Abstract

Effective molecular target drugs that improve therapeutic efficacy with fewer adverse effects for esophageal cancer are highly anticipated. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors have been proposed as low-toxicity agents to treat double strand break (DSB)-repair defective tumors. Several findings imply the potential relevance of DSB repair defects in the tumorigenesis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). We evaluated the effect of a PARP Inhibitor (AZD2281) on the TE-series ESCC cell lines. Of these eight cell lines, the clonogenic survival of one (TE-6) was reduced by AZD2281 to the level of DSB repair-defective Capan-1 and HCC1937 cells. AZD2281-induced DNA damage was implied by increases in γ-H2AX and cell cycle arrest at G2/M phase. The impairment of DSB repair in TE-6 cells was suggested by a sustained increase in γ-H2AX levels and the tail moment calculated from a neutral comet assay after X-ray irradiation. Because the formation of nuclear DSB repair protein foci was impaired in TE-6 cells, whole-exome sequencing of these cells was performed to explore the gene mutations that might be responsible. A novel mutation in RNF8, an E3 ligase targeting γ-H2AX was identified. Consistent with this, polyubiquitination of γ-H2AX after irradiation was impaired in TE-6 cells. Thus, AZD2281 induced growth retardation of the DSB repair-impaired TE-6 cells. Interestingly, a strong correlation between basal expression levels of γ-H2AX and sensitivity to AZD2281was observed in the TE-series cells (R2 = 0.5345). Because the assessment of basal DSB status could serve as a biomarker for selecting PARP inhibitor-tractable tumors, further investigation is warranted.

Keywords: DNA repair, esophageal cancer, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, RNF8, γ-H2AX

Esophageal carcinoma is the sixth most common cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide and is associated with a poor prognosis.(1) Surgical therapies of resectable esophageal cancer exhibit a 5-year survival rate ranging from 20% to 27%.(2–4) Less invasive therapies that preserve the esophagus have also been introduced. Endoscopic therapies, such as endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), have been adopted for early esophageal cancer and have achieved favorable outcomes, but postoperative esophageal stricture frequently occurs after these treatments. Furthermore, intensive follow-up is necessary to manage new heterochronous lesions.(5–7) Chemoradiotherapy (CRT), which combines radiation, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and cisplatin (CDDP), is a promising therapeutic alternative to esophagectomy with a survival rate equivalent to that of surgical therapies.(8,9) However, the acute and late adverse effects of chemoradiotherapy, including pancytopenia and pneumonitis, still require consideration. There is a demand for effective molecular target drugs for esophageal cancer that combine an improved therapeutic efficacy with fewer adverse effects.

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors induce the accumulation of DNA single-strand breaks (SSB), which cause the formation of DNA double-strand breaks (DSB) after the stalling and collapse of progressing DNA replication folks.(10) Though DSBs are repaired by the error-free homologous recombination repair (HRR) pathway in non-tumor cells, they remain unrepaired and induce lethality in HRR-defective tumor cells.(11,12) Based on this mechanism, PARP inhibitors have been proposed as low toxicity agents for HRR-defective tumors. BRCA1 and BRCA2 are key components of the HRR machinery, and the abnormality of these genes is known to cause sporadic and hereditary breast and ovarian cancers.(13) Consistent with this, PARP inhibitors have been developed for breast and ovarian cancers. In addition, an increasing number of biomarker candidates that predict the sensitivity of a tumor to PARP inhibitors have been reported.(14–18)

Esophageal carcinoma is histologically classified into squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and adenocarcinoma; the former is common in East Asia. Although the direct relevance has not been well investigated, several findings suggest that a defect in the HRR pathway contributes to the tumorigenesis of ESCC. The risk of esophageal and head and neck squamous carcinoma is increased among Fanconi anemia (FA) patients whose HRR pathway was disturbed due to FA-predisposing gene alterations.(19,20) In addition, recently reported whole-exome sequencing data from 74 head and neck SCCs revealed that more than half of SCC cases harbored mutations in genes involved in DNA repair.(21) Therefore, we assume that some fraction of ESCCs harbor DSB repair defects and might be favorable targets of PARP inhibitors. The aim of this study was to examine the efficacy of a potent PARP-1 inhibitor in a series of ESCC cell lines established from Japanese patients.

Materials and Methods

Complete materials and methods were described in the supplementary information (Data S1).

Purchased materials

A PARP inhibitor, AZD2281 (Olaparib) and BSI-201 (Iniparib) were purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA). The TE-1, TE-4, TE-6, TE-8, TE-9, TE-10, TE-11 and TE-14 cell lines were purchased from the Riken BioResource Center (Tsukuba, Japan). The Capan-1, HCC1937, MDA-MB-436 and MCF-7 cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA).

Clonogenic assays

A total of 500–2000 cells were cultured with AZD2281- or vehicle-containing media. After 10–16 days, cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet. Colonies consisting of more than 64 cells were subsequently counted.

