Abstract

Backscattering interferometry enables the detection of syphilis antibody–antigen interactions in the presence of human serum, showing promise as a diagnostic tool for the serological diagnosis of infectious disease with potentially quantitative capabilities.

Backscattering interferometry (BSI) is a versatile sensing technique that is widely applicable in biochemical and biophysical investigations,1-5 including the study of free-solution, label-free molecular interactions at picomolar solute concentrations.6-8 BSI employs a simple optical train consisting of a helium–neon laser, a microfluidic chip, and a position sensing camera to measure these interactions rapidly (in seconds) using picolitre detection volumes. This ability makes BSI unique among sensing techniques; the consequence is a reduction in time and expense, especially because labeling and immobilization strategies are not needed. Here we show that BSI can be used to detect antibody–antigen complexes in free solution and in the presence of human serum, demonstrating the prospect of using the approach to detect and quantify specific antibody levels in clinical samples. These capabilities would not only constitute a highly sensitive and quantitative in vitro immunodiagnostic test for reactive serum antibodies, but, in some applications, could also provide valuable information concerning efficacy of treatment. For these studies, syphilis serology was used as a model for evaluating the diagnostic potential of BSI.

Current diagnostic tools rely heavily on signaling moieties to detect the presence of a particular antigen or antibody in a sample. Such chemical labeling both adds complexity to the assays and potentially increases costs.9,10 Diagnostic assays for diseases of global importance, such as syphilis, are particularly sensitive to these concerns. Therefore, a label-free microfluidic diagnostic tool has the potential to revolutionize point-of-care immunodiagnostics for syphilis and other common diseases. Successful serological detection of syphilis infection in human serum specimens using BSI may not only provide innovative diagnostic approaches for this particular infection, but could also serve as a benchmark for immunodiagnostics which could be applied to countless other diseases.

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infectious disease caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum for which no adequate in vitro culture method has been developed.11-14 Therefore, apart from direct detection of T. pallidum from skin lesions early in the progress of the disease using microscopy or molecular methods, the majority of syphilis cases are diagnosed as a result of serological testing.9,13,14 Classically, the serological diagnosis of syphilis relies on the detection of two distinct antibodies, namely heterophile antibodies directed against lipoidal material released from damaged host cells and possibly from the treponemes themselves (non-treponemal antibodies or reagin) and antibodies directed against T. pallidum-specific surface antigens (treponemal antibodies).13,14 Traditionally, the antigen used in non-treponemal assays, such as the Rapid Plasma Reagin (RPR) and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) tests, is a mixture of cardiolipin, lecithin, and cholesterol.14 These non-treponemal antibody tests are good indicators of active infection and are relatively inexpensive.15 Additionally, since levels of non-treponemal antibodies can be quantified (i.e., specimens may be classified according to titer strength), a significant reduction in titer can be used to indicate success of therapy while a significant increase can indicate possible relapse or re-infection.14,15 However, false-positive non-treponemal reactions can occur with sera obtained from persons with other conditions including acute viral infections, malaria, autoimmune diseases, tuberculosis, pregnancy, and vaccination.12-15 In contrast, treponemal assays such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test,13,14 the T. pallidum passive particle agglutination assay (TP-PA),13 and treponemal enzyme immunoassays (EIAs),11,14 detect antibodies directed against specific T. pallidum antigens or recombinants, such as the 15, 17, or 47 kD lipoproteins.16 While these tests are highly specific, they are considerably more expensive and generally remain positive for life, even following the administration of successful therapy.13-15 Classically, the treponemal tests have primarily been used to confirm the specificity of reactive non-treponemal screening tests.11-15 The application of BSI to syphilis diagnostics would enable both treponemal and non-treponemal tests to be performed rapidly in a low-volume assay format without the use of fluorescent tags, visualizing agents, or microscopy, which are required by existing syphilis tests.14 The use of BSI may therefore decrease time and cost considerations of routine testing, and may also enhance the quantitative potential of non-treponemal tests.

