Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the impact of disease activity, the course of the disease, its treatment over time, comorbidities and traditional risk factors on survival.

Methods

Data of the German biologics register RABBIT were used. Cox regression was applied to investigate the impact of time-varying covariates (disease activity as measured by the DAS28, functional capacity, treatment with glucocorticoids, biologic or synthetic disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs)) on mortality after adjustment for age, sex, comorbid conditions and smoking.

Results

During 31 378 patient-years of follow-up, 463 of 8908 patients died (standardised mortality ratio: 1.49 (95% CI 1.36 to 1.63)). Patients with persistent, highly active disease (mean DAS28 > 5.1) had a significantly higher mortality risk (adjusted HR (HRadj)=2.43; (95% CI 1.64 to 3.61)) than patients with persistently low disease activity (mean DAS28 < 3.2). Poor function and treatment with glucocorticoids > 5 mg/d was significantly associated with an increased mortality, independent of disease activity. Significantly lower mortality was observed in patients treated with tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) inhibitors (HRadj=0.64 (95% CI 0.50 to 0.81), rituximab (HRadj=0.57 (95% CI 0.39 to 0.84), or other biologics (HRadj=0.64 (95% CI 0.42 to 0.99), compared to those receiving methotrexate. To account for treatment termination in patients at risk, an HRadj for patients ever exposed to TNFα inhibitors or rituximab was calculated. This resulted in an HRadj of 0.77 (95% CI 0.60 to 0.97).

Conclusions

Patients with long-standing high disease activity are at substantially increased risk of mortality. Effective control of disease activity decreases mortality. TNFα inhibitors and rituximab seem to be superior to conventional DMARDs in reducing this risk.

Keywords: DMARDs (biologic), Methotrexate, Rheumatoid Arthritis, DAS28

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease leading to increased mortality, as shown already in 1953 by Cobb et al1 and subsequently by several longitudinal observational studies.2–4 Early mortality was attributed to poor functional capacity, co-morbid conditions, and markers of RA severity or activity, such as rheumatoid factor or erythrocyte sedimentation rate.5–8

There is evidence from cardiovascular research that persistent systemic inflammation leads to increased mortality.9 10 Additionally, we know that successful control of disease activity by treatment with methotrexate reduces mortality in RA.11 12

During the last decades, treatment strategies in RA have fundamentally changed, favouring early intensive treatment to reach remission as a major therapeutic goal.13 With the approval of tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) inhibitors (infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, certolizumab, and golimumab), rituximab and other biologic agents (abatacept, tocilizumab, and anakinra), seminal advances in treatment options were made, and their efficacy was convincingly shown in randomised clinical trials. So far, six observational studies and one meta-analysis have investigated the impact of TNFα inhibitors on mortality, with conflicting results. Three of them suggested a reduced mortality,14–16 whereas the other four did not.17–20 All but one study compared treatment decisions rather than the direct effects of the drugs. If confounding by indication was adjusted for, only those patient characteristics known at the start of an index treatment were used for adjustment. As shown in one of these studies,19 such an approach is prone to biased estimates. For the analysis of long-term outcomes such as mortality, the impact of changes in exposure and in the risk profiles of the patients over time have to be considered. In our study, we therefore took into account changes in the activity of RA, in functional capacity, fluctuating dosages of glucocorticoids, and changes in the treatment with synthetic or biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) over time. We aimed to estimate the impact of each factor on premature mortality. Our main objectives were (A) to estimate the association between persistent highly active disease and mortality and (B) to evaluate the mortality risk of patients treated with TNFα inhibitors or rituximab compared with patients receiving methotrexate (alone or in combination with other synthetic DMARDs).

Methods

Patients and study design

Data from RABBIT (acronym for: RA observation of biologic therapy), an ongoing prospective cohort study initiated in May 2001 in Germany, were used for the analysis. Patients with RA, according to the American College of Rheumatology 1987 criteria,21 were eligible for enrolment at start of treatment with a biologic or a synthetic DMARD after at least one termination of a treatment with a synthetic DMARD. The enrolment of patients starting infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, anakinra, rituximab, abatacept, tocilizumab, golimumab, or certolizumab began after the approval of the respective biological agent in Germany in 2001, 2003, 2007 or 2009. Participating rheumatologists were asked to enrol consecutive patients with RA who fulfilled the inclusion criteria: age at onset of RA >15 years, start of a new treatment with biologic or synthetic DMARDs after a failure of at least one DMARD treatment, patient scheduled for continuous care. All patients enrolled in RABBIT between May 2001 and June 2011 were included. For the investigation reported here, follow-up ended at 31 December 2011 or at month 108 of follow-up, whichever came first.

The study protocol was approved in 2001 by the ethics committee of the Charité University School of Medicine, Berlin. Each patient participating in the study gave written informed consent before study entry.

Procedures

At baseline and at predefined time points of follow-up (at 3 and 6 months, and thereafter every 6 months), rheumatologists assessed the clinical status, including the disease activity score (DAS28),22 based on four parameters including the erythrocyte sedimentation rate. The rheumatologists further reported treatment details (start and stop dates, dosages) and serious and non-serious adverse events. Patients assessed, among other items, their functional capacity in percent of full function by means of the Hannover Functional Status Questionnaire (Funktionsfragebogen Hannover, FFbH,23 24 see Strangfeld et al25 26 for further details of our study). Vital status was ascertained in patients who had missed two subsequent study visits (n=2568) by contacting first, the rheumatologist; second, the patient or his/her relatives and third, the local registration office. In 58 (2.3%) patients, the vital status could not be ascertained. The procedure systematically covered a period of 24 months after the last visit. All deaths occurring during this period were taken into account. Most of the deaths occurred during the first six (262/463 (56.6%)) or first 12 months (380/463 (82.1%)) after the last study visit.

