Abstract

Lupus vulgaris (LV), is a chronic and progressive form of secondary cutaneous tuberculosis. In India, it is commonly seen over buttocks, thighs, and legs whereas involvement of nose is quite rare. Ulcerative variant particularly over nose causes destruction of cartilage, leading to irreversible deformities and contracture. High-index of suspicion is required for early diagnosis and prevention of cosmetic deformity. A case of LV over nose in a young male with ulceration is reported who responded well to anti-tubercular therapy, but left with scarring of nose, which could have been prevented if adequate awareness regarding extra-pulmonary cases would have been practiced.

Keywords: Lupus vulgaris, nose, tuberculosis

What was known?

Ulcerative lupus vulgaris can cause permanent deformities and disfigurement.

Introduction

Lupus vulgaris (LV) is the morphological variant of cutaneous tuberculosis (TB), which occurs in persons with moderate immunity and high-degree of tuberculin sensitivity.[1] Clinically, it presents with asymptomatic brownish to red solitary plaque with soft consistency, centrifugal growth and tendency to ulcerate. The plaque often shows apple jelly nodules under diascopy. It is more common in females than in males with all age group equally affected.[2]

Ulcerative type an uncommon variant of LV is characterized by scarring and deformity. In India, the common sites of involvement are buttocks, thighs, and legs.[3] Face is less commonly affected in Indians which is the common site in Europeans.[4]

We report a case of LV over nose in a young male with ulceration who responded well to anti-tubercular therapy (ATT), but left with scarring of nose.

Case Report

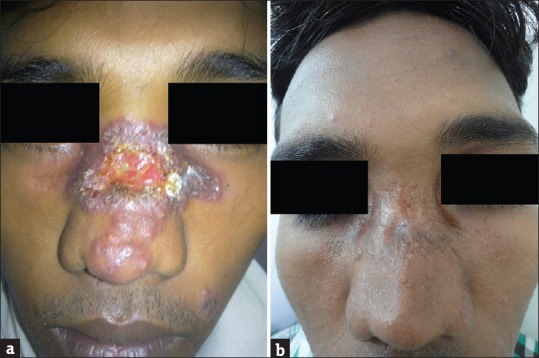

A 20-year-old male presented to skin out patient department of tertiary care center with history of (h/o) elevated lesion and ulceration over nose and adjoining parts of cheeks since 1½ year with no nasal symptoms. It started with a single papule over left cheek which gradually enlarged and progressed in due time to involve nasal bridge, extending to right side of nose. He developed swelling over right side of neck 3 months back. Patient was treated with oral and topical antibiotics by general physicians showing no improvement. Patient had h/o weight loss and decreased appetite but no h/o cough and fever. No h/o trauma at that site. No past h/o of pulmonary TB present. Patient's mother died of pulmonary TB 2 years back. General and systemic examinations were normal. Cutaneous examination showed well-defined erythematous, scaly plaque of around 8 cm × 4 cm in size, involving nasal bridge, both naso-labial folds and cheeks. Two erythematous papules were present over left cheek separately. Single ulcer of 3 cm × 3 cm in size at the center of nose, with pus and sero-sanguineous discharge was seen [Figure 1a]. Right sided submandibular and jugular nodes were enlarged and tender. Nasal septum, lips and oral mucosa were normal. Anterior rhinoscopy and nasal endoscopy findings were normal.

Figure 1.

(a) Ulcerative erythematous, scaly plaque, involving nasal bridge, both naso labial fold, with pus and sero-sanguineous discharge. (b) After 6 months of therapy, healed lesion with an atrophic scar

