Abstract

Gastric gland mucin secreted from the lower portion of the gastric mucosa contains unique O-linked oligosaccharides having terminal α1,4-linked N-acetylglucosamine (αGlcNAc) residues largely attached to a MUC6 scaffold. Previously, we generated A4gnt-deficient mice, which totally lack αGlcNAc, and showed that αGlcNAc functions as a tumor suppressor for gastric cancer. Here, to determine the clinicopathological significance of αGlcNAc in gastric carcinomas, we examined immunohistochemical expression of αGlcNAc and mucin phenotypic markers including MUC5AC, MUC6, MUC2, and CD10 in 214 gastric adenocarcinomas and compared those expression patterns with clinicopathological parameters and cancer-specific survival. The αGlcNAc loss was evaluated in MUC6-positive gastric carcinoma. Thirty-three (61.1%) of 54 differentiated-type gastric adenocarcinomas exhibiting MUC6 in cancer cells lacked αGlcNAc expression. Loss of αGlcNAc was significantly correlated with depth of invasion, stage, and venous invasion by differentiated-type adenocarcinoma. Loss of αGlcNAc was also significantly associated with poorer patient prognosis in MUC6-positive differentiated-type adenocarcinoma. By contrast, no significant correlation between αGlcNAc loss and any clinicopathologic variable was observed in undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma. Expression of MUC6 was also significantly correlated with several clinicopathological variables in differentiated-type adenocarcinoma. However, unlike the case with αGlcNAc, its expression showed no correlation with cancer-specific survival in patients. In undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma, we observed no significant correlation between mucin phenotypic marker expression, including MUC6, and any clinicopathologic variable. These results together indicate that loss of αGlcNAc in MUC6-positive cancer cells is associated with progression and poor prognosis in differentiated, but not undifferentiated, types of gastric adenocarcinoma.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, immunohistochemistry, mucin, O-glycan, tumor progression

Gastric cancer is the fourth most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide.1 Despite improvements in surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, survival rates for advanced gastric cancer are poor. Some patients with gastric cancer, even those with the same TNM stage, have different prognoses and treatment responses. Therefore, we need to understand the biology of gastric cancer better to develop more effective treatment. Recent molecular studies have identified multiple factors that modulate tumor progression, invasion, and metastasis formation.2–4

Gastric adenocarcinoma is divided into intestinal and diffuse types using the Lauren classification system,5 or differentiated and undifferentiated types using the Nakamura classification system.6 Both classification systems are based on morphological characteristics relevant largely to gland formation and histogenetic background, and these two types of tumor, that is, intestinal or differentiated types and diffuse or undifferentiated types, are known to emerge from different genetic pathways.6,7 Although various histological types of tumors can be distinguished using standard H&E staining, recent advances in immunohistochemical methods using gastric and small intestinal cell markers have enabled classification of gastric cancer based on different mucin phenotypes.8

The MUC6 glycoprotein is expressed in gastric gland mucous cells, such as mucous neck and pyloric gland cells in the lower layer of the mucosa, whereas the MUC5AC glycoprotein is expressed in surface mucous cells in the upper layer of the mucosa.9,10 Both MUC6 and MUC5AC are commonly used to identify gastric phenotype of tumors. In contrast, MUC2, a marker of intestinal goblet cells,11,12 and CD10, a marker of intestinal absorptive cells,13,14 are used to identify intestinal phenotypes.15 It is suggested that phenotypic marker expression in gastric carcinoma is associated with clinicopathological variables such as cancer survival,16–18 and several groups report that MUC5AC and MUC2 are useful clinically to predict malignancy outcomes.16,17 Others report that downregulation of MUC6 but not of MUC5AC or MUC2 correlates with gastric carcinoma progression.18 Still others have shown that CD10-positive gastric carcinomas tend to invade blood vessels.19,20 Thus, analysis of phenotypic mucin markers represents a promising approach to predicting gastric cancer progression.

Gastric gland mucin secreted from the lower portion of the gastric mucosa contains unique O-linked oligosaccharides (O-glycan) exhibiting terminal α1,4-linked N-acetylglucosamine residues (αGlcNAc) largely attached to a MUC6 scaffold.21,22 Previously, we used expression cloning to isolate a human A4GNT cDNA encoding α1,4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (α4GnT), the enzyme responsible for αGlcNAc biosynthesis.23 We also showed that in vitro αGlcNAc suppresses growth and motility of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori).24 Recently, we generated A4gnt-deficient mice to assess the role of αGlcNAc in vivo.25 Surprisingly, A4gnt null mice developed gastric adenocarcinoma through a hyperplasia–dysplasia–carcinoma sequence in the absence of H. pylori infection. These findings indicate that αGlcNAc loss triggers gastric tumorigenesis.

