Background: The biological function of insertion/deletion sequences associated with AMD has not been fully characterized.

Results: The HTRA1 regulatory region contains an insertion/deletion sequence that is significantly up-regulated in retinal neuronal cell lines.

Conclusion: HTRA1 expression is enhanced by a mutation in the insertion/deletion in the HTRA1 regulatory region.

Significance: This is the characterization of the HTRA1 regulatory elements and the effect of insertion/deletion sequences associated with AMD.

Keywords: DNA-binding Protein, Photoreceptor, Retina, Retinal Degeneration, Transcription Regulation, ARMS2, EMSA, HTRA1, Age-related Macular Degeneration

Abstract

Dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD) accounts for over 85% of AMD cases in the United States, whereas Japanese AMD patients predominantly progress to wet AMD or polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Recent genome-wide association studies have revealed a strong association between AMD and an insertion/deletion sequence between the ARMS2 (age-related maculopathy susceptibility 2) and HTRA1 (high temperature requirement A serine peptidase 1) genes. Transcription regulator activity was localized in mouse retinas using heterozygous HtrA1 knock-out mice in which HtrA1 exon 1 was replaced with β-galactosidase cDNA, thereby resulting in dominant expression of the photoreceptors. The insertion/deletion sequence significantly induced HTRA1 transcription regulator activity in photoreceptor cell lines but not in retinal pigmented epithelium or other cell types. A deletion construct of the HTRA1 regulatory region indicated that potential transcriptional suppressors and activators surround the insertion/deletion sequence. Ten double-stranded DNA probes for this region were designed, three of which interacted with nuclear extracts from 661W cells in EMSA. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) of these EMSA bands subsequently identified a protein that bound the insertion/deletion sequence, LYRIC (lysine-rich CEACAM1 co-isolated) protein. In addition, induced pluripotent stem cells from wet AMD patients carrying the insertion/deletion sequence showed significant up-regulation of the HTRA1 transcript compared with controls. These data suggest that the insertion/deletion sequence alters the suppressor and activator cis-elements of HTRA1 and triggers sustained up-regulation of HTRA1. These results are consistent with a transgenic mouse model that ubiquitously overexpresses HtrA1 and exhibits characteristics similar to those of wet AMD patients.

Introduction

Recent genome-wide association studies have identified more than 19 susceptibility genes associated with age-related macular degeneration (AMD)2 (1). Among these genes, two loci have been highly associated with AMD, and these include the CFH (complement factor H) gene on chromosome 1q32 and the ARMS2/HTRA1 (age-related macular degeneration susceptibility 2/high temperature requirement A1) gene on chromosome 10q26. Although a strong association of CFH Y402H (rs1061170) with Caucasians with dry AMD has been established (2, 3), this locus has not been associated with the majority of Japanese patients with wet AMD (4). Rather, ARMS2/HTRA1 is the region most strongly associated with wet AMD in Japanese patients (5, 6). Moreover, the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), rs10490924, was shown in a single linkage disequilibrium (LD) block to increase the risk of wet AMD in both Caucasian and Japanese AMD populations (6). This LD block included the entire ARMS2 gene and a portion of HTRA1 exon 1 (Fig. 1). However, genome-wide association studies alone are insufficient to distinguish between these two candidate genes. Previous reports have identified an insertion/deletion region ∼443 bp in length that immediately follows the second exon of ARMS2 within the regulatory element of HTRA1 (7, 8). This finding led to confusion as to whether a single gene or both ARMS2 and HTRA1 are involved in AMD. ARMS2 is a recent gene evolutionarily and is within the primate lineage (7, 9). Its protein product, ARMS2, has been shown to localize to the mitochondria of the inner segment of the photoreceptor (7) and to interact with fibulin-6 in the extracellular matrix of the choroid (10). However, details regarding the biological function(s) of ARMS2 remain unclear (7, 9, 10). In contrast, HTRA1 has been characterized to some extent. HTRA1 belongs to the HTRA serine protease family, which is highly conserved from microorganisms to multicellular organisms, including humans (11). Several cellular and molecular studies have suggested that HTRA1 plays a key role in regulating various cellular processes via the cleavage and/or binding of pivotal factors that participate in cell proliferation, migration, and cell fate (12–15). Recently, up-regulation of human HTRA1 expression in the mouse retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) was shown to induce a branching network of choroidal vessels and polypoidal lesions and severe degeneration of the elastic lamina and tunica media of the choroidal vessels, similar to that observed in AMD and PCV patients (16, 17). A mutation in HTRA1 has also been associated with a hereditary form of familial cerebral small vessel disease (CARASIL (cerebral autosomal recessive arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy)) (18). The original report by Dewan et al. (19) described the up-regulation of HTRA1 in fibroblasts obtained from AMD patients. This result was both confirmed and denied by several other groups and was also subjected to a regulatory element characterization assay containing the insertion/deletion sequence (7, 8). However, the results obtained were based on transcription regulator activity that was measured using the human RPE cell line, ARPE19. On the basis of previous study, the purpose of this study is to characterize transcription regulation of ARMS2 and HTRA1 genes in wet form AMD.

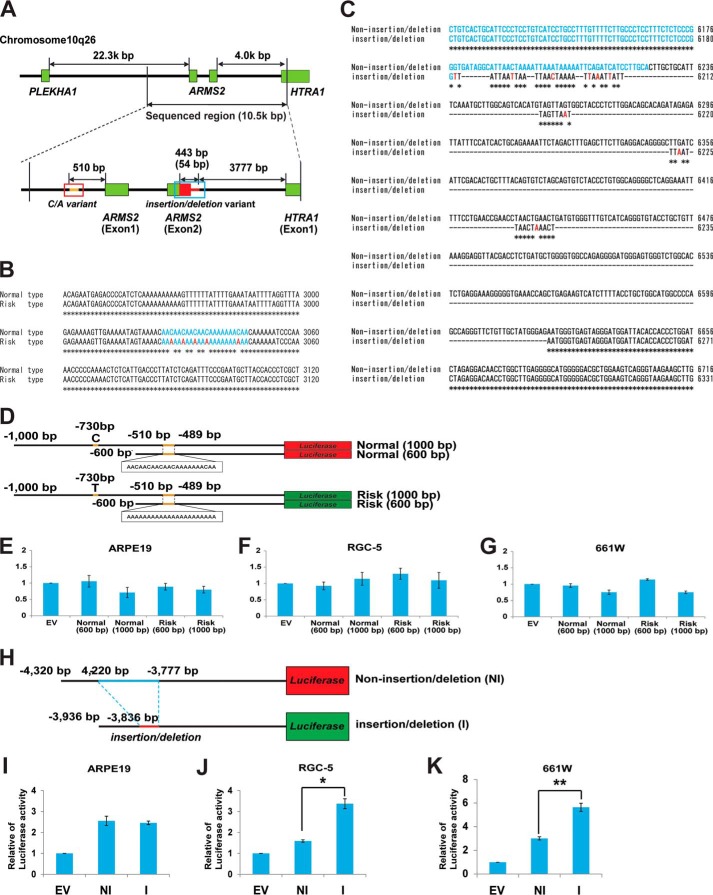

FIGURE 1.

Transcription regulatory region of ARMS2 and HTRA1. A, a schematic diagram of the transcription regulatory region of ARMS2 and HTRA1. Sequencing of the indicated transcription regulatory region spanned 10.5 kbp and was performed for both AMD and non-AMD controls. Two unique sequences, a C/A repeat variant in the ARMS2 transcription regulator (indicated with a blue box) and an insertion/deletion variant downstream of exon 2 of ARMS2 (indicated with a red box), were identified in a patient with AMD that carried the SNP, rs10490924. B, characteristic C/A mutations present in the ARMS2 transcription regulatory region (blue, C/A variant; red, C to A substitution). C, the insertion/deletion mutations present in the HTRA1 transcription regulatory region (blue, ARMS2 exon 2 region; red, point mutations). D–G, analysis of ARMS2 transcription regulator activity using a luciferase assay system. D, four luciferase vectors were generated to analyze ARMS2 transcription regulator activity: normal (1,000 bp), normal (600 bp), risk (1,000 bp), and risk (600 bp). The 1,000-bp sequence contained a C/T SNP in the upper 730-bp region from ARMS2 exon 1. ARMS2 transcription regulator activity detected in ARPE19 cells (E), RGC-5 cells (F), and 661W cells (G). Error bars, S.D. H–K, HTRA1 transcription regulator activity detected in various retinal cell lines. H, schematic diagram of the ARMS2-HTRA1 constructs used in the luciferase assays performed (black line, common regulator sequence; blue line, non-insertion/deletion regulator unique sequence; red line, insertion/deletion regulator unique sequence). Full-length HTRA1 transcription regulator activity detected in ARPE19 cells (I), RGC5 cells (*, p = 7.5 × 10−6) (J), and 661W cells (**, p = 1.07 × 10−6) (K). Error bars, S.D. EV, empty vector; NI, non-insertion/deletion regulator; I, insertion/deletion regulator.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Subjects

