Abstract

The Sokal and Hasford scores were developed in the chemotherapy and interferon era and are widely used as prognostic indicators in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Recently, a new European Treatment and Outcome Study (EUTOS) scoring system was developed. We performed a multicenter retrospective study to validate the effectiveness of each of the three scoring systems. The study cohort included 145 patients diagnosed with CML in chronic phase who were treated with imatinib. In the EUTOS low- and high-risk groups, the cumulative incidence of complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) at 18 months was 86.9% and 87.5% (P = 0.797) and the 5-year overall survival rate was 92.6% and 93.3% (P = 0.871), respectively. The cumulative incidence of CCyR at 12 months, 5-year event-free survival and 5-year progression-free survival were not predicted using the EUTOS scoring system. However, there were significant differences in both the Sokal score and Hasford score risk groups. In our retrospective validation study, the EUTOS score did not predict the prognosis of patients with CML in chronic phase treated with imatinib.

Keywords: Chronic myeloid leukemia, European Treatment and Outcome Study score, Hasford score, Sokal score, validation

The prognosis of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) was remarkably improved by the introduction of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI).1 In the pre TKI era, the 5-year CML survival rate with interferon and chemotherapy was 57% and 42%, respectively.2 In contrast, first-line therapy with imatinib, a first generation TKI, was associated with a 5-year overall survival (OS) of 83–89%.3,4 The Sokal and Hasford scores were developed in the chemotherapy and interferon era and widely used for predicting the prognosis of patients with CML.5,6 Recently, Hasford et al.7 developed a new scoring system known as the European Treatment and Outcome Study (EUTOS) scoring system, which uses only the basophil count and size of splenomegaly at diagnosis of CML. In this study, 2060 newly diagnosed patients with CML in chronic phase (CP) (CML-CP) who were treated with an imatinib-based regimen7 were examined. In their study, the EUTOS score predicted that 34% of high-risk patients will fail to achieve a complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) in 18 months and the significant difference of progression-free survival (PFS) between the groups was shown. In the present study, we retrospectively evaluated the usefulness of the EUTOS score using data from CML-CP patients.

Materials and Methods

One hundred and forty-five patients with CML-CP who were treated with imatinib and diagnosed between April 2001 and January 2011 at one of seven hospitals of the Yokohama City University Hematological group were assessed. We used the previously defined diagnostic criteria for CML-CP.8 Using the Sokal, Hasford and EUTOS scores, we divided the patients into each risk groups and validated the prognostic power of each of the scoring systems. The calculation forms of each three scoring systems are summarized in Table 1. The Sokal score was calculated using the original formula as follows: Exp 0.0116 × (age in years − 43.4) + 0.0345 × (spleen size − 7.51) + 0.188 × ([platelet count/700]2 − 0.563) + 0.0887 × (blast cell counts − 2.10), where Exp is the exponential function. The Sokal risk scores were designated as follows: low Sokal risk (score <0.8); intermediate risk (score 0.8–1.2); and high Sokal risk (score >1.2). The Hasford score was calculated using the following original formula: 0.666 (when age >50 years) + (0.042 × spleen size) + 1.0956 (when platelet count >1500 × 109/L) + (0.0584 × blast cell counts) + 0.20399 (when basophil counts >3%) + (0.0413 × eosinophil counts) × 100. The Hasford risk score was designated as follows: low Hasford risk (score ≤780); intermediate risk (score 781–1480); and high risk (score >1480). The EUTOS score was calculated as (7 × basophils) + (4 × spleen size) at diagnosis, where the spleen was measured in centimeters below the costal margin and basophils, as a percentage ratio. An EUTOS score of >87 indicated a high risk and ≤87 indicated a low risk.

Table 1.

