Abstract

Although lycopene, a major carotenoid component of tomatoes, has been suggested to attenuate the risk of breast cancer, the underlying preventive mechanism remains to be determined. Moreover, it is not known whether there are any differences in lycopene activity among different subtypes of human breast cancer cells. Using ER/PR positive MCF-7, HER2-positive SK-BR-3 and triple-negative MDA-MB-468 cell lines, we investigated the cellular and molecular mechanism of the anticancer activity of lycopene. Lycopene treatment for 168 consecutive hours exhibited a time-dependent and dose-dependent anti-proliferative activity against these cell lines by arresting the cell cycle at the G0/G1 phase at physiologically achievable concentrations found in human plasma. The greatest growth inhibition was observed in MDA-MB-468 where the sub-G0/G1 apoptotic population was significantly increased, with demonstrable cleavage of PARP. Lycopene induced strong and sustained activation of the ERK1/2, with concomitant cyclin D1 suppression and p21 upregulation in these three cell lines. In triple negative cells, lycopene inhibited the phosphorylation of Akt and its downstream molecule mTOR, followed by subsequent upregulation of proapoptotic Bax without affecting anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL. Taken together, these data indicate that the predominant anticancer activity of lycopene in MDA-MB-468 cells suggests a potential role of lycopene for the prevention of triple negative breast cancer.

Keywords: Apoptosis, breast cancer, G0/G1 arrest, lycopene, triple-negative

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy among women, and the leading cause of cancer death worldwide.1 Presently, breast cancer incidence is considerably lower in Asian countries than in Western nations. However, breast cancer risk has been increasing in most Asian countries. Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease that is classified into different subtypes based on ER, PR and HER2 expression. Therapeutic options for patients with advanced breast cancer are limited and depend on the subtypes of breast cancer. Although the survival of patients with breast cancer is prolonged by molecular targeted therapy, triple-negative breast cancer, a subtype of breast cancer that is clinically negative for expression of ER/PR and HER2 protein, is associated with a poor prognosis.2 In view of the current situation where no curative therapeutic approaches exist for advanced breast cancer, the prevention of breast cancer is of extreme importance.

It is well recognized that breast cancer can largely be prevented by minimizing a variety of dietary, hormonal and lifestyle risks.3 Among a number of dietary items, fruit and vegetable intake has been shown to reduce the risk of overall breast cancer.4,5 Recent cohort studies have shown that consuming fruit and vegetables lowers the risk of ER-negative breast cancer.6,7 More recently, large pooled analyses suggest that high vegetable consumption may be associated with risk of ER-negative but not ER-positive breast cancer.8 Specifically, carotenoids included in fruit and vegetables have been suggested to account for the prevention, probably through multiple mechanisms, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative and apoptosis-inducing activities.9,10 Accordingly, carotenoid intake has been shown to be inversely associated with risk of ER-negative but not ER-positive breast cancer through a pooled analysis of 18 prospective cohort studies.11 Moreover, women with higher circulating levels of carotenoids have been shown to be at reduced risk of overall and ER-negative breast cancer.12

Lycopene is a major carotenoid detected in human plasma, present naturally in greater amounts than beta carotene and other dietary carotenoids,13 and has been suggested to exhibit potential preventive activity against several types of human cancers, such as prostate,14 lung15 and gastric cancers.16 Similarly, there are several reports suggesting that consumption of lycopene may reduce the risk of breast cancer.4,10,12 In animal studies, lycopene has been reported to reduce the development of several chemically-induced carcinogenesis in rodents, including mammary,17 colon18 and lung tumors.19 Although these preventive and anticancer activities of lycopene have been suggested to be mediated by its antioxidant capacity, which can reduce DNA damage mediated by reactive oxygen species,20 other potential anticancer mechanisms such as cell cycle arrest and/or apoptosis induction have been suggested in endometrial,21 lung,21 colon,22 prostate23,24 and mammary cancer cells.25–27 However, the inhibitory effect and possible molecular mechanisms of lycopene, including cell cycle arrest and apoptosis induction, remain poorly understood on breast cancer cells. Furthermore, lycopene, although not significantly, has been reported to reduce the risk of ER-negative breast cancer.12 Therefore, it is interesting to examine whether there are any differences in lycopene activity among different subtypes of breast cancer cells. In this study, we investigated the cellular and molecular mechanisms of the growth-inhibitory activity of lycopene against three human breast cancer cell lines that differ in their hormone receptor and HER2 status.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and chemicals

The study was performed on three subtypes of breast cancer cell lines, including hormone receptor (ER/PR) positive MCF-7, hormone receptor negative but HER2-positive SK-BR-3, and triple-negative MDA-MB-468, all purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). The origin of the cell lines and their hormone receptor and HER2 status have been described previously.28 These cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Wako, Osaka, Japan) supplemented with 10% FBS (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37°C.

