Abstract

Reconstruction of tendons following complex trauma to the upper limb presents unique clinical and research challenges. In this article, the authors review the principles guiding preoperative assessment, surgical reconstruction, and postoperative rehabilitation and management of the upper extremity. Tissue engineering approaches to address tissue shortages for tendon reconstruction are also discussed.

Keywords: hand surgery, staged reconstruction, complex trauma, tissue engineering

According to the 2013 National Trauma Data Bank Annual Report, 29.77% of all trauma patients in the United States sustained injuries to the upper limb.1 In the most complex of these cases, limb salvage can be difficult in its own right, and tendon reconstruction presents a unique set of problems to the reconstructive hand surgeon.2 3 Attempts at tendon reconstruction can result in variable functional outcomes with considerable socioeconomic and psychological consequences.4 In these patients, it is accepted that bony stability and well-vascularized tissue coverage are the first considerations, but anatomical complexity, aesthetic and functional considerations, and concomitant life-threatening injuries present unique reconstructive challenges. Arguably, the most difficult task is tendon reconstruction because of the need to re-establish not only tendon continuity, but also gliding environments and surrounding structures with restoration of prehension. Thus, the difficulty of tendon reconstruction in complex injuries is commonly underestimated by both surgeons and patients. In this article, an approach to this problem is outlined with a focus on delayed flexor tendon reconstructive techniques and their preferred methodology using illustrative cases.

Unsolved Problems and Complications in Tendon Reconstruction

The most significant challenge in flexor tendon reconstruction is the lack of sufficient donor tendon materials for grafting and flexor tendon adhesions following surgery.5 Although palmaris, plantaris longus, and toe extensor tendon autografts are commonly used, the tissue required often far exceeds availability in the most complex and devastating injuries. Adhesions, first defined by Potenza in 1963, are caused by several variables including the site and type of injury, the surgical technique, and the nature of the wound healing response, and they are by far the most common complication following reconstruction.6 7 8 This is most prevalent in zone II injuries, in which both deep and superficial flexor tendons glide in a tight fibro-osseous tunnel. Canine research has demonstrated intrasynovial tendons display intratendinous neovascularization rather than the peripheral vascular adhesions seen with extrasynovial tendons, which translates to better functionality in intrasynovial grafts.9 This suggests that intrasynovial tendons undergo intrinsic healing, whereas extrasynovial tendons are dependent on peripheral neovascularization, which promotes adhesions. This knowledge has not translated into clinical practice in managing complex injuries due to donor site morbidity and a lack of accessible donor intrasynovial tendons.

Cadaveric allograft tendons may be a rare alternative option for grafts when the patient either does not want an autograft or when the need for tendon autografts exceeds supply. Peacock proposed a method in 1971 to harvest the finger flexor tendons and fibro-osseous sheath as a composite graft from a human cadaver and perform the reconstruction in a single surgery.10 However, this technique faces the same drawbacks as any allogeneic transplant, such as potential for disease transmission and need for immunosuppression though to a lesser extent than other tissue types due to the sparse cellularity of tendons.

These challenges have stimulated exploration of alternative graft sources. Synthetic tendon composed of silastic sheets and Dacron have so far been inferior to human tendon in terms of postoperative strength and healing.11 12 Over the past few years, significant progress has been made in engineering decellularized cadaveric flexor tendon allografts, as is discussed in the New Directions section below. Yet, Tang and colleagues have shown promising results with tendon allografts that were sterilized and preserved by deep-freezing without decellularization.13 A pilot study in 22 patients showed that this technique resulted in functional outcomes comparable to autografting and did not produce an immunogenic reaction.

Complications of tendon reconstruction include proximal and distal interphalangeal joint stiffness and volar-based contractures frequently related to overly aggressive postoperative splinting, pulley failure with resultant bowstringing, repair ruptures, triggering, lumbrical plus deformities, and quadriga phenomena. Patients with heavily contaminated wounds, concomitant thermal or chemical injuries, or coexisting fractures or crush injuries have a marked increased risk of infection.14 15 16 These complications invariably result in suboptimal functional outcomes.

Assessment

The hand and upper limb are easily at risk of injury in the setting of industry, the home, assault, and motor vehicle incidents. Mangling or mutilating trauma is commonly encountered as increasing mechanization in society presents heightened risk. The most complex injuries occur following high-energy trauma and are often associated with other life-threatening injuries. Thus, one should initially adhere to the life before limb philosophy before contemplating any intervention using advanced trauma life support (ATLS) guidelines with resuscitation and management of life threatening injuries taking priority.17 18 19 Such injuries are often composite, involving combinations of soft, osseous, vascular, and neural tissue. Although ideal treatment goals remain limb salvage and maximum functional outcome, these injuries carry a high potential for morbidity and amputation. Several scoring systems have been devised to assist in the surgical decision-making process in lower limb salvage, but only a few for the upper limb.14 20 21 22 23 24 25 These systems are difficult to use when deciding on the definitive treatment of a complex upper extremity injury involving tendinous tissue loss, as they are often arbitrarily grouped to the part of the hand involved or tissue type lost and are not designed to predict functional outcome.26 27 28 29

Moreover, compared with the lower limb, upper limb salvage is much preferred to amputation and fitting of prostheses. Due to the unique prehension of the hand, prostheses are intrinsically less functional than leg prosthetics, and the patient may prefer to use their own “bad” hand rather than a “good” prosthetic. Furthermore, 30 to 79% of upper limb amputees face chronic pain and phantom limb syndrome.19 The upper limb is also more amenable to salvage because it has less muscle mass and is thus less susceptible to crush syndrome. Symmetry of limb length is much less of a consideration because the upper extremity is not used to walk. For patients, reconstruction may also be more aesthetically pleasing and less psychologically distressing than an amputation.30 Patient factors are pivotal to successful tendon reconstruction, and functional outcomes depend on the patient age, general health status and medications, psychology, expectations, and adherence to postoperative rehabilitation.2 31 32 The treatment plan should be based on the expected levels of function that can feasibly be obtained after surgery and rehabilitation.

At the initial assessment, it is essential to know the mechanism and time of injury, location, degree and type of tissue loss, degree of nerve or tendon injury, quality of vascular supply, presenting contamination or infection, and the quality of the neighboring tissue. These factors are crucial when planning the optimal choice of reconstruction. The quality of vascular supply dictates the need for immediate revascularization by performing direct anastomosis, interposition of a vascular graft, or a flow-through free flap. Preoperative testing of sensibility and motor nerve supply is essential for the decision on the need for immediate nerve repair by suture or grafting.

