Abstract

The cell membrane deforms during endocytosis to surround extracellular material and draw it into the cell. Results of experiments on endocytosis in yeast show general agreement that 1) actin polymerizes into a network of filaments exerting active forces on the membrane to deform it, and 2) the large-scale membrane deformation is tubular in shape. In contrast, there are three competing proposals for precisely how the actin filament network organizes itself to drive the deformation. We use variational approaches and numerical simulations to address this competition by analyzing a meso-scale model of actin-mediated endocytosis in yeast. The meso-scale model breaks up the invagination process into three stages: 1) initiation, where clathrin interacts with the membrane via adaptor proteins; 2) elongation, where the membrane is then further deformed by polymerizing actin filaments; and 3) pinch-off. Our results suggest that the pinch-off mechanism may be assisted by a pearling-like instability. We rule out two of the three competing proposals for the organization of the actin filament network during the elongation stage. These two proposals could be important in the pinch-off stage, however, where additional actin polymerization helps break off the vesicle. Implications and comparisons with earlier modeling of endocytosis in yeast are discussed.

Introduction

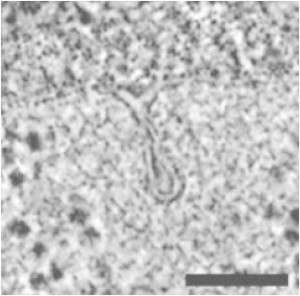

Endocytosis is the process by which extracellular agents are ingested by the cell as a result of the cell membrane surrounding and engulfing them (1). The membrane then pinches off to form a vesicle that encloses the now intracellular material. Fig. 1 presents an electron micrograph image of a deformed cell membrane near pinch-off in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (2). Experiments have identified a handful of core proteins, although there are upward of 50 proteins participating in the endocytotic machinery (3–5). Live-cell imaging of these fluorescently labeled core proteins provide us with a sequence of events for the endocytotic machinery (6,7). Though the composition and timeline of the endocytotic machinery are known, in yeast, there are competing proposals about how these few core proteins interact with the cell membrane to cause it to form a vesicle (8–10). We address these competing qualitative proposals by quantitatively comparing them.

Figure 1.

An electron micrograph image of a deformed membrane during endocytosis in S. cerevisiae. The image is reprinted with permission from Kukulski et al. (2). Scale bar, 100 nm.

According to experiments, the sequence of events in the endocytotic machinery in yeast is as follows (11,12). Clathrin is recruited to the invagination site (13), along with adaptor proteins, such as Sla1 and Ent1/2 (5). Sla1 and Ent1/2 proteins bind the clathrin to the membrane, and Sla2 proteins bind actin filaments to the membrane (5). Another protein, WASp, is also recruited to the site. WASp activates the branching agent Arp2/3, enabling a branched actin filament network to be generated near the invagination site (6). The growth of this network drives membrane tube formation. BAR proteins eventually become prominent and help facilitate pinch-off of the membrane (14). Fig. 2 illustrates this process using what will turn out to be Proposal 1 for the organization of the actin. The initial invagination due to clathrin and other adaptor proteins takes ∼1–2 min. In contrast, the time for the tube to form and pinch-off is only ∼10–15 s. The length/radius ratio of the tube before pinch-off is typically 7–10 (2) (Fig. 1).

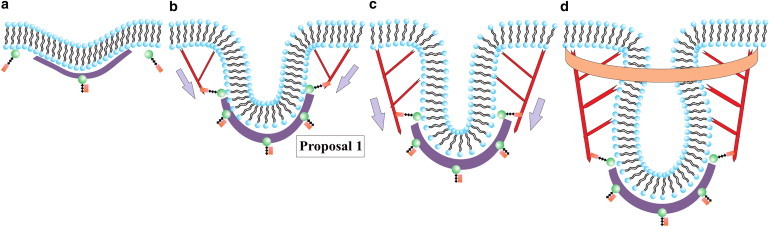

Figure 2.

Schematic for endocytosis in yeast using Proposal 1 for the actin filament organization. (a) Clathrin (purple) attaches to the membrane (black/blue) via proteins Sla1 and Ent1/2 (not depicted here) and the protein Sla2 (green/brown) is recruited near the clathrin. (b) Actin (red) attaches to the membrane near the edge of the clathrin bowl via Sla2 and lengthens due to polymerization to initiate tube formation. (c) Actin continues to polymerize and lengthen the tube. (d) BAR proteins (orange) become prominent and surround part of the tube (and the actin). Gray arrows denote the direction of the actin force on the membrane. Note that potential additional actin filaments rooted in the surrounding cytoskeleton and extending toward the invagination site have not been drawn.

The role of clathrin may be somewhat clear. The spontaneous curvature of individual clathrin molecules presumably helps initiate membrane deformation as the molecules indirectly attach to the membrane via adaptor proteins, with the initial deformation being rather small, in contrast to the deformation due to clathrin observed in mammalian cells. How the actin filament network reshapes the membrane, on the other hand, is less clear, since there are currently three competing proposals put forth by biologists as to how this is accomplished. The first proposal (Proposal 1) argues that the barbed/plus ends of polymerizing actin filaments are oriented toward the flat part of the membrane with the pointed/minus ends anchored just above the clathrin bowl (8). Proposal 2 argues that a collar-like structure of plus end filaments anchored to the rest of the cytoskeleton and oriented toward the neck of the deformation to elongate it and drive the pinch-off (9). Proposal 3 suggests that there are two regions of attachment of the actin filaments to the membrane such that two branched actin networks are generated (10). The two networks repel each other as they grow, because they cannot interpenetrate, and thus drive tube formation. See Fig. 2 b for a schematic of Proposal 1 and Fig. 3 for schematics of Proposals 2 and 3.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic depicting Proposal 2, where the actin filaments are tethered to the rest of the cytoskeleton, as denoted by the two black Xs, and polymerize inward toward the invagination site. (b) Schematic representing Proposal 3, where there are two local anchoring regions such that two actin networks form to drive tube formation. Gray arrows denote the direction of the actin force on the membrane.

Each of these three proposals for endocytosis in yeast assumes a unique organization for the actin filament network. Can any of these models be ruled out on the basis that they do not provide the forces required to deform the cell membrane that is consistent with observations? And what about the mechanism for pinch-off? Is there any underlying instability, or is there a more engineered approach, with the pinch-off occurring at some fixed distance from the top of the invagination? We approach clathrin-initiated endoctyosis in yeast by breaking up the sequence of fluid membrane deformations into three stages: 1) initiation, 2) elongation, and 3) pinch-off. In the process, we identify a mechanism that could assist in the pinch-off via a pearling-like instability, where surface tension competes with bending energy in cylindrical vesicles such that it is energetically favorable for long enough cylinders to break up into spheres. An instability-driven mechanism is potentially powerful given the ubiquitousness of endocytosis.