A total of 226 Japanese patients with typical wet AMD without PCV (average age, 74.68 ± 8.86 years) were classified as 5b according to Seddon et al. (20). In addition, 228 non-AMD Japanese individuals (average age, 75.22 ± 7.23 years) were recruited as controls for this study (Table 1). All patients were diagnosed by fundus observation or by fluorescein/indocyanine green angiographic findings. For the controls, no signs of early AMD, such as soft drusen or alterations of the retinal pigment epithelium in the macula area, were observed ophthalmoscopically. Informed consent was obtained from all of the patients and controls, and the procedures performed conformed to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for sequencing

| Primer name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| PLEKHA1-ARMS2-F1 | CCCCATGCTTTCAGGGTTCACC |

| PLEKHA1-ARMS2-R1 | GGGGTCTCATTCTGTTGTCCAGGC |

| PLEKHA1-ARMS2-F2 | TGTTCCCAGCCTCTCCCCACTCTT |

| PLEKHA1-ARMS2-R2 | GAACCACTTCTCCCAGCCAAACACT |

| PLEKHA1-ARMS2-F3 | GTTCAGTGGCGCAATCTCGGC |

| PLEKHA1-ARMS2-R3 | CCTCATGCACTGCTAGTGGGATTGT |

| PLEKHA1-ARMS2-F4 | CAGGCTGGAGTGCAATGGTGTGAT |

| PLEKHA1-ARMS2-R4 | GGAGGATTGCTTGAGCCCAGGAC |

| PLEKHA1-ARMS2-F5 | CTACGTGGCGGGCGCTGTCT |

| PLEKHA1-ARMS2-R5 | CTGTGTTGGCTGGACTCGGTAGCT |

| ARMS2-F1 | CTGAGCCGAGGAGTATGAGG |

| ARMS2-R1 | CAGGAACCACCGAGGAGGACAGAC |

| ARMS2-F2 | TCCCTGAGACCACCCAACAA |

| ARMS2-R2 | CGCGCTCACATTTAGAACAT |

| ARMS2-F3 | GCGCTTTGTGCTTGCCATAGT |

| ARMS2-R3 | CCAAAATAGGACAAAGGTGAGG |

| ARMS2-F4 | GTGAAACCCCATCTCTACTAAAAATACAG |

| ARMS2-R4 | CCCACATCAGTTCAGTTAGGTTCGGTTCAG |

| ARMS2-F5 | GCTTGGCAGTCACATGTAGTTAGT |

| ARMS2-R5 | CAGGCCTTGGCACGGTATTCT |

| ARMS2-HTRA1-F2 | CAAGGCCTGGTGAGTGAGAAATGAGTT |

| ARMS2-HTRA1-R2 | GAGGGGGTGGAGAATGGGTAAGAGG |

| ARMS2-HTRA1-F3 | TCCACTTCGGCCGACACTTCCTC |

| ARMS2-HTRA1-R3 | TGCCTTTCTTTGCCCACATCTCC |

| ARMS2-HTRA1-F4 | TGGGGGCACGAGGATGGAAGAG |

| ARMS2-HTRA1-R4 | AGGGAATGAGCGGACCGAAAACAGT |

| ARMS2-HTRA1-F5 | TGGGCAAAGAAAGGCACAGAGACC |

| ARMS2-HTRA1-R5 | TGGGGCAGATGGAATTAAAAGGACA |

| ARMS2-HTRA1-F6 | CCGCAAAGCAGTGGGGAAGTT |

| ARMS2-HTRA1-R6 | CCTCATCCCGAACCCTCAAACCTC |

| ARMS2-HTRA1-F7 | TTGAGGGGGCTTATAGGTATTTGGAGTT |

| ARMS2-HTRA1-R7 | GGGTGGCATGCGTGTCCGTATTC |

| ARMS2-HTRA1-F8 | CCCAACGGATGCACCAAAGATTC |

| ARMS2-HTRA1-R8 | CCCGGTCACGCGCTGGTTCT |

| ARMS2-HTRA1-F9 | ACGCATGCCACCCACAACAACTTTT |

| ARMS2-HTRA1-R9 | GCGGGATCTGCATGGCGACTCT |

DNA Isolation and Sequencing

Human DNA was extracted from blood samples using a Magtration System 8Lx (Precision System Science Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The PLEKHA1-ARMS2-HTRA1 region of genomic DNA was amplified from both control and AMD patient samples using the primers listed in Table 1. PCR amplifications for all primer sets were performed in a 20-μl volume containing 100 ng of genomic DNA and 1 unit of Taq polymerase (PrimerStar, Takara Bio Co. Ltd., Japan) for 35–40 cycles of amplification. Amplified PCR products were then purified using an ExoSAP-IT kit (GE Healthcare) and were sequenced using a BigDye Terminator version 3.1 sequencing kit (Invitrogen) and an ABI 3130 Genetic Analyzer.

Cell Culture

The mouse photoreceptor cell line, 661W, and the rat retinal ganglion cell line, RGC5, were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. The human RPE cell line, ARPE19, was cultured in DMEM/F-12 containing 15% FBS at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

Transcription Regulator Activity Assay

The ARMS2 regulatory region and the HTRA1 regulatory region were amplified and cloned into the pGL4.10 (Luc2) luciferase vector (Promega, WI) (Table 2). Insertion/deletion variants were also constructed using a KOD mutagenesis kit (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). For the luciferase assays performed, 661W cells, RGC5 cells, and ARPE19 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (1 × 104 cells/well) 24 h before transfection. Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine LTX with Plus reagent (Invitrogen). A firefly luciferase gene was integrated into a reporter vector to normalize the activity of both transcription regulators. Luciferase activity was detected using the Dual-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega) and a microplate reader (Plate Chameleon, Hidex, Turku, Finland).

TABLE 2.

Primer used for cloning

| Number | Oligonucleotide sequencea | Forward/Reverse | Enzyme site | Description | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ACGTCTCGAGGCCTCGCAGCGGTGACGAG | Reverse | XhoI | Reverse primer | Normal, in/del |

| 2 | ACGTGAGCTCAGATGCAGCCCAATCTTCTCCTAACA | Forward | SacI | Normal or in/del: full-length | Normal, in/del |

| 3 | ACGTGAGCTCCCCTCCTTTCTCTCCCGGGTG | Forward | SacI | Normal or in/del: Δ82 | Normal, in/del |

| 4 | ACGTGAGCTCTGTCTAGCAGTGTCTACCCTGTGGCA | Forward | SacI | Normal: Δ298 | Normal |

| 5 | ACGTGAGCTCGGTGTACCTGCTGTTAAAGGAGGT | Forward | SacI | Normal: Δ384 | Normal |

| 6 | ACGTGAGCTCAATGGGTGAGTAGGGATGGATTACA | Forward | SacI | Normal: Δ543 | Normal |

| 7 | ACGTGAGCTCAATGGGTGAGTAGGGATGGATTA | Forward | SacI | In/del: Δ148 | In/del |

| 8 | AATGGGTGAGTAGGGATGGATTACACC | Inverse-F | In/del: Δin/del-F | In/del | |

| 9 | CCGGGAGAGAAAGGAGGGCAA | Inverse-R | In/del: Δin/del-R | In/del |

a Boldface sequence, restriction enzyme site for cloning.

Preparation of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) from Controls and AMD Patients

Human iPSCs were established by infecting circulating T cells obtained from the peripheral blood of human AMD patients with the Sendai virus as described previously (21, 22). Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained from donors by the centrifugation of heparinized blood over a Ficoll-Paque PREMIUM (GE Healthcare) gradient, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The peripheral blood mononuclear cells were then cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2 with plate-bound anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies (BD Pharmingen) in GT-T502 medium (Kohjin Bio, Sakado, Japan) supplemented with recombinant interleukin-2 (IL-2) at 175 Japan reference units/ml. After 5 days, activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells were collected and transferred to 6-well plates (1.5 × 106 cells/well) coated with anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies, and the cells were incubated for an additional 24 h. A solution containing Sendai virus vectors that individually carried OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (DNAVEC Inc., Japan) was added to each well. At 24 h postinfection, the medium was changed to fresh CT-T502 medium. At 48 h postinfection, the cells were collected and transferred to a 10-cm dish that contained mitomycin C-inactivated mouse embryonic fibroblast feeder cells (6 × 104 to 6 × 105 cells/dish). After an additional 24 h of incubation, the medium was changed to iPSC medium, which consisted of DMEM/F-12 medium (Sigma) supplemented with 20% knock-out serum replacement (Invitrogen), 1 mm l-glutamine, 1 mm non-essential amino acids, 0.1 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 50 units of penicillin, 50 mg/ml streptomycin, and 4 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan). The iPSC medium was changed every other day until colonies were picked. The generated iPSCs were maintained on irradiated mouse embryonic fibroblast feeder cells in iPSC medium. Culture medium for the iPSCs was changed every 2 days, and the cells were passaged using 1 mg/ml collagenase IV every 5–6 days.

EMSA

Nuclear extracts were prepared with a CelLytic nuclear extraction kit (Sigma), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The nuclear protein concentration of each sample was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific).

