Abstract

Sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) are centrally important to health. However, there have been significant shortcomings in implementing SRHR to date. In the context of health systems reform and universal health coverage/care (UHC), this paper explores the following questions. What do these changes in health systems thinking mean for SRHR and gender equity in health in the context of renewed calls for increased investments in the health of women and girls? Can SRHR be integrated usefully into the call for UHC, and if so how? Can health systems reforms address the continuing sexual and reproductive ill health and violations of sexual and reproductive rights (SRR)? Conversely, can the attention to individual human rights that is intrinsic to the SRHR agenda and its continuing concerns about equality, quality and accountability provide impetus for strengthening the health system? The paper argues that achieving equity on the UHC path will require a combination of system improvements and services that benefit all, together with special attention to those whose needs are great and who are likely to fall behind in the politics of choice and voice (i.e., progressive universalism paying particular attention to gender inequalities).

Keywords: sexual and reproductive health and rights, universal health coverage/care, quality of care, accountability, equity

Introduction

Sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) are centrally important to health outcomes in all countries. Sex and reproduction define unique and specific health needs for girls and women over the entire life course. Whether, how and to what extent these health needs are met by the health system depends on the extent to which girls' and women's human rights are respected, protected and fulfilled. Throughout the life course, the sexual and reproductive rights (SRR) of girls and women – to bodily autonomy and integrity, to choice in relation to sexuality and reproduction, to freedom from coercion, discrimination and violence or fear of violence, to safety, satisfaction and pleasure – profoundly shape their physical and mental health and well-being.

Yet despite a growing body of evidence, and multiple intergovernmental agreements at the regional and global levels, there have been significant shortcomings in implementing SRHR to date (Fonn & Ravindran, 2011; UNFPA, 2010). Research points to the presence of large rich–poor disparities (Santhya & Jejeebhoy, 2014; Snow, Laski, & Mutumba, 2014) as well as pervasive human rights violations and social factors (Santhya & Jejeebhoy, 2014; Kismödi, Cottingham, Gruskin, & Miller, 2014) that put girls and women at a disadvantage in effectively accessing sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services and claiming their rights. This paper examines the role of the health system in these persistent deficits in equality, quality of care and accountability (E-Q-A) in SRHR (Sen, 2014). It then explores whether and how a systemic push towards universal health coverage/care (UHC) can fill these gaps, and whether a focus on SRHR can strengthen the health system itself.

Health systems have been going through significant reforms in one or more of their six building blocks identified by the WHO: service delivery, information and evidence, medical products and technologies, health workforce, health financing, and leadership and governance (WHO, 2007). These changes are, in turn, a consequence of epidemiological and demographic transitions, shifts in policy and funding environments, evolving priorities, new institutional approaches, such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM), and the entry of large private stakeholders. The transformation of the global economic environment and the impact of economic crises on national health systems have also played a role (Fonn & Ravindran, 2011; Schrecker, Labonté, & De Vogli, 2008). Concomitantly, growing recognition of the need to address continuing, and in some instances, increasing inequalities in health access and outcomes, the challenge of ‘medical poverty traps’ (Whitehead, Dahlgren, & Evans, 2001), and the growing prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), even as basic public health and management of infectious diseases remain inadequate, have given new impetus to health policies. Paradoxically, the ‘double crisis’ (Chen, 2004) of devastating disease and overwhelming health systems failure in many countries (despite some successes in addressing these; see commentary on Tangcharoensathien, Chaturachinda, & Imem, 2014) has emerged in a context of an unprecedented flow of resources for global health (IHME, 2011).

Consequently, the 1990s push for health system reforms has been partially transformed into a growing demand for UHC in which multilateral and bilateral agencies, governments and civil society are playing an important role. Normative shifts in health systems reform suggested by WHO's reaffirmation of Alma Ata (2008), the United Nations General Assembly Special Session resolution on UHC (2012) and The Commission on Information and Accountability for Women's and Children's Health (2011) are encouraging. However, they require additional resources and sustained policy follow-through (The Lancet Commission on Investing in Health, 2013) and frameworks for monitoring progress towards UHC (WHO & The World Bank, 2014).

What do these health systems reforms mean for SRHR and gender equity in health in the context of renewed calls for increased investments in the health of women and girls (Stenberg et al., 2013)? Can SRHR be integrated usefully into the call for UHC, and if so how? Can health systems reforms address the continuing sexual and reproductive ill health and violations of SRR? Conversely, can the attention to individual human rights and the particular ways in which human rights are intrinsic to the SRHR agenda, including its continuing concerns about equality, quality and accountability, provide impetus for strengthening the health system?

Our argument in this paper is two-fold. First, health system reform that does not address the core elements of the SRHR agenda will fail to meet important criteria of equality of access and affordability, or the need for acceptability and quality in health services (WHO, 2008) and can remain weak on accountability. The obverse is also true, i.e., when these core SRHR elements are addressed, there can be significant advances in E-Q-A (see commentary on Thailand; Tangcharoensathien et al., 2014).

Second, while UHC – as the successor to the health system reforms of the 1980s and 1990s – has certain powerful elements (such as its core principle of universality and its recognition of critical systemic factors), there are also important aspects that are missing or weak in the UHC framework. Most importantly, the assumption that universality will automatically result in equity on the path to UHC is not valid. We build on the work of Gwatkin and Ergo (2011) on progressive universalism to pay particular attention to gender inequalities. In this context, explicit and early attention to the unique SRH service needs of girls and women over the life course (and not only in silos such as maternity, family planning or HIV status) and their human rights can help UHC to achieve its laudable goals. The next sections of the paper expand on these points.