Main study hypotheses

The following prespecified hypotheses were investigated:

Hypothesis 1: patients with RA with high disease activity over time (mean DAS28 > 5.1) are at increased risk of premature death compared to patients with low disease activity (mean DAS28 < 3.2).

Hypothesis 2: patients treated with TNFα inhibitors during the last 6 months, or rituximab during the last 12 months, do not have an increased mortality compared to patients treated with methotrexate.

Hypothesis 3: patients ever exposed to TNFα inhibitors or rituximab do not have a higher mortality than biologics-naive patients treated with methotrexate.

Statistical analysis

To control for the family-wise α-error, hypotheses 1–3 were tested in a sequential manner according to a closed test principle. The primary analyses were based on multiple Cox regression analysis including prespecified fixed and time-dependent risk factors. Fixed risk factors were recorded at baseline (T0) and included: age, sex, smoking and six groups of comorbid conditions—chronic lung disease, diabetes, coronary heart disease, chronic renal disease, prior malignancy and osteoporosis (as an indicator of a severe course of the disease prior to baseline). Time-dependent risk factors were updated at each time point of follow-up (Tx) and included: mean DAS28 and mean FFbH scores between T0 and Tx, treatment with glucocorticoids during the last 12 months, exposure to synthetic DMARDs, TNFα inhibitors, rituximab, or other biologic DMARDs.

Mean DAS28 scores were categorised into: low disease activity (DAS28 <3.2), moderate disease activity type A (DAS28: 3.2–4.1) and type B (DAS28 4.1–5.1), and high disease activity (DAS28 > 5.1).

Two conservative definitions of exposure to biologics were considered: first, a risk-window approach, considering a patient exposed to a biologic agent if the patient had received the agent during the last six (rituximab: during the last 12) months. Second, an ever-exposed approach was applied to take into account terminations of biologic treatments in patients at increased risk of premature mortality. In this analysis, a patient is considered to be exposed to a biologic after having received the first dose. Since nearly all patients ever exposed to rituximab were also ever exposed to TNFα inhibitors, a distinction between both exposures was not made in this approach. A sustained biologic treatment discontinuation (>6 months, rituximab >12 months) despite active disease (DAS28 >4.1) was considered as an additional risk factor in the primary ever-exposed analysis.

The aim of both approaches was to show non-inferiority of TNFα inhibitors and rituximab compared to treatment with methotrexate (alone or in combination with synthetic DMARDs) regarding fatal outcomes. A non-inferiority margin of 20% was used, and treatment with TNFα inhibitors or rituximab was considered not inferior to treatment with methotrexate (and synthetic DMARDs) whenever the upper bound of the 95% CI of the corresponding adjusted HR was <1.2. After showing non-inferiority, superiority was tested in a closed test procedure. Hypotheses regarding the influence of single anti-TNF agents, or the group of other biologics (abatacept, tocilizumab and anakinra) were investigated in an exploratory manner.

Power considerations were made for hypothesis 1. We expected to observe a more than 50% increase in mortality when comparing patients with DAS28 > 5.1 to those with DAS28 < 3.2 and, therefore, at least 80% power to detect this difference. In this power calculation, the decrease in the power by risk factors which were correlated with DAS28 scores was taken into account. Since there was only a weak correlation between the mean DAS28 scores of the patients and their mean glucocorticoid dosages, which ranged for the different time points between 0.2 and 0.3, it was considered to be possible to distinguish between both effects. Nevertheless, to achieve sufficient power, functional capacity was not used for adjustment when hypothesis 1 was tested, because of a correlation of about 0.5 between mean DAS28 and mean FFbH scores. To test hypotheses 2 and 3, functional capacity was considered as a risk factor of premature mortality and an additional adjustment for this factor was made.

In a secondary analysis, a comparison with the German general population was conducted: patients were classified into four groups according to their DAS28 scores averaged over follow-up. Age-standardised and sex-standardised mortality ratios (SMR) were calculated with the German population rates from 2001 to 2010 as the reference. Life table methods were used to calculate the life expectancy of groups of patients. For each sex and age stratum (5-year bands) the likelihood of surviving was calculated. This estimate was used to calculate the remaining life expectancy taking into account that all patients were living at age 20 years. Comparing these results with the German general population, the life-years lost were calculated. We furthermore estimated 5 years survival rates by means of Cox regression for patients with either a low (mean DAS28 < 3.2) or a high disease activity (mean DAS28 > 5.1) during at least 80% of their available 5-year follow-up time. In sensitivity analyses we excluded patients with a prior malignancy (solid tumour or lymphoma) or heart failure to investigate the influence of a possible channelling bias on the adjusted HRs for biologics. Since we excluded patients with a high mortality risk, the power of this analysis was lower than the power of the primary analysis.

Owing to strict monitoring, treatment data were complete in 99%, and clinical data in 94% of the patients per visit.26 Except in cases for whom we knew that the treatment was discontinued, we assumed that patients who died had continued the treatment until the last months prior to death. Missing smoking information was, however, more frequent (14%). A 10-fold multiple imputation was used to fill in all missing clinical and smoking data; p values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. SAS V.9.3 was used for the analysis.

