Abstract

Objectives. We aimed to determine the frequency, characteristics, and precipitating circumstances of eviction- and foreclosure-related suicides during the US housing crisis, which resulted in historically high foreclosures and increased evictions beginning in 2006.

Methods. We examined all eviction- and foreclosure-related suicides in the years 2005 to 2010 in 16 states in the National Violent Death Reporting System, a surveillance system for all violent deaths within participating states that abstracts information across multiple investigative sources (e.g., law enforcement, coroners, medical examiners).

Results. We identified 929 eviction- or foreclosure-related suicides. Eviction- and foreclosure-related suicides doubled from 2005 to 2010 (n = 88 in 2005; n = 176 in 2010), mostly because of foreclosure-related suicides, which increased 253% from 2005 (n = 30) to 2010 (n = 106). Most suicides occurred before the actual housing loss (79%), and 37% of decedents experienced acute eviction or foreclosure crises within 2 weeks of the suicide.

Conclusions. Housing loss is a significant crisis that can precipitate suicide. Prevention strategies include support for those projected to lose homes, intervention before move-out date, training financial professionals to recognize warning signs, and strengthening population-wide suicide prevention measures during economic crises.

In 2010, 36 364 persons in the United States died by suicide (age-adjusted rate = 12.08 per 100 000 population), making it the second leading cause of death for US adults aged 25 to 34 years, and fourth for adults aged 35 to 54 years.1 Furthermore, the overall suicide rate in the United States has increased over the past decade,2 especially among adults aged 35 to 64 years.3 Suicide carries enormous costs to society, such as emotional trauma for friends and family members (including heightened risk of subsequently attempting suicide themselves), and medical and work loss costs estimated at $34.6 billion a year.

Persons who engage in suicidal behavioral typically have multiple risk factors for suicide such as depression, substance abuse, or chronic or acute life stressors such as financial problems. In some instances, a precipitating event prompts an attempt in an already vulnerable person. Several studies of US and international economic cycles have found that suicides increase in step with adverse economic events.4,5 For example, a recent study examining the impact of austerity measures taken in England during the European financial crisis on unemployment and subsequent suicides attributed more than 1000 excess suicides to these economic conditions between 2008 and 2010.6 Another found that in Greece, one of the worst-hit economies in Europe, suicide mortality rates among men have increased by more than 22% since 2007.7 Similar trends were observed in several countries (e.g., Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea) following the Asian monetary crisis of 1997.8

An analysis of US business cycles and suicide rates between 1928 and 2007 recently demonstrated that suicide rates in the United States have also generally increased and decreased along with economic conditions.4 The findings demonstrated that US suicide rates peaked during the Great Depression, and decreased during times of economic expansion and low unemployment. Working-age adults were most affected. One recent study attributed up to 25% of the US suicide rate increase seen over the past decade specifically to rising unemployment.9

There were other important dimensions of the recent US economic downturn that may be associated with the observed increase in suicides. Beginning in late 2006, the US experienced a housing crisis characterized by historically high rates of home foreclosure10 and increased evictions.11 Media reports of suicides associated with eviction or foreclosure appeared in national news outlets during this time,12–14 although little information exists about the frequency or characteristics of these events. Although the full impact of the housing crisis on public health is not yet known, several studies have documented adverse effects associated with mortgage delinquency such as 2 or more times greater odds of major depression15,16 and 8 times greater odds of elevated depressive symptoms related to acute stress.17 In addition, a recent study found higher suicide rates in regions experiencing higher rates of foreclosure.18 These findings suggest that eviction or foreclosure may be related to elevated risk of suicide. However, to date, no study has described or directly investigated suicides associated with home eviction and foreclosure.