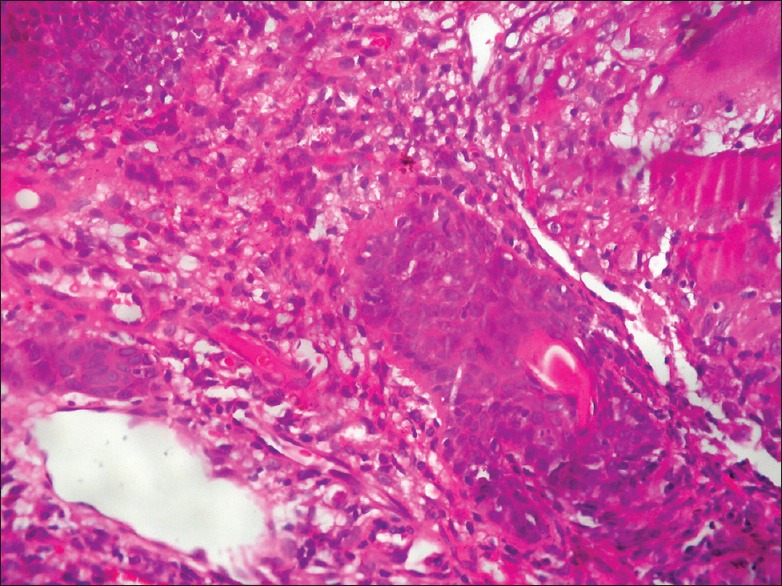

Laboratory findings were normal except erythrocyte sedimentation rate which was 60 mm/1st hour. X-ray chest was normal. Veneral disease research laboratory and ELISA for HIV were negative. Mantoux test was positive with 23 mm × 18 mm diameter induration and erythema. Ziehl-Neelsen staining didn’t reveal any acid fast bacilli. Deep biopsy taken showed features of LV on H and E, staining. Epidermal atrophy and epitheloid cell granuloma composed of langhans type of giant cells, epitheloid cells and lymphocytes along with intense inflammatory infiltrate was seen in dermis [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Epitheloid cell granuloma composed of langhans type of giant cells (H and E, ×40)

Patient was treated with category-1 ATT under revised national TB control programme. Lesions healed after 6 months of therapy but an atrophic scar was left over nose at the site of ulceration [Figure 1b].

Discussion

WHO has reported more than 90% TB cases occurring in developing countries.[5] TB poses a major health problem in India. Tubercular infection varies from pulmonary to extra-pulmonary TB. Cutaneous type accounts for 1.5% cases of extra-pulmonary TB.[6]

LV is a chronic progressive and commonest form of secondary cutaneous TB accounting for approximately 59% cases in India.[7] It is a post primary paucibacillary cutaneous TB that occurs in previously sensitized individual with moderate immunity. Usually re-infectious type is seen in Indians. It is a disease of northern climates and is rare in tropics as it needs a cool and moist climate.[8]

The source of infection can be either endogenous, exogenous or following Bacillus calmette–guérin vaccination.[9] Most often LV develop after cervical lymphadenitis or pulmonary TB.[10]

Clinically, it is characterized by brownish red papules or nodules that gradually expand by involution in one area with expansion in other and central scarring. It can present in different clinical pattern which includes papular, nodular, plaque, ulcerative, vegetative, hypertrophic, atrophic, tumor like and mutilating type.[6,11]

Ulcerative and mutilating variant of LV are characterized by scarring, ulceration, crust over areas of necrosis with destruction of deep tissue and cartilage resulting in deformity while vegetative form produces marked infiltration, ulceration, and necrosis with minimal scarring.[12]

In Europe, over 80% of lesions are on head and neck, particularly nose and cheeks[13] while in Turkey, localization of LV on face is about 62%.[14] Rich and porous venous plexus with stasis, cold hypoxia, impaired fibrinolysis and host defense at a lower temperature is the reason behind development of lesions over the nose in western countries.[15] Face, ear, and neck lesions may heal with scarring. Involvement of nose with LV is quiet uncommon in India. Very few cases of LV over nose have been reported.[4,8,10,12,15,16]

Many conditions mimics LV over nose which includes sarcoidosis (lupus pernio), tuberculoid leprosy, lupoid leishmaniasis, deep fungal infections, lymphoma, lupoid rosacea, Wegener's granulomatosis, Bowens disease, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, various types of histiocytosis and psoriasis.[17] In developing country like ours, where prevalence of TB is high it should be kept in mind as one of the differential diagnosis in lesions over nose.

