Abstract

Background:

Chronic autoimmune urticaria (CAU) is one of the most challenging therapeutic problems faced by a dermatologist. Recently, weekly autologous serum injections have been shown to induce a prolonged remission in this disease.

Aim:

To evaluate the efficacy of repeated autologous serum injections in patients with CAU.

Materials and Methods:

Seventy patients of CAU were prospectively analyzed for the efficacy of nine consecutive weekly autologous serum injections with a post-intervention follow-up of 12 weeks. Total urticaria severity score (TSS) was monitored at the baseline, at the end of treatment and lastly at the end of 12 weeks of follow up. Response to treatment was judged by the percentage reduction in baseline TSS at the end of treatment and again at the end of 12 weeks-follow-up.

Results:

Out of the 70 patients enrolled, 11 dropped out of the injection treatment after one or the first few doses only. Among the rest of 59 patients, only 7 patients (12%) went into a partial or complete remission and remained so over the follow-up period of 12 weeks. Forty patients (68%) did not demonstrate any significant reduction in TSS at the end of the treatment period. Rest of the 12 patients showed either a good or excellent response while on weekly injection treatment, but all of them relapsed over the follow-up period of 12 weeks.

Conclusion:

Autologous serum therapy does not seem to lead to any prolonged remission in patients of CAU.

Keywords: Autoimmune urticaria, autologous serum skin test, autologous serum therapy, chronic urticaria, treatment, urticaria

What was known?

Autologous serum therapy is an effective treatment option in chronic urticarial (CU).

Weekly injections of autologous serum lead to prolonged remission in patients with CU, which lasts even after the treatment regimen is over.

Introduction

Chronic urticaria (CU) is defined as urticaria persisting daily or almost daily for more than 6 weeks. It remains a major problem in terms of etiology, investigations and management.[1] CU includes physical urticaria, chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU), and urticarial vasculitis. Approximately, 30-40% of patients with CIU have histamine-releasing auto-antibodies directed against either the high-affinity IgE receptor, or less frequently, the Fc portion of human IgE. These patients are labeled as cases of chronic autoimmune urticaria (CAU).[2,3] Clinical studies over the last decade have established that 27-61% of CIU patients, depending on the method of antibody detection, have these circulating antibodies in their blood.[4,5,6,7] These autoantibodies are responsible for causing the activation of basophils or mast cells leading to histamine release, which is the central event in CU.

The simplest screening method to identify the group of patients with CAU is the autologous serum skin test (ASST).[8] Intra-dermal injection of autologous serum in these patients elicits an immediate-type wheal and flare response indicating the presence of a circulating histamine-releasing factor in the blood. Patients with CAU traditionally suffer from a more severe urticaria with a greater number and wider distribution of wheals, more severe pruritus, and more frequent systemic symptoms.[9] These patients also need systemic steroids more commonly than those with a negative ASST.

In a recent placebo controlled study, auto-hemotherapy (injection therapy with the patients’ own blood) was shown to have a beneficial role in CAU patients.[10] In another recently conducted trial, autologous serum therapy (AST) was also found to be fairly effective in CU, including CAU.[11] In this trial, patients with CU were given weekly intramuscular injections of autologous serum and were monitored for any improvement in the total urticaria severity score (TSS). The study reported excellent results and a prolonged remission with this treatment option in patients with CU including CAU. We conducted this prospective, open label trial of AST in patients with CAU and assessed its efficacy in reducing the TSS at the end of treatment protocol as well as over the next 3-months of follow-up.

Materials and Methods

Patients presenting to the outpatient clinic of our department with a diagnosis of CU from February 2010 to February 2011 were assessed for any underlying cause by means of a proper clinical examination and relevant investigation and those with no identifiable cause were assessed for the presence of autoantibodies by performing an ASST. Patients with a positive ASST were then asked for their consent of participating in this open-label study. Seventy such consecutive patients were recruited for this therapeutic trial after a proper approval from our institutional ethics committee. Patients’ willingness to come for weekly intramuscular injections and for regular follow-up period was given particular importance during the inclusion process. Patients with a predominantly physical urticaria, patients with other systemic illnesses requiring treatment and pediatric and pregnant patients were excluded from the study. After inclusion into the study, the patients’ demographic details were recorded and the severity of their urticaria was calculated on the basis of TSS. All patients were on antihistaminic drugs at the time of inclusion, and they were advised to continue them in the minimum possible dose. The patients were told to take an H1 antihistamine orally only if their symptoms demanded so. If the patients were on systemic steroids or immunosuppressive drugs, an attempt was made to withdraw the drugs in a gradual fashion, and then stop them completely. Such patients were included in the study after a run-in period of at least 6-weeks after complete withdrawal of these drugs.