Immunoblotting analysis

The treated cell lysates were separated by 15% SDS-PAGE and the blot was hybridized with the phospho-Histone H2A.X (Ser139) (20E3) rabbit monoclonal antibody (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) and then with a HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:50000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). Densitometric analysis was performed with Image-J software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Immunofluorescence analysis

To evaluate the formation of DSBs, cells grown on 96-well plates were treated with an anti-γ-H2AX rabbit monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) followed by a goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) DyLight 549-conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). γ-H2AX was observed under an ArrayScan HCS System (Thermo Scientific). To evaluate the formation of 53BP1 and RAD51 nuclear foci, cells grown on μ-Dish35 mm,low (ibidi) were treated with an anti-53BP1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) or an anti-RAD51 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) followed by an Alexa Flour 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). These foci were observed under a BIOREVO BZ-9000 microscope (Keyence, Osaka, Japan).

Neutral comet assays

Neutral comet assays were performed using the CometAssay kit (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell cycle analysis

The cells were fixed with 70% ethanol and stained with propidium iodide. The DNA content of the cells was evaluated using a FACS CantoII flow cytometer and FACS Diva software (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Whole-exome sequencing

Targeted enrichment was performed using the SureSelect Human All Exon 50 Mb Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and sequenced using Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Individual experiments were performed at least in triplicate. The statistical significance of observed differences was analyzed using Student's t-test. One asterisk (*) indicates a P-value smaller than 0.05. Two asterisks (**) indicate a P-value smaller than 0.01.

Results

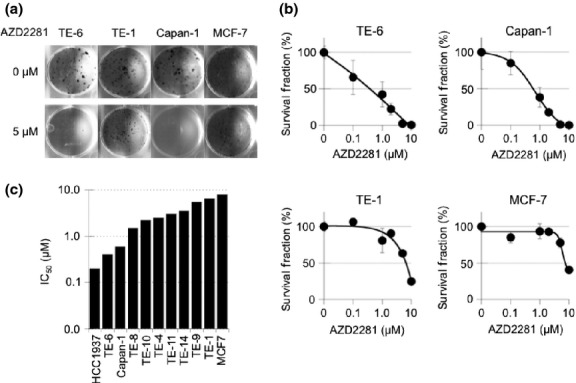

Sensitivity of TE series cell lines to AZD2281

We tested the sensitivity of the TE series of ESCC cell lines to AZD2281 using clonogenic assays. All of the cell lines were cultured with various concentrations of AZD2281 for at least seven doubling times (10–16 days), and the number of colonies with more than 64 cells was counted. The concentrations of AZD2281 that caused a 50% reduction in clonogenic survival (IC50) in the TE-6, TE-8, TE-10, TE-4, TE-11, TE-14, TE-9, and TE-1 cells were 0.4, 1.5, 2.2, 2.5, 3.0, 3.5, 5.5 and 6.5 μM, respectively (Figs 1a–c, S1). The IC50 values for HCC1937 and Capan-1 cells, which have deletions or mutations in the BRCA genes and are reported to be sensitive to PARP inhibitors,(22,23) were 0.2 and 0.6 μM, respectively. The IC50 values for MCF7 cells, which have wild-type BRCA genes and are known to be resistant to PARP inhibitors, was 8.0 μM. We further tested another PARP inhibitor, BSI-201. The IC50 values for TE-6 and TE-1 cells were 9.6 and 22.0 μM, respectively (Fig. S2). Because AZD2281 and BSI-201 suppressed the growth of the TE-6 cells as efficiently as it suppressed the growth of the BRCA-deficient, PARP-inhibitor-sensitive cell lines and failed to suppress the growth of the TE-1 cells; we designated TE-6 as a PARP inhibitor-sensitive ESCC cell line and TE-1 as a PARP inhibitor-resistant cell line. We selected these cells for further analyses.

Fig. 1.

Sensitivity of TE-series cell lines to a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, AZD2281. (a) TE-1, TE-6, Capan-1 (BRCA2-deficient) and MCF7 (wild-type BRCA) cells were treated with or without AZD2281 at the indicated concentrations for at least seven doubling times. Cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet and the number of colonies was counted. (b) Sensitivity to AZD2281 was evaluated by clonogenic assay. Colonies consisting of more than 64 cells were counted and the survival fraction was estimated. Three independent experiments were carried out. The data represent the average and standard deviations. (c) IC50 (μM) value of AZD2281 in eight TE series, MCF7, HCC1937 and Capan-1 cells measured by the clonogenic assays.

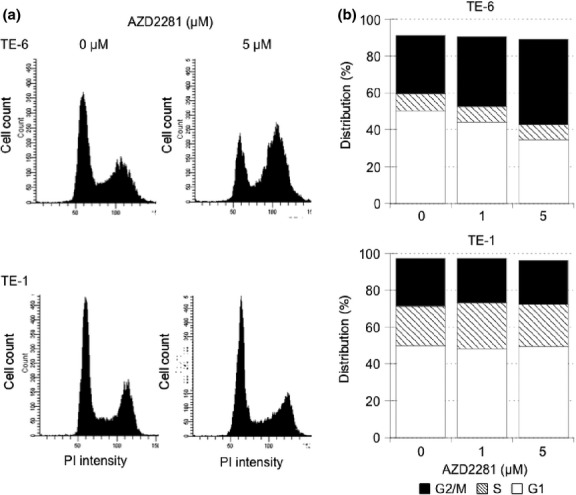

AZD2281-induced G2/M arrest in TE-6 cells

To further study the mechanism of growth retardation of TE-6 cells by AZD2281, the status of the cell cycle in these cells was assessed by analyzing the DNA ploidy pattern (Figs 2a,b, S3). Treatment with 1 and 5 μM of AZD2281 for 12 h increased the population with 4n DNA content from 36.7% to 40.7% and 40.6%, respectively. Treatment for 24 h further increased the population with 4n DNA content from 31.6% to 37.9% and 46.3%, respectively. This suggested an increase in the G2/M or M arrested population after AZD2281 treatment. On the other hand, no significant increase of tetraploid cells was observed in the TE-1 cells.