Calculation form of each scoring system for the Sokal, Hasford and EUTOS scores

| Scoring system | Calculation | Risk definition |

|---|---|---|

| Sokal score5 | Exp 0.0116 × (age − 43.4) + 0.0345 × (spleen − 7.51) + 0.188 × [(platelet count ÷ 700)2 − 0.563] + 0.0887 × (blast cells − 2.10) | Low risk: <0.8 Intermediate risk: 0.8–1.2 High risk: >1.2 |

| Hasford score6 | 0.666 when age ≥50 years + (0.042 × spleen) + 1.0956 when platelet count >1500 × 109/L + (0.0584 × blast cells) + 0.20399 when basophils >3% + (0.0413 × eosinophils) × 100 | Low risk: ≤780 Intermediate risk: 781–1480 High risk: >1480 |

| EUTOS score7 | (Basophils × 7) + (spleen × 4) | Low risk: ≤87 High risk: >87 |

Age is in years. Spleen is in cm below the costal margin. Blast cells, eosinophils and basophils are in percent of peripheral blood differential. EUTOS, European Treatment and Outcome Study; Exp, exponential function.

The institutional review board of Yokohama City University Hospital approved the study and all procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Definitions

A CCyR was defined as the absence of Philadelphia chromosome by G-banding analysis of bone marrow and Philadelphia cells by fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of peripheral blood. Major molecular response (MMR) was defined as the presence of 100 copies/μg of major BCR-ABL mRNA measured by transcription-mediated amplification and hybridization protein assay.9–11

Event-free survival (EFS) was measured from the date of imatinib treatment initiation to the date of the following events: loss of cytogenetic effect (partial cytogenetic response [PCyR] or CCyR); progression to acceleration phase (AP) or blastic phase (BP); or death from any cause. The criteria recommended by the European Leukemia Net (ELN) 2010 were used for the definition of complete hematological response, AP and BP.12 Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from the date of therapy initiation to the date of progression to AP/BP or to the date of death from any cause. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of therapy initiation to the date of death or final follow up (31 January 2012).

Statistical analysis

The EFS, PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier methods and compared using the log-rank test. Cumulative incidence of CCyR and MMR was also compared using the log-rank test. Differences among variables were evaluated using the Fisher's exact test and Mann–Whitney U-test for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)13 and a modified version for R commander designed to add statistical function frequently used in biostatistics.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of patients with CML-CP are shown in Table 2. The median age at diagnosis was 54 years (range, 15–83 years). The median duration from diagnosis to treatment initiation was 14 days (range, 0–285 days). The median follow-up period of the surviving patients was 57 months (range, 9–130 months). The median percentage of basophils was 5% (range, 0–24.5%). Splenomegaly was found in 36 patients and the median length below the costal margin was 0 cm (range, 0–25 cm). The dose of imatinib at initiation was 300 mg/day in five patients (3.4%), 400 mg/day in 139 patients (95.9%) and 600 mg/day in one patient (0.7%). According to the EUTOS score, 129 patients (89%) were determined to have a low risk and 16 patients (11%) were determined to have a high risk. Using the Sokal and Hasford score, 66 and 60 patients, 52 and 72 patients and 27 and 13 patients were divided into low, intermediate and high risk, respectively.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients at diagnosis (n = 145)

| Clinical characteristics | Median (range) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54 (15–83) |

| WBC (/μL) | 36 360 (2877–750 000) |

| Blast (%) | 0 (0–14) |

| Eosinophil (%) | 2.5 (0–13) |

| Basophil (%) | 5 (0–25.5) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.9 (4.1–16.6) |

| Platelet cells (/μL) | 48.5 (11.3–446.0) |

| LDH (/base) | 2.34 (0.76–10.28) |

| Days from diagnosis to start of treatment | 14 (0–285) |

| No. patients (%) | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 88 (60.7) |

| Female | 57 (39.3) |

| Splenomegaly (>10 cm) | |

| Yes | 36 (24.8) |

| No | 109 (75.2) |

| Range (cm) | 0–25 |

| Imatinib dose (mg) | |

| 300 | 5 (3.4) |

| 400 | 139 (95.9) |

| 600 | 1 (0.7) |

| Sokal risk | |

| Low | 66 (45.5) |

| Intermediate | 52 (35.9) |

| High | 27 (18.6) |

| Hasford risk | |

| Low | 60 (41.4) |

| Intermediate | 72 (49.6) |

| High | 13 (9.0) |

| EUTOS risk | |

| Low | 129 (89.0) |

| High | 16 (11.0) |

EUTOS, European Treatment and Outcome Study; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; WBC, white blood cell.

