Abstract

A high-sensitivity metal-carbonyl-based IR probe is described that can be incorporated into proteins or other biomolecules in very high yield via Click chemistry. A two-step strategy is demonstrated. First, a methionine auxotroph is used to incorporate the unnatural amino acid azidohomoalanine at high levels. Second, a tricarbonyl (η5-cyclopentadienyl) rhenium(I) probe modified with an alkynyl linkage is coupled via the Click reaction. We demonstrate these steps using the C-terminal domain of the ribosomal protein L9 as a model system. An overall incorporation level of 92% was obtained at residue 109, which is a surface-exposed residue. Incorporation of the probe into a surface site is shown not to perturb the stability or structure of the target protein. Metal carbonyls are known to be sensitive to solvation and protein electrostatics through vibrational lifetimes and frequency shifts. We report that the frequencies and lifetimes of this probe also depend on the isotopic composition of the solvent. Comparison of the lifetimes measured in H2O versus D2O provides a probe of solvent accessibility. The metal carbonyl probe reported here provides an easy and robust method to label very large proteins with an amino-acid-specific tag that is both environmentally sensitive and a very strong absorber.

Introduction

Infrared (IR) spectroscopy is an attractive method for monitoring the environment of biomacromolecules because IR modes are affected by hydrogen bonding, solvation, and the electrostatic environment.1−6 In the past few years, because of the efforts of Skinner and coworkers as well as other researchers, the correlation between environmental electrostatics and vibrational frequencies has been developed to such an extent that it is now possible to quantitatively calculate IR spectra from molecular dynamics simulations using rigorous protocols, thereby allowing for atomic-level interpretations of experimental spectra.7−10 As a result, there is considerable interest in determining structure and probing the environment at specific locations in proteins using IR, which can be accomplished with isotopic substitution or non-natural labels at specific residues. Isotopic labeling with 13C18O backbone labels or C–D groups in side chains can provide site-specific resolution, and these probes are structurally nonperturbative, but it can be difficult to incorporate a single label into a protein.11−17 Small, unnatural amino acids are also commonly used as IR probes, such as azidohomoalanine, p-cyanophenylalanine, p-azidophenylalanine, or thiocyanates, with the latter being introduced via modification of cysteine side chains.18−26 While these probes are small enough to be minimally perturbative and absorb in an otherwise transparent region of the IR spectrum, they have modest extinction coefficients, so that millimolar protein concentrations are usually required. Many proteins are not soluble at such high concentrations, and aggregation can be a major problem. Thus, their use is limited to stable, highly soluble proteins that express well.

We and others have taken an alternative approach and traded size for a strong extinction coefficient by using metal carbonyls as the vibrational tag.27,28 Metal carbonyls offer a very attractive compromise between sensitivity and size; they are larger than standard probes based on unnatural amino acids but are still relatively small and have significantly higher extinction coefficients than standard unnatural amino-acid-based probes or isotopic labels. The frequencies of the metal carbonyl stretches fall in a transparent region of the protein IR spectrum and are well-resolved from water and protein modes. The carbonyl stretch frequencies are sensitive to the electrostatic environment, and their lifetimes are sensitive to solvation. They have been used to study the electrostatic environment and dynamics of a range of biological and nonbiological systems including the dynamics of lipid bilayers, the active site of cytochrome c oxidase, the hydration of ubiquitin and alpha-synuclein, and the dynamics of organic polymers and glasses.27,29−32 A desirable property is their strong extinction coefficient, on the order of 4100 M–1 cm–1, which is considerably larger than that of commonly used probes such as the nitrile (cyano) group, which has an extinction coefficient on the order of 20–240 M–1 cm–1.33,34 The weak oscillator strength of many other probes leads to an even poorer relative signal for higher order spectroscopies, such as two-dimensional infrared (2D IR) spectroscopy, where the signal scales with the fourth power of the transition dipole.35 Thus, metal carbonyl tags enable solvation and environment studies at much lower protein concentrations than are possible with many other vibrational tags.

Metal carbonyls have previously been incorporated into proteins in a number of different ways. They have been attached to lysine, histidine, and cysteine residues with a variety of linkages, including our previous work with a methanethiosulfonate derivative to cysteine.27,28,34,36−43 Linkage via cysteine is the most common way to attach non-native chromophores, but cysteine cannot always be incorporated into proteins because the addition of a cysteine residue can interfere with proper oxidative refolding, and introduction of a cysteine can sometimes lead to undesired disulfide-linked aggregates. A bioorthogonal strategy will be required if multiple probes need to be incorporated specifically. Here we present a simple and general bioorthogonal approach for the selective incorporation of metal carbonyl IR probes in a quantitative yield. The method involves the recombinant incorporation of azidohomoalanine using a methionine auxotrophic E. coli strain together with a newly designed metal carbonyl compound that is attached to the protein via the copper(I)-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition reaction, or Click chemistry.