This proposed pearling-like instability mechanism will be contrasted with an alternative pinch-off mechanism put forth by Liu and colleagues (8,15). In that model, the cell membrane is also modeled as a fluid membrane—a two-component fluid membrane, where one component is the nonscission region and the other is the scission region. Physically, the two regions correspond to hydrolyzed and nonhydrolyzed PIP2 regions. The increasing interfacial line tension between the two components drives the pinch-off, which always occurs at some fixed distance from the top of the invagination site by construction, if you will. We will ultimately compare and contrast our model with that earlier model and compare our model with another, more recent, model in which the cell membrane is modeled as an elastic membrane with a nonzero shear modulus (16).

In mammalian cells, the two key players in endocytosis are clathrin and dynamin, a motor protein that drives the pinch-off in a system very different from that for yeast. Another difference between yeast and mammalian cells is the presence of a cell wall in yeast cells. This wall is needed to prevent lysis due to an internal turgor pressure, which can be as large as 106 Pa. It has been speculated that the presence of the turgor pressure biases the use of F-actin as an invagination tool (17). We will discuss the implications of turgor pressure for our model throughout this work.

This article is organized as follows. The next section introduces our cell membrane modeling approach to endocytosis, which is divided up into three stages, as mentioned previously, whereas the third section presents the resulting cell membrane configurations for each stage. We conclude by framing our results and discussing their implications.

Materials and Methods

We model the cell membrane as an ideal two-dimensional surface residing in three-dimensional Euclidean space. This surface represents the neutral surface of the physical membrane and approximately corresponds to the contact between the two leaflets of the lipid bilayer (18). Mathematically, this surface is parameterized by curvilinear coordinates (α1, α2) and is described by radius vectors . Using standard methods applicable to differential geometry of surfaces (19), we then define the mean (H) and Gaussian (K) curvatures of the surface.

The energy of a bare membrane depends on its curvature (20) and can be written as

| (1) |

where C0 is a spontaneous curvature, κ is the membrane bending rigidity, κG is the saddle-splay modulus, σ represents the surface tension, and dS represents the area of an infinitesimal element of the surface. Finally, p represents the turgor pressure present in yeast cells, with dV the infinitesimal volume element for any deformation from a flat surface.

Beginning with the above energy functional, which models the energy of the deformations of a bare cellular membrane, we systematically incorporate new physics associated with the three stages of endocytosis by allowing the parameters to be component-dependent or by adding new terms to the energy.

Initiation stage

Clathrin is one of the first proteins recruited to the endocytic site. Each clathrin molecule is a nonplanar triskelion that can pucker in the center (21). Due to the intrinsic curvature of clathrin molecules, they form a basket-like structure when they bind to each other. However, they require adaptor proteins, such as Sla1 and Ent1/2, to bind to the membrane (5,22). The binding process induces curvature in the membrane. The membrane rigidity may also be affected by protein binding. In fact, membrane rigidity depends on several factors, such as membrane lipid and protein composition, to account for the range of values (tens of kBT) reported in the literature (23).

We encode the effect of clathrin binding, via Sla1 and Ent1/2, to the cell membrane with effective parameters to characterize the model of the cell membrane. The clathrin indirectly binding to one side of the membrane induces spontaneous curvature in the membrane. Since the clathrin indirectly binds only to part of the membrane, we use a two-component membrane, with one component denoting the bare membrane and the other denoting the part of the membrane to which the clathrin is indirectly attached with nonzero spontaneous curvature. We also vary the bending rigidity of the part of the membrane to which the clathrin is indirectly attached.

The energy functional of the membrane for this initiation stage is given by (20)

| (2) |

where i = 1 denotes the Sla1/Ent1/2-bound membrane and i = 2 denotes the bare membrane.

Elongation stage

We now ask how the emergent actin network exerts additional deformations/forces on the membrane after the initiation of endocytosis. As shown in Fig. 2, the protein Sla2 is recruited to the invagination site before actin assembly. Sla2 binds to the clathrin and to the membrane near the clathrin, but according to Boettner et al. (5), Sla2 bound to the membrane near the top of the clathrin basket binds actin filaments. Since these Sla2 binding sites are near the top of the clathrin basket, i.e., butting up against the elastic clathrin basket, they provide localized binding/anchoring of the actin filaments to the cell membrane. Assuming that the minus end of the actin filament anchors to the cell membrane via Sla2, the plus end then polymerizes upward and ratchets against the cell membrane. The asymmetry between anchoring at the minus end and ratcheting at the plus end provides a time-averaged force to invaginate the membrane further into the cell. Actin filament nucleation via Arp2/3 increases this force.

We therefore model the actin filament network as an applied force on the membrane localized at these Sla2 anchoring points. The magnitude of this force is related to the total number of actin filaments participating in the network, and this number has been computed based on a combination of experimental data and kinetic modeling (24,25). We use the final configuration of the emergent actin network to determine the force applied to the membrane. Given the observed tubular structure of the deformation, this actin force is assumed to be axisymmetric, with constant components in the radial and −z (downward) directions, i.e., . The actin force is imposed by adding a linear potential of the form Vact(ρ,φ,z) = −(Fρρ + Fzz) to the energy for the part of the membrane to which the force is locally applied. The energy functional for the elongation stage is

| (3) |

where g(ρ,φ,z) = 1 for the region over which the actin force is applied and zero otherwise. To distinguish between Proposals 1, 2, and 3, we explore different anchoring regions and different ratios of the force components. Note also that Vster(ρ,φ,z < 0) = ∞ for ρ > Rap and zero otherwise. This models the accumulation of the yeast actin cytoskeleton just beneath the cell membrane and near the tubular invagination as it emerges (9,26). The ρ > Rap,z > 0 region acts as a reservoir for tube growth. We therefore impose an additional quadratic potential, Vpin(ρ,z) = (1/2) βz2 for ρ > Rap, where β is chosen so that the membrane outside this region remains flat.

