Abstract

Purpose

This study examined whether the perceived taste intensity of liquids with chemesthetic properties influenced lingua-palatal pressures and submental surface electromyography (sEMG) in swallowing, compared to water.

Method

Swallowing behaviors were studied in 80 healthy women, stratified by age-group and genetic taste-status. General Labeled Magnitude Scale ratings of taste intensity were collected for deionized water; carbonated water; 2.7 % w/v citric acid; and diluted ethanol. These stimuli were swallowed, with measurement of tongue-palate pressures and submental sEMG. Path analysis differentiated stimulus, genetic taste-status, age, and perceived taste intensity effects on swallowing. Signal amplitude during effortful saliva swallowing served as a covariate accounting for differences in participant strength.

Results

Significant differences in taste intensity were seen across liquids: citric acid > ethanol > carbonated water > water. Supertasters perceived greater taste intensity than nontasters. Lingua-palatal pressure and sEMG amplitudes were correlated with the strength covariate. Anterior palate pressures and sEMG amplitudes were significantly higher for the citric acid stimulus. Perceived taste intensity was a significant mediator of stimulus differences.

Conclusions

These data support the idea that sensory input transmitted via chorda tympani and trigeminal afferent pathways may lead to cortical facilitation and/or modulation of swallowing.

Keywords: Deglutition, swallowing, chemesthesis, taste, tongue pressure, electromyography

INTRODUCTION

Brain injuries, such as a stroke, progressive disease or trauma, often affect an individual’s ability to swallow food and liquids safely. Consequently, malnutrition, dehydration and aspiration pneumonia are common problems for these individuals. Only a small number of studies have investigated the effect of taste on swallowing although taste appears to influence some swallowing behaviors in healthy adults and individuals with neurogenic oropharyngeal dysphagia (Chee, Arshad, Singh, Mistry, & Hamdy, 2005; Ding, Logemann, Larson, & Rademaker, 2003; Krival & Bates; Leow, Huckabee, Sharma, & Tooley, 2007; Logemann et al., 1995; Michou, Mastan, Ahmed, Mistry, & Hamdy, 2012; Palmer, McCulloch, Jaffe, & Neel, 2005; Pelletier & Dhanaraj, 2006; Pelletier & Lawless, 2003; Plonk, Butler, Grace-Martin, & Pelletier, 2011; Rofes, Arreola, Martin, & Clave, 2012; Todd, Butler, Plonk, Grace-Martin, & Pelletier, 2012a, 2012b). It has been hypothesized that increased taste intensity will elicit heightened activation of sensory neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), which in turn may increase the stimulation of motor neurons in the nucleus ambiguus (NA), thus giving rise to a faster, stronger swallow response (Ding et al., 2003). Cortical facilitation of swallowing via trigeminal nerve afferent pathways and corticobulbar inputs to the NTS is also plausible.

In one study, high concentrations of taste stimuli with perceived irritant properties (indicating trigeminal as well as taste cranial nerve stimulation) evoked increased lingual swallowing pressure amplitudes compared to water in young healthy adults (Pelletier & Dhanaraj, 2006). The trigeminal nerve innervates the fungiform papillae (where taste buds lie) on the anterior tongue; the activation of these trigeminal sensory receptors results in oral sensations such as the fizziness of carbonation, the heat of chili peppers or the cool of menthol and has become known as chemesthesis (Green, 2000), a sensation of irritation produced by chemical stimulation. At this point, it is not known whether pure chemesthesis by itself elicits differences in swallowing behaviors, such as increased lingua-palatal swallowing pressures, nor whether taste stimuli that do not have chemesthetic components can influence swallowing behaviors. It also is not known how an individual’s perception and experience of a stimulus influences a swallow. Perception is different from the stimulus itself, e.g., a high concentration of a bitter substance may be perceived as very bitter, or not, due to individual variations in genetic, gender, aging and pathological conditions (Bartoshuk, 1993, 2000; Bartoshuk & Beauchamp, 1994; Bartoshuk et al., 2004; Bartoshuk, Duffy, & Miller, 1994; Bartoshuk, Duffy, Reed, & Williams, 1996; Bartoshuk, Rifkin, Marks, & Bars, 1986). The influence of perceived taste intensity on swallowing behaviors has not been evaluated to date.

Aging may be an important factor affecting lingua-palatal pressures and muscle activity in swallowing. Although aging does not appear to affect peak lingua-palatal swallowing pressures, it has been suggested that older adults are at increased risk of dysphagia because they have lower overall functional reserve (the difference in swallowing pressures seen between maximum isometric tasks and swallowing tasks) and a longer duration of lingual swallowing pressures (Nicosia et al., 2000; Robbins, Levine, Wood, Roecker, & Luschei, 1995). It is not known whether the experience of chemesthesis and its influence on swallowing physiology will diminish with age, although it has been posited that age-related differences in taste sensitivity might reduce the influence of taste stimuli on swallowing (Ding et al., 2003).

There is evidence that individuals who vary in their taste perception of the bitter compound 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) have different densities of fungiform papillae on their tongues, and consequently, experience differences in the perceived taste intensity of other taste stimuli (Bartoshuk, 1993; Reedy, Haines, & Campbell, 2005). This is due to their genetics. Homozygous individuals born with a recessive taste allele on chromosome 7 are labeled non-tasters because they are unable to taste the bitterness of PROP. Tasters of PROP fall into two groups due to incomplete dominance; heterozygous individuals (medium tasters) perceive moderate bitterness while those with homozygous PROP sensitivity are called supertasters and have an intense response to PROP. Given that supertasters have a higher density of fungiform papillae and apparent increased trigeminal sensation perception compared to non-tasters (Karrer et al., 1992), supertasters may logically be expected to display a heightened behavioral response to chemesthetic stimuli in the form of relatively greater increases in lingual swallowing pressures and sEMG signals of swallowing muscle activity compared to non-tasters. In other words, individual genetic taste-status may be a factor influencing swallowing behavior.