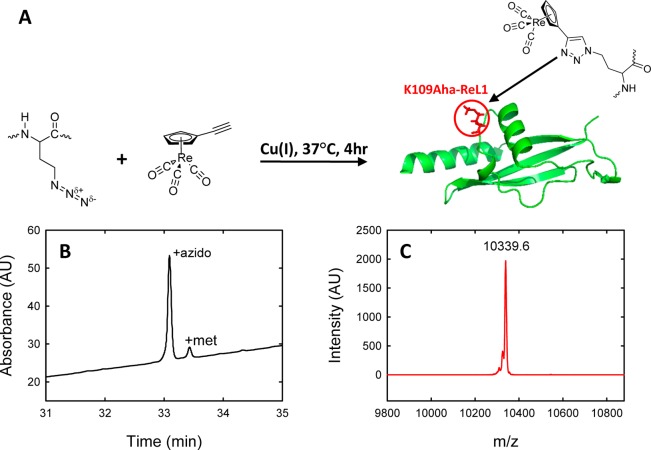

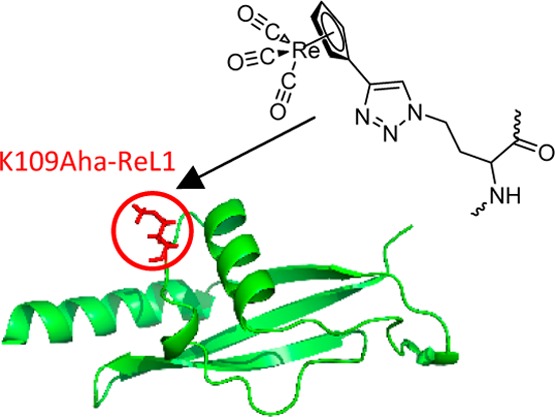

Our strategy is outlined in Figure 1. The protein of interest is modified by the selective incorporation of azidohomoalanine (Aha), the azido analogue of Met. Aha can be recombinantly incorporated into proteins using Met auxotrophs.44,45 The advantage of this approach is that proteins generally express well in Met auxotrophs, although expression yields are usually lower than with nonauxotrophs, and very high levels of Aha incorporation are obtainable. The Click reaction is usually quantitative, resulting in a high level of incorporation of the probe. The disadvantage of the strategy is that the protein cannot contain other Met residues if single specific labeling is desired. However, Met is a relatively rare amino acid and can often be substituted by Leu. Aha can also be incorporated into polypeptides by Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis without the need for a protecting group on the azido side chain.46 We illustrate the approach using the C-terminal domain of the ribosomal protein L9 (CTL9) as a model system (Figure 1). This 92 residue protein forms a mixed α–β structure and folds cooperatively.47,48 We targeted a surface site, residue 109, located in the loop between the second α helix and the second β strand.

Figure 1.

Bioorthogonal incorporation of metal carbonyl IR probes. (A) Schematic representation of the methodology. Azidohomoalanine (Aha) is incorporated using methionine auxotrophs and the probe attached using the Click reaction. The site chosen for substitution in the present case is residue 109 of the protein CTL9, located in a loop. (B) LC trace from the LC–MS analysis of a tryptic digest indicates an incorporation of Aha of 92%. The LC trace is shown for the peptide which contains residue 109. (C) MALDI-TOF mass spectroscopy confirms the identity of the metal carbonyl labeled product. The expected m/z is 10 340.0 and the observed value is 10 339.6.

Experimental Section

Protein Expression and Purification

A copy of the wild-type CTL9 gene in the pET3a plasmid was used for mutagenesis. The codon for lysine at position 109 was mutated to that coding for methionine (ATG) using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis protocol from Stratagene. E. coli B834 cells were transformed with pET3a-CTL9-K109M. Cells were grown in M9 medium to an optical density (OD600) of 0.8 to 1.0 at 37 °C, then harvested and resuspended twice in M9 salt solution. Cells were then resuspended in 1 L of M9 medium supplemented with 17 amino acids (no tyrosine, cysteine, or methionine) and 50 mg of azidohomoalanine (Aha). Cells were lysed, and protein was purified from the supernatant by cation-exchange chromatography, followed by reverse-phase HPLC on a C8 preparative column. For HPLC purification, an A-B gradient system was used in which buffer A consisted of 0.045% (v/v) solution of hydrochloric acid (HCl) in water, and buffer B consisted of 90% (v/v) acetonitrile, 10% (v/v) water, and 0.045 (v/v) HCl. HCl was used as the ion pairing agent instead of TFA as residual TFA can interfere with IR measurements. The expression yield was 23 mg/L. This is ∼30% of the WT expression yield obtained in LB medium.

Preparation of the Metal Carbonyl Probe

General Procedures

All procedures were carried out under a nitrogen atmosphere using Schlenk line techniques. Glassware and needles were oven-dried prior to use. DMF was vacuum-distilled with CaF2. THF was used as received from a solvent purification system. Re2(CO)10 was a gift from Chuck Casey and oxidized to CpRe(CO)3 using a previously reported method.33 All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

(η5-IC5H4)Re(CO)3

A solution of CpRe(CO)3 (780.9 mg) in THF (10 mL) was cooled in a dry ice/acetone bath. n-BuLi (1.6 mL) was added over 10 min, after which the solution was stirred for 20 min. I2(CH2)2 (656 mg) was quickly added. The solution was brought to room temperature and stirred for 30 min. The material was purified with a silica column with hexanes/benzene to yield 810.9 mg of (η5-IC5H4)Re(CO)3 in 76% yield.

(η5-HC≡CC5H4)Re(CO)3

The synthesis of (η5-HC≡CC5H4)Re(CO)3 follows a method previously reported.49 (η5-IC5H4)Re(CO)3 (810.9 mg) was added to a flask under an argon atmosphere. To that, tributylethynylstannane (TBES, 551.7 mg) and DMF (33 mL) were added by syringe followed by the catalyst, (CH3CN)2PdCl2 (22.6 mg) in DMF (5 mL). The solution was stirred for 2 h. Ether (44 mL) and 50% aqueous KF (22 mL) were added to this solution. Argon was bubbled through the solution as it was stirred vigorously for 1 h. Ether extracts from the resulting solution were washed with water. The wash solution was back-extracted with ether. All ether extracts were dried over MgSO4 and filtered through diatomaceous earth. The solvent was removed by rotovap. The product was sublimated at 60 °C and 5 mTorr. The product was further purified over a silica column with n-hexanes to yield 299.9 mg (η5-HC≡CC5H4)Re(CO)3 (47.5%). IR (DMSO): νCO 1923.0 cm–1 as, 2020.4 cm–1 s. 1H NMR: (299.732 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.656 (Cp, t, J = 2.2 Hz, 4H), 5.285 (Cp, t, J = 2.2 Hz, 2H), 2.819 (−C≡CCH, s, 1H). 13C NMR: (75.375 MHz, CDCl3) δ 193.1 (CO), 88.7 (ipso-Cp), 84.0 (Cp), 83.9 (Cp), 77.9, 74.7. EI mass [M + Na]+ meas. 357.9764 m/z (calc. 357.9763 m/z).