Outcome

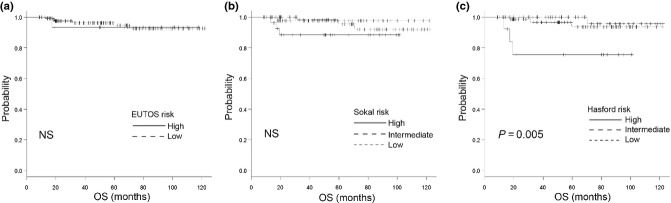

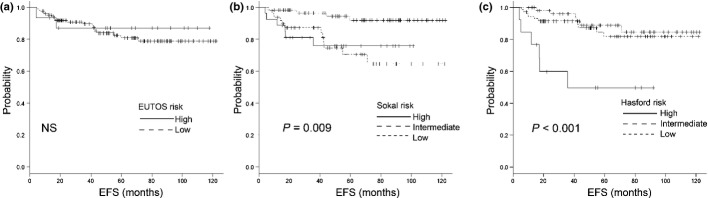

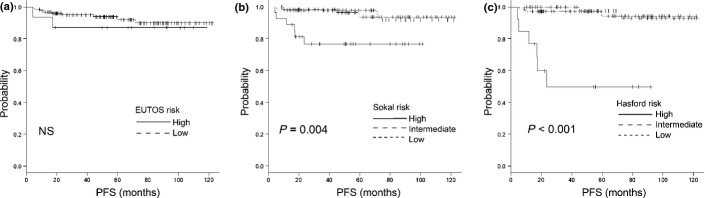

The response rates to treatment and outcomes according to each of the scoring systems are listed in Table 3 and Figures 1–3. The cumulative incidence of CCyR at 12 and 18 months, cumulative incidence of MMR at 12 and 18 months, EFS, PFS and OS are also shown. The cumulative incidence of CCyR at 18 months was 86.9% and 87.5% in the EUTOS low- and high-risk groups (P = 0.797), 93.1%, 85.2% and 69.2% in the Sokal low-, intermediate- and high-risk groups (P = 0.002) and 92.2%, 87.2% and 75% in the Hasford low-, intermediate- and high-risk groups (P = 0.002), respectively. According to risk stratifications, there were significant differences in CCyR prediction between the Sokal and Hasford risk groups, but no significant difference among the EUTOS score risk groups. The cumulative incidence of CCyR at 12 months was validated using the Sokal and Hasford scores (P = 0.012 and P < 0.001, respectively), but not by the EUTOS score (P = 0.828). For the cumulative incidence of MMR at 18 months, there were no significant differences between the three risk categories (Table 3). The 5-year OS rates were 92.6% and 93.3% (P = 0.871) in the EUTOS low- and high-risk groups, 95.4%, 100% and 88.4% (P = 0.216) in the Sokal low-, intermediate- and high-risk groups and 100%, 93.7% and 75.5% (P = 0.005) in the Hasford low-, intermediate- and high-risk groups, respectively (Fig. 1a–c). The 5-year PFS rates were 92.1% and 87.1% (P = 0.5) in the EUTOS low- and high-risk groups, 96.4%, 98% and 76.7% (P = 0.004) in the Sokal low-, intermediate- and high-risk groups and 97.5%, 94.2% and 49.9% (P < 0.001) in the Hasford low-, intermediate- and high-risk groups, respectively (Fig. 2a–c). The 5-year EFS rates were 80.9% and 87.9% (P = 0.66) in the EUTOS low- and high-risk groups, 91.9%, 70.6% and 76.1% (P = 0.009) in the Sokal low-, intermediate- and high-score groups and 88.9%, 81.8% and 49.9% (P < 0.001) in the Hasford low-, intermediate- and high-risk groups, respectively (Fig. 3a–c).