Fig. 2.

AZD2281-induced G2/M arrest in TE-6 cells. (a) TE-6 and TE-1 cells were cultured with or without AZD2281 for 24 h. DNA ploidy was assessed by propidium iodide (PI) staining and flow cytometry. (b) The proportion of estimated cell-cycle phases in TE-6 and TE-1 cells treated with or without AZD2281. The data represent the average of three independent experiments.

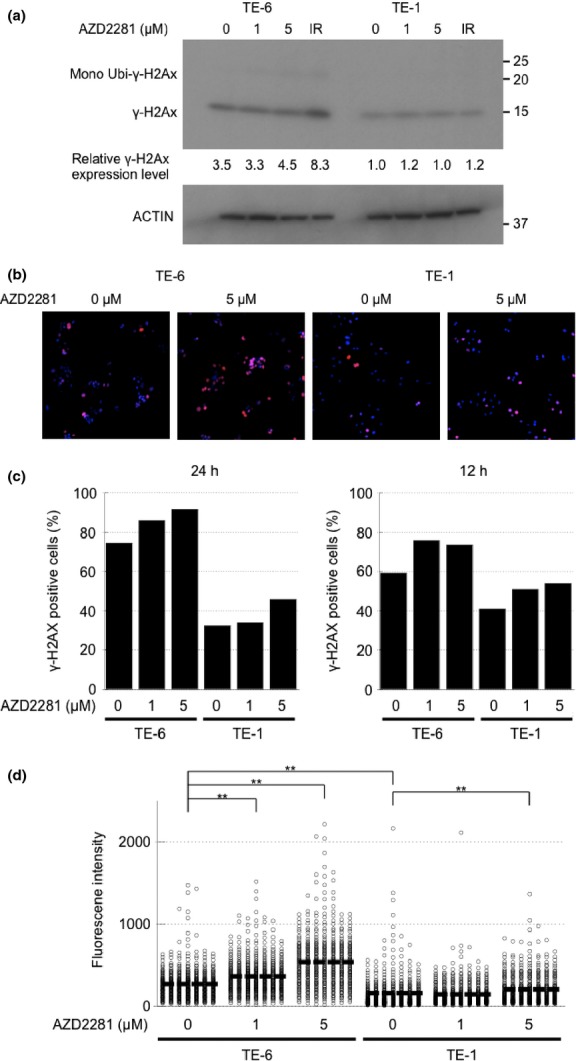

Increase of DSBs in TE-6 cells treated with AZD2281

To determine whether DSBs are formed after treatment with AZD2281 for 24 h, we assessed the amount of γ-H2AX as a marker of DSBs. Western blotting revealed that the level of γ-H2AX staining in TE-6 cells increased in a dose-dependent manner. However, no such increase was observed in TE-1 cells (Fig. 3a). The same trend was observed by immunofluorescence. Both the percentage of γ-H2AX positive cells determined by visual inspection and the average fluorescence intensity of γ-H2AX staining per cell increased significantly in a dose-dependent manner in TE-6 cells, but not in TE-1 cells, suggesting that AZD2281 induced an accumulation of DNA damage in TE-6 cells (Fig. 3b–d).

Fig. 3.

Increase in double strand breaks (DSBs) in TE-6 cells treated with AZD2281. (a) TE-6 and TE-1 cells were treated with AZD2281 for 24 h and with 5 Gy X-ray irradiation, and γ-H2AX was assessed using Western blotting. The anti-γ-H2AX antibody detected both unubiquitinated (15 kD) and mono-ubiquitinated (23.6 kD) γ-H2AX. (b) TE-6 and TE-1 cells were treated with AZD2281 for 24 h and γ-H2AX was assessed by immunofluorescence. DAPI (blue) and γ-H2AX (red) images were superimposed. (c) Number of the γ-H2AX-positive TE-6 and TE-1 cells treated with or without AZD2281 at the indicated concentrations for 24 h. (d) Scatter diagrams show the fluorescence intensity of individual TE-6 and TE-1 cells treated with or without AZD2281 at the indicated concentrations for 24 h. The lines shown indicated the averages of the data plotted. The data were obtained from at least 500 cells for each condition. **P < 0.01 (Student's t-test).

