Abstract

Objective

The aim of the present study was to characterize sickle cell disease retinopathy in children and teenagers from Bahia, the state in northeastern Brazil with the highest incidence and prevalence of sickle cell disease.

Methods

A group of 51 sickle cell disease patients (36 hemoglobin SS and 15 hemoglobin SC) with ages ranging from 4 to 18 years was studied. Ophthalmological examinations were performed in all patients. Moreover, a fluorescein angiography was also performed in over 10-year-old patients.

Results

The most common ocular lesions were vascular tortuosity, which was found in nine (25%) hemoglobin SS patients, and black sunburst, in three (20%) hemoglobin SC patients. Peripheral arterial closure was observed in five (13.9%) hemoglobin SS patients and in three (13.3%) hemoglobin SC patients. Arteriovenous anastomoses were present in six (16.5%) hemoglobin SS patients and six (37.5%) hemoglobin SC patients. Neovascularization was not identified in any of the patients.

Conclusions

This study supports the use of early ophthalmological examinations in young sickle cell disease patients to prevent the progression of retinopathy to severe disease and further blindness.

Keywords: Sickle cell anemia, Disease SC, Retinopathy

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is characterized by the presence of the hemoglobin S (Hb S) variant due to a single nucleotide change (GAG → GTG) in the β-globin gene (HBB) that replaces a glutamic acid with a valine at the sixth position of the β-globin chain. The hemoglobin C (Hb C) variant is characterized by a point mutation at the sixth position of the HBB gene, wherein a lysine replaces a glutamic acid at the sixth position of the β-globin chain.1

Hb S has a high overall frequency worldwide; in Brazil its distribution is heterogeneous. In northeastern Brazil, in particular in Bahia, the population has a tri-racial mixture of Europeans (mostly Portuguese), Africans and indigenous Brazilians.2 The frequency of Hb S in the state of Bahia is the highest in Brazil, varying from 4.5 to 14.7% in different population groups.3

Sickle cell disease is characterized by a variety of clinical abnormalities that are frequently linked to hemolytic anemia and the vaso-occlusive processes often responsible for the pain and other clinical features described by patients, including retinopathy.1,4

Methods

The present study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Board of the Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ), and informed consent was obtained from the guardians of participants in accordance with ethical principles and in accord with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and its revisions. Ophthalmologic examinations were carried out and peripheral blood samples were collected only after signed informed consent has been obtained.

This cross-sectional study involved a group of 51 SCD patients (36 Hb SS and 15 Hb SC) from the state of Bahia in northeastern Brazil and was carried out during the period of January 2010 to December 2012.

Patients were randomly selected among those attending the Hematology Outpatient Clinic at the Fundação de Hematologia e Hemoterapia da Bahia (HEMOBA), a referral center for SCD patients who are seen in routine visits. Patients were then sent to the Instituto Brasileiro de Oftalmologia e Prevenção da Cegueira (IBOPC) for an eye examination, including fundus biomicroscopy and indirect binocular ophthalmoscopy in all patients and fluorescein angiography in over 10-year-old patients. The following findings were observed in the fundoscopic examination: vascular tortuosity, black sunburst pattern, salmon patches and iridescent spots. The pathologic classification of fundoscopic alterations as proliferative was based on Goldberg's five stage grouping: stage I – peripheral arteriolar occlusions; stage II – peripheral arteriovenous anastomoses; stage III – preretinal neovascularization; stage IV – vitreous hemorrhage and stage V – retinal detachment.

Patients with proliferative retinopathy were stratified by age and were classified as severe when displaying stages III–V. The hemoglobin pattern was confirmed in the Hematology, Genetic and Computacional Biology Laboratory of FIOCRUZ and the Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA) using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC – Variant I/BIO-RAD, CA, USA).

SPSS version 18.0 and GraphPad version 5.0 were used to store and analyze the data. Pearson's Chi-squared or Fisher's exact tests were used to compare the two groups of SCD patients as necessary. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 51 SCD patients were enrolled in this study: 36 (70.6%) with sickle cell anemia (SCA) or Hb SS and 15 (29.4%) with Hb SC disease. Overall, the mean age of the patients was 11.76 ± 3.69 years. The Hb SS group had a mean age of 11.39 ± 3.76 years, and the Hb SC group had a mean age of 13.29 ± 2.8 years. Overall 23 (45%) SCD patients were female and 28 (55%) were male. In the Hb SS group, 19 patients (52.78%) were male and 17 (47.22%) were female, and in the Hb SC group, nine (60%) were male and six (40%) were female.

Visual acuity was 20/20 or 20/25 for the best eyes of all patients, corresponding to 90% of the total number of cases.