The aims of this study were to test the following hypotheses in healthy adult females with normal swallowing function:

Genetic taste-status and age will influence the perceived taste intensity of stimuli with putative trigeminal irritant properties;

Swallowing functional reserve will influence the amplitudes of lingua-palatal pressure and submental sEMG amplitudes seen in swallowing;

Stimuli with chemesthetic properties will elicit increased lingual swallowing pressures and submental sEMG amplitudes;

Perceived taste intensity will modulate the degree to which stimuli with chemesthetic properties influence swallowing behaviors (lingua-palatal pressures and submental sEMG activity).

METHODS

Participants

Eighty healthy adult women in two age groups participated in the study (n = 40 in each age group consisting of 18–35 yrs and 60+ yrs). Participants were recruited via fliers and newspaper/television ads in the local community. Each age group was further divided into 20 non-tasters and 20 supertasters (Table 1) based on their bitterness rating of 6-n-propylthiroucial (PROP) using the general Labeled Magnitude Scale (gLMS) (Figure 1). Only women were recruited because they are statistically more likely to be nontasters or supertasters than men (Bartoshuk et al., 1994). The number of subjects in each genetic taste group was prospectively determined to provide close to 0.90 power to detect differences between the groups should they exist, based on two decades of research by Bartoshuk (2004), and Keppel’s estimates of sample sizes for small, medium and large experimental effects in the behavioral sciences (Keppel, 1991). Inclusion criteria included healthy women living independently in the community, a score of ≥ 25 or greater on the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975), and a bitterness rating of ≤ 20 for non-taster status and ≥ 50 for supertaster status using the gLMS (Bartoshuk et al., 2004).

Table 1.

Mean Age (Standard Deviation) of Participants, Grouped by Age and Genetic Taste Status

| Young | Older | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-tasters | 25.8 (4.7) | 71.5 (8.7) |

| Supertasters | 26.5 (3.4) | 72.6 (7.4) |

Figure 1.

General Labeled Magnitude Scale (Bartoshuk et al.).

Initial Screening

A total of 222 women were screened for inclusion in the study. Ninety-seven participants failed to meet the inclusion criteria; all failed due to bitterness ratings indicating medium taster status except one older participant. She scored 25 on the MMSE and while that score would constitute acceptance into the study, her responses were extremely delayed and it was necessary to repeat the instructions numerous times, indicating significant cognitive impairment. One hundred twenty-five participants were accepted; fifteen could not return for the research session due to scheduling difficulties while 30 were not invited back because the quota in their age/genetic taste group was already met.

Stimuli

Five ml samples of four liquid stimuli were prepared using deionized water as the diluent (Millipore 60 Liter Progard™ Tank; Lot #FSKN82798, Serial #FYEN25621). Deionized water served as the neutral stimulus, without any expected taste or chemesthesis. A high-intensity sour stimulus, with both taste and chemesthetic properties, was made using de-ionized water and citric acid (0.128 M, 2.7% w/v - the same concentration as used in previous sour bolus dysphagia studies; Science Lab.com Lot #C6H807H20). A 50:50 dilution of deionized water and ethyl alcohol, 200 proof, absolute (Pharmco Products, Brookfield, CT 06804) was used as a chemesthetic (burning) stimulus expected to have neutral taste. Seltzer water (Polar™ Seltzer water with no sodium, Polar Beverages, Worcester, MA 01615), was used as a second chemesthetic (fizzy) but neutral taste stimulus. Samples were presented to each participant in a randomized order and chilled directly from a refrigerator (≤ 5° C) in 30 cc clear plastic cups labeled with a three-digit random number. Participants were blinded to the stimuli presented with the exception of the seltzer water. This stimulus was opened in the presence of the participant, measured and consumed immediately, in order to maintain the fizziness of the liquid during sampling.

Protocol

Participants were fitted with a nasal cannula, three surface electrodes applied under the chin (i.e., to the right and above the angle of the neck), and a two-bulb, air-filled lingua-palatal pressure array secured midline on the roof of the mouth just behind the upper teeth with a medical adhesive strip. Prior to any data collection, participants were asked to sit quietly for at least 5 min to adjust to the equipment. During this acclimatization period, participants completed a taste questionnaire verbally presented by the investigator. They rated their remembered intensity of sensations for past events or food experiences, such as the strongest smell of a flower and the strongest oral burn experienced (e.g., chili peppers) using the general Labeled Magnitude Scale (gLMS).

Data collection commenced with four saliva swallowing tasks (one effortful swallow and three regular-effort saliva swallows. The effortful swallow was collected for the purposes of capturing a strength measure analogous to functional reserve. Bolus swallowing then proceeded with the chilled, individually randomized taste samples, swallowed in a typical manner. Between each sample, participants were required to rinse their mouths at least three times with water or until no taste or chemesthestic mouthfeel was present. Immediately after swallowing each sample, participants were asked to state the taste quality perceived (sweet, sour, salty or bitter), if any, and to rate its intensity using the gLMS. Additionally, gLMS ratings for perceived burning/stinging (ethanol and citric acid stimuli) and perceived fizziness (carbonated water) were collected.

Data Processing

In the strong majority of cases, perceived taste intensity for the deionized water stimulus was rated as zero, reflecting that the person perceived an absence of taste for that stimulus. In order to include perceptions of taste intensity for the water stimulus in the subsequent statistical models, a random number generator was used to generate non-zero values between -3 and 3 as substitutions for the zero data values, with the mean and standard deviation values falling as close to zero as possible. Chemesthesis was rated as being present for the carbonated and ethanol stimuli. However, due to the lack of a broad distribution of perceived chemesthesis (either fizziness or burning/stinging) across a continuum for the stimuli used in this study, it was determined not to be appropriate to explore the intensity of perceived chemesthesis as a continuous covariate and potential modulator of swallowing behavior. Consequently, it was decided that perceived taste intensity would be the sensory quality used as the covariate in our subsequent analyses.