All-trans-lycopene (more than 90% of purity) was purchased from Wako, and stored at −80°C. A 15-mM solution was freshly prepared with tetrahydroflan (THF) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) immediately before use for the experiments. The final concentration of THF for all experiments and treatments (including vehicle controls, where no drug was added) was maintained at <1.0%. These conditions were found to be non-cytotoxic for 168 h.

Determination of lycopene concentration in the culture medium

Lycopene was found to form a precipitate when dissolved in culture medium because of its hydrophobic property. Therefore, it was removed by centrifugation at 17 000 g for 10 min. The concentration of lycopene in the medium was measured by spectrophotometry after extraction in 2-propnol and n-hexane-dichloromethane, as described previously.29 The residue was redissolved in 500 μL methanol : THF (90:10 v/v) and 50 μL solution was injected into the reverse-phase HPLC system (ACQUITY UPLC, Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The flow rate was 0.4 mL/min and lycopene was detected at 452 nm. Lycopene was quantified by reference to standard curves. The determined concentration of lycopene thus obtained in 100 μM solution was 4.47 μM.

Determination of growth inhibition and apoptosis assessment by PARP cleavage

The anti-proliferative effect of lycopene on these breast cancer cells was assessed by WST assay, as described previously.30 Briefly, 100 μL suspension of cells was seeded into each well of a 96-well plate (BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) at a density of 2000 cells per well. This inoculation density was determined by the growth curves so that non-treated cells did not reach confluency for up to 7 days, without medium change. After overnight incubation, 100 μL lycopene solutions at various concentrations were added and cells were further cultured up to 168 h. At various times after treatment, cell viability was measured using the Premix CCK-8 Cell Proliferation Assay System (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan). The relative number of viable cells was determined by comparing the absorbance of the treated cells with the corresponding absorbance of vehicle-treated cells taken as 100%. Each experiment was performed using six replicate wells for each lycopene concentration and was carried out independently three times. The IC50 value was defined as the concentration needed for a 50% reduction. Apoptosis was assessed by PARP cleavage detected by western blot using PARP antibody. PARP is a substrate for certain caspases activated during the early stages of apoptosis. These proteases cleave PARP to fragments of approximately 89 and 24 kD. Detection of the 89-kD PARP fragment with anti-PARP thus serves as an early marker of apoptosis.

Cell cycle analysis and apoptosis measurement

At various times following treatment with lycopene, floating and trypsinized adherent cells were combined, fixed in 70% ethanol and stored at 4°C prior to cell cycle analysis. After the removal of ethanol by centrifugation, cells were then washed with PBS and stained with a solution containing RNase A and propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell cycle analyses were performed on a Beckman Coulter Gallios Flow Cytometer using the Kaluza version 1.2 software packages (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA), and the extent of apoptosis was determined by measuring the sub-G0/G1 population.

Immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis of signaling proteins for cell cycle, growth and apoptosis

Immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis were performed as described previously.30 Equal amounts of proteins or immunoprecipitated target proteins were resolved by 4–15% SDS–PAGE (Bio Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and electrotransferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Non-specific binding sites were blocked by incubating the membranes in blocking buffer (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) at room temperature for 30 min. The membranes were then incubated with primary antibodies against either phospho-mTOR (Ser2448) (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), phospho-p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204), phospho-Akt (Ser473), Cyclin D1, p21 (Santa Cruz Biotech, Dallas, TX, USA), Bcl-xL or Bax. The membranes were hybridized with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Immunoblots were developed with the enhanced chemiluminescence system (GE Healthcare) and were then quantitated using LAS-3000 Luminescent Image Analyzer (Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan). The blots were striped and reprobed with primary antibodies against mTOR, MAPK, Akt and β-actin. All primary and secondary antibodies except those for p21 and phospho-mTOR were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). For reblotting, membranes were incubated in stripping buffer (Thermo, Rockford, IL, USA) for 30 min at room temperature before washing, blocking and incubating with antibody. Triplicate determinations were made in separate experiments.

