Abstract

Candidiasis is a common fungal infection that is prevalent in immunocompromised individuals. In this study, an oral vaccine against Candida albicans was developed by using the molecular display approach. Enolase 1 protein (Eno1p) of C. albicans was expressed on the Lactobacillus casei cell surface by using poly-gamma-glutamic acid synthetase complex A from Bacillus subtilis as an anchoring protein. The Eno1p-displaying L. casei cells were used to immunize mice, which were later challenged with a lethal dose of C. albicans. The data indicated that the vaccine elicited a strong IgG response and increased the survival rate of the vaccinated mice. Furthermore, L. casei acted as a potent adjuvant and induced high antibody titers that were comparable to those induced by strong adjuvants such as the cholera toxin. Overall, the molecular display method can be used to rapidly develop vaccines that can be conveniently administered and require minimal processing.

Keywords: Eno1p, Candida albicans, Lactococcus casei, Molecular display technology, Candidiasis

Introduction

Candidiasis is a common infection in immunocompromised individuals and is caused by the opportunistic fungal pathogen, Candida albicans or by other Candida species [1–5]. Candidiasis diagnosis is challenging due to the unavailability of rapid and efficient detection assays. Candidiasis is commonly treated by administering antifungal agents such as caspofungin, micafungin, anidulafungin, and amphotericin B [6]. However, the emergence of drug-resistant Candida strains has rendered some treatments ineffective. Therefore, the development of vaccines against candidiasis is of considerable research interest.

Previous studies have identified several candidate C. albicans proteins for vaccine development. For example, mice vaccinated with enolase 1 protein (Eno1p), a glycolytic enzyme of C. albicans encoded by the ENO1 gene, showed increased antibody titers against Eno1p and higher survival time than mice that were not vaccinated [7]. In addition to Eno1p, other C. albicans proteins such as the hyphal wall protein, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, phosphoglycerate kinase [8], and malate dehydrogenase 9 can also induce protective immune responses against candidiasis when administered with appropriate adjuvant compounds. In vaccine development studies, a convenient way to administer antigens can accelerate research.

In recent years, several molecular display approaches that use genetically engineered microorganisms to produce foreign proteins on the cell surface have been developed [10–12]. The molecular display method involves the fusion of a heterologous protein, such as an antigen, with a bacterial cell-wall protein to enable transport and anchoring of the hybrid protein to the cell surface. The molecular display method has been used to express various functional and antigenic proteins on the microbial cell surface. For example, an antigen obtained from the red sea bream iridovirus (RSIV), a fish pathogen, was displayed on the yeast cell surface to create an orally administered vaccine for cultured fish [13]. Molecular display of HPV16 E7 on Lactobacillus casei with the cell-wall anchor of the Streptococcus pyogenes M6 protein has been reported to induce cellular immunity against HPV in mice [14]. Another study used the molecular display method to express the HPV16 E7 antigen on the surface of L. casei by using poly-gamma-glutamic acid (γ-PGA) synthetase complex A (PgsA) from Bacillus subtilis as an anchoring protein [15]. The study showed that mice orally inoculated with this vaccine showed E7-specific antitumor immune responses [15]. Thus, L. casei has been previously used in oral vaccine development and is a Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) organism [16]. Furthermore, L. casei can be used for vaccine preparation without an extensive purification process as required for vaccines that use pathogenic organisms such as Escherichia coli. In addition, molecular display methods produce antigenic proteins more rapidly and conveniently than the conventional vaccine production methods.

In this study, we used a molecular display method to express a C. albicans antigen, Eno1p, on L. casei and developed a novel type of oral vaccine against candidiasis. The Eno1p from C. albicans was selected as the model antigen for display on L. casei because the vaccine effect of Eno1p has been demonstrated using a molecular display system involving Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells [17]. Delivery of the cells to mice by oral administration prolonged the survival of mice infected with lethal levels of C. albicans.

