Abstract

Using a social–ecological framework, we drew on a targeted literature review and historical and contemporary cases from the US labor movement to illustrate how unions address physical and psychosocial conditions of work and the underlying inequalities and social determinants of health. We reviewed labor involvement in tobacco cessation, hypertension control, and asthma, limiting articles to those in English published in peer-reviewed public health or medical journals from 1970 to 2013. More rigorous research is needed on potential pathways from union membership to health outcomes and the facilitators of and barriers to union–public health collaboration. Despite occasional challenges, public health professionals should increase their efforts to engage with unions as critical partners.

We need not look any further than Broad Street to understand that place matters.1,2 When physician John Snow strongly suspected that contaminated water from a local pump was causing the cholera epidemic in London in 1854, his use of maps and his storied removal of the pump handle became a potent symbol of the importance of intervening on the environmental level to prevent disease and improve health.3,4 More than a century later, a wealth of strong epidemiological evidence documents that health and environment—its physical, social, and economic conditions—are linked.5,6 Recent emphasis on this interaction may be traced to the 1986 Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, through which global health leaders called for international action to promote the health of all peoples by addressing how “health is created and lived by people within the settings of their everyday life.”7(p3) In public health’s increasingly place-based intervention model, the literature on place emphasizes sites in which we learn (e.g., schools), play (e.g., parks), and love (e.g., home). Ironically, however, although “work and health are intimately connected,”8(p101) outside the occupational health and safety literature, and with some notable exceptions,9–14 sites of work and workplace policies are seldom featured in public health efforts, nor are management and labor viewed as key actors. We argue that organized labor and the worksites, industries, and communities labor represents are and should be accorded greater consideration as critical and active participants in the public health arena.

With a steady decline in union membership over the past half century,15–18 mainstream media often elects to discuss unions as a relic of the past, and many political and government figures try to erase them from our collective memory.19,20 In stark contrast, we challenge the public health community to view unions as a vital part the past, present, and, most importantly, future public health infrastructure of the United States. Using the social–ecological model as a framework for analysis, we have used historical and contemporary efforts to illustrate how unions have helped create healthier workers, workplaces, and communities.

UNIONS YESTERDAY AND TODAY

Our labor unions are not narrow, self-seeking groups. They have raised wages, shortened hours, and provided supplemental benefits. Through collective bargaining and grievance procedures, they have brought justice and democracy to the shop floor.

–Senator John F. Kennedy21

While some trace the roots of contemporary unions to the guilds of medieval Europe and others to labor unrest of early European capitalism, unions are, in either case, far older than America.15,19 On our own shores, examples of workers organizing for change date back to Jamestown, Virginia, where in 1619 Polish craftsman halted work to demand the right to vote.19,20 Through changes in our nation’s social, political, and economic landscape, through wars and depressions, workers have risked their lives to improve living and working conditions.19,20,22,23 In 1935, with the signing into law of the National Labor Relations Act, workers gained the legal right

to self-organization . . . to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing and to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid and protection.24(p8)

For nearly 3 decades following the National Labor Relations Act’s passing, unions saw steady growth. By 1955, more than one third of US workers were in unions. Following the dramatic expansion of unions from the late 1930s to the 1950s, growth slowed in the 1960s and by the 1970s was in decline.20,25 Among the major contributors to this decline were the conservative resurgence of the 1970s, which created probusiness conditions in social and political spheres; the rise of corporate political organizing; the transition from a manufacturing to a nearly union-free service-based economy; the rapid dependence on contract work and growth of occupations in which the legal right to organize is absent; globalization of production; and the failure of US labor unions to evolve to meet these new demands.20,26–28 A recent study of more than 4000 low-wage workers in Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York City further found that although 1 in 5 reported having tried to form a union or made a complaint to their employer in the last year, fully 43.0% had suffered retaliation, such as wage cuts and suspensions, which has a chilling effect on organizing efforts.29 In 2012, the union membership rate was just 11.3%—a 97-year low.18

Although the number and proportion of unionized workers—private and public—is sharply down, unions remain a powerful force within the workplace and larger political sphere. A public health perspective, within the context of the social–ecological framework, may provide among the greatest evidence and clearest arguments for how unions continue to play a critical role in promoting the health of workers and the broader communities of which they are a part.

SOCIAL–ECOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK AND UNIONS

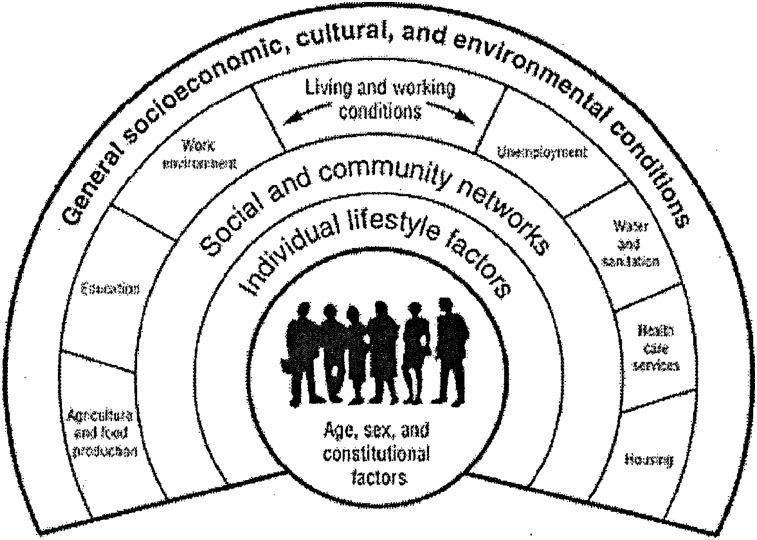

Although links between working conditions and worker health are well documented,8,9,22,30–32 the mechanisms by which unions build healthy workplaces and support healthy workers are not.33 Public health theory provides a road map for better understanding how unions keep our workforce and communities healthy. In particular, the social–ecological framework (Figure 1) holds considerable promise.34

FIGURE 1—

The social ecological framework.

Source. Dahlgren and Whitehead.34

Developed by Bronfenbrenner35 and expanded and refined by McLeroy,36 Stokols,37 Sallis,38 and others, the social–ecological model goes beyond the individual to focus on the broader sociostructural conditions and the full range of factors affecting worker health and well-being across levels of analysis. The social–ecological framework “recognizes the connection between health and social institutions, surroundings, and social relationships.”39(p1) By sharp contrast with individually focused approaches, it directs intervention attention to understanding and changing interpersonal, institutional, community, and public policy factors as mechanisms for supporting health.36,40 As Baron et al. point out, the social–ecological framework holds particular relevance for addressing health inequity in low-wage worker populations through workplace interventions because of the intimate interdependence between occupational and nonoccupational risk factors.10

The socioecological framework cannot be separated from the power relationships of the community and broader society.36 Like public health, the social–ecological framework recognizes how broad political economic structures affect the lives of individuals through an “unequal distribution of wealth, power, and life chances” by class, race/ethnicity, and other factors.41(p112–113) Additionally, the social–ecological framework emphasizes the need to recognize, and make use of, the reciprocal interactions between levels.42,43 Finally, some have argued that to fully benefit from an ecological approach to health, the community should be not only involved but also empowered in and through the research and intervention process.36,44,45

Through the ways unions are organized and operate, structural vulnerability—or the systemic production or patterning of suffering and exclusion that render certain groups at greater risk for social inequalities and health disparities46–48—is often addressed. There remains, of course, room for improvement, including with regard to continued, albeit lessened, gender inequities in union leadership.49,50 Despite their imperfections, however, unions often enable individual workers to change their relationships to their peers and promote changes in organizational and social processes as well. Further, workplace-level change may encourage, and sometimes even demand, changes in the larger community and policy arena. The union is uniquely situated to address inequalities in health by coordinating intervention at all levels of the ecological model while empowering workers and addressing the power inequalities at the heart of community health.