Statistical analysis

To determine the significance of observed differences, the anova was applied to the data using statistical software (version 12.0.1 for Windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The mean values were compared using Dunnett's t-test. A P-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Effects of lycopene on proliferation and survival of different subtypes of breast cancer cells

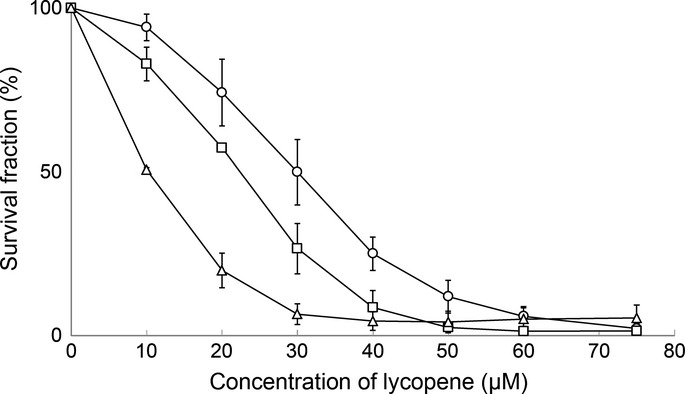

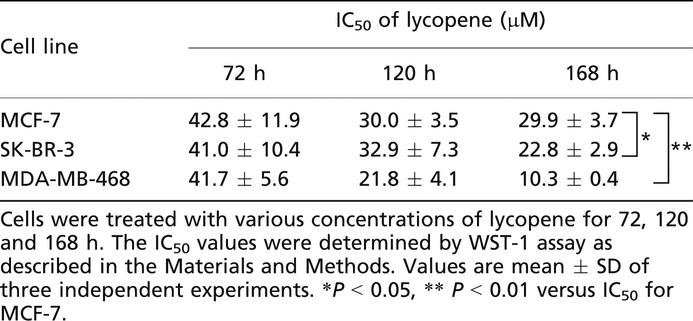

Lycopene treatment for 168 consecutive hours exhibited dose-dependent growth inhibitory activities against MCF-7, SK-BR-3 and MDA-MB-468 cells, with the greatest growth inhibition observed in MDA-MB-468 (Fig.1). MDA-MB-468 cells treated with lycopene for 168 h showed significantly lower IC50 value (10.3 μM), compared to MCF-7 cells (29.9 μM) and SK-BR-3 (22.8 μM), being threefold more sensitive to lycopene than MCF-7 cells (Table1). HER2-positive cells were moderately sensitive to lycopene, showing the IC50 between those of triple-negative and hormone-receptor positive cells. When the exposure time was shortened, IC50 values increased and there were no significant differences of lycopene sensitivity between these cell lines at 72-h exposure (Table1). These data indicate that a relatively long time (more than 72 h) would be required for lycopene to exhibit its true anti-proliferative activity for individual cell lines.

Figure 1.

Survival curves for lycopene against MCF-7 (○), SK-BR-3 (□) and MDA-MB-468 (△) cells. Cells were treated with various concentrations of lycopene for 168 h and assessed for viability by WST-1 assay, as described in the Materials and Methods. The data represent the means from three independent experiments. Bars, standard deviation.

Table 1.