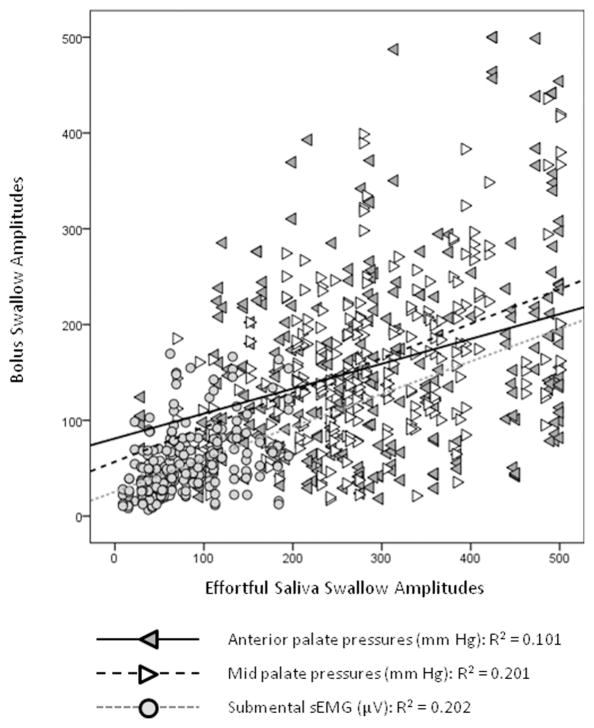

Based on prior examples in the literature, we recognized the possibility that the amplitude data for both lingua-palatal pressure and sEMG waveforms might vary across participants due to minor differences in sensor location, as well as between participant differences in strength and functional reserve. This issue has typically been addressed by normalizing data against a maximum effort reference task, typically a maximum isometric task (Steele & Huckabee, 2007; Youmans, Youmans, & Stierwalt, 2009). Given the absence of a maximum isometric reference task in the data collection protocol for this study, we investigated the dependence of the observed amplitudes for lingua-palatal pressure and sEMG data during bolus swallowing tasks on two possible reference values: a) the maximum amplitude value obtained across a baseline task of 3 non-effortful saliva swallows (Yeates, Steele, & Pelletier, 2010); and b) the amplitude value seen during a single effortful saliva swallow task. Linear regression showed that between 10 and 21% of the variation in amplitude values were explained by a participant’s effortful saliva swallowing amplitude, suggesting a probable influence of strength on observed amplitude values (see Figure 2). Consequently, it was decided that the subsequent ANOVA analyses involving amplitude should incorporate a covariate of effortful saliva swallow amplitude (recorded at the same sensor), to account for the influence of this value on the primary questions of the study.

Figure 2.

Relationship between bolus swallowing signal amplitudes and strength, as indexed by effortful saliva swallow signal amplitudes.

ANALYSIS

Statistics

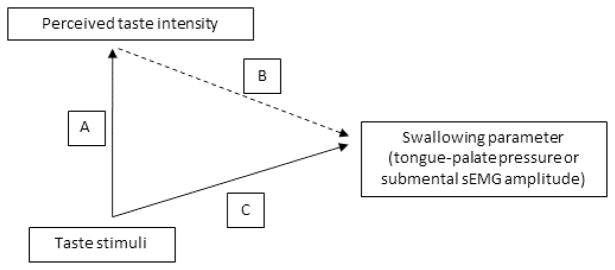

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all parameters. A path analysis approach was then taken as follows (see Figure 3 for an illustration):

Figure 3.

Path analysis used in this study to explore the influence of differences in perceived taste intensity for four liquids on swallowing behaviors.

A mixed model linear analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to evaluate the effects of stimulus, genetic taste-status and age-group on perceived taste intensity (Path A);

Mixed model linear ANOVAs were performed separately for each physiological waveform (1: anterior palate pressure bulb; 2: mid-palate pressure bulb; 3: submental sEMG) to determine the effects of stimulus, age-group and genetic taste-status on the dependent variable of amplitude (incorporating a covariate of effortful saliva swallow signal amplitude) (Path C);

Mixed model linear ANOVAs were performed separately for each physiological waveform and to determine the modulatory influence of a perceived taste intensity covariate on taste, genetic taste-status and age effects on the dependent variable of amplitude (Path B).

Anterior palate pressures will be referred to as Path Bi, with mid-palate pressures and submental sEMG referred to as paths Bii and Biii, respectively. For the mixed model ANOVAs, model fit was explored using a variety of different covariance structures. A heterogeneous compound symmetry structure was determined to have the best fit with the data.

RESULTS

Table 2 provides a cross-tabulation of perceived taste quality for the four different stimuli. The data verify that deionized water was perceived by the majority (85%) of participants as having no taste. When a taste was reported, it was usually classified as bitter. The citric acid was perceived by the majority of participants (84%) to be sour tasting; a bitter taste quality was reported by 15% of participants with this stimulus. The carbonated stimulus was either perceived to have no taste (40%) or a bitter taste (39%) in the majority of cases; this was the only stimulus where perceived saltiness was reported in more than one case. Finally, the diluted ethanol stimulus was perceived to be bitter in the majority of cases (79%) and to have no taste by 14% of participants. A burning/stinging sensation was reported for both the citric acid and the ethanol stimuli, with the intensity of the burning sensation being stronger for the ethanol, with a 95% confidence interval of 19–63 on the gLMS, and only mild (95% CI: 0–26) for the citric acid stimulus. It is noteworthy, that the highest degree of reported burning for the citric acid stimulus was seen in the older supertaster subgroup. Perceived fizziness was only rated for the carbonated stimulus, with a 95% confidence interval from 13–45 on the gLMS. The young non-taster subgroup reported the lowest intensity of perceived fizziness.

Table 2.