UNIONS AND THE HEALTH OF US WORKERS

The 40-hour work week, the minimum wage, family leave, health insurance, Social Security, Medicare, retirement plans. The cornerstones of the middle-class security all bear the union label.

—President Barack Obama51

Although labor’s earliest battles centered on health, responding to workplace injury, illness, and death, the broader public health community has been slow to explore the union’s impact on health. A recent study investigating the relationship between unionization and health in the workforce provides the first clear evidence of a positive association between union membership and self-rated health in a representative sample of 11 347 full-time workers.33 Hypothesizing income as a potential channel through which union membership affects self-rated health, the study found income to be a key, but not the sole, mechanism of the union–health relationship.33

The substantial literature now documenting that income and wealth, as indicators of economic status, are strongly associated with health outcomes underscores the importance of this finding.33,52–57 With few exceptions, adults’ quality of life cannot be separated from the wages they or their partners earn.54 Across the literature, union membership can be found to have a positive effect on wages.33 As Mishel and Walters have noted, “Unions raise the wages of unionized workers by roughly 20% and raise compensation, including wages and benefits, by about 28%.”58(p1) Additionally, when unions are strong it is not just union workers that benefit. By creating a higher prevailing wage, unions raise the income for nonunion workers as well, thus reducing wage inequality.58 Alternatively, when unions are weak, wages sink for everyone.28 Further, and although many factors contributed to the recent Great Recession,26 it is not incidental that the United States has seen the largest income inequality and wealth concentration since the Great Depression arise at a time when union density is at a record low.28

Wages are a major pathway through which unions contribute to improved health. But unions also address the physical, psychological, and social conditions of work while attacking the underlying inequalities and social determinants of health. Like higher income, safe workplaces, job security, and health care access share 2 traits in common: all are linked to favorable health and tend to be linked to union membership as well.31,33

Although unions are, by definition, most heavily focused on worker health and safety, they also have proven valuable (albeit sometimes less visible) partners in broader public health campaigns. In other instances, public health and union forces have sometimes worked in opposition, particularly with respect to early tobacco control measures, when the industry was often actively courting worker organizations.59–61

To understand this phenomenon further, we completed a literature review of 3 prominent public health issues—tobacco cessation, hypertension control, and asthma—and the union–health intersection. We undertook all searches using the search engine Google Scholar. Although search terms varied depending on the topic, we used the words “labor union” as a proxy for union or labor involvement, and we limited articles to those in English published in peer-reviewed public health or medical journals between the years 1970 and 2013.

Unions and Tobacco Control

Of the 145 peer-reviewed articles we identified that included the terms “smoking” or “tobacco” and “union” or “labor” in the title, 11 prominently featured smoking cessation or workplace smoking policies and labor unions. Summarizing these 11, as well as 7 other articles identified by Barbeau60 and an in-depth case study involving multiple constituencies, including unions,62 we found 7 studies that examined early attempts by the tobacco industry to form alliances with unions in the tobacco industry through a labor management coalition with the Tobacco Institute (the trade association of major US tobacco companies).63,64 Women workers (Coalition of Labor Union Women)59,65 and African American and Latino labor organizations61 were among the unions targeted in these collaborative efforts. In these cases, coalition building began in the 1980s with the tobacco industry using issues such as an unpopular cigarette excise tax and workplace smoking restrictions to promote alliances.60 As these studies suggest, that unions were receptive to the tobacco industry alliance can be explained by their reluctance “to intervene on members’ personal health habits, particularly when other workplace health hazards remained uncontrolled” and by the facts that unions represent both smokers and nonsmokers, that the evidence based on secondhand smoke was not yet compelling, and that “tobacco control advocates were not reaching out to labor.”60(p119) Further, as Balbach and Campbell65 point out in the case of the Coalition of Labor Union Women, union opposition to the cigarette excise tax during the decade from 1987 to 1997 may have been further encouraged by the tobacco industry’s provision of direct financial support to the union as well as in-kind support for many of its events.

Finally, in a case study analysis of the genesis and demise of Minnesota’s first in the nation statewide antitobacco campaign (1985–1993), Tsoukalas and Glantz62 note that whereas one strategy of the tobacco industry was to discredit the research on which the intervention was based, another was to reach out to business, labor, and other potential supporters to help defeat the campaign. Further, although the industry had successfully recruited a Teamsters Union spokesperson to lobby in the state capitol and although it continued its outreach to other unions and businesses,

neither the Department of Health nor the tobacco control advocates appear to have worked to hold these constituencies as the tobacco industry lured them.”62(p218)

Even early on, however, the tobacco industry was not “uniformly successful in aligning with labor.”60(p123) This is evident by labor’s support of an airplane smoking ban,66 fire-safe cigarette legislation,64 a New York state tobacco tax,67 and smoking restrictions in New York City bars and restaurants.68 Yet as Brown et al.69 point out, drawing on a Bureau of National Affairs survey,70 although more than a third of employers (36%) had smoking policies in place by the early 1980s “unions remained reluctant to support workplace smoking policies or to promote smoking cessation among their members,” in part because “none of the company smoking policies was developed in consultation with unions representing the company’s employees.”69(p318)

These contradictory trends were further observed in the 1990s. A 1996 survey revealed that 48% of local union leaders supported a total ban or smoking restrictions in the workplace.71 Yet management’s failure to include unions in deciding on antismoking policy development, not infrequently, led to reluctance among unions to support these efforts. Indeed, a review of 90 smoking-related arbitration cases and unfair labor practices filed with the National Labor Relations Board revealed that unions were not protesting the actual smoking policy but “the failure of management to negotiate over these workplace changes.”72

A more recent investigation of public sector unions in New York revealed that many in labor embraced state guidelines or regulations on smoking.73 Labor unions in many parts of the country also increasingly worked with public health and other tobacco control forces on issues such as integrated smoking cessation programs and tailored interventions in the workplace,71,74–79 union-based insurance coverage for such programs,67 and smoke-free workplaces.60

Even today, however, difficult dilemmas sometimes occur when unions do not feel sufficiently engaged in the policy change process or when support for tobacco control bumps up against potentially even greater union and membership concerns for individual privacy and worker rights “off the job,” 2 issues that go back decades.80 This fundamental juxtaposition must be openly addressed and confronted even as many public health and other tobacco control stakeholders increasingly work with labor to promote smoke-free worksites and view labor as a “viable community-based channel for smoking cessation efforts.”60(p126) Earlier lessons about the need to develop workplace smoking policies in close collaboration with union representatives, and for health department and other antitobacco forces to court unions as seriously as big tobacco has, also emerge from this review of unions and tobacco control.