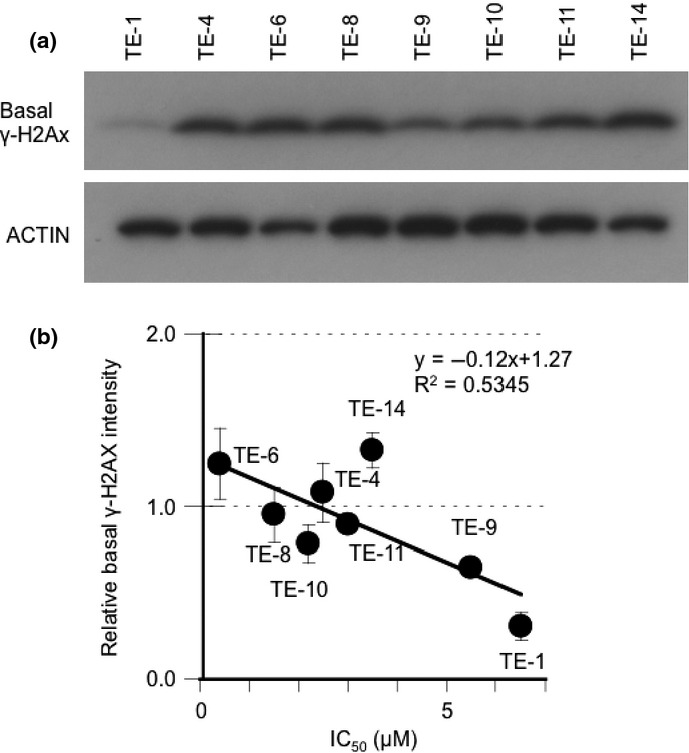

A strong correlation between base-level γ-H2AX and sensitivity to AZD2281 of TE cells

The Western blotting and immunofluorescence data also suggested that the baseline γ-H2AX level was higher in the AZD2281-sensitive TE-6 cells than in the resistant TE-1 cells (Fig. 3a). Because the increased amount of γ-H2AX may suggest the accumulation of DSBs, we evaluated the correlation between the basal expression levels of γ-H2AX and sensitivity to AZD2281 among the eight TE cell lines. A significant correlation between the basal levels of γ-H2AX and the IC50 of AZD2281 was observed (R2 = 0.5345) (Fig. 4a,b).

Fig. 4.

A strong correlation between base-level γ-H2AX and sensitivity to AZD2281 of TE cells. (a) Eight non-treated TE-series cell lines were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies against γ-H2AX and actin. (b) The correlation between basal γ-H2AX expression levels and IC50 of AZD2281. The average intensity of γ-H2AX was standardized with actin. The data represent the averages and standard deviations of three independent experiments.

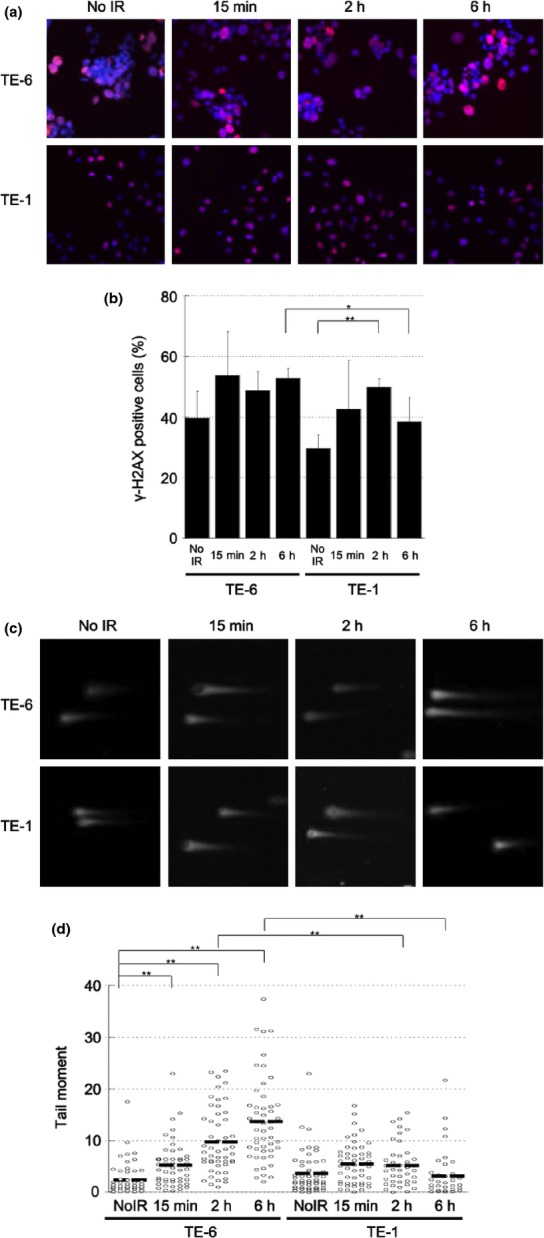

Sustained X-ray irradiation-induced DSBs in TE-6 cells

To assess whether the impairment of DSB repair is relevant to the sensitivity of TE-series cells to AZD2281, we evaluated X-ray irradiation-induced DNA DSBs in these cells. First, the amount of γ-H2AX was assessed by immunfluorescence. As mentioned above, the γ-H2AX level of TE-6 cells was high at baseline and increased 15 min after irradiation and sustained for 6 h. In TE-1 cells, increase of γ-H2AX level was observed 2 h after irradiation, but declined after 6 h (Fig. 5a,b). Next, a neutral comet assay was performed to assess DNA damage. This assay detects a wide range of DNA lesions, including DSBs; the tail moment parameter is used as an index of DNA damage. We found a sustained increase in the tail moment of TE-6 cells (irradiation [–]; 2.43 ± 3.19, 15 min; 5.27 ± 4.35 2 h; 9.78 ± 6.27, 6 h; 13.71 ± 8.20), while in TE-1 cells, the tail moment transiently increased at 2 h after 5 Gy X-ray irradiation and then returned to the basal level at 6 h (irradiation [–]; 3.69 ± 4.14, 15 min; 5.56 ± 3.97 2 h; 5.20 ± 4.22, 6 h; 3.20 ± 4.71) (Fig. 5c,d, Table 1). These results suggested that the X-ray irradiation-induced DNA damage was properly repaired in the TE-1 cells but was sustained in the TE-6 cells.