These findings indicate that the L. casei display system might provide a convenient tool to develop vaccines against candidiasis and other fungal diseases.

Results and Discussion

Construction of the Plasmid for Display of Eno1p on L. casei

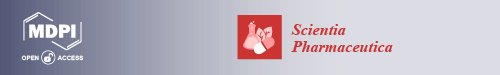

The amplification of the C. albicans Eno1 gene by PCR and using pULD1-eno1 17 as a template yielded a fragment of the expected size, which was cloned into the pKV plasmid. The insert within pKV was sequenced and compared with the appropriate sequences in the Candida genome database (http://www.candidagenome.org/). The plasmid was named pPG-eno1 (Fig. 1B) and introduced into L. casei 525 to display the antigenic protein on its surface (Fig. 1A). Poo et al. suggested that PgsA could successfully display the antigenic protein on L. casei and the cell induced a mucosal immune response [15]. Therefore, PgsA was selected as the anchoring protein for Eno1p.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the cell surface display of a protein on Lactobacillus casei and its genetic construction

(A) Molecular display of a candidate protein on the L. casei cell surface.

(B) The plasmid pPG-Eno1 for the display of a candidate protein (in this case, Eno1p) on the surface of L. casei with poly-gamma-glutamic acid (γ-PGA) synthetase complex A (PgsA) as an anchoring protein.

Preparation of Eno1p- Displaying L. casei for Oral Administration

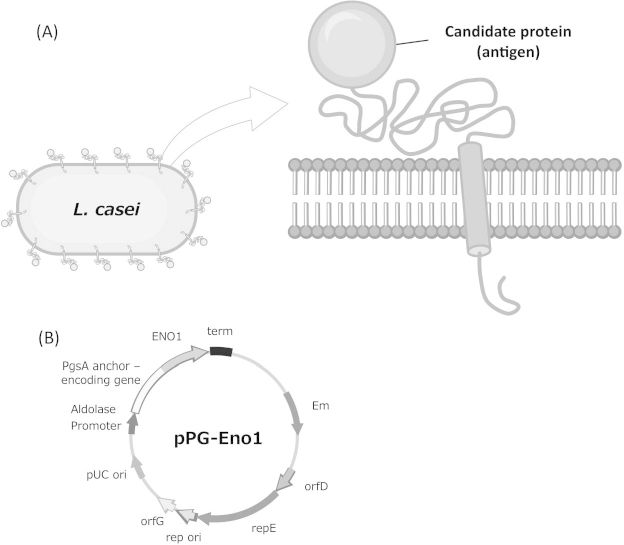

Plasmid transfection was confirmed by performing auxotrophic selection and colony direct PCR. The colony PCR yielded a 1.3-kbp fragment of the size of the ENO1 gene (Fig. 2A). The Eno1 proteins (Eno1p) were identified using western blotting. The anti-FLAG antibody detected a protein band at the molecular weight of 47 kDa, which is the expected Eno 1 protein size (Fig. 2B). Taken together, the genetic and protein analyses data indicated that Eno1p-displaying L. casei cells were successfully constructed.

Fig. 2.

Confirmation of Eno1p display

(A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR-amplified ENO1 sequence.

(B) Western blot analysis of Eno1p. Lane M: molecular weight marker; lane 1: cell surface fraction of control cell (L. casei 525); lane 2: cell surface fraction of L. casei harboring pPG-Eno1.

