Abstract

Autophagy is a highly regulated pathway that selectively degrades cellular constituents such as protein aggregates and excessive or damaged organelles. This transport route is characterized by engulfment of the targeted cargo by autophagosomes. The formation of these double-membrane vesicles requires the covalent conjugation of the ubiquitin-like protein Atg8 to phosphatidylethanolamine (PE). However, the origin of PE and the regulation of lipid flux required for autophagy remain poorly understood. Using a genetic screen, we found that the temperature-sensitive growth and intracellular membrane organization defects of mcd4-174 and mcd4-P301L mutants are suppressed by deletion of essential autophagy genes such as ATG1 or ATG7. MCD4 encodes an ethanolamine phosphate transferase that uses PE as a precursor for an essential step in the synthesis of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor used to link a subset of plasma membrane proteins to lipid bilayers. Similar to the deletion of CHO2, a gene encoding the enzyme converting PE to phosphatidylcholine (PC), deletion of ATG7 was able to restore lipidation and plasma membrane localization of the GPI-anchored protein Gas1 and normal organization of intracellular membranes. Conversely, overexpression of Cho2 was lethal in mcd4-174 cells grown at restrictive temperature. Quantitative lipid analysis revealed that PE levels are substantially reduced in the mcd4-174 mutant but can be restored by deletion of ATG7 or CHO2. Taken together, these data suggest that autophagy competes for a common PE pool with major cellular PE-consuming pathways such as the GPI anchor and PC synthesis, highlighting the possible interplay between these pathways and the existence of signals that may coordinate PE flux.

Keywords: autophagy, Atg8, phospholipids, GPI anchor, Mcd4

LOCAL glycerophospholipid levels depend on several processes, including biosynthesis, remodeling, degradation, and interorganellar trafficking. Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) and phosphatidylcholine (PC) are key building blocks of membrane bilayers and account for up to 50% of phospholipids in eukaryotic cells. PE is typically synthesized from phosphatidylserine (PS) by phosphatidylserine decarboxylases (Psd1 and Psd2) and can be converted to PC through the addition of three methyl groups by the methyltransferases Cho2 and Opi3 (Mcgraw and Henry 1989). Cho2 is required for the first methylation reaction during PC biosynthesis, and Opi3 catalyzes the last two steps (Carman and Han 2011). PE also can be generated through the Kennedy (or salvage) pathway from diacylglycerol and ethanolamine by the sequential action of Eki1, Ect1, and Ept1 (Henry et al. 2012; McMaster and Bell 1994). In addition to serving as main constituents of membrane bilayers, PE is also used to covalently modify a subset of proteins, thereby regulating several cellular pathways, including glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchoring and autophagy. However, little is known about how eukaryotic cells coordinate PE homeostasis and distribution into these different pathways.

Autophagy targets subcellular organelles and macromolecular complexes for degradation in vacuoles/lysosomes. This highly conserved process ensures cellular homeostasis and plays crucial roles during nutrient starvation and cellular responses to stress conditions, including pathogen invasion. Autophagosomes are able to sequester portions of cytoplasm or specific cargo and rapidly deliver them into the lysosomes/vacuoles for degradation (Suzuki et al. 2002). Yeast cells also use the related cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting (Cvt) pathway to selectively deliver specific vacuolar enzymes such as aminopeptidase 1 (Ape1) and α-mannosidase (Ams1) (Harding et al. 1995; Hutchins and Klionsky 2001; Yuga et al. 2011).

Genetic analyses in yeast have identified over 36 mostly conserved components required for different steps of autophagy, named Atg1 to Atg36 (Suzuki et al. 2007; Motley et al. 2012). Autophagy activation triggers the formation of the Atg5-Atg12-Atg16 complex, which, in turn, catalyzes the covalent conjugation of the C-terminus of the ubiquitin-like protein Atg8 (LC3, GABARAP, and GABARAP-like proteins in mammals) to PE (Xin et al. 2001; He et al. 2003). This lipid anchor mediates association of Atg8 with autophagosomal membranes, where it forms a protein coat and binds specific cargo receptors (Behrends et al. 2010; Noda et al. 2010; Suzuki et al. 2010). The amount of Atg8-PE correlates with the size of autophagosomes, suggesting that expression and modification of Atg8 provides a rate-limiting step for flux through the autophagy pathway (Xie et al. 2008).

In addition to modifying Atg8, PE serves as a donor molecule at multiple steps in GPI anchor synthesis. These unique glycolipids are generated by the sequential addition of one N-acetylglucosamine and three mannose residues on a phosphatidylinositol (PI) molecule. This basic structure is further modified by deacetylation of the N-acetylglucosamine and addition of phosphoethanolamine (P-EtN) groups and in most cases additional mannoses. The terminal P-EtN residue is used to covalently link the C-terminus of specific proteins to the GPI anchor through a phosphodiester bond, resulting in protein association with membranes (Canivenc-Gansel et al. 1998). In yeast, the GPI biosynthetic pathway is essential for cell growth and survival and targets approximately 60 proteins mostly required for enzymatic functions in cell wall biosynthesis. The synthesis and conjugation of the GPI anchors to target proteins involves at least 19 proteins, named Gpi1 to Gpi19, that are localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). MCD4 is required to add a P-EtN group to one of the mannose residues composing the GPI anchor sugar core, and a reduction of its activity leads to accumulation of unanchored GPI proteins in the ER. Likewise, deletion of PIG-N, a mammalian homolog of MCD4, reduces surface expression of GPI-anchored proteins and loss of the enzyme activity that adds P-EtN groups to Man1 (Hong et al. 1999).

We are interested in the mechanisms that regulate autophagy and aim to identify them through the use of genetic screens. Surprisingly, we found that deletion of autophagy genes rescues the lethality of temperature-sensitive (ts) mcd4-174 cells, implying a functional link between autophagy and GPI anchor biosynthesis. Subsequent characterization of this genetic interaction revealed that this effect is caused by a limited PE pool that is used for multiple pathways, including PC and GPI anchor synthesis and autophagosome formation.