Pinch-off stage

Experiments indicate that the BAR proteins dominate in this last stage, after the tubule-like deformation forms (2,15). This observation is rather perplexing, since BAR proteins, which themselves are curved, can sense and generate spontaneous curvature in the cell membrane (27). In other words, why does actin, and not the BAR proteins, play the dominant role in generating the tubule-like deformation? We suggest that once a tubule-like deformation occurs, the BAR proteins surround and confine the tube-plus-actin filament network near the top of the invagination site (see Fig. 2 d) to stop actin polymerization. The BAR proteins only sense curvature here; they do not generate it. Since actin polymerization is driven by a ratcheting effect in a spatially fluctuating membrane, when these spatial fluctuations are suppressed, actin polymerization stops. When the polymerization stops, no more membrane material can become part of the tube. In other words, the membrane tube area remains constant. With the BAR proteins confining the top part of the actin filament network against the membrane to couple the network to the membrane, we introduce an additional energetic term to the system. Now that the actin network has developed, we model it as an underlying elastic network of springs. Because the actin network is now connected to the membrane (as opposed to ratcheting against it in the elongation stage), the filament tips of the spring network depend on the configuration of the membrane. As with any elastic network coupled to a fluid membrane, the BAR-protein-plus-actin-filament contribution to the energy of a now cylindrical membrane is (28)

| (4) |

where μ is the spring constant and i,j denote the meshwork coordinates of the springs on the surface of the membrane. Since the tube has now been formed, we will study the cylinder membrane described by Eq. 1 with this additional energy, EBAR+actin. This energy will turn out to raise the surface tension of the membrane. This calculation will also suggest a new pearling-instability pinch-off mechanism for endocytosis in yeast.

Methods

We utilize both analytical and numerical techniques to study the above model. On the numerical side, we use simulated annealing Monte Carlo (MC) simulations to identify low-energy structures. In our simulations we represent the membrane using standard techniques for constructing discrete surface triangulations (29). The discrete version of the bending energy described by Eq. 2 is then implemented using expressions introduced by Brakke (30). The mean curvature at vertex i is given as Hi = (1/2)(Fi⋅Ni/Ni⋅Ni), with Fi being the gradient of area and Ni the gradient of volume calculated with respect to the coordinates of vertex i. The bending energy is then given as Ebend = (H − C0)2Ai/3, where Ai is the total area of triangles sharing vertex i. The spontaneous curvature C0 is chosen according to the region of the membrane to which the vertex belongs. Surface tension is computed as an energy penalty to change the reference area of the membrane. Reference area A0 is chosen to be that of the initial flat configuration. The energy associated with changes of the surface area is then Esurface = σ|A − A0|, where A is the area associated with a vertex and computed as one-third of the sum of the areas of all triangles sharing that vertex.

To ensure that we simulate a fluid membrane, each MC step involves two steps (29): 1) displacement of a vertex in a direction chosen at random uniformly from a cube [−0.05l0, 0.05l0]3, where l0 is the average edge length of the initial triangulation, and 2) flipping an edge on a rhombus. This flip removes an edge shared by two triangles and reconnects it so that it spans the opposite, previously unattached, vertices (31,32). Moves are accepted or rejected according to the Metropolis algorithm. The sweeps are continued until the total energy does not change with some prescribed precision. Different random numbers of generator seeds are used to ensure the reproducibility of the lowest energy configurations. A typical run with Nv ≈ 3.5 × 103 vertices consists of ∼106 MC sweeps, with a sweep consisting of attempted moves of each vertex and attempted flips of each edge. Any moves or edge flips leading to unphysical self-intersection of the triangulation are rejected. This is achieved by endowing each vertex with a hard core of diameter b = 0.9l0, and each edge with a tethering potential (29) with maximum length lmax = 1.4l0 such that lmax/b ≈ 1.55. These values are chosen, in accordance with the methods of Gompper and colleagues (33,34), to be tight enough to prevent edge crossings but still loose enough to allow edge flips, thus ensuring fluidity. Finally, the actin forces are applied to the vertices.

Results

Initiation stage with clathrin

To analyze the equilibrium shapes of the membrane in the initiation stage, we use the Monge representation such that each coordinate on the membrane in three-dimensional space is parameterized by two planar coordinates, x and y, with . We then assume axial symmetry, so that . In the small-gradient approximation, Eq. 2. simplifies to

| (5) |

where A is the area of domain 1 (the Sla1/Ent1/2 bound component that is attached to the clathrin basket), and σ0 is a Lagrange multiplier introduced to fix the area of domain 1 (see Supporting Material). We have also introduced a line tension, γ, at the interface between the two components, i.e., the bare component and the Sla1/Ent1/2 bound component. (Note that Ent1/2 are the yeast homologues for epsin in mammalian cells.) Finally, the radial coordinate of the interface is denoted by R1, whereas R2 denotes the outer edge of the membrane. We neglect the turgor pressure for now and address it toward the end of this subsection.

We now proceed with the variation of the Lagrangian, (see Supporting Material). As for boundary conditions, we constrain the membrane to be continuous at the interface between the two components, so that z1(R1) = z2(R1) = z(R1). In addition, for the bending energy to remain finite, so that , the membrane cannot have ridges. For R2 → +∞, we have z2(R2) = 0, so that . The radial symmetry demands that . With these conditions, , and δz1(0) are free variables, so the energy is minimized by solving the equations

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

Solving Eqs. 6 and 7 leads to

| (12) |

where , and I0 and K0 denote the zeroth-order modified Bessel functions of the first and second kind. We can then use Eqs. 8–11 and the boundary conditions to determine these eight coefficients, as well as σ0 and R1.

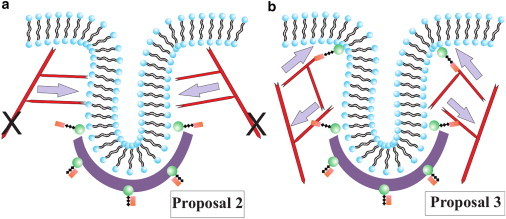

For typical parameters for the two-component membrane, we use κ1 = 20 kBT (35), κ2 = 10 kBT (23), C01 = 0.1 nm−1 (36), C02 = 0, κG1 = −0.83κ1 (37), κG2 = −0.83κ2, σ1 = 0.18 kBT/nm2 (38), σ2 = 0.18 kBT/nm2 (38), A = π100 nm2, and γ = 3 kBT/nm (39). Given these parameters, the equilibrium shape of the membrane is plotted in Fig. 4 a. We see that a dimple emerges due to clathrin binding. This dimple finalizes the initiation stage of endocytosis in yeast and sets the radius of the imminent tubular invagination. Fig. 4 a contains two additional curves to assess the effect of nonzero Gaussian rigidity, κG. In a previous work, it was found that differences in κG across a boundary can drive tube formation in membranes (40). We find, given the above parameters, that it is the nonzero spontaneous curvature that instead drives the dimple formation. More precisely, for C01 = 0, no dimple forms, and for nonzero C01 and κG, the depth of the dimple is enhanced only by ∼14%.

Figure 4.

