Abstract

The neuroscience and psychological literatures suggest that talking about previous violence and abuse may not only be beneficial, as previously believed, but may also be associated with risks. Thus, studies on such topics introduce ethical questions regarding the risk–benefit ratio of sensitive research. We performed a systematic review of participants’ experiences related to sensitive research and compared consequent harms, benefits, and regrets among victims and nonvictims of abuse. Thirty studies were included (4 adolescent and 26 adult studies). In adolescent studies, 3% to 37% of participants (median: 6%) reported harms, but none of these studies measured benefits or regrets. Among adults, 4% to 50% (median: 25%) reported harms, 23% to 100% (median: 92%) reported benefits, and 1% to 6% (median: 2%) reported regrets. Our results suggest that the risk–benefit ratio related to sensitive research is not unfavorable, but there are gaps in the evidence among adolescents.

Sensitive research topics include those that are highly private and potentially psychologically traumatic. Substance use, sexual practices, violence and abuse, death, accidents, combat (including war), and natural disasters might all be considered sensitive research topics. Since the 1930s and 1940s, research has increasingly focused on sensitive topics, predominantly owing to the epidemics of illicit drug use, AIDS, and teenage pregnancies.1,2 There is a clear scientific rationale for research on sensitive topics to generate accurate information about prevalence, risk and protective factors, and intervention strategies. The self-reports of research participants are one of the most efficient data collection methods to gather such information.

In the clinical arena of trauma-related disorders, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), earlier approaches of debriefing and “talking through” traumatic experiences were thought to be helpful intervention strategies to manage trauma and reduce risk. More recent evidence, however, suggests that such approaches may be harmful and may lead to retraumatization.3 The past decade has also seen an emerging neuroscience literature focusing on memory consolidation and reconsolidation; this literature suggests that reliving a memory might strengthen the memory trace.4 Taken together, psychological and neuroscience evidence suggests that there may be both risks and benefits of trauma-based clinical work.

There has also been a debate in research settings as to whether recalling and answering questions about past trauma or abuse has negative or positive consequences for study participants.5–10 Some argue that asking about abuse might be upsetting, harmful, and stigmatizing and may lead to retraumatization; that survivors might not be emotionally stable enough to assess risk or seek help; and that researchers have an obligation to protect survivors from questions about their experiences. In contrast, others suggest that disclosure in the context of research participation may be followed by emotional relief, that participants identify such disclosure as beneficial, and that most participants do not regret or negatively appraise their research experience.11–18 Furthermore, it has been suggested that the emotional distress experienced by participants involved in sensitive research is an indicator of emotional engagement with a research project rather than an indicator of harm.5

Given this debate, it is important to examine the literature regarding harms, benefits, and regrets in the context of sensitive research. A key consideration is differences between those with previous exposure to violence and abuse (victimization or perpetration) and those who have not been exposed. Another consideration is whether responses to research differ by gender. Females might be more vulnerable to the harms of research participation because prevailing norms supporting gender power inequities and male violence against women and girls may limit the accessibility of support during and after participation. Responses to participation may also be age dependent. In particular, adolescents who are exposed to abuse might be particularly vulnerable because they may need more support than adults during and after the research, and such support may be less accessible to them.

Given the uncertainty regarding the risks, benefits, and risk-to-benefit ratio of participating in sensitive research, we conducted a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies investigating adolescents’ and adults’ experiences of participating in studies that included sensitive questions regarding violence and abuse (including intimate partner violence [IPV]) victimization and perpetration. We compared the consequent harms, benefits, and regrets among individuals who had been victims and perpetrators of violence or abuse with those of individuals who had not been victims or perpetrators. Furthermore, we investigated whether there were gender and age differences in the reporting of harms and benefits of research experience. Our goal was to produce evidence to guide researchers and ethics committees in avoiding underprotection or overprotection of human participants in research on violence and abuse.

METHODS

We performed a systematic review in search of all literature relevant to topics related to sensitive research. Here we outline our search strategy and inclusion criteria and describe how we assessed potential risk of bias in the studies included.

Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

We conducted an electronic database search of PubMed, Academic Search Premier, and PsycARTICLES to identify published, peer-reviewed journal articles. The following search terms were used: (1) “ethics” and “sensitive topics” or “sensitive questions” and “research” and “adolescents” and “trauma” and “IPV” or “childhood abuse,” (2) “sensitive topics” and “research experience,” (3) “sensitive research” and “ethics” and “research experience,” and (4) “violence” and “trauma research.” Restrictions for language (English) and species (humans) were incorporated.

To be included, studies were required to have examined adults’ or adolescents’ experience of harms and benefits of participation in research. Also, they were required to have examined experiences of traumatic events (interpersonal violence or abuse) or to have asked about PTSD symptoms. Finally, they were required to have been published in academic peer-reviewed journals and in English; however, there were no date restrictions.

Risk of Bias

We assessed the risk of bias associated with the included studies to establish the extent to which the evidence was based on high-quality studies and was thus convincing. We used an amended version of the assessment tool developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project (http://www.ephpp.ca/Tools.html) to assess the risk associated with the quantitative studies included in our review. Given that most of these studies (70%) were cross sectional, we amended the instrument by excluding the criteria relating predominantly to experimental studies, namely the assessments of blinding and withdrawal or dropout. The blinding and withdrawal or dropout criteria for the 5 quantitative studies that were experimental or longitudinal were assessed separately (for details of our risk of bias evaluation, see Tables S1 and S2, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

We used the quality assessment instrument described by Walsh and Downe to assess the 3 qualitative studies.19 The risk of bias associated with each study was assessed by the first author, after which a random sample of 5 quantitative studies and 2 qualitative studies were assessed by 2 of the other authors.

We reviewed all of the eligible articles with respect to reported evidence of harms, benefits, and regrets across gender, age, victim status (victim or nonvictim), and perpetrator status (perpetrator or nonperpetrator). The results were systematically recorded (Tables S3 and S4, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). We did not set out to perform a meta-analysis given the heterogeneity of measures and designs across studies. Recorded results across all studies were subsequently summarized in a condensed table separately for adolescent and adult studies (Table 1). We conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding the studies at high risk of bias to assess the impact on our findings and whether this would change our conclusions.