Materials and Methods

Growth conditions and strain construction

Yeast cells were grown in rich medium (YPD; 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) or synthetic dextrose medium (SD; 0.17% yeast nitrogen base, 0.5% ammonium sulfate, 2% glucose, amino acids as required). Nitrogen starvation was induced by growing cells to an optical density (OD600) of 0.5–0.8, washing them once in starvation medium (SD-N; 0.17% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 2% glucose), and resuspending them in SD-N for 4 hr. The genotype was as follows: RYY52 (MATα trp1, lys2, ura3, leu2, his3, suc2, psd1Δ-1::TRP1), S288C (his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0), unless otherwise noted. Haploid deletion strains were obtained after dissecting sporulated heterozygous diploid deletion strains purchased from Euroscarf (Frankfurt, Germany), and the kanamycin-resistant haploids were verified by PCR. The ts strains were obtained from the collection provided by the Boone Laboratory (University of Toronto, Canada). The mcd4Δ atg7Δ double mutant was constructed by homologous recombination of the corresponding kanMX deletion cassette into the homologous locus of the gene to be deleted in the heterozygous diploid. The double-deletion heterozygous diploid strain was sporulated and dissected, and the resulting spores were checked for viability and replica plated to determine genotype. All strains and plasmids used in this study can be found in File S1.

Screening procedure and validation of candidates

The kanamycin-resistant ts-strain collection (Li et al. 2011) was crossed against a bait haploid deletion strain of atg1Δ::NAT (can1::STE2pr-Sp_his5lyp1Δ his3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ met15Δ) or wild-type (WT) S288C. Haploid cells were selected with the procedure described previously (Tong et al. 2001). After the final selection step, haploid cells were pinned in duplicate and grown at permissive (22°), semipermissive (30°), and restrictive (37°) temperatures. Resulting colony size then was analyzed using the Goldeneye software developed by Dr. Serge Pelet. Candidates that were lethal at restrictive temperature in a WT background but that regained viability after deletion of ATG1 were classified as negative regulators of autophagy. Candidates that remained viable at semipermissive temperature in a WT background but became nonviable on deletion of ATG1 were defined as activators of autophagy. Promising candidates were manually recrossed by mating before selecting heterozygous diploid cells on YPD plates containing kanamycin and clonat, followed by sporulation on plates as described previously. Spores were manually dissected 7 days after sporulation, and double mutants were selected by replica plating. Serial dilutions of cells were spotted on YPD (1.5 μl of 1 × 107 to 1 × 103 cells/ml) and grown for 3 days at permissive (22°) or restrictive (37°) temperature. Colony size and number were compared visually.

Assay for YW3548 sensitivity

Plates containing YPD medium in 2% agar were spread with the indicated amounts of YW3548 (Sutterlin et al. 1997) in 200 μl of methanol. Tenfold serial dilutions (5-μl spots containing 101–105 cells) then were spotted onto the plates. Colony growth was determined visually after 5 days of incubation at 30°.

Ethanolamine growth assay

Yeast cells were grown at permissive temperature (22°) in SD (as described previously) to log phase and diluted in SD with or without the addition of 5 mM ethanolamine. Cells then were grown over a period of 30 hr at restrictive temperature (37°), and cell growth was determined periodically by OD600 density.

Western blot and Atg8-PE analysis

Cells were grown to log phase and lysed in 250 μM NaOH and 0.5% 2-mercaptoethanol, followed by trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation of total proteins. For Atg8-PE measurements, cells were grown at 37° to OD600 0.8 in SC medium and then resuspended in SD-N and incubated at 37° for 3 hr. TCA precipitates were washed with acetone and resuspended in sample buffer containing 6 M urea. Total protein extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose. Membranes were blocked with 5% milk and 1% bovine serum albumin and incubated with appropriate antibodies: rabbit polyclonal antiserum against Gas1 (1:25,000), mouse monoclonal antibody against GFP (1:1000; Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland), rabbit peptide antibody against Ape1 (1:1000), rabbit polyclonal antiserum against Atg8 (1:1000), mouse monoclonal antibody against Pgk1 (1:3000; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Immunofluorescence of Cwp2-VENUS

Cells were transformed with a plasmid p416-Cwp2-VENUS (Castillon et al. 2009). Transformed cells were grown overnight in SD-Ura at 22°. Cells were then diluted into SD without uracil and incubated for 4 hr at 37°. Then 5 μl of cells was spotted onto a microscope slide, and live cells were imaged using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 (Thornwood, NY). Localization of Cwp2-VENUS to the plasma membrane was analyzed visually in >100 cells/strain in three independent experiments.

Electron microscopic analysis of strains

Strains were grown overnight at 22° in YPD, diluted into YPD, and grown at 37° for 3 hr. Electron microscopic (EM) analysis was carried out as described previously (Griffith et al. 2008).

Lipid analysis

Cells were grown in rich medium until saturation, diluted to 0.2 OD/ml, and incubated at 22° or 37° for 6 hr. Lipids were quantified as described by Santos et al. (2014) (different fonts). Briefly, cells were resuspended in 1.5 ml of extraction solvent [ethanol, water, diethyl ether, pyridine, and 4.2 N ammonium hydroxide (15:15:5:1:0.018 v/v)]. A mixture of internal standards (7.5 nmol 17:0/14:1 PC, 7.5 nmol 17:0/14:1 PE, 6.0 nmol 17:0/14:1 PI, 4.0 nmol 17:0/14:1 PS, 1.2 nmol C17:0-ceramide, and 2.0 nmol C8-glucosylceramide) and 250 µl of glass beads was added, and the sample was vortexed vigorously (Multitube vortexer, Lab-tek International Ltd., Christchurch, New Zealand) at maximum speed for 5 min and incubated at 60° for 20 min. Cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 1800 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant was collected. The extraction was repeated once, and the supernatants were combined and dried under a stream of nitrogen or under vacuum in a Centrivap (Labconco Corporation, Kansas City, MO). The sample was divided into two equal aliquots. One-half was used for ceramide and sphingolipid analysis, where we performed an extra step to deacylate glycerophospholipids using monomethylamine reagent [methanol, water, n-butanol, methylamine solution (4:3:1:5 v/v)](Cheng et al. 2001) to reduce ion suppression owing to glycerophospholipids in sphingolipid detection. For desalting, both lipid extracts were resuspended in 300 µl of water-saturated butanol and sonicated for 5 min. Then 150 µl of LC-MS grade water was added, and samples were vortexed and centrifuged at 3200 × g for 10 min to induce phase separation. The upper phase was collected. Another 300 µl of water-saturated butanol was added to the lower phase, and the process was repeated twice. The combined upper phases were dried and kept at −80° until analysis. For glycerophospholipid and sphingolipid analysis by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS), lipid extracts were resuspended in 500 µl of chloroform:methanol (1:1 v/v) and diluted in chloroform:methanol:water (2:7:1 v/v/v) and chloroform:methanol (1:2 v/v) containing 5 mM ammonium acetate for positive and negative modes, respectively. A Triversa Nanomate (Advion, Ithaca, NY) was used to infuse samples with a gas pressure of 30 Psi and a spray voltage of 1.2 kV on a TSQ Vantage (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The mass spectrometer was operated with a spray voltage of 3.5 kV in positive mode and 3 kV in negative mode. The capillary temperature was set to 190°. Multiple-reaction monitoring mass spectrometry (MRM-MS) was used to identify and quantify lipid species as described previously (Guan et al. 2010). Data were converted and quantified relative to standard curves of internal standards, which had been spiked in prior to extraction. The values were normalized owing to variability between replicates. The average of WT triplicates was set to 1, and the mutant data are presented as fold change (mutant/WT). Values are averages ± SD of at least three independent samples. Details on lipid compounds and experimental results of this study are also available on the website lipidomes.org.

