit following the Phases I and II screening, participants completed self-report measures of negative cognitive style, dysfunctional attitudes, and symptoms of depression and hypomania. They also completed an interview assessing personality disorder characteristics. Participants completed diagnostic interviews assessing DSM-IV episodes of major depression and (hypo)mania every four months after the Time 1 visit for an average of three years of follow-up (M = 1067 days; SD = 472 days).

Interviews to assess diagnoses, mood episodes, and personality disorder characteristics were completed by intensively-trained doctoral students in clinical psychology and post-baccalaureate research assistants, all of whom were supervised by a clinical psychologist with extensive experience in diagnosing mood disorders, as well as by a masters level director of diagnostic training (Alloy et al., 2008). Training consisted of an extensive series of lectures, observations of trained interviewers, practice diagnostic interviews, and live-supervised interviews prior to interviewers completing interviews with participants by themselves. Diagnostic interviews were audiotaped to obtain consensus diagnoses and to assess inter-rater reliability. Two independent assessors computed inter-rater reliability by re-rating interviews for diagnoses and personality disorder characteristics. An expert M.D. psychiatric diagnostic consultant served as the third diagnostic tier, reviewing all diagnostic interviews with the clinical psychologist and coming to a consensus diagnosis in cases of initial disagreement.

Measures

General Behavior Inventory

The GBI (Depue et al., 1989) is a self-report questionnaire used during the Phase I screening process to identify and distinguish between potential bipolar spectrum participants and healthy controls. The GBI has been shown to be valid among a wide range of populations, including undergraduates, psychiatric outpatients, and relatives of bipolar I probands (Depue et al, 1989; Klein et al., 1985). Psychometric properties of the instrument are strong, with a reported internal consistency of αs= 0.90-0.96, retest reliability of rs= 0.71-0.74, good sensitivity (0.78), and excellent specificity (0.99) for bipolar spectrum disorders (Depue et al., 1981, 1989). Each item is designed to assess various experiences related to depressive, (hypo)manic, or biphasic symptoms, and how said experiences range on the dimensions of intensity, duration, and frequency. The respondent provides a rating on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very often or almost constantly). Consistent with scoring by Depue and colleagues (1989), an item received one point when rated as 3 (often) or 4 (very often or almost constantly) on the scale. Points were then summed to obtain two subscores: depression (GBI-D score) and (hypo)mania and biphasic (GBI-HB score). Based on Depue et al.'s (1989) findings, the following cutoff scores were used to identify potential bipolar spectrum and control participants: GBI-D scores ≥ 11 and GBI-HB scores ≥ 13 for potential bipolar spectrum participants, and GBI-D scores < 11 and GBI-HB scores < 13 for normal controls. A pilot study for the LIBS project validated this high-GBI and low-GBI group assignment procedure against diagnoses obtained via Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia interviews (see Alloy et al., 2008).

Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia – Lifetime version

(SADS-L; Endicott & Spitzer, 1978). During Phase II of the screening process, semistructured diagnostic interviews were conducted using an expanded version of the SADS-L (exp-SADS-L; Alloy et al., 2008, 2012), which assesses symptoms related to mood, anxiety, eating, psychotic, and substance use disorders over the lifetime. The exp-SADS-L was expanded from the original SADS-L by our group to include additional probes to allow for DSM-IV and RDC to be assessed (Alloy et al., 2008, 2012), including increasing the number of items in the depression, mania/hypomania, and cyclothymia sections, and expansion of information obtained in terms of the timing of symptoms and episodes. Inter-rater reliability was high: kappas for major depressive disorder diagnoses based on 80 jointly rated interviews were κ = .95, and bipolar spectrum diagnoses based on 105 jointly rated interviews yielded κ = .96 (Alloy et al., 2008).

International Personality Disorder Examination for DSM-IV

(IPDE; Loranger, 1996). The IPDE is a semistructured interview that assesses dimensions of DSM-IV personality pathology. Trained interviewers were required to rate items based on participants’ verbal responses and observable behaviors during the interview's administration. Each DSM-IV personality disorder diagnosis is represented by a multitude of items. Dimensional scores for each disorder, and characteristics across all personality disorders (IPDE sum score), are computed by adding the individual items for that domain to calculate severity (Loranger, 1996; Pilkonis et al., 1991). The IPDE yields continuous scores of severity for each of the 10 DSM-IV personality disorder diagnoses, as well as a total score representing total personality disorder pathology. In the current study, our primary measure was the IPDE total score, with post-hoc analyses conducted using individual personality disorder dimension scores. The IPDE has demonstrated excellent inter-rater reliability, with κs = .79- .84 (Pilkonis et al., 1991), and good dimensional score consistency with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (Spitzer et al., 1987). In the present sample, with the exception of schizotypal personality (κ = .46), the IPDE had acceptable inter-rater reliability based on 40 interview re-ratings (23% of interviews), with κs = .69 - .88 (Cogswell & Alloy, 2006).

Cognitive Style Questionnaire

The Cognitive Style Questionnaire (CSQ; Alloy et al., 2000; Haeffel et al., 2008) was used to assess participants' attributional styles for positive and negative events. The CSQ is a well-established instrument with good reliability and validity (Haeffel et al., 2008) that assesses attributions about the causes, consequences, and self-implications for hypothetical positive and negative events on four dimensions relevant to the hopelessness theory of depression: stability (“will never again cause [the event]” to “will also cause [the event] in the future”), globality (“will only cause problems with [the event]” to “will cause problems in all areas of my life”), consequences (“nothing bad will happen” to “very bad things will happen”), and self-implications (“doesn't mean anything is wrong with me” to “definitely means something is wrong with me”). The CSQ contains 12 positive and 12 negative events and requires participants to rate each event on each of the four dimensions on 7-point Likert scales. The CSQ yields a total score, with higher scores indicating more negative cognitive style; possible range is −6 to +6 (observed range: −4.46-3.00). Consistent with previous studies (Petersen et al., 2007; Stange et al., 2013a,b, 2014; Teasdale et al., 2001), we also computed the number of “extreme” attributions (rating of a 1 or 7) made on each attributional domain for each event, resulting in variables for extreme pessimistic attributions (number of ratings of “7” for negative events and ratings of “1” for positive events; possible range is 0-96, observed range was 0-62), and extreme optimistic attributions (number of ratings of “1” for negative events and ratings of “7” for positive events; possible range is 0-96, observed range was 0-78). Internal consistency of the CSQ was excellent (α = .94). Although retest reliability of extreme responses on the CSQ has not been established, predictive validity on similar measures of attributional style has been established; extreme attributions predicted poorer course of illness in depression (Petersen et al., 2007; Teasdale et al., 2001) and bipolar disorder (Stange et al., 2013a,b).