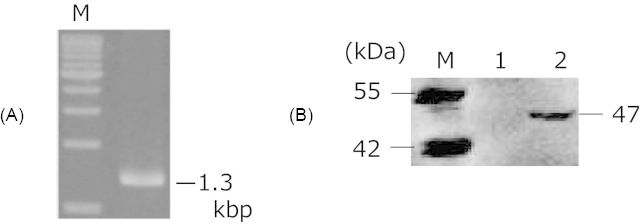

Determination of C. albicans Lethal Dose

To determine the lethal dose of C. albicans for C57BL/6 mice, various concentrations of C. albicans SC5314 cells that ranged between 1.0 × 103 to 5.0 × 105 cells were injected into the mice as described previously [18, 19]. A dosage of 2.2 × 105 cells per animal was considered as standard and doses that were lower or higher than the standard dose were assessed to determine the lethal dose (Fig. 3). The data indicated that the LD50 was 1.9 × 104 cells/mouse (Fig. 3). On the 12th day after C. albicans inoculation, the survival rate of mice that were administered 2.2 × 105 cells became 0%. Therefore, administering a C. albicans dose of 1.1 × 105 cells/mouse was thought to be enough to kill all the mice with no immunization.

Fig. 3.

C. albicans challenge test

C. albicans strain SC5314 was injected into mice and the survival rate was evaluated. Asterisk: 2.2 × 103 cells; square: 1.8 × 104 cells; circle: 8.8 × 104 cells; triangle: 2.2 × 105 cells; diamond: 2.2 × 106 cells.

Immunological Response after Administration of L. casei Cells

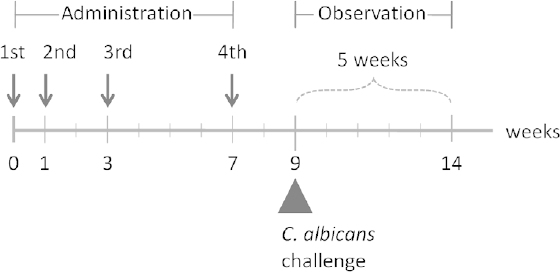

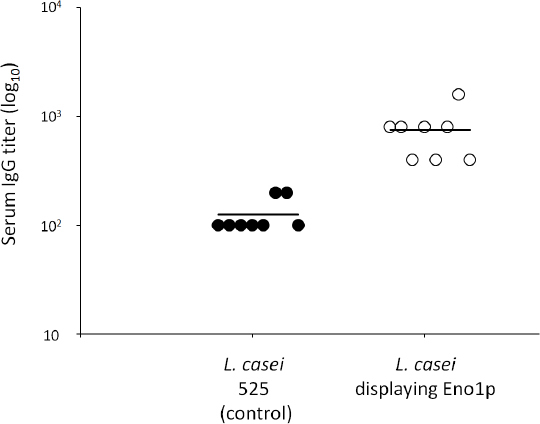

The mice were vaccinated by oral administration of the L. casei 525 cells (control) or Eno1p-displaying L. casei cells four times during the 7-week period (Fig. 4). The average anti-Eno1p antibody titer generated after oral administration of Eno1p-displaying L. casei cells was 7.5 × 102 and that of the control L. casei 525 was 1.3 × 102 (Fig. 5). In the case of Eno1p-displaying yeast [17], the antibody titer (5.2 × 103) was seven times higher than that of Eno1p-displaying L. casei. A comparison of the average antibody titers generated by L. casei and yeast indicated that yeast induced a better immunological response against Eno1p [17]. However, there was less variation in antibody titers generated by Eno1p-displaying L. casei (titer range: 1.0 × 102 to 1.6 × 103). The antibody titers generated by Eno1p-displaying yeast showed more variability (titer range: 1.0 × 102 to 5.2 × 104). Thus, the antibody immune response generated by L. casei may be advantageous for generating vaccines. In addition, L. casei cells are potent adjuvants and the control mice inoculated with L. casei cells showed a 1.3 × 102 IgG titer, which was comparable to the titer of mice inoculated with adjuvant compounds, Freund’s incomplete adjuvant, and the cholera toxin (approximately 2 × 102 IgG titer) [17]. The adjuvant characteristics of L. casei have been previously reported 20 and cell wall components such as beta-glucan have been identified as potent adjuvants in S. cerevisiae [21].

Fig. 4.

