Abstract

Objective

To determine which antenatal and early-life factors were associated with infant postnatal growth in a resource-poor setting in Vietnam.

Study design

Prospective longitudinal study following infants (n=1046) born to women who had previously participated in a cluster randomised trial of micronutrient supplementation (ANZCTR:12610000944033), Ha Nam province, Vietnam. Antenatal and early infant factors were assessed for association with the primary outcome of infant length-for-age z scores at 6 months of age using multivariable linear regression and structural equation modelling.

Results

Mean length-for-age z score was −0.58 (SD 0.94) and stunting prevalence was 6.4%. Using structural equation modelling, we highlighted the role of infant birth weight as a predictor of infant growth in the first 6 months of life and demonstrated that maternal body mass index (estimated coefficient of 45.6 g/kg/m2; 95% CI 34.2 to 57.1), weight gain during pregnancy (21.4 g/kg; 95% CI 12.6 to 30.1) and maternal ferritin concentration at 32 weeks' gestation (−41.5 g per twofold increase in ferritin; 95% CI −78 to −5.0) were indirectly associated with infant length-for-age z scores at 6 months of age via birth weight. A direct association between 25-(OH) vitamin D concentration in late pregnancy and infant length-for-age z scores (estimated coefficient of −0.06 per 20 nmol/L; 95% CI −0.11 to −0.01) was observed.

Conclusions

Maternal nutritional status is an important predictor of early infant growth. Elevated antenatal ferritin levels were associated with suboptimal infant growth in this setting, suggesting caution with iron supplementation in populations with low rates of iron deficiency.

Keywords: Growth, Stunting, Infant, Antenatal iron

What is already known on this topic.

Adverse growth outcomes within the first two years of life may result in significant consequences in later life.

Prevalence of stunting in Asia is high, and the key maternal and early-life factors and their interactions leading to impaired infant growth remain unclear.

What this study adds.

Maternal nutritional status plays an important role in predicting infant growth at 6 months of age.

Elevated antenatal iron stores may be deleterious to infant growth in this setting.

Caution with antenatal iron supplementation should be taken in populations with low rates of iron deficiency.

Introduction

A child's growth and development are largely determined by conditions experienced in utero and during their first two years of life. Chronic undernutrition during this period may lead to irreversible adverse outcomes in later life, including impaired growth, reduced cognitive development, impaired immune function and increased risk of chronic diseases in later life, resulting in long-term consequences for health and productivity in adult life.1 2

Chronic undernutrition is a major global public health issue, and stunting (the best indicator of chronic undernutrition) has been shown to affect 165 million children throughout the world. Impaired growth is rarely caused by a single determinant, rather it is the cumulative result of many different biological, cultural and socio-economic influences occurring during the antenatal and early infancy period. Patterns of growth faltering show that length-for-age decreases dramatically from birth until 24 months of age,3 and fetal growth restriction is an important contributor to childhood stunting.4

A recent review identified 10 key interventions for improving maternal and child undernutrition, including antenatal folic acid or multiple micronutrient (MMN) supplementation, and exclusive breast and complementary feeding promotion. However, modelling has shown that at 90% coverage, these evidence-based nutrition interventions would only reduce stunting by 20% in children under 5 years of age at a cost of Int$9.6 billion per year.5 Thus, further clarification of critical maternal and early-life factors that influence infant growth and exploration of how these factors interact is urgently required.

In Vietnam, stunting affects between 15% and 30% of children, with the highest incidence in children residing in rural areas and from ethnic minority groups.6 7 Potential factors contributing to the high rates of stunting in Vietnam may include poor maternal health and nutrition, inadequate infant nutrition in early life, as well as other socio-economic and cultural influences.7

Our overall objective was to determine which factors occurring during the antenatal period and first six months of life were associated with infant growth (length-for-age z scores) at 6 months of age, and to clarify whether associations were direct, or indirectly mediated via infant birth weight. Using this information, we aimed to develop a comprehensive explanatory model for factors impacting growth in infants residing in rural Vietnam.

Methods

Study design, setting and participants

This prospective cohort study was conducted in Ha Nam province in northern Vietnam between September 2010 and January 2012. Ha Nam has a population of approximately 820 100 people, with most residents still working in subsistence agriculture. The original study protocol was approved by the Melbourne Health and Ha Nam Provincial Human Research Ethics Committees. All women and infants enrolled in the original cluster randomised trial (ACTNR 12610000944033) were eligible for enrolment in the study if length-for-age z scores were available at 6 months of age.