We determined the frequency and circumstances of suicide deaths linked to eviction (i.e., renters evicted for financial reasons) and foreclosure (i.e., homeowners losing homes to foreclosure) in the years 2005 through 2010 with data from 16 states participating in the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS). Within this sample, we also examined the extent to which eviction or foreclosure was perceived as a key stressor contributing to the decedent’s suicide versus acting in concert with other stressors. Furthermore, we calculated the frequency of eviction or foreclosure suicides relative to other suicides during this time period, and the percentage of all suicides associated with financial stressors that were eviction or foreclosure related.

METHODS

The NVDRS is a state-based active surveillance system of all violent deaths in participating states, including suicides and homicides. Data from the NVDRS have been used to examine the incidence and characteristics of many different types of violence, including intimate partner violence,19–21 child maltreatment,22 gang violence,23 suicide,24 and homicide–suicides.25

The NVDRS links data from multiple sources (e.g., death certificates, coroner and medical examiner reports, law enforcement reports) into a single incident record. State staff review the investigative findings of coroners, medical examiners, and law enforcement as well as death certificate information and abstract information into NVDRS by using standard national coding guidance developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. For instance, NVDRS collects information on the demographic characteristics of the victim, location of the incident, weapon used to inflict the fatal injury, mental health of the victim, and a standard set of circumstances that may be identified in investigative reports as associated with the death. The NVDRS circumstances can also be thought of as “contributing circumstances,” “contributing factors,” or “risk factors” because of the way they are determined by investigators.

Investigators (e.g., law enforcement) typically interview persons who know the decedent to determine circumstances in the decedent’s life that may have contributed to his or her death, and may also be able to infer further information about factors contributing to the death from evidence at the scene of the incident. For example, although financial records would not be routinely reviewed as part of a suicide investigation, investigators could determine in several different ways that eviction or foreclosure contributed to a person’s death by suicide. Friends, family, coworkers, or other persons interviewed could report that the decedent had been experiencing eviction or foreclosure. In addition, evidence may be provided directly by the decedent, such as a suicide note indicating distress over eviction or foreclosure; a phone call to mortgage professionals, police, or other persons; or some other direct reporting of motives. Furthermore, decedents may indirectly indicate eviction or foreclosure as a factor contributing to suicide by leaving a symbol of its importance somewhere that it can be easily found (e.g., an eviction notice taped to the door). Finally, investigators may infer these motives themselves if they find something such as a foreclosure hearing scheduled for the day of the suicide, are there to evict the person when the suicide occurs, or other circumstances where it can reasonably concluded that eviction or foreclosure was a contributing factor.

Abstractors for the NVDRS code the presence or absence of more than 20 standard circumstances (each defined by the NVDRS coding manual) for suicide deaths. These circumstances include mental health problems and treatment (e.g., current depressed mood, current mental health problem, current treatment of mental illness, type of mental health diagnoses, ever treated for a mental health problem, history of suicide attempts, disclosure of intent to commit suicide), substance use and abuse (e.g., alcohol dependence, suspected intoxication at the time of death, other substance problem), problems involving other people or relationships (e.g., intimate partner problem, recent suicide of friend or family member, death of friend or family member, other relationship problem), criminal or legal problems (recent criminal legal problem, other legal problem, victim of interpersonal violence, perpetrator of interpersonal violence), and other chronic and acute life stressors (e.g., physical health problem, job problem, school problem, financial problem).

“Financial problem” is a routinely reported NVDRS suicide circumstance that includes eviction and foreclosure, but also includes problems such as overwhelming debts (e.g., large hospital bills, gambling debts), bankruptcy, or other general financial problems determined by investigators to be contributing factors. This variable is too broad to be used in defining cases for this study, but was used to examine the frequency of eviction- or foreclosure-related suicides relative to other suicides involving more general financial problems by analyzing the frequency of eviction or foreclosure cases as a percentage of overall financial-related suicides. This was important because of the context of other economic problems occurring in same general timeframe, such as the economic recession, rising health care costs, and problems with unemployment.