Site-Specific Protein Labeling

CTL9-K109Aha was dissolved in labeling buffer, which consisted of 20 mM MOPS and 100 mM NaCl. Protein concentration was determined by absorbance at 280 nm. A stock solution of the metal carbonyl was prepared by dissolving the solid in DMSO to a concentration of 19 mM. Stock solutions of the labeling reagents were prepared as described by Hong et al.50 The solution consisted of 250 μM protein, 650 μM metal carbonyl, 200 μM CuSO4, 500 μM tris(3-hydroxypropyltriazolylmethyl)amine (THPTA), 5 mM sodium ascorbate, and 5 mM aminoguanidine in a volume of 1 mL. The pH of the reaction mixture was adjusted to 7.5. The reaction was run for 4 h at 37 °C with stirring and then quenched by the addition of 5 mM EDTA. Labeled protein was purified by reverse-phase HPLC on a C8 preparative column. An A-B gradient system was used, with buffer A composed of 0.045% (v/v) solution of hydrochloric acid (HCl) in water and buffer B composed of 90% (v/v) acetonitrile, 10% (v/v) water, and 0.045% (v/v) HCl. The gradient was 20–70% B in 100 min. The labeling efficiency was estimated by comparing the absorbance at 220 nm of the labeled and unlabeled proteins, which elute at different times. The purity of the labeled protein was examined by reverse-phase HPLC using a C18 analytical column.

Mass Spectroscopy

The protein probe complex, denoted CTL9-K109ReL1, was analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF). The expected m/z is 10 340.0, and the observed value is 10 339.6. A tryptic digest of CTL9-K109Aha was performed, and the peptide fragments were analyzed using liquid chromatography/time-of-flight mass spectrometry (LC–MS-TOF) to determine the percent incorporation of Aha. The UV signal at 215 nm was used for quantification. The percent incorporation was 91.6%.

NMR Spectroscopy

Protein samples were exchanged in D2O for 6–8 h at 37 °C then lyophilized. This process was repeated three times to ensure the amide proton exchange was complete. Wild-type CTL9 and CTL9-K109ReL1 were dissolved in a 100% D2O solution of 10 mM MOPS (pre-exchanged with D2O) and 150 mM NaCl at pD 6.6 (uncorrected pH reading). The protein concentration was ∼0.5 mM. 1D 1H NMR spectra were collected on a Bruker 500 MHz spectrometer. 0.5 mM DSS was used as an internal reference. The data were analyzed using the software package Mnova 7.

Equilibrium Denaturation

CD wavelength spectra and CD-monitored temperature denaturation experiments were performed on an Applied Photophysics Chirascan instrument. The protein was dissolved in a 10 mM MOPS, 150 mM NaCl solution for a final concentration of 15–20 μM. Measurements were made at pH 7.0 and 25 °C. Thermal denaturation data were fit to the following expression:

| 1 |

where Tm is the midpoint temperature, T is the temperature, ΔH°(Tm) is the change in enthalpy for the unfolding reaction at Tm, and ΔCpo is the change in heat capacity, which was set to 1.07 kcal·mol–1·deg–1, as determined by previous experiments.47

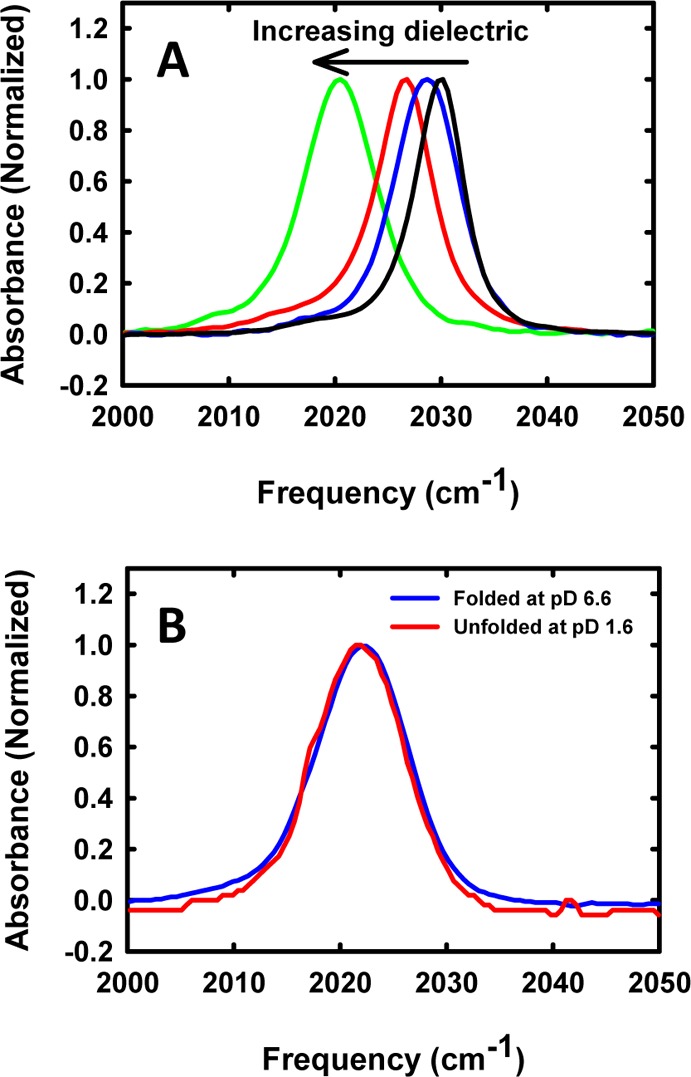

CD monitored urea denaturation experiments were performed on an AVIV 202SF spectrophotometer. Samples were 20 μM protein in 10 mM MOPS and 150 mM NaCl. Experiments were performed at pH 7.0 and 25 °C. The concentration of urea was determined by measuring the refractive index. Denaturation curves were fit to the equation

|

2 |

where

| 3 |

f is the ellipticity from CD-monitored denaturation experiments, ΔGuo is the change in free energy of unfolding, T is the temperature, and R is the gas constant. an is the intercept and bn is the slope of the curve in the pretransition region, while ad is the intercept and bd is the slope of the curve in the post-transition region.

FTIR Spectroscopy

FTIR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Tensor 27 FTIR spectrometer equipped with a liquid-nitrogen-cooled mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) detector. The spectra of the free metal carbonyl compound in various solvents were the result of 16 scans, and the concentration of compound was 1 mM. The protein spectra at pD 6.6 and pD 1.6 were the result of 256 scans, and the protein concentration was ∼300 μM. Spectra were recorded at a resolution of 1 cm–1 using a Bruker BioATR II cell. The effective path length of the cell was approximately 6–8 μm. All experiments were performed at 20 °C.