Table 3.

Comparison of Sokal, Hasford and EUTOS scores for cumulative incidence of complete cytogenetic response at 12 and 18 months and major molecular response at 18 months

| No. (%) | 12m-CCyR (%) | 18m-CCyR (%) | 18m-MMR (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUTOS | P = 0.828 | P = 0.797 | P = 0.243 | |

| Low | 129 (89.0) | 80.4 | 86.9 | 50.4 |

| High | 16 (11.0) | 81.3 | 87.5 | 75.0 |

| Sokal | P = 0.012 | P = 0.002 | P = 0.493 | |

| Low | 66 (45.5) | 87.9 | 93.1 | 57.6 |

| Intermediate | 52 (35.9) | 78.8 | 85.2 | 50.0 |

| High | 27 (18.6) | 63.0 | 69.2 | 48.1 |

| Hasford | P < 0.001 | P = 0.015 | P = 0.375 | |

| Low | 60 (41.4) | 88.3 | 92.2 | 56.8 |

| Intermediate | 72 (49.7) | 77.8 | 87.2 | 52.8 |

| High | 13 (8.9) | 53.8 | 75.0 | 38.5 |

| All patients | 145 | 80.3 | 86.9 | 52.9 |

12m-CCyR, complete cytogenetic response at 12 months; 18m-MMR, major molecular response at 18 months; EUTOS, European Treatment and Outcome Study.

Figure 1.

Overall survival (OS) using (a) the European Treatment and Outcome Study (EUTOS) score, (b) the Sokal score and (c) the Hasford score. There is a significant difference (P = 0.005) in OS between the risk groups according to the Hasford score, but no significant difference according to the EUTOS and Sokal scores. NS, not significant.

Figure 3.

Event-free survival (EFS) using (a) the European Treatment and Outcome Study (EUTOS) score, (b) the Sokal score and (c) the Hasford score. There are significant differences (P = 0.009 and P < 0.001) in EFS between the risk groups according to the Sokal and Hasford scores, respectively. There is no significant difference according to the EUTOS score. NS, not significant.

Figure 2.

Progression-free survival (PFS) using (a) the European Treatment and Outcome Study (EUTOS) score, (b) the Sokal score and (c) the Hasford score. There are significant differences (P = 0.004 and P < 0.001) in PFS between the risk groups according to the Sokal and Hasford scores, respectively. There is no significant difference according to the EUTOS score. NS, not significant.

Discussion

We performed a multicenter retrospective study to validate the effectiveness of the EUTOS, Sokal and Hasford scoring systems. The study cohort included newly diagnosed CML-CP patients who were treated with imatinib. We found that both the Sokal and Hasford scores, but not the EUTOS score, were clinically effective prognostic indicators. The EUTOS score did not predict the CCyR at 12 and 18 months, MMR at 12 and 18 months or EFS, PFS and OS. However, the Sokal and Hasford scores predicted the cumulative incidence of CCyR at 12 and 18 months, 3-year EFS and 3-year PFS. In the data from the present study, the EUTOS high-risk patients did not share the risk group with the other two scoring systems. In detail, there were only four patients whose scores were within all high risks in the three scoring systems. Of the EUTOS high-risk patients (16 patients), eight patients were Sokal high risk and four patients were Hasford high risk. In contrast, the Hasford high-risk patients (13 patients) were all Sokal high risk (data not shown). The factors included in the Sokal and Hasford scores are similar, but the EUTOS score includes only basophil cell count and the size of splenomegary. Age, platelet count and blast cell count, which consist of the Sokal and Hasford scores but are not included in the EUTOS score, might have a prognostic influence on CML patients.

After the development of the EUTOS score, several studies evaluated its clinical significance and reported both negative14,15 and positive16–22 findings.