Results

Between 1 May 2001 and 30 June 2011, a cohort of 8908 patients with RA, with a mean age of 55.8 (SD 12.4) years at baseline was enrolled. The mean follow-up was 3.5 years (SD: 2.6; IQR: 1.2–5.4). Follow-up of five, seven, or 8 years was available for 2992, 1228 and 629 patients, respectively. Patients receiving anti-TNF agents, rituximab, or other biologic drugs, had a significantly more active disease, and they were more limited in activities of daily living than patients treated with synthetic DMARDs only (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by treatment group at inclusion

| MTX | sDMARDs no MTX | TNFα inhibitors | Rituximab | Other biologics | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 2060 | 928 | 4649 | 703 | 568 | 8908 |

| Follow-up (months)* | 43.9 (32.7) | 39.4 (31.7) | 46.5 (32.3) | 28.0 (14.6) | 25.4 (23.1) | 42.4 (31.6) |

| Female | 1565 (76.0) | 744 (80.2) | 3584 (77.1) | 552 (78.5) | 438 (77.1) | 6883 (77.3) |

| Age | 56.4 (12.0) | 58.5 (12.4) | 54.5 (12.4) | 58.5 (12.0) | 56.4 (12.9) | 55.8 (12.4) |

| Disease duration | 7.2 (7.7) | 8.8 (9.3) | 11.2 (9.3) | 13.6 (10.2) | 12.9 (9.0) | 10.3 (9.2) |

| Rheumatoid factor positive | 1361 (66.1) | 591 (63.7) | 3614 (78.0) | 578 (82.3) | 416 (73.9) | 6560 (73.8) |

| DAS28 | 4.9 (1.3) | 4.8 (1.3) | 5.6 (1.3) | 5.5 (1.3) | 5.6 (1.3) | 5.3 (1.3) |

| Percent of full function (FFbH) | 69.2 (21.6) | 67.7 (22.0) | 59.2 (23.1) | 53.8 (23.6) | 58.1 (23.9) | 61.9 (23.3) |

| Glucocorticoids | 1260 (61.1) | 516 (55.6) | 3456 (73.3) | 523 (74.4) | 400 (70.4) | 6155 (69.1) |

| Prednisone dose (mg/d) | 4.2 (5.4) | 3.6 (4.4) | 6.4 (7.0) | 6.3 (5.9) | 6.0 (6.0) | 5.6 (6.3) |

| Diabetes | 175 (8.5) | 101 (10.9) | 418 (9.0) | 76 (10.8) | 58 (10.2) | 828 (9.3) |

| Coronary heart disease | 114 (5.5) | 70 (7.5) | 324 (7.0) | 84 (12.0) | 51 (9.0) | 643 (7.2) |

| Among them: heart failure | 20 (1.0) | 11 (1.2) | 110 (2.4) | 41 (5.8) | 24 (4.2) | 206 (2.3) |

| Chronic lung disease | 111 (5.4) | 77 (8.3) | 349 (7.5) | 65 (9.3) | 36 (6.3) | 638 (7.2) |

| Chronic renal disease | 23 (1.1) | 26 (2.8) | 188 (4.0) | 45 (6.4) | 30 (5.3) | 312 (3.5) |

| Prior malignancy | 69 (3.4) | 32 (3.5) | 96 (2.1) | 82 (11.7) | 28 (4.9) | 307 (3.4) |

| Osteoporosis | 291 (14.1) | 157 (16.9) | 986 (21.2) | 194 (27.6) | 138 (24.3) | 1766 (19.8) |

| Smoker | 501 (24.3) | 178 (19.2) | 1077 (23.2) | 161 (23.0) | 136 (24.0) | 2053 (23.1) |

Values are means (SDs) or numbers (%) as appropriate. Methotrexate (MTX) group: patients treated with MTX alone or in combination with other synthetic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (sDMARD), sDMARD no MTX group: treatment with sDMARDs without MTX.

*Follow-up of patients per treatment group at inclusion.