2D IR Spectroscopy

All samples were prepared in 10 mM MOPS and 150 mM NaCl in H2O at pH 7.0 or 10 mM dMOPS and 150 mM NaCl in D2O and measured at an 800 μM protein concentration. Femtosecond mid-IR pulses (∼1970 cm–1 center frequency, 200 cm–1 bandwidth) were generated as follows. The 800 nm output of a 2 kHz Ti:sapphire KMLabs Wyvern regenerative amplifier (3.2 mJ, 100 fs pulses) is used to pump a home-built optical parametric amplifier (OPA) followed by difference frequency generation to generate 4 μJ pulses of mid-IR light centered around 5 μm. The mid-IR light is split into pump (97%) and probe (3%) beams. The pump beam is sent to a pulse shaper, which creates pulse pairs with controlled time delays and phases on a shot-to-shot basis.51,52 The pulse delay was scanned from 0 to 4000 fs in 40 fs steps with a rotating frame frequency of 1850 cm–1. The output from the pulse shaper and the probe was focused onto the sample using a pair of off-axis parabolic mirrors. The waiting time was scanned using a motorized translation stage that incremented in steps of 500 fs to 1 ps. The probe pulse was detected on a 64-channel MCT array after passing through a monochromator.

Results and Discussion

Incorporation of Aha is well-documented, and incorporation levels on the order of 90 to 95% are often reported. The highest level of incorporation is desirable, but a modest fraction of protein containing Met instead of Aha can be tolerated, at least for single labeling applications, because the Met-containing protein will be spectroscopically silent if no label is bound. We obtained a 92% level of incorporation using the B834 E. coli strain with CTL9 under control of the lac operon, as judged by liquid chromatography/mass spectroscopy (Figure 1). This level of incorporation is far more than adequate for most applications, and if necessary unlabeled protein can be separated from labeled protein. In the example presented here, simple HPLC purification can be used to remove the small fraction of unlabeled protein. A clickable IR probe was prepared based on a rhenium metal carbonyl by modification of a protocol used to prepare methanethiosulfonate-modified tricarbonyl (η5-cyclopentadienyl) rhenium(I).27 In brief, the starting material, Re2(CO)10, was converted to CpRe(CO)3.33 The product was derivatized to (η5-HC≡CC5H4)Re(CO)3, as described by Stille and purified by flash column chromatography.49,53 The final product was characterized by NMR and EI mass spectrometry. The observed peaks agree with previously reported spectra.49,53 The metal carbonyl was incorporated using Cu(I) complexes with tris(3-hydroxypropyltriazolylmethyl) amine as the catalyst. Incorporation was quantitative, as judged by analytical HPLC (Supporting Information). This is an important consideration for bioorthogonal labeling approaches because it implies that the percentage of protein with a single label will be low.

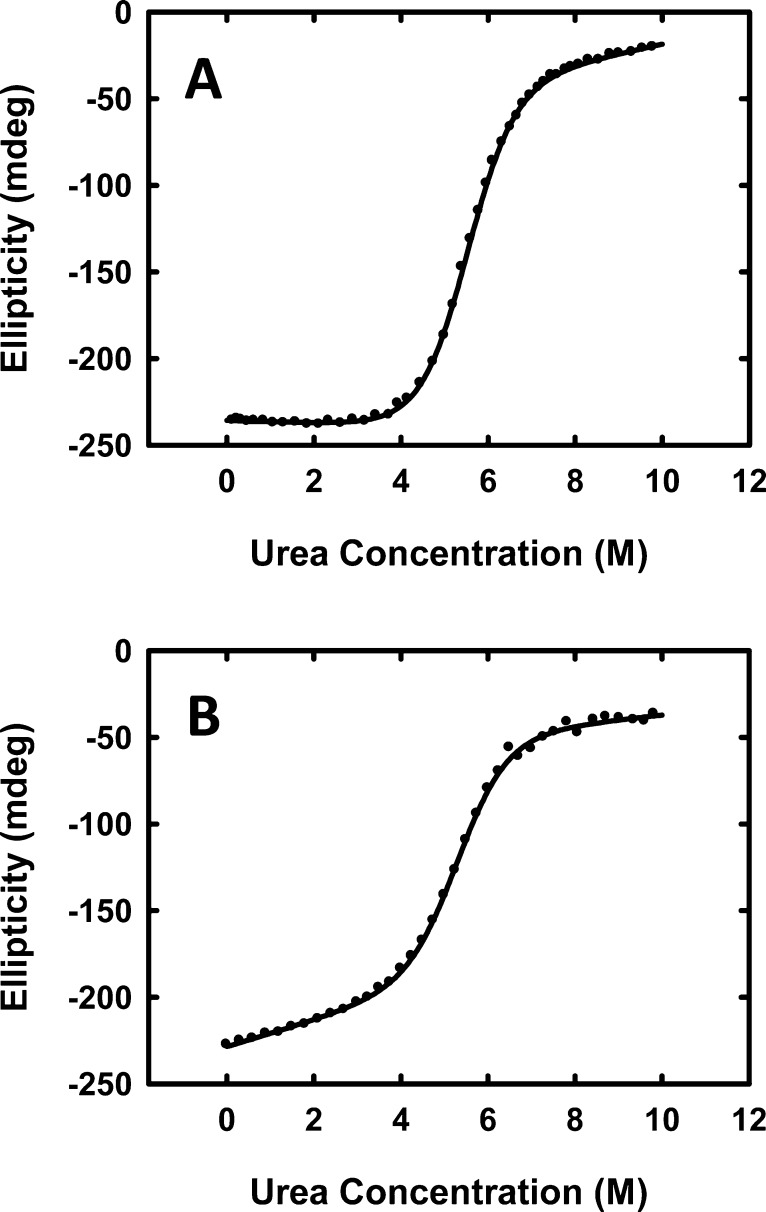

The probe does not perturb the structure of the protein as judged by CD and NMR, nor does it modulate the stability of the protein significantly. The CD spectra of wild-type CTL9 and labeled protein (denoted CTL9-K109ReL1) have essentially the same shape, and the 1H NMR spectra of both contain a set of distinctive aromatic resonances and ring-current-shifted methyl resonances, which are diagnostic of the folded state (Supporting Information). The free energies of unfolding for wild-type CTL9 and for the variant containing the probe (denoted CTL9-K109ReL1) are 6.00 ± 0.11 and 5.48 ± 0.27 kcal mol–1, respectively, as judged by urea-induced unfolding (Figure 2, Table 1). The two proteins also have similar m values, although the slopes of the pretransition baselines are slightly different (Table 1, Figure 2). The m value is believed to be related to the change in solvent-accessible surface area between the folded and unfolded states. The observation of similar m values is additional evidence that the probe is nonperturbing. The midpoint of the thermal unfolding transition was determined by CD-monitored unfolding and is similar for the two variants, as is the value of ΔH°. The close agreement between the values of ΔH° indicates that, as expected, the probe does not perturb the packing of the protein.