Comprehensive debridement followed by prompt primary reconstruction is the gold standard in these cases. Ideally, multicomponent reconstruction should be achieved by the most reliable technique, including tendon reconstruction, with minimal donor site morbidity and with maximum functionality and aesthetic goals in mind. In most instances, the composite nature of these injuries predicates against a satisfactory outcome, and restoration of immediate tendon function is desirable, but often not achievable. Unlike in the lower extremity where delayed reconstruction is much better tolerated, early mobilization of the hand is essential to restore functionality.33 The crucial initial examination should include clinical observation of the finger cascade, tenodesis effect, passive movement in the fingers on squeeze compression of the forearm muscle bulk, individual active movement of distal interphalangeal (DIP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints by isolated flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) and flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) testing, as well as meticulous documentation of absent or damaged musculotendinous structures at the initial exploration and debridement.34 To enable satisfactory healing and gliding, a tendon requires a well-vascularized bed, stable bony fixation, a functioning flexor sheath (especially the A2 and A4 pulleys), and adequate and stable soft tissue coverage. These injuries are best treated by stable internal fixation of fractures to allow early active tendon mobilization. Exposed tendons require immediate coverage to prevent desiccation. More robust flap coverage is required in large soft tissue wounds such as degloving injuries as skin grafts will not adhere directly onto tendons in absence of paratenon. In instances when immediate tendon reconstruction is not achievable, delayed reconstruction is planned.

Primary Reconstruction

Primary reconstruction of either flexor or extensor tendons is desirable whenever possible. In the case of flexor tendons, ideal timing for the repair is within 2 weeks of injury.35 Primary repair obviates results in better functional outcomes than both delayed reconstruction and tendon grafting. Historically, primary repair was not performed in the case of lacerations of zone II, known as “no man's land,” due to the difficulty of repair and high complication rate in this region; however, in the last several decades, the development of superior suture materials and operative techniques have led to a change in this paradigm for zone II tendon lacerations.36 37

The authors endorse a wide-exposure Bruner incision to first explore the injury and to repair bone, joint, and neurovascular structures. The tendon repair begins with an epitendinous peripheral suture to gather in the tendon strands, followed by a four core-strand technique for adequate strength to initiate early active motion protocols. Passive flexion and extension should be tested intra-operatively to ensure that the tendons glide smoothly beneath the A2 and A4 pulleys and protect against PIP and DIP flexion deformities.36 Postoperatively, an early active motion protocol is recommended to prevent adhesion formation and facilitate healing without accidentally rupturing the tendon.

Although the FDP alone may be repaired in the setting of both FDS and FDP injury, the authors recommend repair of both tendons if feasible.36 38 Doing so prevents scarring of the free ends of an unrepaired FDS and subsequent development of adhesions. Dual reconstruction additionally provides security against failed repair in case either the FDS or FDP tendons rupture. A patient who has an intact FDS with an injured FDP may be able to adapt and avoid surgery and associated complications. If this patient is bothered by the lack of DIP flexion, arthrodesis at the DIP joint or FDP tenodesis may be helpful.39 40

Tendon grafting may be indicated in the settings of delays in recognition of a flexor tendon injury or wounds with extensive tendon loss that cannot be resolved by primary repair. Examples of candidates for tendon grafting include crush injuries, insufficient soft tissue coverage, those with comorbid conditions such as infection that prevent immediate surgery, segmental tendon loss, or failure of primary repair within 3 weeks of surgery (often due to lack of adherence to rehabilitation regimens).41 42 Beyond 3 weeks, primary repair is usually not possible due to swelling and extensive contraction. Primary reconstruction may be attempted after delayed presentation in the case of Leddy type II and III avulsions, in which the severed tendon does not retract into the palm.43

Delayed Reconstruction

If primary repair is not possible either due to delay or complexity of the injury, tendon grafting may be appropriate. The Boyes Preoperative Classification scheme can be used as a tool to assess the need for either a one- or two-stage repair. The indications for a one-stage repair include a properly healed wound, full passive range of motion, absence of significant scarring, an intact pulley system and tendon sheath, preserved neurovascular function, and absence of PIP joint flexion contracture upon initial wound exploration (Boyes grade 1; Table 1).43 If these conditions are not satisfied (Boyes grade 2–5; Table 1), patients are generally better candidates for two-stage reconstruction.

Table 1. Boyes Preoperative Classification Scheme.

| Grade | Preoperative condition |

|---|---|

| I | Good; minimal scar with mobile joints |

| II | Significant scarring |

| III | Joint damage with decreased range of motion |

| IV | Nerve damage |

| V | Multiple system injury; combination of above |

When assessing the possibility of a two-stage reconstruction, a key consideration is the patient's willingness to comply with hand rehabilitation protocols. Patients should undergo preoperative hand therapy to soften the scar; compliance with the preoperative rehabilitation increases the likelihood of completing the long and complicated postoperative hand therapy protocol necessary to make the reconstruction a success. In a patient unable or unwilling to endure this process, arthrodesis or amputation may be better alternatives.

One-Stage Reconstruction

In single-stage reconstruction, the FDP tendon is excised just proximal to the origin of the corresponding lumbrical muscle. This end serves as the proximal attachment site for the graft. The FDS tendon is left intact if it is not injured; otherwise, it is transected. Proximally, the FDS tendon may be used as the attachment site if the FDP is of an inferior quality.

The tendon graft is sutured to the FDP stump in the palm or distal forearm. The distal end of the graft is sutured to the subchondral bone at the base of the distal phalanx.42 The sequence in which proximal and distal attachments are performed is not standard. Most surgeons prefer adhering the distal end first, as the finger can be flexed more comfortably to determine graft length. However, others may choose to attach the graft at the proximal end first and adjust the length distally.44 45 46 47 48 Leading with the distal attachment allows for more precise tensioning of the graft, which is crucial for ensuring a good functional outcome.

To tension the graft, the tendon is attached at the proximal end with a single suture and compared with the other digits in the semiflexion position before reinforcement with additional sutures. A properly tensioned graft will result in a normal digital cascade, in which the small finger is in the position of greatest flexion and the index finger is held in the least flexion. A graft that is too tight will lead to a stiff finger with limited flexion, and a graft that is too loose can result in a “lumbrical plus” finger, in which the digit paradoxically extends at the PIP and DIP joints when the patient attempts flexion.36 41 49

Two-Stage Reconstruction

Stage 1

The general principle of a two-stage reconstruction is that the majority of repair occurs in the first stage, and ideally only the passing and suturing of the tendon graft is performed in the second stage.42 In the first stage, all joint deformities are corrected. The FDP tendon is transected distally to create a 1-cm stump just as in a one-stage repair, and the involved FDS is transected at the musculotendinous junction. Any remaining pulley and flexor retinacula are preserved as much as possible. The scared pulleys are reconstructed as necessary (A2 and A4). Classically, a silicone implant, known as the Hunter rod, is used as a spacer to prevent adhesions and to recreate a pseudosheath in preparation for a tendon graft in the second stage.