In the original trial, women received either (1) one tablet of iron-folic acid (IFA) taken daily (60 mg elemental iron/0.4 mg folic acid per tablet, seven tablets per week) or (2) one capsule of IFA taken twice a week (60 mg elemental iron/1.5 mg folic acid per capsule; two capsules per week) or (3) one capsule of MMNs taken twice a week (60 mg elemental iron/1.5 mg folic acid per capsule; two capsules per week, as well as a variation of the dose of the micronutrients in the United Nations International Multiple Micronutrient Preparation supplement).8 Maternal information was collected at enrolment (mean gestational age 12.2 weeks) and 32 weeks gestation, and infant anthropometric measurements were performed at birth, 6 weeks and 6 months of age. Detailed information on the methodology used, including a table describing the composition of the supplements, has been previously published.9

The wealth index was used to measure the socio-economic status of the household and was constructed from three component indices: housing quality (four items, response 0 or 1), consumer durables (nine items, response 0 or 1) and services (four items, response 0 or 1). A simple average of these three components was calculated to produce a value between 0 and 1 (scale from poorest to better-off).10

Infant crown-heel length was measured using a portable Shorr Board (Shorr productions, Olney, Maryland, USA). Infant length-for-age z scores were calculated using WHO Anthro (V.3.2.2, January 2011).11 Stunting was defined as length-for-age z scores <2 SDs below WHO Child Growth Standards.12

Statistical methods

Data were analysed using Stata, V.12 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). Categorical data are presented as percentages with frequency, and continuous data are presented as mean and SD. Data found to be skewed were presented as the median with IQRs (25th –75th centile) and log transformed for the regression analyses. The assumption of a linear association between continuous exposure measures and infant height for age z scores was tested by comparing regression models with categorical (quartile groupings) and pseudo-continuous variables by likelihood ratio tests. Variables that had no evidence for non-linearity of associations were used as continuous variables. In order to enhance clinical interpretability, maternal ferritin concentration was also categorised into four quartiles (lowest to highest). We tested for exposure–outcome associations that may have been modified by the trial intervention arm (exposures: ferritin, folate, B12, vitamin D and iodine concentration) using interaction terms and the likelihood ratio test, and found no evidence of interaction.

The rationale for using a structural equation model was based on the hypothesis that maternal and early infant factors have a complex and inter-related influence on early infant growth. We initially constructed a hypothesised causal diagram for how these factors and infant length-for-age z scores may be connected. Following this, univariable and multivariable linear regression was performed to examine the association between maternal (early and late) and early infant factors that predicted infant birth weight and length-for-age z scores at 6 months of age. Separate multivariable linear regression models for maternal and early infant factors were developed using backward elimination stepwise regression as a way of selecting a subset of variables that were statistically significantly associated with infant birth weight and length-for-age z scores. The models obtained this way were then improved by including/excluding variables with borderline p values, clinically important confounding factors identified a priori from the literature and those that had statistically significant associations with length-for-age z scores at 6 months of age in the univariable analysis. Proceeding this way, the optimal models were selected with the aid of likelihood ratio tests and adjusted R2 values.13

Using the results of the univariable and multivariable regression analysis, the structural equation model was built and iteratively tested. The fit of the model was tested using the χ2 test comparing the fitted model with a saturated model, comparative fit index (CFI) comparing the fitted model with a baseline model, which assumes that there is no relationship among the variables, and root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) that penalises the model for excessive complexity.13 14 A good model should have an insignificant p value for the χ2 test (≥0.05), CFI close to one (≥0.95) and low RMSEA (≤0.05).13 14