EMSA probes were 40 bp in length and are listed in Table 3. Probes 1–3 were designed to cover non-insertion/deletion and insertion/deletion regions (non-insertion/deletion, bp −4320 to −4220; insertion/deletion, bp −3936 to −3836). Probes 4–8 were designed to cover the non-insertion/deletion regulatory region (non-insertion/deletion, bp −3936 to −3777). Probes 9 and 10 were designed to cover the insertion/deletion region (insertion/deletion, −3836 to −3782 bp). Double-stranded DNA probes were biotin-labeled using a LightShift chemiluminescent EMSA kit (Thermo Scientific) and then were mixed with nuclear extracts. After 20 min, the samples were subjected to electrophoresis on 7% EMSA gels. After electrophoresis, the samples were transferred onto Biodyne B precut modified nylon membranes (Thermo Scientific). The membranes were cross-linked in a UV transilluminator for 15 min and then were incubated with blocking buffer and streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugates. Bound conjugates were detected using a molecular imager (ChemiDoc XRS+, Bio-Rad).

TABLE 3.

EMSA probe sequence

| Number | Type | Probe sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sense | AGATGCAGCCCAATCTTCTCCTAACATCTGGATTCCTCTC |

| Antisense | GAGAGGAATCCAGATGTTAGGAGAAGATTGGGCTGCATCT | |

| 2 | Sense | GATTCCTCTCTGTCACTGCATTCCCTCCTGTCATCCTGCC |

| Antisense | GGCAGGATGACAGGAGGGAATGCAGTGACAGAGAGGAATC | |

| 3 | Sense | TCATCCTGCCTTTGTTTTCTTGCCCTCCTTTCTCTCCCGG |

| Antisense | CCGGGAGAGAAAGGAGGGCAAGAAAACAAAGGCAGGATGA | |

| 4 | Sense | GGTGTACCTGCTGTTAAAGGAGGTTACGACCTCTGATGCT |

| Antisense | AGCATCAGAGGTCGTAACCTCCTTTAACAGCAGGTACACC | |

| 5 | Sense | ATGCTGGGGTGGCCAGAGGGGATGGGAGTGGGTCTGGCAC |

| Antisense | GTGCCAGACCCACTCCCATCCCCTCTGGCCACCCCAGCAT | |

| 6 | Sense | GGCACTCTGAGGAAAGGGGGTGAAACCAGCTGAGAAGTCA |

| Antisense | TGACTTCTCAGCTGGTTTCACCCCCTTTCCTCAGAGTGCC | |

| 7 | Sense | AGTCATCTTTTACCTGCTGGCATGGCCCCAGCCAGGGTTC |

| Antisense | GAACCCTGGCTGGGGCCATGCCAGCAGGTAAAAGATGACT | |

| 8 | Sense | CCCCAGCCAGGGTTCTGTTGCTATGGGAGAATGGGTGAGT |

| Antisense | ACTCACCCATTCTCCCATAGCAACAGAACCCTGGCTGGGG | |

| 9 | Sense | TCTCTCCCGGTTATTAATTAATTAACTAAAATTAAATTAT |

| Antisense | ATAATTTAATTTTAGTTAATTAATTAATAACCGGGAGAGA | |

| 10 | Sense | AATTATTTAGTTAATTTAATTAACTAAACTAATGGGTGAG |

| Antisense | CTCACCCATTAGTTTAGTTAATTAAATTAACTAAATAATT |

RT-PCR

The iPSCs were removed from the feeder cells and were rinsed twice with PBS. Total cellular RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA concentrations were determined by measuring absorption values at 260 nm/280 nm. Reverse transcription was performed using a SuperScript first strand synthesis system for RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen). Primer sequences for human OCT3/4, NANOG, SOX2, and GAPDH as well as the associated PCR detection methods were created and performed according to Seki et al. (21). The primers used to detect human HTRA1 included AACTTTATCGCGGACGTGGTGGAG (forward) and TGATGGCGTCGGTCTGGATGTAGT (reverse).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from human iPSCs with an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. An aliquot of each sample was reverse-transcribed using a high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Invitrogen) to obtain single-stranded cDNAs. Using an ABI STEP-One real-time PCR system (Invitrogen) with TaqMan probes for human HTRA1, quantitative RT-PCR was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. All of the reactions were run in triplicate using the ΔCt method, and detection of human GAPDH was used as an internal control.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

Nuclear extract of 661W cells (50 μg) was combined with 100 pmol of biotin-labeled, double-stranded DNA probes in DNAP buffer (20 mm HEPES, 80 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl, 0.2 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.5 mm DTT). This proteins/probes mixture was incubated at 4 °C for 30 min before 50 ml of Dynabeads M280 streptavidin (Invitrogen) was added. The mixture was incubated at 4 °C for 30 min. The beads-probes-protein complex was then washed with 500 μl of DNAP buffer three times for 30 min at 4 °C. The washed complexes were mixed with 30 μl of SDS-PAGE sample buffer (Bio-Rad) and were boiled for 5 min at 100 °C. The boiled samples were quenched on ice for 5 min before being separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE. Bands of interest were cut out of the gel and were processed for in-gel digestion for further LC-MS/MS analysis. A Thermo LTQ system (Thermo Scientific) and Scaffold 4 data analysis software (Matrix Science) were used.

Immunohistochemistry

Eyes from wild type, HtrA1 knock-out, and HtrA1 transgenic mice (12, 16, 23) were resected and immersed in a fixative containing 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C. The eyes were embedded in OCT compound and frozen on dry ice. Sections of the frozen eyes (10 μm) were washed with 0.1% Tween 20, PBS (PBST) prior to permeabilization with 0.3% Triton X-100, PBS for 15 min. After the sections were washed in 0.1% PBST, they were incubated with blocking solution for 1 h, followed by an overnight incubation at 4 °C with anti-rabbit HtrA1 antibodies (Abcam) in PBS, 2% BSA. The sections were washed in 0.1% PBST three times and then were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (1:1000; Invitrogen) and DAPI (Dojindo, Japan) for nuclear staining at room temperature. After 1 h, the sections were mounted with Ultramount aqueous permanent mounting medium (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) and were analyzed using a confocal fluorescence laser microscope (LSM 700, Zeiss).

In Situ Hybridization

Eyes from HtrA1 heterozygous mice were removed and immersed in 5% formaldehyde overnight at 4 °C. The eyes were then embedded in paraffin and sectioned (10 μm). In situ hybridization was performed using a QuantiGeneTM ViewRNA system (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) using HtrA1 and LacZ probes according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western Blotting

Total proteins were extracted from mouse brain tissues in ice-cold TNE buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm EDTA, 0.1% Nonidet P-40) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). Protein concentrations of the extracts were determined using a BCA assay kit (Thermo Scientific). Equal amounts of protein (10 μg/lane) were separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE and were transferred to PVDF membranes (Trans-Blot Turbo, Bio-Rad). The membranes were then incubated with an anti-mouse HtrA1 antibody (1:100; Abcam) and an anti-α-tubulin antibody (1:1000; Abcam). A FluorChem Western blot imaging station (ChemiDoc XRS+, Bio-Rad) and image analysis software (Image Lab, Bio-Rad) were used to calculate and normalize the pixel value of each protein band.

RESULTS

Sequencing of ARMS2-HTRA1 Loci in Controls and AMD Patients

To determine the genomic sequence of the LD block represented by the SNP, rs10490924, in association with AMD (6, 19, 24), ∼10.5 kbp of the LD block (NC_000010.10) was sequenced for 228 controls and 226 AMD patients. Two unique sequences were identified in the regulatory region of ARMS2 and HTRA1 (Fig. 1). A C-to-A (C/A) variant was identified in the regulatory region of ARMS2, −550 bp upstream of exon 1 (Fig. 1, A and B), and an insertion/deletion variant was identified immediately following the ARMS2 exon 2 in the regulatory region of HTRA1, −3777 bp upstream of exon 1 (Fig. 1, A and C). Sequence variations in both transcription regulators were in complete LD with SNP rs10490924, thereby suggesting that AMD and PCV pathogenesis are directly associated with these variants.

