Background: PINK1 mutations affect mitochondrial homeostasis and cause Parkinson disease.

Results: PINK1 is phosphorylated on the outer mitochondrial membrane. We show here that phosphorylation of serines 228 and 402 increases the capacity of PINK1 to phosphorylate its substrates Parkin and Ubiquitin.

Conclusion: PINK1 phosphorylation regulates its kinase activity.

Significance: Understanding PINK1 regulation is pivotal to unravel its mitochondrial function.

Keywords: Mitochondria, Neurodegenerative Disease, Parkinson Disease, Posttranslational Modification (PTM), Protein Phosphorylation, PTEN-induced Putative Kinase 1 (PINK1), Serine/Threonine Protein Kinase

Abstract

Mutations in the PINK1 gene cause early-onset recessive Parkinson disease. PINK1 is a mitochondrially targeted kinase that regulates multiple aspects of mitochondrial biology, from oxidative phosphorylation to mitochondrial clearance. PINK1 itself is also phosphorylated, and this might be linked to the regulation of its multiple activities. Here we systematically analyze four previously identified phosphorylation sites in PINK1 for their role in autophosphorylation, substrate phosphorylation, and mitophagy. Our data indicate that two of these sites, Ser-228 and Ser-402, are autophosphorylated on truncated PINK1 but not on full-length PINK1, suggesting that the N terminus has an inhibitory effect on phosphorylation. We furthermore establish that phosphorylation of these PINK1 residues regulates the phosphorylation of the substrates Parkin and Ubiquitin. Especially Ser-402 phosphorylation appears to be important for PINK1 function because it is involved in Parkin recruitment and the induction of mitophagy. Finally, we identify Thr-313 as a residue that is critical for PINK1 catalytic activity, but, in contrast to previous reports, we find no evidence that this activity is regulated by phosphorylation. These data clarify the regulation of PINK1 through multisite phosphorylation.

Introduction

Protein phosphorylation regulates enzymatic activity and signal transduction in the cell. Impaired phosphorylation contributes to many diseases, including the neurodegenerative disorder Parkinson disease (PD).4 Several genetic forms of PD are caused by mutations in kinase-encoding genes (1), including PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1, GeneID 65018). PINK1 encodes a serine/threonine kinase with a mitochondrial targeting sequence, and mutations in this gene are linked to early-onset recessive PD (2). Cellular and animal loss of PINK1 function models show defects in mitochondrial homeostasis (3–5), impaired stress response (6–8), decreased oxidative phosphorylation (9–12), and defects in mitochondrial trafficking (13, 14), dynamics (15–17) and quality control (18, 19).

One of the most studied roles of PINK1, however, is the regulation of mitophagy, the autophagic removal of defective mitochondria (18, 19). Depolarization triggers the accumulation of PINK1 on the outside of the mitochondria (18) where it phosphorylates Parkin, a PD-linked E3 ubiquitin ligase (20), Ubiquitin (21–23), and Mitofusin 2 (24). This leads to ubiquitination of the defective organelle and mitophagic removal.

Recently, PINK1 has been reported to be autophosphorylated upon depolarization, hinting at a possible activation mechanism (25, 26). Different residues have been identified as autophosphorylation sites after CCCP-induced mitochondrial membrane depolarization, namely Ser-228, Thr-257, and Ser-402 (20, 27). Two residues, Ser-228 and Ser-402, appear to be involved in PINK1 dimerization and Parkin recruitment (27, 28). A fourth putative phosphorylation site in PINK1 is Thr-313, a residue that is regulated by the activity of microtubule affinity regulating kinase 2 (MARK2) (29, 30).

Although understanding the regulation of PINK1 activity is pivotal to interpret how PINK1 executes its different functions in both healthy and depolarized mitochondria, it remains rather unclear how and where in the cell phosphorylation at any of these four sites occurs and regulates PINK1 catalytic activity. In this study, we analyze the phosphorylation status of PINK1 under basal and depolarizing conditions at the mitochondria and employ an in vitro kinase assay using purified human PINK1 to measure (auto)phosphorylation. We find that the previously identified phosphorylation sites Ser-228, Thr-257, Thr-313, and Ser-402 vary dramatically in their involvement in autophosphorylation and in their roles in regulation of PINK1 kinase activity and substrate phosphorylation in vitro. We further investigate the consequences of PINK1 phosphorylation for Parkin recruitment.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids

Full-length cDNA of human PINK1 was obtained from Origene and cloned into pcDNA3.1-V5/His-TOPO according to the protocol of the manufacturer (Invitrogen). The 3×FLAG/Strep tag was amplified via PCR (31) and cloned on the C terminus of PINK1 in the pcDNA3.1 vector. Mutant PINK1 constructs were generated by QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis (Agilent Technologies) according to the guidelines of the manufacturer. To obtain kinase-inactive (KI) PINK1, lysine 219 in the ATP-binding pocket and aspartic acid 362 in the catalytic core were both mutated to alanine (K219A/D362A). For each of the reported phosphosites on PINK1 (serine 228, threonine 257, threonine 313, and serine 402), constructs were generated with mutations to aspartic acid or glutamic acid (phosphomimetic) and alanine (phosphodead), referred to as S228D, S228E, and S228A, etc. PINK1 harboring a mutation at each of these four sites is referred to as quadruple mutant PINK1 (4×D, 4×E, and 4×A). PINK1 phosphomutants were also cloned into the pMSCV retroviral vector. A truncated form (ΔN) of PINK1 in pcDNA3.1 was created by PCR amplification of the PINK1 sequence from amino acids 113–581 and subsequent TOPO cloning according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen).

The Ubiquitin-like binding domain (Ubl) of Parkin was obtained by PCR amplification of amino acids 1–108 from the pCMV-Parkin plasmid (Origene). The PCR product was further cloned into pGEX-4T-1 (Addgene) in-frame with the N-terminal GST-tagged fusion construct. All plasmids were confirmed by performing sequencing analysis.

Cell Culture and Stable Cell Lines

HEK, HeLa, COS, and mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen). HEK, COS, and HeLa cells were transfected using TransIT transfection reagent (Mirus Bio) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Briefly, 1 μg of DNA plasmid per 3 μl of transfection reagent ratio was used. Stable cell lines expressing PINK1 harboring WT or quadruple mutant PINK1 were generated by retroviral transduction of immortalized MEFs derived from PINK1 KO mice (9) and PARL KO mice (32). At 30–40% confluence, the MEFs were transduced using a replication-defective recombinant retroviral expression system (Clontech) with either WT or quadruple mutant PINK1-FLAG in the PINK1 KO MEFs, and PINK1-V5 in the case of PARL KO MEFs. Cell lines stably expressing the desired proteins were selected on the basis of their acquired resistance to 5 μg/ml puromycin.

PINK1 KO HeLa cells were generated using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/Cas technology (33). A target sequence was selected from the first exon spanning the start codon of PINK1 (CGCCACCATGGCGGTGCGAC). This target sequence was cloned in pX330-U6-Chimeric_BB-CBh-hSpCas9 (Addgene), and the plasmid was transfected in WT HeLa cells. Transfected cells were seeded at single cell density, and PINK1 expression in each clone was analyzed via Western blot analysis. Selected clones in which PINK1 expression was absent were subjected to MiSeq Next Generation sequencing analysis (Illumina) for the PINK1 gene sequence and the top five off-target regions in the HeLa genome for the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats guide RNA. Results showed an 84-bp deletion spanning the start codon of PINK1 on all chromosomal copies. The five strongest predicted off-targets sites in the HeLa genomic DNA were not cleaved by Cas9.

To induce mitochondrial membrane depolarization, MEF, HEK, and HeLa cells were treated with 10 μm CCCP for 3 h. Proteasomal inhibition was induced by treating MEF cells with 10 μm lactacystin for 3 h.

Mitochondrial Fractionation

Cells were collected and homogenized in isolation buffer (10 mm Tris-MOPS (pH 7.4), 0.5 mm EGTA-Tris (pH 7.4), and 0.2 m sucrose) at 1000 rpm using a Teflon pestle for 30 strokes. Cell debris was pelleted at 600 × g for 10 min. The supernatant (postnuclear or homogenate fraction) was centrifuged at 7000 × g to separate the mitochondrially enriched fraction (pellet) from the mitochondria-depleted or cytosol-enriched fraction (supernatant). The pellet was subsequently washed in isolation buffer and recentrifuged at 7000 × g for 10 min. Protein concentration was measured using a Bradford assay (Thermo Scientific).

Na2CO3 Extraction

Na2CO3 extraction of the mitochondrial fraction was performed by resuspending a three times snap-freeze-thawed mitochondrial pellet in freshly prepared Na2CO3 (0.1 m, pH 11.5). After incubation on ice for 30 min, membrane-associated proteins were separated by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 30 min. The pellet was resuspended in 0.1 m Na2CO3 (pH 11.5) and subjected to an incubation on ice and centrifugation (34). Supernatants (containing extracted proteins) of both centrifugation steps were pooled, and the pellet was resuspended in STE buffer (0.1 m NaCl, 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and 1 mm EDTA (pH 8.0)) containing 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors (Roche).

Proteinase K Accessibility Assay

Mitochondria were subjected to proteinase K (PK) digestion (35). Briefly, 100 μg/ml PK (Roche) was applied under the following buffer conditions: isolation buffer (10 mm Tris-MOPS (pH 7.4), 0.5 mm EGTA-Tris, and 0.2 m sucrose) and hypotonic medium (20 or 2 mm HEPES as indicated) with or without 0.3% Triton X-100. All samples were incubated with end-over-end rotation at 4 °C for 30 min. PK was inactivated, and proteins were precipitated with tricholoroacetic acid (Sigma). All samples were incubated for 15 min at room temperature in tricholoroacetic acid at 10% final concentration. After centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 10 min, protein pellets were resuspended in lithium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer (Invitrogen) with 4% β-mercaptoethanol and adjusted to neutral pH using Tris-HCl (pH 11).

Protein Dephosphorylation

Mitochondrially enriched fractions were lysed in PBS with 1% n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside and protease inhibitors (Roche). The mitochondrial lysate was incubated at 30 °C for 1 h with 200 units λ protein phosphatase (LPP) in a total reaction volume of 50 μl following the instructions of the manufacturer (New England Biolabs). Purified PINK1 bound to FLAG beads was dephosphorylated either prior to or after the in vitro kinase assay by incubation at 30 °C for 15 min with 800 units of LPP (New England Biolabs) in a total volume of 20 μl.