TABLE 1—

Harms, Benefits, and Regrets Associated With Participation in Sensitive Research: Summary of Adolescent and Adult Studies Conducted From 1997 to 2013

| Study | Type of Violence Assessed | Harms | Benefits | Regrets | Do Victims or Nonvictims Report More Harms, Benefits, or Regrets? | Do Perpetrators or Nonperpetrators Report More Harms, Benefits, or Regrets? | Which Gender Reports More Harms, Benefits, or Regrets? | Do Younger Or Older Participants Report More Harms, Benefits, or Regrets? |

| Studies among adolescents | ||||||||

| Langhinrichsen-Rohling et al.26 (2006) | Physical and sexual abuse | 2.5%–7.5% upset | NR | NR | Physical and sexual abuse victims reported being upset | NR | Female participants reported interest | NR |

| Zajac et al.33 (2011) | Physical assault and abuse, sexual assault, witnessed community and parental violence | 5.7% distressed; 0.2% remained upset; 0.1% requested counseling (baseline); attrition rate: 29% (12-month follow-up) | NR | NR | Physical and sexual abuse victims reported distress | NR | Female participants reported distress | NR |

| Priebe et al.35 (2010) | Sexual abuse | 17.4% reported unpleasant feelings; 9.7% said that such questions should not be asked; 11% said that such questions can have an unfortunate impact; 17.7% said that the information collected was too private | NR | NR | Sexual abuse victims reported discomfort | Authors did not report on perpetrators’ risk of harm separately from victims’ risk of harm | NR | NR |

| Ybarra et al.36 (2009) | Verbal, physical, and sexual abuse | 23% upset (baseline); 77% of the participants did not complete the survey and 70% did complete the survey (13-month follow-up) | NR | NR | No differences with respect to participants’ reports of being upset | No differences with respect to participants’ reports of being upset | Female participants reported being upset | Younger participants reported being upset |

| Studies among adults | ||||||||

| Black et al.11 (2006) | Family and sexual violence, IPV | Subgroup 1a: 15.9% were upset from recalling violence; subgroup 2b: 11.4% were upset | More than 95% of subgroup 1 and 92.4% of subgroup 2 believed that such questions should be asked | NR | No differences between subgroups 1 and 2 regarding whether such questions should be asked | NR | Women in subgroups 1 and 2 reported being upset; no differences between groups in belief that such questions should be asked |

NR |

| Carlson et al.12 (2003) | Childhood physical and sexual abuse | 70% reported low levels of distress; 24% were very/extremely upset; 6.6% stopped the interview because they were upset | 51% reported that research participation was somewhat useful; of the 24% who were highly upset, 37% found reported that participation was somewhat useful | NR | Victims of higher (vs lower) levels of trauma reported being upset | NR | NR | NR |

| Decker et al.13 (2011) | Assessment 1: child maltreatment. Assessment 2: emotionally evocative photographs and sounds. Assessment 3: 1-week follow-up | 1.3%–27.8% reported the experience as a bother; 8.9%–25.3% reported no bother | All assessments: 26.6%–30.4% reported increased self-insight | NR | Assessment 1: victims reported the experience as a bother. Assessments 2 and 3: nonvictims reported being bothered by painful insights about others. Assessments 1 and 3: victims reported the research as helpful. All assessments: victims reported distress but also reported that the research was helpful | NR | NR | NR |

| Gekoski et al.14 (2009) | Experiences of secondary victimization | 50% upset/distressed | All gained something positive | No regret | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Griffin et al.15 (2003) | Physical assault, rape, domestic violence | Acute physical/sexual assault survivors reported that research participation was not very distressing; domestic violence survivors: 42% reported strong/very strong emotions | Acute physical/sexual assault survivors reported that research participation was largely interesting | 5% of acute physical/sexual assault survivors reported regret; 2% of domestic violence survivors reported regret | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Kuyper et al.16 (2010) | Sexual abuse | 16.5% were feeling down; 7.8% were sad; 3.5% needed help | 96.5% reported positive feelings | NR | Sexual coercion victims reported distress and a need for help but also positive feelings | NR | Women reported distress | Younger participants reported positive feelings |

| Newman et al.17 (1999) | Child maltreatment | 7% reported increase and 3% reported decrease in unexpected upset (48 hours after follow-up) | 24% reported benefits at baseline, 86% at 3–12-month follow-up, 74% 48 hours after follow-up | 0.09% reported regret at 3–12-month follow-up; no regret 48 hours after follow-up |

Sexual abuse victims reported unexpected upset | NR | NR | NR |

| Walker et al.18 (1997) | Early childhood and adult forms of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse and neglect | 13% unexpectedly upset | More than 25% gained something positive; 13% reported no gain | 76% reported no regret; 5% reported regret |

Victims of the combined types of abuse reported distress | NR | NR | NR |

| DePrince and Chu20 (2008) | Interpersonal abuse (type not specified) | Participants’ mean personal benefit scores were greater than their mean emotional reaction and perceived drawback scores | Participants’ mean personal benefit scores were greater than their mean emotional reaction and perceived drawback scores | NR | NR | NR | Men reported regret and a negative experience; women believed that the research was important | Older participants reported unexpected and negative emotions but also benefits |

| Cook et al.21 (2011) | Comparison of a control questionnaire without sensitive questions with 5 questionnaires involving increasing levels of sensitive questions (ranging from stressful events to sexually violating events) | Low negative affect reported across all questionnaires | Participants administered the control questionnaire reported higher levels of positive affect than those completing the other questionnaires | No regrets reported across any questionnaires | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Ferrier-Auerbach et al.22 (2009) | Effects of trauma survey (questions on combat/war exposure) vs nontrauma survey | Mean scores for sadness, tension, and unexpected upset were higher among participants who completed the trauma survey | No differences between trauma and nontrauma survey in mean levels of perceived gain | No differences between trauma and nontrauma survey in mean levels of regret | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Sikweyiya and Jewkes23 (2012) | Childhood emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, physical and sexual IPV, sexual harassment, domestic violence | Some reported pain, but it was short lived and not overwhelming | Majority reported positive affect | No regret | Victims reported that the experience was positive | Authors did not report on perpetrators’ risk of harm separately from victims’ risk of harm | Men reported discomfort; women reported feeling empoweredc | NR |

| DePrince and Freyd24 (2004) | Physical and sexual abuse | Mean scores on a 5-point scale (neutral to distress) | Most thought the research was important; importance was rated greater than distress | NR | All subgroups thought the research was important | NR | Women in subgroups 1d and 2e thought that it was a good idea to include such a measure in psychology; men in subgroup 2 reported that the questions were less distressing than daily life; women reported that the research was important for psychologists | NR |

| Schwerdtfeger and Goff25 (2008) | Child and adult abuse, rape | NR | Victims reported favorable reactions | NR | Victims of higher (vs lower) levels of abuse reported that the study was personally meaningful; no differences between groups in emotionality, insight, or discomfort | NR | NR | NR |

| Carter-Visscher et al.27 (2007) | Assessment 1: childhood physical and sexual abuse. Assessment 2: unrelated to childhood trauma. Assessment 3: 1-week follow-up | Low levels of distress over all 3 sessions | Assessment 1: 100% reported that research participation was somewhat interesting. Assessments 2 and 3: 95% reported that participation was somewhat interesting |