The Effect of C/A and Insertion/Deletion Variants on ARMS2 and HTRA1 Regulatory Region Activity

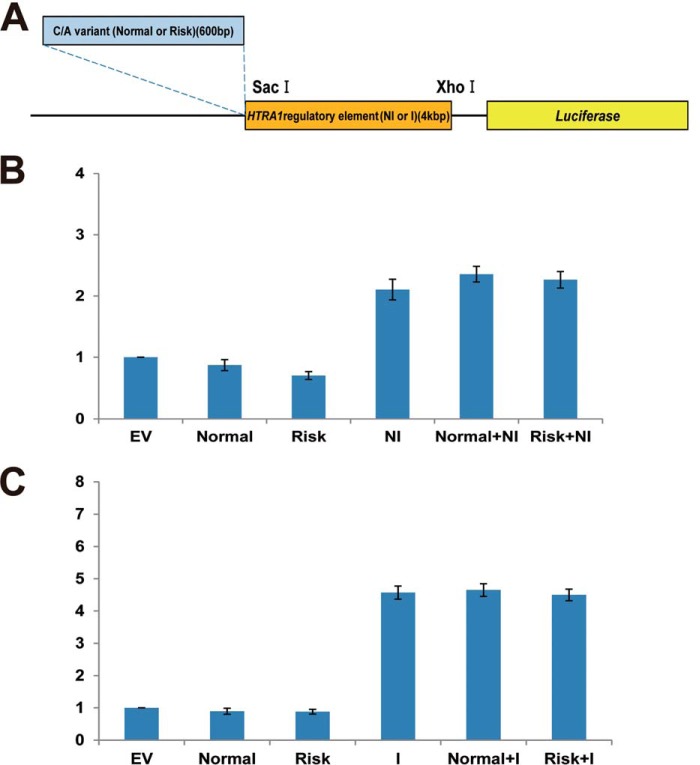

To date, two hypotheses have been proposed to account for the increased risk of AMD that is observed. These involve an increase in the transcription of HTRA1 and/or the presence of unstable ARMS2 mRNA (7, 19, 24). To investigate the first hypothesis, regulator activity for ARMS2 was assayed using constructs covering the regulatory region from −1,000 to +1 bp and from −600 to +1 bp. Both of these regions contain the C/A repetitive variant (Fig. 1D). Regulatory region activity was not detected for either the non-C/A or C/A variants of differing length for retinal cell lines (ARPE19, 661W, and RGC5 tested) (Fig. 1, E–G). Next, regulator activity of HTRA1 was assayed for the −4,320 to +1 bp region of the non-insertion/deletion regulatory region and for the −3,936 to +1 bp region of the insertion/deletion regulatory region (Fig. 1H). Both regions had common sequences on both ends of the regulatory region. Transcription regulator activity was not found to be affected by the insertion/deletion variants in the ARPE19 cell line (Fig. 1I). However, activity of the insertion/deletion regulator was significantly up-regulated compared with the activity of the non-insertion/deletion regulator in both the 661W and RGC5 cell lines, by ∼2- and 3-fold, respectively (Fig. 1, J and K). Moreover, HTRA1 non-insertion/deletion regulator activity was not detected in the latter, similar to the empty vector. However, when the non-insertion/deletion regulator was replaced with the insertion/deletion regulator in the 661W and RGC5 cell lines, HTRA1 regulatory element activity increased 2- and 3-fold, respectively (Fig. 1J). To test whether C/A variants in the transcription regulatory region of ARMS2 influence HTRA1 gene expression, both normal and risk type ARMS2 C/A variant (Fig. 2A) were cloned and fused to the HTRA1 transcription regulator of the non-insertion/deletion and insertion/deletion constructs. Luciferase levels were subsequently measured following transfection of these vectors (Fig. 2A). Neither the normal nor the risk type, C/A variants affected HTRA1 transcription regulator activity (Fig. 2, B and C).

FIGURE 2.

The effect of the ARMS2 C/A variant on the HTRA1 transcription regulator. A, schematic diagram of the C/A variant plus HTRA1 regulatory element in the constructs used for luciferase assays (blue region, 600-bp AMRS2 transcription regulatory region (contains C/A variant); orange region, region that contains the HTRA1 regulatory element; yellow region, the luciferase reporter gene). B, C/A variant plus non-insertion/deletion type HTRA1 regulatory element activity in 661W cells. C, C/A variant plus insertion/deletion type HTRA1 regulatory element activity in 661W cells. Error bars, S.D. EV, empty vector; Normal, normal type C/A variant; Risk, risk type C/A variant; NI, non-insertion/deletion type HTRA1 regulatory element; I, insertion/deletion type HTRA1 regulatory element.

Endogenous Transcription Regulator Activity and Protein and mRNA Expression of HtrA1 in Mouse Retina Tissues

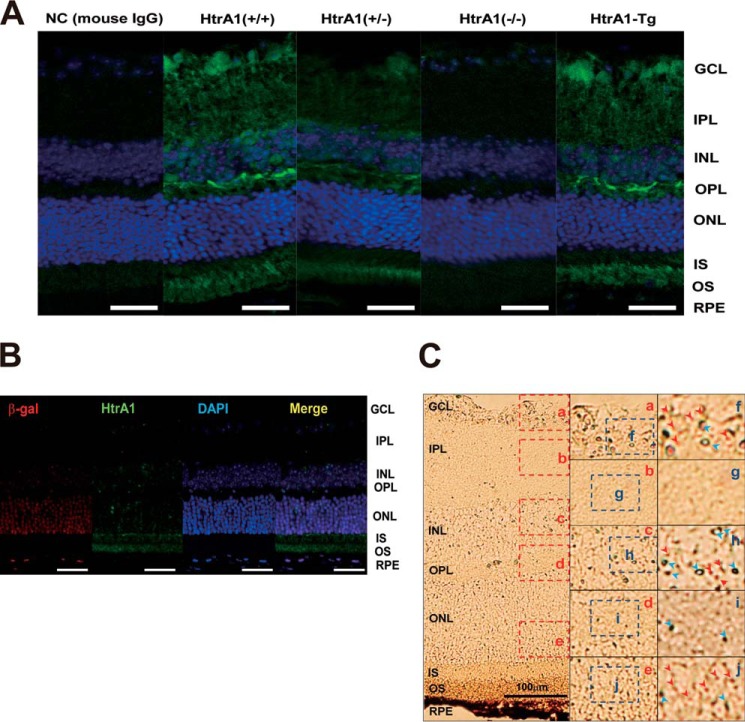

To examine the localization of HtrA1 in the retina, eye sections from both wild type and mutant (HtrA1 knock-out, HtrA1 transgenic) mice were stained with an anti-mouse HtrA1 antibody (Fig. 3A). In both wild type and HtrA1-Tg mouse sections, HtrA1 expression was observed to localize to the photoreceptor cell layer (outer segment (OS) and inner segment (IS) in Fig. 3), the outer plexiform layer (OPL), and the ganglion cell layer (GCL). In contrast, HtrA1 expression in eye tissues from heterozygous HtrA1 mice was mainly localized to the photoreceptor cell layer and the outer plexiform layer, whereas minor expression of HtrA1 was observed in the ganglion cell layer.

FIGURE 3.

Htra1 transcription regulator activity and Htra1 protein expression in the mouse retina. A, immunohistochemistry to detect HtrA1 expression in HtrA1+/+, HtrA1+/−, HtrA1−/−, and HtrA1-Tg mouse retinas (blue, DAPI; green, HtrA1). NC (mouse IgG), staining control; scale bars, 100 μm. B, immunohistochemistry to detect HtrA1 expression in HtrA1+/− mouse retinas (red, β-galactosidase; green: HtrA1; blue, DAPI; yellow, merge). Scale bars, 100 μm. C, in situ hybridization to detect HtrA1 expression in HtrA1+/− mouse retina tissues (red arrowheads, HtrA1; blue arrowheads, β-galactosidase). Scale bars, 100 μm. OS, outer segment; IS, inner segment; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer.

To localize HtrA1 transcription regulator activity in the retina, a heterozygous HtrA1 knock-out mouse construct that included β-galactosidase (β-gal) cDNA (LacZ) in place of exon 1 of Htra1 was used. β-Gal protein was abundantly expressed in the outer nuclear layer (ONL), and lower levels of expression were observed in the RPE, the inner nuclear layer (INL), and the retinal ganglion cell layer (GCL) (Fig. 3B). In comparison, native HtrA1 protein was abundantly expressed in the OS and IS, with lower expression levels detected in the RPE, the outer plexiform layer (OPL), the inner plexiform layer (IPL), and the ganglion cell layer (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, abundant transcription of HtrA1 mRNA was detected by in situ hybridization in retinal sections from a HtrA1 heterozygous knock-out mouse (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these results suggest that HtrA1 is transcribed mainly in the outer nuclear layer, outer plexiform layer, and ganglion cell layer, and then the protein product is transported to the photoreceptor layer.