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting on Tris Acetate and Phos-Tag Gels

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on NuPage 7% Tris acetate gels (Invitrogen) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Gel electrophoresis was performed at 150 V for 1 h 20 min to allow optimal separation of different PINK1 forms.

For analysis on Phos-Tag gels, samples were incubated for 10 min at 70 °C in Tris/glycine SDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) with 4% β-mercaptoethanol. Resolution gels with 7.5% acrylamide (Acryl/Bis 29:1), 50 μm Phos-TagTM AAL-107 (Wako Chemicals) and 100 μm MnCl2 were casted according to the instructions of the manufacturer, including 4.5% acrylamide stacking gels. Mn2+-Phos-TagTM interacts with phosphorylated proteins, altering their migration pattern. Prior to transfer to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, gels were washed for 10 min with gentle shaking in transfer buffer containing 1 mm of EDTA to eliminate the manganese.

The following antibodies were used at the indicated dilutions: mouse anti-FLAGM2 (Sigma, 1:5000 dilution), mouse anti-V5 (Invitrogen, 1:5000 dilution), rabbit anti-PARL (Ref. 32, 1:5000 dilution), rabbit anti-PINK1 (catalog no. BC100-494, Novus Biologics, 1:1000 dilution), mouse anti-HSP60 (BD Biosciences, 1:5000 dilution), rabbit anti-HtrA2 (R&D Systems, 1:1000 dilution), rabbit anti-TOM20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:1000 dilution), rabbit anti-GST (Invitrogen, 1:5000 dilution), mouse anti-His (Invitrogen, 1:2000 dilution), mouse anti-Ubiquitin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:2000 dilution), and goat anti-mouse HRP and goat anti-rabbit HRP (Bio-Rad, 1:10,000 dilution). Signals were detected using ECL chemiluminescence with a Fujifilm LAS-4000 imager.

Purification of Active PINK1 and in Vitro Kinase Assay

The procedure for PINK1 purification and the kinase assay was adapted from (36). Briefly, COS cells were transfected with pcDNA-3.1-hPINK1-3×FLAG/Strep using TransIT transfection reagent (Mirus Bio) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. 48 h after transfection, cells were harvested and lysed in 25 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm NaF, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm MnCl2, 0.5% Igepal, mammalian protease inhibitors (Sigma), Complete protease inhibitor (Roche), 50 mg/liter DNase, 50 mg/liter RNase, and 1 mm DTT and homogenized using a 22-gauge needle in 5 strokes. After 25 min of centrifugation at 20,000 × g, the cleared lysate was incubated with FLAG magnetic beads (Sigma) at 4 °C for 45 min. The unbound fraction was separated by magnetic force and removed, and the beads were washed two times in lysis buffer, followed by three washes with kinase assay buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 3 mm MnCl2, and 0.5 mm DTT).

Kinase assays were performed immediately after purification, with PINK1-FLAG bound on beads and 1–2 μg of recombinant substrate protein and 100 μm ATP containing 5μCi [γ32P]ATP in kinase assay buffer containing 10 mm DTT for autophosphorylation and Parkin substrate phosphorylation or 0.5 mm DTT for ubiquitin substrate phosphorylation. Reactions were incubated at 22 °C while shaking at 14,000 rpm for 1 h. After incubation, PINK1 was eluted from the beads by incubation in NuPage lithium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer (Invitrogen) with 4% β-mercaptoethanol at 70 °C for 10 min and vortexing twice. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. Incorporation of radiolabeled phosphor was assessed via a storage phosphor screen and development on Typhoon FLA-7000.

Substrate Expression and Purification

BL21 bacteria were transformed with N-terminally GST-tagged Ubl Parkin in pGEX-4T-1, where protein expression was induced using 100 μm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside, and bacteria were incubated at 37 °C with 280 rpm for 2 h. Bacterial pellets were lysed in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mm EDTA, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.2 mm PMSF, and 1 mm benzamidine and purified using glutathione-SepharoseTM 4B (GE Healthcare) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

The Ubiquitin-His substrate was obtained commercially from Sigma-Aldrich. The quality and purification of all substrates was assessed via SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie staining and immunoblotting with anti-GST and anti-His for Ubl Parkin and Ubiquitin, respectively.

Parkin Recruitment

HeLa cells were seeded on 13-mm coverslips and transfected at ±60% confluence with Parkin-GFP and pMSCV-hPINK1-3×FLAG plasmids. 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with 10 μm CCCP for 3 h or an equivalent volume of DMSO as a control. Cells were washed three times in PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, washed three times in PBS, and permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min, followed by three washes in PBS. Cells were blocked in blocking buffer (0.2% gelatin, 2% fetal bovine serum, 2% BSA, 0.3% bovine serum albumin, 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS) with 5% donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) for 1 h. They were stained using the following primary antibodies at the indicated dilutions: 1:500 Turbo-GFP (Evrogen), 1:500 FLAGM2 (Sigma), and 1:500 cytochrome c (Sigma) for 2 h. After three washes in PBS, they were incubated with secondary antibodies: 1:500 Alexa Fluor 647 donkey anti-mouse, Alexa Fluor 555 donkey anti-sheep, and Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit (Invitrogen). Images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM confocal microscope using a ×60 objective and analyzed with ImageJ software.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical significance of differences between a set of two groups was evaluated using one-way analysis of variance followed by post hoc Dunnett's test (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ns, nonspecific). Results are depicted as mean ± S.E. of a minimum of three independent replicates.

RESULTS

PINK1 Is Phosphorylated at the Outer Mitochondrial Membrane

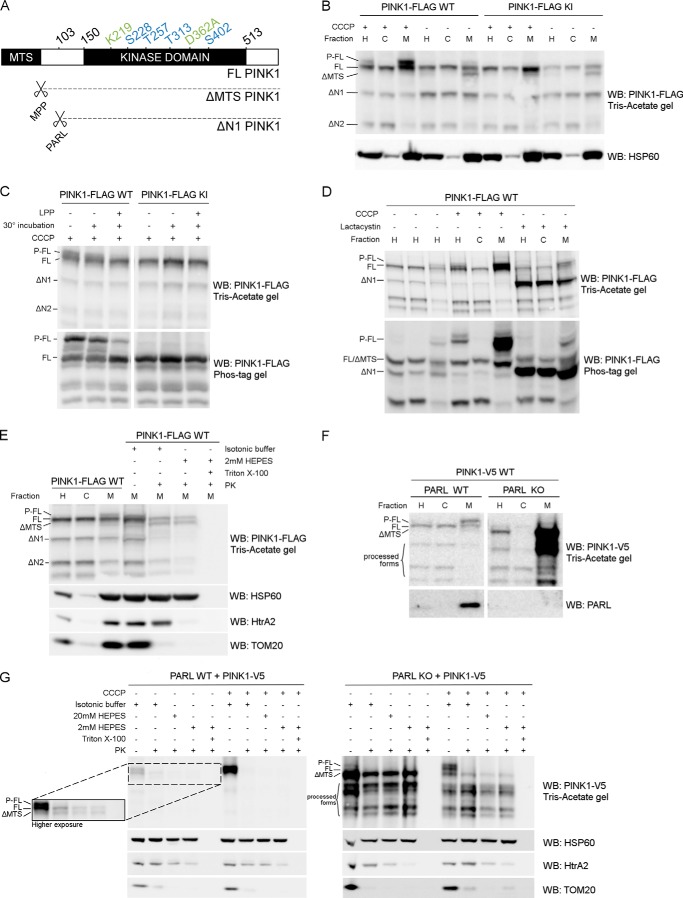

PINK1 accumulates under different conditions and has been reported to be phosphorylated upon depolarization (27, 37). To clarify how exactly PINK1 processing and phosphorylation are related, we expressed human PINK1 with a C-terminal FLAG tag in HEK293T cells and analyzed its expression pattern in the postnuclear cell homogenate (H), the mitochondrially depleted or cytoplasm-enriched (C), and the mitochondrially enriched (M) fractions (Fig. 1B). Under basal conditions, full-length (FL) PINK1 is targeted to the mitochondria, where it is processed by mitochondrial processing peptidase (MPP) (38), resulting in the cleavage of the mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS) and the detection of ΔMTS PINK1 in the mitochondrial fraction. Subsequent N-terminal processing by other proteases, including PARL and m-AAA (matrix-localized ATPases associated with diverse cellular activities) (38–40), leads to the appearance of further processed PINK1 forms ΔN1 and ΔN2 PINK1 (Fig. 1, A and B). When mitochondria are depolarized using 10 μm of the uncoupler CCCP, FL PINK1 accumulates in the mitochondrial fraction, accompanied by a decrease in the levels of processed ΔMTS and ΔN1 PINK1. However, a strong increase of a higher molecular weight form of PINK1 is observed specifically in the mitochondrial fraction (Fig. 1B). This represents phosphorylated full-length (P-FL) PINK1 (20, 27).

FIGURE 1.