Assessment 1: no regret. Assessment 2: 4% reported regret. Assessment 3: 6% reported regret |

Victims of higher (vs lower) levels of childhood physical and sexual abuse of abuse) reported that the study had an “impact”f; no differences between groups with respect to willingness to take part and benefits | NR | NR | NR |

| Rojas and Kinder28 (2007) | Childhood sexual abuse | NR | NR | NR | No differences between victims in anxiety, anger, or depression | NR | No differences in adverse effects | NR |

| Ruzek and Zatzick29 (2000) | Physical assault/abuse, rape, molestation, child neglect | 12% reported unexpected upset; 32% reported negative reactions; 30% reported unwanted thoughts | 95% reported that benefits outweighed costs; 75% reported positive experience | 95% reported no regret | No differences in combined types of abuse in negative and positive responders | NR | No differences in combined types of abuse in negative and positive responders | Older participants reported being unexpectedly upset |

| Johnson and Benight30 (2003) | Domestic violence | 25% reported unexpected upset | 45% reported positive gains | 6% reported regret | Domestic violence victims reported being upset | NR | NR | NR |

| Newman et al.31 (2008) | Various forms of family violence, sexual assault, and sexual harassment | NR | NR | NR | No differences in personal satisfaction, personal benefits, emotional reactions, perceived drawbacks, or global evaluations | NR | Men reported that the experience was positive | NR |

| Savell et al.32 (2006) | Childhood sexual abuse | NR | NR | NR | No differences among victims in anxiety, anger, depression, or curiosity | NR | NR | NR |

| Campbell et al.34 (2010) | Rape, assault | 4.3% reported the experience as negative | Vast majority reported positive experience | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Edwards et al.37 (2012) | Child, adolescent, and adulthood abuse, rape, or domestic violence | 4.3% reported negative emotional reactions (baseline); 0% reported distress (2-month follow-up) | 23.3% reported personal benefits at baseline; 19% reported personal benefits at follow-up | NR | Childhood psychological abuse/neglect and childhood physical abuse victims reported distress; no differences in reports of distress between sexual abuse victims and those exposed to domestic violence | Perpetrators of adolescent and adulthood physical, sexual, and psychological IPV reported distress | NR | NR |

| Hlavka et al.38 (2007) | Verbal, psychological, physical, and sexual childhood and adulthood abuse | 44% of childhood sexual abuse victims did not complete the interview; 56% of childhood and adult victims did not complete the interview | 12% of childhood sexual abuse victims completed the interview; 33% of child and adult victims completed the interview | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Shorey et al.39 (2013) | Childhood emotional, physical, and sexual abuse; relationship aggression: psychological, physical, and sexual aggression, dating violence | Emotional reactions (mean = 13.53; SD = 4.51); perceived drawbacks (mean = 19.95; SD = 5.04) | Personal benefits (mean = 15.01; SD = 4.66) | NR | No differences in personal satisfaction, personal benefits, emotional reactions, perceived drawbacks, or global evaluations among victims of childhood emotional and physical abuse, psychological and sexual abuse, and dating violence; childhood sexual abuse victims reported negative emotional reactions and perceived drawbacks; physical aggression victims reported negative perceived drawbacks |

NR | NR | NR |

| Shorey et al.40 (2011) | Relationship aggression: psychological, physical, and sexual aggression, dating violence | Men: emotional reactions (mean = 15.39; SD = 3.54); perceived drawbacks (mean = 21.54; SD = 4.38) Women: emotional reactions (mean = 15.36; SD = 4.17); perceived drawbacks (mean = 21.61; SD = 5.41) |

Men: personal benefits (mean = 12.66; SD = 3.59) Women: personal benefits (mean = 12.52; SD = 3.77) |

NR | No differences in personal satisfaction, personal benefits, emotional reactions, perceived drawbacks, or global evaluations among women who experienced dating violence; female physical aggression victims perceived drawbacks; Male psychological and physical aggression victims reported personal benefits and marginally more emotional reactions | Female physical aggression perpetrators reported personal benefits; female sexual aggression perpetrators reported perceived drawbacks; male psychological and physical aggression perpetrators reported personal benefits and marginally more emotional reactions; male sexual aggression nonperpetrators reported perceived drawbacks | NR | NR |

| Edwards et al.41 (2013) | Childhood, adolescent, and adulthood psychological, physical, and sexual abuse, domestic violence | 7.7% reported negative emotional reactions (baseline); 2.1% reported distress (2-month follow-up) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence; NR = not reported. Studies are arranged by date in ascending order (details of all studies are presented in Tables S3 and S4). Values are the percentages of participants reporting, or mean levels of, benefit, harm, and regret (or other indicators of harm, benefit, or regret such as assessment completion). Unless specified, all reports were assessed during or immediately after study completion.

ICARIS-2 Injury and Control Risk Survey (a national, cross-sectional random-digit-dialing telephone survey of English- and Spanish-speaking adults).

SIPV pilot study (an annual telephone survey).

This was a qualitative study and male and female participants were not directly compared.

Undergraduate students.

Community members.

Impact was not defined by the authors.