Identification of Suppressing and Activating cis-Elements in the HTRA1 Regulatory Element

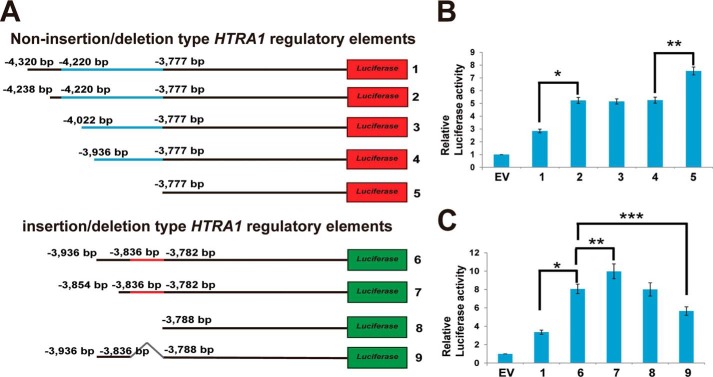

To analyze the mechanism of insertion/deletion function in the HTRA1 regulatory region, both non-insertion/deletion (1, bp −4,320 to +1; 2, bp −4,238 to +1; 3, bp −4,022 to +1; 4, bp −3,936 to +1; 5, bp −3,777 to +1) and insertion/deletion (6, bp −3,936 to +1; 7, bp −3,854 to +1; 8, bp −3,788 to +1; 9, bp −3,836 to −3,788 defect mutant) regions were cloned into a pGL4.10[luc2] luciferase assay vector (Fig. 4A). These cloned vectors were then transfected into 661W cells and were analyzed for HTRA1 transcription regulator activity. The activity of the number 2 region (bp −4,320 to −4,239) non-insertion/deletion defect HTRA1 transcription regulator was 1.8–2-fold higher than that of the number 1 region, and transcription regulator activity did not differ between the number 2, 3, and 4 variants (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the activity of the number 5 transcription regulator was 20–30% higher than that of the number 4 variant (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Enhanced HTRA1 transcription regulator activity is associated with the insertion/deletion variant in the photoreceptor cell line, 661W. A, constructs used for luciferase assay analysis (black line, common sequence between both regulators; blue line, non-insertion/deletion regulator (443 bp); red line, insertion/deletion regulator (54 bp); red boxes 1–5, non-insertion/deletion regulator constructs; green boxes 6–9, insertion/deletion regulator constructs; gray line 9, insertion/deletion region). B and C, transcription regulator activity detected for the non-insertion/deletion and insertion/deletion HTRA1 transcription regulator assayed (in B, *, p = 1.05 × 10−6; **, p = 3.46 × 10−5; in C, *, p = 2.2 × 10−6; **, p = 0.0086; ***, p = 0.0062). EV, empty vector; error bars, S.D.

In addition, activity of the number 6 insertion/deletion type HTRA1 transcription regulator was 2- and 3-fold higher than that of the number 1 non-insertion/deletion type transcription regulator in 661W cells (Figs. 1K and 4C). Furthermore, activity of the number 7 (bp −3,936 to −3,855 defect) region was 10% higher than that of the number 6 region, and activity of the number 8 (bp −3,936 to −3,789 defect) region was lower than that of the number 7 region (Fig. 4C). In addition, the activity of the number 9 (insertion/deletion defect) region was 10–20% lower than that of the number 6 insertion/deletion type transcription regulator (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these results suggest that both of the non-insertion/deletion type regions (including bp −4,320 to −4,239 and bp −3,936 to −3,778 bp) may be regulated by suppressor factors, whereas the insertion/deletion type region from bp −3,836 to −3,789 may bind an enhancer.

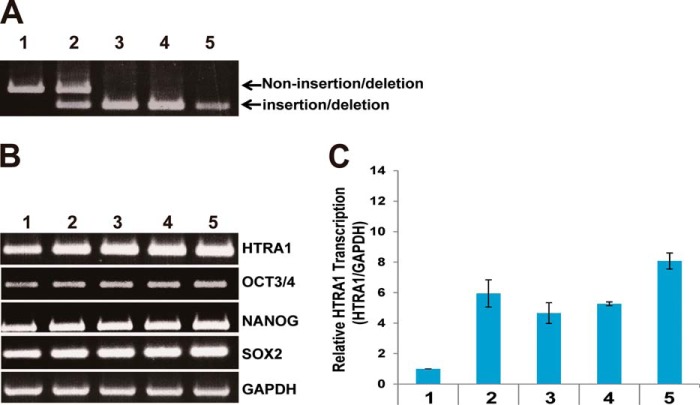

Endogenous HTRA1 Expression Is Enhanced by the Insertion/Deletion Type Regulatory Element in AMD Patient iPSCs

To determine the level of HTRA1 expression in individuals with a non-insertion/deletion type regulatory element sequence, iPSCs heterozygous and homozygous for the insertion/deletion type regulatory element sequence were subjected to genotyping. From both control and AMD patients, iPSCs were collected and categorized as having a non-insertion/deletion or insertion/deletion genotype (Fig. 5A). These cells were also assayed for expression of the iPSCs markers, OCT3/4, NANOG, and SOX2 (Fig. 5B), and levels of HTRA1 mRNA were measured by RT-PCR and quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 5, B and C). Individuals with heterozygous or homozygous HTRA1 insertion/deletion type sequences showed an approximately 6- and 7-fold increase in HTRA1 mRNA levels, respectively, compared with individuals having the non-insertion/deletion type sequence (Fig. 5C). In contrast, expression of HTRA1 mRNA was not influenced by the heterozygous or homozygous state of the insertion/deletion type sequence.

FIGURE 5.

HTRA1 transcription in human iPSCs derived from wet AMD patients. A, genotyping of non-insertion/deletion versus insertion/deletion versions of the human HTRA1 gene transcription regulatory region. B, detection of human iPSC marker genes by RT-PCR. Detection of GAPDH was used as an internal control. C, relative transcriptional level of HTRA1 determined by quantitative RT-PCR for iPSCs derived from individuals with non-insertion/deletion (control) versus insertion/deletion (wet AMD) transcription regulators. Sample 1, 30-year-old non-AMD male; sample 2, 72-year-old wet AMD female; sample 3, 38-year-old non-AMD male; sample 4, 71-year-old non-AMD female; sample 5, 71-year-old wet AMD female. Error bars, S.D.

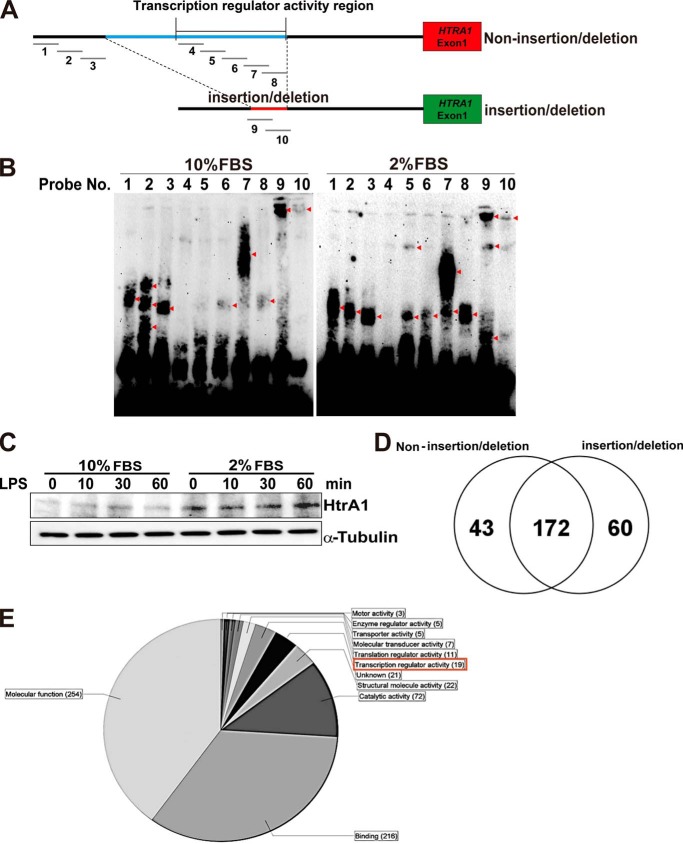

Analysis of Regulatory Element-binding Proteins

To detect proteins that bind the HTRA1 regulatory element, EMSAs were performed. Ten 3′-biotin-labeled double-stranded DNA probes were generated in order to assay the transcriptional activity of each region of the HTRA1 regulatory element (Figs. 4 (B and C) and 6A and Table 3). In addition to the use of 661W nuclear extracts in these assays, extracts of 661W cells grown in 10% FBS versus 2% FBS were also assayed; the latter conditions were included based on the observation that HTRA1 family proteins are known to mediate various stress response signaling pathways (25–28). Thus, we tested 661W cell protein-probe binding activity in a cell-stressful environment. Protein-probe binding signals were detected for probes 1–3 and 6–10 (Fig. 6A) in the presence of nuclear extracts from normally cultured 661W cells (Fig. 6B, left). These results suggest that the binding pattern of the insertion/deletion sequence (included in probes 4–8) may differ greatly from that of the non-insertion/deletion type sequence (number 9 and 10 probes). When the culturing conditions for the 661W cells were changed from 10% to 2% FBS, this drastically altered the protein-probe binding signal pattern obtained (Fig. 6B, right). For example, a reduction in FBS concentration resulted in the loss of two of three signals for the number 2 probe, and it altered the probe-protein binding pattern of probes 5–9. Detection of HtrA1 expression further demonstrated that HtrA1 expression was enhanced in 661W cells following starvation stress (Fig. 6C). Signaling pathways involving the Toll-like receptor (TLR) family of proteins have been shown to be associated with AMD pathogenesis (29), and 661W cells are known to express TLR-4 (30). Therefore, HtrA1 expression was assayed in 661W cells following stimulation with a TLR-4 ligand, lipopolysaccharide (LPS). However, HtrA1 expression was unaffected by this stimulation (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Identification of the transcription factors binding to non-insertion/deletion and insertion/deletion regions of the HTRA1 transcription regulators. A, location of the double-stranded DNA probes, 1–10, in the region upstream of the HTRA1 coding region that were designed for EMSAs. Both non-insertion/deletion and insertion/deletion HTRA1 transcription regulatory regions were targeted. B, EMSAs of probes 1–10 using nuclear extracts from 661W cells cultured in 2 and 10% FBS. Red arrowheads, detected signals. C, increased expression of HtrA1 was detected in Western blot assays performed following treatment of 661W cells with LPS (1 μg/ml, 0–60 min) using anti-mouse HtrA1 antibodies. Detection of α-tubulin was used as an internal control. D, a Venn diagram shows the number of proteins found to bind the non-insertion/deletion versus insertion/deletion regions of the HTRA1 transcription regulator based on LC-MS/MS data. E, gene ontology term of non-insertion/deletion- and insertion/deletion-binding protein (categorized by molecular function).