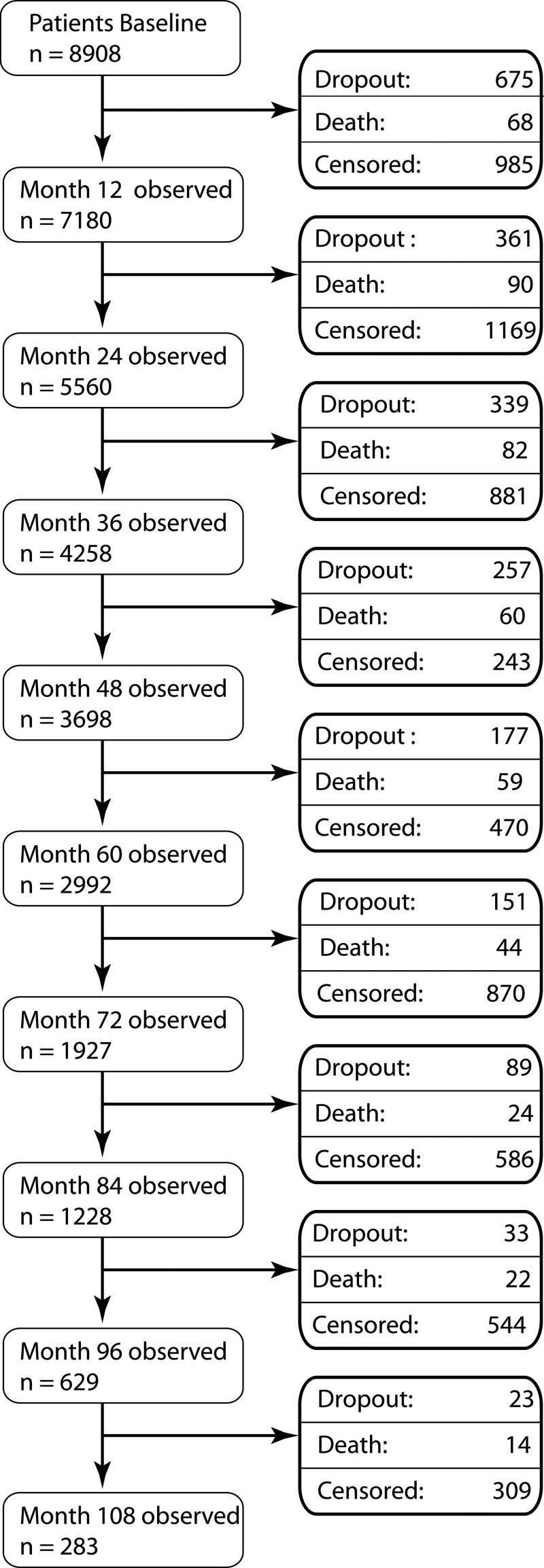

Within an observation period of 31 378 patient-years, a total of 463 patients died (figure 1). Patients who dropped out of the observation had, on average, a 0.3 units higher DAS28 score (4.2) at their last study visit than patients who completed the corresponding visit. This difference was even higher (0.6 units) in patients who died (mean last DAS28: 4.4). Causes of death are shown in the online supplementary table ST1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patients enrolled. Censored: patients who were in this study on 31 December 2011 but did not complete a follow-up period of 9 years since they were enrolled after January 2003. The follow-up time of these patients was censored at the last regular study visit. Dropouts: patients lost to follow-up.

Significantly elevated standardised mortality ratios were observed in men and women (table 2). The increase was associated with patients having highly active disease (DAS28 > 5.1), on average, over time, whereas, no increase was found in patients with low disease activity (DAS28 < 3.2). In terms of remaining life expectancy at age 20 years, women RABBIT patients generally expected 59.9 further life years (men 55.3), which is about 2 years less than the agematched and sexmatched population (table 2). In the case of highly active disease (DAS28 > 5.1), women patients lost 10.3 years (men 10.7) compared with the population (table 2).

Table 2.

Standardised mortality ratios (SMR) and life-years lost, in comparison with the German general population by groups of patients with different mean disease activity (DAS28) scores at follow-up

| Women | Men | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAS28 | Deaths | SMR (95% CI) | Lost life years (95% CI) | Deaths | SMR (95% CI) | Lost life years (95% CI) |

| <3.2 | 29 | 0.86 (0.58 to1.24) | −1.5 (−3.0 to 0.0) | 13 | 0.54 (0.29 to 0.92) | −2.4 (−6.1 to1.3) |

| 3.2–4.1 | 60 | 0.94 (0.72 to1.22) | 0.0 (−1.4 to 1.4) | 39 | 1.11 (0.79 to 1.52) | 0.1 (−2.1 to 2.3) |

| >4.1–5.1 | 88 | 1.35 (1.09 to 1.67) | 3.0 (1.1 to 4.9) | 42 | 1.34 (0.96 to 1.81) | 0.5 (−1.3 to 2.1) |

| >5.1 | 132 | 3.33 (2.79 to 3.95) | 10.3 (8.9 to 11.6) | 60 | 3.33 (2.54 to 4.30) | 10.7 (8.9 to 12.6) |

| Total | 309 | 1.53 (1.37 to 1.71) | 2.7 (2.0 to 3.4) | 154 | 1.41 (1.20 to 1.65) | 1.9 (0.8 to 3.0) |

The results found in comparison to the German population were confirmed by multiple Cox regression analysis. Patients who, on average, remained in a state of highly active disease (DAS28 > 5.1) over time had a more than twofold mortality risk (HR: 2.43; 95% CI 1.64 to 3.61, table 3) compared to those with low disease activity (DAS28 < 3.2).

Table 3.

Adjusted HRs of death by categories of mean disease activity of the patients at follow-up

| PYRS | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAS28<3.2 | 6730 | Referent | |

| DAS28 3.2–4.1 | 8875 | 1.29 (0.85 to 1.93) | 0.21 |

| DAS28>4.1–5.1 | 8773 | 1.42 (0.96 to 2.10) | 0.073 |

| DAS28>5.1 | 6999 | 2.43 (1.64 to 3.61) | 0.0001 |

The risk window approach was used to calculate the adjusted HRs. Adjustments were made for age, sex, smoking, comorbid conditions (chronic lung disease, diabetes, coronary heart disease, chronic renal disease, prior malignancy and osteoporosis) and as time-dependent risk factors treatment with glucocorticoids, treatment with methotrexate, other synthetic disease modifying antirheumatic drugs, TNFα inhibitors, rituximab, or other biologics. Updated FFbH scores were not included in the risk set. (PYRS: patient-years).

This association was significant after control for treatment with glucocorticoids, and remained significant after additional adjustment for functional capacity, a disease outcome which is correlated with DAS28 (table 4 column 4–6). Patients treated with higher dosages of glucocorticoids had a significantly higher mortality, whereas, those exposed to TNFα inhibitors (during the last 6 months), rituximab (during the last 12 months) or other biologics (last 6 months) had a significantly lower risk of dying early (table 4 column 4–6).

Table 4.

