Abstract

Background

Despite the increasing number of reports of autochthonous cases of ocular thelaziosis in dogs in several European countries, and the evident emergence of human cases, the distribution and spreading potential of this parasite is far for being fully known. In Romania, despite intensive surveillance performed over recent years on the typical hosts of T. callipaeda, the parasite has not been found until now.

Methods

In October 2014 a German Shepherd was presented for consultation to a private veterinary practice from western Romania with a history of unilateral chronic conjunctivitis. Following a close examination of the affected eye, nematodes were noticed in the conjunctival sac. The specimens collected were used for morphological examination (light microscopy) and molecular analysis (amplification of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene, followed by sequencing).

Results

Thirteen nematodes were collected, all identified morphologically as T. callipaeda. The history of the dog revealed no travel outside Romania, and during the last year, not even outside the home locality. The BLAST analysis of our sequence showed a 100% similarity T. callipaeda haplotype h1.

Conclusions

This is the first report of T. callipaeda in Romania, which we consider to be with autochthonous transmission. These findings confirm the spreading trend of T callipaeda and the increased risk of emerging vector-borne zoonoses.

Keywords: Thelazia callipaeda, Emerging disease, Canine vector-borne diseases

Background

Thelazia callipaeda is a vector-borne zoonotic eyeworm, parasitizing the conjunctival sac of domestic and wild carnivores (foxes, beech martens and wolves), rabbits and humans. Its presence is associated with mild to severe ocular disease [1,2]. The distribution includes vast territories in Asia (hence the name “oriental eye worm”) but also in former Soviet Union [3]. In Europe, the first report came from Italy [4] followed by various subsequent records in the same country [5-7]. However, during the last decade, the knowledge about its distribution in Europe has been greatly expanded (Table 1). The vector was demonstrated by Otranto et al. [8,9], when the nematodes were successfully transmitted by the drosophilid fly, Phortica variegata (Drosophilidae, Steganinae).

Table 1.

Emergence of Thelazia callipaeda in Europe between 2007 and 2014

All the T. callipaeda isolates in Europe for which sequences of partial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) are available belong to the haplotype 1 (h1), suggesting a high degree of nematode-host affiliations for this haplotype [15].

Based on climatic analysis, a wider European distribution was suggested already in 2003 by Otranto et al. [7]. Despite our recent intensive surveillance on vector-borne diseases of wild (foxes, jackals, wolves, wild cats, lynxes) and domestic carnivores (dogs, cats) in Romania [16-24], until now we were not able to confirm the presence of this zoonotic helminth in Romania.

The aim of this study was to extend the knowledge on the geographical distribution of T. callipaeda in Europe and to identify the haplotype circulating in Romania.

Methods

In October 2014, a dog (German Shepherd x Siberian Husky cross breed, castrated male, 9 years old) was presented for consultation to a private veterinary practice from Oradea, Bihor County, in western Romania (47.06 N, 21.90E) with a history of unilateral chronic conjunctivitis (right eye). After one month of local intra-conjunctival treatment with antibiotics, as the animal’s condition was not improving, the owner brought the case to our attention (by author RC). Following a close examination of the affected eye, alive, white, medium-sized nematodes were noticed in the conjunctival sac. As part of the treatment, all nematodes were collected during superficial anaesthesia (Xylazine + Ketamine), using a fine blunt tweezers and preserved for further examination in absolute ethanol (3 specimens) and 5% formalin (10 specimens). We have obtained the verbal consent of the owner to use the collected material for a scientific publication and he kindly provided the travel history of the dog.

The specimens collected in formalin were used for morphological examination. The nematodes were mounted on a glass slide, cleared with lactophenol and examined using an Olympus BX61 microscope. Photographs and measurements for morphologic identification were taken using a DP72 camera and Cell^F software (Olympus Corporation, Japan).

The specimens collected in absolute ethanol were analysed using molecular techniques. Genomic DNA was extracted from a gravid female using a commercial kit (Isolate II Genomic DNA Kit, BIOLINE, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Amplification of a partial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) gene of spirurid nematodes (670 bp) was performed using the NTF/NTR primer pair, following reaction procedures and protocols described in literature [25]. PCR products were visualized by electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel stained with RedSafeTM 20000× Nucleic Acid Staining Solution (Chembio, UK) and their molecular weight was assessed by comparison to a molecular marker (O’GeneRulerTM 100 bp DNA Ladder, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA). Amplicons were purified using silica-membrane spin columns (QIAquick PCR Purification Kit, Quiagen) and then sequenced (performed at Macrogen Europe, Amsterdam). Sequences were compared to those available in GenBank™ dataset by Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) analysis.