Impact of health system reforms on SRHR

Health policies and reforms in recent decades have been seriously constrained by reduced budgets. Increasing privatisation together with rising out-of-pocket (OOP) health expenditures by households (Travis et al., 2004; Vega, 2013; Whitehead et al., 2001; WHO, 2010b) and cost-recovery measures, specifically user fees, contributed to the medical poverty trap (Whitehead et al., 2001), leaving millions of people burdened by catastrophic health care costs (Balarajan, Selvaraj, & Subramanian, 2011; Leive, 2008). The damaging effects of this on equity in health care access, and on absolute and relative health outcomes, has led to considerable experimentation in the name of health systems reform, with mixed results (Homedes & Ugalde, 2005; Jacobs & El-Sadr, 2012; Schrecker et al., 2008).

Typically these reforms did not include core SRH services (contraception, safe abortion, maternity care, prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections including HIV, sexuality education and prevention and treatment for survivors of violence including rape; Kismödi et al., 2014; United Nations, 1994) in a consistent or integrated way, although they sometimes included silo funding for maternal health, family planning or HIV (England, 2008; Israr & Islam, 2006; UNFPA, 2012; Wilcher & Cates, 2010). Because attention to human rights was also quite alien to most of these reforms, they tended to exclude critical groups such as adolescents and their needs, to ignore deep gender inequalities in decision-making on sexuality and reproduction and the pervasiveness of violence and fear of violence among girls and women. Attention to human rights would have meant reorienting service provision as well as data gathering and monitoring systems to ‘follow’ the individual rather than the services provided, but few health reforms have taken this approach.

Standing (2002) argues that ‘Health sector reforms have largely marginalised the Cairo agenda’ (p. 25). More recent evidence gathered from a range of LMICs suggests that the earlier prognosis remains largely unchanged (Ewig, 2010; Fonn & Ravindran, 2011; Parkhurst et al., 2005), despite some investments in piecemeal SRH services provided free of charge in countries such as Nepal, Burundi and Ghana. Insufficient attention to the integrated SRHR agenda by reforms has rendered difficult the translation of the SRHR agenda into policies and programmes (Murthy & Klugman, 2004). Germain, Dixon-Mueller, and Sen (2009) showed that systematic separation, through funding and other mechanisms, of HIV/AIDS from the broader SRHR agenda served to weaken the latter even though systemic reforms towards greater accountability were pursued by the GFATM and others. Snow et al. (2014) documents persistent inequalities in access to SRHR causing harm especially to women in the lowest two wealth quintiles, with ‘key services … in shockingly short supply’. Furthermore, indirect evidence on HIV- and abortion-related and maternal deaths of adolescents suggests widespread gaps in access to health care (Chopra, Daviaud, Pattinson, Fonn, & Lawn, 2009; Houweling, Ronsmans, Campbell, & Kunst, 2007; Rashid, Akram, & Standing, 2011; Tilahun, Mengistie, Egata, & Reda, 2012). Santhya and Jejeebhoy (2014) provide evidence on the persistence of inequalities and gaps in SRHR among adolescents, especially girls.

While gender-based inequalities in access to and control over resources clearly underlie women's poor health care access, regressive health financing reforms have worked to further disempower women and limit their access to health care (Ravindran & de Pinho, 2005; WHO, 2010a). This has been especially detrimental for vulnerable groups with limited access to financial resources (i.e., adolescents, elderly, women engaged in the informal economy; Parkhurst et al., 2005; WHO, 2010a). Childbirth services (including caesarean sections) have been found unaffordable and in some instances involve catastrophic costs across a range of LMICs (Honda, Randaoharison, & Matsui, 2011; Pearson, Gandhi, Admasu, & Keyes, 2011; Titaley, Hunter, Dibley, & Heywood, 2010). This is described further in the commentary on China (Fang, 2014). In Burundi, women and children have been imprisoned and denied medical care because of inability to pay hospital fees (Kippenberg, 2006).

In instances where user fees have been removed, health care access and health outcomes have improved (De Allegri et al., 2011; United Nations, 2013; Witter, Arhinful, Kusi, & Zakariah-Akoto, 2007). However, even when financial and geographic barriers have been removed, acceptability (Govender & Penn-Kekana, 2008; Tilahun et al., 2012; Tylee, Haller, Graham, Churchill, & Sanci, 2007) and quality-of-care (Ahmed & Khan, 2011; Limwattananon, Tangcharoensathien, & Sirilak, 2011; Nguyen, Snider, Ravishankar, & Magvanjav, 2011; Ravindran & Nair, 2012) challenges can persist. SRH services, particularly those that are contested, are often the site where quality-of-care remains a challenge (Wood & Jewkes, 2006). Research from several countries indicate that women and girls suffer discrimination, violence and abuse in some health care institutions (Parkhurst et al., 2005; UNDP, WAP+, APN+, & SAARCLAW, 2013). Traditional health system reforms clearly have had very mixed impacts on women's access to SRH services, as well as on women's rights to health.

Does UHC hold out greater promise?

