Abstract

The fact that various immune cells, including macrophages, can be found in tumor tissue has long been known. With the recent introduction of the novel concept of macrophage differentiation into a classically activated phenotype (M1) and an alternatively activated phenotype (M2), the role of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) is gradually beginning to be elucidated. Specifically, in human malignant tumors, TAMs that have differentiated into M2 macrophages act as “protumoral macrophages” and contribute to the progression of disease. Based on recent basic and preclinical research, TAMs that have differentiated into protumoral or M2 macrophages are believed to be intimately involved in the angiogenesis, immunosuppression, and activation of tumor cells. In this paper, we specifically discuss both the role of TAMs in human malignant tumors and the cell–cell interactions between TAMs and tumor cells.

Keywords: Cancer, CD163, M2, macrophage, TAM

It has long been known that many leukocytes including macrophages are present in tumor tissues and that these cells, together with fibroblasts and vascular endothelial cells, form the tumor microenvironment (Fig.1).1–4 Previously, activated macrophages were believed to exhibit antitumor activity by directly attacking tumor cells in the tumor microenvironment.5 However, many recent studies have indicated the protumoral functions of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), and thus, TAMs are believed to directly or indirectly promote tumor progression.6–8 Great advances have been made in TAM research over the past dozen years or so, with one of the most significant breakthroughs being the development of immunohistochemical methods for identifying TAMs in tumor tissue. Numerous studies using human samples have been carried out using CD68 as a macrophage marker, whereas CD163 and CD204 have been used as markers of M2 macrophages in recent studies.9,10 Although variability is observed according to tumor tissue type and location, over 80% of immunohistochemical studies using various human tumor tissues have shown that higher numbers of TAMs are associated with worse clinical prognosis.9 Supporting these clinical observations, in vitro experiments using human tumor cells and experiments using animal models indicate that TAMs promote tumor cell growth by suppressing antitumor immunity and inducing angiogenesis.11,12

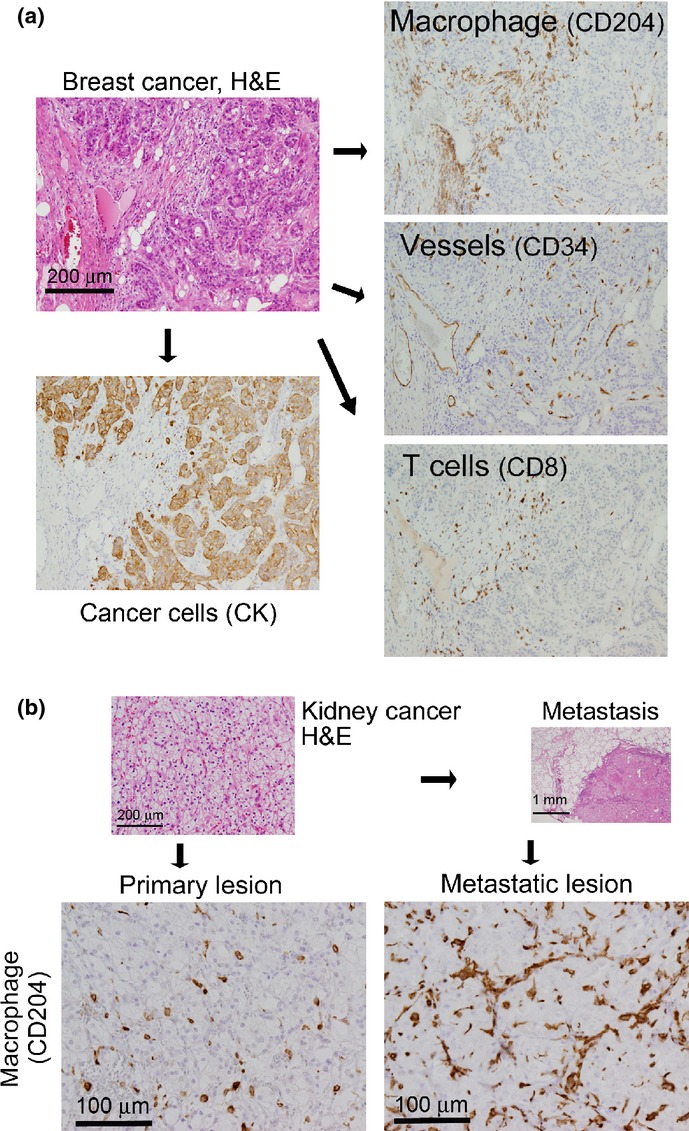

Figure 1.

Tumor microenvironment. (a) Tumor tissue contains not only tumor cells, but also large numbers of normal cells, including tumor-associated macrophages, lymphocytes, blood vessels, and fibroblasts, that affect tumor development in various ways. The photographs show an example of a clinical case of human breast cancer (invasive ductal carcinoma). The relative distributions of the above-mentioned cell types differ by organ and tissue type as well as individual case. CK, cytokeratin. (b) Metastatic tumors contain a larger number of tumor-associated macrophages. The photographs show an example of a clinical case of human kidney cancer (clear cell renal cell carcinoma). The primary tumor tissues and the metastatic (lung) tumors are shown.

As the relationship between TAMs and malignant tumors becomes clearer, TAMs have begun to be seen as the target of new cancer treatments. Clarification of how TAMs are involved in tumor progression and metastasis is anticipated to lead to the development of novel treatments and drugs.

