Abstract

Abdominal wall endometriosis (AWE) is a rare condition that usually develops in a surgical scar resulting from a Caesarean section. While commonly seen in the cutaneous and subcutaneous fat tissue at the Caesarean scar level, its intramuscular localization is quite rare. Its treatment options consist of the excision of the lesion and/or hormonal therapies, although wide surgical excision is the treatment of choice in the literature. Wide surgical excision may create a defect in the abdominal wall and may increase the risk of hernia formation and mesh complications. This case report describes the clinical and radiological findings and treatment modalities of endometriosis that have appeared in the rectus abdominis muscle of a 25-year-old patient at the Caesarean scar level. Sclerotherapy may be used for endometrioma. We present a new and alternative treatment method using ultrasound-guided intralesional ethanol injection for AWE. Compared with the complications of surgical excision, the complications of sclerotherapy by ethanol are at a more acceptable level. Sclerotherapy by ethanol injection may be an alternative treatment to surgery for AWE.

Keywords: Abdominal wall, Endometriosis, Fine needle aspiration cytology, Intramuscular endometriosis, Magnetic resonance imaging, Sclerotherapies

Endometriosis is described as the presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity. Endometriosis is most commonly located in the ovaries, bowel, or the tissue lining in the pelvis. It may develop in virtually every organ in extrapelvic sites. The abdominal wall is an uncommon site of the extrapelvic location, where it mostly occurs in an old surgical scar. Abdominal wall endometriosis (AWE) appears following the implantation of endometrial cells into the soft tissues of the abdominal wall after open uterine surgeries like Caesarean sections. The incidence rate is reported at 0.4% to 0.1%.1 The disease is characterized with the triad of mass in the abdominal wall, periodic pain associated with menses, and history of abdominal surgery. Its treatment is recognized to be broad surgical excision. There are reports suggesting that successful results can be achieved in patients with pelvic endometriosis by injecting ultrasound-guided alcohol into the lesion and performing sclerotherapy as well as surgical treatment.2,3 However, to the best of our knowledge, the literature contains no cases of intramuscular AWE treated by injecting ultrasound-guided alcohol. This case report describes the clinical and radiological findings of a patient who had intramuscular AWE following Caesarean section and received sclerotherapy by injecting ultrasound-guided alcohol.

Case Report

We report a 25-year-old female patient (G2 P2 A0 C0) who underwent a Caesarean section 7 years ago for post-term pregnancy with no response to induction. The patient, who underwent a second Caesarean section 4 years ago, was admitted to another clinic 26 months after this operation with complaints of pain in the Caesarean scar and a palpable mass in the anterior wall of the abdomen. Hematoma in the rectus abdominis muscle was suspected on computed tomography and ultrasound scans, and palliative treatments were performed at other hospitals. The patient’s complaints were not resolved with medical treatment, and she was admitted to the Clinic of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Universal Malatya Hospital with complaints of increased pain and increase in mass size. The patient stated that the pain was cyclic, intensified particularly in the first 2 days of menstruation, and it significantly restricted her daily activities. She had no history of chronic diseases, previous ovarian cyst surgeries, or endometriosis. The gynecological examination was normal. Routine laboratory findings were in the normal range. Abdominal examination showed a hard and partially mobile, painful, and palpable mass lesion, about 3 cm × 1.5 cm, located in the right side of the Caesarean scar.