Integrating UHC and SRHR: the potential and the challenges

Given the growing support for UHC from major multilateral institutions such as WHO (2010b), UNICEF (Rockefeller Foundation, Save the Children, UNICEF, & WHO, 2013), bilateral donors (e.g., DFID; HM Government, 2011), a number of countries (United Nations General Assembly, 2012), and from large civil society organisations (e.g., Oxfam; Oxfam International, 2013), this section of the paper asks whether UHC could be the rising tide that lifts all boats in the health sector; and in particular, whether and how it might address the challenges posed by the deficits in SRHR.

UHC – core principles

According to the WHO (2013):

Universal coverage (UC), or universal health coverage (UHC), is defined as ensuring that all people can use the promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative health services they need, of sufficient quality to be effective, while also ensuring that the use of these services does not expose the user to financial hardship.

This definition of UC embodies three related objectives:

equity in access to health services – those who need the services should get them, not only those who can pay for them;

that the quality of health services is good enough to improve the health of those receiving services; and

financial-risk protection – ensuring that the cost of using care does not put people at risk of financial hardship.

For many who have been concerned about the limited ability of traditional health systems reform to address major health challenges, UHC's attractiveness derives from its affirmation of the right to health. This recovery of the right to health, largely lost in the dilution and evisceration of Alma Ata in recent decades, leads naturally to the principle of universality that is at UHC's core. This principle in turn is the main criterion that UHC puts forward for system reform and policies. In addition to universality, UHC's power also flows from the ease with which it is possible to incorporate key social determinants of health because it emphasises health promotion and disease prevention, particularly those relating to NCDs.

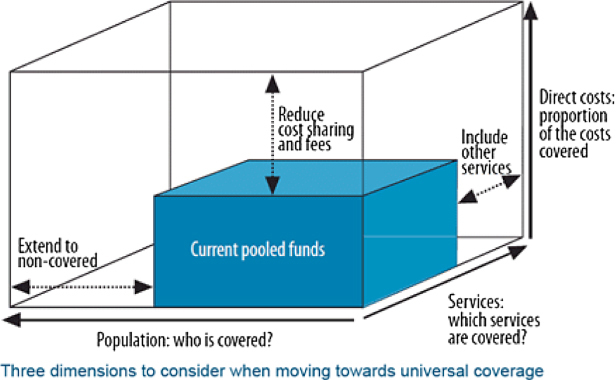

However, the criterion of equity in the WHO definition is unnecessarily limited to only the ability to pay, ignoring other bases of inequality, especially age and gender. So its criterion of quality also appears rather narrow, as there are many instances where very poor quality of care coexists with some health improvement. Nonetheless, having criteria of equity and quality as part of the WHO definition above, even in a limited form, means that a country cannot claim it is progressing towards UHC simply by moving along on one or other dimension of the UHC cube (see Figure 1 below), if at the same time inequality increases or the essential needs of key groups are excluded or unmet.

Figure 1. UHC cube WHO (2010b).

In addition to Cuba (Chisholm & Evans, 2010), a forerunner and model for UHC, in recent decades a number of LMICs, such as Brazil (2010), Sri Lanka (2010), Mexico (see commentary on Mexico; Ibáñez & Garita, 2014) and Thailand (see commentary on Thailand; Tangcharoensathien et al., 2014), are also regarded as being well on the path to universality. The combinations of public and private sector in financing and service provision, the extent of popular participation, the use of demand-side financing and the nature of regulation, inter alia, vary considerably across these countries. However, the core requirement of UHC involves increasing the coverage of people and services, making health care more accessible and affordable through interventions on the supply and demand side, while damaging OOP health expenditures decline over time (WHO, 2010b).

From the perspective of this paper, the central question is whether the core principles of UHC as spelled out above will help overcome the E-Q-A syndrome that currently bedevils health systems including SRH services? In doing so, can human rights, and in particular comprehensive SRR that are critical for women and girls, be integrated into the reform of the health system? If UHC cannot address centrally the critical needs of half the population, its claim to universality will be open to challenge.

UHC – the challenge of path dependence

We argue below that, while equity and quality are included in the WHO definition of UHC above, whether any health system purporting to move towards UHC will actually fulfil these criteria cannot be taken for granted because of the problem of path dependence. For purposes of clarity, we refer here to the most well known and widely used heuristic device for analysing UHC – the UHC cube or box (WHO, 2010b).

The inner cube represents the starting position of any country, while the outer one represents complete coverage of 100% on all three policy axes affecting who is covered, what is covered and how it is financed – people, services and financing. While serving as a useful heuristic device, it is worth noting that the cube also has limitations. For instance, the axes of population and services may not be entirely independent of each other, e.g., covering a previously uncovered population subgroup such as an indigenous group may also imply including particular services such as sickle-cell anaemia. Similarly, including adolescents should imply covering comprehensive sexuality education in the services provided.