Schedule of oral administration of Eno1p-displaying L. casei

Fig. 5.

Antibody response of mice after oral administration of L. casei cells

Vaccine Efficacy of Orally Administrated Eno1p-Expressing L. casei Cells

Although the direct quantification of Eno 1p displayed on the L. casei surface could not be performed before the oral vaccination of mice, we used a previously published methodology for estimating Eno 1p in a yeast display system [17]. L. casei cell growth was measured to indirectly estimate Eno 1p expression. The data indicated that the cell growth pattern of L. casei with and without Eno1p display was similar to that of S. cerevisiae cultured in liquid medium and that both L. casei and S. cerevisiae cells progressed into the late log phase after 24 h of cultivation. Since S. cerevisiae cultivated for 24 h yielded the largest number of Eno1p molecules on the cell surface, L. casei cells grown in liquid medium for 24 h were harvested and used for the vaccination. Mice were orally administered four doses of L. casei cells over the course of a 7-week period before challenging with a lethal dose of C. albicans.

The survival rate data indicated that after the challenge with C. albicans for 25 d, 20% of the mice that received an oral administration of the Eno1p-displaying cells survived longer than the mice that received an oral administration of the control cells (Table 1). After 35 d post-challenge, 10% of the mice that received an oral administration of the Eno1p-displaying cells had survived. Although this survival rate is lower than that of the Eno1p-displaying yeast cells that showed a 60% survival rate in a previous study [17], increasing the administered dose of L. casei may enhance the induction of the immune response [22]. These results indicate that a molecular display system using L. casei and the antigenic protein Eno1p can be used to develop an effective oral vaccine against candidiasis. To enhance the survival rate by vaccination, the efficiency of the transformation of L. casei should be analyzed and improved further.

Tab. 1.

Survival rate of C. albicans-infected mice that were immunized with either control L. casei or Eno1p-displayed L. casei

| Days | L. casei 525 control cells (%) | Eno1p-displayed L. casei cells (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100 | 100 |

| 5 | 100 | 100 |

| 15 | 50 | 70 |

| 25 | 0 | 20 |

| 35 | 0 | 10 |

Conclusion

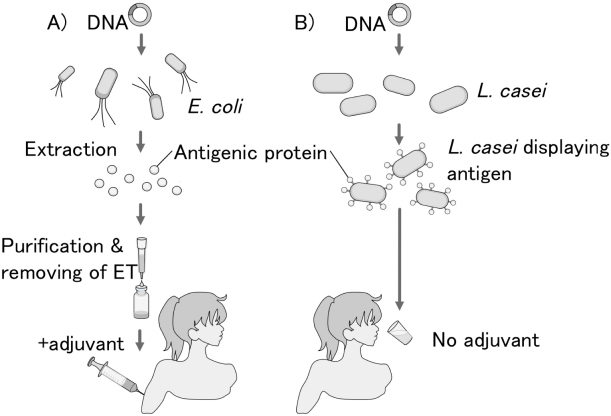

In summary, C. albicans Eno1p was successfully displayed on the surfaces of L. casei cells. Mice immunized with the Eno1p-displaying L. casei cells had enhanced survival rates after exposure to a lethal dose of C. albicans. The oral administration of the L. casei cells displaying Eno1p on their surfaces protected 20% of the mice against candidiasis. The present study demonstrates that the molecular display method can be used for expressing immunogenic proteins on bacterial cells for developing oral vaccines against candidiasis and other infectious diseases. Molecular display system–based vaccine development is rapid and simply requires the DNA sequence encoding the antigenic protein and the appropriate host cells. This vaccine does not require protein purification, which is a tedious process required for conventional vaccine development (Fig. 6). The molecular display methodology can therefore be efficiently adapted to rapidly develop vaccines against other infectious diseases and emerging pandemics. For the development of additional vaccines against candidiasis, we have used proteomic analyses to identify other candidate antigenic proteins [23, 24] and characterized various host cells that could be suitable for developing a molecular display system [25].