RESULTS

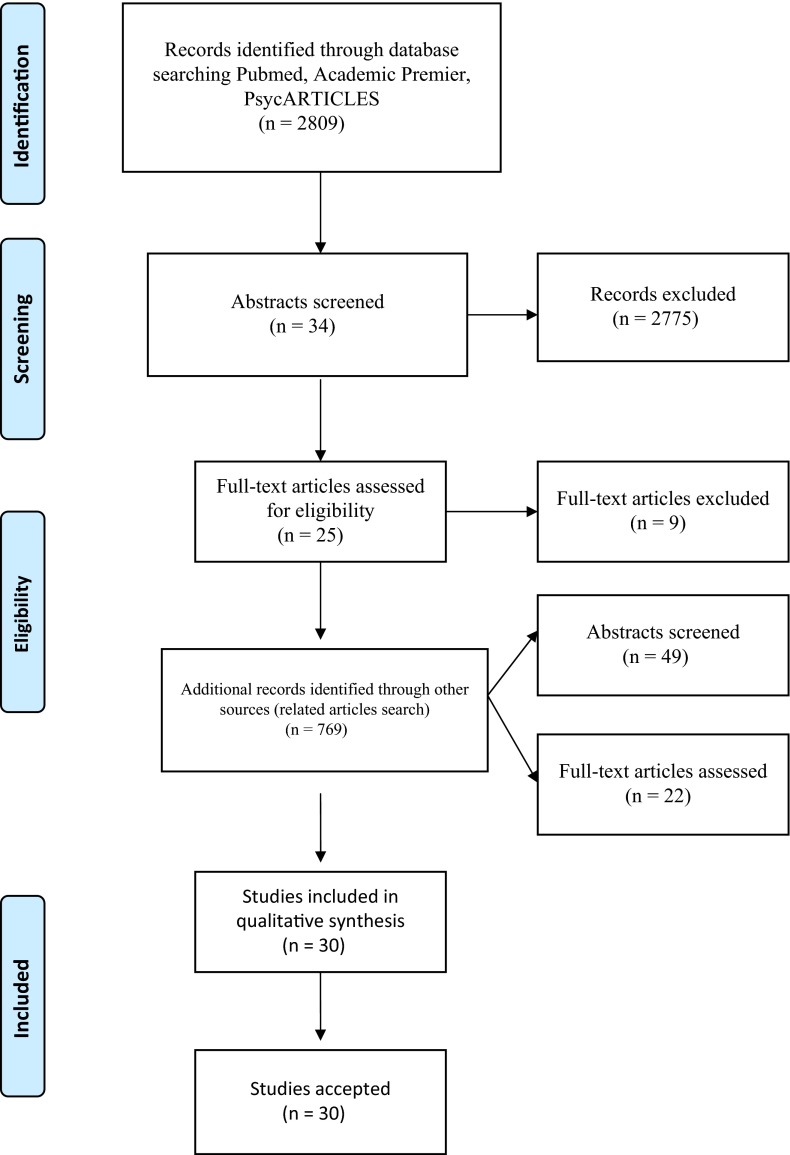

We identified 2809 articles through our search (Figure 1). The titles of these articles were assessed for relevance, and 34 were judged to be potentially relevant; in these cases, the abstract was assessed for possible inclusion. Twenty-five of the abstracts indicated that the studies were possibly relevant, and we obtained the full articles. A review of these 25 articles showed that 15 met the inclusion criteria, and these articles were included in our study. These 15 articles were then used to conduct a related-articles search that produced 769 additional articles (Figure 1). Using the same selection process, we included 15 of these articles in the study. Therefore, in total 30 articles were included in our review,11–18,20–41 4 involving adolescent participants and 26 predominantly involving adult participants. Of the 17 adult studies that reported participants’ age ranges, 14 included young adults between the ages of 18 and 19 years. Two of these studies included adolescents as young as 14 years. However, the proportion of the sample that was made up of adolescents was not reported in any of these studies, and we were not able to disaggregate the findings by age.

FIGURE 1—

Flow diagram of studies included in the review.

Of the 30 studies, 25 were conducted in North America, 2 in the United Kingdom, 1 in the Netherlands, 1 in Sweden and Estonia, and 1 in South Africa. They were published between 1997 and 2013. Four of the studies were conducted among adolescents and 26 among adults (Table 1; Tables S3 and S4).

Study Designs

Twenty-seven of the studies were quantitative (all 4 adolescent studies and 23 of the 26 adult studies), and 3 were qualitative. The quantitative studies were predominantly cross sectional (2 adolescent studies 16 adult studies). Six involved longitudinal designs (1 adolescent study and 5 adult studies), and the follow-up period in these studies ranged from 1 week to 13 months. Three of the 23 adult quantitative studies involved an experimental design (1 nonrandomized controlled trial20 and 2 randomized controlled trials21,22). Two adult studies made use of a combination of qualitative and quantitative designs.13,23

Measures Used

Exposure to violence and abuse or symptoms of traumatic events such as PTSD was assessed through questionnaires administered to respondents (2 adolescent and 16 adult studies), interviews (2 adolescent and 7 adult studies), or a combination of measures (3 adult studies). The types of violence measured varied across studies and included IPV (2 adult studies) and verbal, physical, or sexual violence (3 adolescent and 23 adult studies). Most of the studies focused on victimization, but 2 adolescent and 3 adult studies also included measures of perpetration. Eight studies (all among adults) measured symptoms of exposure to violence (PTSD). In addition to measuring interpersonal violence, 5 studies also measured noninterpersonal violence (e.g., motor vehicle accidents, combat, medical traumas, natural disasters).

In some studies, existing scales, including the Brief Betrayal Trauma Survey,20,24 the Trauma Symptom Checklist-40,20,21,25 the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire,13,17,18,26,27 the Child Sexual Experience Scale,28 and the Traumatic Events Questionnaire,25,29 were used to measure exposure variables. Other studies included questions designed by the study authors (Tables S3 and S4).

The outcomes of interest (harms, benefits, and regrets resulting from research participation) were measured via questionnaires (2 adolescent and 17 adult studies) and interviews (2 adolescent and 9 adult studies). In different studies, outcome variables included measures of harm (4 adolescent and 19 adult studies), benefit (17 adult studies), and regret (8 adult studies). Again, some studies incorporated existing scales to measure outcome variables, such as the Reactions to Research Participation Questionnaire for Children,20,21,25,29–31 the State-Trait Personality Inventory,21,28,32 and the Injury and Control Risk Survey.11 Other studies included questions designed by the study authors. One longitudinal study measured dropout at follow-up as an indicator of harm.33

All 4 adolescent studies and 18 adult studies included comparisons between participants who had been victims of abuse and those who had not. One adolescent study and 2 adult studies reported on comparisons between participants who had been perpetrators of abuse and those who had not. Two of the adolescent studies and 8 of the adult studies compared male and female participants’ reactions to research participation. Finally, 1 adolescent study and 2 adult studies compared older participants with younger ones with respect to reporting of harms or benefits.