Fig. 5.

Sustained X-ray irradiation-induced double strand breaks (DSBs) in TE-6 cells. (a) TE-6 and TE-1 cells were irradiated with 2 Gy X-ray. Cells were stained with anti-γ-H2AX antibody 15 min, 2 and 6 h after irradiation. (b) Percentages of γ-H2AX-positive cells. The data represent the average and standard deviations of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (Student's t-test). (c) Representative neutral comet assay results of TE-6 and TE-1 cells treated with or without 5 Gy of X-ray irradiation. (d) Scatter diagrams show the tail moment of individual TE-6 and TE-1 cells treated with or without 5 Gy of X-ray irradiation. The lines shown indicate the averages of the data plotted. The data were obtained from at least 100 cells for each condition. *P < 0.01 (Student's t-test).

Table 1.

Tail moment of the X-ray-irradiated TE-6 and TE-1 cells

| Time after irradiation |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h | 15 min | 2 h | 6 h | |

| TE-6 | 2.43 ± 3.19 | 5.27 ± 4.35 | 9.78 ± 6.27 | 13.7 ± 8.20 |

| TE-1 | 3.69 ± 4.14 | 5.56 ± 3.97 | 5.20 ± 4.22 | 3.20 ± 4.71 |

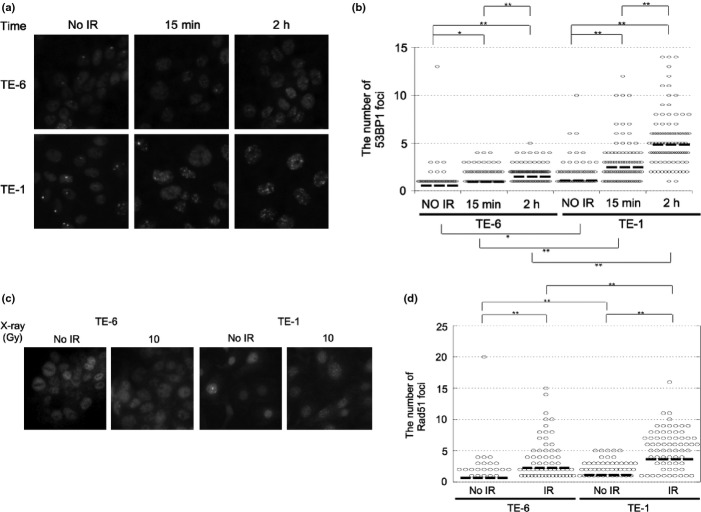

Impairment of DSB repair protein nuclear foci formation in X-ray irradiated TE-6 cells

Because the TE-6 cells were found to be defective in DSB repair, we assessed the amount of BRCA1/2 expression in TE-series cells by Western blotting (Fig. S4a,b). However, no significant difference in the expression of BRCA1/2 in TE-6 and TE-1 cells was observed. To confirm the impairment of DNA repair machinery of TE-6 cells, we evaluated the nuclear focus formation of 53BP1, which is recruited to the γ-H2AX sites at an early stage in DSB repair, and RAD51, which is recruited at a late stage in DSB repair.(24–26) The baseline expression levels of 53BP1 and RAD51 were higher in the TE-6 cells (Fig. S5). However, increase of the number of 53BP1 nuclear foci per cell was much less in the TE-6 cells (irradiation [–]; 0.55 ± 1.44, 15 min; 0.94 ± 1.12 2 h; 1.48 ± 1.20), whereas 53BP1 foci were increased in the TE-1 cells (irradiation [–]; 1.09 ± 1.58, 15 min; 2.48 ± 2.44 2 h; 4.86 ± 3.23) (Fig. 6a,b, Table 2). Similarly, 6 h after 10 Gy X-ray irradiation, the number of RAD51 foci per cell was significantly increased in the TE-1 cells (irradiation [–]; 1.11 ± 1.50, 6 h; 3.65 ± 3.59), whereas the increase in RAD51 foci was not significant in the TE-6 cells (irradiation [–]; 0.67 ± 2.20, 2 h; 2.25 ± 3.20) (Fig. 6c,d, Table 2). These results suggested that the interaction between γ-H2AX and 53BP1 and the subsequent recruitment of RAD51 were impaired in TE-6 cells.

Fig. 6.

Impairment of 53BP1 and RAD51 nuclear focus formation in X-ray irradiated TE-6 cells. (a) TE-6 and TE-1 cells were irradiated with 2 Gy of X-rays and fixed 15 min and 2 h after irradiation. The formation of 53BP1 nuclear foci was evaluated by immunofluorescence. (b) Scatter diagrams showing the number of 53BP1 foci in individual cells. The lines shown indicate the mean of the data plotted. The data were obtained from at least 100 cells for each condition. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (Student's t-test). (c) TE-6 and TE-1 cells were irradiated with 10 Gy of X-rays and fixed 6 h after irradiation. The formation of RAD51 nuclear foci was evaluated by immunofluorescence. (d) Scatter diagrams showing the number of RAD51 foci in individual cells. The lines shown indicate the mean of the data plotted. The data were obtained from at least 100 cells for each condition. **P < 0.01 (Student's t-test).