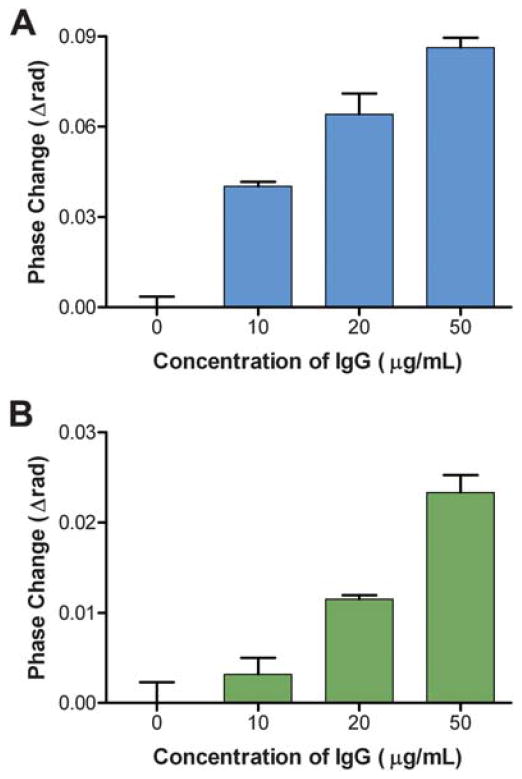

Initial experiments evaluated BSI’s ability to detect the reaction of a purified recombinant treponemal antigen r17 (Genway Biotech, Inc.) with affinity purified total human immunoglobin G (IgG) from a patient proven to be seropositive for syphilis in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). This assay was designed to establish whether BSI was capable of detecting the binding of this particular antigen–antibody system in a simple buffer matrix. Increasing concentrations of total IgG were prepared in PBS, and each concentration was mixed with the r17 antigen preparation. The final concentrations of the total IgG were 0–50 μg mL−1 and the final antigen concentration was 100 μg mL−1. The BSI signal was measured for each sample after equilibration, and the bulk contributions of IgG and antigen were subtracted. The remaining signal representing the binding signal that arises solely from the antigen–antibody interaction (calculated as a change in phase using a Fourier analysis, ESI†) was plotted versus the IgG concentration (Fig. 1A). These data confirmed that the binding of the total human IgG to a specific treponemal antigen produced a BSI signal. As expected, the magnitude of the phase change correlated with the quantity of IgG in the sample (and therefore the number of binding reactions that occurred) when the antigen was present in excess. It should be noted that this IgG preparation consisted of total IgG and was not limited to IgG molecules specific to the r17 syphilis antigen. Therefore, the IgG concentrations used here do not denote the actual quantity of IgG molecules available to bind the antigen; consequentially, no affinity information regarding the interaction can be inferred.

Fig. 1.

Binding of total IgG from an infected patient with treponemal r17 antigen in A) PBS buffer and B) human serum. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three trials.

After establishing that the reaction of r17 to total IgG was indeed measurable using BSI, parallel experiments explored BSI’s capacity to detect this same reaction in the presence of a human serummatrix. Increasing concentrations of total IgG were spiked into a diluted nonreactive commercial serum (Phoenix Bio-Tech Corporation, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada), and were then mixed with r17 antigen. The final mixtures contained a 1 : 40 dilution of serum and an r17 antigen concentration of 100 μg mL−1 with IgG concentrations ranging from 0 to 50 μg mL−1. BSI data were collected as previously described and the binding of the treponemal antigen with the IgG in the presence of human serum is shown in Fig. 1B. These results indicate that the reaction of r17 with total IgG from an infected patient can be detected in the presence of a complex human serum matrix. This is a significant discovery, showing that BSI can be implemented as a reactive serum assay system and for other immunodiagnostic applications. Furthermore, the BSI signal continues to correlate with the IgG concentration in the presence of excess antigen, illustrating the quantitative potential of BSI in evaluating clinical samples. However, as shown in Fig. 1, a markedly lower signal was observed for corresponding total IgG concentrations when reacted in the presence of serum rather than in a buffer matrix. This decrease in signal may be due to nonspecific binding between serum proteins and IgG, lowering the effective IgG concentration in the assay, a factor which may warrant consideration when designing clinical assays.

