In 2013, the Institute of Medicine reported persistent gaps between the United States and other high-income countries across multiple risk factors, diseases, and health outcomes.1 Large gaps also exist within the United States, and life expectancy appears to be declining in some US counties and population groups.2 These alarming trends cannot be explained by the availability of health care alone; rather, they reflect a complex interplay between the physical and social environment, individual health behaviors, and the health care delivery system.1,2 Achieving progress will require population-based interventions that address these factors that contribute to health.3

THE NATIONAL PREVENTION COUNCIL AND NATIONAL PREVENTION STRATEGY

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is making great strides in increasing health insurance coverage and transforming the health care delivery system to ensure high quality care. Importantly, the ACA also created a platform for population health improvement through the National Prevention, Health Promotion, and Public Health Council (National Prevention Council), which provides leadership and coordination related to health and prevention at the federal level. The Council is chaired by the Surgeon General and includes the heads of 20 federal departments and agencies (see the box on the next page for a full list of members). Bringing together leaders from a diverse set of federal agencies including the Departments of Agriculture, Defense, Education, Housing and Urban Development, and Transportation, the Council’s membership emphasizes that health is not solely the domain of the Department of Health and Human Services; rather, many sectors have a role to play in supporting healthy individuals and communities.

National Prevention Council Members

| Department of Health and Human Services |

| Department of Agriculture |

| Department of Education |

| Federal Trade Commission |

| Department of Transportation |

| Department of Labor |

| Department of Homeland Security |

| Environmental Protection Agency |

| Office of National Drug Control Policy |

| Domestic Policy Council |

| Bureau of Indian Affairs |

| Corporation for National and Community Service |

| Department of Defense |

| Department of Housing and Urban Development |

| Department of Justice |

| Department of Veterans Affairs |

| Office of Management and Budget |

| Department of the Interior |

| General Services Administration |

| Office of Personnel Management |

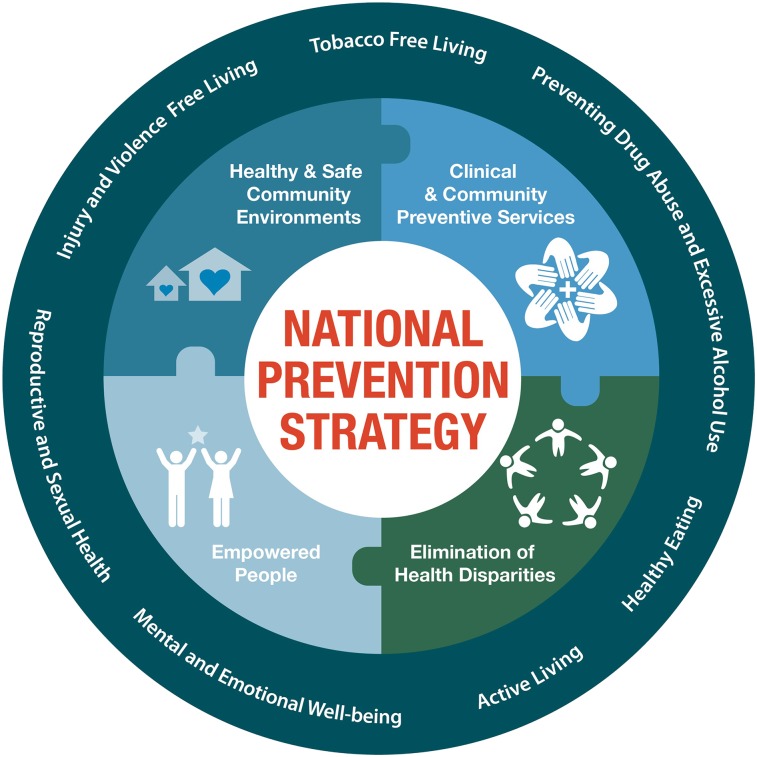

In 2011, the National Prevention Council released the National Prevention Strategy,4 which provides evidence-based recommendations and key indicators across 4 Strategic Directions and 7 targeted Priorities (Figure 1). The National Prevention Strategy explicitly recognizes that many of the strongest predictors of health and well-being fall outside of the health care setting and that social, economic, and environmental factors all influence health. Therefore, its recommendations address a diverse range of partners including businesses and employers, educational institutions, and community organizations as well as local governments and health systems. Its recommendations also reflect the importance of empowering people with information to make healthy choices while working to create environments where healthy choices are easier and affordable.