We also previously reported that gland mucous cells expressing MUC6 in non-neoplastic gastric mucosa also express αGlcNAc.22 By contrast, αGlcNAc expression is reduced in differentiated-type,25–27 but not in undifferentiated-type, gastric adenocarcinoma.26 These findings, coupled with our observations in A4gnt-deficient mice, suggest that αGlcNAc loss is associated with tumorigenesis of differentiated-type but not undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma. However, to date, the clinicopathological significance of αGlcNAc loss in human gastric cancer remains unclear.

In the present study, we examined expression of mucin phenotypic markers and αGlcNAc in 214 gastric carcinomas by immunohistochemical staining in order to assess the clinicopathological significance of mucin expression and further investigate how αGlcNAc loss is associated with tumor progression.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Our series consisted of 214 patients who had undergone gastrectomy for gastric cancer between 2002 and 2005 at Aizawa Hospital, Matsumoto, Japan. The patients included 150 men and 64 women with an age range of 40–90 years. No preoperative radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy had been given. The Ethical Committees of Shinshu University School of Medicine (Matsumoto, Japan) and Aizawa Hospital approved the protocol and use of human materials in this study.

Histopathology

Tissue specimens were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Hematoxylin–eosin and immunohistochemical stainings were carried out on 4-μm serial sections. Tumors were classified as differentiated or undifferentiated types according to the classification of Nakamura et al.6 Pathological diagnosis, tumor invasion depth, lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis, and stage were determined according to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma, 14th edition.28

Immunohistochemistry

Expression of MUC5AC, MUC6, MUC2, CD10, and αGlcNAc was analyzed by immunohistochemistry. Primary antibodies used included anti-MUC5AC (CLH2) (Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) diluted 1/100, anti-MUC6 (CLH5) (Novocastra) diluted 1/200, anti-MUC2 (Ccp58) (Novocastra) diluted 1/200, anti-CD10 (56C6) (Novocastra) diluted 1/100, and anti-αGlcNAc (HIK1083) (Kanto Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) diluted 1/20. Before immunostaining, antigen retrieval was carried out by microwaving tissue sections in 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 1 mM EDTA for 30 min for anti-MUC5AC, anti-MUC6, anti-MUC2, and anti-CD10 antibodies. The secondary antibody was anti-mouse Dako EnVision+ System–HRP Labeled Polymer (Dako North America, Carpinteria, CA, USA). Peroxidase activity was visualized using a diaminobenzidine–H2O2 solution. Controls were undertaken by omitting the primary antibody, and no specific staining was seen. Tissue specimens containing >5% of positively stained carcinoma cells out of the total number of carcinoma cells on the slide were defined as positive, and others were classified as negative according to the criteria of Machida et al.29

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were compared using the χ2-test. When the expected number in any cell was less than five, Fisher's exact test was used. Age and tumor size were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Cancer-specific survival curves were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method,30 and the difference between the curves was evaluated by a log–rank test.31 P-values < 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analysis was carried out using the spss software package (version 21) (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Expression of mucin markers in gastric cancer

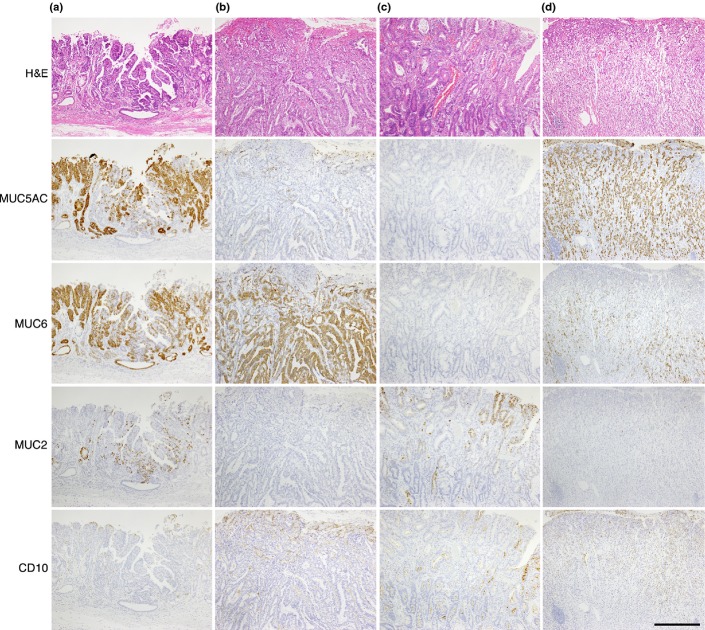

Representative expression of each marker in tumor cells is shown in Figure1. Among 101 differentiated-type adenocarcinomas, 38.6%, 53.4%, 21.7%, and 22.7% were positive for MUC5AC, MUC6, MUC2, and CD10, respectively, Among 113 undifferentiated-type adenocarcinomas, 46%, 42.4%, 23.8%, and 20.3% were positive for MUC5AC, MUC6, MUC2, and CD10, respectively.