Pulley Reconstruction

The A2 and A4 annular pulleys are the most important components of the pulley system and must be intact for a functional pulley system. Lack of A2 and A4 leads to volar translation and “bowstringing” of the tendon; patients will report difficulty with grip strength. Damaged A2 or A4 pulleys are an indication for two-stage reconstruction, and they are reconstructed during the first stage (Fig. 1). Some surgeons believe that it is not required to repair A1, A3, and A5, although repairing them may provide better joint motion by keeping the tendon closer to the joint.49 50

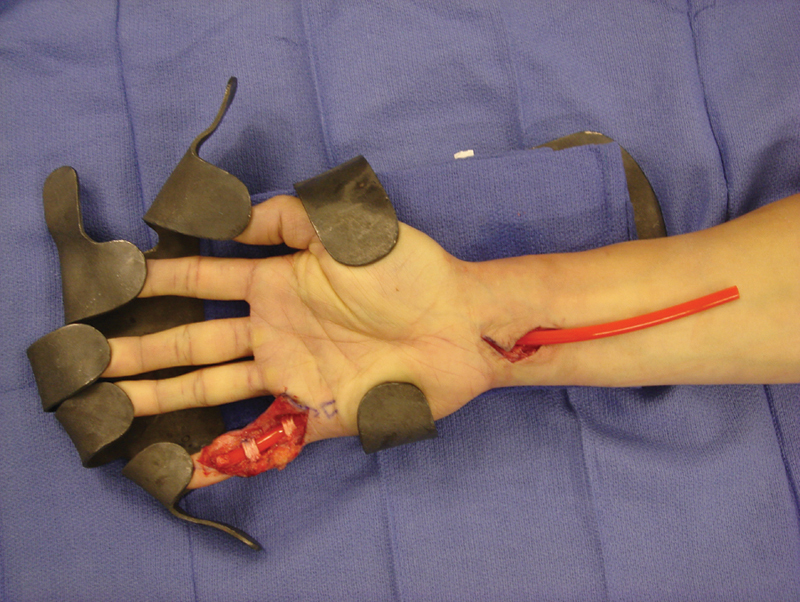

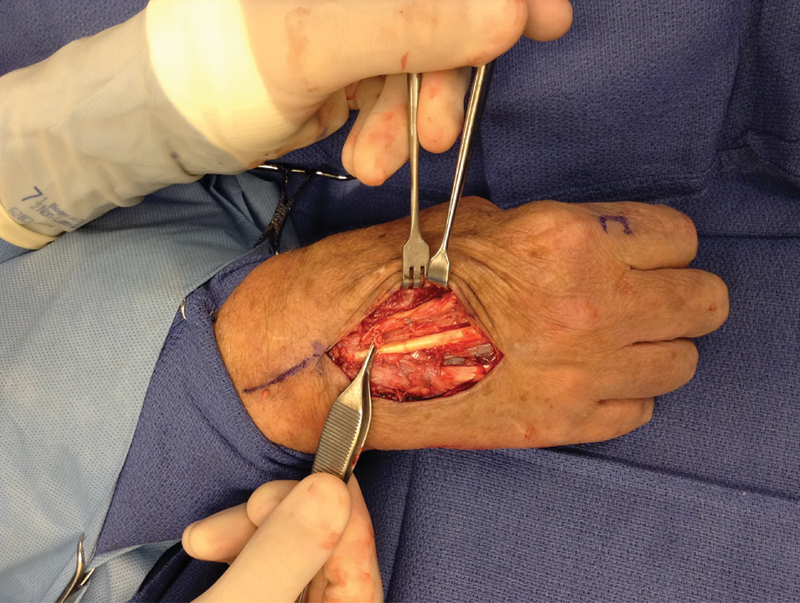

Fig. 1.

First-stage small finger flexor tendon reconstruction with A2 and A4 pulley repair.

The pulleys can be reconstructed by either weaving a flexor tendon or extensor retinaculum graft through the existing fibrous rim remnant or by creating new pulley loops around the bone. Each method has its drawbacks; the first method can result in a weaker pulley system, while the latter method may predispose the patient to ischemia or late fracture.49 Any scarred tissue should be excised before pulley reconstruction to prevent a weak and compromised repair. It is also essential to ensure that the pulleys do not entrap surrounding neurovascular bundles or extensor tendons, and that the eventual tendon graft will be able to glide smoothly.

Placement of Implant

A flexible silicone implant, referred to as the “Hunter rod” after the surgeon who helped develop the procedure, is placed to prevent adhesion formation between the stages of reconstruction. Hunter and Salisbury proposed using the implant during two-stage reconstruction based on the work of Bassett and Carroll, who found that a pseudosheath forms around the rod in the scarred finger.51 52 In the classic technique, the implant is sutured only to the distal phalanx and left free proximally in the distal forearm during the first stage. This allows free gliding of the implant and avoids further exacerbation of scarring in the palm. There should be a delay of at least 2 to 3 months between the first and second stages to allow time for an organized pseudosheath to form.41

Stage 2

In the Hunter technique, though the proximal end of the tendon graft is secured to the palm or distal forearm, the distal end is sutured to the implant. The implant is subsequently pulled through the tendon sheath and removed, and the distal end of the graft is sutured to the distal phalanx (Fig. 2).