Table 2.

The number of nuclear foci of the DNA repair proteins

| X-Ray (Gy) | 53BP1 |

Rad51 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2 | 0 | 10 | ||

| Time | – | 15 min | 2 h | – | 2 h |

| TE-6 | 0.55 ± 1.44 | 0.94 ± 1.12 | 1.48 ± 1.20 | 0.67 ± 2.20 | 2.25 ± 3.20 |

| TE-1 | 1.09 ± 1.58 | 2.48 ± 2.44 | 4.86 ± 3.23 | 1.11 ± 1.50 | 3.65 ± 3.59 |

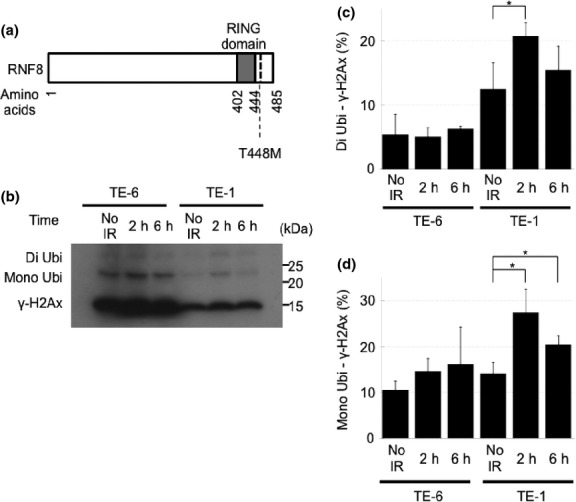

A novel mutation in the RNF8 gene, and the reduced ability of TE-6 cells to polyubiquitinate γ-H2AX

To identify the molecular mechanism underlying the impaired DNA repair in TE-6 cells, we performed whole-exome sequencing of TE-6 and TE-1 cells and selected the DNA repair-related genes that were mutated in the genomic DNA of TE-6 cells but not TE-1 cells. In total, 16 722 and 16 543 single nucleotide variants (SNV) were identified from the exomes of TE-1 and TE-6 cells, respectively (Tables S1 and S2). Another 260 and 240 indels were identified from TE-1 and TE-6 cells, respectively. To reduce the probable germline variants, the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that were registered in the dbSNP and in-house Japanese SNP databases were eliminated. Finaly, 606 SNVs and 118 indels were exclusively identified in the TE-6 cells. Among these mutations were hits in six genes (listed in Table 3) that are related to DNA repair. We further evaluated the impact of amino acid substitutions using the Polyphen2 prediction program; we focused in particular on the T448M missense mutation of RNF8, which is an E3-ligase polyubiquitylating γ-H2AX. The T448M mutation was close to the RING domain (Fig. 7a). To assess the ubiquitylation status of γ-H2AX, we examined X-ray-irradiated TE-6 and TE-1 cells by Western blotting (Fig. 7b). In the TE-1 cells, the levels of mono- and di-ubiquitinated γ-H2AX were increased at 2 h after irradiation and decreased at 6 h after irradiation. Meanwhile, no significant increase in ubiquitination was observed in the TE-6 cells (Fig. 7b–d).

Table 3.

Mutations in the DNA repair-related genes uniquely identified in the exome of TE-6 cells

| Novel mutations of DNA repair involved genes of TE-6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Chr. | Position | Base change | Variant frequency (%) | Amino acid alteration | PolyPhen2 prediction |

| RNF8 | 6 | 37349032 | C>T | 100 | T448M | Probably damaging |

| CHAF1A | 19 | 4429530 | G>A | 87 | R567Q | Probably damaging |

| CEP164 | 11 | 117222670 | A>G | 88.9 | D120G | Probably damaging |

| CLSPN | 1 | 36217027 | C>T | 19.4 | A618T | Benign |

| POLK | 5 | 74865291 | A>G | 55 | I128V | Benign |

| ATRX | X | 76952184 | G>A | 100 | S84L | Benign |

Fig. 7.

A novel mutation in the RNF8 gene and the reduced ability of TE-6 cells to polyubiquitinate γ-H2AX. (a) The structure of RNF8 protein and a newly identified T448M amino acid-substitution mutation. (b) Western blot analysis of γ-H2Ax in TE-6 and TE-1 cells treated with 2 Gy of X-rays. (c) The proportion of diubiquitinated γ-H2Ax standardized to non-ubiquitinated γ-H2Ax. The data represent the averages and standard deviations of three independent experiments. (d) The proportion of monoubiquitinated γ-H2Ax standardized to non-ubiquitinated γ-H2Ax. The data represent the averages and standard deviations of three independent experiments.

Discussion

To date, the anti-tumor effects of PARP inhibitors to ESCC have not been evaluated both in vitro and in vivo. In this study, we identified TE-6 cells as AZD2281-sensitive cell line for the first time. The following findings support the idea that the PARP inhibitor induced growth retardation in the DSB repair-impaired background of TE-6 cells: (i) AZD2281 induced the accumulation of DNA damage, as evaluated by γ-H2AX expression levels. (ii) AZD2281 induced the accumulation of a tetraploid cell population in a time-dependent manner, consistent with previous reports that cells with accumulated unrepaired DSBs caused in every S-phase are arrested at G2/M boundary.(27) (iii) Sustained damage to DNA, the attenuated ubiquitination of γ-H2AX and a defect in DSB repair nuclear foci formation under X-ray irradiation suggest that TE-6 cells have an impaired DNA repair ability.