Unions and Hypertension

Although more than a thousand peer-reviewed articles on hypertension included some reference to work or labor unions, the great majority of these referred primarily to the union acting as a source of access to, or recruitment site for, study participants.81–83 This finding is interesting and highlights an oft-overlooked role unions fill as a point of access in medical and public health research and intervention efforts. By contrast, only 36 articles focused more broadly on the role of unions in the prevention and treatment of hypertension. Among these articles numerous themes can be found: the role of unions and labor–management partnerships in the screening, detection, and treatment of hypertension84–87; the union as a key component of community-level and socioenvironmental cardiovascular risk reduction strategies88–91; the union as research or program sponsor85,92; and the union as holding responsibility for addressing risk-related factors.93 Our review also found that nonhealth journals, such as the Journal of Managerial Psychology, publish articles on hypertension, related workplace conditions, and the role of unions.94

It is important to note that in some studies, unions may play an active role, including creating the conditions for health surveillance and research,95 yet not be prominently featured in peer-reviewed journals for political or other reasons. The San Francisco Muni Health and Safety Study, a now classic effort to understand and address hypertension and other adverse health outcomes in urban transit operators, highlights this phenomenon well.95–97 This study, and the more than 26-year union–management–researcher collaboration it spawned, uncovered the collective capacity of these partners for effectively studying hypertension and other health conditions. But it further documented the collaboration’s utility for creating interventions to address underlying causes, such as job stress at the individual, organizational, and environmental levels. Finally, this case unveiled the capacity of the partnership for conducting the work in a manner that was empowering for the worker participants. The groundwork for this project was laid by labor successfully negotiating for new standards and centralizing mandatory health examinations in 1976. The subsequent multiple epidemiological observations, studies, and interventions that took place have been critical to the broader study of hypertension and urban transportation workers globally.96,98–100 Yet very little attention has been paid to the role of the union in this landmark effort. Although the book Unhealthy Work dedicates a chapter to the role of labor in the MUNI Health and Safety Project,95 an examination of the peer-reviewed literature on, or prominently featuring, this case study revealed that just 10 of 26 articles included the terms “Transportation Workers Union,” “TWU,” or “Local 250A,” despite it being a central player in the research. Further, of these 10 articles, only 1 featured “union” in the title.101

Unions and Asthma

With much recent occupational health work and union partnerships in green cleaning and chemical hazards,102–104 conducting a more focused search on asthma prevention efforts at the workplace with unions as key partners was important. Using the search terms “asthma,” “asthmagen,” and “labor union,” we identified 936 articles, of which just 29 were on topic, met all criteria, and were used in the final analysis. Similar to the research on hypertension and smoking cessation, all articles could be grouped into 2 broad categories: (1) those that feature the union as a point of access to, or source of recruitment for, the population of interest (n = 13); and (2) those in which the union was playing an active role in asthma surveillance or intervention (n = 16).

Articles on the prevalence of asthma or asthma-related diseases and exposures featured a wide distribution of worker and workplace types that included construction workers,105–107 garment workers,108 transportation workers,109 plumbers and pipefitters,110 and emergency responders and others working at the World Trade Center site on and after September 11, 2001.111,112 Focusing on the role of unions in asthma interventions, both workplace interventions and community- and policy-level interventions are seen. At the workplace, asthma interventions were included as a component of health promotion113 and workplace environment controls.114 One article listed unions, along with workers, employers, and worker’s compensation regulations, as being among the impediments to asthma-related controls, but did not provide details.114 Many more articles, however, found the union to support the design and implementation of government-sanctioned surveillance programs to reduce problems such as black lung115 and dust diseases in construction116 and cotton fields.117 Additionally, articles highlighted unions as partners with management and researchers through participatory research,118 through public agencies,103,119 or with community and environmental groups to improve asthma-related conditions for workers, consumers, and the broader community.120–123 Included among these campaigns were green industry efforts in Los Angeles,123 clean air campaigns in California,120 and a New York City smoke-free act to reduce secondhand exposures to asthmagens.121

UNIONS AS A PUBLIC HEALTH INSTITUTION

Two case studies illustrate a more expansive and visible role for unions in public health and are exemplars of what would be possible if this often underused partner were more actively engaged across multiple rings of the ecological framework.

Worker as Change Agent in the Hotel Industry

In the 1990s, hotel room cleaners’ workloads began to increase as a result of “lean staffing” and other practices. By the early 2000s they were at intolerable levels.124 Recognizing their members’ lived experience (e.g., making beds with increased pillows, sheets, and duvets and cleaning larger rooms under pressure to work faster) as expert knowledge, the San Francisco–based Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union Local 2 took an unorthodox approach to engage their members as coresearchers. With the often unheard voices of its overwhelmingly female, immigrant, and linguistically and culturally isolated membership at the fore, the union initiated, and helped fund, a participatory study of workplace conditions in 4 major San Francisco hotels. As part of their union–academic partnership agreement, the union agreed to the publication of study results even if those findings did not support the union’s position.125 Local 2’s participatory research partnership with the Labor Occupational Health Program and University of California, Berkeley researchers illustrates how changing the expert paradigm to include workers can increase worker empowerment and create hotel, and industry, change.126

The partnership embodied participatory action research, which Green et al. define as “systematic investigation, with the collaboration of those affected by the issue being studied, for the purpose of education and taking action or effecting change.”127(p4) Participatory action research principles enhanced the unique ability of unions to engage in public health research and create sustained public health change via contractual intervention. The principles included creating a genuine partnership with workers on issues of their choosing, respecting workers’ expert knowledge, and building on their resources and leadership structures to translate research into action. The research implementation plan included identifying the formal structural and leadership assets of the union and accessing the in-depth knowledge of the workers from study design through data interpretation.126 Twenty-five room cleaners participated in the partnership’s research committee, actively engaging in survey design, recruitment strategies, and survey administration. Their role was particularly important in helping achieve a close to 70% response rate (n = 258).126

Findings from joint data analysis of survey responses suggested “an association between poor working conditions and reduced health in hotel room cleaners.”126(p279) This result along with additional findings on job stress, increased workload, and high rates of work-related pain and disability were used in contract negotiations. Making use of the privileged position of University of California researchers to add credibility, the lead academic partner presented the findings at the bargaining table alongside room cleaners. The data justified contract proposals “calling for a significant reduction in housekeeping workload.”126(p280) Local 2 succeeded in negotiating “reduced maximum required room assignments,”126(p280) and they won language on future health studies for additional worker groups in San Francisco’s hotel industry.

The research to bargaining table success also led to new possibilities for the union and hotel employers across the country.125 Indeed, in a subsequent participatory action research study with culinary workers in Las Vegas, a similar process was followed with the largest Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union Local (the Culinary Workers Union Local 226), a core group of workers, and academic partners. In several large hotels along the Las Vegas strip, an even higher response rate was achieved (74%), strong evidence of the adverse effects of working conditions on worker health uncovered, and several additional contractual victories won.128

The San Francisco and Las Vegas studies both illustrate how effective public health–union–worker collaborations contributed to changes on several rings of the ecological model. Hotel workers described personal feelings of improved morale and empowerment, including having their voices heard at hearings and in other venues. Through their interactions with each other and their respective unions, they also experienced stronger social networks at the workplace. Changes resulting from data-driven evidence and powerful testimony at the bargaining table led to improved work environments and working conditions. Although it is difficult to show effects on the outermost ring of the ecological model, should such labor–researcher collaborations continue to spread, they may indeed help change the broader, sociocultural, and environmental conditions that create and maintain the structural patterning within which the power and health of workers and their communities are defined.