Analysis of Cho2 overexpression

pEGH-Gal1/10-Cho2 was obtained from the yeast GST fusion collection (Zhu et al. 2001). The plasmid was transformed into cells, and the resulting transformants were analyzed on plates by sequential dilution spotting onto solid medium containing 2% agar, SC without uracil, and 2% raffinose or 2% galactose. Plates were incubated for 3 days at 22° and 37°.

Results

Identification of novel autophagy regulators among the essential genes

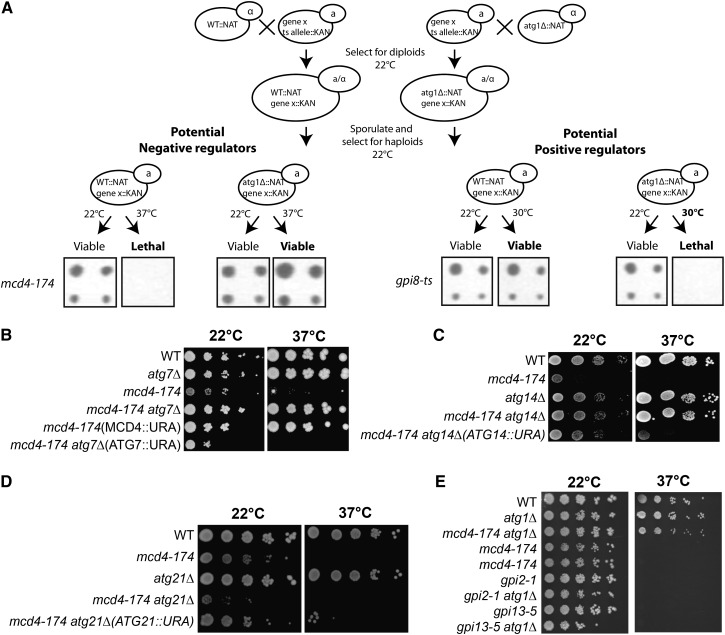

To identify novel regulators of autophagy or essential pathways influenced by autophagy, we screened a large collection of ts mutants in essential genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for those in which viability is restored by blocking all autophagic processes through deletion of ATG1 (Figure 1A). The underlying assumption of this approach was that repressors of autophagy might be essential because in their absence this pathway would be constitutively active. Moreover, this genetic screen is expected to identify essential cellular pathways that functionally interact with autophagy. Conversely, positive regulators of autophagy or cellular processes that require an intact autophagy process for viability were screened by isolating ts mutants that are nonviable at nonrestrictive temperature in the absence of ATG1 (Figure 1A). For both approaches, we deleted ATG1 by crossing the available ts collection (Li et al. 2011) with the atg1Δ bait strain (BY7092) and isolated haploid MATa cells after sporulation and appropriate selection. Synthetic-sick interactions between ts mutants and atg1Δ observed at 30° were confirmed by tetrad analysis, and the strength of the genetic interaction was categorized by measuring the colony size of the resulting double mutants (Supporting Information, Table S1A). Interestingly, this analysis identified genes that exhibit synthetic sickness with atg1Δ but not with deletions in other autophagy genes, suggesting that Atg1 may have non-autophagy-related functions that will be analyzed in detail elsewhere. The viable atg1Δ double mutants were shifted to the restrictive temperature (37°), and the growing colonies were scored after 3 days. Identified mutants were verified by spotting assays followed by manual dissection (Table S1B). Interestingly, one of the identified potential negative regulators of autophagy was MCD4 (Gaynor et al. 1999) because, in contrast to mcd4-174 strains, mcd4-174 atg1Δ double mutants were able to grow at 37° (Figure 1B). This suppression also was observed by deleting ATG7 (Figure 1B) or ATG14 (Figure 1C), and as expected, the effect was lost after complementation of the deletions with plasmids expressing WT Mcd4, Atg7, and Atg14, respectively. In contrast, deletion of ATG21, a gene required for the selective cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting (Cvt) pathway (Meiling-Wesse et al. 2004), was unable to rescue the lethality of mcd4-174 at the restrictive temperature (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

General autophagy mutants can rescue mcd4-174 lethality. (A) Schematic representation of screening the yeast ts collection for essential genes that are positively or negatively influenced by autophagy. The insets show an example candidate from each, including a member of the GPI-anchoring pathway, mcd4-174. (B–D) Dilution spotting of mcd4-174 crossed with various autophagy mutants. Deletion of genes required for general autophagy is able to rescue the lethality of mcd4-174 at restrictive temperature. This rescue phenotype was reverted when the WT gene was expressed from a plasmid. Deletion of genes required for specific autophagy pathways, e.g., Cvt (atg21), are unable to rescue lethality of mcd4-174 at restrictive temperature. (E) Dilution spotting of ts alleles of other members of the GPI-anchoring pathway functioning either upstream (Gpi2) or downstream (Gpi13) of Mcd4.