The NVDRS includes 2 incident narratives that are generated by the state abstractor on the basis of the coroner or medical examiner and law enforcement reports. The narratives contain a chronology of events in the fatal injury incident and a description of circumstances that investigators included in their reports of the person’s death.26

Presently, 18 states (Alaska, Colorado, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin) contribute data to NVDRS. We used data from 16 NVDRS states in this analysis because 2 states (Ohio and Michigan) did not collect data before 2010.

Case Selection

We selected cases by using the following criteria: the decedent died by self-inflicted means, had NVDRS circumstance information (88.9% of all suicide decedents), had experienced a loss of housing or impending loss of housing within the 12 months immediately preceding death, was a rent-paying tenant or owner of the dwelling (e.g., a young person asked to move out of the family home would not be included), the loss of housing could not be determined as related solely to behavioral (e.g., disorderly conduct) or relationship (e.g., divorce) reasons, and the eviction or foreclosure was cited in the law enforcement, coroner, or medical examiner investigative reports of the suicide. Situations in which the decedent had expressed concern about potential eviction or foreclosure, but it was clear that no actions toward either had yet occurred, did not meet the case definition.

We identified potential cases from 2005 to 2009 by conducting word searches of key phrases such as “evicted,” “sheriff sale or warrant of removal,” “foreclosure,” “lost house or home,” in the law enforcement and coroner or medical examiner narratives with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We found cases from 2010 by using a newly created NVDRS variable for eviction or home loss that was completed by state abstractors as part of routine data abstraction. Ninety-three percent of cases captured by the eviction or home loss variable in 2010 were captured by the text search, validating the approach used for the other years.

At least 1 of the authors then reviewed potential cases to determine inclusion. In addition to the variables that are included in NVDRS, the authors coded a few additional variables related to the eviction or foreclosure: type of housing loss (eviction vs foreclosure), timing of suicide in relation to the housing loss (whether suicide occurred before vs after the decedent was required to vacate the dwelling), and whether there was evidence of an acute precipitating eviction- or foreclosure-related event (e.g., suicide occurred day before the eviction was to occur). Rater pairs independently coded 200 potential cases until sufficient interrater reliability was established (range: κ = 0.60–0.93).

Statistical Analysis

We used the χ2 goodness-of-fit test to test the significance of year-to-year changes in the frequency of suicides with eviction or foreclosure circumstances. We used the χ2 test of independence to test the significance of year-to-year changes in the frequency of suicides associated with eviction or foreclosure relative to other suicides.

We conducted analyses with SPSS Predictive Analysis Software version 18 (IBM, Somers, NY).

RESULTS

We identified a total of 929 suicides between 2005 and 2010 with eviction or foreclosure circumstances—51% (n = 473) eviction-related, and 49% (n = 454) foreclosure-related. (It was not possible to determine whether 2 cases were related to eviction versus foreclosure. Therefore, these cases are included in overall analyses, but not in analyses broken into subgroups reflecting type of housing loss.) The majority of the decedents were White (87%) and male (79%; Table 1). The median age of the decedents was 47 years for evictions and 49 years for foreclosures.

TABLE 1—

Demographics of Suicide Decedents With Eviction and Foreclosure Circumstances: National Violent Death Reporting System, United States, 2005–2010

| Variable | Eviction, No. (%) | Foreclosure, No. (%) | Total, No. |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 367 (78) | 368 (81) | 735 |

| Female | 106 (22) | 86 (19) | 192 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 395 (84) | 410 (90) | 805 |

| Black | 44 (9) | 22 (5) | 66 |

| Hispanic | 21 (4) | 13 (3) | 34 |

| Native American | 9 (2) | 5 (1) | 12 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4 (1) | 5 (1) | 9 |