Results

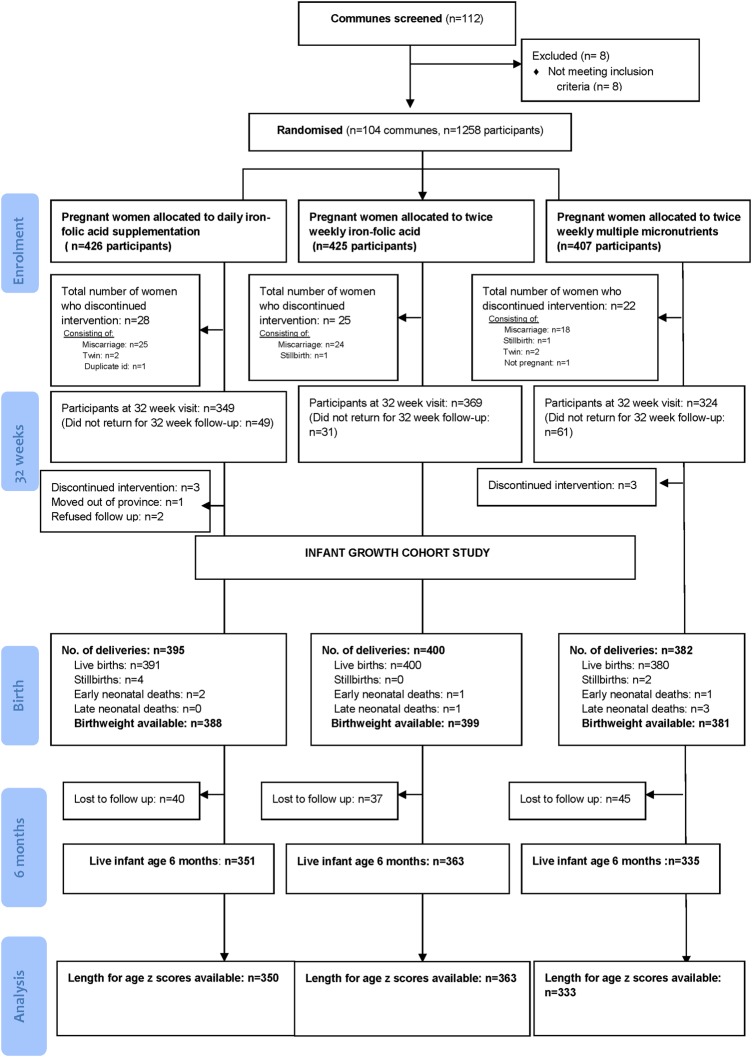

At 6 months of age visit, length-for-age z scores were available on 1046 infants. Baseline maternal and infant socio-economic, demographic, nutritional, biochemical, anthropometric and morbidity outcomes are presented in tables 1 and 2. There were no clinically significantly differences in baseline characteristics between infants with available length for age z scores and those in whom measurements were unavailable (see online supplementary table S1). Mean length-for-age z score at 6 months of age was −0.58 (SD 0.94), and prevalence of stunting at 6 months of age was 6.4% (95% CI 5.0% to 7.9%). Prevalence of underweight was 3.3% (95% CI 2.2% to 4.4%) and wasting was 1.6% (95% CI 0.71% to 2.16%). A flow diagram of the study is presented in figure 1.

Table 1.

Baseline maternal and infant socio-economic, demographic, nutritional, biochemical and anthropometric factors

| Maternal factors | Values |

|---|---|

| Demographic factors | |

| Wealth index* | 66.3 (0.09) |

| Maternal age (years)* (n=1046) | 26.7 (4.9) |

| Educational level† | |

| Primary school | 159/1046 (15.2) |

| Secondary school | 705/1046 (67.4) |

| University/college | 182/1046 (17.4) |

| Occupation† | |

| Farmer/housewife | 560/1046 (53.5) |

| Factory worker/trader | 350/1046 (33.5) |

| Government official/clerk | 136/1046 (13.0) |

| Anthropometric factors | |

| Height (cm)* (n=1045) | 153.6 (4.7) |

| Body mass index enrolment (kg/m2)* | 19.9 (2.0) |

| Body mass index group enrolment† | |

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 271/1045 (25.9) |

| Normal (18.5–25 kg/m2) | 759/1045 (72.6) |

| Overweight (>25 kg/m2) | 15/1045 (1.4) |

| Mid upper arm circumference enrolment (cm)* (n=1045) | 23.8 (2.1) |

| Weight gain during pregnancy (kg)* (n=958) | 8.19 (2.6) |

| Antenatal factors | |

| Gravidity† | |

| Primigravida | 326/1046 (31.2) |

| Multigravida | 720/1046 (68.8) |

| Type of supplement taken during pregnancy† | |

| Daily IFA supplements | 350/1046 (33.5) |

| Twice weekly IFA supplements | 363/1046 (34.7) |

| MMN supplements | 333/1046 (31.8) |

| Change of diet when pregnant† | |

| No | 259/1046 (24.8) |

| Yes | 787/1046 (75.2) |

| Meat intake during pregnancy at enrolment (number of times per week)* (n=1046) | 3.85 (2.26) |

| Persistent depression EPDS† | |

| No | 909/1046 (94.9) |

| Yes | 49/1046 (5.1) |

| Biochemical factors | |

| Haemoglobin enrolment (g/dL)* (n=1046) | 12.3 (1.2) |

| Haemoglobin 32 weeks (g/dL)* (n=948) | 12.4 (1.2) |

| Ferritin enrolment (μg/L)‡ (n=1042) | 77 (50 to 127) |

| Ferritin 32 weeks (μg/L)‡ (n=945) | 28 (17 to 42) |

| Iodine (μg/L)‡ (n=954) | 53 (30.6 to 87.3) |

| B12 enrolment‡ (pmol/L) (n=1043) | 394 (317 to 499) |

| B12 at 32 weeks‡ (pmol/L) (n=945) | 232 (187 to 285) |

| Folate enrolment‡ (nmol/L) (n=1041) | 28 (21.6 to 34.4) |

| Folate at 32 weeks‡ (nmol/L) (n=944) | 28.7 (22.4 to 33.5) |

| 25-(OH) vitamin D* (nmol/L) (n=891) | 70.6 (22.2) |

*Values are mean (SD).

†Values are number (%).

‡Values are median (25th–75th percentile).

IFA, iron-folic acid; MMN, multiple micronutrient; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.

Table 2.

Baseline infant nutritional, biochemical and anthropometric factors

| Infant factors | Values |

|---|---|

| Demographic factors | |

| Male sex* | 557/1045 (53.3) |

| Neonatal outcomes | |

| Birth weight (g)† | 3155 (393.7) |

| Birth length (cm)† | 49.2 (2.9) |

| Birth head circumference (cm)† | 32.7 (2.1) |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks)† | 39.1 (2.0) |

| 6-week outcomes | |

| Infant weight (g)† | 3154 (396.0) |

| Infant length (cm)† | 56.5 (3.7) |

| Infant head circumference (cm)† | 37.4 (2.1) |

| Dietary factors | |

| Continued breast feeding at 6 months of age* | 1045/1046 (99.9) |

| Exclusively breast fed at 6 months of age* | 191/1045 (18.3) |

| First introduction of complementary food (weeks)† | 17.2 (4.01) |

| Infant morbidity 6 weeks | |

| Infant diarrhoea* | 48/1038 (4.6) |

| Infant cough* | 123/1038 (11.9) |

| Infant fever* | 12/1038 (1.2) |

| Infant hospitalisation* | 75/1038 (7.2) |

| Infant morbidity 6 months | |

| Infant diarrhoea* | 421/1046 (40.3) |

| Infant cough* | 593/1046 (56.7) |

| Infant fever* | 265/1046 (25.3) |

| Infant hospitalisation* | 213/1046 (20.4) |

| Biochemical factors | |

| Infant haemoglobin (g/dL)† | 11.0 (1.1) |

| Infant ferritin (μg/L)‡ | 31 (17 to 53) |

*Values are number (%).