Frequencies (number and percent) of taste quality perception for the four stimuli in the experiment.

| Perceived Taste Quality | Stimulus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | High citric acid | Carbonated | Ethanol | |||||

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |

| Sweet | 1 | 1% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 3% | 1 | 1% |

| Sour | 1 | 1% | 67 | 84% | 6 | 8% | 5 | 6% |

| Salty | 1 | 1% | 1 | 1% | 8 | 10% | 0 | 0% |

| Bitter | 9 | 11% | 12 | 15% | 31 | 39% | 63 | 79% |

| No taste | 68 | 85% | 0 | 0% | 33 | 41% | 11 | 14% |

Table 3 shows descriptive statistics for perceptual ratings of taste intensity by age-group and genetic taste-status for the four stimuli. Perceived burning/stinging and fizziness ratings are also shown for the ethanol and citric acid and the carbonated stimuli, respectively. Descriptive statistics for lingua-palatal pressure and submental sEMG amplitudes are shown in mmHg and μV, respectively by sensor (anterior palate pressure bulb; mid-palate pressure bulb; submental sEMG sensor), age-group and genetic taste-status for the four stimuli in Table 4. Values in Table 4 are modeled at the mean values for the covariate of effortful saliva swallow amplitude for each signal.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for ratings of perceived taste intensity, burning and fizziness for four liquid stimuli by age-group and genetic taste status.

| Stimulus | Age-Group | Genetic Taste Status | Mean Perceived Taste Intensity (0–100 on the gLMS) | 95% Confidence Interval | Mean Perceived Burning (0–100 on the gLMS) | 95% Confidence Interval | Mean Perceived Fizziness (0–100 on the gLMS) | 95% Confidence Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| Water | Young | Nontaster | 0.10 | −8.92a | 9.12a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Supertaster | 1.40 | −7.62a | 10.42a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||

| Old | Nontaster | 0.00 | −9.02a | 9.02a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Supertaster | 2.30 | −6.72a | 11.32a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||

| Carbonated | Young | Nontaster | 9.60 | 0.58 | 18.62 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 20.35 | 13.19 | 27.51 |

| Supertaster | 12.20 | 3.18 | 21.22 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 30.35 | 19.35 | 41.35 | ||

| Old | Nontaster | 12.85 | 3.83 | 21.87 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 32.45 | 19.80 | 45.10 | |

| Supertaster | 14.60 | 5.58 | 23.62 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 32.55 | 22.12 | 42.98 | ||

| Ethanol | Young | Nontaster | 30.15 | 21.13 | 39.17 | 27.60 | 18.93 | 36.27 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Supertaster | 45.30 | 36.28 | 54.32 | 50.90 | 38.35 | 63.45 | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||

| Old | Nontaster | 42.45 | 33.43 | 51.47 | 44.40 | 29.02 | 59.78 | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Supertaster | 53.00 | 43.98 | 62.02 | 48.10 | 34.00 | 62.20 | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||

| Hi Sour | Young | Nontaster | 42.20 | 33.18 | 51.22 | 3.70 | 0 | 8.50 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Supertaster | 62.15 | 53.13 | 71.17 | 1.60 | 0 | 3.77 | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||

| Old | Nontaster | 55.20 | 46.18 | 64.22 | 2.55 | 0 | 6.09 | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Supertaster | 67.75 | 58.73 | 76.77 | 13.80 | 1.43 | 26.17 | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||

Non-zero values were artificially modeled to facilitate inclusion of the data in the statistical models

n/a = not applicable (specific chemesthetic sensations were not explored for these stimuli)

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics for swallowing parameters (lingua-palatal pressures and submental sEMG), shown by stimulus, age-group and genetic taste-status.

| Parameter | Stimulus | Age-Group | Genetic Taste Status | Mean Swallowing Amplitude | 95% Confidence Interval | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||||||||||||

| Anterior Palate Pressures (mm Hg) | Water | Young | Nontaster | 139.69a | 94.68 | 184.71 | ||||||||||

| Supertaster | 167.98a | 119.41 | 216.54 | |||||||||||||

| Old | Nontaster | 118.79a | 74.97 | 162.61 | ||||||||||||

| Supertaster | 152.17a | 108.22 | 196.11 | |||||||||||||

| Carbonated | Young | Nontaster | 142.14a | 97.12 | 187.16 | |||||||||||

| Supertaster | 206.94a | 159.18 | 254.69 | |||||||||||||

| Old | Nontaster | 170.80a | 126.98 | 214.62 | ||||||||||||

| Supertaster | 160.58a | 116.63 | 204.53 | |||||||||||||

| Ethanol | Young | Nontaster | 136.10a | 91.08 | 181.12 | |||||||||||

| Supertaster | 154.69a | 106.93 | 202.45 | |||||||||||||

| Old | Nontaster | 172.44a | 128.62 | 216.26 | ||||||||||||

| Supertaster | 134.87a | 90.92 | 178.82 | |||||||||||||

| Citric acid | Young | Nontaster | 167.10a | 122.09 | 212.12 | |||||||||||

| Supertaster | 194.30a | 146.54 | 242.06 | |||||||||||||

| Old | Nontaster | 162.28a | 118.45 | 206.09 | ||||||||||||

| Supertaster | 167.43a | 123.48 | 211.38 | |||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Mid-Palate Pressures (mm Hg) | Water | Young | Nontaster | 140.85b | 107.52 | 174.17 | ||||||||||

| Supertaster | 167.74b | 132.78 | 202.69 | |||||||||||||

| Old | Nontaster | 146.09b | 114.42 | 177.76 | ||||||||||||

| Supertaster | 150.95b | 118.52 | 183.37 | |||||||||||||

| Carbonated | Young | Nontaster | 136.23b | 102.91 | 169.55 | |||||||||||

| Supertaster | 181.53b | 147.14 | 215.93 | |||||||||||||

| Old | Nontaster | 166.11b | 134.44 | 197.78 | ||||||||||||

| Supertaster | 161.49b | 129.07 | 193.92 | |||||||||||||

| Ethanol | Young | Nontaster | 129.46b | 96.14 | 162.78 | |||||||||||

| Supertaster | 174.75b | 140.35 | 209.14 | |||||||||||||

| Old | Nontaster | 160.08b | 128.41 | 191.75 | ||||||||||||

| Supertaster | 154.40b | 121.97 | 186.82 | |||||||||||||

| Citric acid | Young | Nontaster | 167.48b | 134.16 | 200.80 | |||||||||||

| Supertaster | 182.75b | 148.35 | 217.15 | |||||||||||||

| Old | Nontaster | 149.43b | 117.76 | 181.10 | ||||||||||||

| Supertaster | 171.05b | 138.62 | 203.47 | |||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Submental sEMG (μV) | Water | Young | Nontaster | 27.45c | 14.50 | 40.40 | ||||||||||