Risk of Bias

The risk of bias assessment classified 66.7% of studies as weak, indicating that they were at high risk of bias and that caution should be applied in interpreting the findings. Among the adolescent studies, 2 of the 4 quantitative studies were rated as weak and 2 as moderately weak (Table S5, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Of the 23 quantitative adult studies, 15 were rated as weak, 7 as moderately weak, and 1 as strong (Table S6, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Factors contributing to weak ratings were absence of adequate descriptions of sampling (1 adolescent and 21 adult studies), absence of evidence of the reliability and validity of both the exposure and outcome measures (2 adolescent and 3 adult studies), and cross-sectional study designs (2 adolescent and 15 adult studies; Tables S5 and S6).

Ten (1 adolescent and 9 adult) studies were either experimental or longitudinal investigations. None of these 10 studies included descriptions of efforts to ensure blinding, and thus these investigations were assigned a rating of 2 (moderate risk of bias) in our blinding assessment. Five of the 10 studies reported more than 80% completion rates and therefore received a strong rating with respect to withdrawal and dropout (low risk of bias). One study reported that 77.2% of participants returned for the follow-up, and this study received a moderate risk of bias rating. The other 4 studies did not report on their withdrawal or dropout rate and thus were classified as weak.

We judged one of the 3 qualitative studies as having no or few flaws34 and the other 2 studies as having some flaws that were unlikely to affect study validity.14,23 The main area of weakness was sampling; one study offered a description of the sampling procedure but no rationale for using this method, and the other did not mention the sampling procedure at all (Table S7, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Adolescent Studies

A synthesis of the results from the adolescent studies is presented in Table 1. All 4 of the adolescent studies measured reports of harm only and did not assess whether participants found their research experience beneficial or had any regrets about participating. In these studies, the percentage of participants reporting harm ranged from low (2.5%26) to moderate (37%35), with a median percentage of 5.7%.33 These studies had different indicators for harm (e.g., being upset,26,36 feeling discomfort,35 and finding the questions distressing33).

All 4 adolescent studies included a comparison of the research experience of those with and without a history of abuse victimization. In 3 of the 4 studies, the participants with a history of abuse reported more harm as a result of research participation than those without such histories.26,33,35 The topics of these 3 studies were suicidal behavior, physical and sexual abuse, and drug use26; sexual abuse victimization and perpetration, sexual attitudes, and pornography35; and physical and sexual assault or abuse, witnessing of community and parental violence, and experience of other traumatic events (PTSD, major depression, and alcohol abuse).33

In the study in which there were no significant differences in reported harms36 between participants with and without a history of abuse victimization, the questions focused on victimization and perpetration of verbal, physical, and sexual abuse.36 Two of the adolescent studies included questions about perpetration of violence; however, one did not report on the perpetrator’s harm separately from the victim’s harm, so there is no way to determine which percentage of perpetrators were at risk for harm and which percentage of victims were at risk for harm.35 The results of the other study showed that perpetrators were no more likely than nonperpetrators to be at risk of harm.36

Three of the 4 adolescent studies measured gender differences in responses to research participation, and 2 of these investigations showed that girls experienced more harms than boys.33,36 In one of these studies, 7.5% of girls and 3.9% of boys reported harm (P = .001)33; in the other study, the prevalence was not reported.36 In the third study, there was no difference in reports of harm between girls and boys, but girls were more interested in the survey content than boys.26

The single adolescent study that investigated whether there were age differences in reports of harm resulting from study participation revealed that younger adolescents (10–12 years of age) were more likely to experience harm than older adolescents (13–15 years of age) in research focusing on verbal, physical, or sexual abuse victimization and perpetration.36 The prevalence of reported harm in the respective age groups was not reported.

Only 2 adolescent studies33,36 provided evidence on longer-term effects (with a 12–13-month follow-up). In one of the studies, participants did not report more harm at follow-up than at baseline.36 In the other study, those who were upset at baseline were no more likely than their counterparts to drop out of the study.33

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess the validity of our results. The findings showed that if we were to exclude the 2 adolescent studies26,35 at high risk of bias, the review conclusions based on the remaining 2 adolescent studies33,36 would be unchanged.

Adult Studies

Table 1 presents a synthesis of the findings of the adult studies. Harms and benefits were assessed in a variety of ways. Harms were indicated by unexpected upset, negative reactions or emotions, unwanted thoughts, distress, bother, or drawbacks. Benefit was indicated by positive experiences or feelings about participation; gaining something positive from participation; perceptions that participation was interesting, enjoyable, beneficial, useful, or satisfying; a belief that these types of questions should be asked; reports that the research environment was supportive; and reports that participation was instrumental in creating new ways of interpreting participants’ experiences as survivors. Regret was measured by participants’ level of willingness to take part in the research again if they had known what participation would have been like.

The percentage of participants reporting harm ranged from 4.3%37 to 50%,14 with a median of 25%. The percentage of participants reporting benefits ranged between 23.3%37 and 100%14,27 with a median of 92.4%. Finally, the percentage of participants reporting regret ranged from 0.09%17 to 6%,27,30 with a median of 2%.

One study compared reactions to research participation by administering a survey focusing on trauma to half of the participants and a survey that did not focus on trauma to the other half; this study did not measure the prevalence of harm or benefit.22 In a randomized controlled trial, Ferrier-Auerbach et al.22 found that those administered the trauma survey reported being more upset than those administered the nontrauma survey. They also found that there were no differences between the 2 groups in ratings of perceived gain from participating in the study or regret, as measured by willingness to complete the research if they had known ahead of time what completion of the questionnaire would have been like. In another study, noncompletion of the interview was used as an indicator of harm.38 In this study, 44% of childhood sexual abuse victims and 56% of childhood and adult victims of violence did not complete the interview.

In 18 (95%) of the 19 adult studies that measured both participant-reported harms and benefits, a greater proportion of participants reported benefits than harm. In the study with the highest reported level of harm (50%),14 all of the participants reported benefits. In the study with the lowest reported level of benefit (23.3%),37 only 4.3% of participants reported immediate negative emotional reactions, and none reported other harms 2 months after completing the study questionnaire. In the studies with the highest level of reported regret (6%), a high percentage of participants reported benefits (45%30 and 95%27). In only one study was the reported prevalence of harm greater than the reported prevalence of benefits.11 In this study, 70% of participants reported low levels of harm, with most saying that they were either somewhat upset or not upset at all, and 51% found participation to be at least somewhat useful.

In one adult study, interview noncompletion rates were used as an indicator of harm.38 The results showed that participants who reported penetrative childhood sexual abuse were much more likely not to complete the interview than those who did not report abuse, indicating that these participants were possibly at risk for harm. However, there were no differences in interview completion rates between victims and nonvictims of severe childhood physical abuse and adult IPV and nonpartner violence.