Results

From the conjunctival sac of the right eye, 12 nematodes were collected. Additionally, one nematode was also found in the conjunctival sac of the apparently non-affected left eye. A close examination of the affected right eye revealed the presence of proliferative lesions in the inferior conjunctival sac (Figure 1), epiphora and conjunctivitis. The history of the dog as recalled by the owner did not include any travel outside Romania, and in the last year, not even outside the city limits of Oradea.

Figure 1.

Clinical aspect of the infection with the presence of nematodes.

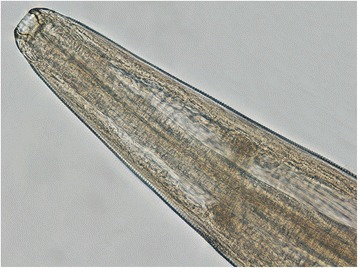

Light microscopy (Figure 2) examination of the nematodes revealed typical specific features of T. callipaeda [26]. All 13 collected nematodes were females (no males were found).

Figure 2.

Typical morphology of the anterior extremity of female T. callipaeda (x400).

The BLAST analysis of our sequence (GenBank™ accession number KP087796) showed a 100% similarity to a sequence (GenBank™ accession number AM042549) of T. callipaeda haplotype h1 [15].

Discussion

After the previous records in Europe (Italy, France, Switzerland, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia), the current study reports the presence of the zoonotic eyeworm T. callipaeda for the first time in Romania. Considering that the host dog has never travel to other known endemic areas, nor outside the city limits in the last year, we regard this as a sufficient proof for the existence of an autochthonous transmission cycle. So far, this is the most easternmost report in Europe (except previous records from the former USSR), confirming in our opinion the spread of this nematode.

Often, disease emergence and spreading, is only apparent due to lack of sufficient investigation, mainly in the case of non-clinical infections which require targeted laboratory diagnosis. However, in the case of canine ocular thelaziasis, we consider the disease new to Romania, as the infection is usually clinical and can be hardly overlooked by owners and clinicians. Moreover, in the past 5 years, the authors of the present paper had intensively focused on the surveillance of vector-borne pathogens in domestic and wild carnivores, with more than one thousand potential hosts individuals investigated and specifically examined for eye worms from various regions of the country (including western Romania). Additionally, to our knowledge, T. callipaeda was not found to date in any of the neighbouring countries (i.e. Hungary, Bulgaria, Serbia, Republic of Moldavia or Ukraine).

The only confirmed vector for T. callipaeda is Phortica variegata (Diptera, Drosophilidae, Steganinae) has been reported in Romania on various occasions [27]. Its presence is known from the following counties: Buzău, Giurgiu, Constanța, Caraș-Severin, Mehedinți, Timiș, Maramureș, Ialomița and Teleorman [27]. As Oradea (Bihor County) has similar climatic and ecologic conditions with the known area of P. variegata occurrence in Romania, the vector is also probably present here. However, further entomological surveys are required for its confirmation.

Genetic analysis of cox1 confirmed the existence in Europe of a single haplotype, as defined earlier [15], suggesting a west to east spread of the parasite in Europe. However, it is not clear which are the possible routes of disease spreading, but most probably this is related to host circulation rather that vector emergence or climate change.

Cats have been also implicated in clinical cases of ocular infections with T. callipaeda, with reports from Italy, France, Portugal and Switzerland [5,7,10,28-31]. Recent data suggest also the potential reservoir role of wildlife in natural transmission cycles of this spirurid [32-34].

Conclusion

As T. callipaeda is an emerging zoonotic infection [35], our findings bring new important epidemiological data highlighting the need for increased awareness among owners, veterinarians and ophthalmologists, even outside the known endemic areas.

Acknowledgements

The work of ADM, GA, IAM and MAI was done under the frame of EurNegVec COST Action TD1303. The financial support for the research was provided by project IDEI PCE 236/2011 (CNCS, UEFISCDI).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ADM wrote the manuscript, GD collected the nematodes and performed the morphological identification, IS and RC diagnosed the clinical case and IAM and AMI performed the molecular analysis. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Andrei Daniel Mihalca, Email: amihalca@usamvcluj.ro.