Figure 2.

Urea-induced unfolding experiments demonstrate that the probe does not significantly modify the stability of the protein. Urea-induced unfolding experiments were conducted by monitoring the CD signal at 222 nm. (A) Wild-type CTL9 and (B) metal carbonyl-labeled CTL9. The solid lines are the best fit to eq 2. Protein samples were in 10 mM MOPS, 150 mM NaCl at pH 7.0 at 25 °C. Protein concentration was 20 μM.

Table 1. Thermodynamic Parameters for Wild-Type CTL9 and K109ReL1-CTL9a.

| ΔG° (kcal mol–1) | m (kcal mol–1 M–1) | Tm (°C) | ΔH° (at 78 °C) (kcal mol–1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wild-type CTL9 | 6.00 ± 0.11 | 1.09 ± 0.02 | 78.1 ± 0.3 | 68.9 ± 2.0 |

| K109ReL1-CTL9 | 5.48 ± 0.27 | 1.03 ± 0.05 | 74.2 ± 0.2 | 65.4 ± 1.7 |

Measurements were made in 10 mM MOPS, 150 mM NaCl at pH 7.0.

The fact that the probe does not perturb the stability of the protein or the cooperativity of its folding, as judged by the m value for denaturant-induced unfolding and by ΔHo, is a significant observation. The metal carbonyl complex is very hydrophobic, and versions that are attached via long flexible linkers may potentially interact with nearby hydrophobic patches on the protein surface and could thus perturb protein stability and modulate protein ligand interactions, which rely on binding to hydrophobic regions.27 The Click reaction leads to a rigid triazole linkage that will help to project the probe away from the protein and thereby minimize potentially deleterious interactions with the protein surface.

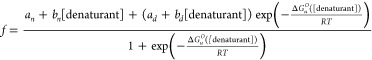

The frequency of the carbonyl vibrational mode of the metal complex is sensitive to the polarity of the environment, as illustrated in Figure 3A, which displays spectra of the compound recorded in several solvents. The absorption band shifts to a lower frequency as the solvent dielectric increases, moving from 2029.8 cm–1 with a full width at half-maximum (fwhm) of 4.7 cm–1 in 1:1 CH2Cl2/CCl4 to 2020.4 cm–1 with a fwhm of 6.6 cm–1 in DMSO (Table 2). The limited solubility of the unattached probe prevented measurements in H2O, but the frequency of the probe attached to the protein was 2021.8 cm–1 when the protein was unfolded. FTIR spectra were recorded for 300 μM samples of the labeled protein in both the folded and unfolded states. The site chosen for modification is exposed to solvent, and thus we expect that there should be little change in the peak position between the folded and unfolded states. This is indeed what we observed; the band is centered at 2022.0 cm–1 in the folded state and 2021.8 cm–1 in the acid unfolded state (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Frequency of the metal carbonyl probe is sensitive to environment. (A) FTIR spectra recorded in solvents with different dielectric constants: black, 1:1 CH2Cl2/CCl4; blue, isopropanol; red, acetonitrile; green, DMSO. (B) FTIR spectra of labeled CTL9 in (blue) the folded state and in the (red) acid unfolded state.

Table 2. Spectroscopic Properties of the Metal Carbonyl Probe in Solvents of Different Polarity.

| solvent | band position (cm–1) | fwhm (cm–1) | dielectric constant |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1:1 CH2Cl2/CCl4 | 2029.8 | 4.7 | 9.1, 2.2a |

| isopropanol | 2028.6 | 5.7 | 17.9 |

| acetonitrile | 2026.5 | 6.0 | 37.5 |

| DMSO | 2020.4 | 6.6 | 46.7 |

Dielectric constant of neat CH2Cl2 is 9.1 and that of neat CCl4 is 2.2.

Vibrational frequencies and lifetimes are often sensitive to their environment. Frequencies are largely determined by the polarity of their surroundings. The frequency of most stretch modes, like those studied here, are higher in low dielectric constant liquids than in high dielectric liquids. Lifetimes depend on internal couplings, external couplings, and frequency fluctuations caused by solvent and solute structural dynamics. Thus, to a first approximation, they are sensitive to different solvent effects, although dielectric constants and structural fluctuations often mirror one another.