LV of external nose can lead to various complications like dacrocystitis, corneal ulceration, nasopharyngeal lupus, scarring and destruction of nasal vestibule, tip and alae nasi.[8] Involvement of nose with LV often remains undiagnosed or misdiagnosed leading to scarring in ulcerative variant with destruction of cartilage leading to irreversible deformity and contracture of face.[18]

LV is a paucibacillary form of TB, so infective bacilli are rarely seen on tissue staining and culture are frequently negative in 50% cases.[11] Histopathology my reveal non-specific inflammatory changes from superficial lesions thus missing the diagnosis, so deep biopsy is required to reach up to the diagnosis.

According to WHO the recommended treatment for LV is same as pulmonary TB.[5,17]

Lack of awareness about extra-pulmonary cases leads to their delayed diagnosis and increased morbidity. TB is still an important health problem in underdeveloped and developing countries. Its incidence is rising throughout developed countries also in recent years, hence importance of having high index of suspicion is required among general physicians and dermatologist to diagnose and intervene early.

Conclusion

LV runs an extremely chronic course leading to disfigurement and mutilations. Ulcerative form is the most destructive and disfiguring form. Our patient presented with ulcerative form of LV over nose which was diagnosed on the basis of clinical history, morphology of lesions, mantoux test and was supported by histopathology. Lesions completely subsided after ATT, leaving depressed scar over nose which could have been avoided by early diagnosis.

What is new?

A deep biopsy is recommended for histopathology to rule out chances of misdiagnosis, delayed diagnosis and cosmetic morbidity as a result of Lupus vulgaris.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Singh G, Kaur V, Singh S. Bacterial Infections. IADVL Textbook of Dermatology. In: Valia RG, Valia AR, editors. 3rd ed. Mumbai: Bhalani Publishing House; 2008. pp. 241–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wozniacka A, Schwartz RA, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A, Borun M, Arkuszewska C. Lupus vulgaris: Report of two cases. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:299–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.01976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh G. Lupus vulgaris in India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1974;40:257–60. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kakakhel KU, Fritsch P. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:355–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1989.tb02478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. WHO Global tuberculosis control: A short update to the 2009, report; pp. 4–5. WHO/HTM/TB/2009. 426. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sethuraman G, Ramesh V, Ramam M, Sharma VK. Skin tuberculosis in children: Learning from India. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:285–94. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2007.11.006. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramesh V, Misra RS, Jain RK. Secondary tuberculosis of the skin. Clinical features and problems in laboratory diagnosis. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:578–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1987.tb02309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garg A, Wadhera R, Gulati SP, Singh J. Lupus vulgaris of external nose with septal perforation: A rarity in antibiotic era. Indian J Tuberc. 2010;57:157–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murugan S, Vetrichevvel T, Subramanyam S, Subramanian A. Childhood multicentric lupus vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:343–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.82510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varshney S, Gupta P, Bisti SS, Singh RK, Gupta N. Lupus vulgaris of Nose. JK Sci. 2009;11:91–3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yates VM. Mycobacterial infections. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Vol. 2. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing; 2010. pp. 31.1–31.41. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Ghoshal L. Facial swelling and ulceration with nasal destruction. Cleve Clin J Med. 2011;78:289–90. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.78a.10097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miteva L. Alopecia: A rare manifestation of lupus vulgaris. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:659–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2001.01287-6.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aliagaoglu C, Mustafa A, Umran Y, Ismail RE, Timur H. Lupus vulgaris with unusual involvement. Eur J Gen Med. 2007;4:135–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Behera B, Devi B, Patra N. Mutilating lupus vulgaris of face: An uncommon presentation. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:199–200. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.60568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Padmavathy L, Rao LL, Ethirajan N, Krishnaswami B. Ulcerative lupus vulgaris of face: An uncommon presentation in India. Indian J Tuberc. 2007;54:52–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morais P, Ferreira O, Nogueira A, Bettencourt H, Azevedo F. A nodulo-ulcerative lesion on the nose. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sehgal VN, Wagh SA. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Current concepts. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:237–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1990.tb02554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]