(a) Cell membrane profile, or z(x,y = 0), for the parameters stated in the text. The red area denotes the clathrin-bound part of the membrane, and the blue denotes the bare membrane. (b) Top view of the two-component membrane model using simulated annealing Monte Carlo methods. (c) Side view of the same configuration. Both images have been rescaled accordingly for presentation purposes. (d) Comparison of the maximum depth (or depth) obtained from the numerical simulation (symbols) with the analytical solution (line) for the intiation stage. All the parameters, except for the varying C01, are the same as the κG = 0 curve in a. To see this figure in color, go online.

Before concluding this subsection, we must point out that our method differs from an earlier two-component dimple analysis (41). First, Ursell et al. (41) do not take into account the term (42), which is needed for consistency in the small-gradient expansion. Second, we take into account nonzero κG, because κ1 ≠ κ2. Third, to solve for some of the coefficients, the earlier work imposes mechanical equilibrium conditions, as opposed to direct implementation of boundary conditions in the variation of the Lagrangian.

Let us now address the presence of turgor pressure. Previous models have used anywhere from 103 Pa (8,15) to 105 Pa (16), since the turgor pressure at an endocytotic site has not been measured directly. The turgor pressure could be lowered locally by a release of osmolytes near the endocytotic site, as proposed in Carlsson and Bayly (16) based on experiments presented in Tamás et al. (43). For the above set of parameters, using a turgor pressure of p = 104 Pa, the energy contribution from the turgor term is 20% of the total energy in the absence of the turgor pressure, so that the depth of the dimple will decrease slightly. For p = 103 Pa, the turgor energy is only 2% of the total energy in the absence of the turgor pressure and can be neglected, whereas for p = 105, a different parameter range would need to be explored, such as the nonzero value of the spontaneous curvature of the membrane, the effect of which will be described below. Of course, even in the absence of turgor pressure, a depth of 7.7 nm is small, such that it may be difficult to measure given an electron microscope pixel size of 2.53 nm (2). The presence of 104 Pa turgor pressure further decreases this depth. Thus, the membrane may not be perfectly flat when the actin filaments begin to polymerize, as speculated by Kukulski et al. (2).

We also conduct numerical minimization of the intiation stage (Fig. 4, b and c). As a check on our simulations, we compare the maximum depth of the dimple, i.e., |zmax(r)|, as a function of C01, for the analytical calculation with that for the numerical calculation in Fig. 4 d. Here, each energy relaxation is performed starting from a flat configuration. We place a flat patch of radius R2 = 40l0 on a hard plane parallel to the xy plane. We then assign spontaneous curvature C01 to all vertices in the central region of radius rC01 = 6l0. We use the energy functional in Eq. 2 with an additional interfacial line tension. Fig. 4 d shows the output of the simulation for the same parameters used in Fig. 4 a, except with additional C01 values. We find very good agreement between the two. Note that since nonzero κG does not drive the dimple formation (for the parameters studied), we do not include it here.

Elongation stage via actin polymerization

Now that the initial small deformation due to Sla1/Ent1/2 binding the membrane to the clathrin basket is formed, the overall radius of the tubular invagination is set. The protein Sla2 next binds to and near the clathrin dimple. Only those Sla2 molecules bound near the top of the clathrin dimple also bind to the actin to form a ring-like structure of binding sites (5). Since the clathrin dimple is elastic-like, it impedes motion of the Sla2 molecules near the top of the clathrin dimple such that these Sla2 binding sites provide for an anchoring of the actin filaments to the membrane to which a localized force can be exerted. As the actin filaments polymerize, the interaction of the polymerizing actin filament tips with the membrane is much more dynamic than the anchoring points since actin filaments polymerize via a ratcheting effect. The membrane just provides a constraint for the growing filament tips to ratchet against along the length of the tube. This asymmetry in the force is needed for a deformation (due to other than a random fluctuation) to occur. Thus, we model the effects of both the anchored and polymerizing ends of actin filaments as a localized force on the membrane via the potential Vactin, as indicated in Eq. 3. In addition, the steric potential Vster models the accumulation of the yeast actin cytoskeleton just beneath the cell membrane and near the tubular invagination as it emerges (9,26).

How large is this force? An estimate can be obtained from quantitative confocal microscopy measurements of 16 fluorescently labeled proteins involved in endocytosis in fission yeast (24). The mean peak for the number of G-actin molecules (monomeric actin) is ∼7500. Assuming that all of these molecules polymerize to form actin filaments of ∼100 nm in length (25) and that each G-actin molecule is 2.7 nm in length (5 nm in diameter) then each filament contains ∼40 molecules. About 200 actin filaments would then be formed. Each actin filament contributes ∼1 pN of force, since the stalling force of an individual actin filament is ∼1 pN (44). The total force is then ∼200 pN, which is applied to the anchoring region of the actin filaments. Since we do not take into account dynamics explicitly, we will merely implement the final value of the total force rather than increasing the force as the actin network develops. In the quasistatic limit, the two approaches should be equivalent.

We now turn to the direction of the actin polymerization force and review the three different proposals for actin filament orientation (9,10,15). As shown in Fig. 2, actin filaments polymerize upward and branch via Arp2/3 to drive the membrane farther into the interior of the cell. In Proposal 1, the force is predominantly downward, as opposed to radially inward, provided the initial actin filaments are aligned <45° relative to the normal of the undeformed membrane. Assuming that the orienation of the anchored actin filaments stays relatively fixed as branched actin filaments are generated, then the magnitude of the total actin force increases while remaining fixed in direction. Here, we assume axial symmetry so that there are only two nonzero components of the total force.

How do the competing Proposals 2 and 3 compare with Proposal 1? In Proposal 2, the actin network grows inward from the outerlying cytoskeleton toward the invagination site. The actin network is anchored to the outerlying cytoskeleton, as opposed to the cell membrane, via Sla2. If we assume a purely radially inward force, then the membrane will not deform into a tube with the observed length/radius ratio of ∼10. The branched structure of the actin network, however, can provide a downward component to the total force to elongate the tube (Fig. 3 a). We therefore distinguish Proposal 1 as a case where the downward component of the total polymerization force is smaller than the radially inward component, whereas Proposal 2 is the reverse case.

Proposal 3 assumes that there are two anchoring zones for actin filaments—one toward the bottom of the emerging tube and another near the top of the tube. From these two anchoring zones emerge two actin networks simultaneously growing toward each other and thus repelling each other, since the actin filaments cannot interpenetrate (Fig. 3 b). It is this repulsion that presumably elongates the tube. Coexistence of a downward force component and an upward force component, however, demands that the membrane simply stretches like a rubber band with no new cell membrane material being added to the tube. Because the cell membrane formation is dominated by bending (and not stretching), deformation of the membrane by actin under Proposal 3 would presumably lead to rupture of the tube (45). It is not as likely that Proposal 3 contributes to membrane tube formation, and we do not study it further as an elongation mechanism.