To examine whether the observed phenotype was a general feature of cells with perturbed Mcd4 function, we analyzed whether deletion of ATG7 was able to restore growth of mcd4Δ or cells harboring the mcd4-P301L allele (Storey et al. 2001). Interestingly, mcd4-P301L atg7Δ double mutants were able to grow at restrictive temperature (Figure S1A), implying that this genetic suppression is not limited to a single mcd4 allele. In contrast, tetrad analysis revealed that deletion of ATG7 was unable to rescue viability of mcd4Δ cells (Figure S1B). Likewise, atg7Δ cells were sensitive to the Mcd4 inhibitor YW3548 (Sutterlin et al. 1997; Hong et al. 1999), implying that loss of autophagy does not bypass the need for residual Mcd4 activity (Figure S1C). Taken together, these results suggest that blocking general autophagy function restores growth of cells with reduced but not abolished Mcd4 activity.

Mcd4 has been characterized previously as an essential enzyme for GPI biosynthesis, and mcd4-174 cells fail to add the GPI anchor to proteins at restrictive temperature (Zhu et al. 2006). To examine whether the observed phenotype was specific for mcd4-174 or for all mutants displaying GPI anchor biosynthesis defects, we crossed atg1Δ cells with ts alleles of GPI2 (gpi2-1) and GPI13 (gpi13-5), two genes functioning up- and downstream of Mcd4 in GPI anchor biosynthesis, respectively, and growth of the resulting double mutants was then analyzed at restrictive temperature. As shown in Figure 1E, deletion of ATG1 was unable to restore the growth of gpi2-1 or gpi13-5 cells, implying that the observed suppression is specific for mcd4-174.

The mcd4-174 mutant is defective for general autophagy, and deletion of autophagy rescues its GPI-anchoring deficiency

Cells defective for autophagy are sensitive to nutrient starvation. To test whether MCD4 may be involved in autophagy, we examined mcd4-174 cells for starvation sensitivity. We observed that mcd4-174 cells exhibit reduced viability on prolonged nutrient starvation (Figure 2A).

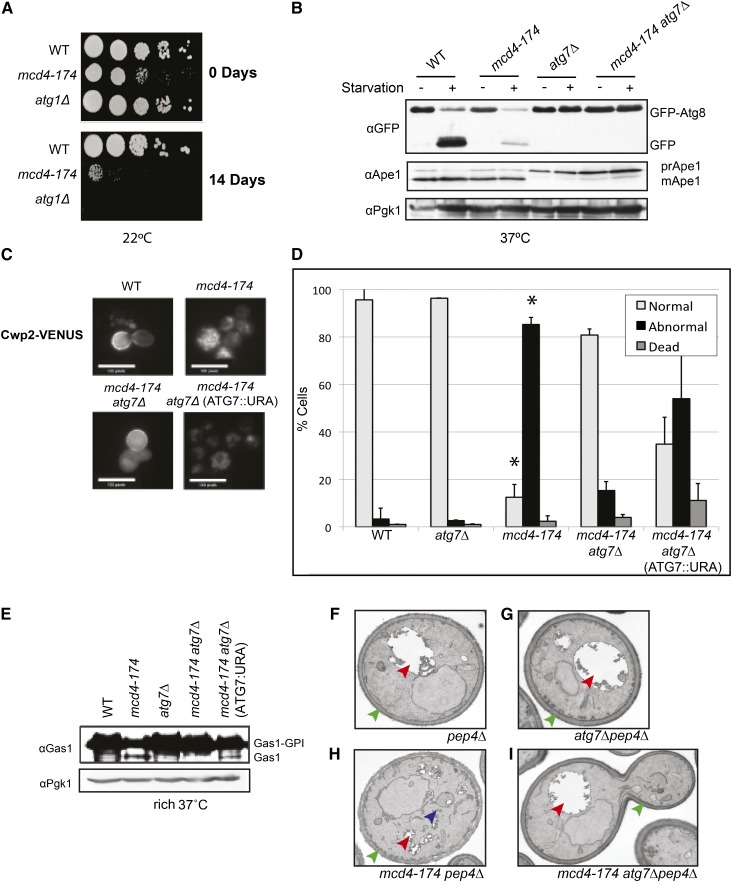

Figure 2.

Deletion of the autophagic pathway can rescue defects in GPI anchor synthesis in an mcd4-174 strain. (A) Dilution spotting of mcd4-174 cells grown at permissive temperature (22°) under normal nutrient conditions (0 days) or prolonged nutrient starvation (14 days). (B) Western blot analysis of yeast cell lysate derived from WT or mutant cells grown at restrictive temperature (37°, 4 hr) expressing GFP-Atg8. Detection of endogenous Ape1 maturation from its unprocessed precursor (preApe1) to its processed form (mApe1) is used as a readout for the Cvt pathway in rich medium and general autophagy in starvation conditions (see Materials and Methods). GFP-Atg8 cleavage is used to monitor general autophagy. Note that mcd4-174 cells are defective for general autophagy. Detection of endogenous Pgk1p was used as a loading control. (C) The localization of GPI-anchored protein Cwp2-VENUS was analyzed by microscopic analysis in WT and the indicated mutant strains shifted to 37° for 4 hr. Note that Cwp2-VENUS is trapped in the ER in mcd4-174 mutants, but cell wall localization is restored in mcd4-174 atg7∆ cells. (D) Graph of Cwp2-VENUS localization quantification from at least 200 cells with images acquired as in (C) expressed as a percentage of total cells (Normal = cell wall localization; Abnormal = ER localization). Data shown are average and SD of independent biological replicates (n = 3). *P < 0.05, t-test as compared with WT. Note that cell viability is not affected, demonstrating that reduced autophagy in mcd4-174 cells does not result from excess cell death. (E) Western blot detecting endogenous Gas1 in its GPI-anchored form (Gas1-GPI, higher-MW band) or non-GPI-anchored form (Gas1, lower-MW band) from WT and mutant cell lysates grown in rich medium at the nonpermissive temperature (37°). In mcd4-174 but not mcd4-174 atg7∆ cells, a lower-MW band accumulates corresponding to nonanchored Gas1. Detection of endogenous Pgk1 was used as a loading control. (F–I) Transmission EM images of mutant yeast cells grown at nonpermissive temperature (37°) showing various GPI-anchoring defects, which are rescued by deletion of the ATG7 gene required for autophagy (red arrow, vacuole; green arrow, cell wall; blue arrow, accumulation of abnormal membranes).