Figure 1.

Mucin expression in gastric cancer. (a) MUC5AC-, MUC6-, and MUC2-positive differentiated carcinoma. (b) MUC6-positive differentiated carcinoma. Tumor cells are negative for other markers. (c) MUC2- and CD10-positive differentiated carcinoma. (d) MUC5AC- and MUC6-positive undifferentiated carcinoma. Tumor cells are negative for MUC2 and CD10. Scale bar = 500 μm.

Correlation between clinicopathologic findings and mucin expression in differentiated-type adenocarcinoma

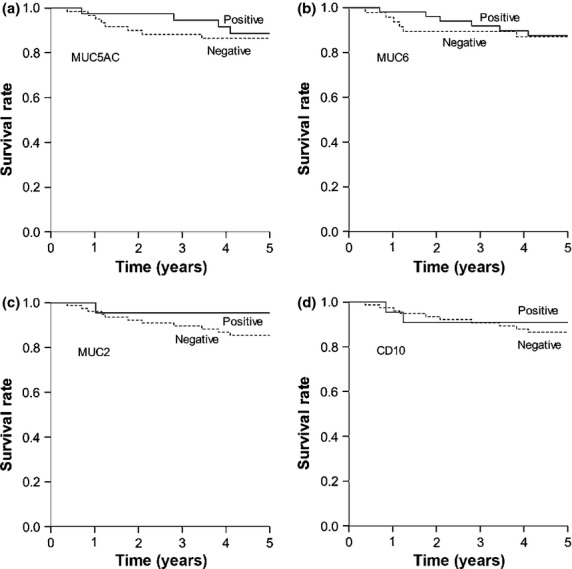

Expression of MUC6 was significantly correlated with depth of invasion, lymph node metastasis, stage, lymphatic invasion, venous invasion, and tumor size (Table1). In addition, MUC2 expression was significantly correlated with venous invasion. However, no significant correlation was seen between MUC5AC or CD10 expression and any variable analyzed. Also, expression of individual mucin phenotypic markers was not associated with 5-year cancer-specific survival rates in patients with differentiated-type adenocarcinoma (Fig.2).

Table 1.

Correlation between clinicopathological variables and phenotypic mucin marker expression in differentiated-type adenocarcinoma of stomach

| Clinicopathological findings | Phenotypic mucin marker expression in tumor cells |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MUC5AC |

MUC6 |

MUC2 |

CD10 |

|||||

| +/− n = 39/62 | P-value | +/− n = 54/47 | P-value | +/− n = 22/79 | P-value | +/− n = 23/78 | P-value | |

| Mean age, years | 67.1/70.8 | 0.056 | 67.6/71.3 | 0.054 | 69.9/69.2 | 0.772 | 71.6/68.7 | 0.205 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male (n = 78) | 31/47 | 0.668 | 44/34 | 0.275 | 17/61 | 1.000 | 20/58 | 0.206 |

| Female (n = 23) | 8/15 | 10/13 | 5/18 | 3/20 | ||||

| Depth of invasion | ||||||||

| T1 (n = 59) | 27/32 | 0.080 | 41/18 | <0.001* | 17/42 | 0.052 | 12/47 | 0.489 |

| T2–4 (n = 42) | 12/30 | 13/29 | 5/37 | 11/31 | ||||

| Lymphatic invasion | ||||||||

| Negative (n = 51) | 23/28 | 0.176 | 36/15 | <0.001* | 15/36 | 0.060 | 13/38 | 0.511 |

| Positive (n = 50) | 16/34 | 18/32 | 7/43 | 10/40 | ||||

| Venous invasion | ||||||||

| Negative (n = 57) | 26/31 | 0.100 | 41/16 | <0.001* | 17/40 | 0.030* | 12/45 | 0.639 |

| Positive (n = 44) | 13/31 | 13/31 | 5/39 | 11/33 | ||||

| Mean tumor size, mm | 40.8/44.0 | 0.862 | 34.6/52.2 | 0.004* | 37.3/44.3 | 0.247 | 42.2/43.0 | 0.900 |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||||

| N0 (n = 69) | 27/42 | 0.876 | 42/27 | 0.028* | 18/51 | 0.194 | 15/54 | 0.716 |

| N1–3 (n = 32) | 12/20 | 12/20 | 4/28 | 8/24 | ||||

| Distant metastasis | ||||||||

| M0 (n = 94) | 38/56 | 0.244 | 52/42 | 0.246 | 21/73 | 1.000 | 22/72 | 1.000 |

| M1 (n = 7) | 1/6 | 2/5 | 1/6 | 1/6 | ||||

| Stage | ||||||||

| I + II (n = 74) | 29/45 | 0.844 | 45/29 | 0.014* | 19/55 | 0.173 | 16/58 | 0.648 |

| III + IV (n = 27) | 10/17 | 9/18 | 3/24 | 7/20 | ||||

P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. +, positive; −, negative.