Thus, we focus on Proposals 1 and 2 for the elongation stage, referring to them as Models 1 and 2, respectively, and study them quantitatively. To gain some insight, we first review a slightly simpler model, again first in the absence of turgor pressure. Consider a bare (one-component) membrane with downward force F applied just to the origin, as opposed to being applied over an extended region of the membrane (46). Assume that the membrane has bending rigidity κ and surface tension σ. For a cylindrically shaped membrane with length L and radius R, surface tension favors reducing the radius of the cylinder/tube, whereas bending favors a larger radius. Upon minimizing the energy, one obtains an equilibrium radius of and an equilibrium force of . For forces <Feq, the membrane deformation is a wide-necked depression and reaches some equilibrium depth that depends on the force, whereas for forces >Feq there is a first-order transition to a cylindrical shape of arbitrary length. Simulations of the membrane-shape equation indicate that there is a force barrier from the wide-necked depression to cylinder formation that is 13% larger than Feq (46). Barriers are a characteristic signature of first-order transitions. Monte Carlo simulations of pure downward pulling on a membrane over an extended region (as opposed to a single point) support this scenario with the force barrier increasing linearly with the size of the region over which the force is exerted (47).

Now consider Models 1 and 2 with an additional radially inward force and a steric interaction between the membrane and the actin. To begin, we expect the radially inward force to increase the force barrier to arbitrarily long cylindrical formation. We also expect the steric interaction to alter the transition, since Rap cuts off the wide-neck depression and makes it easier to crossover to long cylinder formation. More specifically, we expect that as Rap decreases, the change from noncylindrical to cylindrical occurs at a lower applied force. This effect has been observed in Monte Carlo simulations of driving fluid vesicles through a pore (48).

To test these notions, we study the extension-force curve of tube/cylinder formation for the various models. We do so numerically, because Vact (Eq. 3) is a potential localized to a particular region of the membrane, which would be difficult to handle analytically. We first apply a purely downward force to a ring of vertices right above the Sla1/Ent1/2 attached part of the membrane. We dub this Model 0. The magnitude of the total force is denoted by Ft and is distributed uniformly among the vertices. Since κ1 = 10 kBT and σ = 0.18kB T/nm, Feq ≈ 49 pN(for the applied point force). To numerically determine Feq0, the Feq equivalent for Model 0, we pull on the ring with initially 50 pN of total force, Ft, and Rap = 15 nm. We then reinitialize Ft to take on smaller values and look for the Ft at the boundary between tubes becoming shorter and tubes becoming longer. Using this algorithm, we find that Feq0 ≈ 25 pN. To study the force barrier, we find that deformations for Ft < 30 pN are reasonably robust to perturbations (stepping Ft up and back down again) such that 30 pN is a lower bound for the barrier. See Fig. 5 b.

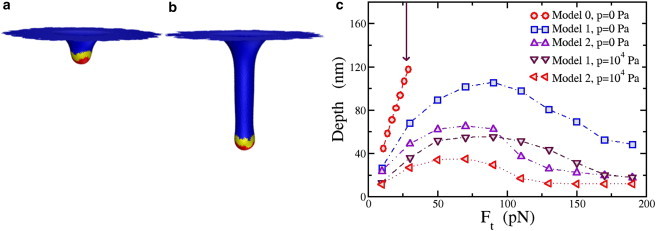

Figure 5.

(a) Simulation results for Model 1 with total applied force Ft = 10 pN. The total force is applied to only the yellow part of the membrane (at the vertices). Red denotes the Sla1/Ent1/2 bound part of the membrane and blue denotes the bare membrane. (b) Same as (a), but with applied force Ft = 50 pN; (c) Comparison of the depth as a function of Ft for three different models with zero and nonzero turgor pressure, p. Again, the error bar is of the order of the symbol size. The arrow pointing downward denotes the value of Feq for reference. To see this figure in color, go online.

We now add a radially inward force component to the force applied to the ring of vertices to address Models 1 and 2. How does this radially inward force modify the shape crossover due to the downward component of the force? For a purely radially inward force applied to the ring of vertices, the membrane will pucker inward where the force is applied and no cylindrical tube will form. The additional radially inward force increases the force barrier to long tube formation. In Model 1, the actin filaments are anchored at the bottom of the tube, so that the downward component of the force is larger than the radially inward component. We assume that , which would correspond to actin filaments anchoring at an angle of ∼35° with respect to the normal of the flat part of the membrane. In Model 2, the radially inward component of the actin polymerization force is larger than the downward component, so we choose .

Fig. 5 c depicts the depth-versus-total force curve for both models, as well as two membrane configurations for Model 1. The tubes are reasonably robust to perturbations for all forces studied, suggesting that the crossover to long cylinders is not made. Even though the downward component of the force is increased, it is not enough to overcome the increasing force barrier introduced with the increasing radially inward force as well. For large enough radially inward forces, the tube depth begins to decrease, resulting in a nonmonotonic depth-versus-total-force curve. As the contribution of the radially inward force increases, it is energetically more favorable for the membrane to deform inward than to elongate vertically. Fig. 5 d depicts two equilibrium configurations for Model 1. For the values of Rap studied, 12 − 18 nm, the tube depth increases only by several percent with increasing Rap. In other words, the applied force clearly plays the dominant role.

Now to Model 2. All tubes are reasonably robust to force perturbations, just as in Model 1, and the depth-versus-total-force curve is also not monotonic. The largest depth of the membrane deformation for Model 2 is ∼65 nm. Although there is indeed some room to play with the ratio of the magnitude of the two components, we contend that Model 1 may better account for the range of observed tube depths (2). Hindsight tells us that Model 1 would be more reasonable for obtaining longer tubes, but such depths could have been much longer than the observed ones. The nonmonotonicity suggests an optimal force of ∼100 pN, should long tubes be the optimizing principle. And although Model 2 may not necessarily act as the initial driving force to elongate the tube, we address an important role for Model 2, and one aspect of Proposal 3, during the final stage of endocytosis.

To investigate the role of turgor pressure in Models 1 and 2, we find that as the turgor pressure increases to 103 Pa, our previous results are robust. However, for turgor pressures >103, the tube depths (for a given total force) decrease (see Fig. 5 c). Thus, the presence of large turgor pressure biases Model 1 even more. However, for p = 104 Pa, since the largest depth is ∼55 nm, to account for larger observed depths, one can invoke the presence of myosin I to allow for extra downward force to increase the depth of the tube (49,50). Myosin I binds the membrane to the actin filaments. It has been estimated that there are ∼300 myosin I molecules at each endocytotic site, each exerting 2 pN of force (51) (assuming that myosin I carries the same force-generation potential as myosin II) to arrive at a maximal downward force of 600 pN. Such an additional downward force component would allow for long tubes even in the presence of larger (104–105 Pa) turgor pressures.