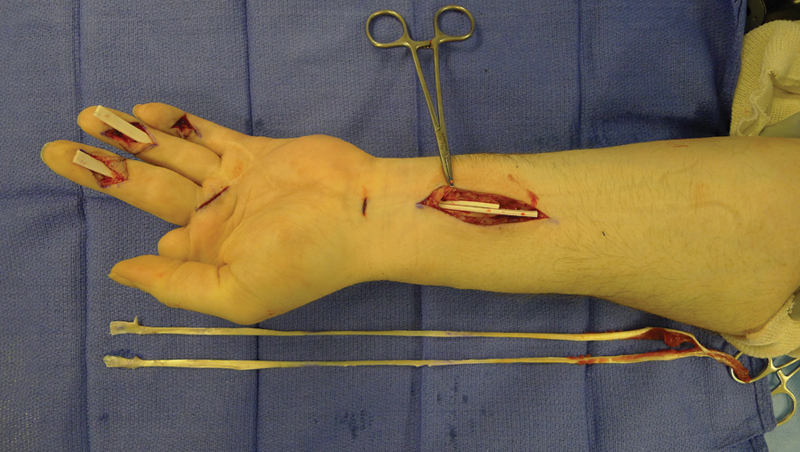

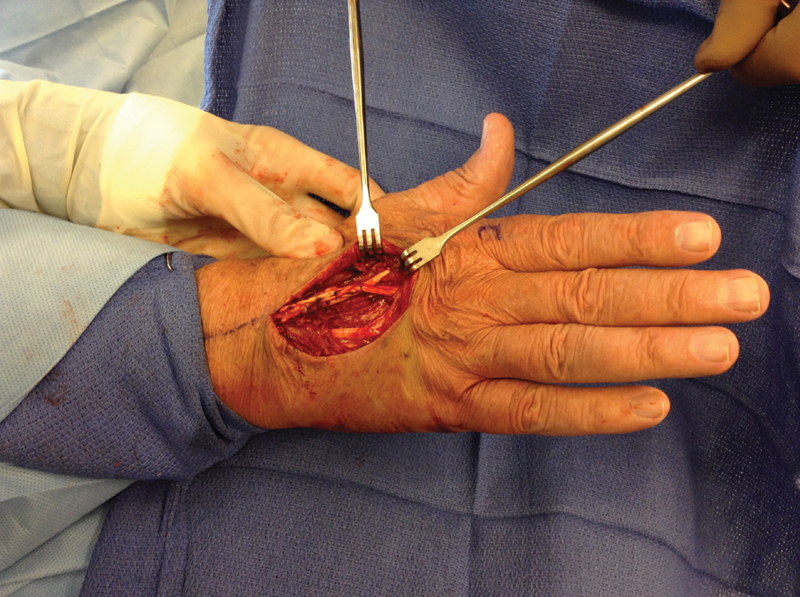

Fig. 2.

Stage 2 tendon reconstruction with toe extensor tendons to be passed through pseudosheaths formed by the Hunter rods.

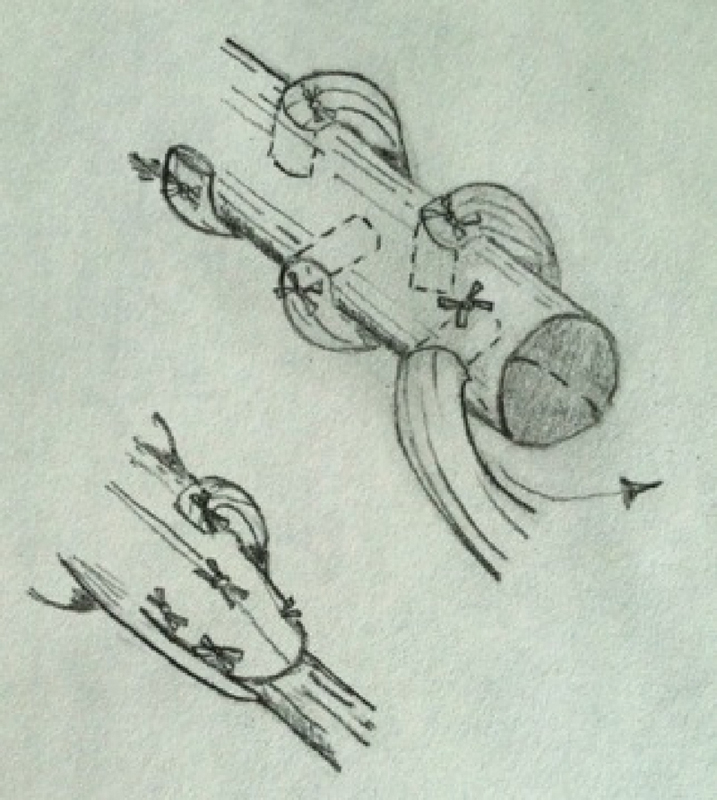

Proximally, the graft is secured with a Pulvertaft weave to the proximal tendon end (Fig. 3). The Pulvertaft weave involves passing the graft through the motor tendon at least 3 to 5 times and suturing in place. The technique enables easier adjustment of graft tension, provides superior strength over the end-to-end suture technique, and reduces the likelihood of gap formation and subsequent graft rupture.53 54 55 56 The end-to-end method, which involves suturing the ends of the motor and graft tendons together, is difficult to accomplish as the tendons are often of different sizes.

Fig. 3.

Pulvertaft weave.

Salvage Procedures

Tenolysis

Adhesion formation after surgical repair of flexor tendon injuries results in impaired tendon gliding and decreased range of motion. Adhesions generally occur at the graft tenorrhaphy sites or along the surface of the graft.41 Over time, the incidence of adhesions has decreased because of an understanding that early postoperative hand motion can dramatically improve outcomes. However, if hand rehabilitation regimens do not show improvement in active motion, tenolysis can be used to release adhesions.42 Many surgeons advocate waiting at least 3 to 6 months before tenolysis. Such a conservative approach stems from the technical difficulty that accompanies tenolysis as well as complications such as pain, excessive edema, neurovascular injury, and tendon rupture.36

Tenolysis is often performed under local anesthesia to evaluate intraoperative active motion and determine the need for joint release or grafting if scarring and contracture are too extensive for tenolysis alone.57 Just as in tendon repair, a Bruner incision is preferred for exposing the area of interest. Neurovascular structures, repaired tendons, and for the greater part, flexor sheath and pulleys should be identified and preserved. Adhesions should be dissected until full range of motion is achieved; in some cases, the FDS may have to be sacrificed to allow the FDP to glide.