Intratumoral infiltration of TAMs

Intratumoral infiltration of monocytes/macrophages is induced by various chemokines including chemokine (C-C motif) ligand (CCL)2, CCL5, CCL7, and chemokine (C-X3-C motif) ligand (CX3CL)1, as well as cytokines such as macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which are produced by tumor cells.13–15 Subsequent differentiation into TAMs is induced by various factors produced by tumor cells. While the tumor size is small, macrophages from the surrounding tissue accumulate in and around the tumor by tumor cell-derived chemotactic molecules described above, and TAMs derived from the surrounding tissue macrophages account for the majority of TAMs.4,16 As the tumor subsequently increases in size and an intratumoral vascular network forms, monocyte-derived TAMs become the dominant source of TAMs.4,16

Although many macrophage chemotactic factors are secreted by tumor cells, CCL2 and M-CSF are considered to be important molecules involved in macrophage infiltration. CCL2 is expressed in a wide variety of tumor cells, including gliomas, squamous cell carcinoma, ovarian cancer, prostate cancer, lung cancer, cervical cancer, and undifferentiated sarcoma, CCL2 also plays an important role in the intratumoral infiltration of monocytes.13,17 In addition to inducing monocyte infiltration, M-CSF plays a critical role in the differentiation of monocytes into macrophages and, in particular, into M2 macrophages.18–20

Role of TAMs in tumor progression

Based on numerous studies using murine tumor models, activated TAMs were found to produce a variety of angiogenic, immunosuppressive, and growth-related factors.7,8 However, few studies have been carried out using human materials, and thus the detailed mechanisms and molecular characterization of TAMs in human tumors have yet to be described. One method for studying the relationship between TAMs and tumor development is to carry out statistical analysis using clinical data related to survival rates or survival times. Studies comparing TAM infiltration into diseased tissue, using CD68 as a macrophage marker, are summarized in Table1. The majority of studies in human malignant tumors have found that a higher level of TAM infiltration is associated with lower survival rates, and these observations indicate that TAMs may enhance tumor progression. However, other reports in certain types of cancer such as gastric, colon, and prostate cancer, have shown that a higher number of TAM infiltration results in a better outcome.

Table 1.

High numbers of CD68+ tumor-associated macrophages are correlated with clinical prognosis in human malignant tumors

| Tumor type | Favorable prognosis | Poor prognosis |

|---|---|---|

| Epithelial | Gastric cancer (adenocarcinoma)68 Colorectal cancer (adenocarcinoma)71 Prostate cancer (adenocarcinoma)73 |

Uterine cancer (endometrioid adenocarcinoma)69,70 Esophageal cancer (squamous cell carcinoma)72 Liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma)74 Breast cancer (invasive ductal carcinoma)75,76 Thyroid cancer (poorly differentiated)77 Gastric cancer (adenocarcinoma, intestinal type)78 Bladder cancer (urothelial carcinoma)79 |

| Non-epithelial | Malignant mesothelioma (sarcomatous)80 Malignant melanoma81 Neuroblastoma82 Ewing's sarcoma83 |

|

| Hematopoietic | Hodgkin's lymphoma84 Follicular lymphoma85 |

For a localized tumor a few millimeters in size to grow larger, intratumoral angiogenesis must occur. Genetic analysis has revealed that TAMs produce VEGF, interleukin (IL)-8 (CXCL8), basic fibroblast growth factor, thymidine phosphorylase, MMP, and other molecules that are involved in angiogenesis, indicating that TAMs promote the formation of intratumoral blood vessels. Furthermore, TAMs produce immunosuppressive factors, including prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, and IL-10, and thus contribute to the immunosuppressed state of cancer patients.5–7 In fact, in studies using human tissue samples, the number of intratumoral TAM infiltration is positively correlated with formation of blood vessels and the number of regulatory T cells. Tumor-associated macrophage-derived PGE2, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, and IL-10 play important roles for induction of regulatory T cells and TAM-derived CCL17, CCL18, CCL22 are chemotactic factors for regulatory T cells.5–7 These results indicate that TAMs create environments conducive to tumor progression through their effect on angiogenesis and immunosuppression. In addition, growth factors produced by TAMs, including basic fibroblast growth factor, hepatocyte growth factor, epidermal growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), are considered to directly promote tumor cell growth.5–7

Of further interest is the suggestion, based on the results of animal model analysis, that TAMs may play a role in forming premetastatic niches in organs to which the tumor will eventually metastasize.21–23 Specifically, tumor necrosis factor-α, VEGF, and TGF-β (VEGF and TGF-β are also produced by cancer cells), which are secreted by TAMs in cancer tissues, are believed to be transported through the bloodstream to destination organs such as the lung, where they induce macrophages to produce S100A8 and serum amyloid A3.23 Both S100A8 and serum amyloid A3 recruit macrophages and tumor cells to these organs and promote the formation of metastatic foci.24,25 Thus, TAMs are believed to not only influence their local environment, but also to impact macrophages throughout the body and contribute to disease progression.