Phosphorylated PINK1 is present at the outer mitochondrial membrane. A, schematic representing FL PINK1, including the kinase domain and MTS. MPP cleaves off the MTS, resulting in ΔMTS PINK1, and further processing by PARL at residue 103 results in the ΔN1 PINK1 product. The four phosphorylation sites analyzed in this study (blue) and the sites mutated in KI (green) PINK1 are indicated. B, HEK cells transiently transfected with WT or KI FLAG-tagged human PINK1 and treated with 10 μm CCCP for 3 h were fractionated in postnuclear or homogenate fraction (H), and subsequent H fraction was further centrifuged at 7000 × g to obtain the mitochondrially depleted or cytosol-enriched (C) and mitochondrially enriched (M) fractions, respectively. Expression of PINK1 was evaluated after SDS-PAGE on 7.5% Tris acetate gel and immunoblotted using anti-FLAGM2. Immunoblotting for the mitochondrial marker HSP60 served as a fractionation quality control. For WT, but not KI, a doublet was observed that corresponded to the phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated FL form of PINK1 (P-FL and FL, respectively). Further processed PINK1 forms are indicated as ΔMTS, ΔN1, and ΔN2. WB, Western blot. C, mitochondrially enriched fractions, obtained from HEK cells transfected with WT and KI PINK1-FLAG and incubated with 10 μm CCCP for 3 h, were treated with LPP at 30 °C. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE on a 7.5% Tris acetate gel and 7.5% Phos-Tag gel and immunoblotted with anti-FLAGM2 antibody for PINK1 detection. A control for loss of phosphorylation by 30 °C incubation alone was included. Phosphatase treatment confirmed that the upper band (P-FL) was a phosphorylated form of PINK1. D, fractionation of HEK cells treated for 3 h with either 10 μm CCCP or 10 μm lactacystin was analyzed by SDS-PAGE on a 7.5% Tris acetate or 7.5% Phos-Tag gel and further immunoblotted for PINK1 detection using anti-FLAGM2 antibody. Mitochondrial PINK1 was phosphorylated under control (DMSO) conditions but accumulated upon CCCP-induced depolarization. Proteasomal blockage with lactacystin also led to a modest increase of P-FL PINK1 in addition to accumulation of the ΔN1 processed form. E, mitochondrially enriched fractions of MEF cells stably expressing FL PINK1-FLAG were subjected to a PK sensitivity assay to assess submitochondrial localization of P-FL PINK1. P-FL is PK-sensitive, whereas non-phosphorylated FL PINK1 and PINK1 lacking the mitochondrial targeting sequence (ΔMTS) are at least partially protected from PK even under hypotonic conditions (2 mm HEPES). As a control for protein digestion under each condition, fractions were also immunoblotted using antibodies against the outer membrane protein TOM20, intermembrane space protein HtrA2, and matrix protein HSP60. F, MEFs derived from PARL WT and PARL KO mice stably expressing WT PINK1-V5 were fractionated and expression of PINK1 was evaluated after SDS-PAGE and anti-V5 immunoblotting. ΔMTS PINK1 accumulates in PARL KO cells and further N-terminal processing is altered leading to an accumulation of PINK1 C-terminal fragments in the mitochondria (M) of PARL KO cells. G, mitochondrially enriched fractions from PARL WT and KO MEFs stably expressing WT PINK1-V5 were subjected to PK treatment under isotonic and hypotonic (20 mm and 2 mm HEPES) conditions in the presence or absence of detergent. Equal amounts were loaded for PARL WT and KO. A higher exposure inset for PARL WT allows better analysis of PINK1 expression under these conditions. ΔMTS PINK1 was cleaved by PARL and accumulated in PARL KO mitochondria but was only digested by PK in the presence of detergent. Depolarization induced by CCCP led to the accumulation of P-FL PINK1, sensitive to proteinase K under isotonic conditions. Therefore, the accumulation caused by the absence of PARL or by CCCP-induced depolarization concerns different PINK1 forms present in different submitochondrial compartments. As a control, the PK sensitivity of the outer membrane protein TOM20, intermembrane space protein HtrA2, and matrix protein HSP60 was evaluated by immunoblotting.

Dephosphorylation of mitochondrial lysate from CCCP-treated cells with LPP confirms that this PINK1 form is phosphatase-sensitive (Fig. 1C, top panel). Moreover, when we separate the same samples on a Phos-Tag gel in which negatively charged phosphorylated proteins migrate more slowly because of their interaction with the Mn2+-Phos-TagTM complex conjugated with the polyacrylamide gel, we strongly increase the resolution between phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated FL PINK1 (Fig. 1C, bottom panel). The altered migration pattern on the Phos-Tag gel and the clear decrease in intensity of the phosphorylated versus the non-phosphorylated PINK1 upon LPP treatment suggest that, despite the detection of residual LPP-insensitive PINK1, the higher molecular weight band represents phosphorylated PINK1.

KI PINK1, catalytically inactivated by two mutations, K219A and D362A in the ATP-binding pocket and catalytic core, respectively (25), is also enriched in the mitochondrial fraction upon depolarization using CCCP (Fig. 1B, KI PINK1). However, no phosphorylated PINK1 is detected, indicating that the observed phosphorylation event is dependent on PINK1 kinase activity (Fig. 1, B and C, KI PINK1).

Although CCCP treatment leads to a strong accumulation of this phosphorylated form of PINK1, we nevertheless detected low amounts of phosphorylated PINK1 in control conditions, especially when enriching for mitochondria (Fig. 1, B, sixth lane, and D, third lane). This suggests that the increased intensity of the phosphorylated band after CCCP treatment reflects the general accumulation of PINK1 as a consequence of the decreased import of PINK1 into the mitochondria under those conditions and not necessarily induction of phosphorylation per se. Indeed, when we blocked the rapid degradation of processed PINK1 by treating cells with the proteasomal inhibitor lactacystin, we not only observed a robust accumulation of ΔN1 PINK1, known to be degraded in a proteasome-dependent manner (41), but we also saw a modest increase in phosphorylated FL PINK1 (Fig. 1D). Via Phos-Tag gels we obtained a better resolution of the phosphorylated PINK1 (Fig. 1D, bottom panel). The detection of phosphorylated PINK1 under DMSO control and lactacystin treatment conditions confirms that PINK1 phosphorylation occurs in the absence of CCCP treatment.

To verify that phosphorylated PINK1 is located at the mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM), we used a PK sensitivity assay (35). We isolated mitochondria from PINK1 KO MEFs rescued by stable PINK1-FLAG expression. First we added PK to purified mitochondria in isotonic buffer, which led to digestion of proteins at the outer leaflet of the MOM. Under these conditions, phosphorylated FL PINK1 is indeed accessible and degraded by PK, as is the MOM-associated protein TOM20 (Fig. 1E). Digestion in hypotonic 2 mm HEPES buffer, which caused the rupture of the MOM by osmotic shock, made all proteins from the intermembrane space, the inner leaflet of the MOM, and, finally, the outer leaflet of the mitochondrial inner membrane accessible to PK but preserved the remaining mitoplast, consisting of the matrix and mitochondrial inner membrane. Although intermembrane space-localized HtrA2 was degraded under these conditions, no further digestion of PINK1 was observed, indicating that the residual pool of PINK1 was associated with the mitoplast. This was confirmed in the third step of the experiment, where all membranes were solubilized using detergent, and addition of PK resulted in full degradation of all PINK1 protein forms and the matrix protein HSP60 (Fig. 1E). We therefore conclude that phosphorylated PINK1 is mainly localized at the MOM, whereas non-phosphorylated FL PINK1 is partially protected inside the mitoplast.

The PARL protease, located in the mitochondrial inner membrane, is implicated in the processing of PINK1 (37–40). Stable expression of C-terminal V5-tagged PINK1 in WT and PARL KO MEFs shows the specific accumulation of ΔMTS PINK1 in the absence of PARL (Fig. 1F), confirming that MPP-processed PINK1 and not FL PINK1 is the substrate for PARL cleavage (38). We also find an altered pattern of further processed C-terminal PINK1 fragments (Fig. 1F, processed forms). We reasoned that studying PINK1 under basal and depolarizing conditions in PARL KO cells, where we observed much higher levels of ΔMTS PINK1, could unequivocally confirm the submitochondrial localization of this PINK1 form in the intermembrane space and matrix.

When we examined PK susceptibility in mitochondrial fractions obtained from PARL KO MEFs, we observed high levels of ΔMTS PINK1 in the presence of PK under both isotonic and hypotonic conditions (Fig. 1G). Only when detergent was added and proteins localized inside the mitoplast became accessible to PK was ΔMTS PINK1 degraded. These results demonstrate unambiguously that ΔMTS PINK1 is indeed protected in the mitoplast. Moreover, CCCP treatment in PARL KO cells led to the accumulation of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated FL PINK1 at the MOM, which is sensitive to PK, while, at the same time, a reduction in the amount of accumulated ΔMTS was observed under these conditions, indicating that transport of PINK1 into the matrix was blocked (Fig. 1G, right panel).

On the basis of these results, we propose that FL PINK1 is phosphorylated at the outer mitochondrial membrane prior to mitochondrial import and processing by MPP and PARL. This phosphorylation event is independent of mitochondrial membrane depolarization induced by CCCP, but, as a consequence of import blockage, phosphorylated PINK1 accumulates on depolarized mitochondria.

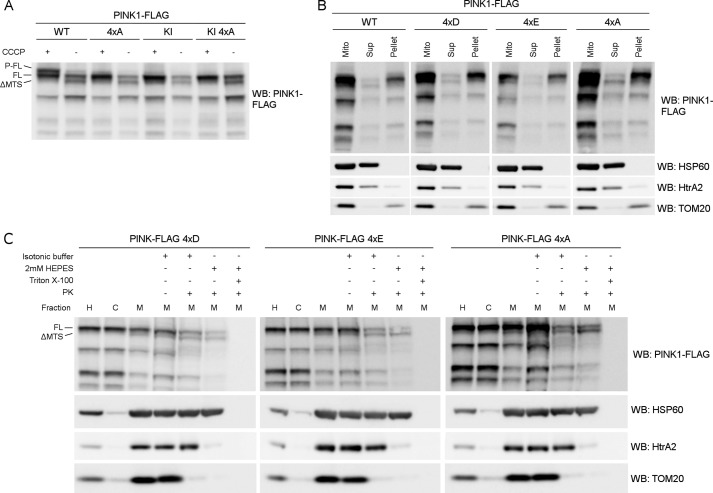

The Putative PINK1 Phosphorylation Sites Are Not Involved in Its Mitochondrial Processing or Localization

PINK1 has been reported to be phosphorylated on at least four different residues: Ser-228, Thr-257, Thr-313, and Ser-402 (20, 27, 29). To verify the role of these residues, we made a 4×A quadruple mutant PINK1 construct in which all four sites are mutated to an alanine, and we assessed the accumulation of phosphorylated PINK1 under CCCP-induced depolarization conditions. The 4×A quadruple mutant PINK1 was processed by MPP to ΔMTS PINK1 under basal conditions, and FL 4×A PINK1 accumulated upon CCCP treatment. It is also clear that phosphorylation of this phosphomutant is affected when compared with WT PINK1 (Fig. 2A), confirming that at least one of these four sites is important for the phosphorylation of PINK1 to occur. Furthermore, it follows that phosphorylation at none of these four residues is required for accumulation of PINK1 upon mitochondrial depolarization.

FIGURE 2.