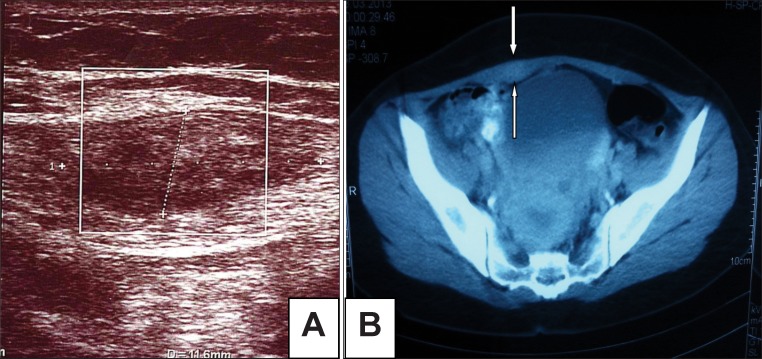

Ultrasound was performed with LOGIQ 9 ultrasound system (GE Healthcare Technologies, Milwaukee, WI, USA) by using linear (12–14 MHz) and convex (2–5 Mhz) transducers. Superficial ultrasound scan showed a heterogeneous hypoechoic, irregularly marginated lesion, 30 mm ×14 mm, in the lower right quadrant in the rectus abdominis muscle (figure 1A). The patient’s contrast enhanced abdominal computed tomography scan taken at another hospital showed an asymmetrical thickening at the inferior portion of the left rectus abdominis muscle and a hyper-intense mass, suggestive of hematoma (figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) A heterogeneous hypoechoic appearance in the rectus abdominis muscle in the transverse plane in the ultrasound. (B) An asymmetrical thickening compared with the left at the inferior of the rectus abdominis muscle as well as a hypertensive state that would suggest hemorrhage.