Figure 2.

Cancer-specific survival in 101 patients with differentiated-type carcinoma based on phenotypic marker expression: (a) MUC5AC, (b) MUC6, (c) MUC2, and (d) CD10. For each marker, there was no significant difference between survival rates of patients whose tumors were positive or negative for the marker (MUC5AC, P = 0.303; MUC6, P = 0.307; MUC2, P = 0.387; and CD10, P = 0.470).

Correlation between clinicopathologic findings and mucin expression in undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma

In undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma, no significant correlations were observed between mucin marker expression and any clinicopathologic variable analyzed (Table2). Mucin marker expression was also not associated with 5-year cancer-specific survival in patients with undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma (Fig.3).

Table 2.

Correlation between clinicopathological variables and phenotypic mucin marker expression in undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma of stomach

| Clinicopathological findings | Phenotypic marker expression in tumor cells |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MUC5AC |

MUC6 |

MUC2 |

CD10 |

|||||

| +/− n = 52/61 | P-value | +/− n = 48/65 | P-value | +/− n = 27/86 | P-value | +/− n = 23/90 | P-value | |

| Mean age, years | 65.7/68.3 | 0.207 | 65.7/68.2 | 0.232 | 67.0/67.2 | 0.938 | 71.6/68.7 | 0.706 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male (n = 72) | 34/38 | 0.734 | 28/44 | 0.306 | 15/57 | 0.312 | 15/57 | 0.867 |

| Female (n = 41) | 18/23 | 20/21 | 12/29 | 8/33 | ||||

| Depth of invasion | ||||||||

| T1 (n = 42) | 23/19 | 0.151 | 22/20 | 0.101 | 13/29 | 0.176 | 8/34 | 0.791 |

| T2–4 (n = 71) | 29/42 | 26/45 | 14/57 | 15/56 | ||||

| Lymphatic invasion | ||||||||

| Negative (n = 39) | 20/19 | 0.415 | 19/20 | 0.330 | 10/29 | 0.752 | 8/31 | 0.976 |

| Positive (n = 74) | 32/42 | 29/45 | 17/57 | 15/59 | ||||

| Venous invasion | ||||||||

| Negative (n = 54) | 28/26 | 0.234 | 26/28 | 0.243 | 17/37 | 0.070 | 10/44 | 0.643 |

| Positive (n = 59) | 24/35 | 22/37 | 10/49 | 13/46 | ||||

| Mean tumor size, mm | 66.4/52.2 | 0.482 | 63.3/55.4 | 0.754 | 60.4/58.2 | 0.496 | 55.1/59.7 | 0.847 |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||||

| N0 (n = 50) | 25/25 | 0.449 | 25/25 | 0.150 | 12/38 | 0.981 | 8/42 | 0.306 |

| N1–3 (n = 63) | 27/36 | 23/40 | 15/48 | 15/48 | ||||

| Distant metastasis | ||||||||

| M0 (n = 102) | 50/52 | 0.062 | 45/57 | 0.349 | 26/76 | 0.455 | 21/81 | 1.000 |

| M1 (n = 11) | 2/9 | 3/8 | 1/10 | 2/9 | ||||

| Stage | ||||||||

| I + II (n = 65) | 30/35 | 0.973 | 30/35 | 0.358 | 16/49 | 0.834 | 13/52 | 0.913 |

| III + IV (n = 48) | 22/26 | 18/30 | 11/37 | 10/38 | ||||

+, positive; −, negative.

Figure 3.

Cancer-specific survival in 113 patients with undifferentiated-type carcinoma based on marker expression: (a) MUC5AC, (b) MUC6, (c) MUC2, and (d) CD10. For each marker, there was no significant difference between survival rates of patients whose tumors were positive or negative for the marker (MUC5AC, P = 0.753; MUC6, P = 0.226; MUC2, P = 0.745; and CD10, P = 0.328).

Expression of αGlcNAc in MUC6-positive gastric cancer

As αGlcNAc is attached to MUC6 in the normal gastric mucosa,22 we tested whether the glycan could be eliminated from gastric cancer cells expressing MUC6 using immunohistochemistry. Fifty-five of 102 (53.9%) MUC6-positive gastric cancers, including differentiated-type and undifferentiated-type adenocarcinomas, lacked αGlcNAc expression (Table3). In addition, αGlcNAc expression in MUC6-positive adenocarcinomas was not significantly correlated with differentiated or undifferentiated tumor types (P = 0.12). However, in the case of signet ring cell carcinoma, a subtype of undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma, only 6 (26.1%) of 23 patients lacked αGlcNAc expression, compared with differentiated-type adenocarcinoma (P = 0.0049).

Table 3.