†Values are mean (SD).

‡Values are median (25th–75th percentile).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Univariable analyses

The results are presented in tables 3–5.

Table 3.

Associations between maternal factors in early pregnancy and infant length-for-age z scores at 6 months of age (univariable and multivariable regression)

| Univariable regression | Multivariable regression* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal factors | Coefficient (95% CI) | p Value | Coefficient (95% CI) | p Value |

| Demographic factors | ||||

| Maternal age (years) | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.02) | 0.18 | ||

| Education | ||||

| Primary school | Reference | |||

| Secondary school | 0.05 (−0.11 to 0.21) | 0.55 | 0.04 (−0.12 to 0.20) | 0.63 |

| University | 0.23 (0.03 to 0.43) | 0.03 | 0.18 (−0.12 to 0.20) | 0.07 |

| Gravidity | ||||

| Primgravida | Reference | – | ||

| Multigravida | 0.01 (−0.12 to 0.13) | 0.93 | ||

| Nutritional and health status | ||||

| Height (per 5 cm) | 0.25 (0.20 to 0.35) | <0.001 | 0.25 (0.20 to 0.35) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index at enrolment (kg/m2) | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.06) | 0.02 | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.07) | 0.01 |

| Mid upper arm circumference enrolment(cm) | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.07) | 0.01 | ||

| Depression on enrolment (EPDS) | ||||

| No | Reference | – | ||

| Yes | −0.12 (−0.26 to 0.03) | 0.11 | ||

| Antenatal practices | ||||

| Change of diet when pregnant | ||||

| No | Reference | – | ||

| Yes | 0.02 (−0.11 to 0.15) | 0.74 | ||

| Meat intake during pregnancy at enrolment (number of times per week) | 0.01 (−0.02 to 0.03) | 0.47 | ||

| Use of traditional supplements during pregnancy | −0.21 (−0.30 to 0.26) | 0.88 | ||

| Micronutrient status | ||||

| Haemoglobin enrolment (per 10 g/dL) | −0.10 (−0.60 to 0.40) | 0.63 | ||

| Ferritin enrolment (log2 μg/L)† | −0.04 (−0.12 to 0.04) | 0.33 | ||

| B12 enrolment (log2 pmol/L)† | 0.01 (−0.16 to 0.16) | 0.99 | ||

| Folate enrolment (log2 nmol/L)† | 0.13 (−0.01 to 0.27) | 0.07 | ||

*Model adjusted for maternal age, gravidity, gestational age at enrolment and trial intervention.

†Log2 transformed—regression coefficient represents mean change in infant length-for-age z score associated with a twofold change in ferritin, B12 or folate.

EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.

Table 4.

Associations between maternal factors in late pregnancy and infant length-for-age z scores at 6 months of age (univariable and multivariable regression)

| Univariable regression | Multivariable regression* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal factors in late pregnancy | Coefficient (95% CI) | p Value | Coefficient (95% CI) | p Value |

| Nutritional and health status | ||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) at 32 weeks gestation | 0.06 (0.03 to 0.09) | <0.001 | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.07) | 0.01 |

| Weight gain during pregnancy (kg) | 0.05 (0.03 to 0.07) | <0.001 | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.06) | 0.004 |

| Depression at 32 weeks' gestation (EPDS) | ||||

| No | Reference | – | ||

| Yes | −0.03 (−0.21 to 0.15) | 0.75 | ||

| Persistent depression (enrolment and 32 weeks) (EPDS) | ||||

| No | Reference | – | ||

| Yes | −0.22 (−0.49 to 0.04) | 0.10 | ||

| Change of diet at 32 weeks gestation | ||||

| No | Reference | – | ||

| Yes | −0.04 (−0.18 to 0.11) | 0.63 | ||

| Meat intake during pregnancy at 32 weeks gestation (no. times per week) | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02) | 0.54 | ||

| Use of traditional supplements during pregnancy | ||||

| No | Reference | – | ||

| Yes | −0.25 (−0.70 to 0.21) | 0.29 | ||

| Micronutrient status at 32 weeks | ||||

| Haemoglobin (per 10 g/dL) | −0.30 (−0.80 to 0.20) | 0.25 | ||

| Ferritin (log2 μg/L)† | −0.07 (−0.17 to 0.02) | 0.11 | ||

| B12 (log2 pmol/L)† | −0.16 (−0.34 to 0.02) | 0.08 | ||

| Folate (log2 nmo/L)† | −0.03 (−0.19 to 0.12) | 0.69 | ||

| Vitamin D (per 20 nmol/L) | −0.07 (−0.12 to −0.01) | 0.02 | −0.06 (−0.11 to −0.001) | 0.04 |

| Urinary iodine (log2 μg/L)† | −0.02 (−0.09 to 0.05) | 0.56 | ||

*Model adjusted for maternal age, gravidity, gestational age at enrolment, infant sex and trial intervention.