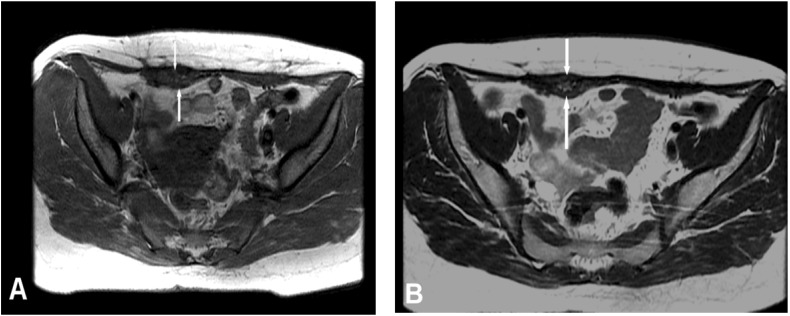

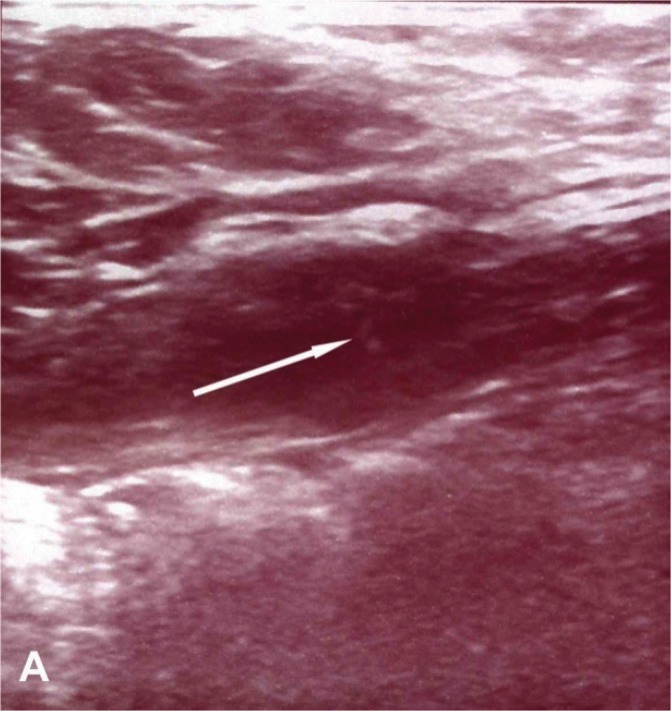

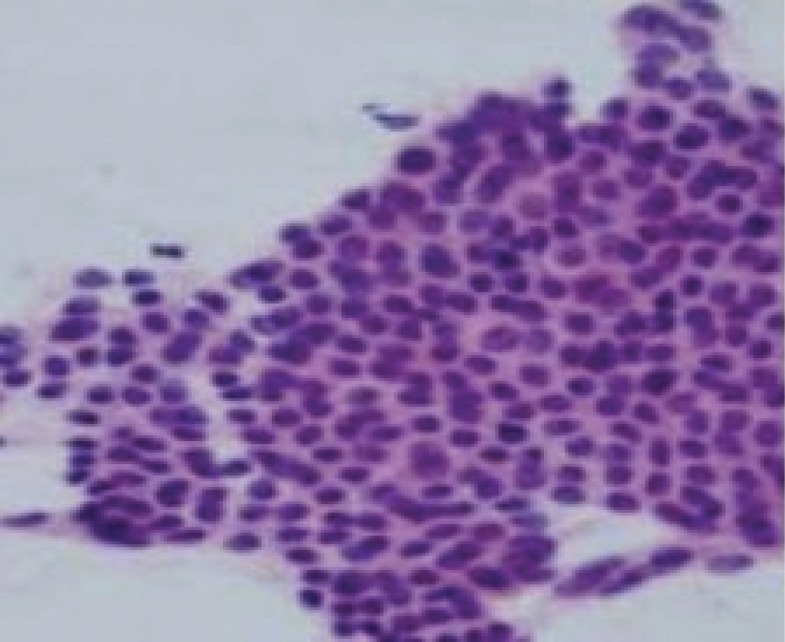

Lower abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed on the patient with a 1.5-Tesla MR device (General Electric SignaExcita, GE Health Care System, Milwaukee, WI, USA). The scan protocol included axial T1 fast spin echo, axial and sagittal T2-weighted fast spin echo sequences, axial and coronal fat saturated proton density sequences, diffusion weighted axial sequences, and pre- and post-contrast axial and coronal T1-weighted fast spoiled gradient-echo fat-suppressed sequences. MRI imaging showed a weakly contrasting mass, 3 cm × 1.5 cm, containing heterogeneous hypo-hyperintense areas in the suprapubic region on the right rectus abdominis muscle in the T1 and T2A sequences, causing asymmetric thickening (figure 2). Diffusion-weighted images showed a slight signal increase secondary to restricted diffusion in the mass. Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values were found to be 0.95×10−3 mm2/sn. Given these findings, aspiration biopsy was performed on the patient with ultrasound, considering AWE as a differential diagnosis. The patient was diagnosed with intramuscular AWE after observing the endometrial glands, stroma, and smooth muscle cells following post-biopsy microscopic analysis. Sclerotherapy, by injection of alcohol into the patient’s lesion, was planned as treatment. Approval was obtained from the patient and the hospital’s ethics committee. After local anesthesia of 1 cc 95% ethanol was injected with ultrasound guidance into various parts of the lesion using a 22 gauge needle (figure 3). After the procedure, pelvic ultrasound and pelvic MRI were performed to check for any complications. Fine needle aspiration cytology confirmed the endometriosis. In the cytology, the epithelial clusters showed orderly spaced nuclei arranged in a honeycomb pattern (figure 4). Oral contraceptives were started for 3 months to reduce the risk of recurrence. Three months later, hormonal treatment was stopped, followed by an additional 3-month follow-up. The patient reported that her pain completely disappeared during the 9-month follow-up, and no recurrence was observed.

Figure 2.

(A,B) Fast spin echo T1 and T2-weighted axial, (C) coronal fat saturated proton density, (D) mass lesion with asymmetric thickening in right rectus abdominis muscle and a heterogeneous intramuscular hypo-hyperintense signal pattern in fast spin echo T2 sagittal images (arrows).