Correlation between clinicopathological variables and α1,4-linked N-acetylglucosamine (αGlcNAc) expression in MUC6-positive tumor cells from gastric adenocarcinoma

| Clinicopathological findings | Differentiated-type αGlcNAc |

Undifferentiated-type αGlcNAc |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/− n = 21/33 | P-value | +/− n = 26/22 | P-value | |

| Mean age, years | 65.5/69.0 | 0.127 | 64.3/67.4 | 0.281 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male (n = 72) | 18/26 | 0.723 | 13/15 | 0.249 |

| Female (n = 30) | 3/7 | 13/7 | ||

| Depth of invasion | ||||

| T1 (n = 63) | 20/21 | 0.009* | 14/8 | 0.259 |

| T2–4 (n = 39) | 1/12 | 12/14 | ||

| Lymphatic invasion | ||||

| Negative (n = 55) | 17/19 | 0.138 | 13/6 | 0.144 |

| Positive (n = 47) | 4/14 | 13/16 | ||

| Venous invasion | ||||

| Negative (n = 67) | 20/21 | 0.009* | 16/10 | 0.384 |

| Positive (n = 35) | 1/12 | 10/12 | ||

| Mean tumor size, mm | 27.0/39.5 | 0.082 | 67.0/58.9 | 0.828 |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| N0 (n = 67) | 18/24 | 0.329 | 14/11 | 1.000 |

| N1–3 (n = 35) | 3/9 | 12/11 | ||

| Distant metastasis | ||||

| M0 (n = 97) | 21/31 | 0.516 | 25/20 | 0.587 |

| M1 (n = 5) | 0/2 | 1/2 | ||

| Stage | ||||

| I + II (n = 75) | 21/24 | 0.009* | 19/11 | 0.138 |

| III + IV (n = 27) | 0/9 | 7/11 | ||

P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. +, positive; −, negative.

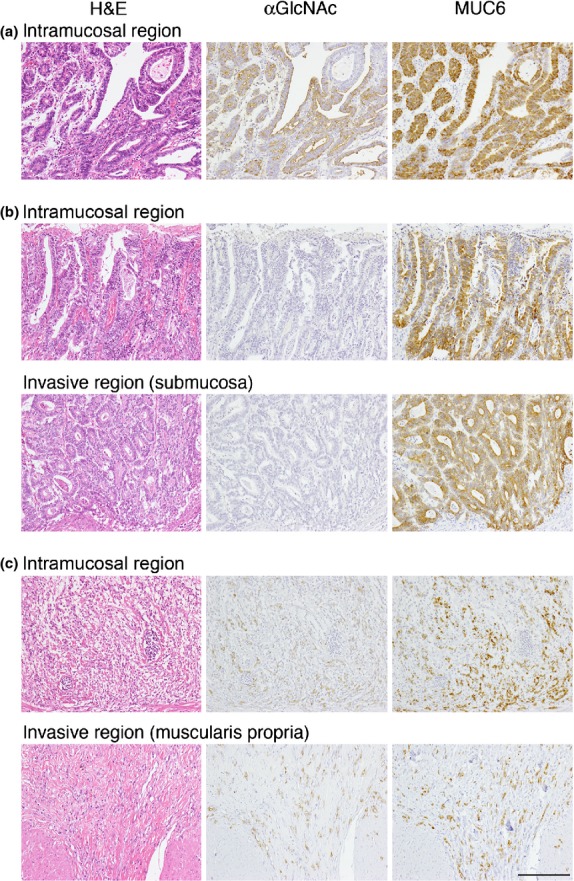

Expression of αGlcNAc in gastric cancer was heterogeneous, irrespective of the histological types. As shown previously,25,32 and further confirmed here, αGlcNAc-positive cancer cells tended to be located in the lower layer of the gastric mucosa rather than in the upper layer, regardless of differentiated or undifferentiated types (Fig.4a,c). Once the cancer cells invaded beyond the muscularis mucosae, αGlcNAc-positive cancer cells were irregularly distributed throughout carcinoma tissues, and the expression levels of αGlcNAc in the invasive region tended to mirror the expression levels of the glycan in the intramucosal cancer region within the same tumor (Fig.4b,c).

Figure 4.

Expression of MUC6 and α1,4-linked N-acetylglucosamine (αGlcNAc) by gastric cancer cells in intramucosal and invasive regions of tumors. In tumor (a), cancer cells were restricted to the gastric mucosa; in tumors (b) and (c), cancer cells invaded beyond the muscularis mucosae. Tumors (a), (b), and (c) are derived from the same patients’ tumors (a), (b), and (d) shown in Figure1, respectively. Scale bar = 200 μm.