IC50 values of lycopene treated for different time periods

|

Effect of lycopene on cell cycle progression and apoptosis

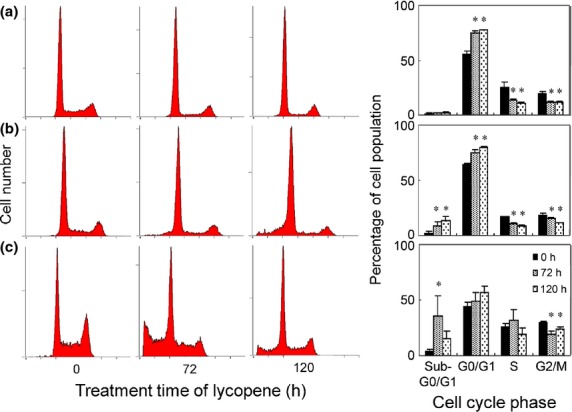

To examine whether the inhibitory effects observed in cytotoxicity assays reflect the arrest or delay of cell cycle or apoptotic cell death, cells were treated with lycopene at a dose of 50 μM, and the cell cycle progression and apoptosis were evaluated by FACS analysis. Consecutive treatment of lycopene significantly increased the proportion of cells in a G0/G1 phase after 72 h treatment, with a corresponding decrease in cells in S and G2/M phases regardless of subtypes of breast cancer (Fig.2).Upon lycopene treatment, the percentages of the sub-G0/G1 apoptotic cell population were, although not significant, slightly increased in MCF-7 cells (Fig.2a), while they were significantly increased up to 13.8% at 120 h in SK-BR-3 cells (Fig.2b). By contrast, when MDA-MB-468 cells were treated with lycopene, the sub-G0/G1 apoptotic cell population drastically increased up to 35.6% after 72 h exposure, with a decline of the sub-G0/G1 population afterwards (Fig.2c). The observed decrease in apoptotic cell populations after 120-h exposure would be due to early onset of apoptosis followed by further cleavages of DNA fragments that might not be detected by flow cytometry, because the sub-G0/G1 apoptotic cell population was substantially increased to 17.5, 28.5 and 39.4% at 24, 48 and 72 h exposure, respectively (data not shown). Therefore, it appears that lycopene-induced growth decline for MDA-MB-468 cells would be mediated by the G0/G1 arrest of the cell cycle as well as apoptosis induction.

Figure 2.

Time-course analysis of the effect lycopene on cell-cycle progression and apoptosis determined by flow cytometry. Representative cell-cycle distributions after exposure to 50 μM lycopene for 0, 72 and 120 h. MCF-7 (a), SK-BR-3 (b) and MBA-MB-468 (c). Percentages of the total cell population in the different phases of cell cycle are also shown as column bars in the right panels of each cell line. Mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *Significant difference versus vehicle control. P < 0.05.

Effects of lycopene on PARP cleavage and activations of signaling molecules for cell proliferation and survival