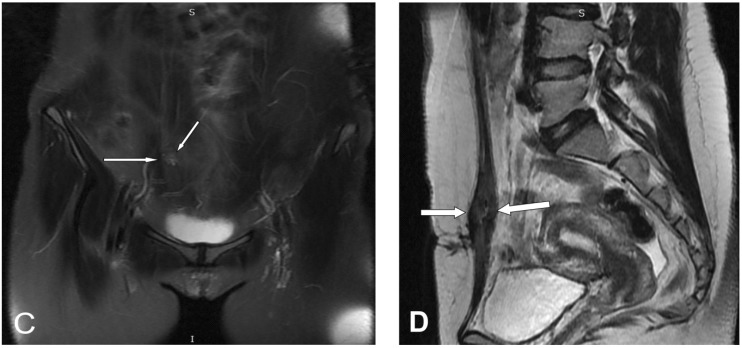

Figure 3.

(A) Needle echogenicity is noticeable in the endometriosis focus in the rectus muscle and at the center of the lesion (arrow) immediately before ethanol injection.

Figure 4.

Fine needle aspiration findings of endometriosis of abdominal wall. The epithelial clusters showing orderly spaced nuclei arranged in honeycomb pattern (pap-stain ×20).

Discussion

The abdominal wall is an uncommon site of extrapelvic endometriosis, where it usually develops within the skin or subcutaneous tissues of the abdominal wall. Endometriosis involving the rectus abdominis muscle is rare. The differential diagnosis of rectus abdominis muscle mass lesions includes hernias, lipomas, hematomas, abscesses, and benign as well as malignant tumors.4 Most abdominal wall endometriosis is located in old surgical scars resulting from invasive abdominal-pelvic surgery. The etiology of these foci of endometriosis is thought to be an iatrogenic transfer of endometrial cells into the surgical or procedural wound.5

The literature mostly contains single case reports or case series about abdominal wall endometriosis. A study conducted on 445 patients reported that the most important clinical finding in abdominal wall endometriosis was palpable mass, located particularly on the corners at the level of the Caesarean scar, and this finding was accompanied by a prevalence rate of 96%. In 86% of the patients, pain was described as the main symptom, with a cyclic characteristic in more than half of them (57%). The mean time between clinical presentation and surgery was found to be 3.6 years.4 A retrospective study with 33 patients by Leite et al6 reported that endometriosis incidence caused by Caesarean scar was 0.29%, and endometriosis incidence caused by episiotomy scar after vaginal delivery was 0.01%. It should be noted that pain cannot be cyclic at all times. It has even been reported that non-cyclical pain was seen more commonly in certain series. The main symptom (pain) has been reported to be cyclic at a rate of 66.7%. Caesarean section has been reported to be the major risk factor in abdominal wall endometriosis, and it has been observed that a previous Caesarean section increased the relative risk of AWE by 27 times.6,7 The palpated painful mass in our case was screened on the right side of the Caesarean scar. The pain was cyclic and increased during menstruation, particularly in the first 2 days, significantly reducing the patient’s daily activities. The time between previous Cesarean section and clinical symptoms was 2.1 years.

Despite the use of ultrasound, CT, and MRI for the diagnosis of endometriosis, there were no pathognomonic imaging findings for endometriosis. Its appearance depends on the stage of the menstrual cycle, the proportion of stromal and glandular elements, the amount of bleeding, and the degree of surrounding inflammatory and fibrotic response. Due to these non-specific findings, a wide spectrum of disorders such as hernias, lipomas, hematomas, abscesses, and benign and malignant tumors presenting as a mass lesion in the abdominal wall should be considered in the radiological differential diagnosis.8 In our case, ultrasound showed an irregularly marginated intramuscular lesion with a heterogeneous echogenicity. The lesion could not be clearly distinguished from the scar tissue, mass, or chronic period hematoma. The CT scan showed hypertensive areas, suggesting hemorrhage in the lesion. Mass hematoma could not be clearly distinguished. Reports in the literature describe several kinds of signal patterns seen in endometrioma using MRI imaging in AWE, due to the different stage of blood products found within these implants. In these studies, endometriosis appeared homogeneously hypointense or isointense, or heterogeneous with focal areas of high and low signal intensity, suggesting old hemorrhage or fibrosis on T2-weighted and T1-weighted fat-suppressed imaging. Recent developments in MRI make it possible to obtain reliable diffusion-weighted images of the abdomen. Diffusion MRI is a method that allows for the mapping of the diffusion process of molecules, mainly water, in biological tissues. Water molecule diffusion patterns can reveal microscopic details about tissue architecture, either normal or in a diseased state. Several studies have shown that diffusion-weighted imaging may be useful for differentiating tumors according to their different cellular construction.8,9 Regarding endometriotic cysts (endometrioma), previous studies found a tendency towards lower ADC values compared with other pelvic cysts, which might be more closely related to blood concentration.10