Mutation of Ser-228, Thr-257, Thr-313, and Ser-402 affects phosphorylation without interfering with localization or processing. A, mitochondrially enriched fractions of DMSO (control) or 10 μm CCCP-treated HEK cells transiently expressing WT and KI PINK1-FLAG WT with and without the quadruple mutation of the putative phosphorylation sites Ser-228, Thr-257, Thr-313, and Ser-402 (4×A) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting against anti-FLAGM2 for PINK1 detection. Results show that P-FL PINK1 no longer accumulates for 4×A quadruple mutant PINK1. WB, Western blot. B, mitochondrially enriched fractions from MEF cells stably expressing WT, phosphomimetic (4×D and 4×E) or phosphodead (4×A) quadruple PINK1-FLAG mutants were treated with Na2CO3 (pH 11.5). The majority of PINK1 was not extracted by Na2CO3 indicating that the WT and the quadruple mutants are membrane-associated proteins. Expression of soluble HSP60 and HtrA2 and membrane-associated TOM20 was evaluated as a control for Na2CO3 extraction. Mito, mitochondria; Sup, supernatant. C, Proteinase K sensitivity was tested on mitochondrially enriched fractions from MEF cells stably expressing either 4×D, 4×E, and 4×A quadruple mutant PINK1-FLAG. The distribution of FL and processed PINK1 forms was not altered because the pattern for mitochondrial fractions and PK sensitivity under isotonic and hypotonic (2 mm HEPES) conditions was unchanged. H, post-nuclear or homogenate fraction; C, mitochondria-depleted or cytosolic fraction; M, mitochondria-enriched fraction. As a control for protein digestion under each condition, the PK sensitivity of the outer membrane protein TOM20, intermembrane space protein HtrA2, and matrix protein HSP60 was evaluated. H, post-nuclear or homogenate fraction; C, mitochondria-depleted or cytosolic fraction; M, mitochondria-enriched fraction.

To exclude that the observed effect on PINK1 phosphorylation is due to mislocalization of the quadruple mutant PINK1, we analyzed its mitochondrial and submitochondrial localization and processing using two different complementing techniques. We first treated purified mitochondria with Na2CO3 at pH 11.5 to determine the membrane association of the different forms of PINK1. The Na2CO3 treatment converts closed vesicles to open membrane sheets, releasing content proteins and peripheral membrane proteins (34). We observed that the majority of PINK1, including the phosphorylated form of PINK1, was resistant to this treatment and followed the pattern of the membrane-associated protein TOM20 (Fig. 2B, WT). In contrast, the soluble matrix protein HSP60 and intermembrane space-located HtrA2 are extracted. Therefore, PINK1 remains strongly associated with the mitochondrial membrane. Interestingly, not only the 4×A mutant, but also quadruple mutant PINK1 harboring phosphomimetic mutations to aspartic acid (4×D) and glutamic acid (4×E), phenocopy the PINK1 wild-type form upon Na2CO3 treatment (Fig. 2B).

To further distinguish between inner and outer membrane-associated proteins, we performed a PK susceptibility assay. For both phosphomimetic 4×D and 4×E, and for phosphodead 4×A mutant PINK1, we observed PK susceptibility patterns that were comparable with the pattern obtained for WT PINK1 (Fig. 2C).

The fact that quadruple PINK1 mutants show no changes in Na2CO3 extraction or PK digestion pattern indicates that loss of phosphorylation of the 4×A phosphodead mutant is not due to mislocalization or misprocessing of PINK1 and, furthermore, that phosphorylation of PINK1 does not affect its mitochondrial transport and insertion.

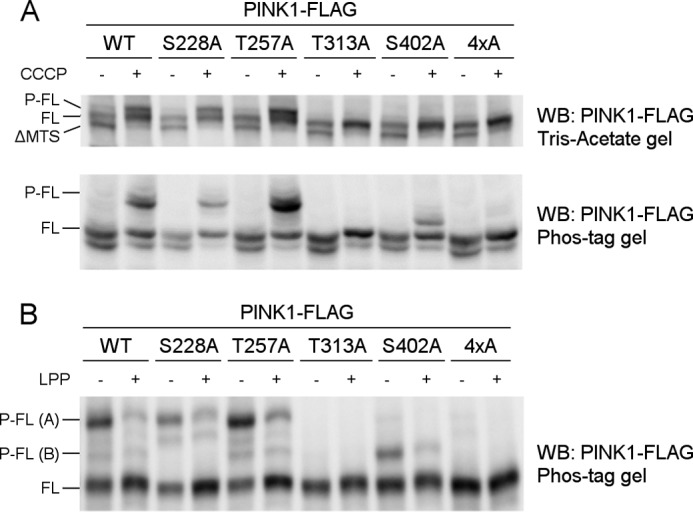

Threonine 313 and Serine 402 Are Required for PINK1 Phosphorylation

To evaluate which of the four residues under investigation are responsible for the observed effect on PINK1 phosphorylation, we mutated Ser-228, Thr-257, Thr-313, and Ser-402 individually to alanine and evaluated the effect on PINK1 phosphorylation in a cell-based approach, using CCCP-induced depolarization to trigger accumulation of phosphorylated PINK1. Mutation of Ser-228 or Thr-257 does not affect the phosphorylation of PINK1 because both mutant forms present a migration profile identical to that of wild-type PINK1 in Tris acetate or Phos-Tag gel (Fig. 3A). Mutation of residue Thr-313 or Ser-402 appears to abolish the P-FL PINK1 band (Fig. 3A, top panel), indicating that both T313A and S402A interfere with PINK1 phosphorylation.

FIGURE 3.

Thr-313 and Ser-402 are required for PINK1 phosphorylation at the mitochondrial outer membrane. A, mitochondrially enriched fractions from HEK cells transiently transfected with different phosphomutant forms of PINK1-FLAG and treated with DMSO or 10 μm CCCP were analyzed by SDS-PAGE on 7.5% Tris acetate and 7.5% Phos-Tag gels. The presence of P-FL, FL, and ΔMTS PINK1 was assessed by immunoblotting using anti-FLAGM2 antibody. Although FL PINK1 accumulated upon CCCP treatment for every evaluated mutant, P-FL PINK1 was not detected or altered for T313A, S402A, and the 4×A quadruple mutant PINK1. WB, Western blot. B, mitochondrial fractions from CCCP-treated HEK cells transfected with different phosphomutant PINK1-FLAG forms were treated with LPP and further probed with anti-FLAGM2 antibody for PINK1 detection. The bands P-FL(A) and P-FL(B) show sensitivity to LPP, indicating that they are both phosphorylated forms of PINK1 (P-FL A and B).

However, when phosphorylation of these mutants was analyzed in a Phos-Tag gel, a slower migrating band was still detected for the S402A mutant (Fig. 3A, bottom panel). This band is LPP-sensitive (Fig. 3B, P-FL (B)), indicating that there is residual phosphorylation occurring on S402A-mutated PINK1. The identification of two different phosphorylated PINK1 forms points to the occurrence of multiphosphorylation of PINK1, which involves several residues. Although mutation of Thr-313 fully abrogates all PINK1 phosphorylation, at least one phosphosite is not affected by S402A mutation, which results in the detection of residually phosphorylated P-FL (B) PINK1.

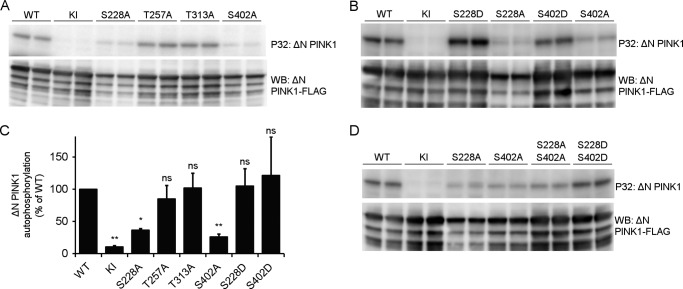

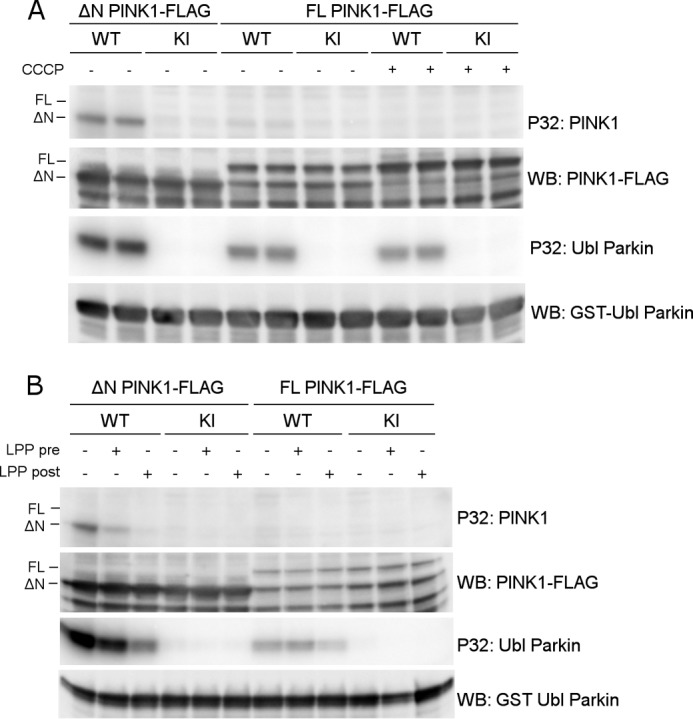

Full-length PINK1 Is Active but Is Not Autophosphorylated in Vitro

To investigate whether the phosphorylation we observed in our cell-based approach is the result of autophosphorylation activity by PINK1, we set up an in vitro kinase assay with radiolabeled ATP using purified human PINK1. We expressed both FL human PINK1 and an N-terminally truncated PINK1 form that lacks the first 112 N-terminal amino acids before the kinase domain (from here on referred to as ΔN PINK1) in COS cells.

Although ΔN PINK1 showed autophosphorylation activity, this was not observed for FL PINK1 (Fig. 4A, P32: PINK1). Importantly, purified FL PINK1 is catalytically active because it is able to phosphorylate the Ubiquitin-like (Ubl) domain of Parkin (Fig. 4A, P32: Ubl Parkin) (20). This phosphorylation activity is specific because it is not observed for purified KI PINK1. CCCP-induced depolarization of COS cells prior to PINK1 purification has no effect on autophosphorylation or substrate phosphorylation (Fig. 4A, CCCP). Contrary to previous reports (20, 27) we show that depolarization is not required for PINK1 activity or autophosphorylation.