Crusade for Safe Schools

Community, workplace, education, and health intersect in the classroom. The health of the school environment affects those who teach and learn in it as well as local families and the community. When children are at school, teachers play a critical role in keeping them healthy and safe. Through their union structures, teachers enforce and create healthy schools at the school, district, and state levels. This is well illustrated by the New Jersey Education Association’s (NJEA’s) collaboration with the New Jersey Work Environment Council (WEC), the oldest blue–green alliance in New Jersey.129

The collaboration of NJEA and WEC expanded opportunities for teachers to have an impact on the school environment. Beginning as a contractual relationship for industrial hygiene technical assistance for local NJEA associations, the NJEA–WEC partnership grew as a combination of factors came together, among them mutual interest in healthy schools coalition building. At the individual level, teachers received WEC materials and training on healthy schools as well as on organizing techniques to bring about needed changes. Teachers were also encouraged to attend union-sponsored health and safety conferences. Local school and district teacher councils received technical assistance from WEC’s industrial hygienists to better identify problems, assist with school walk-throughs, and target solutions. Through member organizing, partnering with parent groups, and financial support from local union chapters, impressive victories occurred. Speaking of NJEA’s efforts, past president Joyce Powell stated,

Over the past seven years, the NJEA built a strong health and safety program that includes education, technical assistance, and policy work. We recognize the enormous benefits of health safety organizing, including better working conditions, better staff and student performance, membership satisfaction, [and] leadership development.129(p128)

At the local association level, activism in health and safety was encouraged. NJEA’s health and safety manual emphasized action in the form of school- or district-based surveying of members, onsite walk-through evaluations, health and safety committees, assisting injured workers, and building coalitions.129 In the 2007 manual, 10 steps to healthy schools were described: commit, organize, research, document, educate, assist, solve, mobilize, negotiate, and use Public Employees Occupational Safety and Health standards. In Passaic, New Jersey, health and safety committees were set up in each school to survey members and address issues with the school administration. Through this process, asbestos was found and removed from district schools. In East Orange, through contract negotiations with the district, a permanent health and safety advisory committee was established with strict timelines for issue resolution. In Patterson, teachers took to the streets to demand a safe school. Upon returning from summer break, teachers immediately noticed that school renovations had not been completed, with trash, asbestos, and hazards materials still in classrooms. After doing a walk-through, the union demanded immediate evacuation of the school and used media coverage to convey a strong message to the district. As a result, students and teachers were relocated to a safe school for the remainder of the construction.129

With local affiliates in every school district in New Jersey, and a growing concern about the health and safety of the school environment, the union looked to the state to make across-the-board changes. In 2004, working with the New Jersey Department of Health and Human Services, a Healthy Schools Ad Hoc Committee was formed. In addition to the union and WEC, other advocates and all 6 state agencies responsible for aspects of healthy schools attended quarterly meetings. Through this committee, the state’s issue awareness increased, new agreements were formed regarding processing school facility complaints at the state level, a Healthy School Facility Environment Web site was launched as a public gateway to an online resource on healthy schools (http://www.state.nj.us/health/healthyschools), and a report on model school districts’ policies was published.129 Outside the committee, NJEA, assisted by WEC, also led legislative efforts on regulating the school environment. These efforts included requiring school closures if temperatures in the school were too high or too low and increasing the enforcement of indoor air quality standards. Although to date the latter have not led to new legislation, the advocacy resulted in new protocols and amendments for school inspection, including an inspection checklist for school construction and reoccupancy and a definition of and rules concerning “sick building syndrome”: health conditions associated with indoor air pollution and other environmental characteristics of workplaces and residencies.129

Although the governor has not signed additional proposed legislation to support green schools in New Jersey,130 the teachers’ union provides a powerful example of the synergy between worker health, community health, and unions. As unions interface with school boards and state agencies, they provide a unique venue through which to advocate healthy schools. In this example, we find a strong case for building interorganizational collaborations that include labor, government, and other sectors, as well as another illustration of the role of social relationships in improving environments. As in the earlier hotel worker case, teachers can be seen directing interventions away from the individual and toward the institutional, community, and policy levels of the ecological model.

CONCLUSIONS

Whether one’s work is situated in a factory or a classroom, a hotel or a field, conditions and policies of the workplace affect the health of workers. These worksites, like the pump handle of yesteryear, need to be examined as sites of public health beyond the traditional boundaries of occupational health. Just as public health departments, foundations, research institutions, and public health agencies increasingly ask for a place-based approach to health, the public health community at large must continue to challenge its own definitions of place to include all environments, including, importantly, the workplace.

Our review of the early history of unions in the United States has demonstrated how well situated this institution has been for addressing inequalities in health by coordinating intervention at all levels of the ecological model. We highlighted how the union’s role often has been critical in facilitating worker empowerment and addressing power inequalities at the heart of community health. Despite the decades-long decline in union membership, we have cited evidence that the successes of unions in improving wages and benefits for their members have in turn positively affected conditions for nonunion workers, contributing to changes on the outermost ring of the social–ecological framework with important outcomes at each other level.

At the same time, and particularly in the case of early tobacco control efforts, our review demonstrates that unions can and do sometimes oppose a proposed public health measure that also involves issues such as privacy, personal behavior change, and regressive taxation. In such cases, whether public health and its allies work early and continuously to engage unions and take their concerns into account or neglect these institutions as they are being actively courted by the opposition, can also be an important factor in determining where unions ultimately stand.62,65,69 Taking a lesson from experience with unions and tobacco control, the importance of forming coalitions from the outset and ensuring that worksite health policies are not imposed from above but codeveloped and implemented must be taken to heart. Public health advocates also are well advised to support other union priorities in which there is a good fit.17,62,65,69

Our targeted reviews of union engagement in public health research, practice, and policy concerning hypertension and asthma were promising, but they each also point to the often-limited role unions have been invited to play (e.g., as a point of access to workers or workplaces). As highlighted in the San Francisco Muni Health and Safety Study, moreover, the actual role of unions, even when central to the research and intervention, may be minimized or rendered invisible, particularly in the peer-reviewed literature for political reasons or fear of having the study appear biased.95

Challenges have also arisen with unions in which public health issues and actors collide. In the case of the early tobacco control movement, the unions’ diverse membership (e.g., smokers and nonsmokers) and hesitance to call for individual behavior change when broader workplace conditions needed to be addressed were among the obstacles we identified. As Barron et al.,10 Kreiger,6 and others113 point out, however, neither approaches that emphasize personal behavior change nor those calling solely for workplace interventions are sufficient, as they fail to “consider the interaction of these and other environmental, economic and social determinants of health.”10(p2) The hierarchical nature of unions has been also cited by some as making it difficult for local unions to partner on public health or other issues not on the agenda of the larger organization. Problems such as the continued underrepresentation of women in the leadership of many local unions, despite improvements in gender equity at the top,49,50 may also limit the interest or effectiveness of some unions in working on certain public health issues. Benefits that primarily affect women workers, such as flextime to accommodate caregiving roles and gender equity in income and career mobility (which sometimes are lost sight of in the broader fight for fair wages for all and health care), have important public health consequences. To be better positioned to partner with public health on such issues, unions need to improve their own commitment to gender equality in leadership—particularly on the local level, where male dominance is especially strong.50 Further, although many unions have evidenced a strong commitment to diversity (e.g., hiring multilingual staff of a wide range of races and ethnicities and supporting the rights of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender workers), labor organizing in immigrant-dominated industries remains underdeveloped.131

Finally, labor unions have had a complicated history in other areas, such as the struggle for environmental health. As Senier et al. note,

Alliances between labor unions and environmental organizations . . . have historically faced formidable obstacles, typically articulated as a class divide that forces union workers to choose between job security and environmental reform.102(p170)

As these and other analysts note, however, these groups have both an old history and more recent successes in building effective blue–green alliances, working together on shared goals of cleaner communities and safer and sustainable jobs.17,102

As the literature also suggested, however, a major obstacle to union participation in public health campaigns is that they simply are not invited to the table. In the most egregious example cited, when big tobacco made a point of inviting unions representing women and people of color to partner in opposing tobacco control efforts, they were taking advantage, in part, of a vacuum left by public health’s failure to engage with unions in the early days of antitobacco organizing.