Next, we measured the flux through selective and bulk autophagy pathways in mcd4-174 cells shifted to restrictive temperature for 4 hr. Vacuolar maturation of the aminopeptidase Ape1 under nutrient-rich conditions was unaffected (Figure 2B), indicating that the selective Cvt pathway does not require Mcd4. Under autophagy-inducing conditions, however, the unprocessed Ape1 levels were slightly increased in the mcd4-174 mutant compared with the WT control, revealing a partial defect in general autophagy. To assess the progression of autophagy, cleavage of GFP-Atg8 was monitored under starvation conditions (Kim et al. 2001) and found to be significantly delayed in mcd4-174 cells. We could not observe a significant change in the levels of lipidated Atg8 in mcd4-174 mutants compared with WT controls (Figure S2), indicating that activation of the autophagy pathway is not affected. Together these data suggest that Mcd4 is not a negative regulator of autophagy but rather may promote general autophagy by a direct or indirect mechanism.

To explore a possible link between the function of Mcd4 in autophagy and its known role in GPI anchor biosynthesis, we tested by light microscopy whether the loss of autophagy improves GPI anchor conjugation to proteins and transport in mcd4-174 cells. Cell wall protein Cwp2, which undergoes GPI anchoring in the ER before being targeted to the cell wall, was used as a marker. As expected, Cwp2 tagged with the fluorescent VENUS protein localized predominantly to the cell wall of growing buds (scored as normal) but was mostly retained in the ER (scored as abnormal) in the mcd4-174 strain (Figure 2, C and D). Localization of this fluorescent chimera, however, was almost completely restored in the mcd4-174 atg7Δ double mutant but not in the mcd4-174 atg7Δ strain reexpressing ATG7 from a plasmid. GPI anchor linkage to proteins and transport also can be monitored by analyzing the major yeast GPI-anchored protein Gas1 via immunoblotting because the immature ER-resident Gas1 has a molecular weight of 105 kDa compared with 125 kDa for anchored plasma membrane–localized Gas1 (Conzelmann et al. 1988). In contrast to WT or atg7Δ strains, a faster-migrating unmodified Gas1 species was detectable in mcd4-174 cells that was absent in the mcd4-174 atg7Δ double mutant (Figure 2D). Together these results demonstrate that the in vivo function of Mcd4 in GPI anchor biosynthesis is enhanced in the absence of autophagy.

We next examined the morphology of mcd4-174 atg7Δ double mutants. In contrast to WT or atg7Δ cells, transmission electron microscopic analysis of the mcd4-174 mutant grown at the restrictive temperature revealed many cellular abnormalities, including the accumulation of abnormal membrane structures, fragmented vacuoles, and cell wall defects (Figure 2, F–I) (Gaynor et al. 1999). Strikingly, this phenotype was not observed with the mcd4-174 atg7Δ double mutant, suggesting that the cellular phenotypes associated with loss of Mcd4 function are largely suppressed in the absence of autophagy.

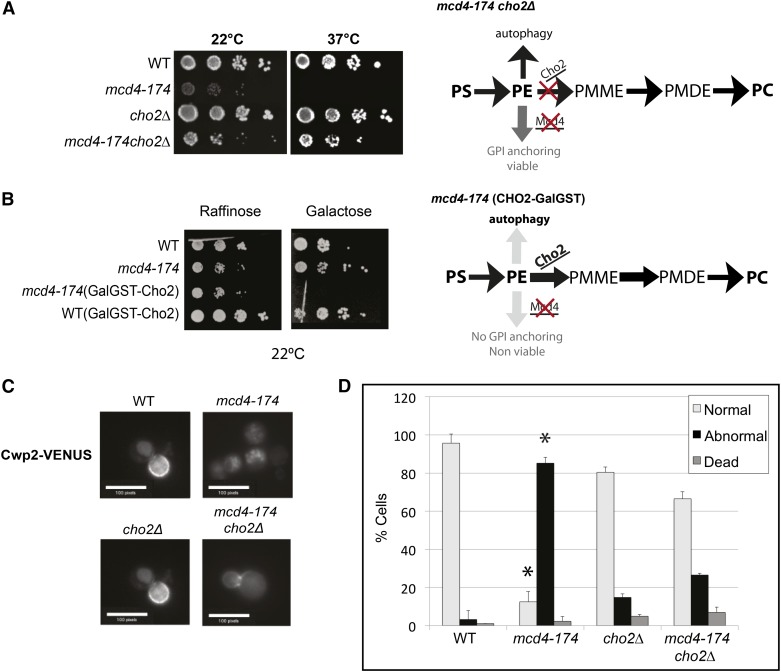

Growth of mcd4-174 cells is affected by altering PE levels in vivo by overexpression or deletion of Cho2

Because the GPI anchor biosynthesis and autophagy pathways both require PE as a substrate, we hypothesized that the phenotypes observed in the mcd4-174 strain could be caused by a reduction in the available PE pool. To test this hypothesis, we genetically altered the cellular PE levels by overexpression or deletion of the PE methyltransferase Cho2, which catalyzes the first step in the conversion of PE to PC (Figure 3, A and B). Indeed, similar to ATG1 or ATG7, deletion of CHO2 rescued the inviability of mcd4-174 cells (Figure 3A), and the failure to localize Cwp2-VENUS to the plasma membrane was restored in the mcd4-174 cho2Δ double mutants (Figure 3, C and D). Conversely, overexpression of Cho2 from the galactose-inducible GAL1,10 promoter was lethal in mcd4-174 but not WT cells grown at 22° on medium containing 2% galactose but not 2% raffinose (Figure 3B). These results support the notion that growth of mcd4-174 cells might be affected by PE levels because altering the flux of PE-to-PC conversion increases or decreases the viability of the mcd4-174 cells accordingly.

Figure 3.