Pinch-off stage via the pearling instability

Experiments indicate that the BAR proteins enter in this last stage, after the actin filament network has formed (2,15). Yet many qualitative depictions of the process show the BAR proteins in between the membrane and the actin filament network (15). It has been shown that BAR proteins generate spontaneous curvature in membranes (27). Since the BAR proteins enter after the tube has formed (2,15), there is no need to generate spontaneous curvature, only to sense it. We suggest a potentially new role for BAR proteins here, beyond simply sensing curvature. Once the tubule-like deformation via the actin filament network occurs, the BAR proteins surround and confine the tube-plus-actin-filament network toward the top part of the tube, where bare membrane is exposed to the BAR proteins (Fig. 2 d). When the actin filament network is surrounded and the fluctuations of the bare membrane are suppressed, actin polymerization stops, since polymerization is driven by a ratcheting effect in spatially fluctuating fluid membrane (and by the entropically elastic actin network (52)). When actin polymerization stops, no more material can become part of the tube, and the membrane tube area remains constant.

Because BAR proteins confine part of the actin filament network, it is now restricted to lie on the membrane. This effect will generate a new contribution to the membrane energy, as indicated in Eq. 4, where the coordinates of the network are the coordinates of the membrane. The actin filament network is modeled as an elastic network with spring constant μ (28). Since actin filaments are semiflexible polymers with a persistence length of ∼20 μm, the elasticity comes from elasticity of the Arp2/3, the branching agent responsible for nucleating new filaments. The entropic angular spring constant for Arp2/3 is approximately 10−19 J/rad2 (53), so for branches several actin monomers long, the entropic linear spring constant, μ ≈ 10−2 N/m, or 2.5 kBT/nm2. This additional elasticity contributes to the membrane surface tension, with the effective membrane surface tension becoming σeff = σ + μ/2, at lengthscales larger than the mesh size of the actin network.

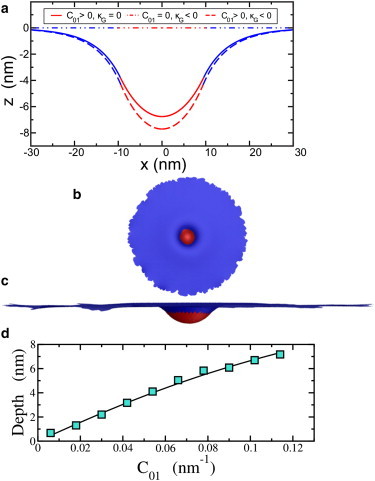

How does this increase in surface tension affect the membrane + actin + BAR-protein system? We investigate configurations of a cylindrically shaped membrane with bending rigidity κ and increasing surface tension to answer this question. Could such an increase lead to destabilization of the cylindrically shaped membrane? As the surface tension increases, a sinusoidal perturbation may perhaps lead to the cylindrical membrane breaking up into spherical droplets, as surface tension favors spheres. This mechanism is otherwise known as pearling instability (54,55).

Is this instability relevant to the system at hand? Analytical analysis of this instability is included in the Supporting Material to address this question. This analysis suggests that the pearling instability may be relevant to the system at hand given the physiological parameters. For the relevant range of wavevectors (<0.1 nm−1), the cylinder is only stable when , where R0 = 8.71 nm, the original radius of the unperturbed cylinder, and κ = 10 kBT. The length/radius ratio of the initial cylinder is 10. This inequality, however, depends on the strength of the perturbation.

To analytically investigate the pearling instability, the volume is assumed to be constant, such that the turgor pressure is not important (see Supporting Material). This constraint is imposed so that the membrane does not shrink to a point once the surface tension term dominates. Although the invagination is indeed an open system so that the volume of the tube may change slightly, as long as the volume remains finite, a pearling instability can set in for some range of parameters. Pearling instabilities have been experimentally observed in open tubes in vivo and in vitro (56,57).

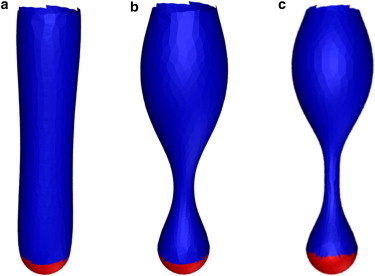

We implement numerical simulations to numerically test for this instability. We start an initial configuration of a triangulated capsule (as opposed to a cylinder) with the above parameters and then vary σ. As indicated in Fig. 6, the pearling instability mechanism sets in once is large enough. In this case, the surface tension must increase by an order of magnitude for the instability to set in. This increase by an order of magnitude is precisely the contribution of the Eact+BAR term in the energy increasing the surface tension from σ ≃ 0.1 kBT/nm2 to σ ≃ 1 kBT/nm2!

Figure 6.

(a–c) The pearling instability for a cylindrical membrane with increasing surface tension going from left to right, or and 4.15 respectively. The top and red parts of the tube are fixed.

Once the membrane breaks up into spheres, the spheres remain connected, as observed in experiments (54,58). This observation differs from the Rayleigh-Plateau instability, where the spheres do not remain connected. So how does the vesicle nearer to the interior of the cell break off from the upper part of the tubular membrane? The most natural answer would be via actin polymerization. Proposals 2 and 3 both provide mechanisms for some downward-directed actin polymerization on the vesicle to drive it further into the cell. In Proposal 2, actin filaments polymerizing inward from the surrounding actin cytoskeleton toward the invagination sites can facilitate break-off of the vesicle by making a comet tail behind it. Such an actin comet tail has indeed been observed in experiments (9). In Model 3, regions of actin filaments anchored to the membrane near the top of the invagination region while elongation is occurring could initiate downward actin polymerization. These filaments can then also drive the break-off of the vesicle nearer to the interior of the cell from the top sphere. Both routes may be important for the final break-off of the vesicle.