As the workplace is rendered more visible as part of the place that matters in public health (beyond the confines of occupational health and safety narrowly defined), the primary actors that affect its health—employers, workers, their respective associations, and their collective bargaining bodies—should be more actively sought out as key partners on a wide range of public health issues and initiatives across the social–ecological framework.

This article focused on 1 such organization that is interacting at the individual, interpersonal, workplace, community, and sociopolitical level to intervene on worker health—the union. The 2 case studies highlighted, although chosen in part for their dissimilarity in terms of issues, geography, and populations served, both exemplify the role that unions can play as active and highly engaged partners in public health research, practice, and policy. In each case, the respective unions were doing far more than simply producing healthful ends in contract language and policy changes. They were also producing new and durable structures that moved their work beyond any single health issue through grievance structures, workplace committees, research, and bargaining teams. It is here that unions begin to distinguish themselves from most other public health institutions. Although any employer or legislative body can make a healthy policy for the workplace and public health research institutions can make evidence-based recommendations, the union is making workplace and policy change and, often, simultaneously transforming the psychological and social structures of health.

This is important, as research has shown that decision latitude, demand–reward balance, skill use, job pressure, interpersonal relationships within the workplace, and workplace culture can all “promote or undermine health and well-being.”8(p103) Marmot et al.52 and others8,52,54,132–135 investigating how the work environment affected worker health found psychosocial factors, such as work-related stress and social support networks, played a significant role—both directly and indirectly—in helping shape the social gradient of health.8,52,54,131,132 Unions can address job control, decisional justice, and other work conditions that are associated with coronary heart disease, high blood pressure, musculoskeletal disorders, and stress.133–135

Case study evidence is not alone in showing this healthful capacity of the union. A study in the 1980s of 771 unionized health care workers in New Jersey found empirical evidence for “union activity”133(p225) to be included in job strain models. The study showed a statistically significant negative association between self-reported “union influence and participation”133(p231) and job dissatisfaction, a key indicator of job stress and demand–control imbalance. More recently, in a study of 1614 Los Angeles home care workers, Delp et al. similarly found that union involvement, as an indicator of job control and support, has a direct positive effect on job satisfaction.136 Decisional justice—the ability of workers to have a seat at the decision table and an equal voice in the workplace and the larger sociopolitical arena—is affected as racial/ethnic barriers are replaced by union solidarity, hotel room cleaners and teachers are recognized as experts and researchers, and workers demand changes in the political arena. In these cases, one also sees how “unions, as units of identity and collective action, are ideally suited for engagement in community-based participatory research”137(pS490) and other forms of place-based health research.

As unions win increases in wages and benefits, make improvements to workload, and advocate an improved school system, they are raising their collective voice to challenge the accepted forms of resource distribution, hierarchical power dynamics, and traditional levers of societal health.33,138 Further, as unions traverse the ecological model and work increasingly across levels and fields, they are often affecting the sociopolitical system in a health-promoting way.33,134,138–140 At the same time, the current political environment in which unions are operating may have clear consequences for their current and future ability to help create healthy jobs and healthy communities. The increasing passage of right-to-work legislation at the state level and the recent 5–4 decision of the Supreme Court in the Harris v Quinn case (in which the court decided Illinois home care workers who serve clients of Illinois-administered rehabilitation program are not “full-fledged” public employees)141,142 provide examples of this political climate and also indicate potential areas in which public health partnerships with unions may play an important role.

Limitations

Our work has several limitations. The literature review was not comprehensive or rigorously systematic, and it was restricted to the few union-related research and action campaigns published in the English peer-reviewed literature. Similarly, the small number of case examples we have presented in more detail further limits the database on which our perspectives are based. Despite these limitations, however, we have presented several implications for public health research and practice. First, more rigorous research is needed to truly understand the complex mechanisms that make unions healthful in both their ends and means and that more carefully uncover the pathways from union activity to measureable health outcome. Prospective studies that examine specific union-promoted (or union-opposed) campaigns over time and ideally include collaborative research with academic and other public health partners, further, should be undertaken to strengthen the evidence base in this area. Public health research also should include a systematic review of the literature, including the gray (non–peer-reviewed) literature on unions and health and both the challenges and the facilitating factors involved in this work. Second, the public health community at large should enter into greater dialogue and partnership with organized labor. Increasingly public health practitioners and researchers can look to unions as sites of health innovation, collaboration, and research dissemination.31,33,125,128,134,137

Future Directions

In sum, and despite some continuing challenges, unions can help in defining health-related problems and solutions, reaching out to affected workers, disseminating research findings, and advocating needed changes. As our examples illustrate, however, collaboration may pose problems, and strategies are needed for effectively engaging unions in public health research and practice. First, full involvement, trust, and buy-in can only be achieved if unions are treated as full partners in intervention efforts and brought into the process as early as possible.17 Second, because union structure and hierarchy can either impede or support project involvement, researchers seeking to engage unions must understand how decisions are made and who needs to be involved in the decision-making process. Finally, public health practitioners should be able to articulate how public health initiatives align with union priorities. If public health and union goals appear to be in conflict—as in the case of antismoking campaigns that seemed to infringe on members’ privacy and job security—getting union support and collaboration may be challenging. As the MUNI and hotel housekeeper studies showed, however, fruitful collaboration can take place when public health research is aligned with union goals of building leadership and, when the findings support it, aiding contract campaigns and enhancing services to existing members.

Finally, and in light of promising evidence to date of the health benefits of union membership,33,58 public health practitioners and institutions should do more to protect, and enhance, the unionization of workers across industries. In partnership with unions, the public health community can maximize its success in creating new standards within and across industries, promoting workplace and community health research, uncovering social determinants of health, and decreasing disparities. Falling union membership is public health’s loss; union revival is our opportunity.

Acknowledgments

Early work on aspects of this study was supported in part by the University of California’s Center for Collaborative Research for an Equitable California, and we are deeply grateful for its support.

We gratefully acknowledge our colleagues at the School of Public Health, Labor Occupational Health Program, University of California, Berkeley for their helpful insights on an earlier draft of this article. Special thanks are due Rachel Morello-Frosch, Robin Baker, Seth Holmes, and research librarian Karen Andrews. We are also very grateful to Sherry Baron, Ken McLeroy, and the anonymous reviewers of this article for their helpful suggestions, which greatly improved the article. Finally, our deepest thanks go to the workers and unions who have partnered on efforts to improve the public’s health.