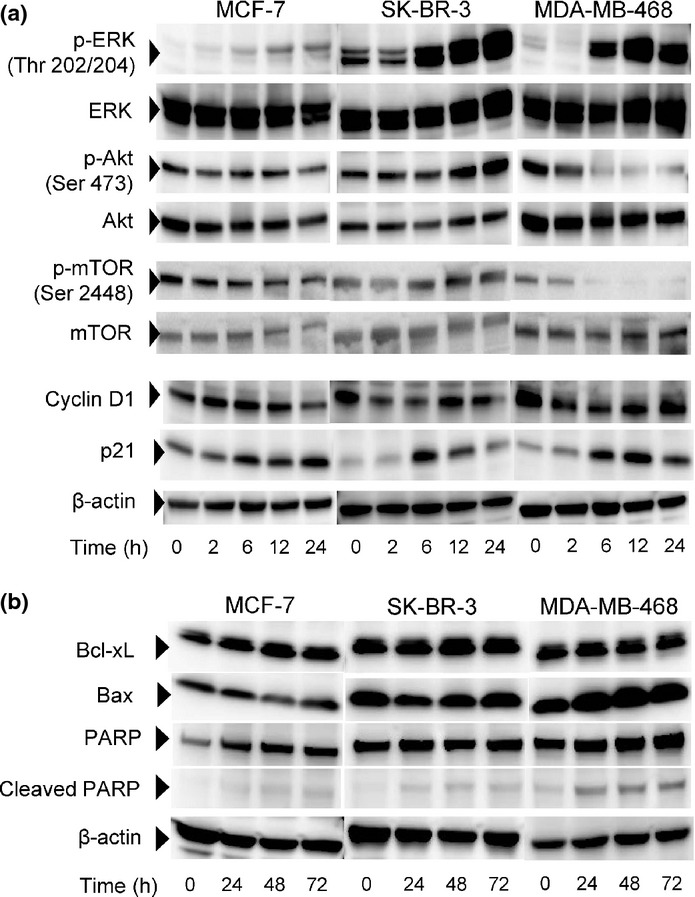

Cleavage of PARP was demonstrated from 24 to 72 h after initiation of the treatment in all three cell lines treated with lycopene (Fig.3b). The densities of western blot for PARP cleavage in MCF-7 and SK-BR-3 cells appeared less than those of MDA-MB-468 cells, supporting lower incidence of lycopene-induced apoptosis in MCF-7 and SK-BR-3 cells. Because activations of signaling molecules such as ERK1/2, Akt and mTOR have been considered as major factors contributing toward proliferation and survival, we examined the effects of lycopene on expression or activation (phosphorylation) of these proteins in these three breast cancer cell lines. Upon treatment with lycopene, the constitutive activity of ERK1/2 was enhanced 6 h after initiation of treatment in these three cell lines, and remained at high levels over 24 h (Fig.3a). By contrast, the phosphorylation of Akt and its downstream molecule mTOR was only inhibited time-dependently in MDA-MB-468 cells but not in MCF-7 and SK-BR-3 cells (Fig.3a). Cyclin D1 functioning as a key regulator of G0/G1 cell cycle checkpoint was inhibited with subsequent increase of p21 protein in all cell lines, indicating that lycopene arrests the cell cycle at G0/G1 through decrease in cyclin D1 expression and concomitant upregulation of p21 regardless of the subtypes of breast cancer.

Figure 3.

Effects of lycopene on activations of signaling molecules for cell proliferation and survival. Cells were treated with 100 μM lycopene for indicated times and harvested for western blot analysis. (a) Western blots are shown for phosphorylated and total ERK1/2, Akt, and mTOR. Cyclin D1 and p21 are also shown. (b) Effects of lycopene on the apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins, including Bax and Bcl-xL. β-Actin, PARP and cleaved PARP are shown.

Effects of lycopene on expression of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins

To clarify the apoptotic mechanism induced by lycopene, we examined the expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL as well as pro-apoptotic Bax (Fig.3b). Upon treatment with 100 μM lycopene, expression of Bcl-xL did not change in all cell lines. Expression of pro-apoptotic Bax protein did not change with the incubation time with lycopene in MCF-7 cells and SK-BR-3 cells, but was enhanced in MDA-MB-468 cells. Therefore, enhanced expression of Bax would be responsible for the lycopene-induced apoptotic induction in MDA-MB-468 cells. Both Bcl-xL and Bax appear not to be involved in lycopene-induced apoptosis in MCF-7 and SK-BR-3 cells, providing an explanation for the lower levels of apoptosis induction in these cells than in MDA-MB-468 cells.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the growth-inhibitory activity of lycopene against three human breast cancer cell lines that differ in their hormone receptor and HER2 status. Upon treatment with lycopene, a time-dependent and dose-dependent growth-inhibitory activity was observed, with the greatest inhibition observed in triple-negative MDA-MB-468 cells, when cells were treated for 168 consecutive hours, indicating that a relatively long incubation time is required to exhibit the actual cytotoxic activity for individual cell lines. This is probably because of the cytostatic nature of lycopene that requires a substantial time for the alterations of mRNA or protein to exhibit the ultimate cellular death. Accordingly, the sub-G0/G1 apoptotic fraction became noticeable after lycopene exposure for 72 h (Fig.2) despite that changes in protein expression level occurred after 6 or 24 h of exposure (Fig.3). Moreover, the dissociation was observed between the initiation of the apoptotic event and true cytotoxicity. In this experiment, WST assay was used, which measures the level of succinate dehydrogenase activity in the cytoplasm, while the apoptotic events were measured by the fluorescent intensity, which reflects nuclear size. Because it is conceivable that the cells with small nuclear size (apoptotic cells) may still contain a certain level of succinate dehydrogenase activity, these differential methods of determination may produce the time lag between apoptotic events and cytotoxicity, especially when the compounds show cytostatic but not cytocidal activity.