| Age, y | |||

| ≤ 24 | 31 (7) | 5 (1) | 36 |

| 25–34 | 58 (12) | 45 (10) | 103 |

| 35–44 | 98 (21) | 98 (22) | 196 |

| 45–54 | 164 (35) | 180 (40) | 344 |

| 55–64 | 106 (22) | 101 (22) | 207 |

| ≥ 65 | 16 (3) | 25 (6) | 41 |

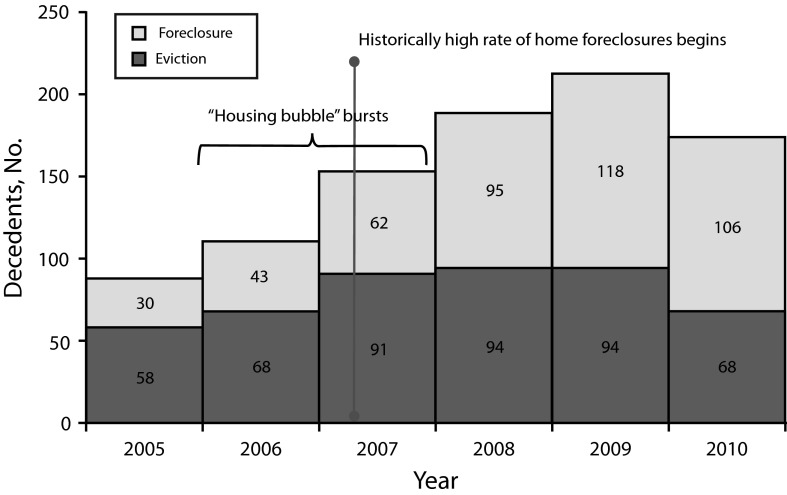

Suicides with eviction or foreclosure circumstances doubled from 2005 to 2010 (n = 88 in 2005; n = 176 in 2010; Figure 1). There was a significant increase in eviction or foreclosure suicides from 2006 to 2007 (χ2 = 6.68; P = .01), and from 2007 to 2008 (χ2 = 3.79; P = .05). Much of this increase was attributable to foreclosure-related suicides, which increased 253% from 2005 to 2010. Increases in foreclosure-related suicides began in late 2007, paralleling the timing of the housing crisis, and peaked in 2009.

FIGURE 1—

Frequency of suicides associated with eviction or foreclosure in context of the US housing crisis: National Violent Death Reporting System, United States, 2005–2010.

Note. The sample size was n = 929. There was a significant increase in eviction- or foreclosure-related suicides from 2006 to 2007 (χ2 = 6.68; P = .01), and from 2007 to 2008 (χ2 = 3.79; P = .05).

Source. Information about timing of the US housing crisis comes from The Economist.10

Comparison With Other Suicides During Same Time Period

Eviction- or foreclosure-related suicides increased significantly more than other suicides captured by NVDRS occurring in the same years (n = 55 193; median = 9181; range = 8486–10 002) when we compared 2006 with 2007 (χ2 = 5.08; P = .02), and decreased while other suicides increased when we compared 2009 with 2010 (χ2 = 15.37; P < .001). Eviction- or foreclosure-related suicides accounted for 1% to 2% of all suicides captured in the system, with a peak in 2009.

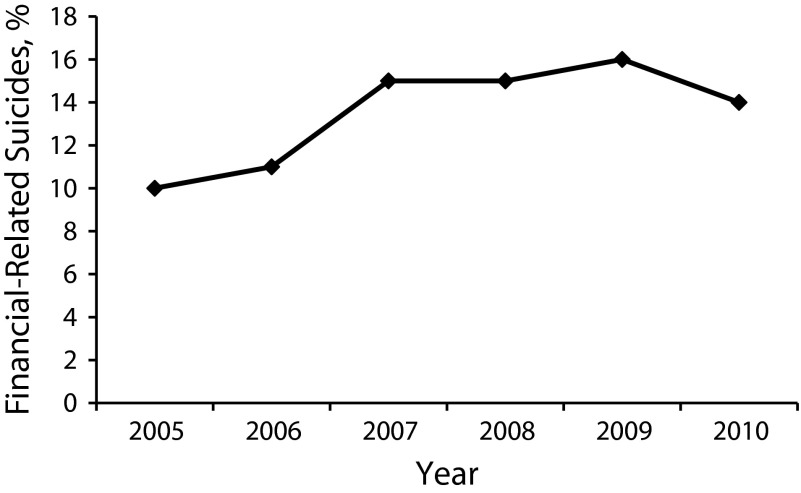

Eviction- or foreclosure-related suicides accounted for 10% (2005) to 16% (2009) of all financial-related suicides (n = 6532; median = 1079; range = 901–1260) captured by NVDRS in each year from 2005 to 2010 (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2—

Percentage of all financial-related suicides that involved eviction or foreclosure problems: National Violent Death Reporting System, United States, 2005–2010.