Several genomic biomarkers that predict the efficacy of PARP inhibitors have been identified. Though the presence or absence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 alterations most strikingly distinguishes the PARP inhibitor-sensitive cells and patients, no pathogenetic mutations in either gene were identified in the TE-6 cells (Table S1). Consistent with this, expression of BRCA1 and BRCA 2 proteins were not reduced in TE-6 cells (Fig. S3a,b). The alteration of other genes, such as 53BP1, RAD51, PTEN and USP11, also reportedly affects the sensitivity to PARP inhibitors.(18,28–32) To identify the genomic events corresponding to the AZD2281 sensitivity of TE-6 cells, we performed whole-exome sequencing. Because a paired non-tumor genome is not available for the TE-series cells, we subtracted previously identified germline variants from our set of total SNVs and indels to enrich for potential somatic mutations. Among the remaining mutations, we focused on those located in the genes encoding DNA repair-related proteins and identified a novel mutation of RNF8. RNF8 is an E3-ligase targeting γ-H2AX that accumulates at DNA DSBs and recruits repair proteins, including 53BP1 and RAD51.(33–35) It was reported that RNF8−/− p53−/− mice had increased levels of genomic instability and a remarkably elevated tumor incidence compared to p53−/− mice,(36) that the knockdown of RNF8 sensitized cells to ionizing radiation, and that disruption of the RING domains of RNF8 impaired DSB-associated ubiquitylation and inhibited retention of 53BP1 and BRCA1 at the DSBs sites.(33) The PolyPhen-2 program predicts a probable deleterious impact of the T448M substitution on the structure and function of RNF8. Although the effect of the T448M mutation on the polyubiquitination ability of RNF8 has not yet been confirmed, the observation that the increase in ubiquitination after X-ray irradiation in the TE-6 cells was less than that of the TE-1 cells suggests that RNF8 is impaired in the TE-6 cells. We hypothesized that this mutation might affect the polyubiquitination ability of RNF8 and, as a result, contribute to the DSB repair defect to some extent. The impact of the mutation or loss of RNF8 to PARP inhibitor sensitivity has to be further evaluated.

Whether RNF8 is the only factor contributing to TE-6 sensitivity should be carefully considered. The anti-tumor effect of PARP inhibitors is obviously determined by the BRCA1 or BRCA2 status in ovarian and breast cancers.(37) Meanwhile, the sensitivity of the TE-series cells to AZD2281 is altered by gradation and most cells exhibited intermediate sensitivity. It may suggest that the AZD2281 sensitivity was regulated by multiple molecular mechanisms in each cell line rather than a single molecule. This multiplicity might make it difficult to identify the distinctive genomic biomarkers of PARP inhibitor sensitivity in ESCC.

We noticed a strong correlation between AZD2281 sensitivity and γ-H2Ax levels in the cells without treatment; this effect might represent the extent of baseline DNA damage. Double strand breaks regularly occur in proliferating cells because topoisomerases bind to DNA and cut the phosphate backbone of the DNA during DNA replication. Though these DSBs are properly repaired in non-tumor cells, it is plausible that unrepaired DNA remains in tumor cells with impaired DSB repair, such as the TE-6 cells. Once a correlation between the baseline level of γ-H2Ax expression and DSB repair defect is further confirmed, the amount of γ-H2Ax in a tumor tissue sample could be a reasonable biomarker for selecting preferable patients for PARP inhibitor therapy. Further clinical and biological studies of this effect are warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Hiroko Onozuka for helpful discussions and technical support. This work was supported by the National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund (23-A-8, 15) and a grant for the Third Term Comprehensive 10-year Strategy for Cancer Control from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (H22-033).

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Materials and methods.

Fig. S1. Effect of AZD2281 on the colony formation of TE-8, TE-10, TE-4, TE-11, TE-14, TE-9 and HCC1937 cells.

Fig. S2. Effect of BSI-201 on the colony formation of TE-1 and TE-6 cells.

Fig. S3. DNA ploidy of TE-1 andTE-6 cells treated with AZD2281 for 12 h.

Fig. S4. Expression of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins in TE-series cells.

Fig. S5. Expression of the 53BP1 and RAD51 proteins in TE-1 and TE-6 cells.

Table S1 Summary of the whole exome sequencing data of TE-1 cells.