However, the most critical issue in translating UHC's core principles into reality is path dependence. In order to meet the criteria of equity and quality spelled out in the WHO definition above, the path to achieving universality is crucially important. Which people and what services are included at which point in time governs whether the actual path will be equitable or not, and also the extent to which what gets done earlier affects what is needed later. Thus, early attention to prevention and promotion and to ensuring availability, affordability and access to quality services is likely to reduce the prevalence of late-stage NCDs or the incidence of violence against women. Improving the nutritional status of younger adolescent girls, for instance, can have a life-saving impact on them during pregnancy even years later, and on the birth-weights and survival rates of neonates (Imdad & Bhutta, 2013; Sen, Govender, & Cottingham, 2007). Both equity and quality of services depend on the path taken, which is shaped in turn by what may be called the politics of choice and voice – who is at the policy table, and what interests are effectively represented (Teerawattananon, Mugford, & Tangcharoensathien, 2007). It is important to note that UHC's major choices are almost always political and not only technical (Beyond 2015, 2012; Navarro et al., 2006), making essential the involvement and engagement of a multiplicity of stakeholders, including not only planners and technocrats but also civil society and political leaders.

Equality/equity on the path to UHC

Path dependence is also at the heart of what Victora, Vaughan, Barros, Silva, and Tomasi (2000) put forward as the inverse equity hypothesis for child health, showing that whenever an innovation appears on the scene, it is often the ‘haves’ who will benefit first and most, leading to an initial worsening of inequality of both access and outcomes. This worsening may last for quite a while before it is reversed. Although this hypothesis is not specific to UHC, it provides a salutary warning against assuming that universality will automatically translate into equitable access. A key message emerging from Gwatkin and Ergo's (2011) ongoing work on the relationship between UHC and equity in a number of countries – while suggesting mixed and ambiguous results – is that unless the actual pathway to universality has equity consciously built in, a push towards UHC may result, ironically, in greater inequity at least in its early stages. They put forward the concept of ‘progressive universalism’ as a way to address this challenge. Progressive universalism is the:

determination to ensure that people who are poor gain at least as much as those who are better off at every step of the way toward universal coverage, rather than having to wait and catch up as that goal is eventually approached. (Gwatkin & Ergo, 2011, p. 2161)

Drawing on data for a large number of LMICs, a recent World Bank review (Giedion, Alfonso, & Díaz, 2013) found that UHC did indeed improve access and often (but with less certainty) improved financial protection. However, it also concluded that careful linking of benefits to needs of target populations is essential if improved financial protection and health status are to be achieved; and that highly focused interventions can be an important early step in this direction. Several countries in Latin America and Asia have indeed, in addition to providing a universal entitlement to health services, also introduced additional financial incentives to vulnerable groups – especially women and children (Bradshaw, 2008; Lomelí, 2008; Powell-Jackson, Morrison, Tiwari, Neupane, & Costello, 2009).

Our argument in this paper is that the idea of progressive universalism should be extended to multiple dimensions. Equality/equity should be understood not only through the metric of income/wealth (i.e., economic inequality) but also through other dimensions that intersect with economic inequality but are not congruent with it, such as gender. Moreover, as Ravindran (2012) cautions, ‘gender-blind organisation and delivery of health care services may deny universal access to women even when universal coverage has been nominally achieved’. This is further illustrated in the experience from Mexico, where UHC did not easily translate into improved access to SRH services (see commentary on Mexico; Ibáñez & Garita, 2014).

This holds in general for both publicly and privately provided services, for-profit and non-profit. UHC examples include many combinations of financing and service provision by the public and private sectors. The potential for slippage between core principles and service realities in both can be serious (O'Connell, Rasanathan, & Chopra, 2013). Of particular concern for SRH services is the need to adhere to scientifically rigorous and evidence-based programming in relation to contraception, safe abortion and sexuality education in both public and private service provision since these may in some instances be opposed by religious or other health providers (Kismödi et al., 2014).

Gwatkin and Ergo's arguments and our extension suggest that achieving equity on the UHC path will require a combination of system improvements and services that benefit all, together with special attention to those whose needs are great and who are likely to fall behind in the politics of choice and voice.

The evidence suggests that two major population groups that meet these criteria are women and adolescents aged 10–19 years, especially adolescent girls (Santhya & Jejeebhoy, 2014). As suggested earlier, much of the literature on UHC and even the WHO definition above have not done well so far in recognising social determinants of inequality other than wealth/income (Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2008). It is by now well known that inequality by gender, race/ethnicity, indigeneity, caste, disability and other status intersect with each other and with income/wealth to determine who suffers the greatest deficits, whether in health, education, employment, housing or any of the Millenium Development Goals (Ewig, 2010; Limwattananon et al., 2011; Ravindran & Nair, 2012; UNFPA, 2010).

If the path to UHC is to be equitable, these multiple dimensions of inequality must be addressed in terms of both people and services. Our argument is that a focus on adolescents and women – with attention to intersecting inequalities of location, race/ethnicity/caste, disability, other status – will generate improved coverage while addressing their needs (Ravindran & Nair, 2012). To achieve equity and equality and therefore to be consistent in achieving girls' and women's SRH, UHC has to ensure, inter alia, the following:

That girls' and women's needs and concerns are not relegated to convenient but rigid silos, but are centrally included in the systemic changes that UHC promotes. An important way to do this is by ensuring that financing and other mechanisms incentivise health providers to focus on persons rather than particular diseases or health conditions. Reimbursing primary care service providers on a weighted capitation basis – where reimbursements are adjusted for need for health care services – may be necessary for prioritising service provision for vulnerable groups including women and adolescents. A combination of weighted capitation and Diagnosis-related Groups for inpatient care may be one approach (Pannarunothai, Patmasiriwat, & Srithamrongsawat, 2004).