FIGURE 4.

Full-length PINK1 shows lack of autophosphorylation activity in vitro. A, an in vitro phosphorylation assay using [γ-32P]ATP was performed with purified WT and KI PINK1-FLAG and purified GST-Ubl Parkin as substrate. Although WT ΔN PINK1 shows autophosphorylation and is able to phosphorylate the substrate Parkin, the autoradiogram shows no detectable autophosphorylation for FL PINK1, although FL PINK1 phosphorylates the Ubl-domain of Parkin. WB, Western blot. B, PINK1 was dephosphorylated using LPP prior (pre) to incubation with [γ-32P]ATP and Ubl Parkin in an in vitro phosphorylation. This dephosphorylation did not reveal an increase in detectable FL PINK1 autophosphorylation. The same LPP treatment of PINK1 and Parkin after (post) completion of the kinase assay did lead to a considerable amount of Parkin and ΔN PINK1 dephosphorylation, indicating that protein dephosphorylation was successful under the applied conditions.

We considered the possibility that perhaps FL PINK1 was already phosphorylated prior to purification and that dephosphorylation of the purified kinase was needed so that in vitro radioactive phosphor incorporation could be assessed. Therefore, we treated both ΔN and FL PINK1 with LPP immediately after purification and subsequently washed away the phosphatase before incubating the purified kinase with radiolabeled ATP. However, pretreatment of FL PINK1 with LPP did not lead to the detection of autophosphorylation activity (Fig. 4B, P32: PINK1). Therefore, the lack of in vitro autophosphorylation activity of FL PINK1 is not due to prior phosphorylation and occupancy of the sites by non-radioactive phosphates. As a control, ΔN PINK1 autophosphorylation and Ubl Parkin phosphorylation were still detected after LPP pretreatment, confirming successful removal of the phosphatase before performing the kinase assay (Fig. 4B, P32: Ubl Parkin). Addition of LPP after incubation of kinase and substrate in the presence of radiolabeled ATP led to a reduction in phosphorylated Parkin and autophosphorylated ΔN PINK1, which confirms that LPP is active under these experimental conditions.

The absence of detectable in vitro autophosphorylation of FL PINK1 suggests that the N-terminal region has an inhibitory effect on the autophosphorylation activity of PINK1 under our experimental conditions. Because we observe phosphorylation of Ubl-Parkin, we conclude that non-phosphorylated PINK1 is able to phosphorylate its substrate, although we cannot exclude that the efficiency is lower. Therefore, autophosphorylation is not required for substrate phosphorylation.

Truncated Human PINK1 Is Autophosphorylated at Residues Ser-228 and Ser-402

To further investigate PINK1 autophosphorylation, we analyzed the kinase activity of purified ΔN PINK1 in more depth using PINK1 phosphomutants at the four candidate residues. ΔN KI PINK1 no longer showed autophosphorylation, validating the specificity of our in vitro assay for human ΔN PINK1 autophosphorylation (Fig. 4A). Remarkably, mutation of residue Ser-228 interfered with ΔN PINK1 autophosphorylation because the incorporation of radiolabeled ATP was reduced significantly, reaching only 36% of ΔN WT PINK1 autophosphorylation levels (Fig. 5, A and C). Mutation of residues Thr-257 and, intriguingly, Thr-313 to alanine did not affect ΔN PINK1 autophosphorylation, indicating that these residues are not involved in the in vitro autophosphorylation of ΔN PINK1. Finally, S402A mutation resulted in a marked inhibition of in vitro ΔN PINK1 autophosphorylation by 75% (Fig. 5, A and B).

FIGURE 5.

Autophosphorylation of ΔN PINK1 occurs at residues Ser-228 and Ser-402. A, an in vitro phosphorylation assay using [γ-32P]ATP was performed with purified human ΔN PINK1 harboring phosphodead mutations on four putative phosphosites. The phosphomutants S228A and S402A showed reduced phosphorylation, whereas mutation of Thr-257 and Thr-313 did not affect ΔN PINK1 autophosphorylation when compared with WT. B, in vitro phosphorylation assay using [γ-32P]ATP and purified ΔN PINK1 with phosphomimetic and phosphodead mutant PINK1 for residues Ser-228 and Ser-402 shows that a phosphomimetic mutant PINK1 can restore PINK1 phosphorylation levels observed for the corresponding phosphodead mutation. C, quantification of ΔN PINK1 autophosphorylation relative to WT (mean ± S.E., n = 3 independent experiments). Statistical significance was calculated between each mutant and WT ΔN PINK1 using Dunnett's test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ns, nonspecific. D, in vitro phosphorylation assay using [γ-32P]ATP and purified ΔN PINK1 with a combined S228A and S402A mutation shows decreased ΔN PINK1 autophosphorylation levels comparable with the levels for the single mutations, indicating the existence of residual phosphorylated residue(s) on PINK1. The combined phosphomimetic mutation S228D and S402D shows increased in vitro autophosphorylation levels, showing that phosphorylation of these two residues increases PINK1 kinase activity and phosphorylation of the residual phosphoresidue(s). Immunoblot analysis using anti-FLAGM2 shows that equal amounts of PINK1 were applied.

Although the separate mutations of S228A and S402A both lower ΔN PINK1 autophosphorylation, they do not lead to a complete inhibition. To scrutinize the interplay between these two sites, we constructed phosphomimetic mutants of ΔN PINK1 at either the Ser-228 or the Ser-402 site by mutating the serine to an aspartic acid residue. ΔN PINK1 autophosphorylation was fully restored for both S228D and S402D PINK1 despite the fact that, in both cases, one candidate phosphosite was blocked by a mutation (Fig. 5, B and C). This confirms that both the Ser-228 and Ser-402 residues regulate PINK1 kinase activity. The fact that single alanine mutation of each site largely abolishes autophosphorylation suggests that both sites need to be phosphorylated to make ΔN PINK1 fully active. Finally, residual autophosphorylation activity of ΔN PINK1 was observed in the double S228A/S402A mutant, indicating that at least one other residue in PINK1 is autophosphorylated apart from these two sites (and besides Thr-257 and Thr-313). Double mutation of Ser-228 and Ser-402 to aspartic acid confirms the increased activity of PINK1 upon phosphorylation and the existence of additional phosphorylation site(s) (Fig. 5D).

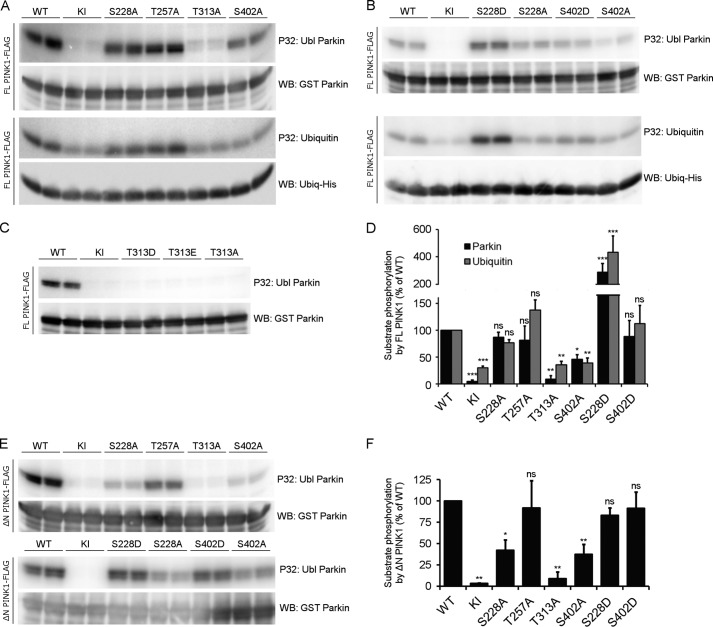

Phosphorylation of PINK1 Residues Ser-228 and Ser-402 Can Regulate Substrate Phosphorylation

To understand how each of the different putative phosphosites can influence substrate phosphorylation, we incubated mutated FL PINK1 with Parkin. We found that neither Ser-228 nor Thr-257 mutation affected Parkin phosphorylation in the context of FL PINK1. Mutation of Thr-313, in contrast, completely abrogated the phosphorylation of Parkin. The effects of S402A were less severe, but, nevertheless, substrate phosphorylation was reduced by more than 50% (Fig. 6A, top panel). We next investigated whether phosphorylation of Ubiquitin, another PINK1 substrate, is affected in a similar way. Despite the fact that a residual phosphorylation, most likely by a contaminating kinase, was detected with KI PINK1 in this assay, we observed that Ser-228 and Thr-257 mutants of FL PINK1 did not affect Ubiquitin phosphorylation. As is the case for Parkin, both Thr-313 and Ser-402 are important because Ubiquitin phosphorylation is reduced by more than 60% when either of these two residues is mutated (Fig. 6A, bottom panel).

FIGURE 6.

The residues Thr-313 and Ser-402 are important for substrate phosphorylation. A, an in vitro phosphorylation assay using [γ-32P]ATP was performed on purified FL PINK1 with purified Ubl Parkin or His-tagged Ubiquitin. Autoradiographic exposure shows that, for FL PINK1, mutation of Ser-228 and Thr-257 does not affect Parkin or Ubiquitin phosphorylation. Mutation of Thr-313 completely abrogates substrate phosphorylation, whereas the S402A mutation leads to a substantial decrease. There is still phosphorylation detectable for KI PINK1, indicating the presence of a contaminating kinase capable of phosphorylating Ubiquitin at low levels. Immunoblot analysis using anti-GST or anti-His confirms that equal amounts of Parkin and Ubiquitin were applied. WB, Western blot. B, an in vitro phosphorylation assay using [γ-32P]ATP, FL PINK1, and Ubl Parkin or Ubiquitin shows that the S228D and S402D mutations increase substrate phosphorylation. The S228D mutation increases substrate phosphorylation beyond WT levels, which are comparable with that obtained for S228A PINK1. The decreased Parkin phosphorylation for FL S402A PINK1 can be rescued by a phosphomimetic mutation, S402D. C, an in vitro phosphorylation assay using [γ-32P]ATP was performed on purified FL PINK1 mutated at the Thr-313 residue with purified Ubl Parkin. Phosphomimetic (T313D or T313E) mutation of Thr-313 does not rescue the decrease in Parkin phosphorylation observed for T313A. D, quantification of Ubl Parkin and Ubiquitin phosphorylation relative to WT. Statistical significance was calculated between each mutant and WT FL PINK1 using Dunnett's test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ns, nonspecific. Data are mean ± S.E. (n = 3 independent experiments). E, an in vitro phosphorylation assay using [γ-32P]ATP was performed using purified ΔN PINK1 and purified Ubl Parkin. Similar to FL PINK1, Parkin phosphorylation is abolished upon T313A mutation in ΔN PINK1, whereas the S228A and S402A mutations reduce it significantly. The S228D and S402D phosphomimetic mutations restore Parkin phosphorylation back to WT levels. F, quantification of Ubl Parkin phosphorylation by ΔN PINK1. Statistical significance was calculated between each mutant and WT ΔN PINK1 using Dunnett's test. *, p < 0.05; **, p <0.01; ns, nonspecific. Data are mean ± S.E. (n = 3 independent experiments).