Age-related ocular lesions, both non-proliferative and proliferative (Goldberg) (Figs. 1–4), were very frequent in both groups of patients (Hb SS and Hb SC). Table 1 shows the distribution of ocular lesions across the two age groups. The Hb SS group had more ocular changes in the age range 0–9 years old. In the Hb SC group of patients, ocular changes were more frequent in the age range 10–18 years old.

Figure 1.

Tortuous vessels in an 11-year-old female with hemoglobin SS.

Figure 2.

Black sunburst. Hyperpigmented lesions observed in the retinal periphery of an 18-year-old female with hemoglobin SC.

Figure 3.

Salmon patches in a 13-year-old male with hemoglobin SC.

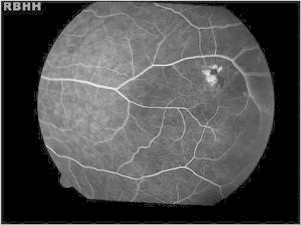

Figure 4.

Peripheral arteriolar occlusions and arteriovenous anastomoses in a 14-year-old male with hemoglobin SC.

Table 1.

The distribution of retinal vessel occlusion lesions across two age groups of sickle cell disease patients.

| Total (n = 51) |

Hemoglobin SC (n = 15) |

Hemoglobin SS (n = 36) |

p-valuea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 0–9 | 4 | 36.4 | – | – | 4 | 20.0 | 0.02 |

| 10–18 | 7 | 17.5 | 9 | 22.2 | 16 | 80.0 | 0.008 |

Fisher's exact test

Vascular tortuosity and black sunbursts were the most common fundoscopic ocular lesions found in both SCD groups (Hb SS and Hb SC). Table 2 shows that vascular tortuosity lesions were most frequent in the Hb SS group. However, black sunburst lesions were more frequent in the Hb SC group. Iridescent spots were found in both groups of SCD patients.

Table 2.

Fundoscopic ocular non-proliferative lesions in both sickle cell disease groups.

| Hemoglobin SS (n = 36) |

Hemoglobin SC (n = 15) |

Total (n = 51) |

p-valuea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Vascular tortuosity | 9 | 25.0 | 1 | 6.7 | 10 | 19.6 | 0.95 |

| Black sunburst | 2 | 5.6 | 3 | 20.0 | 5 | 9.8 | |

| Salmon patches | – | – | 1 | 6.7 | 1 | 2.0 | |

| Angioid streaks | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Disk sign | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Iridescent spots | 3 | 8.3 | 1 | 6.7 | 4 | 7.8 | |

| Total | 14 | 38.9 | 6 | 40 | 20 | 39.3 | |

Chi-square.

Table 3 shows the distribution of proliferative ocular lesions across Goldberg stages I–V in the Hb SS and Hb SC patient groups. There were patients in both groups with proliferative ocular lesions in Goldberg stages I and II; however, the Hb SS group had more proliferative ocular lesions in the first stage than the Hb SC group; this increased with age in the Hb SC group. There were no cases of proliferative ocular lesions at stages III–V in either of the groups of SCD patients.

Table 3.

The distribution of proliferative ocular lesions for Goldberg stages I–V in the hemoglobin SS and hemoglobin SC groups.

| Hemoglobin SS |

Hemoglobin SC |

p-value | Total |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Normal | 25 | 69.4 | 6 | 40.0 | 0.09a | 31 | 60.8 |

| Ocular Lesions (Goldberg) | 11 | 30.6 | 9 | 60.0 | 20 | 39.2 | |

| Stage I | 5 | 13.9 | 3 | 13.3 | 08 | 15.7 | |

| Stage II | 6 | 16.7 | 6 | 37.5 | 12 | 23.5 | |

Yates corrected Chi-square test.

Discussion

Several ocular changes were observed in the two SCD patient groups; however, no change in visual acuity was found, as has previously been reported.5–10

Fundoscopic lesions, such as vascular tortuosity and black sunbursts, were the most frequent changes, in accordance with previous Brazilian reports.7–11 The overall frequency of vascular tortuosity was most frequently in SCA patients, as previously described.10–12 The black sunburst lesion was observed in both groups, although its frequency in Hb SC patients was much lower than that described in previously published studies.10–13 Salmon patch lesions were present only in the Hb SC group; however, their occurrence has been reported in both groups albeit more frequent in the Hb SC group.10–13 Iridescent spots were found in both groups, but they were less common than previously reported, which is probably because these alterations are at sites of salmon patch resolution and appear less in younger patients.14,15

This study indicates that retinal vascular disease occurs in both Hb SS and Hb SC patients and proliferative retinopathies (Goldberg stages) begin early in the Hb SS group and are more common in both groups with older ages.11,12

Proliferative retinopathy (stages III–V) was not observed in our study, probably as the patients were very young rather than old.16–20 Fox et al.19 studied Jamaican patients and observed that ocular proliferative lesions in both genotypes increase with age.