†log2 transformed—regression coefficient represents mean change in infant length-for-age z score associated with a twofold change in ferritin, B12, folate or iodine.

EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.

Table 5.

Associations between early infant factors and infant length-for-age z scores at 6 months of age (univariable and multivariable regression)

| Univariable regression | Multivariable regression* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early infant factors | Coefficient (95% CI) | p Value | Coefficient (95% CI) | p Value |

| Neonatal factors | ||||

| Birth weight (per 100 g) | 0.09 (0.07 to 0.10) | <0.001 | 0.10 (0.09 to 0.12) | <0.001 |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 0.11 (0.08 to 0.14) | <0.001 | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.07) | 0.02 |

| Male sex | −0.19 (−0.31 to −0.08) | 0.001 | −0.31 (−0.43 to −0.20) | <0.001 |

| Six-week anthropometric measurements† | ||||

| Infant length (cm) | 0.09 (0.08 to 0.11) | <0.001 | 0.09 (0.08 to 0.11) | <0.001 |

| Infant weight (kg) | 0.90 (0.77 to 1.03) | <0.001 | ||

| Infant head circumference | 0.07 (0.04 to 0.10) | <0.001 | ||

| Infant health status 6 weeks of age† | ||||

| Respiratory illness | −0.22 (−0.40 to −0.04) | 0.02 | −0.20 (−0.38 to −0.02) | 0.02 |

| Fever | −0.35 (−0.89 to 0.18) | 0.20 | ||

| Diarrhoea | 0.03 (−0.25 to 0.30) | 0.85 | ||

| Hospitalisation | −0.40 (−0.62 to −0.18) | <0.001 | −0.25 (−0.47 to −0.03) | 0.03 |

| Infant health status 6 months of age | ||||

| Respiratory illness | −0.10 (−0.21 to 0.02) | 0.10 | ||

| Fever | −0.22 (−0.35 to −0.09) | 0.001 | ||

| Diarrhoea | −0.05 (−0.17 to 0.07) | 0.39 | ||

| Hospitalisation | −0.28 (−0.42 to −0.14) | <0.001 | −0.22 (−0.41 to −0.04) | 0.02 |

| Child care practices | ||||

| Exclusive breast feeding at 6 weeks of age | 0.03 (−0.09 to 0.15) | 0.60 | ||

| Exclusive breast feeding at 6 months of age | −0.08 (−0.23 to 0.06) | 0.26 | ||

| Timing of introduction of complementary food (weeks) | 0.01 (−0.009 to 0.03) | 0.07 | ||

| Use of formula at 6 weeks of age | −0.03 (−0.15 to 0.09) | 0.62 | ||

| Use of formula at 6 months of age | −0.11 (−0.30 to 0.08) | 0.27 | ||

| Use of dietary supplements for child in the first 6 months | 0.29 (0.11 to 0.47) | 0.001 | 0.25 (0.07 to 0.43) | 0.01 |

| Micronutrient status at 6 months of age | ||||

| Haemoglobin (per 10 g/dL) | 0.10 (−0.40 to 0.60) | 0.75 | ||

| Ferritin (log2 μg/L)‡ | −0.08 (−0.15 to −0.01) | 0.02 | −0.19 (−0.25 to −0.12) | <0.001 |

*Model adjusted for maternal age, gravidity, gestational age at enrolment and trial intervention.

†Variables at the 6 -week time point have been included in separate multivariable regression models as they are on the causal pathway between birth weight and length-for-age z scores at 6 months of age.

‡log2 transformed—regression coefficient represents mean change in infant length-for-age z score associated with a twofold change in ferritin.

Multivariable analyses

The results of adjusted models are presented in tables 3–5.

Maternal factors

Maternal body mass index (BMI) at enrolment (estimated coefficient 0.04/kg/m2, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.07) and weight gain during pregnancy (0.04/kg, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.06) were positively associated with infant length-for-age z scores at 6 months of age. There was an inverse association with 25-(OH) vitamin D concentration in late pregnancy (−0.06 per 20 nmol/L, 95% CI −0.11 to −0.001). No association between maternal iodine and infant length-for-age z scores was demonstrated (estimated coefficient −0.02 per twofold increase in iodine, 95% CI −0.09 to 0.05).

Maternal risk factors associated with infant birth weight are presented in online supplementary tables S2 and S3. Maternal haemoglobin (estimated coefficient of −268 g per 10 g/dL, 95% CI −459 to −76) and ferritin (−66.7 g per twofold increase in ferritin, 95% CI −104.1 to −29.2) levels at 32 weeks gestation were inversely associated with infant birth weight. Mean birth weight was significantly lower in infants born to women with serum ferritin concentrations in the highest quartile (43–273 μg/L) compared with those born to women with ferritin concentrations in the lowest quartile (4–17 μg/L) (estimated coefficient −106.4 g, 95% CI −174.9 to −38.0).