Dysfunctional Attitude Scale.

The Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS; Weissman & Beck, 1978) is a 40-item self-report questionnaire that assesses dysfunctional, maladaptive beliefs about one's self-worth and the future. Using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Totally agree’ to ‘Totally disagree’, participants are asked to respond to descriptions of their attitudes most of the time (e.g., “If I do not do as well as other people, it means I am an inferior human being”). The DAS yields a total score representing total dysfunctional attitudes (possible range is 40-280; observed range was 55-232). We also computed the number of “extreme” dysfunctional attitudes (number of items coded “1” or “7”) yielding variables for extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes (“1” on negatively valenced items; “7” on positively valenced items; possible range is 0-40, observed range was 0-26) and extreme positive dysfunctional attitudes (“7” on negatively valenced items; “1” on positively valenced items; possible range is 0-40, observed range was 0-32), consistent with previous studies of unipolar depression (Beevers et al., 2003; Petersen et al., 2007; Teasdale et al., 2001). The DAS has demonstrated good construct validity (Alloy et al., 2000; Francis-Raniere et al., 2006) and in the present study had an internal consistency of α = .80. Although retest reliability of extreme responses on the DAS has not been established, predictive validity has been established; extreme responses predicted depressive relapse in several studies of unipolar depression (Beevers et al., 2003; Forand & DeRubeis, 2014; Petersen et al., 2007; Teasdale et al., 2001).

Schedule for Affective Disorders – Change version

(SADS-C; Endicott & Spitzer, 1978). The expanded SADS-C (exp-SADS-C) is a semistructured interview that inquires about the occurrence, duration, and symptom severity of mood, anxiety, psychotic, and substance use disorders. It was expanded by our group (Alloy et al., 2008, 2012) in the same ways as the exp-SADS-L (described above). The exp-SADS-C was conducted at follow-up assessments to diagnose DSM-IV episodes of major depression and (hypo)mania (see also Alloy et al., 2008; 2012; Francis-Raniere et al., 2006). Exp-SADS-C interviewers were blind to participants’ Phase I GBI scores as well as their SADS-L diagnoses. Based on 60 jointly rated LIBS Project interviews, inter-rater reliability for the exp-SADS-C was strong (κ = .80; Francis-Raniere et al., 2006). In a validity study, participants identified the dates of their symptoms on the exp-SADS-C compared to daily symptom ratings made over a four-month interval with greater than 70% accuracy (Alloy et al., 2008).

Beck Depression Inventory

(BDI; Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979). The BDI is a 21-item self-report inventory that assesses the presence and severity of cognitive, motivational, affective, and somatic symptoms of depression over the past month. The BDI has been shown to be valid among student samples (Bumberry et al., 1978; Hammen, 1980). The BDI was administered at the Time 1 visit to assess current symptoms of depression. Internal consistency of the BDI was excellent (α = .94). Scores can range from 0-63 (observed range was 0-50).

The Halberstadt Mania Inventory

(HMI; Alloy et al., 1999; Halberstadt & Abramson, 2007) is a 28-item self-report measure that assesses current cognitive, motivational, affective and somatic symptoms associated with mania/hypomania over the past month. The HMI was modeled after the BDI format and is thus administered and scored in a similar manner. In a sample of approximately 1,282 undergraduates, the HMI had high internal consistency (α = .82), adequate convergent validity with mania symptoms on the exp-SADS-C (r = .46; Alloy et al., 2008) and on the mania scale of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (Hathaway & McKinley, 1951; r = .32, p < .001), and discriminant validity (r = –.26, p < .001 with the depression scale of the MMPI and r = −.12, p < .001 with the BDI; Halberstadt & Abramson, 2007). Evidence of the construct validity of the HMI has been provided by Alloy et al. (1999). The HMI was administered at the Time 1 visit to assess current symptoms of hypomania. Internal consistency of the HMI was good (α = .83). Scores can range from 0-84 (observed range was 3-50).

Statistical Analyses

To evaluate Hypothesis 1, that personality disorder characteristics would be associated with extreme cognitions more strongly among individuals with BSDs relative to healthy controls, we conducted hierarchical linear regressions. In Step 1, we entered Time 1 symptoms of depression and hypomania, and either negative cognitive style total score (when predicting extreme attributions) or dysfunctional attitudes total score (when predicting extreme dysfunctional attitudes), thus providing conservative tests by predicting extreme cognitions beyond general cognitive styles. The main effects of BSD status and IPDE were entered in Step 2, followed by the interaction term between BSD and IPDE in Step 3. Each extreme cognitive measure (extreme pessimistic attributions, extreme optimistic attributions, extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes, and extreme positive dysfunctional attitudes) served as an outcome variable. Simple slopes tests were conducted for significant interactions by evaluating the association between personality disorder characteristics and extreme cognitions among individuals with BSDs and among healthy controls (Aiken & West, 1991). As recommended by Aiken and West, BSD status was dichotomized and coded as 0 (healthy control) or 1 (BSD). All analyses with the IPDE were conducted first using the total score, with post-hoc analyses investigating IPDE subscales for any relationships that were significant using the total score. IPDE scores were mean-centered (Aiken & West, 1991). Anticipating a small-to-medium effect size with 80% power and six predictors, power analyses indicated that a sample of 142 individuals would be needed; thus, our sample size was appropriate.

To evaluate Hypothesis 2, that relative to individuals with less extreme cognitions, individuals with more extreme cognitions would be more likely to experience the prospective onset of episodes of major depression and hypomania, we conducted logistic regression analyses. Extreme cognitions were entered as predictors individually in separate analyses (after controlling for Time 1 symptoms of depression and hypomania and time in the study). Analyses were then repeated controlling for either negative cognitive style total score (in analyses containing extreme attributions) or dysfunctional attitudes total score (in analyses containing extreme dysfunctional attitudes), to examine the unique ability of extreme cognitions to predict depression and hypomania beyond general cognitive styles. Anticipating a small-to-medium effect size with 80% power and five predictors, power analyses indicated that a sample of 134 individuals would be needed; thus our sample size was appropriate.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Before conducting our primary analyses, independent samples t-tests were used to evaluate differences between BSD and healthy controls on study variables (Table 1). Relative to healthy controls, BSD participants exhibited more overall negative cognitive styles (CSQ Total Score) and more extreme pessimistic attributions, but not more extreme optimistic attributions. Individuals with BSDs also had higher levels of dysfunctional attitudes overall (DAS Total Score), and had fewer extreme optimistic dysfunctional attitudes. BSD participants also had higher levels of personality disorder characteristics, more Time 1 depressive symptoms, and were more likely to experience the onset of episodes of hypomania and depression across follow-up. The groups did not differ on Time 1 hypomanic symptoms, age, gender, or race. Acrossfollow-up, 28 individuals experienced the onset of a hypomanic episode, whereas 37 individuals experienced the onset of a major depressive episode.