The single qualitative study, in which participants were interviewed about their participation via questions about male IPV victimization and perpetration, did not report perpetration results separately from victimization results but instead provided overall narrative responses.23 Participants in this study who had been victims of violence and abuse reported that the survey caused them to relive their experiences, making them sad and leading to experiences of pain at the time of survey completion. However, no participants believed that the survey was emotionally harmful, none believed that they needed professional support because of the questions asked, and the majority believed that they benefited from survey participation and did not regret taking part.

Five of the 10 studies that compared harms between victims and nonvictims showed that victims reported more harm, and 5 showed no difference. In 6 (86%) of the 7 studies that compared harms between participants with and without PTSD symptoms, those with symptoms reported research participation to be more harmful than those who did not have symptoms12,15,17,20,27,29; in the remaining study, there were no significant differences between these groups.31

Three (43%) of the 7 studies that compared benefits between victims and nonvictims showed that victims reported more benefits; in the other 4 studies, there were no differences. Two studies compared benefits between participants with and without PTSD symptoms. In one of these studies, participants who indicated that research participation was personally meaningful reported higher levels of PTSD symptoms than those who indicated that participation was not personally meaningful.26 The other study did not reveal any significant differences in reported benefits between those with and without PTSD.31 None of the studies compared reports of regrets among victims and nonvictims. One study compared participants with higher levels of PTSD and those with lower levels and showed that those in the former group reported less regret.

Three studies37,39,40 compared the effects of sensitive research on victims and nonvictims of different types of violence. No matter the type of violence, victims reported either more harm or benefit (6 subgroups) than nonvictims or there was no difference between victims and nonvictims (3 subgroups). There were no instances of victims reporting fewer harms or benefits than nonvictims.

Only 3 adult studies asked about perpetration of violence. One of these studies did not report on perpetrators’ risk of harm separately from victims’ risk,23 and one37 showed that perpetrators reported more harm than nonperpetrators. The other study compared the effects of sensitive research on perpetrators and nonperpetrators of different types of violence. In 3 subgroups perpetrators reported more harm and benefit than nonperpetrators, and in 1 subgroup perpetrators reported less harm than nonperpetrators.40

Eight studies investigated gender differences in experiences related to research participation, and 6 (75%) of these investigations showed that there were gender differences in reported levels of harm and benefit. In 3 of the 6 studies, women were more upset by participation than men.11,16,31 In the other 3 studies, women reported more positive experiences and men reported more negative experiences.20,23,24

In all 3 studies investigating the association between age and research experience, older participants were significantly more likely than younger participants to report harm (being more upset than expected).16,20,29 In one of these studies, older participants were also more likely to report greater benefit than younger participants.20 None of the studies measuring regret assessed age differences.

Only 3 (12%) adult studies17,37,41 provided evidence of longer-term effects. All 3 had a very short follow-up period ranging from 48 hours17 to 2 months.37,41 In one of these studies, participants did not report more harm at follow-up, and those who were upset at baseline were no more likely than their counterparts to drop out of the study.17 In the second study, 2.1% of participants reported harm after a 2-month follow-up as a result of their participation.41 In the third study, no participants reported harm at 2 months, but those with a history of abuse were less likely to return for follow-up.37

Again, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess the validity of our results. In this analysis excluding the 18 (69%) adult studies at high risk of bias, the review conclusions we would make on the basis of the remaining 8 studies13,17,18,21,22,37,38,41 were somewhat different. The percentages of participants reporting harm decreased from a range of 4.3% to 50% to a range of 4.3% to 13%. None of the 8 studies included in the sensitivity analysis compared victims’ and nonvictims’ reports of benefits. Our results regarding reports of harm among victims and nonvictims would be based on fewer studies but would be unchanged. None of the 8 studies included a comparison of gender and age with regard to research experience.

DISCUSSION

Self-reports are often the most efficient data collection method in research on violence and abuse; however, collection of this information necessitates that research participants respond to sensitive, potentially traumatizing questions.2 The main goal of ethical committees and institutional review boards is to ensure the safety of participants during research. It is therefore important to investigate participants’ experience of research that includes questions about violence and abuse. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that has examined participants’ experiences of being surveyed about these topics.

Adolescent Studies

Research on the potential harms and benefits of adolescents’ participation in research on violence and abuse appears to be in its infancy. We identified only 4 such studies, and none reported on benefits and regrets, making it impossible to compute a risk–benefit ratio. Reports of harm were relatively low (2.5%–23% of participants). The study with the lowest prevalence of reported harm (2.5%–7.5%)26 involved an interviewer-administered questionnaire. It is possible that adolescents underreported harm given the face-to-face nature of the interaction. In the study with the highest prevalence (36%) of reported harm,35 the questions had a stronger focus on sex and sexual abuse than the other adolescent studies. The questions covered sexual attitudes, pornography, and sexual abuse victimization and perpetration. The combination of these topics might elicit particularly strong feelings of discomfort and other potential harm.

In 3 of the 4 adolescent studies, those with a history of abuse reported more harm than those without such a history. The participants in these 3 studies were older (12–18 years of age) than the participants in the other study (10–15 years of age), in which no significant differences were found. This might suggest that younger adolescents do not find talking about their traumatic history upsetting because they have not yet realized the magnitude of what they have experienced.

In an exception to this trend, one adolescent study that investigated age and research experience showed that younger adolescents (10–12 years of age) were more likely to report being upset than older adolescents (13–15 years of age).36 However, it is important to note that most of the younger participants in this research completed the study survey while being monitored by their caregivers. The researchers suggested that these younger adolescents thus may have felt upset and that their privacy was being violated.36

Only one study looked at perpetration of abuse, and the results showed no differences between perpetrators and nonperpetrators with respect to reports of harm. Future research needs to include an increased focus on perpetrators of violence and abuse. Our review of the 3 studies that reported gender differences in research experience supported our prediction that female participants are more likely to report harm than male participants. The single study that compared the harms experienced by younger and older adolescents supported our hypothesis that younger participants would report more harm.

Adult Studies

Considerably more research has been conducted on the potential harmful effects of research participation among adults than adolescents. In 95% of the 19 studies measuring both harms and benefits, participants reported a greater prevalence of benefit than harm. Although these results indicate that reports of benefits are more prevalent than reports of harms, they do not provide an indication of severity of harm. Clearly, this needs to be an important focus of future research. Very few (38%) studies asked whether participants had regrets about taking part in the research, and this too needs to be addressed in future research.