Intervention

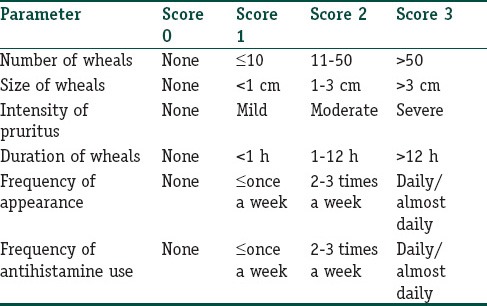

The severity of urticaria was assessed based on TSS. To calculate this score six separate parameters were taken into account as mentioned in Table 1. After calculating the baseline TSS, the patients were administered injections of autologous serum intramuscularly in the buttocks once weekly for a total of nine doses. To prepare the autologous serum, 5 ml of the venous blood was withdrawn, and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min. In this manner, 2 ml of serum was collected in a disposable syringe and was immediately injected back into the patient intramuscularly. During this treatment period of 9 weeks, antihistaminics were allowed only on a need basis. The patients were instructed to keep short-acting antihistaminic drugs at home and to consume the same when absolutely necessary. No other systemic drugs were allowed except the life-saving drugs such as antihypertensives, antidiabetics, anticonvulsants, etc., Each patient was asked about any perceivable reduction in the severity of urticaria as well as the need for antihistaminic drugs at every follow-up injection visit and the same was recorded in the response chart. At the end of the treatment period, the TSS was again calculated and the patients were instructed to come for follow-up every 2-weeks for the 1st month and then monthly for the next 2 months. Antihistaminic agents were again allowed only on a need basis. At every follow-up visit, the response to treatment was recorded and the need for antihistaminic drugs was specifically noted down. The final assessment of the patients was carried out at the last follow-up visit, i.e., 3 months after the completion of treatment protocol.

Table 1.

Calculation of total urticaria severity score

The overall response to the treatment protocol was assessed based on any reduction in the TSS from the baseline value at the end of treatment period, and at the last follow-up visit. The response to treatment was rated as excellent (76-100% reduction), good (51-75% reduction), fair (25-50% reduction), and poor (<25% reduction).

Results

Out of the total of 70 patients recruited for the study, 11 patients dropped out of the treatment schedule after one or more injections only. Thus, a total of 59 patients completed the study protocol, and were included in the final analysis of the study results.

Mean age of the patients was 34.5 ± 11 years with a range of 15-60 years. Majority of the patients were in the 3rd and 4th decades of their life.

The mean duration of urticaria in the study population was 2.8 years with a range from 3 months to 10 years.

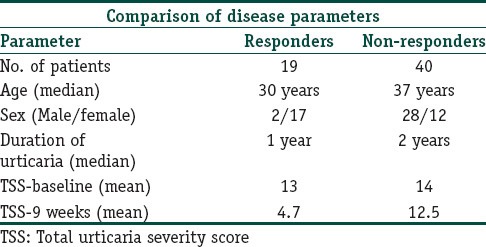

About two-thirds (40 out of 59) of our patients did not show any response to the treatment regimens with no significant change in their TSS while on treatment. Only 19 patients out of the total of 59 (32%) showed some response by way of a reduction in their TSS while they were on treatment with the weekly injections. These patients were termed as responders. Out of these 19 responders, 5 patients (9% of the study population) achieved a 75-100% reduction in TSS while on treatment, and thus were categorized as showing an excellent response. Ten other patients showed a good response (50-75% reduction) while four patients showed a fair response (25-50% reduction in TSS) at the end of the treatment regimen [Table 2].

Table 2.

Characteristics and response of study group

Both the responders as well as non-responders were followed up for the next 3 months for any relapse and any further changes in TSS. While all the non-responders continued to remain unresponsive during this follow-up period with the regular need for H1 antihistaminics, relapse was seen in 12 patients among the responder group within this period. Thus, at the end of 3-month follow-up we had only seven patients (12.5% of study population) who could be labeled as completely or partially cured with the therapeutic regimen. Among these seven patients, there were five patients who were in complete remission at the end of 12-weeks follow up (TSS of 0). These patients had attained a complete remission during the treatment regimen and then remained so over the follow-up period also. There were two more patients who showed 50-75% reduction in their TSS at the last follow-up visit as compared with the baseline.

The mean duration of urticaria in responders and non-responders was 1 and 2 years respectively [Table 2]. This difference in the duration of urticaria was found to be statistically insignificant. (P = 0.055, Mann-Whitney test). Similarly, the mean TSS at baseline did not differ between these two groups (P = 0.051, Unpaired T-test). The mean TSS recorded in responders was 12.8 ± 2.2 against 14.1 ± 2.2 in the non-responder group [Table 2].

The responders were significantly younger than the non-responders. The mean age recorded in the responder group was 28.3 ± 8.9 years in comparison with 37.5 ± 10.7 years for the non-responder group. (P = 0.002, Unpaired t-test). However, going by the overall low-percentage of patients responding to treatment, this difference does not attain much significance. Moreover, females were more commonly represented in the responder group than the males. The male-female ratio was 2:17 among responders against 28:12 among non-responders (P < 0.001, Chi-square test) [Table 2].