Arthrodesis

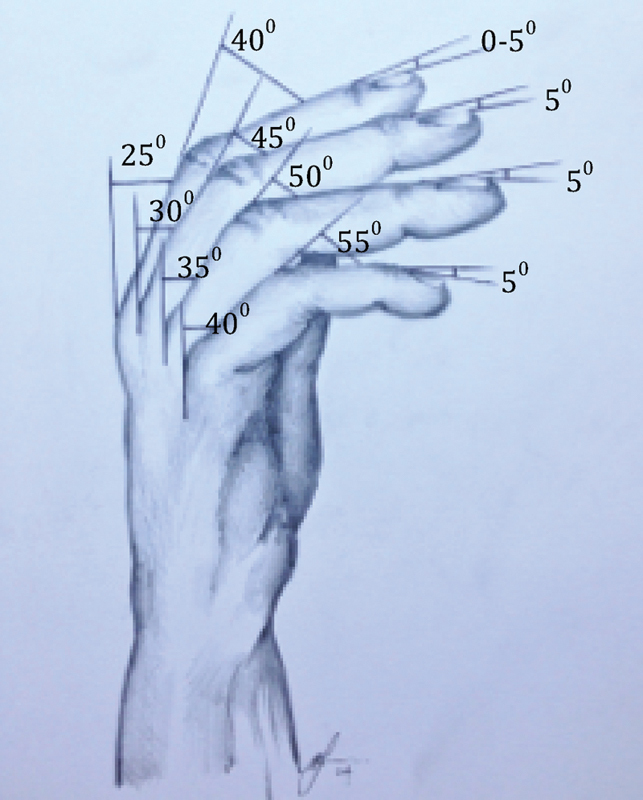

Arthrodesis may be indicated if a patient faces pain, instability, deformity, or inability to move at a particular joint (usually the PIP joint), but is unwilling or unable to undergo a complex reconstruction and recovery protocol, as is often seen in the elderly. The joint may be splinted or fixed temporarily to allow the patient to experience what hand function would be like after arthrodesis. Arthrodesis is performed to fix the digit in its position in the normal digital cascade (Fig. 4). Articular cartilage is removed around the joint, and the contact surfaces of the proximal and middle phalanges are shaped into a “cup” and “cone” that align in flexion of the joint.58 59 60 The joint is then fixed using Kirschner wire, screws, plates, or staples as per the surgeon's preference.

Fig. 4.

Normal digital cascade and position of arthrodesis.

Tendon Transfers

Tendon transfers are used to reconstitute the loss of function of a single tendon or group of tendons. The general principles of tendon transfers are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2. Principles of tendon transfers.

| Principle | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Amplitude of motion | The donor tendon should display similar excursion to the original tendon. |

| Power and control | Motor power of the donor tendon should match the recipient site function. Generally, at least one grade of motor power is lost during transfer. |

| One tendon–one function | Tendons lose effectiveness if they are transferred to perform more than one function. |

| Synergistic action | Muscles that normally act together to produce a composite movement should be used to replace each other whenever possible. |

| Line of pull | It is best if tendons travel directly from origin to insertion. Deviation of tendons around pulleys decreases effectiveness. |

| Expendability | Only expendable tendons should be transferred. |

Extensor System

The extensor tendon anatomy is such that lacerations or defects proximal to the juncturae may still allow extension of the involved digit(s) by pull from adjacent mechanisms. The four extensor digitorum communis tendons originate from a common muscle belly and have limited independent action whereas the extensor indicis proprius and extensor digiti minimi have independent muscle bellies and can be used for tendon transfer. It is crucial to remember that many established extensor imbalances will respond well to nonoperative treatment. Additionally, joint contractures are a contraindication to extensor reconstruction.

Proximally, as multiple tendons may be injured and identification can become more difficult, restoration of independent wrist and thumb extension should be given priority. The inability to extend the finger metacarpophalangeal joint (MCPJ) or radially abduct the thumb despite intact radial nerve function indicates a problem proximal to the MCPJ. Over time, unless the tendon is held by juncturae or there is substance loss, the motor unit will undergo myostatic contraction, precluding secondary repair. In the context of the extensor pollicis longus tendon, the extensor indicis proprius or palmaris longus is frequently used as a functional tendon transfer. For extensor communis reconstruction, the extensor indicis proprius, flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor carpi radialis, or side-to-side extensor communis transfers are used. In the forearm, pronator teres may be used to restore wrist extension.

More distally, finger extension is synergistic with wrist flexion, and controlled wrist function is essential to normal extensor mechanics. Thus, where there is extensive extensor loss, intact wrist flexors can be used as tendon transfer donors for finger extension. When planning such a reconstruction, evaluation of established extensor deficits must include the balance of all three finger joints as they are interrelated and treatment should be directed at the most proximal joint (Figs. 5, 6).61

Fig. 5.

This patient had an inability to extend his index finger and was found to have both index extensor tendons ruptured.

Fig. 6.

The index extensor digitorum communis (EDC) tendon has been repaired to the side of the middle finger EDC tendon using a Pulvertaft weave. Local anesthetic allows proper tensioning of the transfer.

Flexor System

Standard tendon transfers are shown in Table 3. Another approach to staged flexor tendon reconstruction is the Paneva–Holevich tenoplasty, which uses an FDS-FDP tendon transfer.62 The first stage involves dividing both flexors just distal to the lumbrical origin and repairing them end-to-end in the palm. Once healed, the second stage requires exposure of the tendon sheath distally and removal of the distal FDS and FDP tendons. In zone V, the FDS tendon is released at the musculotendinous junction and the more proximal stump of the FDS is sutured to the side of the FDP tendon. This graft is pulled distally through the synovial sheath so that it can be sutured to the distal phalanx of the digit. Modifications have been described removing distal FDS and FDP at the first stage and utilizing a silicone rod that allows for pseudosheath formation. Some authors have advocated this technique over traditional two-stage techniques as it transports intrasynovial tendon graft material with a lower risk of adhesions.62 63 However, tensioning of the graft can be difficult.

Table 3. Common tendon transfers.

| Deficient tendon | Donor tendon | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Biceps | Pectoralis major Latissimus dorsi |

Elbow flexion |

| Steindler flexorplasty | Common flexor mass | |

| Triceps | Deltoid, latissimus dorsi, or biceps | Elbow extension |

| ECRB | PT | Wrist extension |

| EDC | FDS, FCR, or FCU | Finger extension |

| EPL | PL, FDS, EIP | Thumb extension |

| APB | FDS (ring) | Thumb opposition and abduction |

| APB | EIP | |

| FPL | BR | Thumb IP flexion |

| FDP of index and middle | FDP of ring and small finger | Index and long finger flexion |

| Adductor pollicis | FDS or ECRB | Thumb adduction |

| First dorsal interosseus | APL, ECRL, or EIP | Finger abduction (index) |

| Lateral bands of ulnar digits | FDS, ECRL | Reverse clawing effect |

Abbreviations: APB, abductor pollicis brevis; APL, abductor pollicis longus; BR, brachioradialis; ECRB, extensor carpi radialis brevis; ECRL, extensor carpi radialis longus; EDC, extensor digitorum communis; EIP, extensor indicis proprius; EPL, extensor pollicis longus; FCR, flexor carpi radialis; FCU, flexor carpi ulnaris; FDP, flexor digitorum profundus; FDS, flexor digitorum superficialis; FPL, flexor pollicis longus; IP, interphalangeal; PL, palmaris longus; PT, posterior tibial.

The transfer of islanded flexor tendon vascularized by mesotendon is also well described.64 The technique includes using the transfer of FDS of the ring finger to repair a tendon defect—commonly for FDP reconstruction with the FDS in place. This technique has the advantage of providing like-for-like reconstruction with all its gliding surfaces intact and is potentially advantageous when encountering extensive adhesions and has the added merit of being a one-stage procedure.