Discussion

We have developed and analyzed a quantitative three-stage model for endocytosis in yeast that is consistent with the experimental data (12). We first built a model for the initial small membrane deformation due to clathrin indirectly binding to the membrane via Sla1/Ent1/2. We demonstrated that the Sla1/Ent1/2-bound domain initiates invagination of the membrane by forming a small depression, or dimple, to set the radius of the subsequent tubular invagination. The subsequent tubular invagination is driven by actin polymerization forces, which we model as an external force applied to the membrane. We found that of the three competing proposals in the literature for the orientation of the actin filaments in driving tube formation, one proposal (Proposal 1) (15) is most likely to account for the observed tubular lengthscales of the cell membrane in endocytosis in yeast (2). For turgor pressures <103 Pa, our results predict the applied force that optimizes the length of the tube, where the largest length/radius ratio is ∼10. For turgor pressures >103 Pa, myosin I, an actin motor that binds directly to the cell membrane so that it can enhance actin-dependent forces on the membrane, may account for the large length/radius ratio (49). The combination of this large length/radius ratio and the effective surface tension increasing due to the presence of BAR proteins confining the actin filament network against the tubular cell membrane (Fig. 2 d) naturally leads to a pearling instability to potentially assist in the scission mechanism. We showed that by both analytical calculations and simulations, given the physiological parameters involved in endocytosis in yeast, a pearling instability may indeed promote spherical vesicle formation.

Let us contrast our model with an earlier model for endocytosis in yeast (8,15). In the latter study, the coordinated effect of protein-induced lipid phase segregation along the tubule plays a key role in vesicle scission. The phase separation between hydrolyzed and nonhydrolyzed PIP2, a membrane-bound protein to which actin attaches, calls for a two-component fluid membrane and induces an interfacial line tension between the two components to drive pinch-off. The effect of actin in that model (15) is to decrease the effective surface tension of the membrane, which makes it easier for the interfacial line tension to scission the membrane and is rather different from the effect of actin in our model. We, in contrast, model the actin as an applied force and are able to generate tube formations as a result. The competing quantitative model is not able to generate tubes explicitly given the manner in which actin polymerization is incorporated into the model. We also demonstrate that the pearling instability could potentially facilitate pinch-off. The frequency of endocytosis in budding yeast, invaginating its total cell membrane surface in ∼100 min (2), suggests that an instability, as opposed to a coordinated effort involving lipid phase separation, would be useful. The observation that scission occurs at a range of invagination depths also favors an instability as opposed to a more regulated mechanism. Comparison with another recent model is rather difficult, since the newer model assumes that the cell membrane is an elastic membrane with a nonzero shear modulus rather than a fluid membrane (16). The formation of tubes in elastic membranes is very different from the formation of tubes in fluid membranes, where there is no shear modulus.

Here, we have presented a quantitative model for endocytosis in yeast, but how much of this story applies to endocytosis in mammalian cells? More sphere-like membrane deformations are generated in mammalian cells due to clathrin cage formation and the motor protein, dynamin, driving pinch-off. Many of the same proteins involved in yeast clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) are conserved in mammalian CME (4). It could be that the presence of the turgor pressure in yeast makes clathrin cage assembly difficult, but clathrin basket assembly less difficult, given the much smaller change in volume for the basket. Then it is up to the actin and other proteins to finish the job. As some of our results depend on the strength of the turgor pressure, it would be good to measure it directly at an endocytotic site. There is also another route to endocytosis in mammalian cells via the CLIC/GEEC pathway, which does not require clathrin or dynamin and forms more tubular deformations, as observed in yeast (59). The requirement for actin in mammalian CME has been less clear. Several new studies in mammalian cells provide support for an actin requirement in the invagination and late stages of CME (4). On the other hand, a recent in vitro experiment with clathrin and dynamin suggests that these two proteins are sufficient to drive endocytosis in mammalian cells (60). In light of this experiment, it would be interesting to revisit the modeling of endocytosis in mammalian cells (61). It may also be useful to investigate how the modeling presented here can be extended to envelop virus entry (62), exocytosis, and budding to form a more unified theoretical framework for cell membrane deformations used to transport material in and out of the cell.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge helpful discussion with R. Bruinsma and J. Guven.

The authors also acknowledge support from the Soft Matter Program at Syracuse University and the Aspen Center for Physics, where part of this work was completed. M.J.B. acknowledges support from National Science Foundation grant DMR-0808812. J.M.S. acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation under Grant No. PHY-1066293. J.M.S. acknowledges NSF-PHY-1066293 and the hospitality of the Aspen Center of Physics, where part of this work was completed.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Lodish H., Berk A., Matsudaira P. 6th ed. W. H. Freeman; New York: 2007. Molecular Cell Biology. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kukulski W., Schorb M., Briggs J.A.G. Plasma membrane reshaping during endocytosis is revealed by time-resolved electron tomography. Cell. 2012;150:508–520. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMahon H.T., Boucrot E. Molecular mechanism and physiological functions of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;12:517–533. doi: 10.1038/nrm3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perrais D., Merrifield C.J. Dynamics of endocytic vesicle creation. Dev. Cell. 2005;9:581–592. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boettner D.R., Chi R.J., Lemmon S.K. Lessons from yeast for clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:2–10. doi: 10.1038/ncb2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaksonen M., Sun Y., Drubin D.G. A pathway for association of receptors, adaptors, and actin during endocytic internalization. Cell. 2003;115:475–487. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00883-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor M.J., Perrais D., Merrifield C.J. A high precision survey of the molecular dynamics of mammalian clathrin-mediated endocytosis. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J., Kaksonen M., Oster G. Endocytic vesicle scission by lipid phase boundary forces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:10277–10282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601045103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins A., Warrington A., Svitkina T. Structural organization of the actin cytoskeleton at sites of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:1167–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arasada R., Pollard T.D. Distinct roles for F-BAR proteins Cdc15p and Bzz1p in actin polymerization at sites of endocytosis in fission yeast. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:1450–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mooren O.L., Galletta B.J., Cooper J.A. Roles for actin assembly in endocytosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012;81:661–686. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060910-094416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaksonen M., Toret C.P., Drubin D.G. Harnessing actin dynamics for clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:404–414. doi: 10.1038/nrm1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baggett J.J., Wendland B. Clathrin function in yeast endocytosis. Traffic. 2001;2:297–302. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.002005297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawson J.C., Legg J.A., Machesky L.M. Bar domain proteins: a role in tubulation, scission and actin assembly in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:493–498. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu J., Sun Y., Oster G.F. The mechanochemistry of endocytosis. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlsson A.E., Bayly P.V. Force generation by endocytic actin patches in budding yeast. Biophys. J. 2014;106:1596–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aghamohammadzadeh S., Ayscough K.R. Differential requirements for actin during yeast and mammalian endocytosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:1039–1042. doi: 10.1038/ncb1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Safran S.A. Westview; New York: 2003. Statistical Thermodynamics of Surfaces, Interfaces, and Membranes. [Google Scholar]