We next evaluated the role of Ser-228 and Ser-402 phosphorylation on substrate phosphorylation by introducing phosphomimetic mutations at these sites. Interestingly, both phosphomimetic mutations, S228D and S402D, are able to increase substrate phosphorylation (Fig. 6B). Although neither Parkin nor Ubiquitin phosphorylation are reduced significantly for S228A PINK1, introduction of a phosphomimetic mutation at this residue results in a 3- and 4-fold increase of Parkin and Ubiquitin phosphorylation, respectively. S402D mutation restores Parkin and Ubiquitin phosphorylation levels to those of WT PINK1 (Fig. 6D). Therefore, phosphorylation at both Ser-228 and Ser-402 residues regulates substrate phosphorylation.

Our results studying ΔN PINK1 autophosphorylation indicated already that Thr-313 is not an autophosphorylation site (Fig. 5B). Nevertheless, mutation of this residue drastically affects Parkin phosphorylation by PINK1 (Fig. 6A), and, importantly, mutation of this residue also leads to the complete absence of PINK1 phosphorylation in cells (Fig. 3A). To investigate the role of this residue on the kinase activity of FL PINK1, we evaluated the effect of an aspartic acid (T313D) or glutamic acid (T313E) phosphomimetic residue at this position. The Thr-313 phosphomimetic mutant PINK1 forms are unable to phosphorylate Parkin (Fig. 6C), behaving the same as the phosphodead alanine counterpart mutant. Taken together, these results indicate that, although the Thr-313 residue is relevant for substrate phosphorylation, it is not regulated through phosphorylation.

Because of the different outcomes of the mutations of the candidate phosphosites with regard to in vitro autophosphorylation and PINK1 phosphorylation observed in cells, we decided to analyze the role of all four residues for Parkin phosphorylation in the context of ΔN PINK1 as well. Although the effects of Thr-257, Thr-313, and Ser-402 mutation are similar to those observed for FL PINK1, it is of particular interest that Parkin phosphorylation is decreased significantly by more than 50% for ΔN PINK1 harboring the S228A mutation (Fig. 6, E and F). Because we showed that phosphomimetic mutation of both S228D and S402D restores ΔN PINK1 autophosphorylation levels to WT levels, we proceeded to check their effect on Parkin phosphorylation. As expected, both mutations increased Parkin phosphorylation. However, in contrast to our results with FL PINK1 (Fig. 6B), ΔN PINK1 S228D and S402D both restored Parkin phosphorylation levels to those of WT ΔN PINK1 (Fig. 6, E and F).

In sum, we show that both Ubiquitin and Parkin are directly phosphorylated by human FL PINK1. Phosphorylation of the Ser-228 and Ser-402 residues can regulate the phosphorylation of both substrates, but their individual contribution depends on the context because Ser-228 phosphorylation only occurs for WT PINK1 when the N terminus of PINK1 is deleted. Although Thr-313 is required for substrate phosphorylation, it does not regulate PINK1 activity through phosphorylation.

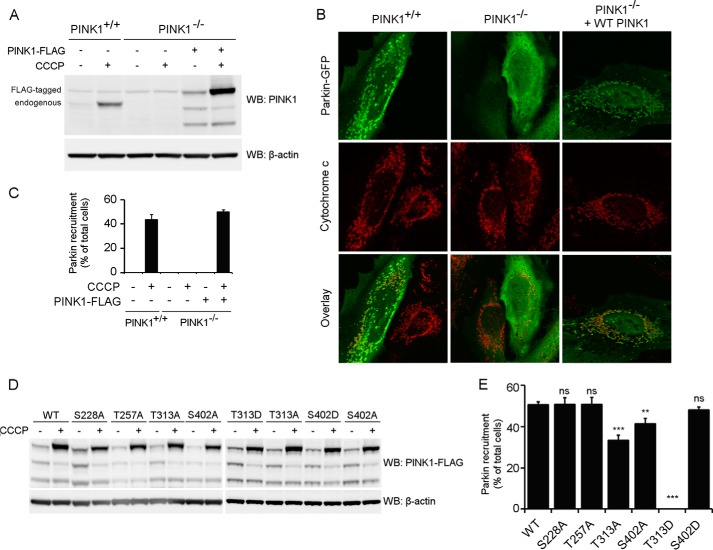

The Thr-313 and Ser-402 Residues Are Important for Parkin Recruitment

It is well established that PINK1 and Parkin cooperate to flag defective mitochondria for mitophagic removal. When PINK1 accumulates on the outer membrane of depolarized mitochondria, it recruits Parkin from the cytosol. However, previous reports indicate that, besides PINK1 accumulation, PINK1 also needs to be activated by phosphorylation (20, 27, 28). Therefore, we decided to investigate the implication of each of the four putative phosphosites in Parkin recruitment.

We created PINK1 KO HeLa cells using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/Cas technology (33). In these cells, absence of PINK1 expression leads to lack of Parkin recruitment to depolarized mitochondria (Fig. 7, A–C). Transient transfection of PINK1 in these PINK1 KO HeLa cells leads to near endogenous PINK1 expression levels under the pMSCV LTR promoter and accumulation upon CCCP-induced depolarization (Fig. 7A). Note that although a doublet can clearly be observed on Tris acetate gels, the accumulated PINK1 band does not resolve as a doublet on a conventional BisTris gel.

FIGURE 7.

Thr-313 and Ser-402 are important for Parkin recruitment by PINK1. A, WT (PINK1+/+) and PINK1 KO (PINK1−/−) HeLa cells were treated with 10 μm CCCP for 3 h and analyzed for PINK1 expression via Western blot (WB) analysis. No endogenous PINK1 was detected in PINK1−/− cells. B, HeLa cells were transfected with Parkin-GFP and treated with CCCP for 3 h. Immunohistochemistry for Parkin-GFP (green) and the mitochondrial marker cytochrome c (red) shows that WT (PINK1+/+) but not PINK1 KO (PINK1−/−) HeLa cells display mitochondrial Parkin recruitment. Expression of WT PINK1 in PINK1 KO cells rescues Parkin recruitment. Immunoblot analysis using anti-β-actin shows equal loading. C, quantification of Parkin recruitment in WT (PINK1+/+), KO (PINK1−/−), and KO HeLa cells rescued with human WT PINK1 after 3 h of DMSO or 10 μm CCCP treatment. Statistical significance was calculated between HeLa WT and PINK1 KO rescued cells using Student's t test. Data are mean ± S.E. (n = 6 independent experiments). D, PINK1 KO HeLa cells were transiently transfected with WT and mutant PINK1 and subsequently treated with DMSO or 10 μm CCCP for 3 h. PINK1 expression levels were analyzed by Western blot analysis. Immunoblot analysis using anti-β-actin shows equal loading. E, quantification of Parkin recruitment in PINK1 KO HeLa cells rescued with human WT or mutant PINK1 after 3 h of 10 μm CCCP treatment. Statistical significance was calculated between each mutant and WT PINK1 using Dunnett's test. **, p <0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ns, nonspecific. Data are mean ± S.E. (n = 4 independent experiments).

Reintroducing WT PINK1 in PINK1 KO HeLa cells rescues Parkin recruitment, confirming that the mitophagy defects we observed are caused by lack of PINK1 expression (Fig. 7, B and C). When we expressed the PINK1 mutants S228A or T257A in our PINK1 KO HeLa cell line, we observed a rescue of Parkin recruitment upon CCCP treatment to the same extent as for WT PINK1. However, Thr-313 or Ser-402 mutation results in a reduction of Parkin recruitment of 30 and 20% respectively (Fig. 7, D and E). Interestingly, when we tried to rescue the defect in Parkin recruitment using the phosphomimetic constructs T313D and S402D PINK1, we found that expression of T313D PINK1 did not rescue Parkin recruitment at all, whereas S402D PINK1 was able to restore Parkin recruitment to WT levels (Fig. 7, D and E, T313D and S402D).

Our findings identify that PINK1 residue Thr-313 is not only crucial for PINK1 and substrate phosphorylation in vitro, it also affects Parkin recruitment in cells. Additionally, the phosphorylation event of residue Ser-402 is required for PINK1 to be fully active. We found no role for Ser-228 phosphorylation in regulating FL PINK1 function in cells.

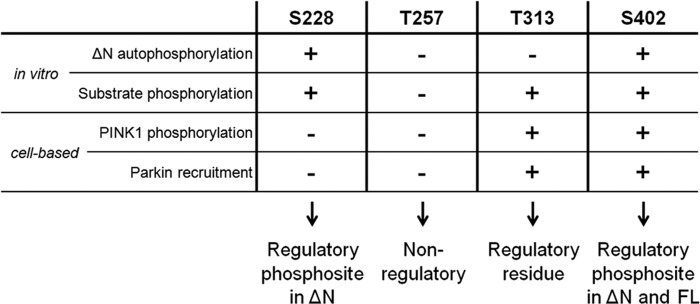

DISCUSSION

We show the first evidence that both Parkin and Ubiquitin phosphorylation can be regulated by PINK1 phosphorylation on residues Ser-228 and Ser-402. Additionally, we reveal that, although the residue Thr-313 is not required for autophosphorylation, it is essential for substrate phosphorylation and Parkin recruitment.