Composite Transfers

Vital structures such as bone, muscle, blood vessels, nerves, and tendons are often exposed or may be missing in complex trauma of the upper limb. This has profound consequences given the unique functional and anatomical complexity of the region. The utility of surgical flaps and primary repair of all structures in injuries involving compound fractures and extensive soft tissue damage is well established. Reconstruction must include consideration of not only stable well-vascularized tissue, but also functionality.65 The advantages of composite reconstruction are now well accepted and include primary bone and soft tissue healing, decreased risk of infection, and a reduction in the length of hospital stay and costs as well as improving long-term functional outcomes. Many flaps have been described in upper extremity reconstruction. Table 4 outlines some commonly used flaps for musculotendinous composite reconstruction in the upper limb.

Table 4. Common flaps for upper limb composite reconstruction.

| Flap | Possible components |

|---|---|

| Radial forearm | Skin, fascia, bone, lateral, antebrachial cutaneous nerve and vascularized palmaris longus tendon. |

| Dorsalis pedis | Skin, fascia, superficial peroneal nerve, vascularized extensor digitorum longus/extensor hallucis brevis |

| Gracilis muscle | Skin, muscle, tendon, nerve |

| Latissimus dorsi muscle | Skin, muscle, tendon, nerve |

Postoperative Rehabilitation

Proper postoperative care is crucial to the treatment of hand injuries. A holistic rehabilitation may include static and dynamic bracing, physical therapy, occupational therapy, psychological support, and social assistance.66 Historically, hands were immobilized after flexor tendon repair to avoid rupture. However, studies have shown that controlled early postoperative motion facilitates intrinsic healing, strengthens the repair, and reduces the formation of adhesions, leading to the development of passive motion protocols and later, active motion protocols.67 68 69 Postoperative immobilization is still sometimes indicated in elderly or very young patients who may not be compliant with hand therapy, as well as in patients with conditions that could affect tendon healing, such as rheumatoid arthritis.70

Although hand rehabilitation regimens should be tailored to the patient by qualified therapists, the most widely adopted protocol combines passive and active motion. In approaching flexor tendons, the patient's wrist is blocked at neutral using a dorsal blocking splint, the MCP joints at 80-degree flexion, and the PIP and DIP joints in full extension. For the first 3 weeks postoperatively, the patient is instructed to perform hourly “place and hold exercises” with passive flexion of the individual PIP and DIP joints as well as active flexion and extension within the splint, with the goal of increasing tendon excursion. Compression wraps are used to reduce edema. After 6 weeks, the patient may remove the splint for progressive active flexion of isolated digits as well as progressive ADL (activities of daily living) training. At 3 months, strengthening exercises using resistance may be introduced. At 6 months, if significant progress in increasing hand range-of-motion has not been achieved, additional salvage procedures such as tenolysis may be considered.

New Directions

The lack of intrasynovial tendon graft sources together with a high risk of adhesion formation and disabling donor site morbidity challenge the current tendon reconstruction techniques in complex upper limb trauma. Tissue engineering to provide “off the shelf” tendon grafts would offer a needed solution to these clinical challenges. The solution should involve the combination of candidate cells and supporting scaffolds together with stimulation strategies to enhance tendon graft healing. New directions in scaffold development, stem cell technology, and growth factor supplementation and modulation all aid in striking the balance between optimal tendon engraftment, biomechanical strength, and maintenance of a gliding surface to provide a potential opportunity to revolutionize the management of these injuries.

The first step in creating a tissue-engineered tendon is the development of a suitable three-dimensional scaffold. Both synthetic and biological scaffolds have been used with a recent trend toward chemically and ultrasonically decellularized cadaveric flexor tendons.71 72 73 74 75 76 77 It has been demonstrated that constructs treated in this way have reduced immunogenicity, but retained biomechanical strength and allow increased cellular penetration and migration when reseeded.78 79 Many cells of differentiated and undifferentiated phenotypes have been used for this purpose, but stem cells provide the most clinical relevance. In particular, adipose-derived stem cells offer the best advantage due to their abundance, ease of harvest, expendability, and proliferative capacity.80

Growth factor supplementation of reseeded cells with basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and platelet-derived growth factor- (PDGF-BB) has been shown to be effective at high doses and in combination to promote proliferation within the scaffold construct.81 Suppression of other growth factors may equally improve the outcome. For example, when tumor growth factor-β (TGF-β) expression, which has been implicated in adhesion formation, is reduced, there is a reduction in this phenomenon.82 83 To allow for early active mobilization, a tissue-engineered tendon requires a secure bony attachment. This is not always possible, especially in complex injuries at the tendon–bone interface. Conventional repairs of this highly specialized area produce suboptimal healing with increased risk of failure.84 85 86 87 88 Therefore, attempts have been made to engineer new tendon–bone interfaces through decellularization to promote more robust bone–bone and bone–tendon healing and deliver greater biomechanical stability as shown in a cadaveric human model.89 90 It is our hope that off-the-shelf tendon–bone constructs will become clinically available in the very near future for surgeons to use in reconstructing complex mutilating injuries of the upper limb.