Additionally, extreme pessimistic attributions and extreme optimistic attributions were significantly moderately correlated (r = .46, p < .001). The correlation between extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes and extreme positive dysfunctional attitudes did not meet significance (r = .15, p = .06). Extreme pessimistic attributions and extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes were significantly moderately correlated (r = .61, p < .0001).

Hypothesis 1: Are Personality Disorder Characteristics More Strongly Associated with Extreme Cognitions Among Individuals with BSDs?

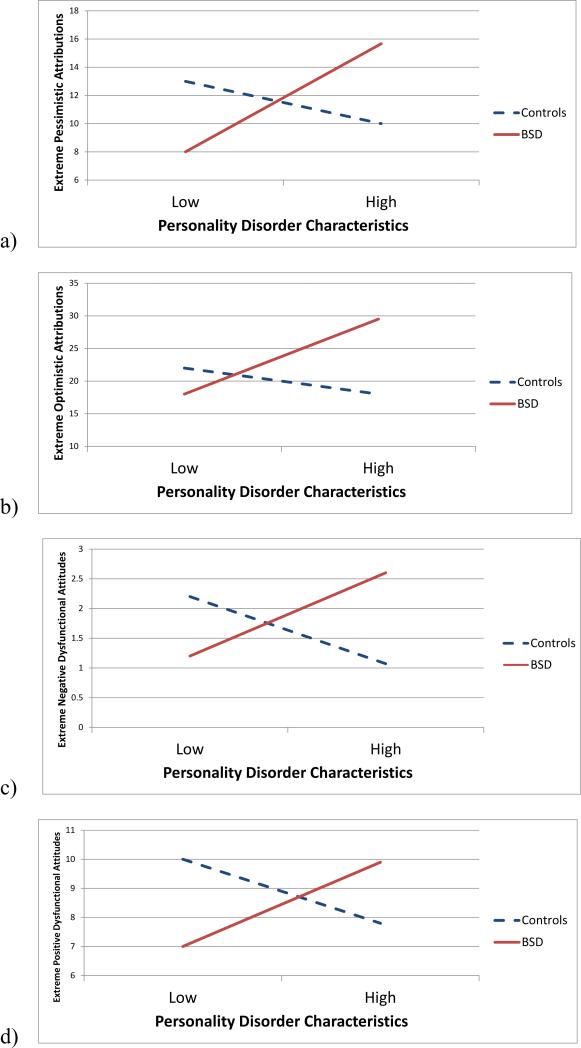

As hypothesized, BSD status interacted with the IPDE total score to predict extreme pessimistic attributions (Table 2; Figure 1a), such that there was a significant association between personality disorder characteristics and extreme pessimistic attributions among individuals with BSDs (t = 3.97, p = .0001), but not among healthy controls (t = −0.92, p = .36). Post-hoc analyses revealed that this interaction was significant in the same directions using the borderline (t = 3.09, p < .01), histrionic (t = 2.41, p = .02), and dependent (t = 2.26, p = .03) subscales of the IPDE.

Table 2.

Interactions between Bipolar Spectrum Disorder Status and Personality Disorder Characteristics Predicting Extreme Attributional Styles and Dysfunctional Attitudes.

| Extreme Pessimistic Attributions | Extreme Optimistic Attributions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step | Variable | β | t | ΔR2 | Variable | β | t | ΔR2 |

| 1 | BDI | −.01 | −0.09 | .22*** | BDI | .09 | 1.26 | .24*** |

| HMI | .05 | 0.63 | HMI | .03 | 0.47 | |||

| CSQ Total | .47 | 6.02*** | CSQ Total | −.51 | −6.58*** | |||

| 2 | BDI | −.04 | −0.49 | .04* | BDI | .01 | 0.13 | .04* |

| HMI | .04 | 0.51 | HMI | .01 | −.10 | |||

| CSQ Total | .45 | 5.66*** | CSQ Total | −.55 | −7.07*** | |||

| BSD | −.10 | −1.05 | BSD | .04 | 0.41 | |||

| IPDE | .24 | 2.91** | IPDE | .22 | 2.64** | |||

| 3 | BDI | −.07 | −0.78 | .04** | BDI | −.01 | −0.13 | .03** |

| HMI | .03 | 0.43 | HMI | <.01 | 0.01 | |||

| CSQ Total | .44 | 5.69*** | CSQ Total | −.56 | −7.27*** | |||

| BSD | −.02 | −0.22 | BSD | .11 | 1.13 | |||

| IPDE | −.15 | −0.92 | IPDE | −.13 | −0.83 | |||

| BSD × IPDE | .42 | 2.79** | BSD × IPDE | .37 | 2.52* | |||

| Extreme Negative Dysfunctional Attitudes | Extreme Positive Dysfunctional Attitudes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step | Variable | β | t | ΔR2 | Variable | β | t | ΔR2 |

| 1 | BDI | .06 | 0.75 | .09** | BDI | .10 | 1.66 | .52*** |

| HMI | .03 | 0.42 | HMI | .01 | 0.25 | |||

| DAS Total | .27 | 3.19** | DAS Total | −.75 | −12.22*** | |||

| 2 | BDI | .04 | 0.39 | .01 | BDI | .11 | 1.52 | .01 |

| HMI | .03 | 0.43 | HMI | .02 | 0.34 | |||

| DAS Total | .25 | 2.92** | DAS Total | −.75 | −11.80*** | |||

| BSD | −.02 | −0.21 | BSD | −.08 | −1.08 | |||

| IPDE | .10 | 1.12 | IPDE | .09 | 1.33 | |||

| 3 | BDI | .01 | 0.15 | .03* | BDI | .09 | 1.29 | .02* |

| HMI | .03 | 0.46 | HMI | .02 | 0.37 | |||

| DAS Total | .25 | 2.93** | DAS Total | −.75 | −11.98*** | |||

| BSD | .04 | 0.34 | BSD | −.04 | −0.51 | |||

| IPDE | −.20 | −1.20 | IPDE | −.13 | 1.07 | |||

| BSD × IPDE | .34 | 2.17* | BSD × IPDE | .24 | 2.15* | |||

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Note: BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; HMI = Halberstadt Mania Inventory; CSQ = Cognitive Style Questionnaire; BSD = bipolar spectrum disorder diagnosis; IPDE = International Personality Disorder Examination sum score; DAS = Dysfunctional Attitude Scale.