| Supertaster | 39.54c | 26.01 | 53.07 | |||||||||||||

| Old | Nontaster | 44.45c | 32.22 | 56.67 | ||||||||||||

| Supertaster | 48.37c | 36.21 | 60.54 | |||||||||||||

| Carbonated | Young | Nontaster | 25.86c | 13.18 | 38.54 | |||||||||||

| Supertaster | 40.09c | 26.54 | 53.64 | |||||||||||||

| Old | Nontaster | 50.44c | 38.22 | 62.66 | ||||||||||||

| Supertaster | 51.50c | 39.34 | 63.66 | |||||||||||||

| Ethanol | Young | Nontaster | 40.66c | 27.98 | 53.34 | |||||||||||

| Supertaster | 50.90c | 37.36 | 64.43 | |||||||||||||

| Old | Nontaster | 68.59c | 56.37 | 80.81 | ||||||||||||

| Supertaster | 65.14c | 52.98 | 77.31 | |||||||||||||

| Citric acid | Young | Nontaster | 55.29c | 42.38 | 68.19 | |||||||||||

| Supertaster | 56.99c | 43.44 | 70.54 | |||||||||||||

| Old | Nontaster | 73.78c | 61.56 | 86.00 | ||||||||||||

| Supertaster | 68.04c | 55.87 | 80.20 | |||||||||||||

Modeled at the mean covariate value for effortful saliva swallow strength of 292.87 mm Hg.

Modeled at the mean covariate value for effortful saliva swallow strength of 279.58 mm Hg.

Modeled at the mean covariate value for effortful saliva swallow strength of 75.27 μV.

Path A

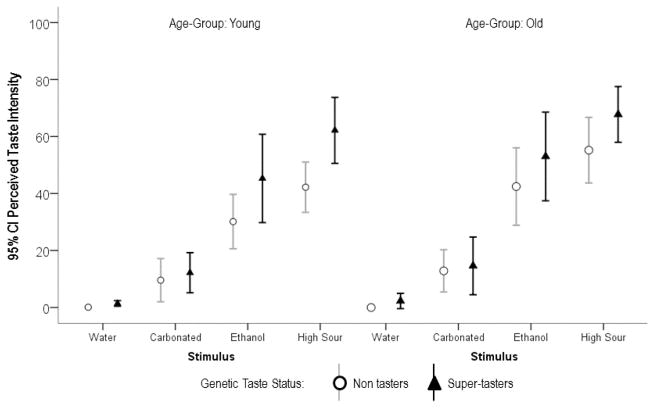

Regarding the effects of stimulus, age-group and genetic taste-status on perceived taste intensity, statistically significant differences between stimuli [F(3, 228) = 155.64, p = 0.000] and genetic taste-status groups [F(1, 76) = 8.59, p = 0.004] were observed. These results showed an ascending gradient of perceived intensity from water to carbonation, to ethanol, to the citric acid stimulus, with significant increases between each stimulus along this gradient. Super-tasters reported significantly higher perceived taste intensity than non-tasters for all stimuli. Additionally, there was a significant interaction between these two factors [F(3, 228) = 3.14, p = 0.026], such that the differences in taste intensity across stimuli were perceived as greater by the supertasters than the differences perceived by the non-tasters. The difference in perceived intensity between age-groups was also significant [F(1,76) = 3.984, p = 0.05], with heightened intensity reported by the older participants. There were no statistically significant interactions with age for taste intensity perception. These results are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Results of the Path A analysis, showing differences in perceived taste intensity for four liquids as a function of age-group and genetic taste status.

Path C

Genetic taste status was not found to have any influence on lingua-palatal pressure or sEMG swallowing amplitudes. Observed amplitudes for liquid pressure and sEMG were all significantly positively correlated with the covariate of effortful saliva swallow amplitude, as shown previously in Figure 3. A statistically significant main effect of stimulus was seen for lingua-palatal pressure amplitude at the anterior bulb [F(3, 203.17) = 3.75, p = 0.012], with the greatest pressure amplitudes elicited by the citric acid stimulus and these being significantly higher than those seen for water. Anterior palate pressures varied significantly according to, and displayed a positive correlation with, the covariate of effortful saliva swallow amplitude [F(1, 66.97) = 12.29, p = 0.001]. No stimulus effects were seen for lingua-palatal pressure amplitudes at the mid bulb, but these also varied significantly in relation to the pressure amplitudes seen in the effortful saliva swallowing task [F(1, 69.00) = 29.21, p = 0.000]. For the sEMG data, a significant main effect of stimulus was seen [F(3, 162.98) = 20.81, p = 0.000], with both the citric acid acid and the ethanol stimuli eliciting higher amplitudes than the water and carbonated stimuli. Significantly lower sEMG amplitudes were seen in the older participant group [F(1, 67.98) = 11.66, p = 0.001], and sEMG amplitudes again varied significantly as a function of, and displaying a positive correlation with effortful saliva swallow task values [F(1, 67.89) = 50.99, p = 0.000].