- 19.do Carmo M. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs; NJ: 1976. Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helfrich W. Elastic properties of lipid bilayers: theory and possible experiments. Z. Naturforsch. C. 1973;28:693–703. doi: 10.1515/znc-1973-11-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirchhausen T., Harrison S.C., Heuser J. Configuration of clathrin trimers: evidence from electron microscopy. J. Ultrastruct. Mol. Struct. Res. 1986;94:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0889-1605(86)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reider A., Wendland B. Endocytic adaptors—social networking at the plasma membrane. J. Cell Sci. 2011;124:1613–1622. doi: 10.1242/jcs.073395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boal D.H. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, United Kingdom: 2012. Mechanics of the Cell. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sirotkin V., Berro J., Pollard T.D. Quantitative analysis of the mechanism of endocytic actin patch assembly and disassembly in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2010;21:2894–2904. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-02-0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berro J., Sirotkin V., Pollard T.D. Mathematical modeling of endocytic actin patch kinetics in fission yeast: disassembly requires release of actin filament fragments. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2010;21:2905–2915. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-06-0494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moseley J.B., Goode B.L. The yeast actin cytoskeleton: from cellular function to biochemical mechanism. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2006;70:605–645. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00013-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sorre B., Callan-Jones A., Roux A. Nature of curvature coupling of amphiphysin with membranes depends on its bound density. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:173–178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103594108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang R., Brown F.L.H. Cytoskeleton mediated effective elastic properties of model red blood cell membranes. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;129:065101. doi: 10.1063/1.2958268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gompper G., Kroll D.M. Triangulated-surface models of fluctuating membranes. In: Nelson D.R., Piran T., Weinberg S., editors. Statistical Mechanics of Membranes and Surfaces. 2nd ed. World Scientific; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brakke K. The surface evolver. Exp. Math. 1992;1:141–165. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kazakov V.A., Kostov I., Migdal A. Critical properties of randomly triangulated planar random surfaces. Phys. Lett. B. 1985;157:295–300. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Billoire A., David F. Scaling properties of randomly triangulated planar random surfaces: a numerical study. Nucl. Phys. B. 1986;275:617–640. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gompper G., Kroll D. Statistical mechanics of membranes: freezing, undulations, and topology fluctuations. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2000;12:A29–A37. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kohyama T., Kroll D.M., Gompper G. Budding of crystalline domains in fluid membranes. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2003;68:061905. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.68.061905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agrawal N.J., Nukpezah J., Radhakrishnan R. Minimal mesoscale model for protein-mediated vesiculation in clathrin-dependent endocytosis. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1000926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ford M.G.J., Mills I.G., McMahon H.T. Curvature of clathrin-coated pits driven by epsin. Nature. 2002;419:361–366. doi: 10.1038/nature01020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siegel D.P., Kozlov M.M. The gaussian curvature elastic modulus of N-monomethylated dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine: relevance to membrane fusion and lipid phase behavior. Biophys. J. 2004;87:366–374. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.040782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roux A., Cuvelier D., Goud B. Role of curvature and phase transition in lipid sorting and fission of membrane tubules. EMBO J. 2005;24:1537–1545. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baumgart T., Hess S.T., Webb W.W. Imaging coexisting fluid domains in biomembrane models coupling curvature and line tension. Nature. 2003;425:821–824. doi: 10.1038/nature02013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allain J.-M., Storm C., Joanny J.-F. Fission of a multiphase membrane tube. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004;93:158104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.158104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ursell T.S., Klug W.S., Phillips R. Morphology and interaction between lipid domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:13301–13306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903825106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Góźdź W.T., Gompper G. Shape transformations of two-component membranes under weak tension. Europhys. Lett. 2001;55:587–593. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tamás M.J., Luyten K., Hohmann S. Fps1p controls the accumulation and release of the compatible solute glycerol in yeast osmoregulation. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;31:1087–1104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kovar D.R., Pollard T.D. Insertional assembly of actin filament barbed ends in association with formins produces piconewton forces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:14725–14730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405902101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Evans E., Heinrich V., Rawicz W. Dynamic tension spectroscopy and strength of biomembranes. Biophys. J. 2003;85:2342–2350. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74658-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Derényi I., Jülicher F., Prost J. Formation and interaction of membrane tubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002;88:238101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.238101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koster G., Cacciuto A., Dogterom M. Force barriers for membrane tube formation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005;94:068101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.068101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gompper G., Kroll D.M. Driven transport of fluid vesicles through narrow pores. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys. Plasmas Fluids Relat. Interdiscip. Topics. 1995;52:4198–4208. doi: 10.1103/physreve.52.4198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Basu R., Munteanu E.L., Chang F. Role of turgor pressure in endocytosis in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2014;25:679–687. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-10-0618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun Y., Martin A.C., Drubin D.G. Endocytic internalization in budding yeast requires coordinated actin nucleation and myosin motor activity. Dev. Cell. 2006;11:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Molloy J.E., Burns J.E., White D.C. Movement and force produced by a single myosin head. Nature. 1995;378:209–212. doi: 10.1038/378209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mogilner A., Oster G. Force generation by actin polymerization II: the elastic ratchet and tethered filaments. Biophys. J. 2003;84:1591–1605. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74969-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blanchoin L., Amann K.J., Pollard T.D. Direct observation of dendritic actin filament networks nucleated by Arp2/3 complex and WASP/Scar proteins. Nature. 2000;404:1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/35010008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bar-Ziv R., Moses E. Instability and “pearling” states produced in tubular membranes by competition of curvature and tension. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994;73:1392–1395. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.73.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nelson P., Powers T., Seifert U. Dynamical theory of the pearling instability in cylindrical vesicles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995;74:3384–3387. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.3384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bar-Ziv R., Tlusty T., Bershadsky A. Pearling in cells: a clue to understanding cell shape. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:10140–10145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Evans E., Rawicz W. Entropy-driven tension and bending elasticity in condensed-fluid membranes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990;64:2094–2097. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.64.2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsafrir I., Sagi D., Stavans J. Pearling instabilities of membrane tubes with anchored polymers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001;86:1138–1141. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chadda R., Howes M.T., Mayor S. Cholesterol-sensitive Cdc42 activation regulates actin polymerization for endocytosis via the GEEC pathway. Traffic. 2007;8:702–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dannhauser P.N., Ungewickell E.J. Reconstitution of clathrin-coated bud and vesicle formation with minimal components. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:634–639. doi: 10.1038/ncb2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mashl R.J., Bruinsma R.F. Spontaneous-curvature theory of clathrin-coated membranes. Biophys. J. 1998;74:2862–2875. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77993-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun S.X., Wirtz D. Mechanics of enveloped virus entry into host cells. Biophys. J. 2006;90:L10–L12. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.074203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.