Discussion

Treatment of CU is most of the times quite challenging for the treating physician. This is because of the fact that the moment antihistaminics are withdrawn in these patients, they tend to develop a relapse. This makes this condition quite frustrating for the sufferer, and it is really difficult for the treating physician to make the patients understand why they should need antihistaminic so regularly in their life. To add to it, there are patients who are not able to control their symptoms by antihistaminics alone, and need systemic steroids or other immunosuppressive drugs on a regular or recurrent basis. This is more common in patients with CAU who classically have a more severe disease than patients with negative ASST.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of AST in CAU. We did not include patients with a negative ASST in our study. The reason behind this exclusion was that the biological plausibility of autologous serum as a treatment option seemed to be more in cases with a “blood-borne” or immune origin. Staubach et al. in their study on auto-hemotherapy have also found their ASST-positive patients to respond more than the ASST-negative ones.[10] We had 59 patients of CU with positive ASST who completed the study protocol. The treatment protocol was tolerated well and none of the patients reported any side effects. In our study, 32% patients (19 out of 59) showed some positive response to AST during the treatment period. This was evident in the form of a reduction in TSS in these patients. Among the 19 responders, 5 patients went into a complete remission, and their TSS scores decreased by 75-100% of their baseline values during the treatment. Rest of the responders (14 patients) the response was partial with only 25-75% reduction in TSS scores. More importantly, the therapeutic efficacy of autologous serum proved to be temporary in the majority of the responders also. This was evident in the form of a relapse of symptoms in 12 cases out of the total of 19 responders. Thus, at the end of the 3-month follow-up period, the therapeutic efficacy could be maintained only in seven patients accounting for only 12.5% of the total study population.

Our study results are not in conformity with those reported by Bajaj et al.[11] who have shown a significant percentage of their CU patients responding really well to autologous serum injection treatment. The relative lack of efficacy of AST in our patients cannot be explained easily. One of the possible reasons could be the inclusion of the only the CAU group in our study. This subgroup of patients is expected to have a relatively more severe disease than other counterparts.

AST has been reported to prevent relapse of symptoms for as long as 2 years.[11] We followed up our patients for only 12 weeks after the last autologous injection to assess the suppressive effect of treatment. However, we found 7 of our 19 responders relapsing within just 3 weeks after the end of treatment. Further follow-up of the study group showed 5 more relapses in the 2nd and 3rd month. Thus, the therapeutic response could be maintained only in 36.8% of the responders, which constituted just 12.5% of the whole study population.

In addition, we found a dramatic decline in the TSS during the first few weeks of treatment in our responder group as evident from Table 2. However, the decline in TSS could not be maintained in any of these patients in the follow up period. This is contrary to what has been reported by Bajaj et al.[11] in their study where patients showed a continuous decline in TSS during follow-up period as well.

Conclusion

Our study results indicate that AST may not be such an efficacious treatment option in patients with CAU. As we did not use a placebo arm in our study, a large placebo controlled study in a larger population group is warranted to clarify the conflicting results.

What is new?

Autologous serum therapy does not seem to offer any significant therapeutic benefit in patients with chronic urticaria.

Only a minority of patients show a temporary response to the treatment option and this positive response does not last beyond the treatment period.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.O’Donnell BF, Lawlor F, Simpson J, Morgan M, Greaves MW. The impact of chronic urticaria on the quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hide M, Francis DM, Grattan CE, Hakimi J, Kochan JP, Greaves MW. Autoantibodies against the high-affinity IgE receptor as a cause of histamine release in chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1599–604. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199306033282204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niimi N, Francis DM, Kermani F, O’Donnell BF, Hide M, Kobza-Black A, et al. Dermal mast cell activation by autoantibodies against the high affinity IgE receptor in chronic urticaria. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:1001–6. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12338544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tseng JT, Lee WR, Lin SS, Hsu CH, Yang HH, Wang KH, et al. Autologous serum skin test and autologous whole blood injections to patients swith chronic urticaria: A retrospective analysis. Dermatologica Sinica. 2009;27:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Młynek A, Maurer M, Zalewska A. Update on chronic urticaria: Focusing on mechanisms. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8:433–7. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32830f9119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, Walter Canonica G, Church MK, Giménez-Arnau AM, et al. EAACI/GA (2) LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: Management of urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1427–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vohra S, Sharma NL, Mahajan VK. Autologous serum skin test: Methodology, interpretation and clinical applications. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:545–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.55424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yadav S, Bajaj AK. Management of difficult urticaria. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:275–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.55641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Godse KV. Patch testing in chronic urticaria. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:188–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.53177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staubach P, Onnen K, Vonend A, Metz M, Siebenhaar F, Tschentscher I, et al. Autologous whole blood injections to patients with chronic urticaria and a positive autologous serum skin test: A placebo-controlled trial. Dermatology. 2006;212:150–9. doi: 10.1159/000090656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bajaj AK, Saraswat A, Upadhyay A, Damisetty R, Dhar S. Autologous serum therapy in chronic urticaria: Old wine in a new bottle. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:109–13. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.39691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]