We used a systematic approach evaluating the role of four reported PINK1 phosphosites, as depicted in Fig. 8. No changes in autophosphorylation, substrate phosphorylation, or Parkin recruitment were observed upon Thr-257 mutation, which indicates that its phosphorylation is not required for PINK1 kinase activity.

FIGURE 8.

Overview of the role of Ser-228, Thr-257, Thr-313, and Ser-402 residues in PINK1. Ser-228 is an autophosphorylation site in ΔN PINK1, and it can regulate substrate phosphorylation in vitro. However, both in vitro and in cells, Ser-228 phosphorylation plays no role in the regulation of WT FL PINK1 activity. Nevertheless, we propose it as a regulatory phosphosite for processed PINK1. We found no implication for Thr-257 as a (regulatory) phosphosite in any of our experimental setups and, therefore, propose that this putative phosphosite has no functional role for PINK1 activity. Although Thr-313 is an essential residue for PINK1, its function is not regulated through phosphorylation because autophosphorylation is not affected upon Thr-313 mutation, and phosphomimetics rescue none of the observed functional defects. Like Ser-228, Ser-402 is an autophosphorylation site in ΔN PINK1, but it also regulates FL PINK1 in vitro and in cells. We propose this residue as a regulatory phosphosite for both FL and processed PINK1.

Interestingly, mutation of Thr-313 fully abrogated FL PINK1 phosphorylation at the mitochondria (Fig. 3A) and also severely affected Parkin and Ubiquitin phosphorylation in vitro (Fig. 6, A and E), as well as Parkin recruitment (Fig. 7E). These observations, and the fact that T313M is a known PD-associated polymorphism (42), underscore the importance of this residue for PINK1 function. However, autophosphorylation of ΔN PINK1 was not altered by Thr-313 mutation (Fig. 5A), indicating that catalytic activity is unaffected. Therefore, Thr-313 is not a regulatory phosphorylation site but, rather, a structurally important amino acid possibly involved in substrate binding. Thr-313 has been reported to be phosphorylated in a truncated PINK1 form by MARK2 (29). In light of our results, we suggest that further studies are required to elucidate the mechanism by which MARK2 and PINK1 interact to influence each other's function and activity.

We provide in vitro evidence showing that Ser-228 and Ser-402 are true PINK1 autophosphorylation sites (Fig. 5) and that both are capable of regulating PINK1 kinase activity and substrate phosphorylation (Figs. 5C and 6, B and E). Phosphorylation of the Ser-228 residue is of special interest because its involvement in PINK1 regulation differs for ΔN and FL PINK1 (Figs. 6 and 8). Our cell-based assays reveal no alteration of PINK1 phosphorylation or of Parkin recruitment for S228A PINK1 (Figs. 3A and 7, E and F), and refine the role of Ser-228 as a regulatory phosphosite in processed but not in FL PINK1.

The majority of PINK1 in vitro kinase activity studies have focused on truncated forms of PINK1 (25, 26, 36, 43, 44) or, alternatively, used insect orthologues displaying a higher catalytic activity compared with human PINK1 (45). However, the phosphorylation discrepancies we observed between FL and ΔN PINK1 call for a careful interpretation when studying different PINK1 forms. Indeed, our results suggest that PINK1 catalytic activity is regulated by the N-terminal region (Fig. 4).

The fact that the T313A mutation does not affect ΔN PINK1 autophosphorylation in vitro (Fig. 5A) but clearly abrogates FL PINK1 phosphorylation in cells (Fig. 3A) indicates that the latter is unlikely to be a direct autophosphorylation event. However, because it is dependent on PINK1 kinase activity and intermolecular phosphorylation (28), we propose that Thr-313 could be required for the binding of other essential interaction partners.

Although the majority of PINK1 studies underscore the importance of CCCP-induced depolarization (20–22, 27, 28, 46), we find PINK1 phosphorylation in the absence of depolarization (Fig. 1). Although depolarization leads to a rapid accumulation of phosphorylated PINK1 at the outer membrane (Fig. 1E), our data show that it is not required for PINK activation.

The distinct localization of phosphorylated PINK1 at the MOM indicates that PINK1 phosphorylation is important for the initiation of mitophagy. Recently, several models have proposed that PINK1-mediated phosphorylation of Parkin and Ubiquitin regulates mitochondrial relocalization and ubiquitination (21–23, 47). We find that the PINK1 mutants T313A and S402A not only affect Parkin and Ubiquitin phosphorylation but also result in reduced Parkin recruitment (Fig. 7E). Phosphomimetic PINK1 S402D, which restores Parkin phosphorylation in vitro (Fig. 6D), is able to rescue Parkin recruitment (Fig. 7E), suggesting that Parkin phosphorylation is required but not essential for its recruitment to depolarized mitochondria.

In sum, this study uncovers some of the mechanisms by which PINK1 kinase activity is regulated. Although numerous examples illustrate that protein phosphorylation can alter the stability, dynamics, and binding of proteins (48), this is seldom an on-off process. Multisite phosphorylation allows for signal integration and fine-tuning, regulating the ultimate biological effect of kinases. The interplay of Ser-228 and Ser-402 for PINK1 autophosphorylation in vitro indeed indicates that phosphorylation of one site stimulates phosphorylation of the other (Fig. 5C). One could postulate that, besides the role of Ser402 in the regulation of mitophagy, additional unidentified phosphorylation sites and other posttranslational modifications could be required to regulate PINK1 function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Dr. Monique Beullens for sharing expertise on protein phosphorylation and Dr. Nicholas T. Hertz for advice and technical insights on PINK1 purification. We also thank Prof. Dr. Miratul M. K. Muqit for TcPINK1 plasmids, which helped during the early stages of this research; Dr. Sven Vilain, Dr. Lutgarde Serneels, and Gert Vanmarcke for advice and technical assistance in the generation of a PINK1 KO HeLa cell line; Sam Lismont for guidance on protein purification; and Prof. Dr. Kris Gevaert and his team for advice on mass spectrometric analysis of phosphorylated proteins.

This work was supported by the Flemish agency for Innovation by Science and Technology (IWT), by the Fund for Scientific Research Flanders (FWO), by Research Fund KU Leuven, by the Hercules Foundation, by Federal Office for Scientific Affairs Grant IAP P7/16, by a Methusalem grant of the Flemish government, and by the Flemish Institute for Biotechnology. B. D. S. is a paid consultant for the Alzheimer disease research programs at Janssen Pharmaceutica, Envivo, and Remynd NV.