An assessment of possible reasons for the distribution of harm and benefit levels between studies showed that participant category and prior traumatic experiences had a clear impact on the experience of research participation. Studies in which the prevalence of reported harm was above the 25% median were those in which the population was limited to people who had traumatic experiences prior to their participation, such as domestic violence survivors,15,30 hospitalized victims of assaults or motor vehicle accidents,29 psychiatric patients,12 and those bereaved by homicide.14 The studies in which the prevalence of reported harm was below the 25% median were those in which the sample was not limited to people with prior traumatic experiences but rather included health maintenance organization members,17,18 sexually experienced people,16 undergraduate students,13,27,37,41 and community members11 (with the exception of one study in which participants had been rape survivors34). These results reinforce our finding that victims report more harm than nonvictims. The types of questions participants were asked did not appear to affect study-specific variations in the prevalence of reported harms and benefits.

We found a reasonably consistent pattern of victims being more affected than nonvictims by research on abuse. Most of the studies that compared reports of harm between victims and nonvictims showed that victims reported more harm. Of the 7 studies that compared reports of benefits between victims and nonvictims, 3 showed that victims were more likely to report benefiting from the research than nonvictims. In the other 4 studies, there were no differences between groups. An assessment of potential reasons for the differences in research experiences between participants with and without a history of abuse did not show any major differences in study design or the content of the questions asked, with all studies asking similar questions about past abuse.

Surprisingly few studies compared the effects on perpetrators of violence with the effects on nonperpetrators; those that did showed no differences between perpetrators’ and nonperpetrators’ research experience. Further studies are needed on perpetrators’ experience of participating in research that asks about abuse.

Given that gender norms and power differentials are associated with violence, it was unexpected that only 8 (31%) studies compared the experiences of men and women. These studies produced conflicting results, which does not support our initial prediction. Women do not necessarily report more harm than men, and men are likely to be more distressed than women by sensitive research. In all 3 of the adult studies investigating age differences, older participants were significantly more likely than younger participants to report harm.

Limitations

The limitations in the original studies also represent limitations of this review. Harm and benefit were defined differently in different studies, suggesting the need for a more standardized approach to measurement. Most of the original studies were judged to be at high risk of bias, indicating the need for better quality studies. We were not able to consider potential confounders such as the age at which the violence was experienced and the time between the violence and research participation. These confounders were rarely taken into account in the included studies.

Furthermore, we were not able to assess participants’ longer-term reactions to research participation because most studies assessed reactions to the research at the same time or immediately after participation. Participants asked to disclose abuse victimization could be at risk of being revictimized by the perpetrators as punishment for disclosing abuse-related information. We searched the included studies for evidence related to revictimization and found only one study in which some of the participants, after disclosing abuse, reported being fearful that their partners would find out and become violent.23 This is an important question for future studies.

Conclusions

Research on sensitive topics such as abuse and violence (including IPV) is extremely important to generate an appropriate and balanced understanding of risk factors and the most helpful interventions to address this global public health concern.6,7 Research on these topics can lead to treatment and support for survivors, as well as interventions that can prevent future abuse and violence.

However, there has been growing recognition that research on sensitive topics may involve benefits (such as relief and a sense of sharing and being listened to) as well as harms (including minor upset, significant distress, and retraumatization). Thus, in every research study, ethical considerations must be made (typically by research teams and ethics review boards) about the risk–benefit ratio of the project. Empirical support for risk–benefit assessments in sensitive research involving human participants is surprisingly limited but potentially crucial to help research and ethics teams make judgments regarding proposed projects. An overemphasis on risks may lead to avoidance of sensitive but important research; an underrecognition of potential harm may reduce mindfulness of the impact of sensitive research on participants.

Our findings support the importance of continuing to conduct research on sensitive topics such as abuse and violence. Our results suggested that although there were reports of discomfort, upset, and other negative emotions, reports of benefits also accompanied research participation. In spite of the theoretical risk of retraumatization, the majority of articles reviewed indicated that the risk–benefit ratio related to asking sensitive questions regarding trauma and abuse was not unfavorable. Although there have not been many studies investigating regrets associated with participation in sensitive research, the limited evidence on regrets suggests that, in spite of the sensitive nature of the research, almost all participants do not regret taking part.

Our findings also support the need for continuing to assess the impact on participants of research on sensitive topics such as abuse and violence. We have been able to describe the prevalence of reports of risks and benefits and the risk–benefit prevalence ratio. Future longitudinal research needs to address issues we know little about, including severity of harm, revictimization as a consequence of research participation, and the effects of participation on perpetrators of violence and abuse.

Acknowledgments

The full title of the project is “Promoting Sexual and Reproductive Health Among Adolescents in Southern and Eastern Africa—Mobilising Schools, Parents and Communities” (PREPARE). The PREPARE study is funded by the EC Health research programme (under the 7th Framework Programme; grant Agreement number: 241945). The partners and principal investigators include: University of Cape Town (Cathy Mathews), Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (Sylvia Kaaya), University of Limpopo (Hans Onya), Makerere University (Anne Katahoire), Maastricht University (Hein de Vries), University of Exeter (Charles Abraham), University of Oslo (Knut-Inge Klepp), University of Bergen (Leif Edvard Aarø; coordinator).

We would like to express our gratitude to the members of the PREPARE Scientific Advisory Committee: Nancy Darling, Oberlin College, Ohio; Jane Ferguson, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland; Eleanor Maticka-Tyndale, University of Windsor, Ontario; and David Ross, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK. We are indebted to the school staff and adolescents for their participation in this study. (See also the project homepage http://prepare.b.uib.no.)

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was needed because this was a review of already-published secondary data.