Correlation between clinicopathological variables and αGlcNAc expression in differentiated-type adenocarcinoma expressing MUC6 in cancer cells

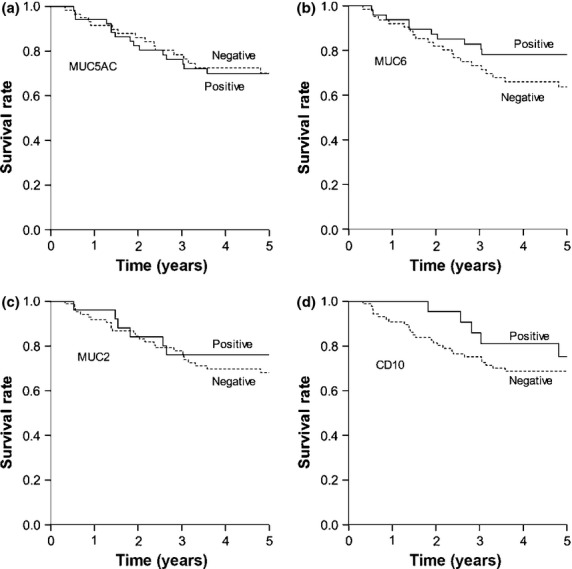

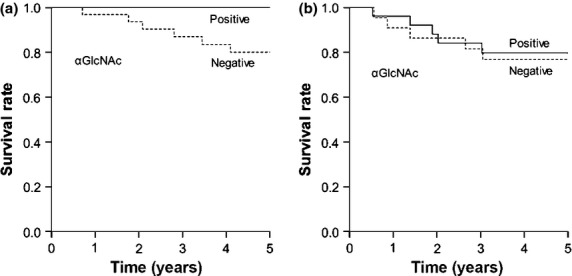

Of samples from 54 patients with differentiated-type gastric adenocarcinoma showing MUC6-positivity in tumor cells, 33 (61.1%) lacked αGlcNAc expression (Table3). Notably, αGlcNAc expression was inversely correlated with depth of invasion, stage, and venous invasion. More importantly, analysis of 5-year cancer-specific survival rates of patients with MUC6-positive cancer cells revealed that individuals with αGlcNAc-negative tumors had a significantly poorer outcome than those showing αGlcNAc-positive tumors (P = 0.048) (Fig.5a).

Figure 5.

Cancer-specific survival in patients with MUC6-positive gastric cancer based on α1,4-linked N-acetylglucosamine (αGlcNAc) expression. (a) In MUC6-positive differentiated-type adenocarcinoma, patients with αGlcNAc-negative tumors had a significantly poorer outcome than patients with αGlcNAc-positive tumors (P = 0.048). (b) In MUC6-positive undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma, there was no significant difference between patient survival rate and the presence or absence of αGlcNAc in tumors (P = 0.549).

Correlation between clinicopathological variables and αGlcNAc expression in undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma showing MUC6-positive cancer cells

As shown in Table3, 22 of 48 (45.8%) MUC6-positive undifferentiated-type adenocarcinomas did not express αGlcNAc. In undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma, no significant correlation was found between αGlcNAc expression and any variable examined, and αGlcNAc status in tumor cells had no significant effect on 5-year cancer-specific survival rates in patients (P = 0.549) (Fig.5b).

Discussion

In the present study, we showed that αGlcNAc loss in MUC6-positive gastric carcinoma cells was significantly correlated with depth of invasion, stage, and venous invasion in differentiated-type but not undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma. More importantly, αGlcNAc loss was associated with significantly poorer survival in patients with the MUC6-positive differentiated-type adenocarcinoma. These results suggest that αGlcNAc loss promotes progression of differentiated-type adenocarcinoma in humans. This conclusion is consistent with our previous study showing that mice deficient in A4gnt in gastric gland mucous cells (which lack αGlcNAc) develop differentiated-type but not undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma.25 Microarray and quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the gastric mucosa of those mutant mice revealed upregulation of genes encoding inflammatory chemokine ligands, proinflammatory cytokines, and growth factors, such as Ccl2, Cxcl1, Cxcl5, Il-11, and Hgf. Chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) attracts tumor-associated macrophages,33 and Ohta et al.34 have reported that CCL2 expression in tumor cells is correlated with depth of tumor invasion and increased microvessel density and macrophage infiltration. Those authors conclude that CCL2 produced by human gastric carcinoma cells functions in angiogenesis through macrophage recruitment and activation. The CXC chemokines CXCL1/CXCL5 are potent angiogenic factors,33 and Verbeke et al.35 showed that CXC chemokines including CXCL1/CXCL5 facilitate tumor progression. Nakayama et al.36 observed that interleukin-11 expression is significantly higher in differentiated compared to undifferentiated types of adenocarcinoma. That group also reported that interleukin-11 functions in gastric carcinoma progression. Furthermore, Mohri et al.37 suggest that hepatocyte growth factor is an important prognostic determinant in gastric cancer. Thus, all of these factors likely promote tumor-promoting inflammation. Accordingly, our results suggest that αGlcNAc loss is related to gastric cancer progression in inflammation-related pathways. It remains to be determined how αGlcNAc loss in gastric cancer promotes tumor-promoting inflammation in the stomach.