Note. A total of 6532 suicides with financial circumstances were captured by the National Violent Death Reporting System from 2005 to 2010 (median = 1079; range = 901–1260).

Circumstances Related to Foreclosure or Eviction

Most suicides occurred before the actual loss of housing (79%). Also, 37% of cases experienced a crisis related to the eviction or foreclosure (e.g., a court hearing, an eviction notice, the date on which the person was to vacate the dwelling) within 2 weeks of the suicide.

Overall, the most common NVDRS-coded circumstances associated with the decedent’s suicide other than eviction or foreclosure were current depressed mood (53%), crisis within past 2 weeks (this variable is routinely coded within NVDRS and accounts for a crisis of any type, not just eviction- or foreclosure-related crises; 47%), leaving a suicide note (40%), job problems (38%), and alcohol use suspected at the time of suicide (32%). Thirty-four percent had disclosed suicidal intent to another person.

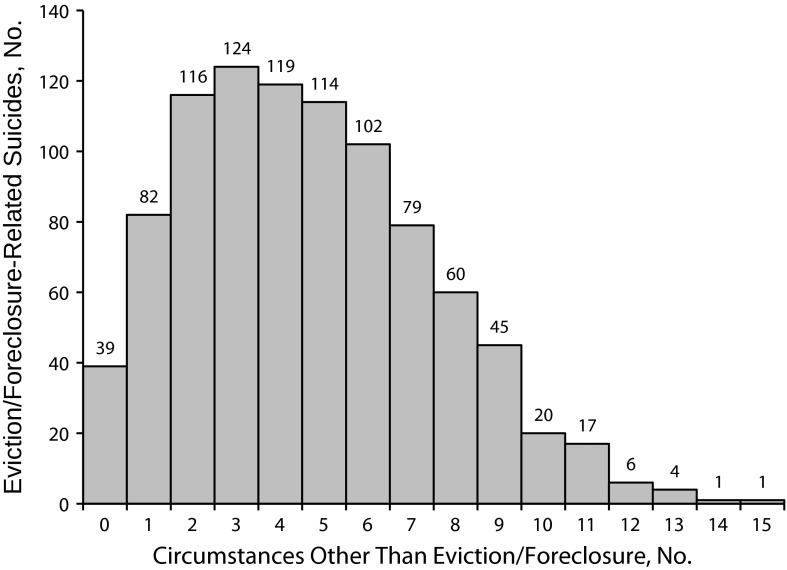

Most decedents had 4 or fewer circumstances other than eviction or foreclosure indicated as contributing factors to their suicide (range = 0–15; median = 4; Figure 3). This is similar to the overall number of circumstances for all NVDRS-captured suicides with any known circumstances during the same time period (n = 51 789; range = 1–15; median = 4), and to the number of additional circumstances for suicides with general financial circumstances (range = 0–15; median = 4).

FIGURE 3—

Number of circumstances other than eviction or foreclosure contributing to suicide for all eviction- or foreclosure-related suicides: National Violent Death Reporting System, United States, 2005–2010.