Early infant factors

Birth weight (estimated coefficient of 0.10 per 100 g increase in birth weight, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.12), gestational age at birth (0.04 per 1 week increase in gestational age, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.07) and use of dietary supplements in the child (0.25, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.43) were positively associated with infant length-for-age z scores at 6 months of age. Infant sex (males vs females; −0.31, 95% CI −0.43 to −0.20), infant ferritin concentration (−0.19 per twofold increase in ferritin, 95% CI −0.25 to −0.12) and hospitalisation within the first six months of life (−0.22, 95% CI −0.41 to −0.04) were found to be inversely associated with length-for-age z scores at 6 months of age.

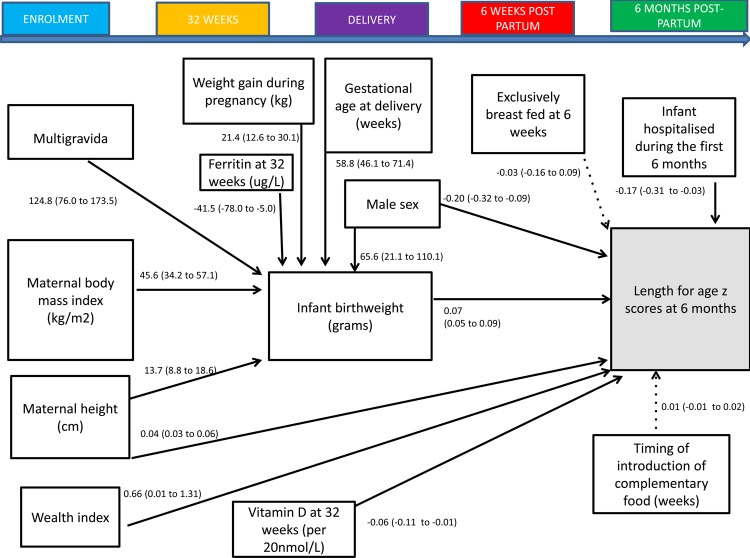

Structural equation model

A structural equation model predicting infant length-for-age z scores is shown in figure 2 and table 6. This model presents a theoretical causal path between maternal socio-economic factors, nutritional and micronutrient status during pregnancy and highlights the role of infant birth weight as a predictor of infant growth in the first six months of life. The model demonstrates that maternal BMI, weight gain during pregnancy, gestational age at delivery and maternal ferritin concentration at 32 weeks gestation were indirectly associated with length-for-age z scores via infant birth weight, whereas there was a direct association with maternal height, 25-(OH) vitamin D concentration in late pregnancy, infant sex and hospitalisation in the first six months of life. The model fits the data well (χ2 p value 0.16, CFI=0.990, RMSEA=0.02 with 0.96 probability of RMSEA being ≤0.05).

Figure 2.

Structural equation model of factors occurring during pregnancy and early infancy influencing infants’ length-for-age z scores at 6 months of age. All of the variables in the diagram are observed. Single-headed solid arrows represent statistically significant directional paths at a significance level of 0.05. Dotted lines indicate hypothesised but non-significant paths. Path coefficients are linear regression coefficients and 95% CIs representing the variables with direct relationships with infant birth weight or length-for-age z scores at 6 months of age.

Table 6.

Structural equation model for maternal (early and late pregnancy) and infant factors associated with infant length-for-age z scores at 6 months of age

| Indirectly associated with infant length-for-age z scores through birth weight (g) | Coefficient (95% CI)* | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal factors | ||

| Demographic factors | ||

| Gravidity | ||

| Primigravida | Reference | |

| Multigravida | 124.8 (76.0 to 173.5) | <0.001 |

| Nutritional and health status | ||

| Height at enrolment (per 5 cm) | 68.5 (44 to 93) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index at enrolment (kg/m2) | 45.6 (34.2 to 57.1) | <0.001 |

| Gestational weight gain (kg) | 21.4 (12.6 to 30.1) | <0.001 |

| Micronutrient factors | ||

| Ferritin at 32 weeks (log2 μg/L)† | −41.5 (−78.0 to −5.0) | 0.03 |

| Infant factors | ||

| Male sex | 65.6 (21.1 to 110.1) | 0.004 |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 58.8 (46.1 to 71.4) | <0.001 |

| Directly associated with infant length-for-age z scores | Coefficient (95% CI)‡ | p Value |

| Maternal factors | ||

| Demographic factors | ||

| Wealth index | 0.66 (0.01 to 1.31) | 0.05 |

| Nutritional factors | ||

| Height at enrolment (cm) | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.06) | <0.001 |

| Micronutrient factors | ||

| Vitamin D at 32 weeks (per 20 nmol/L) | −0.06 (−0.11 to −0.01) | 0.03 |

| Infant factors | ||

| Birth weight (per 100 g) | 0.07 (0.05 to 0.09) | <0.001 |

| Infant hospitalisation | −0.17 (−0.31 to −0.03) | 0.02 |

| Male sex | −0.20 (−0.32 to −0.09) | <0.001 |

*Regression coefficient represents estimated mean change in birth weight (g) associated with the maternal or infant factor (note for ferritin this is for a twofold increase in ferritin levels).