To identify the proteins that bind the regulatory element region of HTRA1, both non-insertion/deletion and insertion/deletion sequence-binding factors were analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Non-insertion/deletion-binding protein samples were incubated with probes 4–8, whereas the insertion/deletion-binding protein samples were incubated with probes 9 and 10 (Fig. 6A). A total of 172 common binding proteins, 43 non-insertion/deletion probe-specific binding proteins, and 60 insertion/deletion probe-specific binding proteins were identified (Fig. 6D). Using Scaffold 4 software, 19 transcriptional regulator proteins were detected (according to gene ontology (see the Gene Ontology Consortium Web site)) (Fig. 6E). These 19 factors were then classified according to their binding sequence (Tables 4–6). Six non-insertion/deletion-binding probes were found to bind PURB, NFIC, RUNX2, PEBB, APEX1, and RBM14 proteins (Table 4), whereas three insertion/deletion-binding probes were found to bind LYRIC (lysine-rich CEACAM1 co-isolated) protein, MED4, and PHF2 (Table 5). Ten additional proteins were found to bind both the non-insertion/deletion and insertion/deletion probes: ROAA, SHOX2, CUX1, DDX5, DDX1, MED24, RBM39, JMY, TCP4, and DDX17 (Table 6). In combination, these results suggest that expression of HtrA1 is influenced by factors that specifically bind this region and affect gene expression.

TABLE 4.

Non-insertion/deletion probe binding proteins

| MS/MS view: identified proteins | Symbol | Molecular mass | Taxonomy | Biological regulation | Binding | Molecular function | Transcription regulator activity | Peptide hit score (non-indel)a | Peptide Hit Score (indel) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kDa | |||||||||

| Transcriptional activator protein Pur-β | PURB | 34 | M. musculus | Regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | Protein binding | Transcription factor activity | Transcription factor activity | 3 | 0 |

| Nuclear factor 1 C-type | NFIC | 49 | M. musculus | Regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | Transcription factor activity | Transcription factor activity | Transcription factor activity | 3 | 0 |

| Runt-related transcription factor 2 | RUNX2 | 66 | M. musculus | Positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | Protein binding | Transcription factor activity | Transcription factor activity | 2 | 0 |

| Core-binding factor subunit β | PEBB | 22 | M. musculus | Positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | DNA binding | Transcription coactivator activity | Transcription coactivator activity | 1 | 0 |

| DNA-(apurinic or apyrimidinic site) lyase | APEX1 | 35 | M. musculus | Cell redox homeostasis | Chromatin DNA binding | Transcription coactivator activity | Transcription coactivator activity | 1 | 0 |

| RNA-binding protein 14 | RBM14 | 69 | M. musculus | Regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | Nucleic acid binding | Ligand-dependent nuclear receptor transcription coactivator activity | Ligand-dependent nuclear receptor transcription coactivator activity | 1 | 0 |

a indel, insertion/deletion.

TABLE 5.

Insertion/deletion probe binding proteins

| MS/MS view: identified proteins | Symbol | Molecular mass | Taxonomy | Biological regulation | Binding | Molecular function | Transcription Regulator Activity | Peptide Hit Score (non-indel)a | Peptide Hit Score (indel) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kDa | |||||||||

| Protein LYRIC | LYRIC | 64 | M. musculus | Positive regulation of NF-κB transcription factor activity | Nucleolus | Protein binding | Transcription coactivator activity | 0 | 20 |

| Mediator of RNA polymerase II transcription subunit 4 | MED4 | 30 | M. musculus | Androgen receptor signaling pathway | Thyroid hormone receptor binding | Transcription cofactor activity | Transcription cofactor activity | 0 | 2 |

| Lysine-specific demethylase PHF2 | PHF2 | 121 | M. musculus | Regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | Methylated histone residue binding | Transcription coactivator activity | Transcription coactivator activity | 0 | 1 |

a indel, insertion/deletion.

TABLE 6.

Non-insertion/deletion-probe and insertion/deletion probe-binding proteins

| MS/MS view: identified proteins | Symbol | Molecular mass | Taxonomy | Biological regulation | Binding | Molecular Function | Transcription Regulator Activity | Peptide hit score (non-indel)a | Peptide hit score (indel) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kDa | |||||||||

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A/B | HNRPAB | 31 | M. musculus | Regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | Nucleic acid binding | Transcription factor activity | Transcription factor activity | 25 | 24 |

| Short stature homeobox protein 2 | SHOX2 | 35 | M. musculus | Positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | DNA binding | Transcription factor activity | Transcription factor activity | 2 | 1 |

| Homeobox protein cut-like 1 | CUX1 | 166 | M. musculus | Negative regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | Chromatin binding | Transcription factor activity | Transcription factor activity | 6 | 1 |

| Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX5 | DDX5 | 69 | M. musculus | Regulation of alternative nuclear mRNA splicing, via spliceosome | Nucleic acid binding | Transcription coactivator activity | Transcription cofactor activity | 14 | 36 |

| ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX1 | DDX1 | 83 | M. musculus | Regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | Chromatin binding | Transcription cofactor activity | Transcription cofactor activity | 28 | 12 |

| Mediator of RNA polymerase II transcription subunit 24 | MED24 | 110 | M. musculus | Stem cell maintenance | Thyroid hormone receptor binding | Receptor activity | Transcription cofactor activity | 1 | 1 |

| RNA-binding protein 39 | RBM39 | 59 | M. musculus | Regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | Nucleic acid binding | Transcription coactivator activity | Transcription coactivator activity | 10 | 9 |

| Junction-mediating and -regulatory protein | JMY | 111 | M. musculus | Positive regulation of transcription factor activity | Protein binding | Transcription coactivator activity | Transcription coactivator activity | 1 | 1 |

| Activated RNA polymerase II transcriptional coactivator p15 | TCP4 | 14 | M. musculus | Regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | DNA binding | Transcription coactivator activity | Transcription coactivator activity | 1 | 2 |

| Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX17 | DDX17 | 72 | M. musculus | Regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | Nucleic acid binding | Hydrolase activity | Transcription coactivator activity | 1 | 1 |

a indel, insertion/deletion.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, the present study provides the first detailed characterization of regulatory elements for HTRA1 and the effect of insertion/deletion sequences associated with wet AMD. The insertion/deletion variant that exhibited complete association with the SNP, rs10490924, is the only major sequence change in this LD block and is likely to play a major role in disease onset. Moreover, the insertion/deletion variant in close proximity to ARMS2 and HTRA1 has been at the center of the discussion of whether one or both genes are involved in AMD (19, 24). In the present study, the ARMS2 transcription regulator exhibited only marginal activity in each of the cell lines tested, whereas robust up-regulation of HTRA1 transcription regulator activity was observed in iPSCs derived from AMD patients containing heterozygous or homozygous forms of the insertion/deletion. Up-regulation of HTRA1 in the earliest stages of development is predicted to affect the entire body (31).

HTRA1 is known to be a TGF-β suppression factor, and some reports have suggested that HtrA1 is expressed in skeletal, brain, lung epithelium, heart, and skin tissues in fetal mice (31). Other reports have suggested that HTRA1 is involved in bone remodeling (e.g. RANK/RANKL signal-derived osteoclast bone absorption and osteoblast differentiation) (32) and oncogenesis in liver and lung cancers (33, 34). Thus, HTRA1 may play an important role in cell growth and differentiation, tissue and/or organ formation, and the onset of disorders. Correspondingly, a transgenic mouse with expression of mouse HtrA1 driven by a chicken actin (CAG) promoter was used to establish a model for choroidal neovascularization, and this model exhibited a significant reduction in tolerance to smoking (23).

Detailed characterization of the transcription regulator activity that surrounds the HTRA1 insertion/deletion sequence showed that suppressive regions are located between bp −4,320 and −4,239 and between bp −3,936 and −3,778 in the non-insertion/deletion sequence and between bp −3,936 and −3,854 for the insertion/deletion sequence. In addition, the insertion/deletion located between bp −3,836 and −3,783 exhibited transcription regulator activity unique to the insertion/deletion sequence (Fig. 4). An analysis of these results showed that the insertion/deletion variant interrupts a suppressor cis-element and replaces it with an activator, and this significantly alters HTRA1 transcription in the photoreceptor. The EMSA and LC-MS/MS data also suggest that HTRA1 regulatory element activity is regulated by a number of transcription factors (Fig. 6 and Tables 4–6).