Adjusted HRs ; Adjustments were made for all parameters shown in the table

| Unadjusted HR | Adjusted HR: 6 (rituximab 12) months risk window approach | Adjusted HR: Ever exposed approach | Deaths | PYRS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | p Value | HR | 95% CI | p Value | |||

| At baseline | ||||||||||

| Male | 1.85 | 1.53 to 2.25 | 1.75 | 1.40 to 2.18 | <0.0001 | 1.72 | 1.38 to 2.14 | <0.0001 | 154 | 6718 |

| Age per 5 years | 1.66 | 1.57 to 1.75 | 1.49 | 1.40 to 1.59 | <0.0001 | 1.50 | 1.41 to 1.60 | <0.0001 | 31 378 | |

| Diabetes | 3.43 | 2.77 to 4.26 | 1.84 | 1.46 to 2.33 | <0.0001 | 1.85 | 1.46 to 2.33 | <0.0001 | 108 | 2633 |

| Chronic lung disease | 3.31 | 2.63 to 4.17 | 1.68 | 1.31 to 2.17 | 0.0003 | 1.71 | 1.32 to 2.20 | 0.0002 | 89 | 2125 |

| Chronic renal disease | 4.90 | 3.71 to 6.47 | 1.94 | 1.43 to 2.63 | 0.0001 | 1.92 | 1.41 to 2.61 | 0.0002 | 57 | 926 |

| Prior malignancy | 3.15 | 2.27 to 4.37 | 1.26 | 0.88 to 1.80 | 0.20 | 1.27 | 0.89 to 1.81 | 0.18 | 39 | 927 |

| Osteoporosis | 2.86 | 2.38 to 3.43 | 1.43 | 1.16 to 1.76 | 0.0015 | 1.41 | 1.15 to 1.73 | 0.0020 | 199 | 6718 |

| Coronary heart disease | 4.94 | 4.00 to 6.10 | 1.43 | 1.12 to 1.83 | 0.006 | 1.46 | 1.14 to 1.86 | 0.0036 | 115 | 2017 |

| Smoker | 0.82 | 0.62 to 1.07 | 1.37 | 1.02 to 1.85 | 0.038 | 1.36 | 1.01 to 1.83 | 0.042 | 86 | 6936 |

| At follow-up | ||||||||||

| DAS28* <3.2 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | 42 | 6730 | |||||

| DAS28* 3.2–4.1 | 1.81 | 1.21 to 2.71 | 1.15 | 0.76 to 1.74 | 0.49 | 1.11 | 0.74 to 1.68 | 0.59 | 99 | 8875 |

| DAS28* >4.1 to 5.1 | 2.29 | 1.57 to 3.33 | 1.17 | 0.78 to 1.75 | 0.43 | 1.08 | 0.72 to 1.61 | 0.70 | 130 | 8773 |

| DAS28>5.1 | 4.86 | 3.35 to 7.04 | 1.75 | 1.14 to 2.68 | 0.013 | 1.54 | 1.00 to 2.38 | 0.0499 | 192 | 6999 |

| Prednisone most recent 12 months: 0 mg/d | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | 88 | 9036 | |||||

| 1–5 mg/d | 1.33 | 1.00 to 1.76 | 1.05 | 0.80 to 1.38 | 0.71 | 1.04 | 0.79 to 1.37 | 0.77 | 177 | 13 615 |

| >5–10 mg/d | 2.22 | 1.65 to 2.98 | 1.46 | 1.09 to 1.95 | 0.013 | 1.41 | 1.06 to 1.89 | 0.021 | 140 | 7086 |

| >10–15 mg/d | 3.95 | 2.61 to 5.98 | 2.00 | 1.29 to 3.11 | 0.0033 | 2.01 | 1.30 to 3.11 | 0.0030 | 37 | 1170 |

| >15 mg/d | 6.68 | 4.06 to 11.0 | 3.59 | 2.11 to 6.13 | <0.0001 | 3.43 | 2.01 to 5.86 | <0.0001 | 21 | 448 |

| FFbH* in % of full function per 10% improvement | 0.76 | 0.73 to 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.84 to 0.93 | <0.0001 | 0.89 | 0.85 to 0.93 | <0.0001 | 31 378 | |

| Methotrexate | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | 96†/78‡ | 7012†/6469‡ | |||||

| Other synth. DMARDs | 2.53 | 1.95 to 3.28 | 1.14 | 0.86 to 1.51 | 0.36 | 0.98 | 0.60 to 1.59 | 0.92 | 126†/31‡ | 3513†/1581‡ |

| TNFα inhibitors | 0.77 | 0.61 to 0.98 | 0.64 | 0.50 to 0.81 | 0.0007 | NA | 182† | 16 843† | ||

| Rituximab | 1.01 | 0.70 to 1.46 | 0.57 | 0.39 to 0.84 | 0.0062 | NA | 36† | 2599† | ||

| TNFα inhibitors or rituximab | NA | NA | 0.77 | 0.60 to 0.97 | 0.0312 | 330‡ | 22 370‡ | |||

| Other biologics | 1.02 | 0.68 to 1.52 | 0.64 | 0.42 to 0.99 | 0.043 | 0.91 | 0.66 to 1.25 | 0.54 | 25†/51‡ | 1654†/2806‡ |

| DAS28>4.1 for > 6 (12) months after discon- tinuation of a biologic without start of a new one | NA | NA | 2.08 | 1.59 to 2.72 | <0.0001 | 86‡ | 1812‡ | |||

*Average of single DAS28 or FFbH scores between baseline and last time point prior to the event, FFbH: Function questionnaire (see Methods) (range 0–100%).

†Risk window approach.