Gianluca D’Amico, Email: gianluca.damico@usamvcluj.ro.

Iuliu Scurtu, Email: icscurtu@yahoo.com.

Ramona Chirilă, Email: rpurge@yahoo.com.

Ioana Adriana Matei, Email: matei.ioana@usamvcluj.ro.

Angela Monica Ionică, Email: ionica.angela@usamvcluj.ro.

References

- 1.Otranto D, Traversa D. Thelazia eyeworm: an original endo- and ecto-parasitic nematode. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodžić A, Latrofa MS, Annoscia G, Alić A, Beck R, Lia RP, Dantas-Torres F, Otranto D. The spread of zoonotic Thelazia callipaeda in the Balkan area. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:352. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson RC. Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates: Their Development and Transmission. Guilford: CABI Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossi L, Bertaglia PP. Presence of Thelazia callipaeda Railliet & Henry, 1910, in Piedmont, Italy. Parassitologia. 1989;31:167–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Sacco B, Ciocca A, Sirtori G. Thelazia callipaeda (Railliet and Henry, 1910) nel sacco congiuntivale di un gatto di Milano. Veterinaria. 1995;4:81–84. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lia RP, Garaguso M, Otranto D, Puccini V. First report of Thelazia callipaeda in Southern Italy, Basilicata region. Acta Parasitol. 2000;45:178. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Otranto D, Ferroglio E, Lia RP, Traversa D, Rossi L. Current status and epidemiological observation of Thelazia callipaeda (Spirurida, Thelaziidae) in dogs, cats and foxes in Italy: a “coincidence” or a parasitic disease of the Old Continent? Vet Parasitol. 2003;116:315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otranto D, Lia RP, Cantacessi C, Testini G, Troccoli A, Shen JL, Wang ZX. Nematode biology and larval development of Thelazia callipaeda (Spirurida, Thelaziidae) in the drosophilid intermediate host in Europe and China. Parasitology. 2005;131:847–855. doi: 10.1017/S0031182005008395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Otranto D, Cantacessi C, Testini G, Lia RP. Phortica variegata as an intermediate host of Thelazia callipaeda under natural conditions: evidence for pathogen transmission by a male arthropod vector. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36:1167–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorchies P, Chaudieu G, Siméon LA, Cazalot G, Cantacessi C, Otranto D. First reports of autochthonous eyeworm infection by Thelazia callipaeda (Spirurida, Thelaziidae) in dogs and cat from France. Vet Parasitol. 2007;149:294–297. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malacrida F, Hegglin D, Bacciarini L, Otranto D, Nägeli F, Nägeli C, Bernasconi C, Scheu U, Balli A, Marenco M, Togni L, Deplazes P, Schnyder M. Emergence of canine ocular thelaziosis caused by Thelazia callipaeda in southern Switzerland. Vet Parasitol. 2008;157:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magnis J, Naucke TJ, Mathis A, Deplazes P, Schnyder M. Local transmission of the eye worm Thelazia callipaeda in southern Germany. Parasitol Res. 2010;106:715–717. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1678-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miró G, Montoya A, Hernández L, Dado D, Vázquez MV, Benito M, Villagrasa M, Brianti E, Otranto D. Thelazia callipaeda: infection in dogs: a new parasite for Spain. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:148. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vieira L, Rodrigues FT, Costa A, Diz-Lopes D, Machado J, Coutinho T, Tuna J, Latrofa MS, Cardoso L, Otranto D. First report of canine ocular thelaziosis by Thelazia callipaeda in Portugal. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:124. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otranto D, Testini G, De Luca F, Hu M, Shamsi S, Gasser RB. Analysis of genetic variability within Thelazia callipaeda (Nematoda: Thelazioidea) from Europe and Asia by sequencing and mutation scanning of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene. Mol Cell Probes. 2005;19:306–313. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiss T, Cadar D, Krupaci AF, Bordeanu A, Brudaşcă GF, Mihalca AD, Mircean V, Gliga L, Dumitrache MO, Spînu M. Serological reactivity to Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in dogs and horses from distinct areas in Romania. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:1259–1262. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2010.0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mircean V, Dumitrache MO, Györke A, Pantchev N, Jodies R, Mihalca AD, Cozma V. Seroprevalence and geographic distribution of Dirofilaria immitis and tick-borne infections (Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, and Ehrlichia canis) in dogs from Romania. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12:595–604. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dumitrache MO, Kiss B, Dantas-Torres F, Latrofa MS, D’Amico G, Sándor AD, Mihalca AD. Seasonal dynamics of Rhipicephalus rossicus attacking domestic dogs from the steppic region of southeastern Romania. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:97. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dumitrache MO, D’Amico G, Matei IA, Ionică A, Gherman CM, Sikó Barabási S, Ionescu DT, Oltean M, Balea A, Ilea IC, Sándor AD, Mihalca AD. Ixodid ticks in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from Romania. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7(Suppl 1):1. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-S1-P1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mircean V, Dumitrache MO, Mircean M, Bolfa P, Györke A, Mihalca AD. Autochthonous canine leishmaniasis in Romania: neglected or (re)emerging? Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:135. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ionică AM, D’Amico G, Mitková B, Kalmár Z, Annoscia G, Otranto D, Modrý D, Mihalca AD. First report of Cercopithifilaria spp. in dogs from Eastern Europe with an overview of their geographic distribution in Europe. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:2761–2764. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3931-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ionică AM, Matei IA, Mircean V, Dumitrache MO, Annoscia G, Otranto D, Modrý D, Mihalca AD. Filarial infections in dogs from Romania: a broader view. In Proceedings of Fourth European Dirofilaria and Angiostrongylus Days: 2-4 July 2014; Budapest. 1996:42.