CD163 and CD204 as markers for protumoral or M2 macrophages

The heterogeneity of macrophage functions was suggested as early as the late 1990s.26,27 Macrophage activation can be broadly divided into the following two types: classically activated macrophages (M1), which promote inflammation, and alternatively activated macrophages (M2), which inhibit inflammation.27,28 Those TAMs demonstrating enhanced expression of CD163 (hemoglobin scavenger receptor), CD204 (class A macrophage scavenger receptor), CD206 (mannose receptor, C type 1), stabilin-1, arginase-1, and accelerated production of IL-10, VEGF, PGE2, and MMP9, generally show characteristics of M2 macrophages.6–8 The proangiogenic and immunosuppressive activity in the tumor microenvironment mediated by TAMs can also be considered the result of M2 macrophage function.6–8 Because CD163 and CD204 are specifically expressed on macrophages, and antibodies to these antigens that are suitable for immunohistochemical analysis are commercially available,10,29,30 many researchers have used these molecules as markers of the M2 phenotype in both in vitro and in vivo studies. The details of the functions of these molecules remain unclear; however, a few studies have indicated that these molecules are involved either in regulating the inflammatory responses or in maintaining the protumoral functions of macrophages.31–33 The clinicopathological studies using anti-CD163 or anti-CD204 antibodies are summarized in Table2. In malignant lymphoma, glioma, and kidney cancer, higher CD163 expression on TAMs is associated with worse clinical prognosis, but no correlation exists between clinical prognosis and the number of CD204-expressing TAMs.10,34–36 In esophageal cancer, a higher number of CD204-expressing TAMs is associated with poor clinical outcome, but the number of CD163-positive TAMs is not.37 These observations suggest that CD163 and CD204 are not expressed in completely identical macrophage populations. In addition, the functional significance of CD163- or CD204-positive TAMs might be different among sites and histological types of cancer. We suggest that both CD163 and CD204 should be analyzed to evaluate the polarization of TAMs and that CD163- and/or CD204-positive TAMs are considered as “protumoral” macrophages/TAMs.

Table 2.

Correlation between CD163+ or CD204+ tumor-associated macrophages and clinical prognosis in human malignant tumors

| Tumor type | Favorable prognosis | Poor prognosis |

|---|---|---|

| Epithelial | Colorectal cancer (adenocarcinoma)86 | Kidney cancer (clear cell type)34 Liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma)87,88 Liver cancer (cholangiocellular carcinoma)89 Pancreatic cancer (invasive ductal carcinoma)90,91 Lung cancer (adenocarcinoma)92,93 Lung cancer (squamous cell carcinoma)92,94 Oral cancer (squamous cell carcinoma)95 Ovarian cancer (serous adenocarcinoma)96 Esophageal cancer (squamous cell carcinoma)37 |

| Non-epithelial | Osteosarcoma97 | Leiomyosarcoma98 Brain tumor (high-grade glioma)10,42 Malignant melanoma99,100 |

| Hematopoietic | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma101 Hodgkin's lymphoma101–104 Follicular lymphoma105 Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma35 Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma36 Multiple myeloma106 |

In a recent review, based on their location and function, Qian and Pollard38 classified TAMs into the following six types: angiogenic; immunosuppressive; invasive; metastasis-associated; perivascular; and activated macrophages. Not all of these macrophage types of TAMs show the phenotype of M2 macrophages. Tumor-associated macrophages with M1 characteristics have also been observed in animal models of glioma and human pancreatic cancer.39,40 Although the concept of “M1/M2 macrophages” is a convenient hypothesis simply dividing TAMs into two populations, we should note that TAMs contain various macrophage populations with a wide range of polarization statuses stimulated by complex signals in tumor microenvironment.

Significance of direct cell–cell interactions between TAMs and tumor cells

As shown in Figure1, TAMs and tumor cells often directly contact each other, indicating that intimate cell–cell interactions exist between them. During the initial stages of tumor progression, monocyte migration factors produced by tumor cells induce infiltration of monocytes/macrophages, as described above. The macrophages that have infiltrated the tumor are activated by tumor cell-derived molecules, including IL-6, M-CSF, PGE2, and heat shock protein-27, and differentiate into protumoral/M2 macrophages.6,20 Protumoral/M2 TAMs produce a variety of angiogenic and immunosuppressive factors, as described above, and create a microenvironment conducive to tumor progression. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) has received recent attention as an important transcription factor that mediates the interaction between TAMs and tumor cells.12 Many angiogenic and immunosuppressive factors are transcriptionally regulated by Stat3. Therefore, activation of Stat3 not only plays an important role in the differentiation of macrophages into protumoral/M2 macrophages, it is also involved in tumor cell growth, metastasis, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and the acquisition of resistance to anticancer drugs and radiation therapies.12,41 Direct coculture of tumor cells and macrophages shows that Stat3 in macrophages is activated and that various factors secreted by activated macrophages, including EGF, IL-6, and IL-10, activate Stat3 in tumor cells.18,42 Activation of the M-CSF receptor (CD115) and sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1PR1) on the cell surface is believed to contribute to the cell–cell interaction mediated by Stat3.42,43 Membrane-type M-CSF on the surface of tumor cells serves as a ligand for CD115, and sphingosine-1-phosphate derived from tumor cells serves as a ligand for S1PR1. Stimulation of these receptors activates a variety of signal transduction pathways, including that of Stat3, causing TAMs to differentiate into the protumoral/M2 phenotype.44 The activation of Stat3 through cell–cell interactions between tumor cells and macrophages contributes to the formation of the microenvironment necessary for development of primary and metastatic lesions (Fig.2).