Figure 1.

Interactions between bipolar spectrum disorder (BSD) status and personality disorder characteristics predicting (a) extreme pessimistic attributions, (b) extreme optimistic attributions, (c) extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes, and (d) extreme positive dysfunctional attitudes.

Similarly, BSD status interacted with the IPDE total score to predict extreme optimistic attributions (Table 2; Figure 1b), such that there was a significant association between personality disorder characteristics and extreme optimistic attributions among individuals with BSDs (t = 3.59, p < .001), but not among healthy controls (t = −0.83, p = .41). This interaction was significant in the same directions using the borderline (t = 2.33, p = .02) and histrionic (t = 2.47, p = .01) subscales of the IPDE, but not for the dependent subscale (t = 1.58, p = .12).

BSD status also interacted with the IPDE total score to predict extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes (Table 2; Figure 1c), such that there was a significant relationship between personality disorder characteristics and extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes among individuals with BSDs (t = 2.13, p = .03), but not among healthy controls (t = −1.20, p = .23). However, none of the post-hoc analyses of interactions using IPDE subscales were significant.

Similarly, BSD status interacted with the IPDE total score to predict extreme positive dysfunctional attitudes (Table 2; Figure 1d), such that there was a significant association between personality disorder characteristics and extreme positive dysfunctional attitudes among individuals with BSDs (t = 2.29, p = .02), but not among healthy controls (t = −1.07, p = .29). However, none of the post-hoc analyses of interactions using IPDE subscales were significant.

Hypothesis 2: Do Extreme Cognitions Predict the Prospective Onset of Mood Episodes?

The prospective onset of episodes of depression was significantly predicted by extreme pessimistic attributions (OR = 1.05, p < .01), and extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes (OR = 1.17, p < .01), but not by extreme optimistic attributions (OR = 1.01, p = .44) or extreme positive dysfunctional attitudes (OR = 0.97, p = .31). Similarly, the prospective onset of episodes of hypomania was significantly predicted by extreme pessimistic attributions (OR = 1.06, p < .01), and extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes (OR = 1.11, p = .04), but not by extreme optimistic attributions (OR = 0.99, p = .70) or extreme positive dysfunctional attitudes (OR = 0.96, p = .25).

Table 3 displays analyses with extreme cognitions predicting episodes of depression and hypomania after controlling for general cognitive styles. When accounting for overall negative cognitive style, extreme pessimistic attributions continued to significantly predict the onset of depression; extreme optimistic attributions predicted the onset of depression at a trend level (p = .09). When accounting for overall dysfunctional attitudes, extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes predicted the onset of depression at a trend level (p = .06); extreme positive dysfunctional attitudes continued not to predict the onset of depression.

Table 3.

Extreme Cognitions Predicting the Prospective Onset of Episodes of Depression and Hypomania, after Accounting for General Cognitive Styles.

| Predicting Depression | Predicting Hypomania | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step | Variable | Wald | OR | 95% CI | ΔR2 | Wald | OR | 95% CI | ΔR2 |

| Extreme Pessimistic Attributions | |||||||||

| 1 | BDI | 3.53 | 1.04† | 1.00-1.09 | .14 | 1.27 | 1.03 | 0.98-1.08 | .36 |

| HMI | 0.03 | 1.00 | 0.95-1.05 | 0.83 | 0.97 | 0.91-1.04 | |||

| Time in Study | 0.45 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 7.78 | 1.00** | 1.00-1.00 | |||

| CSQ Total | 4.96 | 1.48* | 1.05-2.09 | 14.49 | 2.53*** | 1.57-4.08 | |||

| 2 | BDI | 4.19 | 1.05* | 1.00-1.10 | .04 | 1.53 | 1.03 | 0.98-1.09 | .01 |

| HMI | 0.07 | 0.99 | 0.94-1.05 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 0.91-1.03 | |||

| Time in Study | 0.48 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 7.90 | 1.00** | 1.00-1.00 | |||

| CSQ Total | 0.49 | 1.16 | 0.77-1.74 | 6.98 | 2.11** | 1.21-3.66 | |||

| Extreme Pessimistic (CSQ) | 4.22 | 1.05* | 1.00-1.10 | 1.51 | 1.03 | 0.98-1.09 | |||

| Extreme Optimistic Attributions | |||||||||

| 1 | BDI | 3.53 | 1.04† | 1.00-1.09 | .14 | 1.27 | 1.03 | 0.98-1.08 | .36 |

| HMI | 0.03 | 1.00 | 0.95-1.05 | 0.83 | 0.97 | 0.91-1.04 | |||

| Time in Study | 0.45 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 7.78 | 1.00** | 1.00-1.00 | |||

| CSQ Total | 4.96 | 1.48* | 1.05-2.09 | 14.49 | 2.53*** | 1.57-4.08 | |||

| 2 | BDI | 3.18 | 1.04† | 1.00-1.09 | .03 | 1.18 | 1.03 | 0.98-1.08 | .02 |

| HMI | 0.07 | 0.99 | 0.94-1.05 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.91-1.03 | |||

| Time in Study | 0.46 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 7.87 | 1.00** | 1.00-1.00 | |||

| CSQ Total | 7.35 | 1.69** | 1.16-2.48 | 15.63 | 2.89*** | 1.71-4.90 | |||

| Extreme Optimistic (CSQ) | 2.80 | 1.03† | 1.00-1.06 | 2.17 | 1.03 | 0.99-1.07 | |||

| Extreme Negative Dysfunctional Attitudes | |||||||||

| 1 | BDI | 4.80 | 1.06* | 1.01-1.11 | .17 | 5.98 | 1.07 | 1,01-1.13 | .23 |

| HMI | 0.02 | 1.00 | 0.95-1.06 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.90-1.04 | |||

| Time in Study | 1.60 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 6.60 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | |||

| DAS Total | 5.57 | 1.01* | 1.00-1.03 | 2.19 | 1.01 | 1.00-1.02 | |||

| 2 | BDI | 4.42 | 1.06* | 1.00-1.11 | .03 | 5.85 | 1.07* | 1.01-1.13 | <.01 |

| HMI | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.95-1.06 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.90-1.04 | |||

| Time in Study | 1.47 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 6.52 | 1.00* | 1.00-1.00 | |||