In general, financing mechanisms must be carefully planned as they can be powerful drivers determining who gets what, when and how; and shaping whether health providers and the SRH services actually provided to girls and women ensure equality and quality.

The mixed public–private systems of the foreseeable future must be well-regulated and governed by criteria of equality, quality, scientific rigour and human rights compliance. Effective regulation of both the public and private sectors to ensure science-based, human rights compliant standards and protocols for services is essential.

Services packages must include the provision of a comprehensive and integrated set of SRH services over the life course of girls and women. This can begin with the core services spelled out earlier – contraception, safe abortion, maternity care, prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections including HIV, sexuality education and prevention and treatment for survivors of violence including rape (Garcia-Moreno & Temmerman, 2014). As the UHC system evolves, other important services (e.g., breast and reproductive cancers and infertility) should be added (see commentary on Thailand; Tangcharoensathien et al., 2014).

In order to ensure that married and unmarried adolescent girls are not excluded and that their rights are met, issues such as prevention of child, early and forced marriage, access to schooling, measures against violence and providing comprehensive sexuality education and access to SRH services with sensitivity and confidentiality need to be built in.

Data collection and effective monitoring and evaluation systems for UHC require specialised institutions to set benchmarks and monitor standards such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the UK and the National Institute of Health in Thailand. It is essential that benchmarking, standard-setting and monitoring and evaluation of SRH services be part of the mandate of such institutions in the move towards UHC.

Quality and accountability on the path to UHC

Quality of services often receives only second- or third-order attention in LMIC health policies. An important concern is that services expansion in the name of UHC might actually worsen quality of services, or cut corners on medical ethics. For instance, there is a concern about some of the consequences of the growing popularity of demand-side financing, now spreading rapidly from Latin America (Bradshaw, 2008; Lomelí, 2008) to Asia (Ahmed & Khan, 2011; Powell-Jackson et al., 2009) and Africa (Alfonso et al., 2013; Obare et al., 2013). Effective demand-side financing can significantly increase the demand for services as it did under various programmes in Latin America (Frenk, González-Pier, Gómez-Dantés, Lezana, & Knaul, 2006; Lomelí, 2008) and more recently in India under the Janani Suraksha Yojana programme (Lim et al., 2010). But a push for universality through programme silos or demand-side financing should not compromise quality or violate human rights.

Demand-side financing calls forth an increase in the quantity of services supplied. However, these need to be matched by improvements in quality of services. There is growing evidence from community groups working on the ground in a number of countries that weaknesses in the availability of beds and personnel combined with insufficient training in the face of growing demand leads to a number of questionable practices: women are discharged from the labour wards too soon after delivery; practices during delivery include routine episiotomies, application of excessive fundal pressure, unecessary oxytocin injections and other practices meant to speed up the delivery; unnecessary caesarean sections become the norm; and poorly trained personnel are unable to recognise or manage obstetric emergencies before it becomes too late to save the life of the woman (Chopra et al., 2009; Limwattananon et al., 2011; Oladapo, Daniel, & Olatunji, 2006; Rashid et al., 2011; Wahed, Moran, & Iqbal, 2010). This has led to a growing discussion in Latin America of the incidence of the phenomenon of so-called ‘obstetric violence’ as a characterisation of the serious quality failures that may result. Many of the poor-quality challenges are systemic problems, and unless there is a focus on quality assurance and ethical practice the introduction of demand-side financing could inadvertently worsen quality of care and lead to poorer health outcomes.

At the same time, the response to this cannot be to reduce the push for greater coverage. But it does mean that supply expansion must not only match projected demand increases, but also make quality assurance and ethical practice a central focus. Quality cannot remain, as it too often is, a second-order priority that receives focus only after service expansion has been consolidated – that path can result in excessive morbidity and mortality. A direct and early focus on quality through effective pre-service and in-service training, including integration of SRHR into core curricula using case-based scenarios (which have been found to be effective pedagogically), and sensitisation of all providers to all forms of inequality and to human rights is essential. This is crucial in contexts where social hierarchies intersect with each other and with economic inequality to widen the gulf between, for instance, a poor, rural dalit woman and the nurses and doctors from whom she seeks services. Building in horizontal accountability through empowered civil society organisations and social mobilisation is essential for such a focus.

A focus on individual rights not only to health (in the traditional UHC sense) but also to autonomy and bodily integrity, to decide and make choices about sexuality and reproduction provides a powerful normative fulcrum for UHC to address equality and quality as well as accountability to the underserved and subordinated.

Integrating SRR into UHC

The successful integration of SRHR into UHC is a political process and requires from its inception leadership by governments, demonstrating political will and a commitment to strengthening and institutionalising mechanisms for accountability. Realising equality/equity, quality and accountability in SRH services on the path to UHC is fundamentally a matter of respecting, protecting and fulfilling the human rights of girls and women. More attention and research are needed to identify which health system-linked variables can support and sustain human rights advances, and how they can do so.

As and when health systems begin to move towards UHC, a critical issue will be how legal reforms can be translated into real change on the ground (Kowalski, 2014). This will require focused attention to traditional and cultural practices and action that tackles how gender operates. Effective integration of SRR needs legal reforms and policies to ensure that:

The focus on individual rights is strengthened, i.e., attention is needed not just to the right to health services, but also rights to autonomy, bodily integrity and freedom of choice (i.e., SRRights, NOT just SRHealth).