Alterations to the phospholipid synthesis pathway can rescue or exacerbate defects in an mcd4-174 strain. (A) Dilution spotting of WT and mutant yeast cells grown at permissive (22°) and nonpermissive (37°) temperatures in rich medium. Deletion of CHO2, a component of the phospholipid synthesis pathway, can partially rescue lethality of mcd4-174 at restrictive temperature. In a cho2Δ mutant, PC formation through the de novo pathway is reduced, and the flux of PE is pushed toward GPI anchoring, causing a partial rescue. (B) Dilution spotting of WT and mutant yeast cells grown at permissive (22°) temperature in medium supplemented with either raffinose or galactose, in which Cho2 overexpression is galactose induced. On Cho2 overexpression (galactose), the flux of PE is pushed toward PC formation, further impairing the residual activity of mcd4-174 at permissive temperature (22°). (C) The localization of GPI-anchored protein Cwp2-VENUS was examined by microscopic analysis in WT and the indicated mutant strains as per Figure 2C. Localization of Cwp2-VENUS is partially restored in a mcd4-174 cho2Δ mutant. (D) Graph is quantitation of the images in (C) carried out as described in Figure 2D.

Loss of autophagy and addition of ethanolamine restores PE levels and proliferation of mcd4-174 cells grown at restrictive temperature

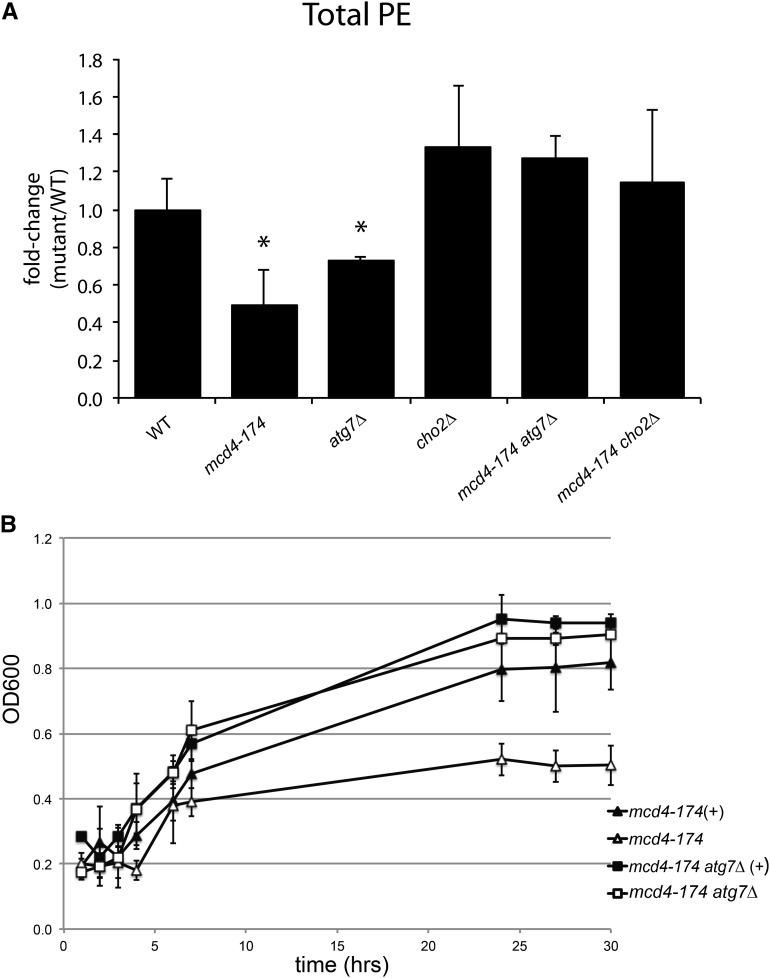

To directly test whether a defect in autophagy also could modulate the cellular PE levels, we compared the lipid composition of WT and different mutant cells at both permissive and restrictive temperatures. While the total amounts of sphingolipids, ceramides, and PI species in all strains were comparable with those in the WT control (Table S2), total PE levels were significantly reduced in mcd4-174 and surprisingly also in atg7Δ cells (Figure 4A). Importantly, however, the PE levels were restored in the mcd4-174 atg7Δ and mcd4-174 cho2Δ double mutants (Figure 4A), suggesting that increasing PE levels may improve growth of mcd4-174 cells.

Figure 4.

Loss of autophagy restores PE levels in mcd4-174 grown at restrictive temperature. (A) Lipid analysis shows that total PE levels after growth at 37° were reduced in mcd4-174 strains and increased in mcd4-174 atg7∆ and mcd4-174 cho2∆. The total amount of PE was calculated as the sum of all PE species. Data are average and SD of independent biological replicates (n = 3), shown in the “Summary” of Table S2. *P < 0.05, t-test as compared with WT. (B) Growth curves of mutant yeast strains measuring OD600 change over time. .Addition of 5 mM ethanolamine to the medium can partially rescue the growth of mcd4-174 cells at restrictive temperature. The growth of WT (not shown) or mcd4-174 atg7∆ cells was unaffected by the addition of ethanolamine. Data are average and SD of independent biological replicates (n = 3).

To test this possibility directly, growth of mcd4-174 cells was measured at restrictive temperature in liquid medium supplemented with ethanolamine, which induces PE synthesis through the Kennedy pathway (Birner et al. 2001). While WT and mcd4-174 atg7Δ double mutants were unaffected by the addition of ethanolamine, the doubling time of mcd4-174 cells was significantly increased when grown in the presence of ethanolamine (Figure 4B and data not shown). Together these results suggest that the growth defect of mcd4-174 cells is manifested, at least in part, from a limited availability of PE for GPI anchor biosynthesis. These results strongly suggest that autophagy inhibition suppresses the growth defect of mcd4-174 cells by increasing PE levels and thus imply that Mcd4 may play a direct or indirect role in PE metabolism.

To further test this hypothesis, we analyzed the genetic interaction of mcd4-174 strains with PSD2, a gene involved in the conversion of PS to PE in vacuolar membranes, and ECT1, a gene of the CDP-ethanolamine pathway. Interestingly, growth of mcd4-174 psd2Δ and mcd4-174 ect1Δ double mutants at semipermissive temperature (30°) was strongly reduced compared with the corresponding mcd4-174, psd2Δ, or ect1Δ single mutants (Figure S3, A and B). Moreover, PSD1 and PSD2 have been shown previously to be effective multicopy suppressors of fsr2-1 (a mutant allele of MCD4) double mutants grown at restrictive temperature (Toh-E and Oguchi 2002). Together these data indicate that the viability of mcd4-174 cells is affected by generally altering PE levels rather than a specific cellular PE pool.