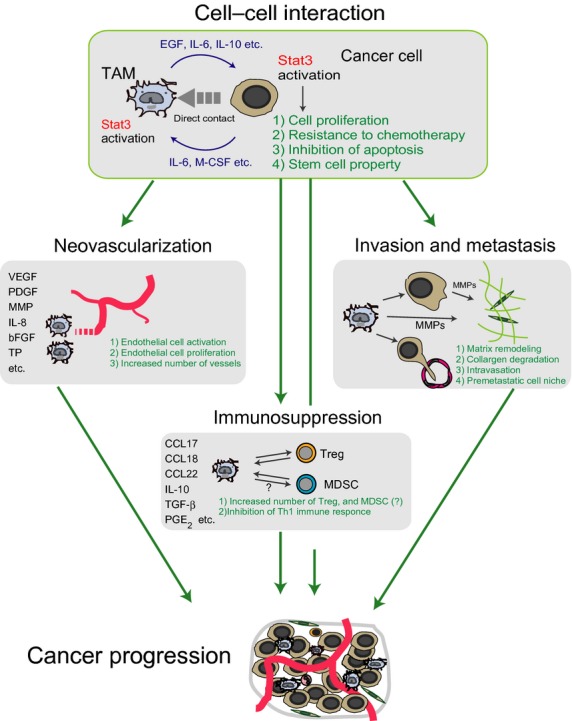

Figure 2.

Schema of the functional role of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). Tumor-associated macrophages are activated by macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), interleukin (IL)-6, and other compounds secreted by tumor cells both to induce angiogenesis by producing angiogenic factors such as VEGF and platelet-derived growth factor, and to create immunosuppressive conditions by producing immunosuppressive factors such as IL-10 and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). At the same time, growth factors that are secreted by TAMs, such as epidermal growth factor (EGF), directly promote cancer cell growth, whereas MMP and other compounds responsible for stroma remodeling promote tumor cell infiltration and metastasis. Activation of tumor cells and TAMs induced by direct cell–cell interactions may represent an extremely important event in relation to the development of malignant tumors. bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; CCL, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand; MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; Stat3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; TP, thymidine phosphorylase; Treg, regulatory T cell; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Recent studies using a murine cancer model showed that Stat3 is also an important molecule in the maintenance and anticancer drug responses of cancer stem-like cells (CSCs).45–47 The TAM-derived milk fat globule-EGF factor VIII, which is a glycoprotein belonging to an epidermal growth factor superfamily, contributes to Stat3 activation in cooperation with proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6. And Stat3 activation is preferentially associated with tumorigenesis and drug resistance in CSCs.46 In human colorectal cancer, overexpression of stem cell markers in tumor cells is reported to be associated with a high number of TAMs.48 Further studies are expected to clarify the details of the relationships between TAMs and CSCs.

Tumor-associated macrophages and myeloid-derived suppressor cells

Regarding the functional analysis of TAMs, tumor xenograft mouse or rat models are more useful than human tumors. The majority of myeloid cells infiltrating tumor tissues are immature cells in some types of murine tumors.49,50 A strong immunosuppressive response has long been known to be induced when cancer cells are transplanted into mice. In the 1980s, myeloid cells in the bone marrow of tumor-bearing mice were shown to inhibit the activation of lymphocytes.51,52 Subsequently, the same types of cells were shown to exist in the spleen, and with the advancement of analysis resulting from the identification of myeloid markers CD11b and Gr1, these cells were also shown to exist in lymph nodes and tumor tissues.51,52 Immature myeloid cells are derived from bone marrow myeloid cells and exhibit immunosuppressive activity; therefore, they are referred to as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs).51,52 Distinct from mature neutrophils and monocyte/macrophages, MDSCs have recently been divided into granulocytic MDSCs (CD11b+Ly6CintLy6Ghi), showing characteristics similar to neutrophils, and monocytic MDSCs (CD11b+Ly6ChiLy6Gneg), showing characteristics similar to monocytes/macrophages.53 Despite the observed differences among tumor histopathological types, mature macrophages (TAMs, Gr1−) and MDSCs (Gr1+) appear to coexist in the tumor tissues of mice. As MDSCs from tumor tissues differentiate into mature macrophages in ex vivo assays, MDSCs are considered to be the immature phenotype of TAMs.52,53 However, which cell type plays a greater role in angiogenesis and the activation of tumor cells remains unclear.

Systemic immunosuppression is also observed in human patients with advanced malignant tumors, suggesting the existence of cells similar in nature to the MDSCs that are found in mice. A significant increase in the number of CD14+HLA-DRlow, CD11b+CD14−CD15+, or Lin−HLA-DR−CD33+ cells is observed in the peripheral blood of patients with malignant tumors.49,53 In an ex vivo study using human blood or tumor samples of melanoma patients, MDSCs were shown to contribute more substantially to immunosuppression than TAMs.54 Given that these cell types indicate immunosuppressive activity, they may correspond to the MDSCs that are found in mice. As differences in gene expression and cell markers exist between mice and humans, sufficient care must be taken when attempting to apply the results of mouse studies to humans.