The path to UHC must build in a human rights focus (Fried et al., 2014) that addresses critical elements of gender inequality – the non-recognition of girls' and women's health needs, and harmful practices and behaviours within homes, communities and in health centres that limit girls' and women's access and affordability, impacting on their health care access and outcomes.

Human resources policies including pre- and in-service education and supervision should train for and reward rights compliance, and focus on equality and quality; dis-incentivise non-compliance; and include punishing the most egregious violations. Training should also include compliance with human rights and socioeconomic equality including gender equality.

Critical in all this is effective participation by people to ensure rights compliance, redress of abuses and in monitoring and evaluation to strengthen accountability. Both vertical and horizontal accountability through effective voice and participation by women's and young people's organisations in planning, monitoring and reviewing must be built in to ensure that services are attuned to their needs, that their human rights are respected, protected and fulfilled, and equality and quality are advanced.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding Statement

This work was carried out with the aid of a grant from Canada's International Development Research Centre.

References

- Ahmed S., Khan M. M. A maternal health voucher scheme: What have we learned from the demand-side financing scheme in Bangladesh? Health Policy and Planning. 2011;(1):25–32. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso Y. N., Bishai D., Bua J., Mutebi A., Mayora C., Ekirapa-Kiracho E. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a voucher scheme combined with obstetrical quality improvements: Quasi experimental results from Uganda. Health Policy and Planning. 2013 doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balarajan Y., Selvaraj S., Subramanian S. V. Health care and equity in India. Lancet. 2011:505–515. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61894-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyond 2015 The post-2015 development agenda: What is good for health equity? 2012 http://www.worldwewant2015.org/file/300161/download/325618 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw S. From structural adjustment to social adjustment: A gendered analysis of conditional cash transfer programmes in Mexico and Nicaragua. Global Social Policy. 2008:188–207. doi: 10.1177/1468018108090638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. World Health Organization and World Bank; 2004. Harnessing the power of human resources for MDGs: High level forum on the health MDGs.http://www.hrhresourcecenter.org/node/904 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm D., Evans D. B. Improving health system efficiency as a means of moving towards universal coverage. Geneva: WHO; 2010. http://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/financing/healthreport/28UCefficiency.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra M., Daviaud E., Pattinson R., Fonn S., Lawn J. E. Saving the lives of South Africa's mothers, babies, and children: Can the health system deliver? Lancet. 2009:835–846. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health . Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: WHO; 2008. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/ Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Allegri M., Ridde V., Louis V. R., Sarker M., Tiendrebéogo J., Yé M., et al. Jahn A. Determinants of utilisation of maternal care services after the reduction of user fees: A case study from rural Burkina Faso. Health Policy. 2011:210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England R. The writing is on the wall for UNAIDS. BMJ. 2008:1072. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39569.497708.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewig C. Second-wave neoliberalism: Gender, race, and health sector reform in Peru. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press; 2010. p. p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- Fang J. China's changing health system: Implications for sexual and reproductive health. Global Public Health. 2014 doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.986171. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonn S., Ravindran T. K. S. The macroeconomic environment and sexual and reproductive health: A review of trends over the last 30 years. Reproductive Health Matters. 2011;(38):11–25. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(11)38584-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenk J., González-Pier E., Gómez-Dantés O., Lezana M. A., Knaul F. M. Comprehensive reform to improve health system performance in Mexico. Lancet. 2006:1524–1534. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69564-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried S. T., Khurshid A., Tarlton D., Webb D., Gloss S., Paz C., Stanley T. Universal health coverage: Necessary but not sufficient. Reproductive Health Matters. 2014;(42):50–60. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(13)42739-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno C., Temmerman M. Actions to end violence against women: A multi‐sector approach. Global Public Health. 2014 doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.986163. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain A., Dixon-Mueller R., Sen G. Back to basics: HIV/AIDS belongs with sexual and reproductive health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2009:840–845. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.065425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedion U., Alfonso E. A., Díaz Y. The impact of universal coverage schemes in the developing world: A review of the existing evidence. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2013. p. 151.http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2013/01/17291221/impact-universal-coverage-schemes-developing-world-review-existing-evidence UNICO Studies Series No. 25. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Govender V., Penn-Kekana L. Gender biases and discrimination: A review of health care interpersonal interactions. Global Public Health. 2008;(Suppl. 1):90–103. doi: 10.1080/17441690801892208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwatkin D. R., Ergo A. Universal health coverage: Friend or foe of health equity? Lancet. 2011:2160–2161. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HM Government . Health is global: An outcomes framework for global health 2011–15. London: Department of Health; 2011. http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications1/health-is-global.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Homedes N., Ugalde A. Why neoliberal health reforms have failed in Latin America. Health Policy. 2005;(1):83–96. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda A., Randaoharison P. G., Matsui M. Affordability of emergency obstetric and neonatal care at public hospitals in Madagascar. Reproductive Health Matters. 2011;(37):10–20. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(11)37559-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houweling T. A., Ronsmans C., Campbell O. M., Kunst A. E. Huge poor-rich inequalities in maternity care: An international comparative study of maternity and child care in developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2007:745–754. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.038588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez X. A., Garita A. Mexico: Moving from universal health coverage toward health care for all. Global Public Health. 2014 doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.986168. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IHME . Financing. global health 2011: Continued growth as MDG deadline approaches. Seattle, WA: Author; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Imdad A., Bhutta Z. A. Nutritional management of the low birth weight/preterm infant in community settings: A perspective from the developing world. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2013;(Suppl. 3):S107–S114. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israr S. M., Islam A. Good governance and sustainability: A case study from Pakistan. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2006:313–325. doi: 10.1002/hpm.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs M., El-Sadr W. M. Health systems and health equity: The challenge of the decade. Global Public Health. 2012;(Suppl. 1):S63–S72. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2012.667426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhya K., Jejeebhoy S. Sexual and reproductive health and rights of adolescent girls: Evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Global Public Health. Advance online publication. 2014 doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.986169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippenberg J. A high price to pay. Detention of poor patients in Burundian hospitals. Human Rights Watch. 2006;(8A):1–75. http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/burundi0906webwcover_1.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Kismödi E., Cottingham J., Gruskin S., Miller A. Advancing sexual health through human rights: The role of the law. Global Public Health. Advance online publication. 2014 doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.986175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski S. Universal health coverage may not be enough to ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health beyond 2014. Global Public Health. 2014:661–668. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.920892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leive A. Coping with out-of-pocket health payments: Empirical evidence from 15 African countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2008:849–856. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.049403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S. S., Dandona L., Hoisington J. A., James S. L., Hogan M. C., Gakidou E. India’s Janani Suraksha Yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities: an impact evaluation. Lancet. 