Discussion

Using a genetic screen, we have identified essential genes that genetically interact with a functional autophagy pathway. Among others, we found that the viability of mcd4-174 and mcd4-P301L cells at restrictive temperature is restored by the deletion of components required for general autophagy. Interestingly, detailed characterization revealed that the amount of PE available for the ethanolamine phosphate transferase Mcd4 becomes limiting under autophagy conditions. Our results thus not only provide new insights into the function of Mcd4 but also help us to understand the flux and regulation of major cellular PE-consuming pathways.

Identification of genetic interacters with genes essential for viability

Systematic screening of the large S. cerevisiae collection comprising ts mutants of most essential genes (Li et al. 2011) identified a small subset of mutants that positively or negatively depends on a functional autophagy pathway (Table S1). Because autophagy is important for cellular homoeostasis and provides new building blocks by degrading excess or misfolded proteins in the vacuole, synthetic-lethal interactions may reveal components that are involved in quality control or biosynthesis pathways. For example, SSC1 encodes an ATPase of the Hsp70 chaperon family (Blamowska et al. 2010), whereas Nop2 is required for ribosome biogenesis (Hong et al. 1997). Conversely, rescue of growth at high temperature identifies deficiencies of essential processes in which autophagy is exacerbating the situation. While the ts mutants in mcd4-174 and hyp2-8 were rescued by deleting any essential component of the autophagy pathway, cmd1-3 and sec17-1 were suppressed by deleting ATG1 but not ATG7, suggesting that Atg1 may have unknown functions in addition to triggering autophagy (Papinski et al. 2014).

Cells with decreased Mcd4 activity exhibit reduced PE levels

We have discovered that cells with reduced Mcd4 activity also exhibit decreased levels of PE at 37°, and this defect is at least partially responsible for their slow-growth defect. Why PE levels are reduced in this mutant is less clear. Mcd4 catalyzes the first ethanolamine phosphate transferase reaction in the GPI synthesis pathway and uses PE as a precursor to synthesize the membrane anchor. The mutation causing ts growth of mcd4-174 cells is located within a motif that is conserved in phosphodiesterases and pyrophosphatases and changes glycine 227 to a glutamic acid residue. A simple explanation for the lower PE levels is that rather than transferring the ethanolamine phosphate from PE to the GPI precursor, the mutant enzyme simply hydrolyses the PE without efficiently completing the transfer. Previous studies have shown an increase in ethanolamine phosphate in a mcd4-174 mutant (Storey et al. 2001), providing a precedent for this hypothesis. Alternatively, WT Mcd4 also may be involved in regulating PE levels through a different mechanism. PS levels are lower in all mcd4-174 single and double mutants at restrictive temperature (Table S2) and may limit the amount of precursor available for PE synthesis. Mcd4 also might regulate the activity of the PC synthesis and/or degradation pathway. Finally, the failure to export GPI-anchored proteins may induce ER-phagy and thus cause vacuolar digestion of membranes and large-scale hydrolysis of PE. Irrespective of the underlying molecular explanation, it is clear that addition of exogenous ethanolamine or an increase in intracellular PE levels by reducing the flux of this lipid through autophagy or PC synthesis suppresses most, if not all, phenotypes observed with the mcd4-174 mutant. It is unlikely that Mcd4 plays a direct role in autophagy. The autophagy defects observed in the mcd4-174 mutant are probably caused indirectly by the reduction of one or more particular pools of PE or the massively proliferated and possibly disturbed Golgi and ER compartments.

Regulation of PE synthesis and flux in major PE-consuming pathways

Our data suggest that the GPI anchor biosynthesis competes with autophagy and PC biosynthesis for a common PE pool. Under nutrient-rich conditions, PE production in WT cells is mainly directed to the synthesis of GPI anchors and PC production. This flux may change under starvation conditions because a substantial amount of PE is required for autophagosome formation during autophagy and thus is diverted away from the GPI anchor biosynthesis pathway. PE levels are reduced in the mcd4-174 cells, which renders them sensitive to Cho2 overexpression or deletion of PSD2 or ECT1. Conversely, the viability of mcd4-174 but not mcd4Δ cells is rescued by deletion of CHO2 or essential autophagy genes. We thus speculate that under starvation conditions, the conversion from PE to PC may be temporally inhibited to increase the availability of PE for autophagy while maintaining a basal level of GPI anchor synthesis to strengthen the cell wall. The mechanism of this inhibition is unclear at present but may include regulation of the activity of Cho1 or Cho2 by post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation or allosteric binding of metabolites. Alternatively, direct binding to Atg8 could alter their enzymatic activity or localization, and indeed, a potential conserved LC3-interacting region (LIR) is present in Cho2. Clearly, further work is required to elucidate the mechanisms of how PE flux through the major PE-consuming pathways is regulated and balanced to cope with the changing cellular needs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Charlie Boone for the ts yeast library and Dennis Voelker for the mcd4-P301L strain. We are grateful to Ingrid Stoffel-Studer, Janny Tilma, and Isabelle Riezman for technical support, Fabrice David for help with analysis of the mass spectrometry data, Serge Pelet for the Goldeneye software, and Alicia Smith for critical reading of the manuscript. M.P. is supported by the European Research Council (ERC), the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), and ETH Zürich; F.R. by the ALW Open Program (821.02.017 and 822.02.014), the DFG-NWO cooperation (DN82-303), and ZonMW-VIDI (917.76.329) and ZonMW-VICI (016.130.606) grants; and H.R. by SystemsX.ch (LipidX.ch, evaluated by the SNSF) and the SNSF.