Because the actual concentration of lycopene in 100 μM lycopene medium was found to be 4.47 μM, the calculated IC50 values were 1.3 μM for MCF-7, 1.0 μM for SK-BR-3 and 0.5 μM for MDA-MB-468, indicating similar IC50 values of lycopene reported in a variety of human cancer cells.21,23–27 The estimated IC50 value shown here for MDA-MB-468 cells is physiologically achievable concentrations of lycopene, because median lycopene levels are frequently found in this range in human plasma.31 This suggests that regular intake of lycopene may result in plasma levels of lycopene likely to affect the growth of triple-negative breast cancer cells. Such a physiologically attainable concentration of lycopene has been reported to induce apoptosis in prostate cancer cells,24 and several clinical studies have been conducted with some clinical benefit.32–34 Therefore, clinical evaluation of lycopene is warranted in patients with breast cancer. Moreover, in animal studies, lycopene has been reported to reduce the development of 7,12-dimethyl-benz[a]anthracene-induced rat mammary tumors.17 These studies, together with the presented data, suggest both preventive and therapeutic activities of lycopene against human breast cancer. To ascertain the preventive role of lycopene, we are currently conducting an animal study using an ethyl methanesulphonate-induced rat mammary tumor model, as described in a chemoprevention study with genistein.35

In epidemiological studies dietary lycopene has been suggested to exhibit potential preventive and anticancer activity against breast cancer. Lycopene has been shown to reduce the risk of overall breast cancer more prominently than other carotenoids and to reduce, although not significantly, the risk of ER-negative but not ER-positive breast cancer.12 We have also found that HER2-positive/ER-negative SK-BR-3 cells are moderately sensitive to lycopene. Therefore, our results support the hypothesis that lycopene is potentially useful as a preventive phytochemical for overall and, more specifically, ER-negative breast cancer, including HER2-positive and triple-negative breast cancer. In ER positive cancer, the estrogen level is likely the most important factor and may, therefore, override the preventive effect of lycopene. However, the concentration of estradiol was found to be negligible in the culture medium containing 10% FBS (data not shown). Therefore, additional research is needed to identify the potential mechanisms accounting for the lower sensitivity of lycopene to hormone receptor positive cells.

Cell cycle checkpoints are important control mechanisms that ensure the proper execution of cell cycle events. Previous studies report that lycopene induces a G0/G1 cell cycle arrest, corroborated by the downregulation of cyclin D1 and/or upregulation of p27 in human colon,22 prostate23 and hormone-dependent mammary cancer cells.25 In the present study, lycopene increased the cell population in G0/G1 phase to a similar extent for these three cell lines regardless of hormone receptor and HER2 status, and reduced the expression of cyclin D1, which functions as a key regulator of the G0/G1 cell cycle checkpoint, with subsequent increase of p21 protein. These data indicate that lycopene arrests the cell cycle at G0/G1 through a decrease in cyclin D1 expression and p21 upregulation. A similar result has been reported of lycopene inducing cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase through reduction of the cyclin D1 level and retention of p27 in hormone-dependent MCF-7 and T-47D human breast cancer cell lines when cells were synchronized under serum starvation and restimulated with serum addition.25 Our results, together with the previous findings, suggest that the arrest of cell cycle at G0/G1 through downregulation of cyclin D1 and/or upregulation of p21/p27 might be a universal event triggered by lycopene treatment occurring regardless of hormone receptor or HER2 status.

The molecular mechanism whereby lycopene arrests the cells in the G0/G1 phase remains unclear. However, enhancement of constitutive activity of ERK1/2 may cause lycopene-induced G0/G1 block. ERK1/2 is an important subfamily of MAPK that control a broad range of cellular activities and physiological processes. Activation of ERK1/2 generally has proliferative capacity, but under certain conditions, ERK1/2 has been shown to have anti-proliferative activity through G1 cell cycle arrest.36 A robust early phase of ERK1/2 signaling followed by a moderate sustained phase leads to transient induction of p21 and accumulation of cyclin D1, allowing G1 progression. However, robust and prolonged activation of ERK1/2 causes G1 arrest due to long-term p21 induction and Cdk2 inhibition.36 In the present study, continuous treatment with lycopene enhanced the constitutive activity of ERK1/2 from 6 h, which remained at high levels with p21 induction over 24 h in these three cell lines. Therefore, lycopene-induced strong and sustained activation of the ERK pathway may cause a G0/G1 cell cycle blockade in breast cancer cells regardless of hormone receptor or HER2 status.