Table S2 Summary of the whole exome sequencing data of TE-6 cells.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jamieson GG, Mathew G, Ludemann R, Wayman J, Myers JC, Devitt PG. Postoperative mortality following oesophagectomy and problems in reporting its rate. Br J Surg. 2004;91:943–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Müller JM, Erasmi H, Stelzner M, Zieren U, Pichlmaier H. Surgical therapy of oesophageal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1990;77:845–57. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800770804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang X, Watson DI, Jamieson GG, Lally C, Bessell JR, Devitt PG. Outcome of oesophagectomy for adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and oesophagogastric junction. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:513–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crumley AB, Going JJ, McEwan K, et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection for gastroesophageal cancer in a U.K. population. Long-term follow-up of a consecutive series. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:543–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis JJ, Rubenstein JH, Singal AG, Elmunzer BJ, Kwon RS, Piraka CR. Factors associated with esophageal stricture formation after endoscopic mucosal resection for neoplastic Barrett's esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:753–60. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kakushima N, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of esophageal squamous cell neoplasms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:688–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herskovic A, Martz K, al-Sarraf M, et al. Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone in patients with cancer of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1593–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199206113262403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.al-Sarraf M, Martz K, Herskovic A, et al. Progress report of combined chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in patients with esophageal cancer: an intergroup study. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:277–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ame JC, Spenlehauer C, de Murcia G. The PARP superfamily. BioEssays. 2004;26:882–93. doi: 10.1002/bies.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallmeier E, Kern SE. Absence of specific cell killing of the BRCA2-deficient human cancer cell line CAPAN1 by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:703–6. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.7.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 2005;434:913–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venkitaraman AR. Cancer susceptibility and the functions of BRCA1 and BRCA2. Cell. 2002;108:171–82. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00615-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weston VJ, Oldreive CE, Skowronska A, et al. The PARP inhibitor olaparib induces significant killing of ATM-deficient lymphoid tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2010;116:4578–87. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-265769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williamson CT, Muzik H, Turhan AG, et al. ATM deficiency sensitizes mantle cell lymphoma cells to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:347–57. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dedes KJ, Wetterskog D, Mendes-Pereira AM, et al. PTEN deficiency in endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinomas predicts sensitivity to PARP inhibitors. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:53–75. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McEllin B, Camacho CV, Mukherjee B, et al. PTEN loss compromises homologous recombination repair in astrocytes: implications for glioblastoma therapy with temozolomide or poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5457–64. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiltshire TD, Lovejoy CA, Wang T, Xia F, O'Connor MJ, Cortez D. Sensitivity to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibition identifies ubiquitin-specific peptidase 11 (USP11) as a regulator of DNA double-strand break repair. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14565–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.104745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akbari MR, Malekzadeh R, Lepage P, et al. Mutations in Fanconi anemia genes and the risk of esophageal cancer. Hum Genet. 2011;129:573–82. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-0951-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenberg PS, Alter BP, Ebell W. Cancer risks in Fanconi anemia: findings from the German Fanconi Anemia Registry. Haematologica. 2008;93:511–7. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stransky N, Egloff AM, Tward AD, et al. The mutational landscape of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Science. 2011;333:1157–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1208130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drew Y, Mulligan EA, Vong WT, et al. Therapeutic potential of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor AG014699 in human cancers with mutated or methylated BRCA1 or BRCA2. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:334–46. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakai W, Swisher EM, Karlan BY, et al. Secondary mutations as a mechanism of cisplatin resistance in BRCA2-mutated cancers. Nature. 2008;451:1116–20. doi: 10.1038/nature06633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodrigue A, Lafrance M, Gauthier MC, et al. Interplay between human DNA repair proteins at a unique double-strand break in vivo. EMBO J. 2006;25:222–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mochan TA, Venere M, DiTullio RA, Jr, Halazonetis TD. 53BP1, an activator of ATM in response to DNA damage. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:945–52. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baumann P, West SC. Role of the human RAD51 protein in homologous recombination and double-stranded-break repair. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:247–51. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–21. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bunting SF, Callén E, Wong N, et al. 53BP1 inhibits homologous recombination in Brca1-deficient cells by blocking resection of DNA breaks. Cell. 2010;141:243–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCabe N, Turner NC, Lord CJ, et al. Deficiency in the repair of DNA damage by homologous recombination and sensitivity to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8109–15. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mendes-Pereira AM, Martin SA, Brough R, et al. Synthetic lethal targeting of PTEN mutant cells with PARP inhibitors. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1:315–22. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turner NC, Ashworth A. Biomarkers of PARP inhibitor sensitivity. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:283–6. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1375-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X, Weaver DT. The ups and downs of DNA repair biomarkers for PARP inhibitor therapies. Am J Cancer Res. 2011;1:301–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mailand N, Bekker-Jensen S, Faustrup H, et al. RNF8 ubiquitylates histones at DNA double-strand breaks and promotes assembly of repair proteins. Cell. 2007;131:887–900. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bekker-Jensen S, Mailand N. Assembly and function of DNA double-strand break repair foci in mammalian cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:1219–28. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu CS, Truong LN, Aslanian A, et al. The RING finger protein RNF8 ubiquitinates Nbs1 to promote DNA double-strand break repair by homologous recombination. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:43984–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.421545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halaby MJ, Hakem A, Li L, et al. Synergistic interaction of Rnf8 and p53 in the protection against genomic instability and tumorigenesis. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:123–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Materials and methods.

Fig. S1. Effect of AZD2281 on the colony formation of TE-8, TE-10, TE-4, TE-11, TE-14, TE-9 and HCC1937 cells.

Fig. S2. Effect of BSI-201 on the colony formation of TE-1 and TE-6 cells.

Fig. S3. DNA ploidy of TE-1 andTE-6 cells treated with AZD2281 for 12 h.

Fig. S4. Expression of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins in TE-series cells.

Fig. S5. Expression of the 53BP1 and RAD51 proteins in TE-1 and TE-6 cells.

Table S1 Summary of the whole exome sequencing data of TE-1 cells.

Table S2 Summary of the whole exome sequencing data of TE-6 cells.