- PD

- Parkinson disease

- CCCP

- carbonyl cyanide m-cholorophenylhydrazone

- KI

- kinase-inactive

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- PK

- proteinase K

- LPP

- λ protein phosphatase

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- FL

- full-length

- MPP

- mitochondrial processing peptidase

- MTS

- mitochondrial targeting sequence

- P-FL

- phosphorylated full-length

- MOM

- mitochondrial outer membrane

- PARL

- Presenilin-associated rhomboid-like protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nuytemans K., Theuns J., Cruts M., Van Broeckhoven C. (2010) Genetic etiology of Parkinson disease associated with mutations in the SNCA, PARK2, PINK1, PARK7, and LRRK2 genes: a mutation update. Hum. Mutat. 31, 763–780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Valente E. M., Abou-Sleiman P. M., Caputo V., Muqit M. M., Harvey K., Gispert S., Ali Z., Del Turco D., Bentivoglio A. R., Healy D. G., Albanese A., Nussbaum R., González-Maldonado R., Deller T., Salvi S., Cortelli P., Gilks W. P., Latchman D. S., Harvey R. J., Dallapiccola B., Auburger G., Wood N. W. (2004) Hereditary early-onset Parkinson's disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science 304, 1158–1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yang Y., Gehrke S., Imai Y., Huang Z., Ouyang Y., Wang J.-W., Yang L., Beal M. F., Vogel H., Lu B. (2006) Mitochondrial pathology and muscle and dopaminergic neuron degeneration caused by inactivation of Drosophila Pink1 is rescued by Parkin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 10793–10798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Exner N., Treske B., Paquet D., Holmström K., Schiesling C., Gispert S., Carballo-Carbajal I., Berg D., Hoepken H.-H., Gasser T., Krüger R., Winklhofer K. F., Vogel F., Reichert A. S., Auburger G., Kahle P. J., Schmid B., Haass C. (2007) Loss-of-function of human PINK1 results in mitochondrial pathology and can be rescued by parkin. J. Neurosci. 27, 12413–12418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clark I. E., Dodson M. W., Jiang C., Cao J. H., Huh J. R., Seol J. H., Yoo S. J., Hay B. A., Guo M. (2006) Drosophila pink1 is required for mitochondrial function and interacts genetically with parkin. Nature 441, 1162–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wood-Kaczmar A., Gandhi S., Yao Z., Abramov A. Y., Abramov A. S., Miljan E. A., Keen G., Stanyer L., Hargreaves I., Klupsch K., Deas E., Downward J., Mansfield L., Jat P., Taylor J., Heales S., Duchen M. R., Latchman D., Tabrizi S. J., Wood N. W. (2008) PINK1 is necessary for long term survival and mitochondrial function in human dopaminergic neurons. PloS ONE 3, e2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Plun-Favreau H., Klupsch K., Moisoi N., Gandhi S., Kjaer S., Frith D., Harvey K., Deas E., Harvey R. J., McDonald N., Wood N. W., Martins L. M., Downward J. (2007) The mitochondrial protease HtrA2 is regulated by Parkinson's disease-associated kinase PINK1. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 1243–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pridgeon J. W., Olzmann J. A., Chin L.-S., Li L. (2007) PINK1 protects against oxidative stress by phosphorylating mitochondrial chaperone TRAP1. PLoS Biol. 5, e172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morais V. A., Verstreken P., Roethig A., Smet J., Snellinx A., Vanbrabant M., Haddad D., Frezza C., Mandemakers W., Vogt-Weisenhorn D., Van Coster R., Wurst W., Scorrano L., De Strooper B. (2009) Parkinson's disease mutations in PINK1 result in decreased Complex I activity and deficient synaptic function. EMBO Mol. Med. 1, 99–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gautier C. A., Kitada T., Shen J. (2008) Loss of PINK1 causes mitochondrial functional defects and increased sensitivity to oxidative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 11364–11369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morais V. A., Haddad D., Craessaerts K., De Bock P.-J., Swerts J., Vilain S., Aerts L., Overbergh L., Grünewald A., Seibler P., Klein C., Gevaert K., Verstreken P., De Strooper B. (2014) PINK1 loss of function mutations affect mitochondrial complex I activity via NdufA10 ubiquinone uncoupling. Science 344, 203–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pogson J. H., Ivatt R. M., Sanchez-Martinez A., Tufi R., Wilson E., Mortiboys H., Whitworth A. J. (2014) The complex I subunit NDUFA10 selectively rescues Drosophila pink1 mutants through a mechanism independent of mitophagy. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weihofen A., Thomas K. J., Ostaszewski B. L., Cookson M. R., Selkoe D. J. (2009) Pink1 forms a multiprotein complex with Miro and Milton, linking Pink1 function to mitochondrial trafficking. Biochemistry 48, 2045–2052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang X., Winter D., Ashrafi G., Schlehe J., Wong Y. L., Selkoe D., Rice S., Steen J., LaVoie M. J., Schwarz T. L. (2011) PINK1 and Parkin target Miro for phosphorylation and degradation to arrest mitochondrial motility. Cell 147, 893–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deng H., Dodson M. W., Huang H., Guo M. (2008) The Parkinson's disease genes pink1 and parkin promote mitochondrial fission and/or inhibit fusion in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 14503–14508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lutz A. K., Exner N., Fett M. E., Schlehe J. S., Kloos K., Lämmermann K., Brunner B., Kurz-Drexler A., Vogel F., Reichert A. S., Bouman L., Vogt-Weisenhorn D., Wurst W., Tatzelt J., Haass C., Winklhofer K. F. (2009) Loss of parkin or PINK1 function increases Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fragmentation. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 22938–22951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Poole A. C., Thomas R. E., Andrews L. A., McBride H. M., Whitworth A. J., Pallanck L. J. (2008) The PINK1/Parkin pathway regulates mitochondrial morphology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 1638–1643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Narendra D. P., Jin S. M., Tanaka A., Suen D. F., Gautier C. A., Shen J., Cookson M. R., Youle R. J. (2010) PINK1 is selectively stabilized on impaired mitochondria to activate Parkin. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Youle R. J., Narendra D. P. (2011) Mechanisms of mitophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 9–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kondapalli C., Kazlauskaite A., Zhang N., Woodroof H. I., Campbell D. G., Gourlay R., Burchell L., Walden H., Macartney T. J., Deak M., Knebel A., Alessi D. R., Muqit M. M. (2012) PINK1 is activated by mitochondrial membrane potential depolarization and stimulates Parkin E3 ligase activity by phosphorylating serine 65. Open Biol. 2, 120080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kane L. A., Lazarou M., Fogel A. I., Li Y., Yamano K., Sarraf S. A., Banerjee S., Youle R. J. (2014) PINK1 phosphorylates ubiquitin to activate Parkin E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. J. Cell Biol. 205, 143–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kazlauskaite A., Kondapalli C., Gourlay R., Campbell D. G., Ritorto M. S., Hofmann K., Alessi D. R., Knebel A., Trost M., Muqit M. M. (2014) Parkin is activated by PINK1-dependent phosphorylation of ubiquitin at Serine 65. Biochem. J. 460, 127–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koyano F., Okatsu K., Kosako H., Tamura Y., Go E., Kimura M., Kimura Y., Tsuchiya H., Yoshihara H., Hirokawa T., Endo T., Fon E. A., Trempe J.-F., Saeki Y., Tanaka K., Matsuda N. (2014) Ubiquitin is phosphorylated by PINK1 to activate parkin. Nature 510, 162–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen Y., Dorn G. W. (2013) PINK1-phosphorylated Mitofusin 2 is a parkin receptor for culling damaged mitochondria. Science 340, 471–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Beilina A., Van Der Brug M., Ahmad R., Kesavapany S., Miller D. W., Petsko G. A., Cookson M. R. (2005) Mutations in PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 associated with recessive parkinsonism have differential effects on protein stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 5703–5708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sim C. H., Lio D. S., Mok S. S., Masters C. L., Hill A. F., Culvenor J. G., Cheng H.-C. (2006) C-terminal truncation and Parkinson's disease-associated mutations down-regulate the protein serine/threonine kinase activity of PTEN-induced kinase-1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15, 3251–3262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Okatsu K., Oka T., Iguchi M., Imamura K., Kosako H., Tani N., Kimura M., Go E., Koyano F., Funayama M., Shiba-Fukushima K., Sato S., Shimizu H., Fukunaga Y., Taniguchi H., Komatsu M., Hattori N., Mihara K., Tanaka K., Matsuda N. (2012) PINK1 autophosphorylation upon membrane potential dissipation is essential for Parkin recruitment to damaged mitochondria. Nat. Commun. 3, 1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Okatsu K., Uno M., Koyano F., Go E., Kimura M., Oka T., Tanaka K., Matsuda N. (2013) A dimeric PINK1-containing complex on depolarized mitochondria stimulates Parkin recruitment. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 36372–36384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Matenia D., Hempp C., Timm T., Eikhof A., Mandelkow E.-M. (2012) MARK2 turns on PINK1 at Thr-313, a mutation site in Parkinson disease: effects on mitochondrial transport. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 8174–8186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Matenia D., Mandelkow E. M. (2014) Emerging modes of PINK1 signaling: another task for MARK2. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 7, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matta S., Van Kolen K., da Cunha R., van den Bogaart G., Mandemakers W., Miskiewicz K., De Bock P.-J., Morais V. A., Vilain S., Haddad D., Delbroek L., Swerts J., Chávez-Gutiérrez L., Esposito G., Daneels G., Karran E., Holt M., Gevaert K., Moechars D. W., De Strooper B., Verstreken P. (2012) LRRK2 controls an EndoA phosphorylation cycle in synaptic endocytosis. Neuron 75, 1008–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cipolat S., Rudka T., Hartmann D., Costa V., Serneels L., Craessaerts K., Metzger K., Frezza C., Annaert W., D'Adamio L., Derks C., Dejaegere T., Pellegrini L., D'Hooge R., Scorrano L., De Strooper B. (2006) Mitochondrial rhomboid PARL regulates cytochrome c release during apoptosis via OPA1-dependent cristae remodeling. Cell 126, 163–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cong L., Ran F. A., Cox D., Lin S., Barretto R., Habib N., Hsu P. D., Wu X., Jiang W., Marraffini L. A., Zhang F. (2013) Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fujiki Y., Hubbard A. L., Fowler S., Lazarow P. B. (1982) Isolation of intracellular membranes by means of sodium carbonate treatment: application to endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 93, 97–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dimmer K. S., Navoni F., Casarin A., Trevisson E., Endele S., Winterpacht A., Salviati L., Scorrano L. (2008) LETM1, deleted in Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome is required for normal mitochondrial morphology and cellular viability. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 201–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hertz N. T., Berthet A., Sos M. L., Thorn K. S., Burlingame A. L., Nakamura K., Shokat K. M. (2013) A Neo-substrate that amplifies catalytic activity of Parkinson's-disease-related kinase PINK1. Cell 154, 737–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jin S. M., Lazarou M., Wang C., Kane L. A., Narendra D. P., Youle R. J. (2010) Mitochondrial membrane potential regulates PINK1 import and proteolytic destabilization by PARL. J. Cell Biol. 191, 933–942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Greene A. W., Grenier K., Aguileta M. A., Muise S., Farazifard R., Haque M. E., McBride H. M., Park D. S., Fon E. A. (2012) Mitochondrial processing peptidase regulates PINK1 processing, import and Parkin recruitment. EMBO Rep. 13, 378–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Deas E., Plun-Favreau H., Gandhi S., Desmond H., Kjaer S., Loh S. H., Renton A. E., Harvey R. J., Whitworth A. J., Martins L. M., Abramov A. Y., Wood N. W. (2011) PINK1 cleavage at position A103 by the mitochondrial protease PARL. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 867–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Meissner C., Lorenz H., Weihofen A., Selkoe D. J., Lemberg M. K. (2011) The mitochondrial intramembrane protease PARL cleaves human Pink1 to regulate Pink1 trafficking. J. Neurochem. 117, 856–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yamano K., Youle R. J. (2013) PINK1 is degraded through the N-end rule pathway. Autophagy 9, 1758–1769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Luo Q., Yang X., Yao Y., Li H., Wang Y. (2014) T313M polymorphism of the PINK1 gene in Parkinson's disease. Exp. Ther. Med. 8, 286–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim Y., Park J., Kim S., Song S., Kwon S.-K., Lee S.-H., Kitada T., Kim J.-M., Chung J. (2008) PINK1 controls mitochondrial localization of Parkin through direct phosphorylation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 377, 975–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Silvestri L., Caputo V., Belacchio E., Atorino L., Dallapiccola B., Valente E. M., Casari G. (2005) Mitochondrial import and enzymatic activity of PINK1 mutants associated to recessive parkinsonism. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 3477–3492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Woodroof H. I., Pogson J. H., Begley M., Cantley L. C., Deak M., Campbell D. G., van Aalten D. M., Whitworth A. J., Alessi D. R., Muqit M. M. (2011) Discovery of catalytically active orthologues of the Parkinson's disease kinase PINK1: analysis of substrate specificity and impact of mutations. Open Biol. 1, 110012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Iguchi M., Kujuro Y., Okatsu K., Koyano F., Kosako H., Kimura M., Suzuki N., Uchiyama S., Tanaka K., Matsuda N. (2013) Parkin catalyzed ubiquitin-ester transfer is triggered by PINK1-dependent phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 22019–22032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ordureau A., Sarraf S. A., Duda D. M., Heo J.-M., Jedrychowski M. P., Sviderskiy V. O., Olszewski J. L., Koerber J. T., Xie T., Beausoleil S. A., Wells J. A., Gygi S. P., Schulman B. A., Harper J. W. (2014) Quantitative proteomics reveal a feedforward mechanism for mitochondrial PARKIN translocation and ubiquitin chain synthesis. Mol. Cell 56, 360–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nishi H., Shaytan A., Panchenko A. R. (2014) Physicochemical mechanisms of protein regulation by phosphorylation. Front. Genet. 5, 270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]