| DAS Total | 2.87 | 1.01† | 1.00-1.02 | 1.40 | 1.01 | 0.99-1.02 | |||

| Extreme Negative (DAS) | 3.50 | 1.15† | 0.99-1.34 | 0.31 | 1.04 | 0.90-1.21 | |||

| Extreme Positive Dysfunctional Attitudes | |||||||||

| 1 | BDI | 4.80 | 1.06* | 1.01-1.11 | .17 | 5.98 | 1.07 | 1.01-1.13 | .23 |

| HMI | 0.02 | 1.00 | 0.95-1.06 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.90-1.04 | |||

| Time in Study | 1.60 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 6.60 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | |||

| DAS Total | 5.57 | 1.01* | 1.00-1.03 | 2.19 | 1.01 | 1.00-1.02 | |||

| 2 | BDI | 4.40 | 1.06* | 1.00-1.11 | .01 | 5.95 | 1.07 | 1.01-1.13 | <.01 |

| HMI | 0.03 | 1.00 | 0.95-1.06 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.90-1.04 | |||

| Time in Study | 1.74 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 6.56 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | |||

| DAS Total | 5.46 | 1.02* | 1.00-1.04 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.99-1.02 | |||

| Extreme Positive (DAS) | 0.91 | 1.04 | 0.96-1.12 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.91-1.09 | |||

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Note. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; HMI = Halberstadt Mania Inventory; CSQ = Cognitive Style Questionnaire; DAS = Dysfunctional Attitude Scale.

When accounting for overall negative cognitive style, extreme pessimistic attributions no longer significantly predicted the onset of hypomania; extreme optimistic attributions also did not predict the onset of hypomania. Similarly, when accounting for overall dysfunctional attitudes, extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes no longer predicted the onset of hypomania; extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes continued not to predict the onset of hypomania.

Discussion

Our results indicate that extreme cognitive styles are highest among people with BSDs in conjunction with personality disorder characteristics. Among individuals with BSDs, personality disorder characteristics predicted more extreme responses on both measures of cognitive style (negative cognitive style and dysfunctional attitudes), regardless of the valence of the cognitions (optimistic-pessimistic or positive-negative). The importance of understanding characteristics associated with extreme cognitions is underscored by the fact that extreme negative cognitions also were linked to the future occurrence of episodes of depression and hypomania. Our study provides further evidence that extreme negative cognitive styles may be maladaptive, and extends this research to individuals with BSDs. Given that previous research has linked extreme cognitions to the onset of mood episodes in MDD and BD (Beevers et al., 2003; Forand & DeRubeis, 2014; Petersen et al., 2007; Stange et al., 2013a,b; Teasdale et al., 2001), results that were partially replicated in the present study, these results suggest that one reason that individuals with BSDs and personality disorders are vulnerable to experiencing mood episodes may be that these individuals tend to exhibit extreme cognitions.

Consistent with prior studies of cognitive style in BDs (see Alloy et al., 2005), individuals with BSDs had more negative cognitive styles and more dysfunctional attitudes than did healthy controls. However, this study is the first to compare extreme cognitions in individuals with BSDs to healthy control participants, and found that extreme pessimistic attributions, but not extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes, were higher in individuals with BSDs.

Furthermore, it was individuals with the combination of BSD and elevated personality disorder characteristics who had the most extreme cognitive styles. Importantly, these analyses accounted for individuals’ levels of general negative cognitive styles as typically evaluated on the CSQ and DAS, indicating that personality disorder characteristics were associated specifically with extreme cognitive styles in BSDs, rather than with negative cognitive styles in general. This suggests that personality disorder comorbidity may help to explain which individuals with BSDs have extreme cognitions, but that comorbidity is not simply associated with more negative cognitions overall. Borderline and histrionic characteristics were associated with more extreme pessimistic and more extreme optimistic attributions in BSDs, suggesting that these individuals’ cognitive styles may be consistent with the extremely dramatic and emotional traits that characterize these disorders (e.g., the black-and-white thinking that characterizes borderline personality; e.g., Mak & Lam, 2013). In contrast, dependent personality disorder characteristics were associated only with extreme pessimistic attributions in BSDs, which may be consistent with these individuals’ tendency to have negative self-schemas and therefore to hold extreme maladaptive beliefs about competence (Beck et al., 2006). It is possible that the tendency to hold extreme negative cognitions may be part of a broader cognitive style of inflexibly responding to the world that characterizes personality disorders (e.g., Lenzenweger & Clarkin, 2005).

Unexpectedly, we also found that BSD participants had less extreme positive dysfunctional attitudes relative to controls, and that these extreme positive dysfunctional attitudes did not predict the onset of mood episodes. Although extreme dysfunctional attitudes have not previously been evaluated in BSDs, these results contrast with studies of MDD that found that extreme positive dysfunctional attitudes predicted the recurrence of depressive episodes (Forand & DeRubeis, 2014; Petersen et al., 2007). Although the reason for the discrepancy between these studies is unclear, it could be that “extreme positive” dysfunctional attitudes (as measured by the DAS) generally do not truly indicate the presence of extreme beliefs but rather represent a lack of maladaptive beliefs (e.g., Forand & DeRubeis, 2014). In our sample, extreme optimistic and extreme pessimistic attributions were moderately correlated, whereas extreme positive and extreme negative responses on the DAS were not significantly correlated. This suggests that although endpoints of these scales may capture some shared component of cognitive extremity or rigidity, they may not represent a unitary construct; our data suggest that extreme negative responses may be most maladaptive in BSDs. Nevertheless, future research should use additional measures and methods to examine the role of extreme positive cognitions in the course of illness in BSDs and personality disorders (e.g., Dodd et al., 2011).

Consistent with data from individuals with bipolar I or II disorder from STEP-BD (Stange et al., 2013b), individuals who made more extreme negative attributions were more likely to experience a prospective onset of an episode of hypomania. In addition, ours is the first study to demonstrate that extreme pessimistic attributions are associated with a greater likelihood of the onset of a major depressive episode among a sample containing individuals with BSDs. Along with results from STEP-BD indicating that extreme attributions predicted longer duration of current episodes (Stange et al., 2013a), our results indicate that understanding the determinants of extreme negative cognitions may be important because they have implications for understanding the course of illness in BSDs.

Our study is also the first to evaluate extreme dysfunctional attitudes in BSDs. Consistent with previous studies of unipolar depression that found that extreme dysfunctional attitudes predicted depressive relapse (Beevers et al., 2003; Forand & DeRubeis, 2014; Petersen et al., 2007; Teasdale et al., 2001), in our sample, extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes predicted a greater likelihood of experiencing an onset of major depression. Extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes also predicted the onset of episodes of hypomania. Given the moderate to strong correlation between extreme pessimistic attributions and extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes, these results suggest that extreme negative responding on measures of cognitive style in general in BSDs may be indicative of susceptibility to mood dysregulation, regardless of the valence of the moods.