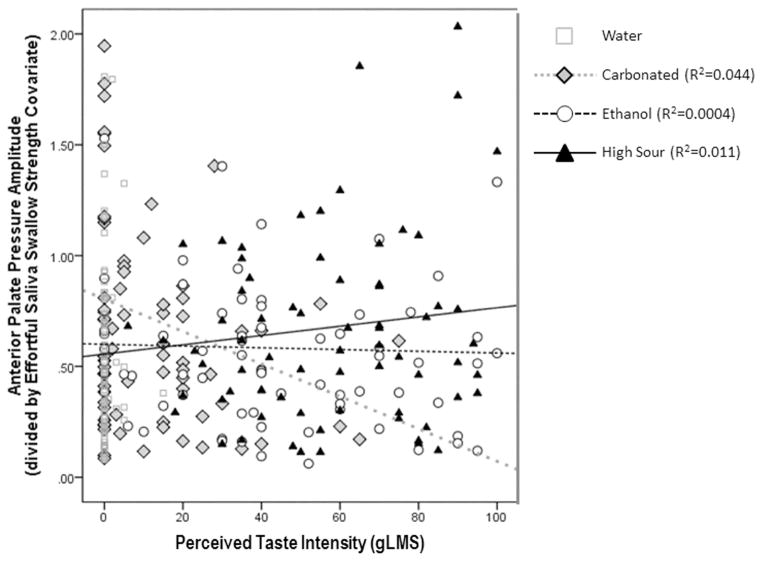

Path Bi (Anterior Palate Pressures)

At the level of the full statistical model, significant effects of stimulus [F(3, 177.42) = 5.477, p = 0.001] and effortful saliva swallow amplitude [F(1, 142.58) = 4.95, p = 0.028, positive correlation], were seen for anterior palate pressures, as described in the prior explorations for path C. A number of significant 2-way and 3-way interactions were also observed between factors of stimulus, effortful saliva swallow strength, genetic taste status and perceived taste intensity. Given that age did not show any significant influence on these results, it was removed from the model, leaving a statistically significant 3-way interaction between stimulus, effortful saliva swallow strength and perceived taste intensity [F(3, 203.88 = 2.70, p = 0.047] and significant main effects of stimulus [F(3, 200.59 = 4.15, p = 0.007], effortful saliva swallow strength [F(1, 133.64 = 6.22, p = 0.014] and a 2-way stimulus X perceived intensity interaction [F(3, 203.89 = 3.36, p = 0.02]. Figure 5 illustrates these effects, with anterior palate pressure amplitudes shown in values transformed relative to effortful saliva swallow strength. Here, it is seen that anterior palate pressures decline with increasing intensity of the carbonated stimulus, and show the opposite pattern, increasing amplitudes with increasing intensity, with the citric acid stimulus. There is no apparent effect of taste intensity for the ethanol stimulus.

Figure 5.

Results of the Path Bi analysis, showing the influence of perceived differences in taste intensity for four liquids on the amplitude of anterior tongue-palate pressures.

Path Bii (Mid-palate Pressures)

At the level of the full statistical model, a single significant main effect of effortful saliva swallow strength [F(1, 140.47 = 12.76, p = 0.000] was seen for mid-palate pressures, with higher pressures seen in those with stronger effortful saliva swallow values. This remained the case when age-group was removed from the model, with the influence of effortful saliva swallow strength being slightly enhanced [F(1, 127.99 = 16.81, p = 0.000].

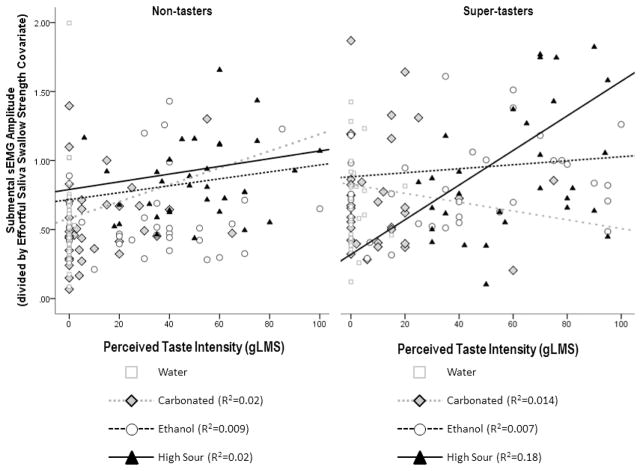

Path Biii (Submental sEMG)

Similarly, submental sEMG amplitudes showed a single significant effect of effortful saliva swallow amplitude [F(1, 152.16) = 28.14, p = 0.000, positive correlation], at the level of the full model. When simplified to remove consideration of the influence of age-group, additional findings in the form of a significant 4-way interaction (stimulus X genetic taste status X effortful saliva swallow strength X perceived intensity) [F(3, 211.44 = 2.98, p = 0.03] as well as a significant 2-way stimulus X effortful saliva swallow strength interaction [F(3, 197.10 = 7.59, p = 0.000] and a significant main effect of stimulus [F(3, 197.57 = 2.98, p = 0.033] became apparent. As illustrated in Figure 6, with sEMG amplitudes displayed in valued transformed relative to the effortful saliva swallow strength covariate, all three chemesthetic stimuli showed a weak trend of eliciting greater amplitudes of submental muscle contraction with greater perceived taste intensities in the non-tasters. However, in the supertaster group, a much stronger effect is seen for the citric acid stimulus, which elicited stronger amplitudes of muscle contraction at higher perceived stimulus intensities.

Figure 6.

Results of the Path Biii analysis, showing the influence of perceived differences in taste intensity for four liquids on the amplitude of submental sEMG in nontaster and supertaster subgroups.

DISCUSSION

This is, to our knowledge, the first study in the dysphagia literature to explore differences in swallowing with chemesthetic stimuli as a function of the perceived taste intensity of those stimuli, while controlling for genetic taste status. A number of key findings are worthy of discussion.