In our case, MRI showed lesions consistent with hemorrhage and fibrosis, containing heterogeneous hypo-hyperintense areas on the rectus abdominis muscle in the T1 and T2-weighted sequences. Weak contrast enhancement was observed in the lesion after injection of contrast material. There was increased signal intensity due to restricted diffusion in DW sequences, with ADC values measured at 0.95×10−3 mm2/sn.

Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration can be a useful and less invasive method to confirm abdominal wall endometriosis. The sample may show tubular structures that are indicative of endometrial tissue and stromal cells to confirm the diagnosis of the endometriosis.9 Despite extremely rare reports of malignant degeneration, ruling out malignancy and allowing for a quick diagnosis are the other important features of fine needle aspiration.11,12

Hormonal therapy and surgical excision are routinely used in the treatment of AWE. Hormonal treatment offers temporary alleviation of symptoms, but recurrence is common after cessation of treatment.13 The recurrence rate after surgery reported in the previous studies is 4.3%.4 To avoid recurrence, wide excision is recommended. The size of the lesion and extent of the mass, especially when it involves the rectus abdominis muscle or peritoneum, have shown to be risk factors for recurrence.14 Literature review revealed no studies reporting the incidence of recurrence in AWE patients treated with ethanol injection.

In wide surgical resections, complications including foreign substance reactions, mesh migration, and eventual incidence of hernia may appear due to the propylene mesh used.14 In the literature, abdominoplasty with polypropylene mesh was recommended for abdominal wall reconstruction in large lesions to reduce hernia development.14

A review of the literature revealed several studies that reported positive findings after injecting 95% ethanol into the endometrioma in patients with pelvic endometriosis.15,16 With this in mind, we planned sclerotherapy by ultrasound-guided ethanol to our patient with intramuscular AWE. The patient’s pain completely disappeared after the treatment, and there was no recurrence during the 9-month follow-up. We believe that the major factors in such a successful treatment were the absence of a large endometriosis focus (3×1.5 cm), its occurrence only in the muscles, and lack of an intraperitoneal extension. Intralesional ethanol injection may result in difficult-to-repair necrosis on the anterior muscles of the abdominal wall in large lesions. Also, in endometriosis foci extending into the intraperitoneal region, it may cause complications including chemical peritonitis and severe pain as a result of alcohol penetration into the peritoneum. In such patients, therefore, injections may be given in several sessions instead of a single session. Compared with the complications of surgical excision, the complications of sclerotherapy by ethanol are at a more acceptable level. So, sclerotherapy by ethanol injection before surgical resection may be used as the first option in treatment.

AWE incidence also increases in association with increased numbers of Caesarean sections. Minimizing the contact of swabs used to clean the endometrial cavity within the scar site, quickly removing them from the operation area, avoiding the use of suture material that was used to close the uterus in order to suture the scar site, and thoroughly washing the scar site with saline before closing it are recommended to prevent the growth of endometriotic focus from the scar tissue. No prospective studies are available on this subject.