Conclusions

The ocular lesions described herein may help to define standardized protocols involving the clinical and ophthalmologic follow-up of Hb SS and Hb SC patients especially for younger patients. Multiple ocular complications exist for SCD patients, and continuous assessment is required to detect lesions early enough for effective prophylactic therapy.

It is necessary to recommend that SCD patients receive periodic ophthalmological examinations at early ages to prevent progression of the disease and early blindness, establish a more effective treatment, and assure a better quality of care for patients’ eyes.

Funding

This study was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) (311888/2013-5) (M.S.G.), the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado da Bahia (FAPESB) SECTI/SESAB (3626/2013, 1431040053063, and 9073/2007), the Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia do Sangue (INCT do Sangue-CNPq), and Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ)/Ministério de Saúde do Brasil; project code: MDTP 1.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ohene-Frempong K., Steinberg M.H. Clinical aspects of sickle cell anemia in adults and children. In: Steinberg M.H., Forget B.G., Higgs D.R., Nagel R.L., editors. Disorders of hemoglobin: genetics, phatophysiology and clinical management. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2001. pp. 611–670. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azevêdo E.S., Fortuna C.M., Silva K.M., Sousa M.G., Machado M.A., Lima A.M. Spread and diversity of human populations in Bahia, Brazil. Hum Biol. 1982;54(2):329–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azevêdo E.S., Alves A.F., Da Silva M.C., Souza M.G., Muniz Dias Lima A.M., Azevedo W.C. Distribution of abnormal hemoglobins and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase variants in 1200 school children of Bahia, Brazil. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1980;53(4):509–512. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330530407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vilela R.Q., Bandeira D.M., Silva M.A. Alterações oculares nas doenças falciformes. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2007;29(3):285–287. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg M.F. Classification and pathogenesis of proliferative sickle cell retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1971;71(3):649–665. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(71)90429-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Condon P.I., Serjeant G.R. Ocular findings in hemoglobin SC disease in Jamaica. Am J Ophthalmol. 1972;74(5):921–931. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(72)91213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonanomi M.T., Cunha S.L., de Araújo J.T. Funduscopic alterations in SS and SC hemoglobinopathies. Study of a Brazilian population. Ophthalmologica. 1988;197(1):26–33. doi: 10.1159/000309913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Popma S.E. Ocular manifestation of sickle hemoglobinopathies. Clin Eye Vis Care. 1996;8(2):111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akinsola F.B., Kehinde M.O. Ocular findings in sickle cell disease patients in Lagos. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2004;11(3):203–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia C.A., Fernandes M.Z., Uchôa U.B., Cavalcante B.M., Uchôa R.A. Achados fundoscópicos em crianças portadoras de anemia falciforme no Estado do Rio Grande do Norte. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2002;65(6):615–618. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cury D., Boa Sorte N., Lyra I.M., Zanette A.D., Castro-Lima H., Galvão-Castro B. Ocular lesions in Sickle Cell disease patients from Bahia, Brazil. Rev Bras Oftalmol. 2010;69(4):259–263. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talbot J.F., Bird A.C., Serjeant G.R., Hayes R.J. Sickle cell retinopathy in young children in Jamaica. Br J Ophthalmol. 1982;66:149–154. doi: 10.1136/bjo.66.3.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moriarty B.J., Acheson R.W., Condon P.I., Serjeant G.R. Patterns of visual loss in untreated sickle cell retinopathy. Eye (Lond) 1988;2(Pt. 3):330–335. doi: 10.1038/eye.1988.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Welch R.B., Goldberg M.F. Sickle-cell hemoglobin and its relation to fundus abnormality. Arch Ophthalmol. 1966;75(3):353–362. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1966.00970050355008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg M.F. Retinal vaso-occlusion in sickling hemoglobinopathies. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1976;12(3):475–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldbaum M.H., Jampol L.M., Goldberg M.F. The disc sign in sickling hemoglobinopathies. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96(9):1597–1600. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1978.03910060231008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gagliano D.A., Goldberg M.F. The Evolution of salmon-patch hemorrhages in sickle cell retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107(12):1814–1815. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020896034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliveira F.V., Aihara T., Cançado R.D. Alteraçöes fundoscópicas nas hemoglobinopatias SS e SC. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 1996;59(3):234–238. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moraes Junior H.V., Araújo P.C., Brasil O.F., Oliveira M.V., Cerqueira V., Turchetti R. Achados oculares em doença. Rev Bras Oftalmol. 2004;63(5/6):299–302. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox P.D., Dunn D.T., Morris J.S., Serjeant G.R. Risk factors for proliferative sickle retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1990;74(3):172–176. doi: 10.1136/bjo.74.3.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]