Dendritic cells in human tumor tissues

Dendritic cells (DCs) serve as other myeloid lineage cells in the tumor microenvironment, and play a critical role in integrating both innate and adaptive arms of immune responses. Myeloid DCs (mDCs) and plasmacytoid DCs constitute two major subsets of the DC population, and are distinguished from macrophages according to their unique surface marker expressions. In human DCs, mDCs are further classified as blood dendritic cell antigen (BDCA)1(CD1c)+CD11b+ and BDCA3(CD141)+ C-type lectin(CLEC)9+ populations, which are equivalent to CD11b+CD4+/− and CD8α+ or CD103+ tissue-resident mDCs, respectively.55,56 The BDCA3+ mDCs are specialized for cross-presentation of antigens from necrotic cells, whereas BDCA1+ mDCs have pleiotropic functions to prime diverse repertories of T cell subsets, in particular, dermal and mucosa-associated T cells.56–58 Human plasmacytoid DCs are characterized for their expression of BDCA2(CD303) and CD123 (IL3Rα), and produce large amounts of type-I interferon in response to viral or self-nucleic acids.54 As it is difficult to identify these molecules in paraffin-embedded pathological specimens, there are few articles describing DCs in human tumor samples. However, these phenotypic differences should help clarify the distinct functions and molecular pathways of TAMs and DCs in tumor tissues.

Targeting TAMs: a novel concept of anticancer therapy

As previously explained, TAMs promote tumor progression through induction of angiogenesis and suppression of antitumor immunity. In particular, in humans, protumoral TAMs are believed to exhibit characteristics similar to M2 macrophages, and are intimately involved in the progression of malignant tumors. As such, treatment strategies aimed at local inhibition of macrophage differentiation into the M2 phenotype are anticipated to be effective. Signal transduction pathways, including nuclear factor (NF)-κB, Stat3, Stat6, c-Myc, and interferon regulatory factor 4, are involved in differentiation into the M2 phenotype.44,59–61 Nuclear factor-κB and Stat3 are also strongly involved in tumor cell growth, and drugs targeting these molecules are currently being developed. Among such molecule-specific drugs, synergistic efficacy due to direct effects on tumor cells, as well as inhibition of the differentiation of TAMs into the M2 phenotype, is expected. Among drugs currently in use, some are active against TAMs. Cyclosporin A and trabectedin not only directly inhibit tumor cell growth, they also suppress activation of TAMs.16,62 Bisphosphonates not only suppress bone resorption by osteoclasts, they also inhibit the differentiation of TAMs into the M2 phenotype.63 The angiogenic inhibitor bevacizumab (a VEGF-inhibiting antibody) has recently been used to treat solid tumors such as colorectal adenocarcinoma, and this drug also exhibits antitumor activity by suppressing TAM migration.64,65

We developed a screening system of chemical compounds that suppress macrophage polarization toward the M2 phenotype. By screening a library of naturally occurring compounds, we have identified several compounds, including corosolic acid, that suppress M2 polarization of macrophages.66 These compounds suppress Stat3 activation and NF-κB activation both in macrophages and tumor cells in vitro.66 However, as the blocking effect of these compounds on Stat3 and NF-κB was not adequate in tumor cells, the direct effect on tumor cells was weaker than that of other anticancer drugs.66 In an in vivo study, corosolic acid appeared not to directly suppress tumor cells, but rather to stimulate the antitumor immunity of lymphocytes by inhibiting the activation of TAMs and MDSCs.67 Corosolic acid was therefore considered to show antitumor activity by means of indirect effects to myeloid cells.

Conclusion

With the recent introduction of the concept of macrophage differentiation into M1 and M2 macrophages, and clarification of the function of each of these cell types, the role of TAMs in malignant tumors is gradually emerging. Specifically, in human tumors, TAMs that have differentiated into the M2 phenotype act as “protumoral macrophages” and contribute to the progression of disease. Based on current basic research, TAMs that have differentiated into the M2 phenotype are believed to be intimately involved in angiogenesis, immunosuppression, and activation of tumor cells. Clarification of the mechanisms of TAM activation and the process of differentiation into the protumoral/M2 phenotype is anticipated to lead to new strategies for treating malignant tumors.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Funding information