In conclusion, if a previous surgical history exists in cases with no primary pelvic endometriosis, endometriosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of the palpable abdominal anterior wall masses at the scar site. Although excision is the conventional treatment in abdominal wall endometriosis, care should be taken for potential post-surgical complications. Sclerotherapy used for endometriotic cysts has been reserved for those patients who have high surgical risk, are pregnant, or refuse surgical intervention. In the literature ultrasound-guided aspiration and sclerotherapy with 95% ethanol provides a valid alternative to surgery in treating endometrial cysts.17 Contrary to conventional treatments, the patients’ complaints are eliminated by sclerotherapy with ultrasound-guided ethanol injection into the lesion, a minimally invasive method, and an accompanying short-term hormonal treatment, and no recurrence in the short term. Injection of 95% ethanol into the intra-abdominal endometriosis may be an alternative method to surgery. To our knowledge, this is the first case in the literature to report the success of this condition. Further investigations of large series are needed to compare the surgical operation with ethanol injection treatment.

References

- 1.Balleyguier C, Chapron C, Chopin N, Hélénon O, Menu Y. Abdominal wall and surgical scar endometriosis: results of magnetic resonance imaging. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2003; 55: 220–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noma J, Yoshida N. Efficacy of ethanol sclerotherapy for ovarian endometriomas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2001; 72:35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsieh CL, Shiau CS, Lo LM, Hsieh TT, Chang MY. Effectiveness of ultrasound-guided aspiration and sclerotherapy with 95% ethanol for treatment of recurrent ovarian endometriomas. Fertil Steril 2009;91:2709–2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horton JD, Dezee KJ, Ahnfeldt EP, Wagner M. Abdominal wall endometriosis: a surgeon’s perspective and review of 445 cases. Am J Surg 2008;196:207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodward PJ, Sohaey R, Mezzetti TP., Jr Endometriosis: radiologic- pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2001;21:193–216; questionnaire 288–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leite GK, Carvalho LF, Korkes H, Guazzelli TF, Kenj G, Viana Ade T. Scar endometrioma following obstetric surgical incisions: retrospective study on 33 cases and review of the literature. Sao Paulo Med J 2009;127:270–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bektaş H, Bilsel Y, Sari YS, Ersöz F, Koç O, Deniz M, Boran B, Huq GE. Abdominal wall endometrioma; a 10-year experience and brief review of the literature. J Surg Res 2010;164:77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Onbas O, Kantarci M, Alper F, Kumtepe Y, Durur I, Ingec M, Gursan N, Okur A. Nodular endometriosis: dynamic MR imaging. Abdom Imaging 2007;32:451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamashita Y, Tang Y, Takahashi M. Ultrafast MR imaging of the abdomen: echo planar imaging and diffusion-weighted imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 1998;8:367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Busard MP, Mijatovic V, van Kuijk C, Hompes PG, van Waesberghe JH. Appearance of abdominal wall endometriosis on MR imaging. Eur Radiol 2010;20:1267–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pathan SK, Kapila K, Haji BE, Mallik MK, Al- Ansary TA, George SS, Das DK, Francis IM. Cytomorphological spectrum in scar endometriosis: a study of eight cases. Cytopathology 2005;16:94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chene G, Darcha C, Dechelotte P, Mage G, Canis M. Malignant degeneration of perineal endometriosis in episiotomy scar, case report and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2007;17:709–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bats AS, Zafrani Y, Pautier P, Duvillard P, Morice P. Malignant transformation of abdominal wall endometriosis to clear cell carcinoma: case report and review of the literature. Fertil Steril 2008;90:1197.e13–1197.e16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pados G, Tympanidis J, Zafrakas M, Athanatos D, Bontis JN. Ultrasound and MR-imaging in preoperative evaluation of two rare cases of scar endometriosis. Cases J 2008;1:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins AM, Power KT, Gaughan B, Hill AD, Kneafsey B. Abdominal wall reconstruction for a large caesarean scar endometrioma. Surgeon 2009;7:252–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matter M, Schneider N, McKee T. Cystadenocarcinoma of the abdominal wall following caesarean section: case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol 2003;91:438–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gatta G, Parlato V, Di Grezia G, Porto A, Cappabianca S, Grassi R, Rotondo A. Ultrasound-guided aspiration and ethanol sclerotherapy for treating endometrial cysts. Radiol Med 2010;115:1330–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]