Beginning with stimulus perception, it is interesting to note that our participants reported the perception of a taste in cases where we had expected there to be no taste. The ethanol stimulus was reported to have a bitter taste in the majority of cases, while the carbonated water was perceived as either bitter or salty by almost half of the participants. We suspect that when faced with the binary task of indicating whether or not they perceived a taste, these participants chose to report a taste when the nature of the sensation was more likely to be chemesthetic. The perception of saltiness with the carbonated water may be explained by the fact that sodium bicarbonate was an ingredient in the recipe. Interestingly, even deionized water was reported to have a bitter taste by 11% of the participants. The reported perceptions of chemesthesis in this study were associated with specific stimuli. The carbonated stimulus was reported to be fizzy, while the citric acid stimulus was perceived to cause a slight burning/stinging sensation, in comparison to the ethanol, which was perceived as causing a moderate burning/stinging sensation.

It is clear that supertasters experience heightened taste intensities for the carbonated, ethanol and citric acid stimuli used in this study. Both supertasters and nontasters in our study sample reported a gradient of perceived intensity across stimuli, with the highest reported intensities seen for the 2.7% citric acid solution. This finding confirms that participants in prior studies involving a sour stimulus of this concentration were likely perceive these sour stimuli as being of high intensity. Interestingly, however, carbonated stimuli had a much lower perceived taste intensity than the citric acid stimulus in both genetic taste subgroups in our sample. The ethanol stimulus, which is unlikely to be practical for use in clinical settings, also elicited strong ratings in both groups for taste intensity, but these were not as strong as the ratings seen for the citric acid stimulus. These findings would appear to be convergent with the available literature suggesting that sour stimuli may have the potential to influence swallowing behavior. However, evidence of different perceived intensities between nontasters and supertasters suggests that clinicians may need to consider genetic taste status as a factor that influences a patient’s likelihood of responding favorably to manipulations of bolus taste and chemesthesis.

Turning to the Path C results, exploring swallowing parameters without consideration of perceived taste intensity, there are several noteworthy findings. First, it is clear that both tongue-palate pressure measures and submental sEMG measures in this study varied as a function of the participant’s strength, as indexed by the effortful saliva swallowing task covariate. While inter-participant variations have been long recognized to be a factor in EMG data, requiring normalization or transformation for interpretation, this study suggests that the same is true for lingua-palatal pressures. When the effortful saliva swallow strength covariate is taken into account, these data show a remarkable lack of variation in tongue-palate pressures attributable to age. This finding is consistent with prior literature suggesting that age-related differences in tongue pressure and functional reserve may be limited to differences in maximal effort tasks, and may not be evident in bolus swallowing tasks (Nicosia et al., 2000; Youmans et al., 2009).

Second, the path C analyses in this study show an interesting pattern of variations in anterior tongue-palate pressures and submental sEMG measures across stimuli, but no such pattern for the mid-palate pressure data. In both cases, the citric acid stimulus elicited stronger amplitudes than water. The lack of any stimulus-related differences in mid-palate pressure may reflect greater inherent variability in pressure measures at this location, perhaps attributable to differences in palatal vault height across participants, as reported in prior studies (Steele, Bailey, & Molfenter, 2010). Alternatively, this finding may suggest that differences in swallowing behavior related to the experience of tasting a stimulus occur primarily in the anterior oral cavity and influence the initial driving forces of the anterior tongue. Genioglossus muscle activity is likely to be captured in the composite submental sEMG signal, perhaps providing a rationale for the fact that this effect was also seen in those data. Quite why stimulus-dependent heightened amplitudes of anterior tongue-palate pressure are not translating to similar patterns at a more distal pressure sensor location remains unclear.

When the influence of perceived taste intensity is factored into the analysis of swallowing behavior (path B), the results of this study provide further support for the potential of high intensity sour stimuli to influence swallowing. Higher amplitudes of anterior tongue-pressure and submental sEMG were seen with greater perceived intensity of this stimulus, with the sEMG effect being particularly strong in supertasters.

This study is not without limitations. The protocol included a single effortful saliva swallow task as a means of measuring differences in strength across participants. This measure is not the same as the conventional approach to measuring functional reserve, which involves a comparison of maximum isometric tongue-palate pressure tasks to regular effort saliva swallows (Steele, 2012). A single repetition of this task may also be inadequate to properly characterize variability in strength across participants. Additionally, the data on perceived taste intensity do not take the palatability or hedonics of the taste experience into account. Future work should explore both the intensity of a stimulus and the degree to which a participant likes or dislikes the stimulus, to properly understand the influence of these sensory parameters on swallowing behaviors.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this study provides evidence that high intensity sour stimuli do influence the amplitudes of anterior tongue-palate pressures and submental muscle contraction seen in swallowing. Importantly, variations in swallowing behavior attributable to this taste stimulus are mediated by the perceived sensory intensity of the stimulus and differ between those who are classified as supertasters and nontasters, based on genetic factors. This finding suggests that it may be important to understand taste genetics when determining whether manipulations of stimulus taste may be of benefit for patients with dysphagia. Further, the three stimuli explored in this study were chosen based on their presumed chemesthetic properties, that is, activation of trigeminal nerve receptors. Chemesthesis is different than taste perception. Future studies are needed to tease out the different contributions of taste intensity and chemesthesis intensity on swallowing, using a continuum of chemesthetic intensities in addition to taste intensities.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided through an American Speech-Language Hearing Foundation New Investigator award to the first author. Additional funding was provided by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and Johns Hopkins Hospital. The second author acknowledges funding from the NIDCD and the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute – University Health Network, which receives funding from the Provincial Rehabilitation Research program of the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the Ministry. The authors gratefully acknowledge assistance and advice from Karen Grace-Martin with the statistical analyses, and from Drs. Linda Bartoshuk, Christy Ludlow and Rebecca German regarding analysis and interpretation of the data.