Fig. 6.

Schematic comparison of development and administration procedures of conventional vaccine and oral vaccine produced by the molecular display of an antigen on the microorganism’s cell surface

(A) Conventional vaccination using proteins produced by E. coli requires antigen purification and endotoxin (ET) removal.

(B) Oral vaccine produced by the molecular display system does not require intensive processing.

Experimental

Materials and Methods

Strains and Media

The E. coli strain DH5α [F− endA1 hsdR17 (rK−, mK+) supE44 thi1 recA1 gyrA96 ΔlacU169 ðφ80 lacZΔM15] was used as a host for the manipulation of recombinant DNA. The E. coli strain BL21 [F− ompT hsdSB(rB−, mB−) gal dcm (DE3)] was used to produce the antigenic protein. Both E. coli strains were grown in LB medium containing 1% (w/v) tryptone, 0.5% (w/v) yeast extract, 0.5% (w/v) sodium chloride, and 0.1% (w/v) glucose. L. casei strain 525 was cultured in MRS medium (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Plasmid Construction and Transformation of Microbial Cells

The plasmid pPG-eno1 for the display of Eno1p on the L. casei cell surface was constructed as described in this section. First, the C. albicans Eno1p-encoding plasmid pULD1-eno1 17 was propagated in E. coli. Next, the ENO1 gene was amplified by performing PCR with the following two primers:

5′-CGGGATCCATGTCTTACGCCACTAAAATCCAC-3′ and 5′-GCTCTAGATTACAATTGAGAAGCCTTTTGGAAATCTTTACC-3′

The ENO1 PCR product was inserted into pKV by using the BamH1 and Xba1 restriction sites [22]. The nucleotide sequence of this construct was assessed by using an ABI PRISM 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The constructed plasmid pPG-Eno1 was transformed into L. casei 525 by using the previously described electroporation protocol for microorganisms [26].

Colony PCR and Western Blot Analysis

To assess the transformation of L. casei with the recombinant plasmid, select colonies were used to perform PCR with primers flanking a region on the PgsA-Eno1-FLAG sequence. For western blot analysis, the bacterial cell membrane and cell wall fractions were isolated using a 10-mL culture of L. casei by following a previously described protocol [27]. The samples were resolved on a 20% polyacrylamide gel under denaturing conditions and then transferred to a 0.45-µm nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking overnight at 4°C with Blocking One (Nacalai, Kyoto, Japan), membranes were incubated at 4°C overnight with the mouse monoclonal antibody against FLAG (Sigma, MO, USA) at a dilution of 1:5000 in PBS. After washing the membranes with Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20 (washing buffer), the target proteins were detected with alkaline phosphatase (AP)-labeled ReserveAP goat anti-mouse IgG (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) at a dilution of 1:1000 with 1% PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST) as the diluent. Nitro-blue tetrazolium chloride and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3’-indolylphosphatase p-toluidine salt (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) were used as the AP colorimetric substrate for visualization.

Animals

The animal experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use committee, and animal experiments were conducted according to the institutional ethical guidelines for animal experiments. Female C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Japan SLC, Inc. (Shizuoka, Japan). Mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free manner and allowed to drink and eat ad libitum.

Immunological Challenge using C. albicans

Before the survival studies for C. albicans-infected mice were undertaken, LD50 determination studies were conducted to determine the suitable lethal dose of C. albicans required for performing the survival tests. Mice were infected with C. albicans at concentrations ranging from 2.2 × 103 cells/100 μL PBS to 2.2 × 106 cells/100 μL PBS. Mouse survival was assessed over a period of 26 days after C. albicans administration.

To assess the vaccine efficacy, mice were infected with the determined LD50 dose of C. albicans resuspended in 100 μL PBS by tail-vein injection two weeks after the last immunization. Mice were observed daily for four weeks after the C. albicans challenge.