Human Participant Protection

This study was exempt from human participant review because we obtained data from secondary sources.

References

- 1.Samet JM. Epidemiology and policy: the pump handle meets the new millennium. Epidemiol Rev. 2000;22(1):145–154. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. PolicyLink. Why place matters: building a movement for healthy communities. 2007. Available at: http://www.policylink.org/sites/default/files/WHYPLACEMATTERS_FINAL.PDF. Accessed September 3, 2012.

- 3.Brody H, Vinten-Johansen P, Paneth N, Rip MR. John Snow revisited: getting a handle on the Broad Street pump. Pharos Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Med Soc. 1999;62(1):2–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. University of California, Los Angeles, School of Public Health. Removal of the pump handle. Available at: http://www.ph.ucla.edu/epi/snow/removal.html. Accessed October 10, 2013.

- 5.Cassel J. The contribution of the social environment to host resistance: the fourth Wade Hampton Frost lecture. Am J Epidemiol. 1976;104(2):107–123. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krieger N. Epidemiology and the People’s Health: Theory and Context. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization. Ottawa charter for health promotion. Available at: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en. Accessed November 10, 2013.

- 8.Ettner SL, Grzywacz JG. Workers’ perceptions of how jobs affect health: a social ecological perspective. J Occup Health Psychol. 2001;6(2):101–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asfaw A, Pana-Cryan R, Rosa R. Paid sick leave and nonfatal occupational injuries. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):e59–e64. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baron SL, Beard S, Davis LK et al. Promoting integrated approaches to reducing health inequities among low-income workers: applying a social ecological framework. Am J Ind Med. 2013;57(5):539–56. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar S, Quinn S, Kim K, Daniel L, Freimuth V. The impact of workplace policies and other social factors on self-reported influenza-like illness incidence during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):134–140. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linnan LA, Reiter PL, Duffy C, Hales D, Ward DS, Viera AJ. Assessing and promoting physical activity in African American barbershops: results of the FITStop pilot study. Am J Mens Health. 2011;5(1):38–46. doi: 10.1177/1557988309360569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quach T, Liou J, Fu L, Mendiratta A, Tong M, Reynolds P. Developing a proactive research agenda to advance nail salon worker health, safety, and rights. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2012;6(1):75–82. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sorensen G, Landsbergis P, Hammer L et al. Preventing chronic disease in the workplace: a workshop report and recommendations. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(suppl 1):S196–S207. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foner P. History of the Labor Movement in the United States. New York, NY: International Publishers Company, Inc.; 1947. [Google Scholar]

- 16. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Union members in 2008. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/union2_01282009.pdf. Accessed October 13, 2013.

- 17.Baker R, Stock L, Velazquez V. The roles of labor unions. In: Levy BS, Wegman DH, Baron SL, Sokas RK, editors. Occupational and Environmental Health: Recognizing and Preventing Disease and Injury. 6th ed. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 699–713. [Google Scholar]

- 18. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Union members—2013. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/union2.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2014.

- 19.Skurzynski G. Sweat and Blood: A History of U.S. Labor Unions. Minneapolis, MN: Twenty-First Century Books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cogswell D. Unions for Beginners. Hanover, NH: Steerforth Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kennedy JF. Speech of Senator John F. Kennedy, Cadillac Square, Detroit, MI—September 5, 1960. Available at: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=60408. Accessed February 17, 2013.

- 22.Aldrich M. Safety First: Technology, Labor, and Business in the Building of American Work Safety 1870–1939. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green J. Death in the Haymarket: A Story of Chicago, the First Labor Movement, and the Bombing That Divided Gilded Age America. New York, NY: Anchor Books; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwartz R. The Legal Rights of Union Stewards. Cambridge, MA: Work Rights Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riddell WC. Unionization in Canada and the United States: a tale of two countries. In: Card D, Freeman R, editors. Small Differences That Matter: Labor Markets and Income Maintenance in Canada and the United States. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1993. pp. 109–148. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reich R. Aftershock: The Next Economy and America’s Future. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eidelson J. Will “alt-labor” replace unions? Salon.com. 2013. Available at: http://www.salon.com/2013/01/29/will_alt_labor_replace_unions_labor. Accessed November 10, 2013.

- 28.Liu E. Viewpoint: the decline of unions is your problem too. Time. 2013. Available at: http://ideas.time.com/2013/01/29/viewpoint-why-the-decline-of-unions-is-your-problem-too. Accessed November 10, 2013.

- 29.Bernhardt A, Milkman R, Theodore N . Broken Laws, Unprotected Workers: Violations of Employment and Labor Laws in America’s Cities. New York, NY: National Employment Law Project; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leigh JP. Employee and job attributes as predictors of absenteeism in a national sample of workers: the importance of health and dangerous working-conditions. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33(2):127–137. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90173-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown MP. Labor’s critical role in workplace health and safety in California and beyond—as labor shifts priorities, where will health and safety sit? New Solut. 2006;16(3):249–265. doi: 10.2190/3564-11K2-2152-1J22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fletcher JM, Sindelar JL, Yamaguchi S. Cumulative effects of job characteristics on health. Health Econ. 2011;20(5):553–570. doi: 10.1002/hec.1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reynolds MM, Brady D. Bringing you more than the weekend: union membership and self-rated health in the United States. Soc Forces. 2012;90(3):1023–1049. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Stockholm, Sweden: Institute for Futures Studies; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mcleroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stokols D. Establishing and maintaining healthy environments: toward a social ecology of health promotion. Am Psychol. 1992;47(1):6–22. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sallis J, Owen N, Fisher E. Ecological models of health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer B, Viswanath K, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 465–482. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woulfe J, Oliver TR, Zahner SJ, Siemering KQ. Multisector partnerships in population health improvement. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(6):A119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeJoy DM. Theoretical models of health behavior and workplace self-protective behavior. J Safety Res. 1996;27(2):61–72. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minkler M, Wallace SP, McDonald M. The political economy of health: a useful theoretical tool for health education practice. Int Q Community Health Educ. 1994;15(2):111–126. doi: 10.2190/T1Y0-8ARU-RL96-LPDU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whitehead M, Dahlgren G. What can be done about inequalities in health? Lancet. 1991;338(8774):1059–1063. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91911-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baker E, Israel BA, Schurman S. The integrated model: implications for worksite health promotion and occupational health and safety practice. Health Educ Q. 1996;23(2):175–190. doi: 10.1177/109019819602300204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR et al. Community-based participatory research: a capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2094–2102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang C, Salvatore AL, Lee PT, Liu SS, Minkler M. Popular education, participatory research, and community organizing with immigrant restaurant workers in San Francisco’s Chinatown: a case study. In: Minkler M, editor. Community Organizing and Community Building for Health and Welfare. 3rd ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2012. pp. 246–262. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quesada J, Hart LK, Bourgois P. Structural vulnerability and health: Latino migrant laborers in the United States. Med Anthropol. 2011;30(4):339–362. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2011.576725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holmes SM. Structural vulnerability and hierarchies of ethnicity and citizenship on the farm. Med Anthropol. 2011;30(4):425–449. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2011.576728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Geronimus AT. Deep integration: letting the epigenome out of the bottle without losing sight of the structural origins of population health. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(suppl 1):S56–S63. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaminski M, Yakura EK. Women’s union leadership: closing the gender gap. Working USA. 2008;11(4):459–475. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berg P, Piszczek MM. The limits of equality bargaining in the USA. J Ind Relat. 2014;56(2):170–189. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Obama B. Remarks by the president at laborfest in Milwaukee, WI—September 6, 2010. Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2010/09/06/remarks-president-laborfest-milwaukee-wisconsin. Accessed February 25, 2014.