‡Ever exposed approach.

DMARD, disease modifying antirheumatic drugs; PYRS: patient years; Ref., referent.

Even using a conservative ‘ever exposed’ approach, we found a significantly lower mortality in patients ever exposed to TNFα inhibitors or rituximab, compared to methotrexate therapy (HR=0.77; 95% CI 0.60 to 0.97), whereas, sustained treatment discontinuation (>6 months see Methods) despite active disease was associated with a significantly higher risk of dying (HR=2.08; 95% CI 1.59 to 2.72). When attributing the risk resulting from sustained treatment discontinuation to the biologic the patient had received before, we found in this secondary analysis no increase in the mortality risk in patients ever exposed to TNFα inhibitors or rituximab (HR=0.85; 95% CI 0.67 to 1.08).

Similar results were found in the sensitivity analyses. When we excluded patients with prior malignancies (solid tumours or lymphoma) we could still confirm hypotheses 2 and 3, that treatment with TNFα inhibitors or rituximab was not inferior to treatment with methotrexate (data not shown). A similar result was found after additional exclusion of patients with prior heart failure.

Comparing the individual treatments, the HRs for individual biologic agents with methotrexate as reference group are shown in the online supplementary table ST2. In the online supplementary table ST3 HRs for TNFα inhibitors are given with etanercept as reference. No significant differences between the anti-TNF agents were seen in the ‘6-months risk window’ or the ‘ever exposed’ approaches.

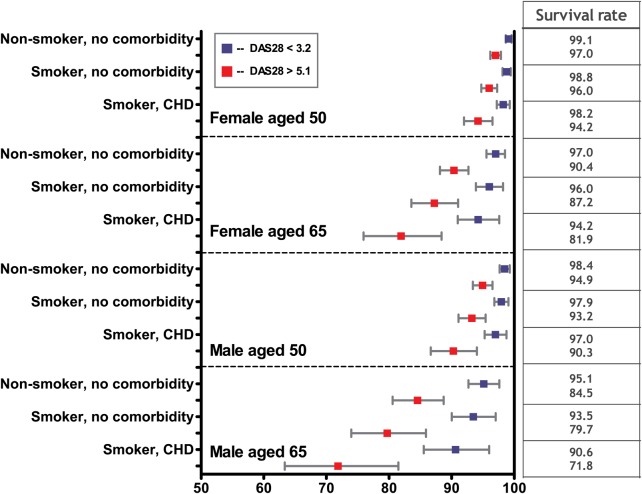

To put the relative risks into context, we furthermore estimated 5 years survival rates according to the overall disease activity status of the patients. Figure 2 shows the results for women and men at ages 50 and 65 years. The difference in survival between patients with low and high disease activity were significant and ranged from 3% to 23%, depending on age, sex, smoking and comorbidity status.

Figure 2.

Five-year survival rates (in %) for patients with highly active disease (DAS28 scores >5.1 at ≥80% of the observation time (18% of patients) and low disease activity (DAS28 scores <3.2 for ≥80% of the observation time (9% of patients) CHD: coronary heart disease.

Discussion

We found evidence for a significant association between highly active RA and mortality. Patients with a persistent, highly active disease had a significantly higher mortality than those with a mean DAS28 < 3.2. Patients with low functional capacity, with diabetes, chronic lung or chronic renal diseases, cardiac disorders as well as those treated with higher dosages of glucocorticoids, were at a further increased risk. Treatment with more than 5 mg/d glucocorticoids was significantly associated with an increased mortality risk in a dose-dependent manner. Patients treated with TNFα inhibitors or rituximab had a significantly reduced premature mortality compared to those treated with methotrexate alone or in combination with other synthetic DMARDs. No significant differences between the individual TNFα inhibitors were seen, which is in agreement with a recent study from the Swedish biologics register.27

The strength and novelty of our study is that it took into account changes in patient characteristics (disease activity, functional capacity) and treatment details (eg, fluctuating glucocorticoid dosages) at all time points during long-term follow-up, in order to achieve valid estimates of the risk of mortality conveyed by biologic agents in comparison with conventional DMARD therapy. This approach is more robust than an approach adjusting only for patient's baseline characteristics, for example, by propensity score methods.19

To our knowledge, our study is the first to differentiate the impact of inflammation on all-cause mortality from the impact of glucocorticoids. Since the mean disease activity of individual patients and the mean glucocorticoid dose they received for the treatment of RA were only weakly correlated, we were able to distinguish between both risk factors. The clinical relevance of the findings is expressed by the number of lost life years and by 5-year survival rates, which substantially differ between patients in low and high disease activity. The findings are in concordance with reports on the impact of inflammation on premature death from cardiovascular diseases,9 chronic lung diseases28 and lymphoma.29

Significant associations between mortality and glucocorticoid use (as time-varying yes/no parameter) were described by Mikuls et al5 and Jacobsson et al.15 A dose-related association is supported by findings of an increased cardiovascular as well as all-cause mortality associated with the use of glucocorticoids.30–32 When analysing the incidence of serious infections in our biologics register, we recently found a significant association between the glucocorticoid dose and the magnitude of the risk.26 One might object that glucocorticoid use is an indicator for severe disease, and that the association between increased mortality and higher dosages of glucocorticoids found in our data and in those of others only relates to a persistently high disease activity. This view is, however, not supported by our data since we already adjusted for disease activity, functional capacity and comorbidities. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out unmeasured confounding, and we therefore invite other researchers to re-examine our findings.