FIGURE 1—

National Prevention Strategy Framework

FEDERAL PROGRESS IMPLEMENTING THE NATIONAL PREVENTION STRATEGY

Three years into the implementation of the National Prevention Strategy, the Council’s 2014 status report demonstrates important progress in three areas: federal leadership, incorporation of health into cross-sector federal programs, and community implementation.5 The Council has provided a platform for making the federal government a leader in prevention, with a particular focus on reducing tobacco use and increasing access to affordable, healthy food. Since 2011, the Federal Employees Health Benefit Program has included one of the most comprehensive tobacco cessation benefits available, covering counseling for at least two quit attempts per year and approved tobacco cessation medications with no copayments. The Council is working to increase awareness and utilization of this benefit to further reduce tobacco use rates among the federal workforce. At the same time, federal agencies are addressing their own tobacco-free policies. For example, 92% of Naval medical centers, hospitals, and health clinics have tobacco-free policies in place, illustrating major leadership by the Department of Defense, which joins several national hospital systems, clinics, insurers, and health service companies that have adopted smoke-free grounds policies nationwide. The Council has also made major progress in increasing access to healthy, affordable food. In 2013, the National Park Service implemented new Healthy Food Standards and Sustainable Food Guidelines that improve the food offerings for its more than 23.5 million customers each year, and 97% of General Service Administration–sponsored child care centers have attained Let’s Move! certification for incorporating good nutrition and physical activity. These achievements illustrate the powerful example the federal government can set as an employer, purchaser, and service provider.

To achieve the National Prevention Strategy’s vision, federal departments will need to do more than address internal policies. Therefore, Council departments are working to incorporate health into cross-sector federal programs. One of the most powerful examples comes from the Partnership for Sustainable Communities, a major initiative to promote affordable, livable communities through streamlined investment strategies (e.g., coordinated funding and review) across the Department of Housing and Urban Development, Department of Transportation, and the Environmental Protection Agency. Since 2009, the Partnership has provided more than $4.5 billion in funding for more than 1000 projects in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. These investments maximized the positive health effects of neighborhood infrastructure by making walkable neighborhoods a program goal and by measuring progress based on health-related indicators including: active transportation (percentage of workers commuting via walking, biking, transit, or rideshare), lack of access to healthy food choices (percentage of total population that resides in a low-income census tract and resides more than one mile from a supermarket or large grocery store [10 miles for rural census tracts]), and access to open space (percentage of population that resides within one mile of a park or open space for rural areas or within a half mile for cities). This approach illustrates the opportunity to support cross-sector primary prevention by leveraging the diverse programs and policies across the 20 federal departments and agencies that make up the Council.

PARTNERSHIPS FOR POPULATION HEATH IMPROVEMENT

The National Prevention Strategy emphasizes that every sector has a role to play in improving population health, and the Council’s 2014 Status Report also highlights organizations that are bridging the links between health service delivery, social services, and population health. For example, the Philadelphia Corporation for Aging is using the National Prevention Strategy to help older adults remain independent, healthy, and productive in the community, and the National Association of State Workforce Agencies is providing jobseekers with tools and information to address health needs and make healthy choices.

The ACA created a variety of new avenues to promote improved health, lower health care costs, and improved health care quality. As multiple stakeholders from public health, healthcare delivery, and other sectors work to identify their roles as partners in population health improvement, the National Prevention Strategy provides an important roadmap for evidence-based investments in population health, and the Council demonstrates that collaborative federal action can model a successful approach for engaging multiple sectors to begin to address the underlying causes of poor health.

References

- 1.Woolf SH, Aron LY. The US health disadvantage relative to other high-income countries: findings from a National Research Council/Institute of Medicine Report. JAMA. 2013;309:771–772. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kindig DA, Cheng ER. Even as mortality fell in most US counties, female mortality nonetheless rose in 42.8 percent of counties from 1992 to 2006. Health Aff. 2013;32:451–458. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the Health Impact Pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:590–595. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Prevention Council. National Prevention Strategy. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Resources, Office of the Surgeon General; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Prevention Council. 2014 National Prevention Council Annual Status Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Resources, Office of the Surgeon General; 2014. [Google Scholar]