References

- 1.Rosenbaum AF, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J. Meta-research on violence and victims: the impact of data collection methods on findings and participants. Violence Vict. 2006;21(4):404–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tourangeau R, Smith TW. Asking sensitive questions: the impact of data collection mode, question format, and question context. Public Opin Q. 1996;60(2):275–304. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rose S, Bisson J, Churchill R, Wessely S. Psychological debriefing for preventing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(3):CD000560. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nader K, Hardt O. A single standard for memory: the case for reconsolidation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(3):224–234. doi: 10.1038/nrn2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newman E, Kaloupek DG. The risks and benefits of participating in trauma-focused research studies. J Trauma Stress. 2004;17(5):383–394. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000048951.02568.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Black MC, Black RS. A public health perspective on “the ethics of asking and not asking about abuse.”. Am Psychol. 2007;62(4):328–329. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X62.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker-Blease K, Freyd JJ. Research participants telling the truth about their lives: the ethics of asking and not asking about abuse. Am Psychol. 2006;61(3):218–226. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.3.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahern K. Informed consent: are researchers accurately representing risks and benefits? Scand J Caring Sci. 2012;26(4):671–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ullman SE. Asking research participants about trauma and abuse. Am Psychol. 2007;62(4):329–330. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Draucker CB. The emotional impact of sexual violence research on participants. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1999;13(4):161–169. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(99)80002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Black MC, Kresnow M, Simon TR, Arias I, Shelley G. Telephone survey respondents’ reactions to questions regarding interpersonal violence. Violence Vict. 2006;21(4):445–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlson EB, Newman E, Daniels JW, Armstrong J, Roth D, Loewenstein R. Distress in response to and perceived usefulness of trauma research interviews. J Trauma Dissociation. 2003;4(2):131–142. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Decker SE, Naugle AE, Carter-Visscher R, Bell K, Seifert A. Ethical issues in research on sensitive topics: participants’ experiences of distress and benefit. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2011;6(3):55–64. doi: 10.1525/jer.2011.6.3.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gekoski A, Gray JM, Adler JR. Interviewing women bereaved by homicide: assessing the impact of trauma-focused research. Psychol Crime Law. 2012;18(2):177–189. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffin MG, Resick PA, Waldrop AE, Mechanic MB. Participation in trauma research: is there evidence of harm? J Trauma Stress. 2003;16(3):221–227. doi: 10.1023/A:1023735821900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuyper L, de Wit JF, Adam PF, Woertman L. Doing more good than harm? The effects of participation in sex research on young people in the Netherlands. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41(2):497–506. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9780-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newman E, Walker EA, Gefland A. Assessing the ethical costs and benefits of trauma-focused research. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1999;21(3):187–196. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(99)00011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker E, Newman EF, Koss MF, Bernstein D. Does the study of victimization revictimize the victims? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1997;19(6):403–410. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(97)00061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh D, Downe S. Appraising the quality of qualitative research. Midwifery. 2006;22(2):108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DePrince AP, Chu A. Perceived benefits in trauma research: examining methodological and individual difference factors in responses to research participation. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2008;3(1):35–47. doi: 10.1525/jer.2008.3.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cook SL, Darnell D, Anthony ER et al. Investigating the effects of trauma-related research on well-being. Account Res. 2011;18(5):297–322. doi: 10.1080/08989621.2011.584772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrier-Auerbach AG, Erbes C, Polusny MA. Does trauma survey research cause more distress than other types of survey research? J Trauma Stress. 2009;22(4):320–323. doi: 10.1002/jts.20416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sikweyiya YF, Jewkes R. Perceptions and experiences of research participants on gender-based violence community based survey: implications for ethical guidelines. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DePrince AP, Freyd JJ. Costs and benefits of being asked about trauma history. J Trauma Pract. 2004;3(4):24–35. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwerdtfeger KL, Goff BS. The effects of trauma-focused research on pregnant female participants. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2008;3(1):59–67. doi: 10.1525/jer.2008.3.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langhinrichsen-Rohling JF, Arata CF, O’Brien NF, Bowers DF, Klibert J. Sensitive research with adolescents: just how upsetting are self-report surveys anyway? Violence Vict. 2006;21(4):425–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carter-Visscher RM, Naugle AE, Bell KM, Suvak MK. Ethics of asking trauma-related questions and exposing participants to arousal-inducing stimuli. J Trauma Dissociation. 2007;8(3):27–55. doi: 10.1300/J229v08n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rojas A, Kinder BN. Effects of completing sexual questionnaires in males and females with histories of childhood sexual abuse: implications for institutional review boards. J Sex Marital Ther. 2007;33(3):193–201. doi: 10.1080/00926230701267795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruzek JI, Zatzick DF. Ethical considerations in research participation among acutely injured trauma survivors: an empirical investigation. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000;22(1):27–36. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(99)00041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson LE, Benight CC. Effects of trauma-focused research on recent domestic violence survivors. J Trauma Stress. 2003;16(6):567–571. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000004080.50361.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newman EF, Willard TF, Sinclair RF, Kaloupek D. Empirically supported ethical research practice: the costs and benefits of research from the participants’ view. Account Res. 2008;8(4):309–329. doi: 10.1080/08989620108573983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Savell JK, Kinder BN, Young MS. Effects of administering sexually explicit questionnaires on anger, anxiety, and depression in sexually abused and non-abused females: implications for risk assessment. J Sex Marital Ther. 2006;32(2):161–172. doi: 10.1080/00926230500442326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zajac K, Ruggiero KJ, Smith DW, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. Adolescent distress in traumatic stress research: data from the National Survey of Adolescents-Replication. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24(2):226–229. doi: 10.1002/jts.20621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell R, Adams AE, Wasco SM, Ahrens CE, Sefl T. “What has it been like for you to talk with me today?”: the impact of participating in interview research on rape survivors. Violence Against Women. 2010;16(1):60–83. doi: 10.1177/1077801209353576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Priebe G, Backstrom MF, Ainsaar M. Vulnerable adolescent participants’ experience in surveys on sexuality and sexual abuse: ethical aspects. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34(6):438–447. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ybarra ML, Langhinrichsen-Rohling JF, Friend JF, Diener-West M. Impact of asking sensitive questions about violence to children and adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(5):499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edwards KM, Gidycz CA, Desai AD. Men’s reactions to participating in interpersonal violence research. J Interpers Violence. 2012;27(18):3683–3700. doi: 10.1177/0886260512447576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hlavka HR, Kruttschnitt C, Carbone-López KC. Revictimizing the victims? J Interpers Violence. 2007;22(7):894–920. doi: 10.1177/0886260507301332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shorey RC, Zucosky H, Febres J, Brasfield H, Stuart GL. Males’ reactions to participating in research on dating violence victimization and childhood abuse. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2013;22(4):348–364. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2013.775987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shorey RC, Cornelius TL, Bell KM. Reactions to participating in dating violence research: are our questions distressing participants? J Interpers Violence. 2011;26(14):2890–2907. doi: 10.1177/0886260510390956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edwards KM, Probst DR, Tansill EC, Gidycz CA. Women’s reactions to interpersonal violence research: a longitudinal study. J Interpers Violence. 2013;28(2):254–272. doi: 10.1177/0886260512454721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]