We observed a reduced mortality in patients treated with TNFα inhibitors or rituximab. Since we compared patients by taking their disease activity on treatment into account, a potential additional benefit of biologics resulting from their higher efficacy was not considered. However, this strengthens rather than weakens our findings.

Our study has some limitations. It was underpowered to show significant effects for infliximab, etanercept, certolizumab, golimumab, abatacept, tocilizumab, or anakinra separately. We were so far only able to show the effects for the group of TNFα inhibitors and for rituximab. Further, generalisability of the results to the German population is limited since our register includes patients on the upper end of the disease severity spectrum. Patients with RA who do well on methotrexate monotherapy are not included in the control group. We might, therefore, have underestimated beneficial effects of methotrexate. Finally, due to the observational nature of the study, and due to a rather long list of risk factors and confounders, residual confounding with an impact on the results cannot be ruled out.

Conclusion

Taking the course of disease into account, we observed an increased mortality in patients with persistent, highly active disease, and in patients treated with higher dosages of glucocorticoids. We further found that TNFα inhibitors and rituximab, and possibly other biologics, reduced the mortality compared to treatment with methotrexate (alone or in combination with other synthetic DMARDs).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the invaluable contributions of all participating consultant rheumatologists. In particular, we would like to thank those who enrolled 25 patients or more: Jörg Kaufmann, MD, Ludwigsfelde; Thilo Klopsch, MD, Neubrandenburg; Andreas Krause, MD, Immanuel Hospital Berlin; Constanze Richter, MD, Stuttgart Bad-Cannstatt; Karin Babinsky, MD, and Anke Liebhaber, MD, Halle; Hans Joachim Berghausen, MD, Duisburg; Arnold Bussmann, MD, Geilenkirchen; Hans Peter Tony, MD, Medizinische Poliklinik der Universität Würzburg; Katja Richter, MD, Universitätsklinikum Carl Gustav Carus Dresden; Andreas Kapelle, MD, Hoyaswerda; Karin Rockwitz, MD, Goslar; Rainer Dockhorn, MD, Weener; Siegfried Wassenberg, MD, Ratingen; Brigitte Krummel-Lorenz, MD, Frankfurt am Main; Anett Gräßler, MD, Pirna; Elke Wilden, MD, Köln; Michael Hammer, MD, St. Josef-Stift Sendenhorst; Edmund Edelmann, MD, Bad Aibling; Winfried Demary, MD, Hildesheim; Martin Aringer, MD, Dresden; Sven Remstedt, MD, Berlin; Christina Eisterhues, MD, Braunschweig; Wolfgang Ochs, MD, Bayreuth; Thomas Karger, MD, Eduardus-Krankenhaus Köln-Deutz; Michael Bäuerle, MD, Nürnberg; Sabine Balzer, MD, Bautzen; Anna-Elisabeth Thiele, MD, Berlin; Sebastian Lebender, MD, Hamburg; Elisabeth Ständer, MD, Schwerin; Helge Körber, MD, Elmshorn; Herbert Kellner, MD, München; Silke Zinke, MD, Berlin; Angela Gause, MD, Elmshorn; Lothar Meier, MD, Hofheim; Karl Alliger, MD, Zwiesel; Martin Bohl-Bühler, Potsdam; Carsten Stille, MD, Hannover; Susanna Späthling-Mestekemper, MD, and Thomas Dexel, MD, München; Ulrich von Hinüber, MD, Hildesheim; Harald Tremel, MD, Hamburg; Stefan Schewe, MD, Medizinische Poliklinik der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München; Helmut Sörensen, MD, Krankenhaus Waldfriede Berlin; Florian Schuch, MD, Erlangen; Klaus Krüger, MD, München; Andreas Teipel, MD, Leverkusen; Kirsten Karberg, MD, Berlin; Gisela Maerker-Alzer, MD, and Dorothea Pick, MD, Holzweiler; Volker Petersen, MD, Hamburg; Kerstin Weiss, MD, Lichtenstein; Sylvia Berger, MD, Naunhof; Mathias Grünke, MD, München; Peter Herzer, MD, München; Matthias Schneider, MD, Düsseldorf; Frank Moosig, MD, Bad Bramstedt; Cornelia Kühne, MD, Haldensleben; Jürgen Rech, MD, Erlangen; Dietmar Krause, MD, Gladbeck Werner Liman, MD, Ev. Krankenhaus Hagen-Haspe; Kurt Gräfenstein, MD, Johanniter-Krankenhaus im Fläming, Treuenbrietzen; Jochen Walter, MD, Rendsburg; Werner A Biewer, MD, Saarbrücken; Roland Haux, MD, Berlin; Rieke Alten, MD, Berlin; Wolfgang Gross, MD, Lübeck; Michael Zänker, MD, Evangelisches Freikirchliches Krankenhaus Eberswalde; Gerhard Fliedner, MD, Osnabrück; Thomas Grebe, MD, Ev. Krankenhaus Kredenbach; Karin Leumann, MD, Riesa; Jörg-Andres Rump, MD, Freiburg; Joachim Gutfleisch, MD, Biberbach; Michael Schwarz-Eywill, MD, Evangelisches Krankenhaus Oldenburg; Kathrin Fischer, MD, Greifswald; Monika Antons, MD, Köln Johannes Häntsch, MD Darmstadt. We also acknowledge the significant contributions of Matthias Schneider, MD, University of Düsseldorf, and Peter Herzer, MD, Munich for their service as members of the advisory board. Their work on the RABBIT advisory board is honorary and without financial compensation. We gratefully recognise the substantial contributions of Ulrike Kamenz, Susanna Zernicke, Bettina Marsmann, Adrian Richter, Steffen Meixner, all employees of the German Rheumatism Research Centre, Berlin, in the study monitoring and support of the data analyses.