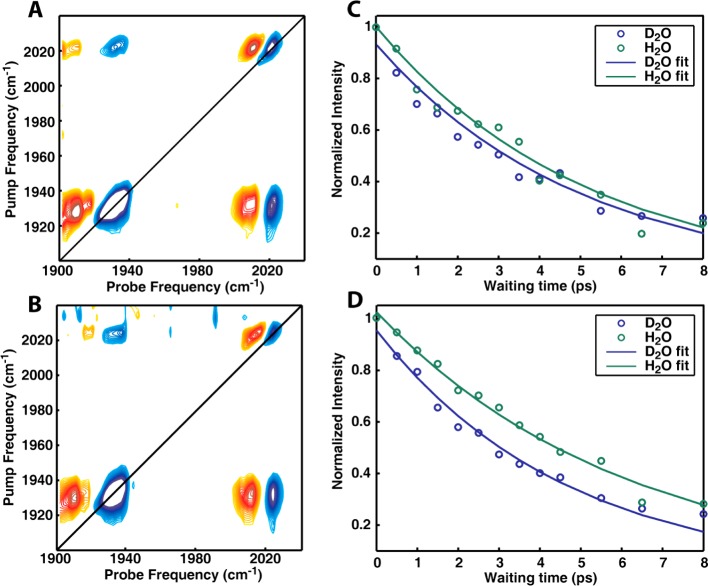

The FTIR spectra in Figure 3A are consistent with the expected trends, where the frequencies are higher in low dielectric constant liquids. We utilized 2D IR spectroscopy to examine the frequency and lifetime dependence of the metal carbonyl stretches in H2O and D2O. The 2D IR spectra can be interpreted in a similar manner to our previously published work that used a cysteine linkage to attach a metal carbonyl.27 Here we use 2D IR spectroscopy to measure the lifetimes. Results obtained from analysis of the diagonal peaks of the symmetric and asymmetric stretch modes are shown in Figure 4. Regarding the frequencies, a measurable 2 to 3 cm–1 frequency shift was observed, with asymmetric stretch frequencies of 1930 and 1932 cm–1 in H2O versus D2O, respectively, and symmetric stretch frequencies of 2021 and 2024 cm–1. Because the dielectric constants of H2O and D2O are 80.4 and 80.1, one would not expect a large frequency shift due to appreciable electrostatic interactions. This frequency shift may be a consequence of accidental degeneracies. In our previous work using a Cys linker, we adjusted the linker length and found that the frequencies reflected the electrostatics of the solvent for long linker lengths and reflected the environment of the protein for short linker lengths. For the Click chemistry used here, the linker is about the same length as our longest cysteine linker (if measured starting from the backbone, not the end of the methionine) and so should reflect the solvation dynamics of the protein.27 From a comparison with the control experiments, for residue 109 on CTL9, it is clear that the label is dominated by solvent effects in both the native and denatured forms, as expected from its solvent-exposed position in the native state.27,28

Figure 4.

Two-dimensional IR spectrum of the labeled protein. (A) 2D IR spectrum in H2O. (B) 2D IR spectrum in D2O. (C) Intensity of the diagonal peak of the symmetric stretch (circles) with single exponential fits (lines). (D) Intensity of the diagonal peak of the asymmetric stretch (circles) with single exponential fits (lines).

The lifetimes of the symmetric and asymmetric stretches also change when exposed to H2O versus D2O, as measured by monoexponential fits. The symmetric stretch lifetimes are 5.17 ± 0.64 and 5.04 ± 0.66 ps in H2O and D2O, respectively, and the asymmetric stretch lifetimes are 6.10 ± 0.48 and 4.66 ± 0.57 ps, respectively. This is a significant and easily measured difference. The solvent presumably changes the lifetime because of couplings and unexpected resonances. Kubarych et al. previously saw a similar 30% lifetime effect for a metal carbonyl complex; however, the lifetime was shorter in H2O, not D2O as observed here.54 This reversal is not unexpected because accidental degeneracies are very hard to predict. The two metal carbonyl complexes have very different structures and thus very different mode frequencies, making relaxation pathways for the two molecules difficult to anticipate. Nonetheless, it is clear that comparison of lifetimes in H2O and D2O provides a method to probe solvent accessibility.

Conclusions

In summary, we have presented a general method for the high-level incorporation of a metal carbonyl IR probe, which should be broadly applicable. The band position is sensitive to the environment, and solvent isotope effects can be exploited to interrogate accessibility. The ability to use the probe in conjunction with H2O and D2O isotope effects to probe the electrostatics and dynamics of the protein is very beneficial because the probe is easy to incorporate into proteins and is nonperturbative, maintaining the protein structure, at least when bound to the surface. The probe is likely to be more perturbing if introduced into the hydrophobic core of a protein, and this may limit some applications. The new methodology presented here complements strategies that target Cys side chains and is expected to facilitate IR-based investigations of protein ligand interactions and protein conformational changes as well as provide site-specific structural information.

An additional advantage of this class of probes is that the absorption bands are sharp, leading to the possibility of conducting multicolor experiments using different metal carbonyls. For example, one could attach a metal carbonyl of one sort to a cysteine and a different metal carbonyl via the Click reaction to a second site, thereby enabling structural and environmental probes at two sites simultaneously. Such a strategy could probe structure in a style similar to FRET or double electron–electron resonance (DEER) but with a shorter distance dependence.55 Of course, these labels are larger than native amino acids and some nongenetically encoded amino acids, and so they may alter protein stability if attached to sites in the interior of proteins. Nonetheless, they are similar in size or smaller than fluorescent or EPR probes, which have been widely used in the interior of proteins to measure solvent exposure and conformational changes.56 However, systematic studies have shown that small, seemingly conservative probes can perturb protein stability even when they do not perturb the overall fold.46,57,58 Of course, any potential effects on protein stability and structure can always be checked with standard assays such as the melting curves illustrated here. However, the utility of metal carbonyl vibrational labels is not in their relatively small size, but rather in their strong transition dipole strengths and environmental sensitivity, enabling studies at much lower protein concentrations and perhaps even 2D IR experiments in stained cells or tissues.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Bowu Luan for assistance with NMR Chuck Casey for the generous gift of Re2(CO)10, Teshik Yoon for purified THF, and Alex Clemens for assistance in vacuum-distilling DMF. We thank Siyeon Lee for providing the copper ligand. We thank Dr. Bela Ruzsicska for assistance with MS studies. This work was supported by grants from the NSF to D.P.R. (NSF MCB-1330259) and to I.C. (NSF CBET-0846259) and from the NIH to M.T.Z. (NIH DK79895). M.D.W. was partially supported by a GAANN fellowship from the DOE. T.O. acknowledges support from the NSF GRFP.

Supporting Information Available

HPLC data used to calculate the level of incorporation of the probe. CD and 1D NMR spectra of wild-type CTL9 and the metal carbonyl containing variant. Thermal unfolding curves for both proteins. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Hamm P.; Zanni M. T.. Concepts and Methods of 2D Infrared Spectroscopy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, U.K., 2011. [Google Scholar]