Although extreme pessimistic attributions and extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes predicted the prospective onset of episodes of depression and hypomania, some of these relationships were attenuated when accounting for general cognitive styles. When testing extreme pessimistic attributions and general negative cognitive style in models simultaneously, only extreme pessimistic attributions predicted the onset of depression, but only general negative cognitive style predicted the onset of hypomania. This could suggest that the extremity of pessimistic attributions could confer particular vulnerability to depression in BSDs, whereas extreme pessimistic attributions are likely to lead to hypomania as a result of the general negativity, as opposed to the extremity, of the style. However, given that extreme pessimistic attributions (but not general negative cognitive style) conferred risk for mania in bipolar I disorder (Stange et al., 2013b), these results will need to be replicated before firm conclusions can be drawn. Similarly, when testing extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes and general dysfunctional attitudes in models simultaneously, extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes predicted the onset of depression only at a trend level, whereas extreme negative dysfunctional attitudes no longer predicted the onset of hypomania. Thus, our data provide somewhat less support for extreme dysfunctional attitudes in providing additional risk for mood episodes beyond that conferred by general dysfunctional attitudes. Still, it is important to note that the majority of previous studies that have evaluated the association between extreme cognitions and mood episodes have not accounted for general negative cognitive styles in statistical analyses. Given that ruling out alternative plausible explanations will be important in determining whether extreme cognitions serve as vulnerability factors (e.g., Riskind & Alloy, 2006), our controlling for general negative cognitive styles is an important strength of the current study.

This study is an early step in understanding the characteristics associated with people who make extreme attributions and/or who hold extreme beliefs. However, we know little about what extreme responses on these cognitive measures represent. Previous studies have found that extreme response styles on other self-report measures are associated with intolerance of ambiguity, cognitive inflexibility, simplistic thinking, and taking a shorter time to complete measures (Hamilton, 1968; Naemi, Beale, & Payne, 2009). These findings are consistent with the notion that extreme responses on cognitive measures may represent relatively automatic schematic processing that is uncorrected by deliberate reappraisal in more moderate terms (e.g., Gilbert, 1989; Teasdale et al., 2001). They also indicate that extreme responses may represent an all-or-nothing, rigid way of responding to the environment.

It is not yet clear precisely why extreme cognitions are associated with the occurrence of mood episodes. Stress generation has been proposed as a mechanism by which individuals with mood disorders or cognitive vulnerabilities shape their own environments and contribute to the occurrence of stressful events (Bender et al., 2010; Hammen, 1991; Safford et al, 2007). It is likely that individuals who have extreme cognitions generate distress in interpersonal relationships with these cognitions (Hamilton et al., 2013; Safford et al., 2007); these ensuing stressful events are likely to impact the mood state of the individual (e.g., Johnson, 2005; Johnson & Roberts, 1995). Cognitive inflexibility, or the reluctance to change beliefs or attitudes or to perseverate in mental acts, is also elevated in bipolar disorder and could result in a poorer course of illness as a result of difficulty disengaging from negative patterns of thought (e.g., Joormann & Siemer, 2011). It is possible that extreme cognitions are associated with cognitive inflexibility, although we did not evaluate this proposition in this study. Similarly, endorsing extreme or inflexible cognitions could signify an inability to modify coping styles in the face of difficult life events, thereby leading to affective changes (Cheng, 2001; Fresco et al., 2007a).

Although preliminary, these results may have implications for the treatment of individuals with BSDs. First, modifying extreme negative cognitions might be helpful in improving the course of BSDs. In line with this suggestion, changes to extreme dysfunctional attitudes have been shown to mediate progress in cognitive therapy for unipolar depression (Petersen et al., 2007; Teasdale et al., 2001). Thus, patients with BSDs may benefit from therapies that focus on restructuring of extreme thoughts and beliefs, and that facilitate achieving cognitive distance so as to reduce the impact of extreme cognitions. It is possible that patients who have extreme cognitions could also benefit from treatments involving mindful detachment from and observing of thoughts rather than assuming their accuracy (e.g., Deckersbach et al., 2012; Fresco et al., 2007b). These targets of treatment may prove especially helpful among individuals with BSDs who also exhibit personality disorder characteristics, as these individuals may be the most likely to have these extreme cognitions and to experience more frequent and/or more severe mood episodes.

It is important to note that we did not diagnose personality disorders in this sample, but rather used a continuous measure of these characteristics, so the implications for more severe, diagnosable personality disorders are unclear. It is possible that using a continuous sum score of personality disorder characteristics across multiple types of personality pathology made it difficult to differentiate between individuals with a personality disorder in one domain but few symptoms in another, from individuals with no identifiable personality disorder but who possess a profile of symptoms in each of several personality disorder areas. In addition, we evaluated personality disorder characteristics but did not utilize a comparison group of BSD participants with non-personality disorder comorbid psychopathology, so it is unclear to what extent these results may be specific to BSD and personality disorder comorbidity versus to comorbidity in general. Similarly, our sample includes individuals on the bipolar spectrum so it is unclear whether these results also apply for individuals with bipolar I disorder. Several factors may have led us to underestimate associations between extreme optimistic or positive cognitions and the onset of mood episodes, including excluding individuals with bipolar I, not conducting prospective analyses in the BSD group exclusively, left- and right-censoring and relatively low base-rate of mood episodes, not examining bipolar subgroups (i.e., bipolar II, bipolar NOS, and cyclothymia) separately, not evaluating associations with specific treatments such as exposure to cognitive therapy, and using self-reported measures of cognitive styles. Complimentary future studies might follow individuals more intensively and use event history models to predict progression or relapse of mood episodes.

Next, it is also important to acknowledge that several of our measures (e.g., personality disorder characteristics and cognitive styles) were evaluated at the same time point, which prevented us from evaluating potential mediational relationships between the variables tested. The study also may have been limited by relatively low inter-rater reliabilities on the IPDE, and by calculating reliability based on re-ratings of original interviews rather than by independently-administered interviews. Next, more work demonstrating the construct validity and psychometric properties (e.g., retest reliability) of measures of cognitive extremity as assessed by the DAS and CSQ also is needed. Finally, it is unclear whether extreme cognitions reported on questionnaires accurately reflect how people actually think in response to stressors. Future research evaluating extreme attributions should include event-specific inferences for actual events that happened in participants’ lives.