2010:2009–2023. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60744-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limwattananon S., Tangcharoensathien V., Sirilak S. Trends and inequities in where women delivered their babies in 25 low-income countries: Evidence from Demographic and Health Surveys. Reproductive Health Matters. 2011;(37):75–85. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(11)37564-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomelí E. V. Conditional cash transfers as social policy in Latin America: An assessment of their contributions and limitations. Annual Review of Sociology. 2008:475–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134537. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy R. K., Klugman B. Service accountability and community participation in the context of health sector reforms in Asia: Implications for sexual and reproductive health services. Health Policy and Planning. 2004;(Suppl. 1):i78–i86. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro V., Muntaner C., Borrell C., Benach J., Quiroga Á, Rodríguez-Sanz M., et al. Pasarín M. I. Politics and health outcomes. Lancet. 2006:1033–1037. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H., Snider J., Ravishankar N., Magvanjav O. Assessing public and private sector contributions in reproductive health financing and utilization for six sub-Saharan African countries. Reproductive Health Matters. 2011;(37):62–74. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(11)37561-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obare F., Warren C., Njuki R., Abuya T., Sunday J., Askew I., Bellows B. Community-level impact of the reproductive health vouchers programme on service utilization in Kenya. Health Policy and Planning. 2013:165–175. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell T., Rasanathan K., Chopra M. What does universal health coverage mean. Lancet. 2013;(13):13–15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60955-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oladapo O. T., Daniel O. J., Olatunji A. O. Knowledge and use of the partograph among healthcare personnel at the peripheral maternity centres in Nigeria. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2006:538–541. doi: 10.1080/01443610600811243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxfam International . Universal health coverage: Why health insurance schemes are leaving the poor behind. Oxford: Oxfam GB; 2013. Oxfam Briefing Paper No. 176; p. p. 10.http://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/bp176-universal-health-coverage-091013-en_.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Pannarunothai S., Patmasiriwat D., Srithamrongsawat S. Universal health coverage in Thailand: Ideas for reform and policy struggling. Health Policy. 2004;(1):17–30. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(03)00024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhurst J. O., Penn-Kekana L., Blaauw D., Balabanova D., Danishevski K., Rahman S. A., et al. Ssengooba F. Health systems factors influencing maternal health services: A four-country comparison. Health Policy. 2005;(2):127–138. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson L., Gandhi M., Admasu K., Keyes E. B. User fees and maternity services in Ethiopia. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2011:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell-Jackson T., Morrison J., Tiwari S., Neupane B. D., Costello A. M. The experiences of districts in implementing a national incentive programme to promote safe delivery in Nepal. BMC Health Services Research. 2009;(1):97. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid S. F., Akram O., Standing H. The sexual and reproductive health care market in Bangladesh: Where do poor women go. Reproductive Health Matters. 2011;(37):21–31. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(11)37551-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran T. K. S. Universal access: Making health systems work for women. BMC Public Health. 2012;(Suppl. 1):S4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-S1-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran S., Nair M. Gender in the HLEG report. Economic and Political Weekly. 2012;(8):70–73. http://www.epw.in/special-issues/gender-hleg-report.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran T., de Pinho H. The right reforms? Health sector reform and sexual and reproductive health. Johannesburg: Women’s Health Project, School of Public Health, University of the Witwatersrand; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rockefeller Foundation, Save the Children, UNICEF, & WHO . Universal health coverage: A commitment to close the gap. London: Rockefeller Foundation; 2013. p. p. 84.http://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/uploads/files/57e8a407-b2fc-4a68-95db-b6da680d8b1f.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Schrecker T., Labonté R., De Vogli R. Globalisation and health: The need for a global vision. Lancet. 2008:1670–1676. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61691-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen G. Sexual and reproductive health and rights in the post-2015 development agenda. Global Public Health. 2014:599–606. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.917197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen G., Govender V., Cottingham J. Maternal and neonatal health: Surviving the roller-coaster of international policy. Bangalore: MNHP Project, WHO; 2007. Occasional Paper Series, No. 5.http://www2.ids.ac.uk/ghen/resources/papers/MaternalMortality2006.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Snow R., Laski L., Mutumba M. Sexual and reproductive health: Progress and outstanding needs. Global Public Health. 2014 doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.986178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standing H. An overview of changing agendas in health sector reforms. Reproductive Health Matters. 2002;(20):19–28. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(02)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenberg K., Axelson H., Sheehan P., Anderson I., Gülmezoglu A. M., Temmerman M., et al. Bustreo F. Advancing social and economic development by investing in women’s and children’s health: A new Global Investment Framework. Lancet. 2013;(13):1–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62231-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangcharoensathien V., Chaturachinda K., Imem W. Thailand: Sexual and reproductive health before and after universal health coverage in 2002. Global Public Health. 2014 doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.986166. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teerawattananon Y., Mugford M., Tangcharoensathien V. Economic evaluation of palliative management versus peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis for end-stage renal disease: Evidence for coverage decisions in Thailand. Value in Health. 2007;(1):61–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet Commission on Investing in Health Global health 2035: A world converging within a generation. 2013 http://www.thelancet.com/commissions/global-health-2035 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Tilahun M., Mengistie B., Egata G., Reda A. A. Health workers’ attitudes toward sexual and reproductive health services for unmarried adolescents in Ethiopia. Reproductive Health. 2012;(1):19. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titaley C. R., Hunter C. L., Dibley M. J., Heywood P. Why do some women still prefer traditional birth attendants and home delivery?: A qualitative study on delivery care services in West Java Province, Indonesia. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2010;(1):43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis P., Bennett S., Haines A., Pang T., Bhutta Z., Hyder A. A., et al. Evans T. Overcoming health-systems constraints to achieve the Millenium Development Goals. Lancet. 2004:900–906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16987-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tylee A., Haller D. M., Graham T., Churchill R., Sanci L. A. Youth-friendly primary-care services: How are we doing and what more needs to be done. Lancet. 2007:1565–1573. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60371-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNDP, WAP+, APN+, & SAARCLAW . Bangkok: UNDP; 2013. Protecting the rights of key HIV-affected women and girls in health care settings: A legal scan – Regional report.http://asia-pacific.undp.org/content/rbap/en/home/library/hiv_aids/protecting-the-rights-of-key-hiv-affected-women-and-girls-in-hea/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- UNFPA . How universal is access to reproductive health? A review of the evidence. New York, NY: United Nations Population Fund; 2010. http://www.unfpa.org/public/home/publications/pid/6532 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- UNFPA . Thematic evaluation: UNFPA support to maternal health 2000–2011. New York, NY: United Nations Population Fund; 2012. http://www.unfpa.org/public/home/about/Evaluation/EBIER/TE/pid/10094 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . Cairo, Egypt: 1994. Sep-13. Programme of action of the international conference on population and development. para. 7.6, U.N. Doc. A/CONF.171/13/ Rev.1 (1995) [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme; 2013. The Millennium Development Goals report 2013.http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/reports.shtml Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Commission on Information and Accountability for Women’s and Children’s Health . Keeping promises, measuring results. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly United Nations General Assembly Resolution. Global health and foreign policy. Sixty-seventh session. A/RES/67/81. 2012 http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/LTD/N12/630/51/PDF/N1263051.pdf?OpenElement Retrieved from.