DISCUSSION

This study was the first to our knowledge to systematically examine suicides linked with eviction and foreclosure. A review of suicide deaths in 16 states found more than 900 eviction- or foreclosure-related suicides between 2005 and 2010. The statistically significant increases seen when we compared 2006 with 2007, and 2007 with 2008 mirror the timing of the onset and deepening of the housing crisis. Importantly, these increases were seen even relative to the frequency of all other suicides in the same states during the same time period, and relative to suicides associated with general financial problems in the same sample. This suggests that the rise seen in eviction- or foreclosure-related suicides was not just part of a general rise in suicides. Although most suicides related to financial problems were not associated with eviction or foreclosure, the percentage that were eviction- or foreclosure-related increased in step with the general increase in frequency of home foreclosure and eviction, again in parallel with the timing of the housing crisis. The largest increase was seen in foreclosure-related suicides, which more than tripled from 2005 to 2010. This further suggests a relationship between these suicides and the housing crisis, which resulted in a national 389% increase in foreclosures between 2005 and 2010.27

Persons who engage in suicidal behavioral typically have multiple risk factors for suicide. A precipitating event then prompts an attempt in an already vulnerable person. This study illustrates the potential significance of housing loss as a crisis that can precipitate suicide attempts.

Our findings suggest that, for some individuals who died by suicide during the US housing crisis, eviction or foreclosure was a very central risk factor. Although most decedents in our sample had multiple circumstances that contributed to suicide, more than 1 in 8 had eviction or foreclosure as the only circumstance or only 1 other contributing circumstance.

Furthermore, the other contributing circumstances most frequently identified were ones that could be viewed as risk factors that combine with eviction or foreclosure to create a mix of acute stress. For example, rather than chronic mental health problems, or a history of substance abuse problems or suicide attempts (circumstances that are also identified when present by NVDRS), the decedents in this sample most frequently were seen as having current depressed mood, likely having consumed alcohol at the time of death, having current job problems (which could be contributing to housing problems), and having told someone that they were thinking about suicide. These factors portray home loss as a result of eviction and foreclosure and related stressors that are likely offshoots of this central problem, as a potentially lethal cascade of stressors.

Foreclosure may be exceptionally stressful because of its protracted nature and multiple negative events that constitute the process,28 particularly given the evidence that situational depression may respond in a dose–response fashion to negative life events.29 In addition, depression is more strongly related to stressful life events for which individuals perceive personal responsibility29 and lack of control over outcomes.30,31 All of these factors are mechanisms that make the foreclosure process a potent psychological stressor.

Others have also noted that foreclosures affect not only individuals but also neighborhoods in ways that contribute to stress, including increases in violent crime,32 and undermining protective factors such as social support by increasing resident transience. More research is needed to understand how foreclosure interacts with neighborhoods to produce a climate more or less conducive to elevating suicide risk.

Limitations

The study is limited by reliance on identification of eviction and foreclosure circumstances by law enforcement or coroner medical examiner records, the data sources for NVDRS. Therefore, it is likely that some eviction- or foreclosure-related suicides went undetected because of these features of the data source. It is also possible the number of cases is an underestimate, because of the conservative case selection approach (e.g., excluding individuals with evidence only of concerns about housing loss) and the small percentage of cases that may have been missed by the text search. On the other hand, it is also possible that increased attention by investigators and NVDRS coders accounted for some portion of the increase, or eviction or foreclosure was misidentified by investigators or witnesses. However, the timing of the increase paralleled the timing of the housing crisis rather than occurring later as the extent of the housing crisis became widely reported in the media.

Also, we did not test the relative contributions of different types of financial distress against one another. This should be done in future studies, which could test eviction or foreclosure against other economic stressors associated with the US recession and combinations of economic stressors, such as unemployment and bankruptcy, as risk factors for suicide. The NVDRS narrative data on suicides with financial circumstances could be reviewed to categorize the nature of different financial stressors represented and to conduct these comparisons. In addition, cluster analyses could further examine whether particular types of financial stressors and other (i.e., nonfinancial) contributing circumstances aggregate in patterns that indicate subtypes of risk for suicide related to financial problems. This type of analysis has the potential to yield more tailored suicide prevention strategies for subgroups of persons at risk.