When the proteins that bound the regulatory elements of the non-insertion/deletion and insertion/deletion sequences of HTRA1 were analyzed using LC-MS/MS, LYRIC (also known as MTDH/AEG1) was a high hit score insertion/deletion-binding protein that was identified (Table 5). LYRIC is known to promote hepatocellular carcinoma and to activate the transcription factor, nuclear factor κ-B (NF-κB), and also has an effect on bone and brain metastasis (35–37). Regarding the latter, LYRIC may enhance the seeding of tumor cells at the target organ endothelium. LYRIC also contributes to HIF-1α-mediated angiogenesis (38), with HIF-1α playing an important role in the activation of VEGF signaling in response to oxidative stress (39). Recently, Oka et al. (25) reported that HTRA1 gene expression is enhanced by oxidative stress. This result is consistent with the observation that AMD onset is associated with a variety of stresses, and stress response factors may play an important role.

Both common sequences (non-insertion/deletion (bp −4,320 to −4,220) and insertion/deletion (bp −3,936 to −3,836 bp)) and the insertion/deletion sequence (bp −3,836 to −3,782 bp) are partially associated with ARMS2 exon 2, thereby indicating that this exon represents a protein-coding region and a HTRA1 regulatory element region. Recent reports have suggested that both an increase in HTRA1 transcription and a decrease in ARMS2 transcription confer an increased risk of AMD (8). These insights suggest that ARMS2 gene expression may be regulated by HTRA1 transcription regulator activity via the ARMS2 exon 2 region.

AMD pathogenesis and previous HTRA1 experiments related to AMD have been performed and discussed in relation to the RPE (8, 16, 17). However, immunostaining of HTRA1 in mouse retinas in the present study showed that the majority of transcription occurs in the photoreceptor cell layer (Fig. 3). This result was confirmed when higher levels of transcription from the HTRA1 insertion/deletion regulator were observed in the photoreceptor cell line: 661W cells versus the RPE cells (Fig. 1, I–K). Photoreceptors are densely concentrated in the macula (40), which predicts that HTRA1 will also be concentrated in the macula. A recent report using transgenic mice overexpressing human HTRA1 in the RPE showed that PCV-like capillary structures could be observed in the choroid. Vierkotten et al. (17) also observed fragmentation of the elastic layer in Bruch's membrane, and Jones et al. (16) reported branching of choroidal vessels, polypoidal lesions, and severe degeneration of the elastic lamina or tunica media of choroidal vessels in the same model. When HtrA1 expression was driven by the CAG promoter in a transgenic mouse model, an even more severe phenotype was induced compared with previous reports of AMD patient-like choroidal neovascularization (23). These results indicate that overexpression of HtrA1 alone can evoke choroidal vasculopathy or neovascularization, and they also provide supporting evidence for the association of the insertion/deletion variant of HTRA1 regulatory element with wet AMD (7, 8).

This work was supported by Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare Grant 10103254 and National Hospital Organization of Japan Grant 09005752 (to T. I.). This work was also supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grant 23890258 (to D. I.).