- DeCamp M. F.; DeFlores L.; McCracken J. M.; Tokmakoff A.; Kwac K.; Cho M. Amide I Vibrational Dynamics of N-Methylacetamide in Polar Solvents: The Role of Electrostatic Interactions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 11016–11026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waegele M. M.; Culik R. M.; Gai F. Site-Specific Spectroscopic Reporters of the Local Electric Field, Hydration, Structure, and Dynamics of Biomolecules. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 2598–2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.; Lee G.; Jeon J.; Cho M. Vibrational Spectroscopic Determination of Local Solvent Electric Field, Solute-Solvent Electrostatic Interaction Energy, and Their Fluctuation Amplitudes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J. T.; Ross M. R.; Kubarych K. J. Water-Assisted Vibrational Relaxation of a Metal Carbonyl Complex Studied with Ultrafast 2D-IR. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 3754–3759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greve C.; Preketes N. K.; Fidder H.; Costard R.; Koeppe B.; Heisler I. A.; Mukamel S.; Temps F.; Nibbering E. T. J.; Elsaesser T. N-H Stretching Excitations in Adenosine-Thymidine Base Pairs in Solution: Pair Geometries, Infrared Line Shapes, and Ultrafast Vibrational Dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 594–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.; Middleton C. T.; Zannni M. T.; Skinner J. L. Development and Validation of Transferable Amide I Vibrational Frequency Maps for Peptides. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 3713–3724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. S.; Shorb J. M.; Mukherjee P.; Zanni M. T.; Skinner J. L. Empirical Amide I Vibrational Frequency Map: Application to 2D-IR Line Shapes for Isotope-Edited Membrane Peptide Bundles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 592–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt J. R.; Corcelli S. A.; Skinner J. L. Ultrafast Vibrational Spectroscopy of Water and Aqueous N-Methylacetamide: Comparison of Different Electronic Structure/Molecular Dynamics Approaches. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 121, 8887–8896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho M. H. Coherent Two-Dimensional Optical Spectroscopy. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 1331–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naraharisetty S. R. G.; Kurochkin D. V.; Rubtsov I. V. C-D Modes as Structural Reporters via Dual-Frequency 2DIR Spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2007, 437, 262–266. [Google Scholar]

- Rubtsov I. V. Relaxation-Assisted Two-Dimensional Infrared (RA 2DIR) Method: Accessing Distances Over 10 Å and Measuring Bond Connectivity Patterns. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 1385–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schade M.; Moretto A.; Crisma M.; Toniolo C.; Hamm P. Vibrational Energy Transport in Peptide Helices after Excitation of C-D Modes in Leu-d10. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 13393–13397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woys A. M.; Lin Y. S.; Reddy A. S.; Xiong W.; de Pablo J. J.; Skinner J. L.; Zanni M. T. 2D IR Line Shapes Probe Ovispirin Peptide Conformation and Depth in Lipid Bilayers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 2832–2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nydegger M. W.; Rock W.; Cheatum C. M. 2D IR Spectroscopy of the C-D Stretching Vibration of the Deuterated Formic Acid Dimer. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 6098–6104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran S. D.; Woys A. M.; Buchanan L. E.; Bixby E.; Decatur S. M.; Zanni M. T. Two-Dimensional IR Spectroscopy and Segmental 13C Labeling Reveals the Domain Structure of Human γD-Crystallin Amyloid Fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 3329–3334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim S. H.; Gupta R.; Ling Y. L.; Strasfeld D. B.; Raleigh D. P.; Zanni M. T. Two-Dimensional IR Spectroscopy and Isotope Labeling Defines the Pathway of Amyloid Formation with Residue-Specific Resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106, 6614–6619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fafarman A. T.; Webb L. J.; Chuang J. I.; Boxer S. G. Site-Specific Conversion of Cysteine Thiols into Thiocyanate Creates an IR Probe for Electric Fields in Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 13356–13357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek P.; Mukherjee S.; Zanni M. T.; Raleigh D. P. Residue-Specific, Real-Time Characterization of Lag-Phase Species and Fibril Growth During Amyloid Formation: A Combined Fluorescence and IR Study of p-Cyanophenylalanine Analogs of Islet Amyloid Polypeptide. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 400, 878–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanek D. C.; Vorobyev D. Y.; Serrano A. L.; Gai F.; Hochstrasser R. M. The Two Dimensional Vibrational Echo of a Nitrile Probe of the Villin HP35 Protein. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 3311–3315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E. E.; Linderman B. Y.; Luskin A. C.; Brewer S. H. Probing Local Environments with the Infrared Probe: L-4-Nitrophenylalanine. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 2380–2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfieri K. N.; Vienneau A. R.; Londergan C. H. Using Infrared Spectroscopy of Cyanylated Cysteine To Map the Membrane Binding Structure and Orientation of the Hybrid Antimicrobial Peptide CM15. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 11097–11108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta S.; Li Y. L.; Rock W.; Houtman J. C. D.; Kohen A.; Cheatum C. M. 3-Picolyl Azide Adenine Dinucleotide as a Probe of Femtosecond to Picosecond Enzyme Dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 542–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. H.; Raleigh D.; Cho M. Azido Homoalanine is a Useful Infrared Probe for Monitoring Local Electrostatistics and Sidechain Solvation in Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 2158–2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye S. X.; Zaitseva E.; Caltabiano G.; Schertler G. F. X.; Sakmar T. P.; Deupi X.; Vogel R. Tracking G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Activation Using Genetically Encoded Infrared Probes. Nature 2010, 464, 1386–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye S. X.; Huber T.; Vogel R.; Sakmar T. P. FTIR Analysis of GPCR Activation Using Azido Probes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 397–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woys A. M.; Mukherjee S. S.; Skoff D. R.; Moran S. D.; Zanni M. T. A Strongly Absorbing Class of Non-Natural Labels for Probing Protein Electrostatics and Solvation with FTIR and 2D IR Spectroscopies. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 5009–5018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J. T.; Arthur E. J.; Brooks C. L.; Kubarych K. J. Site-Specific Hydration Dynamics of Globular Proteins and the Role of Constrained Water in Solvent Exchange with Amphiphilic Cosolvents. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 5604–5611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. K. K.; Tamimi A.; Fayer M. D. Dynamics in the Interior of AOT Lamellae Investigated with Two-Dimensional Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 5118–5126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treuffet J.; Kubarych K. J.; Lambry J. C.; Pilet E.; Masson J. B.; Martin J. L.; Vos M. H.; Joffre M.; Alexandrou A. Direct Observation of Ligand Transfer and Bond Formation in Cytochrome C Oxidase by Using Mid-Infrared Chirped-Pulse Upconversion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007, 104, 15705–15710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B. H.; Massari A. M. Origins of Spectral Broadening in Iodated Vaska’s Complex in Binary Solvent Mixtures. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 15741–15749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J. T.; Ross M. R.; Kubarych K. J. Ultrafast alpha-Like Relaxation of a Fragile Glass-Forming Liquid Measured Using Two-Dimensional Infrared Spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 157401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agbossou F.; Ramsden J. A.; Huang Y. H.; Arif A. M.; Gladysz J. A. Synthesis, Structure, and Reactivity of (Pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)rhenium Aldehyde Complexes [(.eta.5-C5Me5)Re(NO)(PPh3)(.eta.2-O:CHR)]+BF4-: Highly Diastereoselective Deuteride Additions. Organometallics 1992, 11, 693–701. [Google Scholar]