As a final limitation, this study captures only a portion of all eviction- and foreclosure-related suicides by using a sample of 16 states participating in the NVDRS (e.g., in 2010 approximately 27% of all US suicides occurred in these 16 states). Although this is the first attempt to characterize the scope of these events, the burden is still underrecognized by these findings and is much higher when one considers the entire United States. Also, the number is underestimated because not all suicides had circumstance information available and the role of eviction or foreclosure was most likely not ascertained in all investigations.

Conclusions

In light of the evidence that economic recessions have historically been associated with increases in suicide in the United States,4 some have recommended that policymakers and public health workers increase population-level suicide prevention measures during times of adverse economic conditions.4 These measures are important given different yet related financial stressors (e.g., job loss, personal debt, foreclosure) that may coalesce and increase the risk of suicide. Suggested strategies include providing counseling and social support (e.g., call centers) for those who lose jobs or homes, and promoting connectedness among individuals, families, and their communities.4

These findings have strong implications for public health interventions, such as referral to support services when a person is projected to experience a home loss, intervention before the actual move-out date, and recognition that loss of housing as a result of eviction or foreclosure can be experienced as a significant crisis. The National Strategy for Suicide Prevention33 recommends training a range of professionals, including financial professionals, to recognize suicidal thoughts and behaviors. This is especially important when one considers the high percentage (nearly 80%) of eviction- or foreclosure-related suicides in this sample that occurred before the actual loss of housing. Financial professionals and others who interact with individuals who are in the process of losing their homes may therefore be important gatekeepers in preventing suicide.

A recent study of a small sample of mortgage counselors recruited through the National Foreclosure Mitigation Counseling Program (n = 395) provides preliminary evidence of this importance.34 Sixty-eight percent of these counselors reported that “many” to “almost all” clients seen in the past month appeared depressed or hopeless, and 37% reported working with at least 1 client in the past month who expressed suicidal thoughts. Although 68% of those surveyed perceived it as one of their job responsibilities to refer clients to local health services, only 14% reported receiving any training on this task from their employers. This provides further preliminary evidence that it may be possible to engage financial professionals who counsel clients experiencing housing loss in the process of recognizing mental health problems and providing appropriate referrals, and to bridge this training gap.

Improved awareness and detection of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, and improved knowledge of appropriate actions to take when one is interacting with suicidal individuals, are important steps to the prevention of all suicides, including those related to eviction and foreclosure.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was not required for this project because the data were derived from routine injury mortality surveillance.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). 2005. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/leading_causes_death.html. Accessed November 30, 2012.

- 2.Rockett IR, Regier MD, Kapusta ND et al. Leading causes of unintentional and intentional injury mortality: United States, 2000–2009. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(11):e84–e92. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide among adults aged 35–64 years—United States, 1999–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(17):321–325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo F, Florence CS, Quispe-Agnoli M, Ouyang L, Crosby AE. Impact of business cycles on US suicide rates, 1928–2007. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):1139–1146. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tapia Granados JA, Diez Roux AV. Life and death during the Great Depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(41):17290–17295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904491106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barr B, Taylor-Robinson D, Scott-Samuel A, McKee M, Stuckler D. Suicides associated with the 2008–2010 recession in England: time trend analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e5142. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kondilis E, Giannakopoulos S, Gavana M, Ierodiakonou I, Waitzkin H, Benos A. Economic crisis, restrictive policies, and the population’s health and health care: the Greek case. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(6):973–979. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang SS, Gunnell D, Stern JA, Lu TH, Cheng AT. Was the economic crisis 1997–1998 responsible for rising suicide rates in East/Southeast Asia? Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(7):1322–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reeves A, Stuckler D, McKee M, Gunnell D, Chang SS, Basu S. Increase in state suicide rates in the USA during economic recession. Lancet. 2012;380(9856):1813–1814. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61910-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. America’s property crisis: the hammer drops. The Economist. October 4, 2007. Available at: http://www.economist.com/node/9905451. Accessed April 15, 2013.