- Vega J. Universal health coverage: The post-2015 development agenda. Lancet. 2013:179–180. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora C. G., Vaughan J. P., Barros F. C., Silva A. C., Tomasi E. Explaining trends in inequities: Evidence from Brazilian child health studies. Lancet. 2000:1093–1098. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02741-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahed T., Moran A. C., Iqbal M. The perspectives of clients and unqualified allopathic practitioners on the management of delivery care in urban slums, Dhaka, Bangladesh – A mixed method study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2010;(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead M., Dahlgren G., Evans T. Equity and health sector reforms: Can low-income countries escape the medical poverty trap. Lancet. 2001:833–836. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05975-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . Everybody’s business: Strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action. Geneva: Author; 2007. http://www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/en/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . Geneva: Author; 2008. The World Health Report 2008 – Primary health care (Now more than ever.http://www.who.int/whr/2008/en/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . Gender, women and primary health care renewal. Geneva: Author; 2010. http://www.who.int/gender/documents/women_and_girls/9789241564038/en/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . Geneva: Author; 2010. The World Health Report 2010. Health systems financing: The path to universal coverage.http://www.who.int/whr/2010/en/ Retrieved from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Health financing for universal coverage: What is universal coverage? 2013 http://www.who.int/health_financing/universal_coverage_definition/en/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- WHO & The World Bank . Monitoring progress towards universal health coverage at country and global levels: Framework, measures and targets. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcher R., Cates Jr W. Reaching the underserved: Family planning for women with HIV. Studies in Family Planning. 2010;(2):125–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2010.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witter S., Arhinful D. K., Kusi A., Zakariah-Akoto S. The experience of Ghana in implementing a user fee exemption policy to provide free delivery care. Reproductive Health Matters. 2007;(30):61–71. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(07)30325-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood K., Jewkes R. Blood blockages and scolding nurses: Barriers to adolescent contraceptive use in South Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 2006;(27):109–118. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)27231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]