We have found for the first time that the growth inhibitory activity of lycopene is mediated by differential mechanisms of action, depending on hormone receptor and HER2 status. The apoptosis induction was markedly evident in triple-negative cell rather than hormone receptor and HER2 positive cells. In triple-negative cells, phosphorylation of Akt and downstream mTOR were clearly inhibited by lycopene, but not in hormone receptor and HER2 positive cells where apoptosis induction by lycopene is not detected or extremely low. Akt plays a critical role in controlling survival and apoptosis by directly phosphorylating mTOR,37 thereby inducing signals leading to anti-apoptotic pathways. Therefore, these data suggest that lycopene may execute its apoptotic effect primarily through blocking Akt/mTOR-mediated signaling pathways in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Moreover, lycopene did not affect the expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL in all cell lines, while expression of pro-apoptotic Bax protein was enhanced only in triple-negative cells. These data suggest that upregulation of Bax would be responsible for the lycopene-induced apoptotic induction in triple-negative cells. Lycopene-induced apoptosis has been reported in prostate and colon cancer cell lines via suppression of the Akt signaling pathway.22–24 Recently, lycopene has been reported to induce apoptosis in LNCaP prostate cancer cells by decreasing phosphorylation of Akt and increasing the Bax:Bcl-2 ratio.38 Therefore, the present study is the first report showing the role of Bax as a potential cause of lycopene-induced apoptosis through downregulation of the phosphorylation of Akt and its downstream molecule mTOR in triple-negative breast cancer.

Although the observations were obtained on a single representative cell line derived from three subtypes of human breast cancer, our data strongly suggest that the predominant anticancer activity of lycopene against triple-negative breast cancer cells could be brought not only by an arrest of cell cycle progression at the G0/G1 phase, but by apoptosis induction presumably through activation of Bax, thereby supporting the epidemiological evidence that suggests a potential role of lycopene in the prevention of this subtype of breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research C (24501020), the Strategic Research Foundation Grant-aided Project for Private Universities 2010–2012 (S1002011) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan, and the Science Research Promotion Fund from the Promotion and Mutual Aid Corporation for Private Schools of Japan.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Funding information

Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research C (24501020). Strategic Research Foundation Grant-aided Project for Private Universities 2010–2012 (S1002011) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan. Science Research Promotion Fund from the Promotion and Mutual Aid Corporation for Private Schools of Japan.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hudis CA, Gianni L. Triple-negative breast cancer: an unmet medical need. Oncologist. 2011;16(Suppl. 1):1–11. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-S1-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomson CA. Diet and breast cancer: understanding risks and benefits. Nutr Clin Pract. 2012;27:636–50. doi: 10.1177/0884533612454302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aune D, Chan DS, Vieira AR, et al. Fruits, vegetables and breast cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134:479–93. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masala G, Assedi M, Bendinelli B, et al. Fruit and vegetables consumption and breast cancer risk: the EPIC Italy study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132:1127–36. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1939-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fung TT, Hu FB, McCullough ML, et al. Diet quality is associated with the risk of estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer in postmenopausal women. J Nutr. 2006;136:466–72. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.2.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsen A, Tjonneland A, Thomsen BL, et al. Fruits and vegetables intake differentially affects estrogen receptor negative and positive breast cancer incidence rates. J Nutr. 2003;133:2342–7. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.7.2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung S, Spiegelman D, Baglietto L, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of breast cancer by hormone receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:219–36. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao AV, Rao LG. Carotenoids and human health. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55:207–16. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka T, Shnimizu M, Moriwaki H. Cancer chemoprevention by carotenoids. Molecules. 2012;17:3202–42. doi: 10.3390/molecules17033202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Spiegelman D, Baglietto L, et al. Carotenoid intakes and risk of breast cancer defined by estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor status: a pooled analysis of 18 prospective cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:713–25. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.014415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eliassen AH, Hendrickson SJ, Brinton LA, et al. Circulating carotenoids and risk of breast cancer: pooled analysis of eight prospective studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1905–16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerster H. The potential role of lycopene for human health. J Am Coll Nutr. 1997;16:109–26. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1997.10718661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei MY, Giovannucci EL. Lycopene, tomato products, and prostate cancer incidence: a review and reassessment in the PSA screening era. J Oncol. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/271063. 271063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arab L, Steck-Scott S, Fleishauer AT. Lycopene and the lung. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2002;227:894–9. doi: 10.1177/153537020222701009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu C, Russell RM. Nutrition and gastric cancer risk: an update. Nutr Rev. 2008;66:237–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharoni Y, Giron E, Rise M, Levy J. Effects of lycopene-enriched tomato oleoresin on 7,12-dimethyl-benz[a]anthracene-induced rat mammary tumors. Cancer Detect Prev. 1997;21:118–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narisawa T, Fukaura Y, Hasebe M, et al. Prevention of N-methylnitrosourea-induced colon carcinogenesis in F344 rats by lycopene and tomato juice rich in lycopene. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1998;89:1003–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1998.tb00488.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim DJ, Takasuka N, Kim JM, et al. Chemoprevention by lycopene of mouse lung neoplasia after combined initiation treatment with DEN, MNU and DMH. Cancer Lett. 1997;120:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelkel M, Schumacher M, Dicato M, Diederich M. Antioxidant and anti-proliferative properties of lycopene. Free Radic Res. 2011;45:925–40. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2011.564168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy J, Bosin E, Feldman B, et al. Lycopene is a more potent inhibitor of human cancer cell proliferation than either alpha-carotene or beta-carotene. Nutr Cancer. 1995;24:257–66. doi: 10.1080/01635589509514415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang FY, Shih CJ, Cheng LH, Ho HJ, Chen HJ. Lycopene inhibits growth of human colon cancer cells via suppression of the Akt signaling pathway. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52:646–54. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ivanov NI, Cowell SP, Brown P, et al. Lycopene differentially induces quiescence and apoptosis in androgen-responsive and -independent prostate cancer cell lines. Clin Nutr. 2007;26:252–63. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hantz HL, Young LF, Martin KR. Physiologically attainable concentrations of lycopene induce mitochondrial apoptosis in LNCaP human prostate cancer cells. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2005;230:171–9. doi: 10.1177/153537020523000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nahum A, Hirsch K, Danilenko M, et al. Lycopene inhibition of cell cycle progression in breast and endometrial cancer cells is associated with reduction in cyclin D levels and retention of p27(Kip1) in the cyclin E-cdk2 complexes. Oncogene. 2001;20:3428–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karas M, Amir H, Fishman D, et al. Lycopene interferes with cell cycle progression and insulin-like growth factor I signaling in mammary cancer cells. Nutr Cancer. 2000;36:101–11. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC3601_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teodoro AJ, Oliveira FL, Martins NB, et al. Effect of lycopene on cell viability and cell cycle progression in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Cell Int. 2012;12:36. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-12-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neve RM, Chin K, Fridlyand J, et al. A collection of breast cancer cell lines for the study of functionally distinct cancer subtypes. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:515–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stahl W, Sundquist AR, Hanusch M, Schwarz W, Sies H. Separation of beta-carotene and lycopene geometrical isomers in biological samples. Clin Chem. 1993;39:810–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ono M, Higuchi T, Takeshima M, Chen C, Nakano S. Differential anti-tumor activities of curcumin against Ras- and Src-activated human adenocarcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;436:186–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayne ST, Cartmel B, Silva F, et al. Plasma lycopene concentrations in humans are determined by lycopene intake, plasma cholesterol concentrations and selected demographic factors. J Nutr. 1999;129:849–54. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.4.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ansari MS, Gupta NP. Lycopene: a novel drug therapy in hormone refractory metastatic prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2004;22:415–20. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jatoi A, Burch P, Hillman D, et al. A tomato-based, lycopene-containing intervention for androgen-independent prostate cancer: results of a Phase II study from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group. Urology. 2007;69:289–94. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vaishampayan U, Hussain M, Banerjee M, et al. Lycopene and soy isoflavones in the treatment of prostate cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2007;59:1–7. doi: 10.1080/01635580701413934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ono M, Koga T, Ueo H, Nakano S. Effects of dietary genistein on hormone-dependent rat mammary carcinogenesis induced by ethyl methanesulphonate. Nutr Cancer. 2012;64:1204–10. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2012.718035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meloche S, Pouyssegur J. The ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway as a master regulator of the G1- to S-phase transition. Oncogene. 2007;26:3227–39. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang S, Houghton PJ. Targeting mTOR signaling for cancer therapy. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3:371–7. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(03)00071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palozza P, Colangelo M, Simone R, et al. Lycopene induces cell growth inhibition by altering mevalonate pathway and Ras signaling in cancer cell lines. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1813–21. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]