Footnotes

Contributors: JL DP, AZ, and AS had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. Study concept and design: JL, AZ, AS. Acquisition of the data: JK, BM, G-RB, DP. Analysis and interpretation of the data: JL, DP, AZ, AS. Drafting the manuscript: JL, AZ, AS. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: JL, JK, BM, G-RB, DP, AZ, AS. Obtained funding and Study supervision: JL, AZ, AS.

Funding: Supported by a joint, unconditional grant from Abbott/AbbVie, Amgen/Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck-Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB.

Competing interests: JL: Lecture honoraria: Abbott.

BM: Honoraria for consultancy and lectures: Abbott, BMS, Merck-Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Roche, UCB. G-RB: Honoraria for consultancy and lectures: Abbott, BMS, Merck-Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Roche, UCB. AZ: Lecture honoraria: BMS, Merck-Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Roche, UCB. AS: Lecutre honoraria: BMS, Merck-Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethics committee of the Charite University School of Medicine Berlin.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Cobb S, Anderson F, Bauer W. Length of life and cause of death in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 1953;249:553–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe F, Mitchell DM, Sibley JT, et al. The mortality of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37:481–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjornadal L, Baecklund E, Yin L, et al. Decreasing mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from a large population based cohort in Sweden, 1964–95. J Rheumatol 2002;29:906–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez A, Maradit KH, Crowson CS, et al. The widening mortality gap between rheumatoid arthritis patients and the general population. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:3583–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mikuls TR, Fay BT, Michaud K, et al. Associations of disease activity and treatments with mortality in men with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the VARA registry. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:101–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.del Rincon ID, Williams K, Stern MP, et al. High incidence of cardiovascular events in a rheumatoid arthritis cohort not explained by traditional cardiac risk factors. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:2737–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez-Gay MA, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Lopez-Diaz MJ, et al. HLA-DRB1 and persistent chronic inflammation contribute to cardiovascular events and cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:125–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolfe F, Michaud K, Gefeller O, et al. Predicting mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:1530–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sattar N, McCarey DW, Capell H, et al. Explaining how “high-grade” systemic inflammation accelerates vascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation 2003;108:2957–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sattar N, Murray HM, McConnachie A, et al. C-reactive protein and prediction of coronary heart disease and global vascular events in the Prospective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER). Circulation 2007;115:981–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi HK, Hernan MA, Seeger JD, et al. Methotrexate and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study. Lancet 2002;359:1173–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krause D, Schleusser B, Herborn G, et al. Response to methotrexate treatment is associated with reduced mortality in patients with severe rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:631–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carmona L, Descalzo MA, Perez-Pampin E, et al. All-cause and cause-specific mortality in rheumatoid arthritis are not greater than expected when treated with tumour necrosis factor antagonists. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:880–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobsson LT, Turesson C, Nilsson JA, et al. Treatment with TNF blockers and mortality risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:670–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burmester GR, Panaccione R, Gordon KB, et al. Adalimumab: long-term safety in 23 458 patients from global clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and Crohn's disease. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:517–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lunt M, Watson KD, Dixon WG, et al. No evidence of association between anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:3145–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Aly Z, Pan H, Zeringue A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade, cardiovascular outcomes, and survival in rheumatoid arthritis. Transl Res 2011;157:10–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lunt M, Solomon D, Rothman K, et al. Different methods of balancing covariates leading to different effect estimates in the presence of effect modification. Am J Epidemiol 2009;169:909–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leombruno JP, Einarson TR, Keystone EC. The safety of anti-tumour necrosis factor treatments in rheumatoid arthritis: meta and exposure-adjusted pooled analyses of serious adverse events. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1136–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988;31:315–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prevoo ML, van't Hof MA, Kuper HH, et al. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:44–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lautenschlaeger J, Mau W, Kohlmann T, et al. [Comparative evaluation of a German version of the Health Assessment Questionnaire and the Hannover Functional Capacity Questionnaire]. Z Rheumatol 1997;56:144–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Westhoff G, Listing J, Zink A. Loss of physical independence in rheumatoid arthritis: interview data from a representative sample of patients treated in tertiary rheumatologic care. Arthr Care Res 2000;13:11–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strangfeld A, Listing J, Herzer P, et al. Risk of herpes zoster in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with anti-TNF-alpha agents. JAMA 2009; 301:737–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strangfeld A, Eveslage M, Schneider M, et al. Treatment benefit or survival of the fittest: what drives the time-dependent decrease in serious infection rates under TNF inhibition and what does this imply for the individual patient? Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1914–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simard JF, Neovius M, Askling J. Mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with TNF inhibitors: drug-specific comparisons in the swedish biologics register. Arthritis Rheum 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sin DD, Anthonisen NR, Soriano JB, et al. Mortality in COPD: role of comorbidities. Eur Respir J 2006;28:1245–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baecklund E, Iliadou A, Askling J, et al. Association of chronic inflammation, not its treatment, with increased lymphoma risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:692–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis JM, III, Maradit KH, Crowson CS, et al. Glucocorticoids and cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:820–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei L, MacDonald TM, Walker BR. Taking glucocorticoids by prescription is associated with subsequent cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:764–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sihvonen S, Korpela M, Mustonen J, et al. Mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with low-dose oral glucocorticoids. A population-based cohort study. J Rheumatol 2006;33:1740–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.