Footnotes

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.114.169797/-/DC1

Communicating editor: D. J. Lew

Literature Cited

- Behrends C., Sowa M. E., Gygi S. P., Harper J. W., 2010. Network organization of the human autophagy system. Nature 466: 68–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birner R., Burgermeister M., Schneiter R., Daum G., 2001. Roles of phosphatidylethanolamine and of its several biosynthetic pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 12: 997–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blamowska M., Sichting M., Mapa K., Mokranjac D., Neupert W., et al. , 2010. ATPase domain and interdomain linker play a key role in aggregation of mitochondrial Hsp70 chaperone Ssc1. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 4423–4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canivenc-Gansel E., Imhof I., Reggiori F., Burda P., Conzelmann A., et al. , 1998. GPI anchor biosynthesis in yeast: phosphoethanolamine is attached to the α1,4-linked mannose of the complete precursor glycophospholipid. Glycobiology 8: 761–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman G. M., Han G. S., 2011. Regulation of phospholipid synthesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 80: 859–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillon G. A., Watanabe R., Taylor M., Schwabe T. M., Riezman H., 2009. Concentration of GPI-anchored proteins upon ER exit in yeast. Traffic 10: 186–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J., Park T. S., Fischl A. S., Ye X. S., 2001. Cell cycle progression and cell polarity require sphingolipid biosynthesis in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 6198–6209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conzelmann A., Riezman H., Desponds C., Bron C., 1988. A major 125-kd membrane glycoprotein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is attached to the lipid bilayer through an inositol-containing phospholipid. EMBO J. 7: 2233–2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor E. C., Mondesert G., Grimme S. J., Reed S. I., Orlean P., et al. , 1999. MCD4 encodes a conserved endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein essential for glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor synthesis in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 10: 627–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith J., Mari M., De Maziere A., Reggiori F., 2008. A cryosectioning procedure for the ultrastructural analysis and the immunogold labelling of yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Traffic 9: 1060–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan X. L., Riezman I., Wenk M. R., Riezman H., 2010. Yeast lipid analysis and quantification by mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol. 470: 369–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding T. M., Morano K. A., Scott S. V., Klionsky D. J., 1995. Isolation and characterization of yeast mutants in the cytoplasm to vacuole protein targeting pathway. J. Cell Biol. 131: 591–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H., Dang Y., Dai F., Guo Z., Wu J., et al. , 2003. Post-translational modifications of three members of the human MAP1LC3 family and detection of a novel type of modification for MAP1LC3B. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 29278–29287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry S. A., Kohlwein S. D., Carman G. M., 2012. Metabolism and regulation of glycerolipids in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 190: 317–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong B., Brockenbrough J. S., Wu P., Aris J. P., 1997. Nop2p is required for pre-rRNA processing and 60S ribosome subunit synthesis in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17: 378–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y., Maeda Y., Watanabe R., Ohishi K., Mishkind M., et al. , 1999. Pig-n, a mammalian homologue of yeast Mcd4p, is involved in transferring phosphoethanolamine to the first mannose of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 35099–35106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins M. U., Klionsky D. J., 2001. Vacuolar localization of oligomeric α-mannosidase requires the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting and autophagy pathway components in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 20491–20498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Huang W. P., Klionsky D. J., 2001. Membrane recruitment of Aut7p in the autophagy and cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathways requires Aut1p, Aut2p, and the autophagy conjugation complex. J. Cell Biol. 152: 51–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Vizeacoumar F. J., Bahr S., Li J., Warringer J., et al. , 2011. Systematic exploration of essential yeast gene function with temperature-sensitive mutants. Nat. Biotechnol. 29: 361–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw P., Henry S. A., 1989. Mutations in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae opi3 gene: effects on phospholipid methylation, growth and cross-pathway regulation of inositol synthesis. Genetics 122: 317–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMaster C. R., Bell R. M., 1994. Phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis via the CDP-choline pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: multiple mechanisms of regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 14776–14783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiling-Wesse K., Barth H., Voss C., Eskelinen E. L., Epple U. D., et al. , 2004. Atg21 is required for effective recruitment of Atg8 to the preautophagosomal structure during the Cvt pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 37741–37750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motley A. M., Nuttall J. M., Hettema E. H., 2012. Atg36: the Saccharomyces cerevisiae receptor for pexophagy. Autophagy 8: 1680–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda N. N., Ohsumi Y., Inagaki F., 2010. Atg8-family interacting motif crucial for selective autophagy. FEBS Lett. 584: 1379–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papinski D., Schuschnig M., Reiter W., Wilhelm L., Barnes C. A., et al. , 2014. Early steps in autophagy depend on direct phosphorylation of Atg9 by the Atg1 kinase. Mol. Cell 53: 471–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos A., Riezman I., Aguilera-Romero A., David F., Piccolis M., et al. , 2014. Systematic lipidomic analysis of yeast protein kinase and phosphatase mutants reveals novel insights into regulation of lipid homeostasis. Mol. Biol. Cell. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey M. K., Wu W. I., Voelker D. R., 2001. A genetic screen for ethanolamine auxotrophs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae identifies a novel mutation in Mcd4p, a protein implicated in glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor synthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1532: 234–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutterlin C., Horvath A., Gerold P., Schwarz R. T., Wang Y., et al. , 1997. Identification of a species-specific inhibitor of glycosylphosphatidylinositol synthesis. EMBO J. 16: 6374–6383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K., Kamada Y., Ohsumi Y., 2002. Studies of cargo delivery to the vacuole mediated by autophagosomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Dev. Cell 3: 815–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K., Kondo C., Morimoto M., Ohsumi Y., 2010. Selective transport of alpha-mannosidase by autophagic pathways: identification of a novel receptor, Atg34p. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 30019–30025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K., Kubota Y., Sekito T., Ohsumi Y., 2007. Hierarchy of Atg proteins in pre-autophagosomal structure organization. Genes to Cells 12: 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh-e A., Oguchi T., 2002. Genetic characterization of genes encoding enzymes catalyzing addition of phospho-ethanolamine to the glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Genet. Syst. 77: 309–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A. H., Evangelista M., Parsons A. B., Xu H., Bader G. D., et al. , 2001. Systematic genetic analysis with ordered arrays of yeast deletion mutants. Science 294: 2364–2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z., Nair U., Klionsky D. J., 2008. Atg8 controls phagophore expansion during autophagosome formation. Mol. Biol. Cell 19: 3290–3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin Y., Yu L., Chen Z., Zheng L., Fu Q., et al. , 2001. Cloning, expression patterns, and chromosome localization of three human and two mouse homologues of GABA(A) receptor-associated protein. Genomics 74: 408–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuga M., Gomi K., Klionsky D. J., Shintani T., 2011. Aspartyl aminopeptidase is imported from the cytoplasm to the vacuole by selective autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 286: 13704–13713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H., Bilgin M., Bangham R., Hall D., Casamayor A., et al. , 2001. Global analysis of protein activities using proteome chips. Science 293: 2101–2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Vionnet C., Conzelmann A., 2006. Ethanolaminephosphate side chain added to glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor by mcd4p is required for ceramide remodeling and forward transport of GPI proteins from endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 19830–19839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]