- 52.Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S. Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372(9650):1661–1669. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Braveman P. Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:167–194. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith JP. Healthy bodies and thick wallets: the dual relation between health and economic status. J Econ Perspect. 1999;13(2):144–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krieger N. Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: an ecosocial approach. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):936–944. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cubbin C, Pollack C, Flaherty B et al. Assessing alternative measures of wealth in health research. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(5):939–947. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.194175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pollack CE, Chideya S, Cubbin C, Williams B, Dekker M, Braveman P. Should health studies measure wealth? A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(3):250–264. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mishel L, Walters M. How Unions Help All Workers. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Balbach ED, Herzberg A, Barbeau EM. Political coalitions and working women: how the tobacco industry built a relationship with the Coalition of Labor Union Women. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(suppl 2):27–32. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.046276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barbeau EM, Delaurier G, Kelder G et al. A decade of work on organized labor and tobacco control: reflections on research and coalition building in the United States. J Public Health Policy. 2007;28(1):118–135. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Raebeck A, Campbell R, Balbach E. Unhealthy partnerships: the tobacco industry and African American and Latino labor organizations. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(2):228–233. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsoukalas TH, Glantz SA. Development and destruction of the first state funded anti-smoking campaign in the USA. Tob Control. 2003;12(2):214–220. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bryan-Jones K, Bero LA. Tobacco industry efforts to defeat the Occupational Safety and Health Administration indoor air quality rule. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(4):585–592. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Balbach ED, Barbeau EM, Manteufel V, Pan J. Political coalitions for mutual advantage: the case of the Tobacco Institute’s Labor Management Committee. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(6):985–993. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.052126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Balbach ED, Campbell RB. Union women, the tobacco industry, and excise taxes: a lesson in unintended consequences. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(2 suppl):S121–S125. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pan J, Barbeau EM, Levenstein C, Balbach ED. The airplane smoking ban and role of organized labor: a case study. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(3):398–404. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.040592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barbeau E, Yaus K, Mclellan D et al. Organized labor, public health, and tobacco control policy: a dialogue toward action. New Solut. 2001;11(2):121–139. doi: 10.2190/NLN5-XAAN-FEN5-3A7Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Levenstein C, Delaurier GF, Ahmed S, Balbach ED. Labor and the Tobacco Institute’s labor management committee in New York state: the rise and fall of a political coalition. New Solut. 2005;15(2):135–152. doi: 10.2190/9C0M-07MD-EGX1-MD08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brown ER, McCarthy WJ, Marcus A et al. Workplace smoking policies: attitudes of union members in a high-risk industry. J Occup Med. 1988;30(4):312–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bureau of National Affairs. Where There’s Smoke: Problems and Policies Concerning Smoking in the Workplace. Washington, DC: Bureau of National Affairs; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sorensen G. Organized labor and worksite smoking policies. New Solut. 1996;6(4):57–60. doi: 10.2190/NS6.4.h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sorensen G, Youngstrom R, Maclachlan C et al. Labor positions on worksite tobacco control policies: a review of arbitration cases. J Public Health Policy. 1997;18(4):433–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Siqueira CE, Barbeau E, Youngstrom R, Levenstein C, Sorensen G. Worksite tobacco control policies and labor-management cooperation and conflict in New York State. New Solut. 2003;13(2):153–171. doi: 10.2190/BVBH-0AW9-HKEY-DM98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sorensen G, Stoddard AM, LaMontagne AD et al. A comprehensive worksite cancer prevention intervention: behavior change results from a randomized controlled trial (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13(6):493–502. doi: 10.1023/a:1016385001695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ringen K, Anderson N, McAfee T, Zbikowski SM, Fales D. Smoking cessation in a blue-collar population: results from an evidence-based pilot program. Am J Ind Med. 2002;42(5):367–377. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Osinubi OY, Moline J, Rovner E et al. A pilot study of telephone-based smoking cessation intervention in asbestos workers. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45(5):569–574. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000063618.37065.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barbeau EM, McLellan D, Levenstein C, DeLaurier GF, Kelder G, Sorensen G. Reducing occupation-based disparities related to tobacco: roles for occupational health and organized labor. Am J Ind Med. 2004;46(2):170–179. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sorensen G, Barbeau E, Hunt MK, Emmons K. Reducing social disparities in tobacco use: a social-contextual model for reducing tobacco use among blue-collar workers. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(2):230–239. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Barbeau EM, Li Y, Calderon P et al. Results of a union-based smoking cessation intervention for apprentice iron workers (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17(1):53–61. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-0271-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dworkin TM. It’s my life—leave me alone: off-the-job employee associational privacy rights. Am Bus Law J. 1997;35(1):47–103. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hammond IW, Devereux RB, Alderman MH et al. The prevalence and correlates of echocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy among employed patients with uncomplicated hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;7(3):639–650. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80476-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gerber LM, Shmukler C, Alderman MH. Differences in urinary albumin excretion rate between normotensive and hypertensive, White and non-White subjects. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152(2):373–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hedberg GE, Jacobsson KA, Janlert U, Langendoen S. Risk indicators of ischemic heart disease among male professional drivers in Sweden. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1993;19(5):326–333. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Breslow L. An historical review of multiphasic screening. Prev Med. 1973;2(2):177–196. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(73)90063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alderman MH, Davis TK. Blood pressure control programs on and off the worksite. J Occup Med. 1980;22(3):167–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Glasgow RE, McCaul KD, Fisher KJ. Participation in worksite health promotion: a critique of the literature and recommendations for future practice. Health Educ Q. 1993;20(3):391–408. doi: 10.1177/109019819302000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fisher B, Golaszewski T, Barr D. Measuring worksite resources for employee heart health. Am J Health Promot. 1999;13(6):325–332. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-13.6.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Carlaw RW, Mittlemark MB, Bracht N, Luepker R. Organization for a community cardiovascular health program: experiences from the Minnesota Heart Health Program. Health Educ Q. 1984;11(3):243–252. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Norman S, Greenberg R, Marconi K et al. A process evaluation of a two-year community cardiovascular risk reduction program: what was done and who knew about it? Health Educ Res. 1990;5(1):87–97. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Terris M. The development and prevention of cardiovascular disease risk factors: Socioenvironmental influences. J Public Health Policy. 1996;17(4):426–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Barnett E, Anderson T, Blosnich J, Halverson J, Novak J. Promoting cardiovascular health: from individual goals to social environmental change. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(5 suppl 1):107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schoenbaum EE, Alderman MH. Organization for long-term management of hypertension: the recruitment, training, and responsibilities of a health team. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1976;52(6):699–708. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kales SN, Soteriades ES, Christoudias SG, Christiani DC. Firefighters and on-duty deaths from coronary heart disease: a case control study. Environ Health. 2003;2(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hart KE. Managing stress in occupational settings: a selective review of current research and theory. J Manag Psychol. 1987;2(1):11–17. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Antonio R, Fisher J, Rosskam E. The MUNI health and safety project: a 26-year union-management research collaboration. In: Schnall PL, Dobson M, Rosskam E, editors. Unhealthy Work; Causes, Consequences, Cures. Amityville, NY: Baywood; 2009. pp. 229–247. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ragland DR, Winkleby MA, Schwalbe J et al. Prevalence of hypertension in bus drivers. Int J Epidemiol. 1987;16(2):208–214. doi: 10.1093/ije/16.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Krause N, Ragland DR, Greiner BA, Syme L, Fisher JM. Psychosocial job factors associated with back and neck pain in public transit operators. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1997;23(3):179–186. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Greiner BA, Krause N. Observational stress factors and musculoskeletal disorders in urban transit operators. J Occup Health Psychol. 2006;11(1):38–51. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.11.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ragland DR, Krause N, Greiner BA, Fisher JM. Studies of health outcomes in transit operators: policy implications of the current scientific database. J Occup Health Psychol. 1998;3(2):172–187. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.3.2.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Antonio R. Worker–researcher collaboration with San Francisco bus drivers. New Solut. 2005;15(1):37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wigmore D. A. common goal: union and researcher collaboration celebrate the work of June Fisher, MD. New Solut. 2005;15(1):3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Senier L, Mayer B, Brown P, Morello-Frosch R. Contested Illnesses Research Group. School custodians and green cleaners: labor-environmental coalitions and toxic reduction. In: Brown P, Morello-Frosch R, Zavestoski V, editors. Contested Illnesses: Citizens, Science, and Health Social Movements. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2011. pp. 169–188. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pechter E, Azaroff LS, López I, Goldstein-Gelb M. Reducing hazardous cleaning product use: a collaborative effort. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(suppl 1):45–52. doi: 10.1177/00333549091244S106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Simcox N, Wakai S, Welsh L, Westinghouse C, Morse T. Transitioning from traditional to green cleaners: an analysis of custodian and manager focus groups. New Solut. 2012;22(4):449–471. doi: 10.2190/NS.22.4.e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stern F, Schulte P, Sweeney MH et al. Proportionate mortality among construction laborers. Am J Ind Med. 1995;27(4):485–509. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700270404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Oliver LC, Miracle-McMahill H, Littman AB, Oakes JM, Gaita RR., Jr Respiratory symptoms and lung function in workers in heavy and highway construction: a cross-sectional study. Am J Ind Med. 2001;40(1):73–86. doi: 10.1002/ajim.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Oliver LC, Miracle-McMahill H. Airway disease in highway and tunnel construction workers exposed to silica. Am J Ind Med. 2006;49(12):983–996. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tharr D, Echt A, Burr GA. Case studies exposure to formaldehyde during garment manufacturing. Appl Occup Environ Hyg. 1997;12(7):451–455. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Boult C, Kessler J, Urdangarin C, Boult L, Yedidia P. Identifying workers at risk for high health care expenditures: a short questionnaire. Dis Manag. 2004;7(2):124–135. doi: 10.1089/1093507041253271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cantor KP, Sontag JM, Heid MF. Patterns of mortality among plumbers and pipefitters. Am J Ind Med. 1986;10(1):73–89. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700100109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sellers C. September 11 and the history of hazard. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2003;58(4):449–458. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Skloot G, Goldman M, Fischler D et al. Respiratory symptoms and physiologic assessment of ironworkers at the World Trade Center disaster site. Chest. 2004;125(4):1248–1255. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.4.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Punnett L, Cherniack M, Henning R, Morse T, Faghri P. CPH-NEW Research Team. A conceptual framework for integrating workplace health promotion and occupational ergonomics programs. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(suppl 1):16–25. doi: 10.1177/00333549091244S103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Novey HS. Environmental control of the workplace. Clin Rev Allergy. 1988;6(1):45–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02914981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kerr LE. Black lung. J Public Health Policy. 1980;1(1):50–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Moran JB, Roznowski E. Silica update: national conference to eliminate silicosis construction. Appl Occup Environ Hyg. 1997;12(9):581–583. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Imbus HR. Cotton dust. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1986;47(11):712–716. doi: 10.1080/15298668691390539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Cook WK. Integrating research and action: a systematic review of community-based participatory research to address health disparities in environmental and occupational health in the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(8):668–676. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.067645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Majestic E. Public health’s inconvenient truth: the need to create partnerships with the business sector. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(2):A39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Drury RT, Napolis A. Curbs on clean air: a major environmental threat to the poor and people of color. Race Poverty Environ. 2003;10(2):17–19. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chang C, Leighton J, Mostashari F, McCord C, Frieden TR. The New York City Smoke-Free Air Act: second-hand smoke as a worker health and safety issue. Am J Ind Med. 2004;46(2):188–195. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mann E, Ramsey K, Lott-Holland B, Ray G. An environmental justice strategy for urban transportation. Race Poverty Environ. 2005;12(1):6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Barboza E. Organizing for green industries in Los Angeles. Race Poverty Environ. 2006;13(1):56–58. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Cleeland N. Union to vote on strike in Vegas. Los Angeles Times. 2002. Available at: http://articles.latimes.com/2002/may/16/business/fi-vegas16. Accessed October 20, 2014.