Oral Administration Using Live L. casei Cells Displaying Eno1p on Their Surfaces

Seven-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (ten per group) were immunized with a solution of Eno1p-expressing L. casei cells or control cells (5.6 × 1011 cfu/400 µL). The immunization was administered to ten mice at weeks 0, 1, and 3 (priming) and then at week 7 (booster). The host strain L. casei 525 was used as a control. The L. casei cells were suspended in PBS (400 μL per animal) and administered via an intragastric tube after 2 h of fasting, once per day for 5 d per week. Blood samples were collected at week 9 from the tail vein to determine the titer of serum IgG.

Endpoint Titer

The indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed for antibody analysis of antisera collected at week 9. Briefly, 96-well microtiter plates (Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, NY, USA) were coated with 50 μL/well of recombinant Eno1p (0.01 μg/μL). The plates were blocked with 1% BSA dissolved in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20. Serially diluted antisera of mice, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (1:4000; Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and HRP substrate were sequentially added to the wells. After 20 min incubation at 25ºC, the reaction was stopped by adding 1 mol/L H2SO4, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm (OD450) by using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Redmond, WA, USA). The serum IgG antibody titer was defined as the serum dilution that gave an OD450 value equal to 0.1.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the regional innovation creation R&D programs of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, Japan. The L. casei display system was provided by BioLeaders Corporation.

Authors’ Statements

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Animal Rights

Animal experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use committee, and animal experiments were conducted according to the institutional ethical guidelines for animal experiments.