The original report for the EUTOS scoring system by Hasford et al.7 used data from patients who were participating in clinical trials; therefore, clinical bias of the patient's characteristics or treatment may have influenced the results. However, using data from 1288 CML patients, including those in and out of clinical trials who were treated with first-line imatinib therapy, Hoffmann et al.22 recently reported that the EUTOS scoring system can predict CCyR at 18 months, PFS and OS. The present cohort also included patients who were both in and out of clinical trials, but the EUTOS score did not predict their outcome. The EUTOS score also did not predict the outcome when subanalysis data from the patients included in the clinical trials were used (data not shown).

The end-points for assessment of the EUTOS scoring system differed between reports. Hasford et al.7 used the CCyR at 18 months, which is known to be an early surrogate marker of outcome. In addition to the CCyR at 18 months, we assessed the CCyR at 12 months because it was one of the factors of optimal response according to the 2010 ELN recommendation,9 while EFS, PFS and OS were factors for prognosis. Of the five reports18,20,22 assessing the CCyR at 18 months, including the original report by Hasford et al.7 and the present study, three reports7,20,22 showed significant differences according to the EUTOS scoring system. Therefore, validation of the EUTOS scoring system should be performed using a homogenous end-point.

Reports on the EUTOS score using data from Asian patients are relatively limited. Yahng et al.19 and Than et al.20 reported the use of the EUTOS score in patients from Korea and Singapore, respectively. Yahng et al.19 reported that high-risk patients identified as per the EUTOS score comprised 16.5% of the study population, while Than et al.20 reported a proportion of 31%; the ratios are higher than those of other reports, 5.1–13.2%, including our data of 11%. The cumulative incidence of CCyR at 12 months in the EUTOS low- and high-risk groups was 89% and 57% (P < 0.0001) in the report by Yahng et al.,19 68% and 39% (P = 0.008) in the report by Than et al.20 and 80.4% and 81.3% (P = 0.828) in the present study, respectively. The treatment response rates in the present study are higher than those of Yahng et al.19 and Than et al.20 In addition, in the present study, the treatment responses and outcomes were good even in the EUTOS high-risk group, suggesting that the EUTOS score does not correlate with the prognosis.

Poor patient adherence to the CML treatment therapy might be the predominant reason for the inability to obtain adequate molecular responses.23 Maintaining good adherence to treatment is considered an important therapeutic target.12 Furthermore, evidence suggests that the poor adherence to BCR-ABL inhibitor therapy is associated with reduced efficacy and increased healthcare costs.24 Adherence might overcome the prognostic risk at the diagnosis of CML. Moreover, inter-racial differences in the pharmacokinetics of imatinib have been reported.25 Although not assessed in the present study, these factors might influence the results of validation studies of the scoring systems used in CML.

Currently, the usefulness of the EUTOS score is uncertain. Data in the present study did not validate the effectiveness of the EUTOS score. The small size of the high-risk group in the EUTOS score might be one reason for not predicting the clinical outcomes. To resolve these issues, all CML patients treated with imatinib and 2nd TKI, whether they are included in clinical trials, should be analyzed to validate the EUTOS score. Additionally, the validation of the EUTOS scoring system should be assessed using a homogeneous end-point. Adequate monitoring of adherence to TKI therapy and assessment of racial differences are also needed.

In conclusion, the EUTOS score did not predict the treatment efficacy and outcome in newly diagnosed CML-CP patients treated with imatinib. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use data from Japanese patients.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Funding information

None declared.