†log2 transformed—regression coefficient represents mean change in infant birth weight associated with a twofold change in ferritin.

‡Regression coefficient represents estimated mean change in length-for-age z score associated with the maternal or infant factor.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest study to present a comprehensive overview of maternal and early infant predictive factors for infant growth in Southeast Asia. Using structural equation modelling, we were able to identify factors that were directly associated with infant length-for-age z scores at 6 months of age and those that were indirectly associated through infant birth weight. Significantly, we found that maternal antenatal ferritin levels were inversely associated with infant growth at 6 months of age and that this was mediated through infant birth weight.

Physiologically normal maternal iron status has been shown to play an important role in reducing the risk of preterm delivery and low-birthweight infants.15 However, recent findings indicate that adverse pregnancy outcomes may also occur in association with high haemoglobin and serum ferritin concentrations, including fetal growth restriction, preterm delivery, low birth weight and pre-eclampsia.16 This may be explained by increased oxidative stress, failure of expansion of the maternal plasma volume or increased risk of intrauterine infection.17–20 Our finding that higher late gestational ferritin stores were indirectly associated with reduced length-for-age Z scores at 6 months of age through birth weight extend those of Lao et al,21 who demonstrated an inverse association between serum ferritin and infant birth weight in an observational study of 488 pregnant women with baseline haemoglobin ≥10 g/dL.

We also found a negative association between infant ferritin and length-for-age z scores. Although a recent meta-analysis concluded that infant iron supplementation had no effect on growth,22 several studies have documented a negative impact on the linear growth of children during or following iron supplementation.23 24 Our findings require further exploration and highlight the need for caution in administrating daily iron to non-anaemic pregnant women and infants who already have sufficient iron stores. This is particularly important in many countries where rapid economic development has been associated with a reduction in the prevalence of anaemia and iron deficiency in pregnant women.25

We observed an inverse relationship between length-for-age z scores at 6 months of age and maternal 25-(OH) vitamin D, although the estimated magnitude of change associated with an increase in 25-(OH) vitamin D of 20 nmol/L was small (−0.06 per 20 nmol/L).26 Leffelaar et al27 demonstrated accelerated growth in length during an infant's first year of life in infants born to mothers with 25-(OH) vitamin D <30 nmol/L and postulated that this may be due to increasing 25-(OH) vitamin D levels postnatally either through micronutrient supplementation or fortified bottle feeds. Other studies have shown no differences in weight or height across quartiles of 25-(OH) vitamin D status during infancy.28 29

The positive association between BMI/gestational weight gain and infant growth is likely to be due to restricted intrauterine blood flow leading to reduced uterine and placental growth, and increased risk of intrauterine growth retardation and low birth weight,30–32 both of which have been shown to be important contributors to stunting in childhood.4 We also found that hospitalisation had a negative effect on early infant growth. In addition to the adverse effects of disease, hospitalisation may interfere with a mother's ability to breast feed or provide other care-giving practices.4

Strengths of our study include the large sample size, rigorous trial design of the original cluster randomised controlled trial and use of structural equation modelling to determine whether variables were directly or indirectly associated with infant growth. Our study was conducted in a rapidly developing rural area, representative of many areas of Vietnam, and thus our findings are likely to be generalisable to other parts of the country. Although our study was set in the context of a clinical trial of micronutrient supplementation, we found no evidence for modification of associations by trial intervention arm. A limitation of studying predictors of growth within a clinical trial context is that participants in a trial may not be representative of the rest of the population. Other limitations of the study were that the volume of blood that could be acceptably collected from infants was limited, leading to only 88% of infants with infant ferritin results at 6 months of age. As well, the passive method used to collect information on infant illness and hospitalisation may have introduced recall bias, although it is likely that mothers would have been able to recall periods of hospitalisation.

There is mounting evidence that fetal undernutrition in middle-to-late gestation leads to disproportionate fetal growth and persisting changes in blood pressure, cholesterol metabolism, insulin responses to glucose and other metabolic parameters, resulting in the programming of chronic diseases such as hypertension, coronary heart disease and high cholesterol, later in life.33–35 The pathways identified in this study will assist with appropriate targeting of future maternal and infant interventions and provide a framework to inform policy measures for early prevention of chronic undernutrition in children in rural Vietnam.

Conclusion

Maternal nutritional status is an important predictor of early infant growth. Our finding of a potential deleterious effect of higher maternal and infant iron stores on infant growth requires further exploration and suggests a cautious approach to iron supplementation during the antenatal and early infancy periods in populations with low rates of iron deficiency. Future research should also explore the role of maternal 25-(OH) vitamin D in child growth and development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants and health workers in Ha Nam Province; the Ha Nam Provincial Centre of Preventive Medicine; the Viet Nam Ministry of Health; Research and Training Centre for Community Development (RTCCD); and those involved in the original cluster randomised trial study design9; Beth Hilton-Thorp (LLB) and Christalla Hajisava for Departmental support; and Alfred Pathology.

Footnotes

Contributors: SH, B-AB, JF and TT conceived the study idea and designed the study. TTH, NCK and DDT coordinated and supervised data collection at all sites. SH, TTH and TDT designed the data collection instruments. TTH, TTT and NCK collected the data. SH reviewed the literature. JAS directed the analyses, which were carried out by SH and AMdL. All authors participated in the discussion and interpretation of the results. SH organised the writing and wrote the initial drafts. All authors critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final version.