References

- Bartoshuk LM. Genetic and pathological taste variation: what can we learn from animal models and human disease? Ciba Found Symp. 1993;179:251–262. doi: 10.1002/9780470514511.ch16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoshuk LM. Comparing sensory experiences across individuals: Recent psychophysical advances illuminate genetic variation in taste perception. Chemical Senses. 2000;25(4):447–460. doi: 10.1093/chemse/25.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoshuk LM. Psychophysics: a journey from the laboratory to the clinic. Appetite. 2004;43(1):15–18. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoshuk LM, Beauchamp GK. Chemical senses. Annu Rev Psychol. 1994;45:419–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.45.020194.002223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoshuk LM, Duffy VB, Green BG, Hoffman HJ, Ko CW, Lucchina LA, Weiffenbach JM. Valid across-group comparisons with labeled scales: The gLMS versus magnitude matching. Physiology and Behavior. 2004;82(1):109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoshuk LM, Duffy VB, Miller IJ. PTC/PROP tasting: anatomy, psychophysics, and sex effects. Physiol Behav. 1994;56(6):1165–1171. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90361-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoshuk LM, Duffy VB, Reed D, Williams A. Supertasting, earaches and head injury: genetics and pathology alter our taste worlds. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1996;20(1):79–87. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(95)00042-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoshuk LM, Rifkin B, Marks LE, Bars P. Taste and aging. J Gerontol. 1986;41(1):51–57. doi: 10.1093/geronj/41.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chee C, Arshad S, Singh S, Mistry S, Hamdy S. The influence of chemical gustatory stimuli and oral anaesthesia on healthy human pharyngeal swallowing. Chemical Senses. 2005;30(5):393–400. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bji034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding R, Logemann JA, Larson CR, Rademaker AW. The effects of taste and consistency on swallow physiology in younger and older healthy individuals: a surface electromyographic study. Journal of Speech Language & Hearing Research. 2003;46(4):977–989. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/076). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BG. Measurement of sensory irritation of the skin. Am J Contact Dermat. 2000;11(3):170–180. doi: 10.1053/ajcd.2000.7185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karrer T, Bartoshuk LM, Conner E, Fehrenbaker S, Grubin D, Snow D. PROP status and its relationship to the perceived burn intensity of capsaicin at different tongue loci. Chem Senses. 1992;17:649. [Google Scholar]

- Keppel G. Design and analysis: A researcher’s handbook (4th edition) Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1991. The sensitivity of an experiment: Effect size and power; pp. 63–92. [Google Scholar]

- Krival K, Bates C. Effects of club soda and ginger brew on linguapalatal pressures in healthy swallowing. Dysphagia. 2012;27(2):228–239. doi: 10.1007/s00455-011-9358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leow LP, Huckabee ML, Sharma S, Tooley TP. The influence of taste on swallowing apnea, oral preparation time, and duration and amplitude of submental muscle contraction. Chem Senses. 2007;32(2):119–128. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjl037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logemann JA, Pauloski BR, Colangelo L, Lazarus C, Fujiu M, Kahrilas PJ. Effects of a sour bolus on oropharyngeal swallowing measures in patients with neurogenic dysphagia. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research. 1995;38(3):556–563. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3803.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michou E, Mastan A, Ahmed S, Mistry S, Hamdy S. Examining the role of carbonation and temperature on water swallowing performance: A swallowing reaction-time study. Chem Senses. 2012;37(9):799–807. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjs061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicosia MA, Hind JA, Roecker EB, Carnes M, Doyle J, Dengel GA, Robbins J. Age effects on the temporal evolution of isometric and swallowing pressure. Journals of Gerontology Series A-Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences. 2000;55(11):M634–640. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.11.m634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer PM, McCulloch TM, Jaffe D, Neel AT. Effects of a sour bolus on the intramuscular electromyographic (EMG) activity of muscles in the submental region. Dysphagia. 2005;20(3):210–217. doi: 10.1007/s00455-005-0017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier CA, Dhanaraj GE. The effect of taste and palatability on lingual swallowing pressure. Dysphagia. 2006;21(2):121–128. doi: 10.1007/s00455-006-9020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier CA, Lawless HT. Effect of citric acid and citric acid-sucrose mixtures on swallowing in neurogenic oropharyngeal dysphagia. Dysphagia. 2003;18(4):231–241. doi: 10.1007/s00455-003-0013-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plonk DP, Butler SG, Grace-Martin K, Pelletier CA. Effects of chemesthetic stimuli, age, and genetic taste groups on swallowing apnea duration. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145(4):618–622. doi: 10.1177/0194599811407280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reedy J, Haines PS, Campbell MK. The influence of health behavior clusters on dietary change. Prev Med. 2005;41(1):268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins J, Levine R, Wood J, Roecker EB, Luschei E. Age effects on lingual pressure generation as a risk factor for dysphagia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50(5):M257–M262. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.5.m257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rofes L, Arreola V, Martin A, Clave P. Natural capsaicinoids improve swallow response in older patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia. Gut. 2012 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM. A comparison of approaches for measuring functional tongue-pressure reserve. Paper presented at the 2nd Annual Congress of the European Society for Swallowing Disorders; Barcelona. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Bailey GL, Molfenter SM. Tongue pressure modulation during swallowing: water versus nectar-thick liquids. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2010;53(2):273–283. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/09-0076). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Huckabee ML. The influence of oro-lingual pressure on the timing of pharyngeal pressure events. Dysphagia. 2007;22(1):30–36. doi: 10.1007/s00455-006-9037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd JT, Butler SG, Plonk DP, Grace-Martin K, Pelletier CA. Effects of chemesthetic stimuli mixtures with barium on swallowing apnea duration. Laryngoscope. 2012a;122(10):2248–2251. doi: 10.1002/lary.23511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd JT, Butler SG, Plonk DP, Grace-Martin K, Pelletier CA. Main taste effects on swallowing apnea duration in healthy adults. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012b;147(4):678–683. doi: 10.1177/0194599812450839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeates EM, Steele CM, Pelletier CA. Tongue pressure and submental surface electromyography measures during noneffortful and effortful saliva swallows in healthy women. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2010;19(3):274–281. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2010/09-0040). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youmans SR, Youmans GL, Stierwalt JA. Differences in tongue strength across age and gender: is there a diminished strength reserve? Dysphagia. 2009;24(1):57–65. doi: 10.1007/s00455-008-9171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]