In sum, the present study indicates that personality disorder characteristics may exacerbate the tendency for individuals with BSDs to have extreme cognitions, and it corroborates evidence for the utility of evaluating extreme cognitions in understanding the course of mood disorders. Future research should examine what extreme cognitive responses on self-report measures represent in real life, and should examine mechanisms underlying these relationships among clinical samples of individuals with BSDs and comorbid personality disorders. Although this study is one of the first to examine correlates of extreme cognitions, it suggests that when it comes to cognition, the “middle path” may be most adaptive.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIMH grants 52617 and 77908 to Lauren B. Alloy and 52662 to Lyn Y. Abramson. Jonathan P. Stange was supported by National Research Service Award F31MH099761 from NIMH.

Footnotes

These criteria for bipolar NOS are relevant to the DSM-5 criteria for other specified bipolar and related disorders, which allow for a diagnosis of a bipolar disorder in individuals who otherwise meet criteria for hypomania except for the duration criterion or the number of symptoms required.

Contributor Information

Jonathan P. Stange, Temple University

Ashleigh Molz Adams, Temple University.

Jared K. O'Garro-Moore, Temple University

Rachel B. Weiss, McLean Hospital and Harvard Medical School

Mian-Li Ong, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Patricia D. Walshaw, UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior

Lyn Y. Abramson, University of Wisconsin, Madison

Lauren B. Alloy, Temple University

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Akiskal HS, Djenderedjian AH, Rosenthal RH, Khani MK. Cyclothymic disorder: validating criteria for inclusion in the bipolar affective group. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1977;134:1227–1233. doi: 10.1176/ajp.134.11.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Reilly-Harrington N, Fresco DM, Whitehouse WG, Zechmeister JS. Cognitive styles and life events in subsyndromal unipolar and bipolar disorders: Stability and prospective prediction of depressive and hypomanic mood swings. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1999;13(1):21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Hogan ME, Whitehouse WG, Rose DT, Robinson MS, Lapkin JB. The Temple-Wisconsin Cognitive Vulnerability to Depression Project: lifetime history of axis I psychopathology in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109(3):403–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Urosevic S, Walshaw PD, Nusslock R, Neeren AM. The psychosocial context of bipolar disorder: Environmental, cognitive, and developmental risk factors. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25(8):1043–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Walshaw PD, Cogswell A, Grandin LD, Hughes ME, Hogan ME. Behavioral Approach System and Behavioral Inhibition System sensitivities and bipolar spectrum disorders: prospective prediction of bipolar mood episodes. Bipolar Disorders. 2008;10(2):310–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Walshaw PD, Gerstein RK, Keyser JD, Whitehouse WG, Harmon-Jones E. Behavioral approach system (BAS)–relevant cognitive styles and bipolar spectrum disorders: Concurrent and prospective associations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118(3):459–471. doi: 10.1037/a0016604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Urošević S, Abramson LY, Jager-Hyman S, Nusslock R, Whitehouse WG, Hogan M. Progression along the bipolar spectrum: A longitudinal study of predictors of conversion from bipolar spectrum conditions to bipolar I and II disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121(1):16–27. doi: 10.1037/a0023973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th Ed. APA; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision. 4th Ed. APA; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Angst F, Stassen HH, Clayton PJ, Angst J. Mortality of patients with mood disorders: follow-up over 34–38 years. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002;68(2):167–181. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arntz A. Treatment of borderline personality disorder: a challenge for cognitive-behavioural therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1994;32(4):419–430. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Freeman A, Davis DD. Cognitive therapy of personality disorders. Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, editor. Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8(1):77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Beevers CG, Keitner GI, Ryan CE, Miller IW. Cognitive predictors of symptom return following depression treatment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112(3):488–496. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender RE, Alloy LB, Sylvia LG, Uroševic S, Abramson LY. Generation of life events in bipolar spectrum disorders: A re-examination and extension of the stress generation theory. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2010;66(9):907–926. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieling PJ, MacQueen GM, Marriot MJ, Robb JC, Begin H, Joffe RT, Young LT. Longitudinal outcome in patients with bipolar disorder assessed by life-charting is influenced by DSM-IV personality disorder symptoms. Bipolar Disorders. 2003;5(1):14–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein B, Strober M, Gill MK, Hunt J, Keller M. Four-year longitudinal course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorder: The course and outcome of bipolar youth (COBY) study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166(7):795–804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08101569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buddhist Publication Society [30 June 2013];“The Book of Protection: Paritta”, translated from the original Pali, with introductory essay and explanatory notes by PiyadassiThera. 1999 http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/piyadassi/protection.html.

- Bumberry W, Oliver JM, McClure JN. Validation of the Beck Depression Inventory in a university population using psychiatric estimate as the criterion. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1978;46(1):150–155. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C. Assessing coping flexibility in real-life and laboratory settings: a multimethod approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80(5):814–833. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.80.5.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogswell A, Alloy LB. The relation of neediness and Axis II pathology. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2006;20(1):16–21. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2006.20.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckersbach T, Hölzel BK, Eisner LR, Stange JP, Peckham AD, Dougherty DD, Nierenberg AA. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Nonremitted Patients with Bipolar Disorder. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 2012;18(2):133–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2011.00236.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Iacono WG. Neurobehavioral aspects of affective disorders. Annual Review of Psychology. 1989;40(1):457–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.40.020189.002325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Krauss S, Spoont MR, Arbisi P. General Behavior Inventory identification of unipolar and bipolar affective conditions in a nonclinical university population. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1989;98(2):117–126. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.98.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Slater JF, Wolfstetter-Kausch H, Klein D, Goplerud E, Farr D. A behavioral paradigm for identifying persons at risk for bipolar depressive disorder: a conceptual framework and five validation studies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1981;90(5):381–437. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.90.5.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd AL, Mansell W, Morrison AP, Tai S. Extreme appraisals of internal states and bipolar symptoms: The Hypomanic Attitudes and Positive Predictions Inventory. Psychological Assessment. 2011;23(3):635–645. doi: 10.1037/a0022972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunayevich E, Sax KW, Keck PE, Jr, McElroy SL, Sorter MT, McConville BJ, Strakowski SM. Twelve-month outcome in bipolar patients with and without personality disorders. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2000;61(2):134–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Spitzer RL. A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1978;35(7):837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770310043002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan AH, Hassell J. Bipolar disorder and comorbid personality psychopathology: a review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69(11):1794–1803. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forand NR, DeRubeis RJ. Extreme response style and symptom return after depression treatment: The role of positive extreme responding. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0035755. doi: 10.1037/a0035755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis-Raniere EL, Alloy LB, Abramson LY. Depressive personality styles and bipolar spectrum disorders: Prospective tests of the event congruency hypothesis. Bipolar Disorders. 2006;8(4):382–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresco DM, Rytwinski NK, Craighead LW. Explanatory flexibility and negative life events interact to predict depression symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2007;26(5):595–608. [Google Scholar]