References

- 1.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:133–163. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00029-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naglik JR, Challacombe SJ, Hube B. Candida albicans secreted aspartyl proteinases in virulence and pathogenesis. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:400–428. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.67.3.400-428.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sobel JD, Chaim W. Vaginal microbiology of women with acute recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2497–2499. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8880507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barousse MM, Steele C, Dunlap K, Espinosa T, Boikov D, Sobel JD, Fidel PL., Jr Growth inhibition of Candida albicans by human vaginal epithelial cells. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:1489–1493. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/324532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noble SM, Johnson AD. Genetics of Candida albicans, a diploid human fungal pathogen. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41:193–211. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.genet.41.042007.170146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rautemaa R, Richardson M, Pfaller MA, Perheentupa J, Saxén H. Activity of amphotericin B, anidulafungin, caspofungin, micafungin, posaconazole, and voriconazole against Candida albicans with decreased susceptibility to fluconazole from APECED patients on longterm azole treatment of chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;62:182–185. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montagnoli C, Sandini S, Bacci A, Romani L, La Valle R. Immunogenicity and protective effect of recombinant enolase of Candida albicans in a murine model of systemic candidiasis. Med Mycol. 2004;42:319–324. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13693780310001644653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xin H, Cutler JE. Vaccine and monoclonal antibody that enhance mouse resistance to candidiasis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:1656–1667. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CVI.05215-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shibasaki S, Aoki W, Nomura T, Karasaki M, Sewaki T, Ueda M. Evaluation of Mdh1 protein as an antigenic candidate of a vaccine against candidiasis. Biocontrol Sci. 2014;19:51–55. http://dx.doi.org/10.4265/bio.19.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shibasaki S, Maeda H, Ueda M. Molecular display technology using yeast-arming technology. Anal Sci. 2009;25:41–49. http://dx.doi.org/10.2116/analsci.25.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shibasaki S, Kawabata A, Ishii J, Yagi S, Kadonosono T, Kato M, Fukuda N, Kondo A, Ueda M. Construction of a novel synergistic system for production and recovery of secreted recombinant proteins by the cell surface engineering. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;75:821–828. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00253-007-0868-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rockberg J, Löfblom J, Hjelm B, Uhlén M, Ståhl S. Epitope mapping of antibodies using bacterial surface display. Nat Methods. 2008;5:1039–1045. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamaru Y, Ohtsuka M, Kato K, Manabe S, Kuroda K, Sanada M, Ueda M. Application of the arming system for the expression of the 380R antigen from red sea bream iridovirus (RSIV) on the surface of yeast cells: a first step for the development of an oral vaccine. Biotechnol Prog. 2006;22:949–953. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/bp060130x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Cortes-Perez NG, Le Loir Y, Alcocer-González JM, Tamez-Guerra RS, de Oca-Luna RM, Langella P. An inducible surface presentation system improves cellular immunity against human papillomavirus type 16 E7 antigen in mice after nasal administration with recombinant lactococci. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:427–433. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15096553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poo H, Pyo HM, Lee TY, Yoon SW, Lee JS, Kim CJ, Sung MH, Lee SH. Oral administration of human papillomavirus type 16 E7 displayed on Lactobacillus casei induces E7-specific antitumor effects in C57/BL6 mice. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1702–1709. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijc.22035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schiraldi C, Valli V, Molinaro A, Cartenì M, De Rosa M. Exopolysaccharides production in Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Lactobacillus casei exploiting microfiltration. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;33:384–390. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10295-005-0068-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shibasaki S, Aoki W, Nomura T, Miyoshi A, Tafuku S, Sewaki T, Ueda M. An oral vaccine against candidiasis generated by a yeast molecular display system. Pathog Dis. 2013;69:262–268. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/2049-632X.12068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo G, Ibrahim AS, Spellberg B, Nobile CJ, Mitchell AP, Fu Y. Candida albicans Hyr1p confers resistance to neutrophil killing and is a potential vaccine target. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1718–1728. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/652407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Wq, Hu Xc, Zhang X, Ge Y, Zhao S, Hu Y, Ashman RB. Immunisation with the glycolytic enzyme enolase confers effective protection against Candida albicans infection in mice. Vaccine. 2011;29:5526–5533. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogawa T, Asai Y, Sakamoto H, Yasuda K. Oral immunoadjuvant activity of Lactobacillus casei subsp. casei in dextran-fed layer chickens. Br J Nutr. 2006;95:430–434. http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/BJN20051629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berner VK, Sura ME, Hunter KW., Jr Conjugation of protein antigen to microparticulate beta-glucan from Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a new adjuvant for intradermal and oral immunizations. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;80:1053–1061. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00253-008-1618-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adachi K, Kawana K, Yokoyama T, Fujii T, Tomio A, Miura S, Tomio K, Kojima S, Oda K, Sewaki T, Yasugi T, Kozuma S, Taketani Y. Oral immunization with a Lactobacillus casei vaccine expressing human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 E7 is an effective strategy to induce mucosal cytotoxic lymphocytes against HPV16 E7. Vaccine. 2010;28:2810–2817. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aoki W, Ueda T, Tatsukami Y, Kitahara N, Morisaka H, Kuroda K, Ueda M. Time-course proteomic profile of Candida albicans during adaptation to a fetal serum. Pathog Dis. 2013;67:67–75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/2049-632X.12003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shibasaki S, Karasaki M, Ueda M. Combining proteomic strategies and molecular display technology for development of vaccines against Candida albicans. J Proteomics Bioinform. 2014;7:134–138. http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/jpb.1000313 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shibasaki S, Ueda M. Bioadsorption strategies with yeast molecular display technology. Biocontrol Sci; in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aukrust TW, Brurberg MB, Nes IF. Transformation of Lactobacillus by electroporation. Electroporation Protocols for Microorganisms Methods In Molecular Biology. 1995;47:201–208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1385/0-89603-310-4:201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Narita J, Okano K, Kitao T, Ishida S, Sewaki T, Sung MH, Fukuda H, Kondo A. Display of alpha-amylase on the surface of Lactobacillus casei cells by use of the PgsA anchor protein, and production of lactic acid from starch. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:269–275. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.72.1.269-275.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]