- 11.Current Housing Reports, Series H150/09, American Housing Survey for the United States. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2009. p. 20401. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Massachusetts woman commits suicide before home foreclosure. 2008. Available at: http://www.foxnews.com/story/0, 2933, 389822,00.html. Accessed December 3, 2012.

- 13.Little L. California man commits suicide before foreclosure. 2012. Available at: http://abcnews.go.com/Business/calif-man-commits-suicide-foreclosure-wells-fargo/story?id=16405456. Accessed August 23, 2013.

- 14. Facing eviction, a man killed himself while a deputy stood at door. 2009. Colorado Springs Gazette. Available at: http://www.denverpost.com/commented/ci_11706069. Accessed April 15, 2013.

- 15.McLaughlin KA, Nandi A, Keyes KM et al. Home foreclosure and risk of psychiatric morbidity during the recent financial crisis. Psychol Med. 2012;42(7):1441–1448. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pollack CE, Lynch J. Health status of people undergoing foreclosure in the Philadelphia region. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(10):1833–1839. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alley DE, Lloyd J, Pagán JA, Pollack CE, Shardell M, Cannuscio C. Mortgage delinquency and changes in access to health resources and depressive symptoms in a nationally representative cohort of Americans older than 50 years. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(12):2293–2298. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Currie J, Tekin E. Is there a link between foreclosure and health? 2011. NBER Working Paper w17310. Available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1918640. Accessed July 15, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Shen X, Millet L. Homicides Related to Intimate Partner Violence in Oregon: A Seven Year Review. Portland, OR: Oregon Department of Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart L, Kabore J, Brown S. Intimate Partner Violence-Related Deaths in Oklahoma. Oklahoma City, OK: Oklahoma State Department of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Violence and Injury Prevention Program. Domestic violence fatalities in Utah 2003–2008. 2010. Available at: http://health.utah.gov/vipp/pdf/DomesticViolence/2003-2008%20Report.pdf. Accessed January 17, 2012.

- 22.Klevens J, Leeb R. Child maltreatment fatalities in children under 5: findings from the National Violence Death Reporting System. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34(4):262–266. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Gang homicides—five US cities, 2003–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(3):46–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan MS, McFarland B, Huguet N. Characteristics of adult male and female firearm suicide decedents: findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Inj Prev. 2009;15(5):322–327. doi: 10.1136/ip.2008.021162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Logan J, Hill HA, Lynberg Black M et al. Characteristics of perpetrators in homicide-followed-by-suicide incidents: National Violent Death Reporting System—17 US states, 2003–2005. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(9):1056–1064. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karch DL, Logan J, McDaniel D, Parks S, Patel N. Surveillance for violent deaths—National Violent Death Reporting System, 16 states, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;61(SS-6):1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Statistic Brain Research Institute. Home foreclosure statistics. 2012. Available at: http://www.statisticbrain.com/home-foreclosure-statistics. Accessed March 6, 2013.

- 28.Bennett GG, Scharoun-Lee M, Tucker-Seeley R. Will the public’s health fall victim to the home foreclosure epidemic? PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000087. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Stressful life events and major depression: risk period, long-term contextual threat, and diagnostic specificity. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186(11):661–669. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199811000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nettleton S, Burrows R. Families coping with the experience of mortgage repossession in the “new landscape of precariousness.”. Community Work Fam. 2001;4:253–272. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benassi VA, Sweeney PD, Dufour CL. Is there a relation between locus of control orientation and depression? J Abnorm Psychol. 1988;97(3):357–367. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Immergluck D, Smith G. The impact of single-family mortgage foreclosures on neighborhood crime. Housing Stud. 2006;21(6):851–866. [Google Scholar]

- 33.2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pollack CE, Pelizzari P, Alley D, Lynch J. Health concerns at mortgage counseling sessions: results from a nationwide survey. Foreclosure Response Issue Brief. 2011 . Available at: http://www.foreclosure-response.org/assets/foreclosure-response/Pollack_HealthConcerns.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2013. [Google Scholar]