- Jo H.; Culik R. M.; Korendovych I. V.; DeGrado W. F.; Gai F. Selective Incorporation of Nitrile-Based Infrared Probes into Proteins via Cysteine Alkylation. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 10354–10356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grechko M.; Zanni M. T. Quantification of Transition Dipole Strengths using 1D and 2D Spectroscopy for the Identification of Molecular Structures via Exciton Delocalization: Application to Alpha-Helices. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 137, 184202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolf B.; Palusiak M.; Zakrzewski J.; Salmain M.; Jaouen G. Sulfhydryl-Selective, Covalent Labeling of Biomolecules with Transition Metallocarbonyl Complexes. Synthesis of (eta5-C5H5)M(CO)3(eta1-N-maleimidato) (M = Mo, W), X-ray Structure, and Reactivity Studies. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005, 16, 1218–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jao C. C.; Hegde B. G.; Chen J.; Haworth I. S.; Langen R. Structure of Membrane-Bound Alpha-Synuclein from Site-Directed Spin Labeling and Computational Refinement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 19666–19671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmain M.; Jaouen G. Side-Chain Selective and Covalent Labelling of Proteins with Transition Organometallic Complexes. Perspectives in Biology. C. R. Chim. 2003, 6, 249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Rodriguez A. M.; Busby M.; Gradinaru C.; Crane B. R.; Di Bilio A. J.; Matousek P.; Towrie M.; Leigh B. S.; Richards J. H.; Vlcek A. Jr.; Gray H. B. Excited-State Dynamics of Structurally Characterized [ReI(CO)3(phen)(HisX)]+ (X = 83, 109) Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Azurins in Aqueous Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 4365–4370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren J. J.; Ener M. E.; Vlcek A. Jr.; Winkler J. R.; Gray H. B. Electron Hopping Through Proteins. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 2478–2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haquette P.; Salmain M.; Svedlung K.; Martel A.; Rudolf B.; Zakrzewski J.; Cordier S.; Roisnel T.; Fosse C.; Jaouen G. Cysteine-Specific, Covalent Anchoring of Transition Organometallic Complexes to the Protein Papain from Carica Papaya. ChemBioChem. 2007, 8, 224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binkley S. L.; Leeper T. C.; Rowlett R. S.; Herrick R. S.; Ziegler C. J. Re(CO)(3)(H(2)O)(3)(+) Binding to Lysozyme: Structure and Reactivity. Metallomics 2011, 3, 909–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Silva T.; Mukhopadhyay A.; Seixas J. D.; Bernardes G. J.; Romao C. C.; Romao M. J. CORM-3 Reactivity Toward Proteins: The Crystal Structure of a Ru(II) Dicarbonyl-Lysozyme Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 1192–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiick K. L.; Saxon E.; Tirrell D. A.; Bertozzi C. R. Incorporation of Azides into Recombinant Proteins for Chemoselective Modification by the Staudinger Ligation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A.; Nairn N. W.; Johnson R. S.; Tirrell D. A.; Grabstein K. Processing of N-terminal Unnatural Amino Acids in Recombinant Human Interferon-β in Escherichia coli. ChemBioChem 2008, 9, 324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taskent-Sezgin H.; Chung J. A.; Banerjee P. S.; Nagarajan S.; Dyer R. B.; Carrico I.; Raleigh D. P. Azidohomoalanine: A Conformationally Sensitive IR Probe of Protein Folding, Protein Structure, and Electrostatics. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 7473–7475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S.; Raleigh D. P. pH-dependent Stability and Folding Kinetics of a Protein with an Unusual α-β Topology: The C-terminal Domain of the Ribosomal Protein L9. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 318, 571–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Gupta R.; Cho J. H.; Raleigh D. P. Mutational Analysis of the Folding Transition State of the C-terminal Domain of Ribosomal Protein L9: A Protein with an Unusual β-Sheet Topology. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 1013–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipperfield A. K.; Housecroft C. E.; Rheingold A. L. Synthesis and Characterization of Tetraruthenaborane Clusters - Molecular-Structure of [HRu4(CO)12Au2(PPh3)2B]. Organometallics 1990, 9, 681–687. [Google Scholar]

- Hong V.; Presolski S. I.; Ma C.; Finn M. G. Analysis and Optimization of Copper-Catalyzed Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition for Bioconjugation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9879–9883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim S. H.; Strasfeld D. B.; Zanni M. T. Generation and Characterization of Phase and Amplitude Shaped Femtosecond Mid-IR Pulses. Opt. Express 2006, 14, 13120–13130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim S. H.; Strasfeld D. B.; Fulmer E. C.; Zanni M. T. Femtosecond Pulse Shaping Directly in the Mid-IR Using Acousto-Optic Modulation. Opt. Lett. 2006, 31, 838–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losterzo C.; Miller M. M.; Stille J. K. Use of Palladium-Catalyzed Coupling Reaction in Synthesis of Homobimetallic Dimers: Preparation of [Bis(cyclopentadienyl)acetylene]metal Complexes and their Reaction with Dicobalt Octacarbonyl. Evidence For Formation of Dihydrido Species in Diiron Complexes. Organometallics 1989, 8, 2331–2337. [Google Scholar]

- King J. T.; Ross M. R.; Kubarych K. J. Water-Assisted Vibrational Relaxation of a Metal Carbonyl Complex Studied with Ultrafast 2D-IR. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 3754–3759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleissner M. R.; Brustad E. M.; Kalai T.; Altenbach C.; Cascio D.; Peters F. B.; Hideg K.; Peuker S.; Schultz P. G.; Hubbell W. L. Site-Directed Spin Labeling of a Genetically Encoded Unnatural Amino Acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106, 21637–21642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain S.; Franck J. M.; Han S. Transmembrane Protein Activation Refined by Site-Specific Hydration Dynamics. Angew. Chem. 2013, 52, 1953–1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikary R.; Zimmermann J.; Dawson P. E.; Romesberg F. E. IR Probes of Protein Microenvironments: Utility and Potential for Perturbation. ChemPhysChem 2014, 15, 849–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann J.; Thielges M. C.; Seo Y. J.; Dawson P. E.; Romesberg F. E. Cyano Groups as Probes of Protein Microenvironments and Dynamics. Angew. Chem. 2011, 50, 8333–8337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.