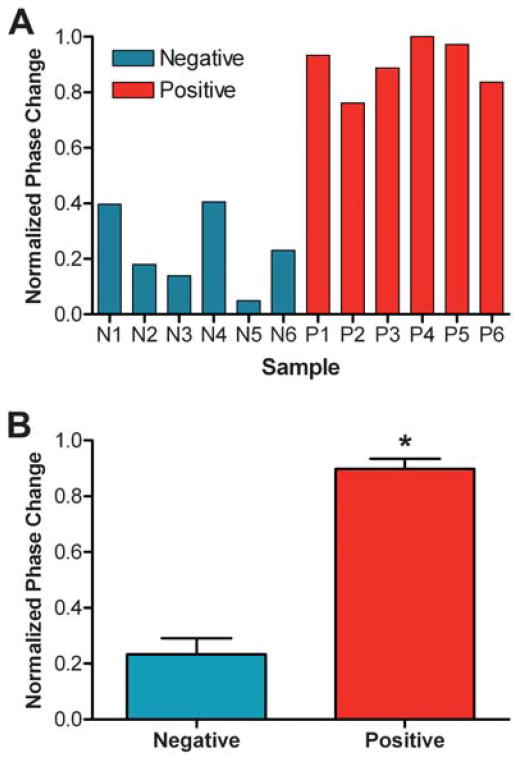

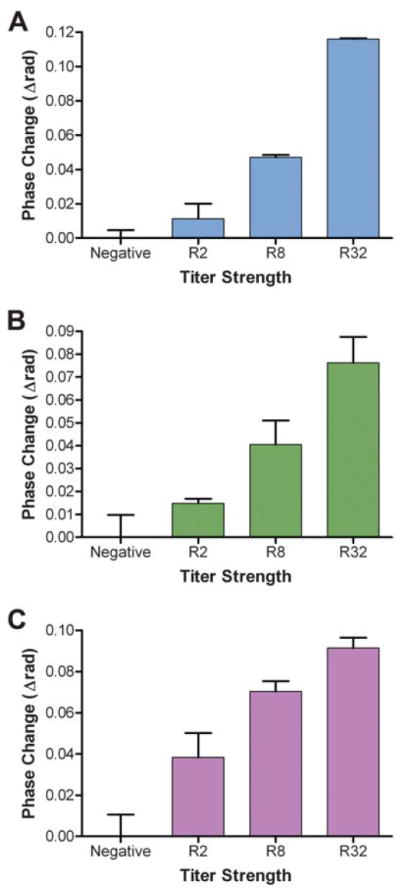

Our investigations were then expanded to explore the potential performance of BSI as a reactive serum assay system by measuring the interaction of r17 with human serumsamples obtained from both healthy individuals and those known to be seropositive for syphilis. These human samples were previously characterized according to their patterns of reactivity using both the quantitative non-treponemal RPR and the treponemal TP-PA test. For BSI assays, all serum samples were first diluted with PBS and then mixed with r17 antigen or one of three non-treponemal antigen preparations containing cardiolipin [one of three different proteins: synthetic multiple antigen peptide system (MAPS), bovine serum albumin, or chicken IGY antibody, covalently modified with cardiolipin] to yield solutions with a final serum dilution of 1 : 20 and a final antigen concentration of 5 μg mL−1. The binding signal of the interaction was measured and plotted against designated serum sample number, reactivity in the TP-PA test (Fig. 2) and by RPR titer (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

A) BSI signal resulting from the reaction of twelve clinical samples with the treponemal r17 antigen. B) Average signal for positive and negative samples, demonstrating a statistically significant separation (*p = 2 × 10−6). Error bars represent the standard deviation between each set of samples (n = 6).

Fig. 3.