- 125.Lee PT, Krause N, Goetchius C, Agriesti JM, Baker R. Participatory action research with hotel room cleaners: from collaborative study to the bargaining table. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 335–353. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Lee PT, Krause N. The impact of a worker health study on working conditions. J Public Health Policy. 2002;23(3):268–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Green L, George M, Daniel M . Study of Participatory Research in Health Promotion: Review and Recommendations for the Development of Participatory Research in Health Promotion in Canada. Ottawa, ON: The Royal Society of Canada; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Krause N, Scherzer T, Rugulies R. Physical workload, work intensification, and prevalence of pain in low wage workers: results from a participatory research project with hotel room cleaners in Las Vegas. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48(5):326–337. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Senn E. New Jersey’s union-centered healthy schools work. New Solut. 2010;20(1):127–137. doi: 10.2190/NS.20.1.i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Gov Senn E. Chris Christie halted critical projects to improve school safety. 2011. Available at: http://blog.nj.com/njv_guest_blog/2011/11/gov_chris_christie_halted_crit.html. Accessed October 20, 2014.

- 131.Leymon AS. Unions and social inclusiveness: a comparison of changes in union member attitudes. Labor Stud J. 2011;36(3):388–407. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Marmot MG, Smith GD, Stansfeld S et al. Health inequalities among British civil-servants: the Whitehall II study. Lancet. 1991;337(8754):1387–1393. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93068-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Landsbergis P. Occupational stress among health-care workers: a test of the job demands-control model. J Organ Behav. 1988;9(3):217–239. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Landsbergis PA, Cahill J. Labor union programs to reduce or prevent occupational stress in the United States. Int J Health Serv. 1994;24(1):105–129. doi: 10.2190/501D-4E1P-260K-2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Rugulies R, Braff J, Frank J et al. The psychosocial work environment and musculoskeletal disorders: design of a comprehensive interviewer-administered questionnaire. Am J Ind Med. 2004;45(5):428–439. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Delp L, Wallace SP, Geiger-Brown J, Muntaner C. Job stress and job satisfaction: home care workers in a consumer-directed model of care. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(4):922–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]