It is generally thought that intestinal or differentiated types of adenocarcinoma emerge from gastric mucosa with intestinal metaplasia, whereas diffuse or undifferentiated types of adenocarcinoma arise from ordinary gastric mucosa. However, gastric and intestinal phenotypic markers are widely expressed in gastric cancer, irrespective of histological types.17,19,38 In the present study, altered expression of phenotypic mucin markers was not significantly correlated with histological type (see Tables2). However, it has been suggested that phenotypic mucin marker expression in tumor cells is associated with clinicopathological findings and tumorigenesis in gastric cancer.16–20 Our evaluation of clinicopathological findings and phenotypic mucin marker expression indicates that gastric carcinomas lacking MUC6 expression show deep invasion, frequent lymph node metastasis, high stage, frequent lymphatic and venous invasion, and large tumor size in differentiated-type adenocarcinoma (see Table1). These results concur with the report of Zheng et al.18 showing that MUC6 downregulation correlates with gastric carcinoma progression. Those authors concluded that gastric carcinomas lacking MUC6 expression show aggressive behavior, as mucin loss is an indicator of cellular dedifferentiation or anaplasia. In contrast, other studies indicated no correlation between MUC6 expression and aggressive parameters.39,40 Notably, in the present study, we found that even when cancer cells express MUC6, αGlcNAc loss in MUC6-positive cancer cells is significantly correlated with depth of invasion, venous invasion, stage, and poorer patient prognosis in the case of differentiated-type adenocarcinoma (see Table3, Fig.5a), strongly implying that in humans αGlcNAc acts as a tumor suppressor in this type of cancer. Prospective studies analyzing larger numbers of gastric cancer patients will be of great significance to verify the impact of αGlcNAc loss in MUC6-positive cancer cells in progression of differentiated-type gastric adenocarcinoma.

In conclusion, the present study indicates that αGlcNAc loss in MUC6-positive cancer cells is significantly associated with progression of differentiated-type but not undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Thus, immunohistochemistry for not only MUC6 but also for αGlcNAc may predict progression and prognosis of patients with these types of tumors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research 24390086 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to JN). The authors thank Dr. Elise Lamar for editing the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Funding information

Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (24390086).