BSI signal resulting from the binding of pre-characterized human serum samples and three different cardiolipin-based (non-treponemal) antigens. These antigens included three different proteins (A. Synthetic MAPS, B. Bovine serum albumin, and C. Chicken IGY antibody) covalently modified with cardiolipin. Error bars represent the standard deviation of results of triplicate assays.

A statistically significant separation (p = 2 × 10−6) between BSI signals recorded for positive and negative samples was achieved using the r17 antigen (Fig. 2B), suggesting that a signal threshold can be established for determining the treponemal reactivity of unclassified samples. The resultant BSI signals from the reactions of three different cardiolipin-based antigens with human sera of four different levels of reactivity, according to the RPR test, are shown in Fig. 3. The RPR titer (R values) is determined according to the highest serum dilution which still displays adequate flocculation in the presence of the antigen in the RPR test with higher dilutions implying higher reactivity.14 A higher R value implies a greater number of antibodies present in the serum, serving as a measure of the relative activity of an infection. The results demonstrate a strong correlation between the RPR titer and the measured BSI signal for assays with all three antigens, indicating the potential of BSI to be used to measure antibody levels in patient samples.

Collectively, these experiments demonstrate that BSI is capable of serving as a reactive serum immunodiagnostic assay system in a clinical setting with the potential to quantitatively assay clinical samples. Additionally, the ability to achieve congruent BSI results using significantly different antigen preparations, namely a lipoprotein (r17) and essentially a lipid (cardiolipin), highlights the versatility of BSI inmeasuring antibody–antigen interactions in human sera and the possibility of multiplexing BSI assays to streamline diagnostic approaches for syphilis and other diseases which employ antibody detection assays.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes for Health (R01 EB003537-01A2), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (200-2009-M-29719), and the Vanderbilt University Institute of Chemical Biology.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Details of experimental procedures and instrumental setup. See DOI: 10.1039/c0an00098a

Notes and references

- 1.Bornhop DJ. Appl Opt. 1995;34:3234. doi: 10.1364/AO.34.003234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markov DA, Dotson S, Wood S, Bornhop DJ. Electrophoresis. 2004;25:3805. doi: 10.1002/elps.200406139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorensen HS, Pranov H, Larsen NB, Bornhop DJ, Andersen PE. Anal Chem. 2003;75:1946. doi: 10.1021/ac0206162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swinney K, Bornhop DJ. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:613. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200202)23:4<613::AID-ELPS613>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang ZL, Bornhop DJ. Anal Chem. 2005;77:7872. doi: 10.1021/ac050752h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bornhop DJ, Latham JC, Kussrow A, Markov DA, Jones RD, Sorensen HS. Science. 2007;317:1732. doi: 10.1126/science.1146559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kussrow A, Kaltgrad E, Wolfenden ML, Cloninger MJ, Finn MG, Bornhop DJ. Anal Chem. 2009;81:4889. doi: 10.1021/ac900569c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Latham JC, Stein RA, Bornhop DJ, Mchaourab HS. Anal Chem. 2009;81:1865. doi: 10.1021/ac802327h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Domeika M, Litvinenko I, Smirnova T, Gaivaronskaya O, Savicheva A, Sokolovskiy E, Ballard RC, Unemo M. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1094. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polifke T, Rauch P. Genet Eng Biotechnol News. 2008;28:43. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daskalakis D. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2008;5:72. doi: 10.1007/s11904-008-0012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golden MR, Marra CM, Holmes KK. JAMA, J Am Med Assoc. 2003;290:1510. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.11.1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kent ME, Romanelli F. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:226. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larsen SA, Pope V, Johnson RE, Kennedy EJ Jr, editors. A Manual of Tests for Syphilis. 9. American Public Health Association; Washington DC: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsen SA, Steiner BM, Rudolph AH. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:1. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sambri V, Marangoni A, Eyer C, Reichhuber C, Soutschek E, Negosanti M, D’Antuono A, Cevenini R. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8:534. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.3.534-539.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.