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

References

- 1.Monis B, Weinberg T. Cytochemical study of esterase activity of human neoplasms and stromal macrophages. Cancer. 1961;14:369–77. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196103/04)14:2<369::aid-cncr2820140217>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Underwood JC, Carr I. The ultrastructure of the lymphoreticular cells in non-lymphoid human neoplasms. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol. 1972;12:39–50. doi: 10.1007/BF02893984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lauder I, Aherne W, Stewart J, Sainsbury R. Macrophage infiltration of breast tumours: a prospective study. J Clin Pathol. 1977;30:563–8. doi: 10.1136/jcp.30.6.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kreutz M, Fritsche J, Andreesen R. Macrophages in tumor biology. In: Burke B, Lewis CE, editors. The Macrophage. 2nd edn. Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press; 2002. pp. 458–89. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tagliabue A, Mantovani A, Kilgallen M, Herberman RB, McCoy JL. Natural cytotoxicity of mouse monocytes and macrophages. J Immunol. 1979;122:2363–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Allavena P, Sica A. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:549–55. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bingle L, Brown NJ, Lewis CE. The role of tumour-associated macrophages in tumour progression: implications for new anticancer therapies. J Pathol. 2002;196:254–65. doi: 10.1002/path.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollard JW. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:71–8. doi: 10.1038/nrc1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heusinkveld M, van der Burg SH. Identification and manipulation of tumor associated macrophages in human cancers. J Transl Med. 2011;9:216. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Komohara Y, Ohnishi K, Kuratsu J, Takeya M. Possible involvement of the M2 anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype in growth of human gliomas. J Pathol. 2008;216:15–24. doi: 10.1002/path.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sica A, Schioppa T, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumour-associated macrophages are a distinct M2 polarised population promoting tumour progression: potential targets of anti-cancer therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:717–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu H, Kortylewski M, Pardoll D. Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: role of STAT3 in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:41–51. doi: 10.1038/nri1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown CE, Vishwanath RP, Aguilar B, et al. Tumor-derived chemokine MCP-1/CCL2 is sufficient for mediating tumor tropism of adoptively transferred T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:3332–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–44. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollard JW. Macrophages define the invasive microenvironment in breast cancer. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:623–30. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1107762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabrusiewicz K, Ellert-Miklaszewska A, Lipko M, Sielska M, Frankowska M, Kaminska B. Characteristics of the alternative phenotype of microglia/macrophages and its modulation in experimental gliomas. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23902. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang J, Lu Y, Pienta KJ. Multiple roles of chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 in promoting prostate cancer growth. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:522–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernandez L, Smirnova T, Kedrin D, et al. The EGF/CSF-1 paracrine invasion loop can be triggered by heregulin beta1 and CXCL12. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3221–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kubota Y, Takubo K, Shimizu T, et al. M-CSF inhibition selectively targets pathological angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1089–102. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin EY, Nguyen AV, Russell RG, Pollard JW. Colony-stimulating factor 1 promotes progression of mammary tumors to malignancy. J Exp Med. 2001;193:727–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solinas G, Germano G, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) as major players of the cancer-related inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:1065–73. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0609385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baay M, Brouwer A, Pauwels P, Peeters M, Lardon F. Tumor cells and tumor-associated macrophages: secreted proteins as potential targets for therapy. Clin Dev Immunol. 2011;2011:565187. doi: 10.1155/2011/565187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maru Y. Logical structures extracted from metastasis experiments. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:2006–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiratsuka S, Watanabe A, Sakurai Y, et al. The S100A8-serum amyloid A3-TLR4 paracrine cascade establishes a pre-metastatic phase. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1349–55. doi: 10.1038/ncb1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiratsuka S, Watanabe A, Aburatani H, Maru Y. Tumour-mediated upregulation of chemoattractants and recruitment of myeloid cells predetermines lung metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1369–75. doi: 10.1038/ncb1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein M, Keshav S, Harris N, Gordon S. Interleukin 4 potently enhances murine macrophage mannose receptor activity: a marker of alternative immunologic macrophage activation. J Exp Med. 1992;176:287–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.1.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goerdt S, Orfanos CE. Other functions, other genes: alternative activation of antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 1999;10:137–42. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Komohara Y, Hirahara J, Horikawa T, et al. AM-3K, an anti-macrophage antibody, recognizes CD163, a molecule associated with an anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:763–71. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5A6871.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomokiyo R, Jinnouchi K, Honda M, et al. Production, characterization, and interspecies reactivities of monoclonal antibodies against human class A macrophage scavenger receptors. Atherosclerosis. 2002;161:123–32. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00624-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Komohara Y, Takemura K, Lei XF, et al. Delayed growth of EL4 lymphoma in SR-A-deficient mice is due to upregulation of nitric oxide and interferon-gamma production by tumor-associated macrophages. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:2160–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neyen C, Pluddemann A, Mukhopadhyay S, et al. Macrophage scavenger receptor a promotes tumor progression in murine models of ovarian and pancreatic cancer. J Immunol. 2013;190:3798–805. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu X, Wang XY. Antagonizing the innate pattern recognition receptor CD204 to improve dendritic cell-targeted cancer immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:770–2. doi: 10.4161/onci.19728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Komohara Y, Hasita H, Ohnishi K, et al. Macrophage infiltration and its prognostic relevance in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1424–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niino D, Komohara Y, Murayama T, et al. Ratio of M2 macrophage expression is closely associated with poor prognosis for Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) Pathol Int. 2010;60:278–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2010.02514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Komohara Y, Niino D, Saito Y, et al. Clinical significance of CD163 tumor-associated macrophages in patients with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:945–51. doi: 10.1111/cas.12167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shigeoka M, Urakawa N, Nakamura T, et al. Tumor associated macrophage expressing CD204 is associated with tumor aggressiveness of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:112–8. doi: 10.1111/cas.12188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qian BZ, Pollard JW. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell. 2010;141:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Umemura N, Saio M, Suwa T, et al. Tumor-infiltrating myeloid-derived suppressor cells are pleiotropic-inflamed monocytes/macrophages that bear M1- and M2-type characteristics. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:1136–44. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0907611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ino Y, Yamazaki-Itoh R, Shimada K, et al. Immune cell infiltration as an indicator of the immune microenvironment of pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:914–23. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Masuda M, Wakasaki T, Suzui M, Toh S, Joe AK, Weinstein IB. Stat3 orchestrates tumor development and progression: the Achilles’ heel of head and neck cancers? Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2010;10:117–26. doi: 10.2174/156800910790980197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee H, Deng J, Kujawski M, et al. STAT3-induced S1PR1 expression is crucial for persistent STAT3 activation in tumors. Nat Med. 2010;16:1421–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Komohara Y, Horlad H, Ohnishi K, et al. Importance of direct macrophage - Tumor cell interaction on progression of human glioma. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:2165–72. doi: 10.1111/cas.12015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sica A, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:787–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI59643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sherry MM, Reeves A, Wu JK, Cochran BH. STAT3 is required for proliferation and maintenance of multipotency in glioblastoma stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2383–92. doi: 10.1002/stem.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jinushi M, Chiba S, Yoshiyama H, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages regulate tumorigenicity and anticancer drug responses of cancer stem/initiating cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:12425–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106645108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bao S, Tang F, Li X, et al. Epigenetic reversion of post-implantation epiblast to pluripotent embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2009;461:1292–5. doi: 10.1038/nature08534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rao G, Wang H, Li B, et al. Reciprocal interactions between tumor-associated macrophages and CD44-positive cancer cells via osteopontin/CD44 promote tumorigenicity in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:785–97. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Greten TF, Manns MP, Korangy F. Myeloid derived suppressor cells in human diseases. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:802–7. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ueha S, Shand FH, Matsushima K. Myeloid cell population dynamics in healthy and tumor-bearing mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:783–8. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: linking inflammation and cancer. J Immunol. 2009;182:4499–506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Youn JI, Gabrilovich DI. The biology of myeloid-derived suppressor cells: the blessing and the curse of morphological and functional heterogeneity. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:2969–75. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Joyce JA, Pollard JW. Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:239–52. doi: 10.1038/nrc2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gros A, Turcotte S, Wunderlich JR, Ahmadzadeh M, Dudley ME, Rosenberg SA. Myeloid cells obtained from the blood but not from the tumor can suppress T-cell proliferation in patients with melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5212–23. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacDonald KP, Munster DJ, Clark GJ, et al. Characterization of human blood dendritic cell subsets. Blood. 2002;100:4512–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Satpathy AT, Wu X, Albring JC, Murphy KM. Re(de)fining the dendritic cell lineage. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1145–56. doi: 10.1038/ni.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jongbloed SL, Kassianos AJ, McDonald KJ, et al. Human CD141+(BDCA-3)+ dendritic cells (DCs) represent a unique myeloid DC subset that cross-presents necrotic cell antigens. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1247–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zaba LC, Fuentes-Duculan J, Steinman RM, Krueger JG, Lowes MA. Normal human dermis contains distinct populations of CD11c+BDCA-1+ dendritic cells and CD163+ FXIIIA+ macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2517–25. doi: 10.1172/JCI32282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pello OM, De Pizzol M, Mirolo M, et al. Role of c-MYC in alternative activation of human macrophages and tumor-associated macrophage biology. Blood. 2012;119:411–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-339911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Satoh T, Takeuchi O, Vandenbon A, et al. The Jmjd3-Irf4 axis regulates M2 macrophage polarization and host responses against helminth infection. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:936–44. doi: 10.1038/ni.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lawrence T, Natoli G. Transcriptional regulation of macrophage polarization: enabling diversity with identity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:750–61. doi: 10.1038/nri3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Germano G, Frapolli R, Belgiovine C, et al. Role of macrophage targeting in the antitumor activity of trabectedin. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:249–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rogers TL, Holen I. Tumour macrophages as potential targets of bisphosphonates. J Transl Med. 2011;9:177. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qian BZ, Li J, Zhang H, et al. CCL2 recruits inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis. Nature. 2011;475:222–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roland CL, Dineen SP, Lynn KD, et al. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor reduces angiogenesis and modulates immune cell infiltration of orthotopic breast cancer xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1761–71. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fujiwara Y, Komohara Y, Ikeda T, Takeya M. Corosolic acid inhibits glioblastoma cell proliferation by suppressing the activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 and nuclear factor-kappa B in tumor cells and tumor-associated macrophages. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:206–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01772.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Horlad H, Fujiwara Y, Takemura K, et al. Corosolic acid impairs tumor development and lung metastasis by inhibiting the immunosuppressive activity of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57:1046–54. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201200610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang B, Xu D, Yu X, et al. Association of intra-tumoral infiltrating macrophages and regulatory T cells is an independent prognostic factor in gastric cancer after radical resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2585–93. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1609-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ohno S, Ohno Y, Suzuki N, et al. Correlation of histological localization of tumor-associated macrophages with clinicopathological features in endometrial cancer. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:3335–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Soeda S, Nakamura N, Ozeki T, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages correlate with vascular space invasion and myometrial invasion in endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:122–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Forssell J, Oberg A, Henriksson ML, Stenling R, Jung A, Palmqvist R. High macrophage infiltration along the tumor front correlates with improved survival in colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1472–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Koide N, Nishio A, Sato T, Sugiyama A, Miyagawa S. Significance of macrophage chemoattractant protein-1 expression and macrophage infiltration in squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1667–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shimura S, Yang G, Ebara S, Wheeler TM, Frolov A, Thompson TC. Reduced infiltration of tumor-associated macrophages in human prostate cancer: association with cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5857–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhu XD, Zhang JB, Zhuang PY, et al. High expression of macrophage colony-stimulating factor in peritumoral liver tissue is associated with poor survival after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2707–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mahmoud SM, Lee AH, Paish EC, Macmillan RD, Ellis IO, Green AR. Tumour-infiltrating macrophages and clinical outcome in breast cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:159–63. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leek RD, Lewis CE, Whitehouse R, Greenall M, Clarke J, Harris AL. Association of macrophage infiltration with angiogenesis and prognosis in invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4625–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ryder M, Ghossein RA, Ricarte-Filho JC, Knauf JA, Fagin JA. Increased density of tumor-associated macrophages is associated with decreased survival in advanced thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:1069–74. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kawahara A, Hattori S, Akiba J, et al. Infiltration of thymidine phosphorylase-positive macrophages is closely associated with tumor angiogenesis and survival in intestinal type gastric cancer. Oncol Rep. 2010;24:405–15. doi: 10.3892/or_00000873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hanada T, Nakagawa M, Emoto A, Nomura T, Nasu N, Nomura Y. Prognostic value of tumor-associated macrophage count in human bladder cancer. Int J Urol. 2000;7:263–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2000.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Burt BM, Rodig SJ, Tilleman TR, Elbardissi AW, Bueno R, Sugarbaker DJ. Circulating and tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells predict survival in human pleural mesothelioma. Cancer. 2011;117:5234–44. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Makitie T, Summanen P, Tarkkanen A, Kivela T. Tumor-infiltrating macrophages (CD68(+) cells) and prognosis in malignant uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1414–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Asgharzadeh S, Salo JA, Ji L, et al. Clinical significance of tumor-associated inflammatory cells in metastatic neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3525–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.9169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fujiwara T, Fukushi J, Yamamoto S, et al. Macrophage infiltration predicts a poor prognosis for human ewing sarcoma. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:1157–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Steidl C, Lee T, Shah SP, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages and survival in classic Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:875–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Canioni D, Salles G, Mounier N, et al. High numbers of tumor-associated macrophages have an adverse prognostic value that can be circumvented by rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma enrolled onto the GELA-GOELAMS FL-2000 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:440–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.8298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nagorsen D, Voigt S, Berg E, Stein H, Thiel E, Loddenkemper C. Tumor-infiltrating macrophages and dendritic cells in human colorectal cancer: relation to local regulatory T cells, systemic T-cell response against tumor-associated antigens and survival. J Transl Med. 2007;5:62. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mano Y, Aishima S, Fujita N, et al. Tumor-associated macrophage promotes tumor progression via STAT3 signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathobiology. 2013;80:146–54. doi: 10.1159/000346196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kong LQ, Zhu XD, Xu HX, et al. The clinical significance of the CD163+ and CD68+ macrophages in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e59771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hasita H, Komohara Y, Okabe H, et al. Significance of alternatively activated macrophages in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2011;101:1913–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kurahara H, Shinchi H, Mataki Y, et al. Significance of M2-Polarized Tumor-Associated Macrophage in Pancreatic Cancer. J Surg Res. 2009;167:e211–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yoshikawa K, Mitsunaga S, Kinoshita T, et al. Impact of tumor-associated macrophages on invasive ductal carcinoma of the pancreas head. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:2012–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02411.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chung FT, Lee KY, Wang CW, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages correlate with response to epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:E227–35. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ohri CM, Shikotra A, Green RH, Waller DA, Bradding P. The tissue microlocalisation and cellular expression of CD163, VEGF, HLA-DR, iNOS, and MRP 8/14 is correlated to clinical outcome in NSCLC. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e21874. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hirayama S, Ishii G, Nagai K, et al. Prognostic impact of CD204-positive macrophages in lung squamous cell carcinoma: possible contribution of Cd204-positive macrophages to the tumor-promoting microenvironment. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1790–7. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182745968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fujii N, Shomori K, Shiomi T, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts and CD163-positive macrophages in oral squamous cell carcinoma: their clinicopathological and prognostic significance. J Oral Pathol Med. 2012;41:444–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2012.01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Reinartz S, Schumann T, Finkernagel F, et al. Mixed-polarization phenotype of ascites-associated macrophages in human ovarian carcinoma: correlation of CD163 expression, cytokine levels and early relapse. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:32–42. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Buddingh EP, Kuijjer ML, Duim RA, et al. Tumor-infiltrating macrophages are associated with metastasis suppression in high-grade osteosarcoma: a rationale for treatment with macrophage activating agents. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2110–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Espinosa I, Beck AH, Lee CH, et al. Coordinate expression of colony-stimulating factor-1 and colony-stimulating factor-1-related proteins is associated with poor prognosis in gynecological and nongynecological leiomyosarcoma. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:2347–56. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jensen TO, Schmidt H, Moller HJ, et al. Macrophage markers in serum and tumor have prognostic impact in American Joint Committee on Cancer stage I/II melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3330–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bronkhorst IH, Ly LV, Jordanova ES, et al. Detection of M2-macrophages in uveal melanoma and relation with survival. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:643–50. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wada N, Zaki MA, Hori Y, et al. Tumour-associated macrophages in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a study of the Osaka Lymphoma Study Group. Histopathology. 2012;60:313–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zaki MA, Wada N, Ikeda J, et al. Prognostic implication of types of tumor-associated macrophages in Hodgkin lymphoma. Virchows Arch. 2011;459:361–6. doi: 10.1007/s00428-011-1140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sanchez-Espiridion B, Martin-Moreno AM, Montalban C, et al. Immunohistochemical markers for tumor associated macrophages and survival in advanced classical Hodgkin's lymphoma. Haematologica. 2012;97:1080–4. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.055459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tan KL, Scott DW, Hong F, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages predict inferior outcomes in classic Hodgkin lymphoma: a correlative study from the E2496 Intergroup trial. Blood. 2012;120:3280–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-421057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Clear AJ, Lee AM, Calaminci M, et al. Increased angiogenic sprouting in poor prognosis FL is associated with elevated numbers of CD163+ macrophages within the immediate sprouting microenvironment. Blood. 2010;115:5053–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-253260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Suyani E, Sucak GT, Akyurek N, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages as a prognostic parameter in multiple myeloma. Ann Hematol. 2013;92:669–77. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1652-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]