Funding: The original cluster randomised trial was funded by a grant from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (grant number 628751).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Melbourne Health Human Research Ethics Committee, and the HaNam Provincial Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data from the study would be available if authors are contacted subject to agreements within the ethical approvals for the study.

References

- 1.Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet 2008;371:243–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet 2008;371:340–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Victora CG, de Onis M, Hallal PC, et al. Worldwide timing of growth faltering: revisiting implications for interventions. Pediatrics 2010;125:e473–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013;382:427–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Rizvi A, et al. Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost? Lancet 2013;382:452–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organisation. Global Database on Child Growth and Malnutrition: Vietnam. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institute of Nutrition. Summary Report, General Nutrition Survey, 2009–2010. Hanoi: National Institute of Nutrition, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Nations Children's Fund. Composition of a multi-micronutrient supplement to be used in pilot programmes among pregnant women in developing countries. Report of a UNICEF/WHO/UNU Workshop. New York: United Nations Children's Fund, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanieh S, Ha TT, Simpson JA, et al. The effect of intermittent antenatal iron supplementation on maternal and infant outcomes in rural Viet Nam: a cluster randomised trial. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seager JR, de Wet T. Establishing large panel studies in developing countries: the importance of the ‘Young Lives’ pilot phase. London, UK: Young Lives Working Paper No. 9, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organisation. WHO Anthro (version 3.2.2, January 2011) and macros, 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organisation. The WHO Child Growth Standards, 2012. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acock A. Discovering Structural Equation Modeling Using Stata. 1st edn Texas: Stata Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen MR. Structural Equation Modelling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit. Electron J Bus Res Methods 2008;6:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pena-Rosas JP, Viteri FE. Effects and safety of preventive oral iron or iron+folic acid supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(4):CD004736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scholl TO. Iron status during pregnancy: setting the stage for mother and infant. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;81:1218S–22S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu WY, Wu CH, Hsieh CT, et al. Low body weight gain, low white blood cell count and high serum ferritin as markers of poor nutrition and increased risk for preterm delivery. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2013;22:90–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scholl T. High third-trimester ferritin concentration: associations with very preterm delivery, infection, and maternal nutritional status. Obstet Gynecol 1998;92:161–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao R, Sorensen TK, Frederick IO, et al. Maternal second-trimester serum ferritin concentrations and subsequent risk of preterm delivery. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2002;16:297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casanueva E, Viteri FE. Iron and oxidative stress in pregnancy. J Nutr 2003;133(5 Suppl 2):1700S–08S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lao TT, Tam KF, Chan LY. Third trimester iron status and pregnancy outcome in non-anaemic women; pregnancy unfavourably affected by maternal iron excess. Hum Reprod 2000;15:1843–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vucic V, Berti C, Vollhardt C, et al. Effect of iron intervention on growth during gestation, infancy, childhood, and adolescence: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Nutr Rev 2013;71:386–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sachdev H, Gera T, Nestel P. Effect of iron supplementation on mental and motor development in children: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Public Health Nutrition 2005;8:117–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahman MM, Akramuzzaman SM, Mitra AK, et al. Long-term supplementation with iron does not enhance growth in malnourished Bangladeshi children. J Nutr 1999;129:1319–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thurnham D. Micronutrient status in Vietnam. Comparisons and contrasts with Thailand and Cambodia. Sight Life 2012;26:56–67. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanieh S, Ha TT, Simpson JA, et al. Maternal vitamin d status and infant outcomes in rural Vietnam: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One 2014; 9:e99005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leffelaar ER, Vrijkotte TG, van Eijsden M. Maternal early pregnancy vitamin D status in relation to fetal and neonatal growth: results of the multi-ethnic Amsterdam Born Children and their Development cohort. Br J Nutr 2010;104:108–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prentice A, Jarjou LM, Goldberg GR, et al. Maternal plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration and birthweight, growth and bone mineral accretion of Gambian infants. Acta Paediatr 2009;98:1360–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vieth Streym S, Kristine Moller U, Rejnmark L, et al. Maternal and infant vitamin D status during the first 9 months of infant life-a cohort study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2013;67:1022–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsai IH, Chen CP, Sun FJ, et al. Associations of the pre-pregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain with pregnancy outcomes in Taiwanese women. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2012;21:82–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drehmer M, Duncan BB, Kac G, et al. Association of second and third trimester weight gain in pregnancy with maternal and fetal outcomes. PLoS One 2013;8:e54704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gernand AD, Christian P, Paul RR, et al. Maternal weight and body composition during pregnancy are associated with placental and birth weight in rural Bangladesh. J Nutr 2012;142:2010–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barker DJ. Fetal origins of coronary heart disease. BMJ 1995;311: 171–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balbus JM, Barouki R, Birnbaum LS, et al. Early-life prevention of non-communicable diseases. Lancet 2013;381:3–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Bateson P, et al. Towards a new developmental synthesis: adaptive developmental plasticity and human disease. Lancet 2009;373:1654–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.