References

- 1.Sawyers CL. Chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1330–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904293401706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Trialists' Collaborative Group. Interferon alfa versus chemotherapy for chronic myeloid leukemia: a meta-analysis of seven randomized trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1616–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Druker BJ, Guilhot F, O'Brien SG, et al. Five-year follow up of patients receiving imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2408–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Lavallade H, Apperley JF, Khorashad JS, et al. Imatinib for newly diagnosed patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: incidence of sustained responses in an intention-to-treat analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3358–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sokal JE, Cox EB, Baccarani M, et al. Prognostic discrimination in ‘good-risk’ chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blood. 1984;63:789–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasford J, Pfirrman M, Hehlmann R, et al. A new prognostic score for survival of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with interferon alfa. Writing Committee of the Collaborative CML Prognostic Factors Project Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:850–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.11.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasford J, Baccarian M, Hoffman V, et al. Predicting complete cytogenetic response and subsequent progression-free survival in 2060 patients with CML on imatinib treatment: the EUTOS score. Blood. 2011;118:686–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-319038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kantarjian H, Talpaz M, O'Brien S, et al. Imatinib mesylate for Philadelphia chromosome-positive, chronic-phase myeloid leukemia after failure of interferon-alpha. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2177–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langabeer SE, Gale RE, Harvey RC, et al. Transcription-mediated amplification and hybridisation protection assay to determine BCR-ABL transcript levels in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia. 2002;16:393–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yagasaki F, Niwa T, Abe A, et al. Correlation of quantification of major bcr-abl mRNA between TMA (transcription mediated amplification) method and real-time quantitative PCR. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2009;50:481–7. (In Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohnishi K, Nakaseko C, Takeuchi J, et al. Long-term outcome following imatinib therapy for chronic myelogenous leukemia, with assessment of dosage and blood levels: the JALSG CML202 study. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:1071–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02253.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baccarani M, Cortes J, Pane F, et al. Chronic myeloid leukemia: an update of concepts and management recommendations of European LeukemiaNet. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6041–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:452–8. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin D, Ibrahim AR, Goldman JM, et al. European Treatment and Outcome Study (EUTOS) score for chronic myeloid leukemia still requires more confirmation. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3944–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.6962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jabbour E, Cortes J, Nazha A, et al. EUTOS score is not predictive for survival and outcome in patients with early chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a single institution experience. Blood. 2012;119:4524–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-388967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breccia M, Finsinger P, Loglisci G, et al. The EUTOS score identifies chronic myeloid leukemia patients with poor prognosis treated with imatinib first or second line. Leuk Res. 2012;36:e209–10. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uz B, Buyukasik Y, Atay H, et al. EUTOS CML prognostic scoring system predicts ENL-based ‘event-free survival’ better than Euro/Hasford and Sokal systems in CML patients receiving front-line imatinib mesylate. Hematology. 2013;18:247–52. doi: 10.1179/1607845412Y.0000000071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pagnano KB, Lorand-Metze I, Miranda EC, et al. EUTOS score is predictive of event-free survival, but not for progressive-free and overall survival in patients with early chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia treated with imatinib: a single institute experience. Blood. 2012;120 (ASH abstract no. 1681) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yahng SA, Jang EJ, Choi SY, et al. Comparison of Sokal, Hasford and EUTOS scores in terms of long-term treatment outcome according to the risks in each model: a single center date analyzed in 255 early chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with frontline imatinib mesylate. Blood. 2012;120 (ASH abstract no. 2794) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Than H, Kuan LY, Seow CH, et al. The EUTOS score is highly predictive for clinical outcome and survival in Asian patients with early chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia treated with imatinib. Blood. 2012;120 (ASH abstract no. 3758) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tiribelli M, Bonifacio M, Calistri E, et al. EUTOS score predicts long-term outcome but not optimal response to imatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2013;37:1457–60. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffmann VS, Baccarani M, Lindoerfer D, et al. The EUTOS prognostic score: review and validation in 1288 patients with CML treated frontline with imatinib. Leukemia. 2013;27:2016–22. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marin D, Bazeos A, Mahon FX, et al. Adherence is the clinical factor for achieving molecular response in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia who achieve complete cytogenic response on imatinib. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2381–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jabbour E, Saglio G, Radich J, et al. Adherence to BCR-ABL inhibitors: issues for CML therapy. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2012;12:223–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh O, Chan JY, Lin K, Heng CC, Chowbay B. SLC22A1-ABCB1 haplotype profiles predict imatinib pharmacokinetics in Asian patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e51771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]