References

- 1.Nance M L, Ed. National Trauma Data Bank Annual Report 2013 Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bueno R A Jr, Neumeister M W. Outcomes after mutilating hand injuries: review of the literature and recommendations for assessment. Hand Clin. 2003;19(1):193–204. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0712(02)00142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevanovic M, Gutow A P, Sharpe F. The management of bone defects of the forearm after trauma. Hand Clin. 1999;15(2):299–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beyer C W, Dick W F. Johann Friedrich August von Esmarch—a pioneer in the field of emergency and disaster medicine. Resuscitation. 2001;50(2):131–133. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(01)00371-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang A Y, Chang J. Tissue engineering of flexor tendons. Clin Plast Surg. 2003;30(4):565–572. doi: 10.1016/s0094-1298(03)00074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potenza A D. Critical evaluation of flexor-tendon healing and adhesion formation within artificial digital sheath. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1963;45:1217–1233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taras J S, Gray R M, Culp R W. Complications of flexor tendon injuries. Hand Clin. 1994;10(1):93–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lister G. Pitfalls and complications of flexor tendon surgery. Hand Clin. 1985;1(1):133–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seiler J G III, Chu C R, Amiel D, Woo S L, Gelberman R H. The Marshall R. Urist Young Investigator Award. Autogenous flexor tendon grafts. Biologic mechanisms for incorporation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;(345):239–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peacock E E Jr. Biological principles in the healing of long tendons. Surg Clin North Am. 1965;45:461–476. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)37543-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lieberman J R, Lozman J, Czajka J, Dougherty J. Repair of Achilles tendon ruptures with Dacron vascular graft. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;(234):204–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holtz M, Midenberg M L, Kirschenbaum S E. Utilization of a silastic sheet in tendon repair of the foot. J Foot Surg. 1982;21(4):253–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie R G, Tang J B. Allograft tendon for second-stage tendon reconstruction. Hand Clin. 2012;28(4):503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johansen K Daines M Howey T Helfet D Hansen S T Jr Objective criteria accurately predict amputation following lower extremity trauma J Trauma 1990305568–572., discussion 572–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sloan J P, Dove A F, Maheson M, Cope A N, Welsh K R. Antibiotics in open fractures of the distal phalanx? J Hand Surg [Br] 1987;12(1):123–124. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681_87_90076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzgerald R H Jr, Cooney W P III, Washington J A II, Van Scoy R E, Linscheid R L, Dobyns J H. Bacterial colonization of mutilating hand injuries and its treatment. J Hand Surg Am. 1977;2(2):85–89. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(77)80088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Covey D C. Blast and fragment injuries of the musculoskeletal system. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A(7):1221–1234. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200207000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okike K, Bhattacharyya T. Trends in the management of open fractures. A critical analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(12):2739–2748. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tintle S M, Baechler M F, Nanos G P III, Forsberg J A, Potter B K. Traumatic and trauma-related amputations: Part II: Upper extremity and future directions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(18):2934–2945. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dirschl D R, Dahners L E. The mangled extremity: when should it be amputated? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1996;4(4):182–190. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199607000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howe H R Jr, Poole G V Jr, Hansen K J. et al. Salvage of lower extremities following combined orthopedic and vascular trauma. A predictive salvage index. Am Surg. 1987;53(4):205–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russell W L Sailors D M Whittle T B Fisher D F Jr Burns R P Limb salvage versus traumatic amputation. A decision based on a seven-part predictive index Ann Surg 19912135473–480., discussion 480–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNamara M G, Heckman J D, Corley F G. Severe open fractures of the lower extremity: a retrospective evaluation of the Mangled Extremity Severity Score (MESS) J Orthop Trauma. 1994;8(2):81–87. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199404000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lange R H, Bach A W, Hansen S T Jr, Johansen K H. Open tibial fractures with associated vascular injuries: prognosis for limb salvage. J Trauma. 1985;25(3):203–208. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198503000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slauterbeck J R, Britton C, Moneim M S, Clevenger F W. Mangled extremity severity score: an accurate guide to treatment of the severely injured upper extremity. J Orthop Trauma. 1994;8(4):282–285. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199408000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei F C Loftus J B Metacarpal hand: a classification as a guide to reconstruction Abstract presented at: The Annual Meeting of the American Association for Hand Surgery; December 1–4, 1993; Cancun, Mexico