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yasui W, Oue N, Aung PP, Matsumura S, Shutoh M, Nakayama H. Molecular-pathological prognostic factors of gastric cancer: a review. Gastric Cancer. 2005;8:86–94. doi: 10.1007/s10120-005-0320-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maehara Y, Kakeji Y, Oda S, Baba H, Sugimachi K. Tumor growth patterns and biological characteristics of early gastric carcinoma. Oncology. 2001;61:102–12. doi: 10.1159/000055360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noto JM, Peek RM. The role of microRNAs in Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis and gastric carcinogenesis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2011;1:21. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2011.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura K, Sugano H, Takagi K. Carcinoma of the stomach in incipient phase: its histogenesis and histological appearances. Gann. 1968;59:251–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saito K, Shimoda T. The histogenesis and early invasion of gastric cancer. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1986;36:1307–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1986.tb02851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tatematsu M, Ichinose M, Miki K, Hasegawa R, Kato T, Ito N. Gastric and intestinal phenotypic expression of human stomach cancers as revealed by pepsinogen immunohistochemistry and mucin histochemistry. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1990;40:494–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1990.tb01591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reis CA, Davvid L, Correa P, et al. Intestinal metaplasia of human stomach displays distinct pattern of mucin (MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC, MUC6) expression. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1003–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Bolos C, Garrido M, Real FX. MUC6 apomucin shows a distinct normal tissue distribution that correlates with Lewis antigen expression in the human stomach. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:723–34. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90379-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carrato C, Balague C, De Bolos C, et al. Differential apomucin expression in normal and neoplastic human gastrointestinal tissues. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:160–72. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baldus SE, Zirbes TK, Engel S, et al. Correlation of the immunohistochemical reactivity of mucin peptide cores MUC1and MUC2 with the histopathological subtype and prognosis of gastric carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 1998;79:133–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980417)79:2<133::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Endoh Y, Tamura G, Motoyama T, Ajioka Y, Watanabe H. Well-differentiated adenocarcinoma mimicking complete-type intestinal metaplasia in the stomach. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:826–32. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sato Y, Itoh F, Hinoda Y, et al. Expression of CD10/neural endopeptidase in normal and malignant tissues of the human stomach and colon. J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:12–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01211181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Namikawa T, Hanazaki K. Mucin phenotype of gastric cancer and clinicopathology of gastric-type differentiated adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4634–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i37.4634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizoshita T, Tsukamoto T, Nakanishi H, et al. Expression of Cdx2 and the phenotype of advanced gastric cancers: relationship with prognosis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2003;129:727–34. doi: 10.1007/s00432-003-0499-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tajima Y, Shimoda T, Nakanishi Y, et al. Gastric and intestinal phenotypic marker expression in gastric carcinomas and its prognostic significance: immunohistochemical analysis of 136 lesions. Oncology. 2001;61:212–20. doi: 10.1159/000055377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng H, Takahashi H, Nakajima T, et al. MUC6 down–regulation correlates with gastric carcinoma progression and a poor prognosis: an immunohistochemical study with tissue microarrays. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2006;132:817–23. doi: 10.1007/s00432-006-0135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tajima Y, Yamazaki K, Nishino N, et al. Gastric and intestinal phenotypic marker expression in gastric carcinomas and recurrence pattern after surgery-immnohistochemical analysis of 213 lesions. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1342–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roviello F, Marrelli D, Manzoni G, et al. Prospective study of peritoneal reccurence after curative surgery for gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1113–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishihara K, Kurihara M, Goso Y, et al. Peripheral α-linked N-accetylglucosamine on the carbohydrate moiety of mucin derived from mammalian gastric glnand mucous cell: epitope recognized by a newly characterized monoclonal antibody. Biochem J. 1996;318(Pt 2):22–8. doi: 10.1042/bj3180409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang MX, Nakayama J, Hidaka E, et al. Immunohistochemical demonstration of α1,4-N-accetylglucosaminyltransferase that forms GlcNAcα1,4Galβ residues in human gastrointestinal mucosa. J Histochem Cytochem. 2001;49:587–96. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakayama J, Yeh JC, Misra AK, Ito S, Katsuyama T, Fukuda M. Expression cloning of a human α1,4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase that forms GlcNAcα1→4Galβ→R, a glycan specifically expressed in the gastric gland mucous cell-type mucin. Proc Natl Acd Sci USA. 1999;96:8991–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawakubo M, Ito Y, Okimura Y, et al. Natural antibiotic function of a human gastric mucin against Helicobacter pylori infection. Science. 2004;305:1003–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1099250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karasawa F, Shiota A, Goso Y, et al. Essential role of gastric gland mucin in preventing gastric cancer in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:923–34. doi: 10.1172/JCI59087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakajima K, Ota H, Sano K, et al. Expression of gastric gland mucous cell-type mucin in normal and neoplastic human tissues. J Histochem Cytocem. 2003;51:1689–98. doi: 10.1177/002215540305101213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiroshita H, Watanabe H, Ajioka Y, Watanabe G, Nishikura K, Kitano S. Re-evaluation of mucin phenotypes of gastric minute well-differentiated-type adenocarcinomas using a series of HGM, MUC5AC, MUC6, M-GGMC, MUC2 and CD10 stains. Pathol Int. 2004;54:311–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2004.01625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma. 14th edn. Tokyo, Japan: Kanehara; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Machida E, Nakayama J, Amano J, Fukuda M. Clinicopathological significance of core 2 β1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase messenger RNA expressed in the pulmonary adenocarcinoma determined by in situ hybridization. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2226–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. II. analysis and examples. Br J Cancer. 1977;35:1–39. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1977.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ota H, Hayama M, Nakayama J, et al. Cell lineage specificity of newly raised monoclonal antibodies against gastric mucins in normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic human tissues and their application to pathology diagnosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;115:69–79. doi: 10.1309/AMUR-K5L3-M2DN-2DK5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mantovani A, Savino B, Locati M, Zammataro L, Allavena P, Bonecchi R. The chemokine system in cancer biology and therapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohta M, Kitadai Y, Tanaka S, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression correlates with macrophage infiltration and tumor vascularity in human gastric carcinomas. Int J Oncol. 2003;22:773–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verbeke H, Geboes K, Van Damme J, Struyf S. The role of CXC chemokines in the transition of chronic inflammation to esophageal and gastric cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1825:117–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakayama T, Yoshizaki A, Izumida S, et al. Expression of interleukin-11 (IL-11) receptor α in human gastric carcinoma and IL-11 upregulates the invasive activity of human gastric carcinoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:825–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohri Y, Miki C, Tanaka K, et al. Clinical correlations and prognostic relevance of tissue angiogenic factors in patients with gastric cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2012;24:610–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toki F, Takahashi A, Aihara R, et al. Relationship between clinicopathological features and mucin phenotypes of advanced gastric adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2764–70. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i22.2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reis CA, David L, Carvalho F, et al. Immunohistochemical study of the expression of MUC6 mucin and co-expression of other secreted mucins (MUC5AC and MUC2) in human gastric carcinomas. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:377–88. doi: 10.1177/002215540004800307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee HS, Lee HK, Kim HS, Yang HK, Kim YI, Kim WH. MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC6 expressions in gastric carcinomas: their roles as prognostic indicators. Cancer. 2001;92:1427–34. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010915)92:6<1427::aid-cncr1466>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]