- Fresco DM, Segal ZV, Buis T, Kennedy S. Relationship of posttreatment decentering and cognitive reactivity to relapse in major depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(3):447–455. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George EL, Miklowitz DJ, Richards JA, Simoneau TL, Taylor DO. The comorbidity of bipolar disorder and axis II personality disorders: prevalence and clinical correlates. Bipolar Disorders. 2003;5(2):115–122. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DT. Thinking lightly about others: Automatic components of the social inference process. In: Uleman JS, Bargh JA, editors. Unintended thought. Guilford Press; New York: 1989. pp. 189–211. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness. Oxford University Press; NY: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeffel GJ, Gibb BE, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Hankin BL, Swendsen JD. Measuring cognitive vulnerability to depression: Development and validation of the cognitive style questionnaire. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(5):824–836. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt LJ, Abramson LY. The Halberstadt Mania Inventory (HMI) University of Wisconsin; Madison, WI: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton DL. Personality attributes associated with extreme response style. Psychological Bulletin. 1968;69(3):192–203. doi: 10.1037/h0025606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JL, Stange JP, Shapero BG, Connolly SL, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Cognitive vulnerabilities as predictors of stress generation in early adolescence: Pathway to depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41(7):1027–1039. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9742-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen CL. Depression in college students: beyond the Beck Depression Inventory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1980;48(1):126. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.48.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(4):555–561. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway SR, McKinley JC. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory; manual (Revised) 1951. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL. Life events in bipolar disorder: towards more specific models. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25(8):1008–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Fingerhut R. Negative cognitions predict the course of bipolar depression, not mania. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2004;18(2):149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Meyer B. Psychosocial predictors of symptoms. In: Johnson SL, Leahy RL, editors. Psychological Treatment of Bipolar Disorder. Guilford Press; NY: 2005. pp. 83–108. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Roberts JE. Life events and bipolar disorder: implications from biological theories. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(3):434–449. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Mansell W, Waller L. Appraisal of hypomania-relevant experiences: Development of a questionnaire to assess positive self-dispositional appraisals in bipolar and behavioural high risk samples. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;93(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, Siemer M. Affective processing and emotion regulation in dysphoria and depression: cognitive biases and deficits in cognitive control. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2011;5(1):13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Akiskal HS. The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2003;73(1):123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Solomon DA, Maser JD, Coryell W, Endicott J, Akiskal HS. Psychosocial disability and work role function compared across the long-term course of bipolar I, bipolar II and unipolar major depressive disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008;108(1):49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RE, Mansell W, Wood AM, Alatiq Y, Dodd A, Searson R. Extreme positive and negative appraisals of activated states interact to discriminate bipolar disorder from unipolar depression and non-clinical controls. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;134(1):438–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Depue RA, Slater JF. Cyclothymia in the adolescent offspring of parents with bipolar affective disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1985;94(2):115. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.94.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzenweger MF, Clarkin JF, editors. Major theories of personality disorders. Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Loranger AW. Dependent personality disorder: Age, sex, and Axis I comorbidity. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1996;184(1):17–21. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199601000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansell W, Morrison AP, Reid G, Lowens I, Tai S. The interpretation of, and responses to, changes in internal states: An integrative cognitive model of mood swings and bipolar disorders. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2007;35(5):515–539. [Google Scholar]

- Mansell W, Paszek G, Seal K, Pedley R, Jones S, Thomas N, Dodd A. Extreme appraisals of internal states in bipolar I disorder: A multiple control group study. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2011;35(1):87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Naemi BD, Beal DJ, Payne SC. Personality predictors of extreme response style. Journal of Personality. 2009;77(1):261–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nierenberg AA, Akiskal HS, Angst J, Hirschfeld RM, Merikangas KR, Petukhova M, Kessler RC. Bipolar disorder with frequent mood episodes in the national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R). Molecular Psychiatry. 2009;15(11):1075–1087. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, Marangell LB, Zhang H, Wisniewski SR, Ketter TA, Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Gyulai L, Reilly-Harrington NA, Nierenberg AA, Sachs GS, Thase ME. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(2):217–224. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson TJ, Feldman G, Harley R, Fresco DM, Graves L, Holmes A, Segal ZV. Extreme response style in recurrent and chronically depressed patients: Change with antidepressant administration and stability during continuation treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(1):145–153. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkonis PA, Heape CL, Ruddy J, Serrao P. Validity in the diagnosis of personality disorders: The use of the LEAD standard. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;3(1):46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly-Harrington NA, Alloy LB, Fresco DM, Whitehouse WG. Cognitive styles and life events interact to predict bipolar and unipolar symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108(4):567–578. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.4.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riskind JH, Alloy LB. Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders: Theory and research design/methodology. In: Alloy LB, Riskind JH, editors. Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Safford SM, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Crossfield AG. Negative cognitive style as a predictor of negative life events in depression-prone individuals: A test of the stress generation hypothesis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;99(1):147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E. Research Diagnostic Criteria: rationale and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1978;35(6):773. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300115013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II) New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York, NY: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Stange JP, Sylvia LG, Magalhaes PV, Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Frank E, Deckersbach T. Extreme attributions predict the course of bipolar depression: results from the STEP-BD randomized controlled trial of psychosocial treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2013a;74(3):249–255. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stange JP, Sylvia LG, Magalhães PV, Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Frank E, Berk M, Hansen NS, Dougherty DD, Nierenberg AA, Deckersbach T. Extreme attributions predict suicide ideation and attempts in bipolar disorder: Prospective data from STEP-BD. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):95–96. doi: 10.1002/wps.20093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stange JP, Sylvia LG, Magalhães PVDS, Frank E, Otto MW, Miklowitz DJ, Deckersbach T. Extreme attributions predict transition from depression to mania or hypomania in bipolar disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2013b;47(10):1329–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale JD, Scott J, Moore RG, Hayhurst H, Pope M, Paykel ES. How does cognitive therapy prevent relapse in residual depression? Evidence from a controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(3):347–357. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman A, Beck AT. Development and validation of the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale: A preliminary investigation.. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Educational Research Association; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. 1978, November. [Google Scholar]