- AMD

- age-related macular degeneration

- LD

- linkage disequilibrium

- RPE

- retinal pigment epithelium

- PCV

- polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy

- iPSC

- induced pluripotent stem cell

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fritsche L. G., Chen W., Schu M., Yaspan B. L., Yu Y., Thorleifsson G., Zack D. J., Arakawa S., Cipriani V., Ripke S., Igo R. P., Jr., Buitendijk G. H., Sim X., Weeks D. E., Guymer R. H., Merriam J. E., Francis P. J., Hannum G., Agarwal A., Armbrecht A. M., Audo I., Aung T., Barile G. R., Benchaboune M., Bird A. C., Bishop P. N., Branham K. E., Brooks M., Brucker A. J., Cade W. H., Cain M. S., Campochiaro P. A., Chan C. C., Cheng C. Y., Chew E. Y., Chin K. A., Chowers I., Clayton D. G., Cojocaru R., Conley Y. P., Cornes B. K., Daly M. J., Dhillon B., Edwards A. O., Evangelou E., Fagerness J., Ferreyra H. A., Friedman J. S., Geirsdottir A., George R. J., Gieger C., Gupta N., Hagstrom S. A., Harding S. P., Haritoglou C., Heckenlively J. R., Holz F. G., Hughes G., Ioannidis J. P., Ishibashi T., Joseph P., Jun G., Kamatani Y., Katsanis N., C N. K., Khan J. C., Kim I. K., Kiyohara Y., Klein B. E., Klein R., Kovach J. L., Kozak I., Lee C. J., Lee K. E., Lichtner P., Lotery A. J., Meitinger T., Mitchell P., Mohand-Said S., Moore A. T., Morgan D. J., Morrison M. A., Myers C. E., Naj A. C., Nakamura Y., Okada Y., Orlin A., Ortube M. C., Othman M. I., Pappas C., Park K. H., Pauer G. J., Peachey N. S., Poch O., Priya R. R., Reynolds R., Richardson A. J., Ripp R., Rudolph G., Ryu E., Sahel J. A., Schaumberg D. A., Scholl H. P., Schwartz S. G., Scott W. K., Shahid H., Sigurdsson H., Silvestri G., Sivakumaran T. A., Smith R. T., Sobrin L., Souied E. H., Stambolian D. E., Stefansson H., Sturgill-Short G. M., Takahashi A., Tosakulwong N., Truitt B. J., Tsironi E. E., Uitterlinden A. G., van Duijn C. M., Vijaya L., Vingerling J. R., Vithana E. N., Webster A. R., Wichmann H. E., Winkler T. W., Wong T. Y., Wright A. F., Zelenika D., Zhang M., Zhao L., Zhang K., Klein M. L., Hageman G. S., Lathrop G. M., Stefansson K., Allikmets R., Baird P. N., Gorin M. B., Wang J. J., Klaver C. C., Seddon J. M., Pericak-Vance M. A., Iyengar S. K., Yates J. R., Swaroop A., Weber B. H., Kubo M., Deangelis M. M., Leveillard T., Thorsteinsdottir U., Haines J. L., Farrer L. A., Heid I. M., Abecasis G. R. (2013) Seven new loci associated with age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Genet. 10.1038/ng.2578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Klein R. J., Zeiss C., Chew E. Y., Tsai J. Y., Sackler R. S., Haynes C., Henning A. K., SanGiovanni J. P., Mane S. M., Mayne S. T., Bracken M. B., Ferris F. L., Ott J., Barnstable C., Hoh J. (2005) Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science 308, 385–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hageman G. S., Anderson D. H., Johnson L. V., Hancox L. S., Taiber A. J., Hardisty L. I., Hageman J. L., Stockman H. A., Borchardt J. D., Gehrs K. M., Smith R. J., Silvestri G., Russell S. R., Klaver C. C., Barbazetto I., Chang S., Yannuzzi L. A., Barile G. R., Merriam J. C., Smith R. T., Olsh A. K., Bergeron J., Zernant J., Merriam J. E., Gold B., Dean M., Allikmets R. (2005) A common haplotype in the complement regulatory gene factor H (HF1/CFH) predisposes individuals to age-related macular degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 7227–7232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Okamoto H., Umeda S., Obazawa M., Minami M., Noda T., Mizota A., Honda M., Tanaka M., Koyama R., Takagi I., Sakamoto Y., Saito Y., Miyake Y., Iwata T. (2006) Complement factor H polymorphisms in Japanese population with age-related macular degeneration. Mol. Vis. 12, 156–158 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kondo N., Honda S., Ishibashi K., Tsukahara Y., Negi A. (2007) LOC387715/HTRA1 variants in polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy and age-related macular degeneration in a Japanese population. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 144, 608–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goto A., Akahori M., Okamoto H., Minami M., Terauchi N., Haruhata Y., Obazawa M., Noda T., Honda M., Mizota A., Tanaka M., Hayashi T., Tanito M., Ogata N., Iwata T. (2009) Genetic analysis of typical wet-type age-related macular degeneration and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in Japanese population. J. Ocul. Biol. Dis. Infor. 2, 164–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fritsche L. G., Loenhardt T., Janssen A., Fisher S. A., Rivera A., Keilhauer C. N., Weber B. H. (2008) Age-related macular degeneration is associated with an unstable ARMS2 (LOC387715) mRNA. Nat. Genet. 40, 892–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang Z., Tong Z., Chen Y., Zeng J., Lu F., Sun X., Zhao C., Wang K., Davey L., Chen H., London N., Muramatsu D., Salasar F., Carmona R., Kasuga D., Wang X., Bedell M., Dixie M., Zhao P., Yang R., Gibbs D., Liu X., Li Y., Li C., Li Y., Campochiaro B., Constantine R., Zack D. J., Campochiaro P., Fu Y., Li D. Y., Katsanis N., Zhang K. (2010) Genetic and functional dissection of HTRA1 and LOC387715 in age-related macular degeneration. PLoS Genet. 6, e1000836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kanda A., Chen W., Othman M., Branham K. E., Brooks M., Khanna R., He S., Lyons R., Abecasis G. R., Swaroop A. (2007) A variant of mitochondrial protein LOC387715/ARMS2, not HTRA1, is strongly associated with age-related macular degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 16227–16232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kortvely E., Hauck S. M., Duetsch G., Gloeckner C. J., Kremmer E., Alge-Priglinger C. S., Deeg C. A., Ueffing M. (2010) ARMS2 is a constituent of the extracellular matrix providing a link between familial and sporadic age-related macular degenerations. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 79–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shiga A., Nozaki H., Yokoseki A., Nihonmatsu M., Kawata H., Kato T., Koyama A., Arima K., Ikeda M., Katada S., Toyoshima Y., Takahashi H., Tanaka A., Nakano I., Ikeuchi T., Nishizawa M., Onodera O. (2011) Cerebral small-vessel disease protein HTRA1 controls the amount of TGF-β1 via cleavage of proTGF-β1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 1800–1810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang L., Lim S. L., Du H., Zhang M., Kozak I., Hannum G., Wang X., Ouyang H., Hughes G., Zhao L., Zhu X., Lee C., Su Z., Zhou X., Shaw R., Geum D., Wei X., Zhu J., Ideker T., Oka C., Wang N., Yang Z., Shaw P. X., Zhang K. (2012) High temperature requirement factor A1 (HTRA1) gene regulates angiogenesis through transforming growth factor-β family member growth differentiation factor 6. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 1520–1526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jiang J., Huang L., Yu W., Wu X., Zhou P., Li X. (2012) Overexpression of HTRA1 leads to down-regulation of fibronectin and functional changes in RF/6A cells and HUVECs. PLoS One 7, e46115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferrer-Vaquer A., Maurey P., Werzowa J., Firnberg N., Leibbrandt A., Neubüser A. (2008) Expression and regulation of HTRA1 during chick and early mouse development. Dev. Dyn. 237, 1893–1900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chien J., Ota T., Aletti G., Shridhar R., Boccellino M., Quagliuolo L., Baldi A., Shridhar V. (2009) Serine protease HtrA1 associates with microtubules and inhibits cell migration. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 4177–4187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jones A., Kumar S., Zhang N., Tong Z., Yang J. H., Watt C., Anderson J., Amrita, Fillerup H., McCloskey M., Luo L., Yang Z., Ambati B., Marc R., Oka C., Zhang K., Fu Y. (2011) Increased expression of multifunctional serine protease, HTRA1, in retinal pigment epithelium induces polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 14578–14583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vierkotten S., Muether P. S., Fauser S. (2011) Overexpression of HTRA1 leads to ultrastructural changes in the elastic layer of Bruch's membrane via cleavage of extracellular matrix components. PLoS One 6, e22959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hara K., Shiga A., Fukutake T., Nozaki H., Miyashita A., Yokoseki A., Kawata H., Koyama A., Arima K., Takahashi T., Ikeda M., Shiota H., Tamura M., Shimoe Y., Hirayama M., Arisato T., Yanagawa S., Tanaka A., Nakano I., Ikeda S., Yoshida Y., Yamamoto T., Ikeuchi T., Kuwano R., Nishizawa M., Tsuji S., Onodera O. (2009) Association of HTRA1 mutations and familial ischemic cerebral small-vessel disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1729–1739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dewan A., Liu M., Hartman S., Zhang S. S., Liu D. T., Zhao C., Tam P. O., Chan W. M., Lam D. S., Snyder M., Barnstable C., Pang C. P., Hoh J. (2006) HTRA1 promoter polymorphism in wet age-related macular degeneration. Science 314, 989–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Seddon J. M., Ajani U. A., Mitchell B. D. (1997) Familial aggregation of age-related maculopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 123, 199–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Seki T., Yuasa S., Oda M., Egashira T., Yae K., Kusumoto D., Nakata H., Tohyama S., Hashimoto H., Kodaira M., Okada Y., Seimiya H., Fusaki N., Hasegawa M., Fukuda K. (2010) Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human terminally differentiated circulating T cells. Cell Stem Cell 7, 11–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Minegishi Y., Iejima D., Kobayashi H., Chi Z. L., Kawase K., Yamamoto T., Seki T., Yuasa S., Fukuda K., Iwata T. (2013) Enhanced optineurin E50K-TBK1 interaction evokes protein insolubility and initiates familial primary open-angle glaucoma. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 3559–3567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nakayama M., Iejima D., Akahori M., Kamei J., Goto A., Iwata T. (2014) Overexpression of HtrA1 and exposure to mainstream cigarette smoke leads to choroidal neovascularization and subretinal deposits in aged mice. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 55, 6514–6523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yang Z., Camp N. J., Sun H., Tong Z., Gibbs D., Cameron D. J., Chen H., Zhao Y., Pearson E., Li X., Chien J., Dewan A., Harmon J., Bernstein P. S., Shridhar V., Zabriskie N. A., Hoh J., Howes K., Zhang K. (2006) A variant of the HTRA1 gene increases susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Science 314, 992–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Supanji, Shimomachi M., Hasan M. Z., Kawaichi M., Oka C. (2013) HtrA1 is induced by oxidative stress and enhances cell senescence through p38 MAPK pathway. Exp. Eye Res. 112, 79–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hansen G., Hilgenfeld R. (2013) Architecture and regulation of HtrA-family proteins involved in protein quality control and stress response. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 70, 761–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gray C. W., Ward R. V., Karran E., Turconi S., Rowles A., Viglienghi D., Southan C., Barton A., Fantom K. G., West A., Savopoulos J., Hassan N. J., Clinkenbeard H., Hanning C., Amegadzie B., Davis J. B., Dingwall C., Livi G. P., Creasy C. L. (2000) Characterization of human HtrA2, a novel serine protease involved in the mammalian cellular stress response. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 5699–5710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Foucaud-Scheunemann C., Poquet I. (2003) HtrA is a key factor in the response to specific stress conditions in Lactococcus lactis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 224, 53–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kleinman M. E., Kaneko H., Cho W. G., Dridi S., Fowler B. J., Blandford A. D., Albuquerque R. J., Hirano Y., Terasaki H., Kondo M., Fujita T., Ambati B. K., Tarallo V., Gelfand B. D., Bogdanovich S., Baffi J. Z., Ambati J. (2012) Short-interfering RNAs induce retinal degeneration via TLR3 and IRF3. Mol. Ther. 20, 101–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tu Z., Portillo J. A., Howell S., Bu H., Subauste C. S., Al-Ubaidi M. R., Pearlman E., Lin F. (2011) Photoreceptor cells constitutively express functional TLR4. J. Neuroimmunol. 230, 183–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oka C., Tsujimoto R., Kajikawa M., Koshiba-Takeuchi K., Ina J., Yano M., Tsuchiya A., Ueta Y., Soma A., Kanda H., Matsumoto M., Kawaichi M. (2004) HtrA1 serine protease inhibits signaling mediated by Tgfβ family proteins. Development 131, 1041–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu X., Chim S. M., Kuek V., Lim B. S., Chow S. T., Zhao J., Yang S., Rosen V., Tickner J., Xu J. (2014) HtrA1 is upregulated during RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis, and negatively regulates osteoblast differentiation and BMP2-induced Smad1/5/8, ERK and p38 phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 588, 143–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhu F., Jin L., Luo T. P., Luo G. H., Tan Y., Qin X. H. (2010) Serine protease HtrA1 expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 9, 508–512 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xu Y., Jiang Z., Zhang Z., Sun N., Zhang M., Xie J., Li T., Hou Y., Wu D. (2013) HtrA1 downregulation induces cisplatin resistance in lung adenocarcinoma by promoting cancer stem cell-like properties. J. Cell. Biochem. 115, 1112–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ash S. C., Yang D. Q., Britt D. E. (2008) LYRIC/AEG-1 overexpression modulates BCCIPα protein levels in prostate tumor cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 371, 333–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Robertson C. L., Srivastava J., Siddiq A., Gredler R., Emdad L., Rajasekaran D., Akiel M., Shen X. N., Guo C., Giashuddin S., Wang X. Y., Ghosh S., Subler M. A., Windle J. J., Fisher P. B., Sarkar D. (2014) Genetic deletion of AEG-1 prevents hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 74, 6184–6193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Huang Y., Li L. P. (2014) Progress of cancer research on astrocyte elevated gene-1/metadherin (review). Oncol. Lett. 8, 493–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Noch E., Bookland M., Khalili K. (2011) Astrocyte-elevated gene-1 (AEG-1) induction by hypoxia and glucose deprivation in glioblastoma. Cancer Biol. Ther. 11, 32–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Domigan C. K., Iruela-Arispe M. L. (2014) Stealing VEGF from thy neighbor. Cell 159, 473–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li K. Y., Tiruveedhula P., Roorda A. (2010) Intersubject variability of foveal cone photoreceptor density in relation to eye length. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 6858–6867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]