- 23.Sándor AD, Dumitrache MO, D’Amico G, Kiss BJ, Mihalca AD. Rhipicephalus rossicus and not R. sanguineus is the dominant tick species of dogs in the wetlands of the Danube Delta, Romania. Vet Parasitol. 2014;204:430–432. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitková B, Qablan MA, Mihalca AD, Modrý D. Questing for the identity of Hepatozoon in foxes. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7(Suppl 1):O23. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-S1-O23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Casiraghi M, Anderson TJC, Bandi C, Bazzocchi C, Genchi C. A phylogenetic analysis of filarial nematodes: comparison with the phylogeny of Wolbachia endosymbionts. Parasitology. 2001;122:93–103. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000007149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otranto D, Lia RP, Traversa D, Giannetto S. Thelazia callipaeda (Spirurida, Thelaziidae) of carnivores and humans: morphological study by light and scanning electron microscopy. Parassitologia. 2003;45:125–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.TaxoDros: The database on Taxonomy of Drosophilidae. http://taxodros.uzh.ch. Accessed 12.01.2015.

- 28.Ruytoor P, Déan E, Pennant O, Dorchies P, Chermette R, Otranto D, Guillot J. Ocular thelaziosis in dogs, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1943–1945. doi: 10.3201/eid1612.100872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodrigues FT, Cardoso L, Coutinho T, Otranto D, Diz-Lopes D. Ocular thelaziosis due to Thelazia callipaeda in a cat from northeastern Portugal. J Feline Med Surg. 2012;14:952–954. doi: 10.1177/1098612X12459645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soares C, Sousa SR, Anastacio S, Matias MG, Marques I, Mascarenhas S, Vieira MJ, de Carvalho LM, Otranto D. Feline thelaziosis caused by Thelazia callipaeda in Portugal. Vet Parasitol. 2013;196:528–531. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Motta B, Nägeli F, Nägeli C, Solari-Basano F, Schiessl B, Deplazes P, Schnyder M. Epidemiology of the eye worm Thelazia callipaeda in cats from southern Switzerland. Vet Parasitol. 2014;203:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Otranto D, Dantas-Torres F, Mallia E, DiGeronimo PM, Brianti E, Testini G, Traversa D, Lia RP. Thelazia callipaeda (Spirurida, Thelaziidae) in wild animals: report of new host species and ecological implications. Vet Parasitol. 2009;166:262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calero-Bernal R, Otranto D, Pérez-Martín JE, Serrano FJ, Reina D. First report of Thelazia callipaeda in wildlife from Spain. J Wildl Dis. 2013;49:458–460. doi: 10.7589/2012-10-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sargo R, Loureiro F, Catarino AL, Valente J, Silva F, Cardoso L, Otranto D, Maia C. First report of Thelazia callipaeda in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from Portugal. J Zoo Wildl Med. 2014;45:458–460. doi: 10.1638/2013-0294R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Otranto D, Dantas-Torres F, Brianti E, Traversa D, Petrić D, Genchi C, Capelli G. Vector-borne helminths of dogs and humans in Europe. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:16. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]