- 27.Reid D AC, Tubiana R. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 1984. Mutilating Injuries of the Hand. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinzweig J, Weinzweig N. The “Tic-Tac-Toe” classification system for mutilating injuries of the hand. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100(5):1200–1211. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199710000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Durham R M Mistry B M Mazuski J E Shapiro M Jacobs D Outcome and utility of scoring systems in the management of the mangled extremity Am J Surg 19961725569–573., discussion 573–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tintle S M, Keeling J J, Shawen S B, Forsberg J A, Potter B K. Traumatic and trauma-related amputations: part I: general principles and lower-extremity amputations. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(17):2852–2868. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neumeister M W Brown R E Mutilating hand injuries: principles and management Hand Clin 20031911–15., v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta A, Shatford R A, Wolff T W, Tsai T M, Scheker L R, Levin L S. Treatment of the severely injured upper extremity. Instr Course Lect. 2000;49:377–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yaremchuk M J, Brumback R J, Manson P N, Burgess A R, Poka A, Weiland A J. Acute and definitive management of traumatic osteocutaneous defects of the lower extremity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80(1):1–14. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198707000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayton M. Assessment of hand injuries. Curr Orthop. 2002;16:246–254. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lehfeldt M Ray E Sherman R MOC-PS(SM) CME article: treatment of flexor tendon laceration Plast Reconstr Surg 2008121(4, Suppl):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Momeni A, Grauel E, Chang J. Complications after flexor tendon injuries. Hand Clin. 2010;26(2):179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griffin M, Hindocha S, Jordan D, Saleh M, Khan W. An overview of the management of flexor tendon injuries. Open Orthop J. 2012;6 01:28–35. doi: 10.2174/1874325001206010028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang J B. Tendon injuries across the world: treatment. Injury. 2006;37(11):1036–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bora F W Jr. Profundus tendon grafting with unimpaired sublimus function in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1970;71(71):118–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coyle M P Jr, Leddy T P, Leddy J P. Staged flexor tendon reconstruction fingertip to palm. J Hand Surg Am. 2002;27(4):581–585. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2002.34319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Freilich A M, Chhabra A B. Secondary flexor tendon reconstruction, a review. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32(9):1436–1442. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldfarb C A, Gelberman R H, Boyer M I. Flexor tendon reconstruction: current concepts and techniques. J Am Soc Surg Hand. 2005;5(2):123–130. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leddy J P, Packer J W. Avulsion of the profundus tendon insertion in athletes. J Hand Surg Am. 1977;2(1):66–69. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(77)80012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Forward A D Cowan R J; AD; Clinical Congress XI. Experimental suture of tendon to bone Surg Forum 196011458–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kerwein G A. A study of tendon implantations into bone. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1942;75:794–796. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kinmonth J B. The cut flexor tendon: experiences with free grafts and steel wire fixation. Br J Surg. 1947;35(137):29–36. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18003513705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weiner D, Hoffman S, Barsky A J. Improved method for distal attachment of flexor tendon grafts. Modification of Stenström technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968;41(1):71–74. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196801000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson R L. Flexor tendon grafting. Hand Clin. 1985;1(1):97–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clark T A, Skeete K, Amadio P C. Flexor tendon pulley reconstruction. J Hand Surg [Br] 2010;35A:1685–1689. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barton N J. Experimental study of optimal location of flexor tendon pulleys. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1969;43(2):125–129. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196902000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hunter J M, Salisbury R E. Flexor-tendon reconstruction in severely damaged hands. A two-stage procedure using a silicone-dacron reinforced gliding prosthesis prior to tendon grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53(5):829–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bassett C AL, Carroll R E. Formation of tendon sheaths by silicone rod implants. Proceedings of American Society for Surgery of the Hand. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1963;(45):884. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leddy J, Dennis T. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1992. Tendon injuries; pp. 175–207. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lundborg G, Rank F. Experimental studies on cellular mechanisms involved in healing of animal and human flexor tendon in synovial environment. Hand. 1980;12(1):3–11. doi: 10.1016/s0072-968x(80)80023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pribaz J J, Morrison W A, Macleod A M. Primary repair of flexor tendons in no-man's land using the Becker repair. J Hand Surg [Br] 1989;14(4):400–405. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681_89_90155-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verdan C E. Half a century of flexor-tendon surgery. Current status and changing philosophies. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(3):472–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feldscher S B, Schneider L H. Flexor tenolysis. Hand Surg. 2002;7(1):61–74. doi: 10.1142/s0218810402000819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watson H K, Shaffer S R. Concave-convex arthrodeses in joints of the hand. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1970;46(4):368–371. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197010000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carroll R E, Hill N A. Small joint arthrodesis in hand reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51(6):1219–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tubiana R. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1985. Arthrodesis of the fingers; pp. 698–702. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Urbaniak J R, Hayes M G. Chronic boutonniere deformity—an anatomic reconstruction. J Hand Surg Am. 1981;6(4):379–383. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(81)80048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paneva-Holevich E. Two-stage tenoplasty in injury of the flexor tendons of the hand. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51(1):21–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beris A E, Darlis N A, Korompilias A V, Vekris M D, Mitsionis G I, Soucacos P N. Two-stage flexor tendon reconstruction in zone II using a silicone rod and a pedicled intrasynovial graft. J Hand Surg Am. 2003;28(4):652–660. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(03)00146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guimberteau J C, Bakhach J, Panconi B, Rouzaud S. A fresh look at vascularized flexor tendon transfers: concept, technical aspects and results. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60(7):793–810. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Payatakes A H, Zagoreos N P, Fedorcik G G, Ruch D S, Levin L S. Current practice of microsurgery by members of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32(4):541–547. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grunert B K, Smith C J, Devine C A. et al. Early psychological aspects of severe hand injury. J Hand Surg [Br] 1988;13(2):177–180. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681_88_90132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Duran R J, Houser R G. St. Louis, MO: CV Mosby; 1975. Controlled passive motion following flexor tendon repairs in zones 2 and 3. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kleinert H E, Kutz J E, Atasoy E, Stormo A. Primary repair of flexor tendons. Orthop Clin North Am. 1973;4(4):865–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Small J O, Brennen M D, Colville J. Early active mobilisation following flexor tendon repair in zone 2. J Hand Surg [Br] 1989;14(4):383–391. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681_89_90152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rust P A, Eckersley R. Twenty questions on tendon injuries in the hand. Curr Orthop. 2008;22:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yokoya S, Mochizuki Y, Natsu K, Omae H, Nagata Y, Ochi M. Rotator cuff regeneration using a bioabsorbable material with bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a rabbit model. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(6):1259–1268. doi: 10.1177/0363546512442343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Manning C N, Schwartz A G, Liu W. et al. Controlled delivery of mesenchymal stem cells and growth factors using a nanofiber scaffold for tendon repair. Acta Biomater. 2013;9(6):6905–6914. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vaquette C, Slimani S, Kahn C J, Tran N, Rahouadj R, Wang X. A poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) knitted scaffold for tendon tissue engineering: an in vitro and in vivo study. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2010;21(13):1737–1760. doi: 10.1163/092050609X12560455246676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Young R G, Butler D L, Weber W, Caplan A I, Gordon S L, Fink D J. Use of mesenchymal stem cells in a collagen matrix for Achilles tendon repair. J Orthop Res. 1998;16(4):406–413. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100160403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Caliari S R, Ramirez M A, Harley B A. The development of collagen-GAG scaffold-membrane composites for tendon tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2011;32(34):8990–8998. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Murphy K D, Mushkudiani I A, Kao D, Levesque A Y, Hawkins H K, Gould L J. Successful incorporation of tissue-engineered porcine small-intestinal submucosa as substitute flexor tendon graft is mediated by elevated TGF-beta1 expression in the rabbit. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33(7):1168–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abousleiman R I, Reyes Y, McFetridge P, Sikavitsas V. Tendon tissue engineering using cell-seeded umbilical veins cultured in a mechanical stimulator. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15(4):787–795. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Raghavan S S Woon C Y Kraus A et al. Human flexor tendon tissue engineering: decellularization of human flexor tendons reduces immunogenicity in vivo Tissue Eng Part A 2012. a;187-8796–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Woon C Y, Pridgen B C, Kraus A, Bari S, Pham H, Chang J. Optimization of human tendon tissue engineering: peracetic acid oxidation for enhanced reseeding of acellularized intrasynovial tendon. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(3):1107–1117. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318205f298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Uysal C A, Tobita M, Hyakusoku H, Mizuno H. Adipose-derived stem cells enhance primary tendon repair: biomechanical and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65(12):1712–1719. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Raghavan S S Woon C Y Kraus A Megerle K Pham H Chang J Optimization of human tendon tissue engineering: synergistic effects of growth factors for use in tendon scaffold repopulation Plast Reconstr Surg 2012. b;1292479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Katzel E B, Wolenski M, Loiselle A E. et al. Impact of Smad3 loss of function on scarring and adhesion formation during tendon healing. J Orthop Res. 2011;29(5):684–693. doi: 10.1002/jor.21235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Branford O A, Klass B R, Grobbelaar A O, Rolfe K J. The growth factors involved in flexor tendon repair and adhesion formation. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2014;39(1):60–70. doi: 10.1177/1753193413509231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Genin G M, Kent A, Birman V. et al. Functional grading of mineral and collagen in the attachment of tendon to bone. Biophys J. 2009;97(4):976–985. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Thomopoulos S, Williams G R, Gimbel J A, Favata M, Soslowsky L J. Variation of biomechanical, structural, and compositional properties along the tendon to bone insertion site. J Orthop Res. 2003;21(3):413–419. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(03)00057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Thomopoulos S, Marquez J P, Weinberger B, Birman V, Genin G M. Collagen fiber orientation at the tendon to bone insertion and its influence on stress concentrations. J Biomech. 2006;39(10):1842–1851. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thomopoulos S Genin G M Galatz L M The development and morphogenesis of the tendon-to-bone insertion - what development can teach us about healing - J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 2010. b;10135–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Silva M J, Thomopoulos S, Kusano N. et al. Early healing of flexor tendon insertion site injuries: Tunnel repair is mechanically and histologically inferior to surface repair in a canine model. J Orthop Res. 2006;24(5):990–1000. doi: 10.1002/jor.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bronstein J A, Woon C Y, Farnebo S. et al. Physicochemical decellularization of composite flexor tendon-bone interface grafts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(1):94–102. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318290f5fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fox P M, Farnebo S, Lindsey D, Chang J, Schmitt T, Chang J. Decellularized human tendon-bone grafts for composite flexor tendon reconstruction: a cadaveric model of initial mechanical properties. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(12):2323–2328. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.08.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]